Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 37

February 24, 2017

Online Class on Prayer for Lent

Registration is now open for my online class on prayer for Lent!

Registration is now open for my online class on prayer for Lent!  It’s called “Focus on Prayer.” Together we’ll learn about and practice three classic ways of praying that will help bring new focus and renewal to your prayer life.

It’s called “Focus on Prayer.” Together we’ll learn about and practice three classic ways of praying that will help bring new focus and renewal to your prayer life.

I hope you’ll join us!

No matter what background you come from something here’s bound to be new to you: we will be looking at ways of praying with deep roots in the Reformed tradition of Protestantism, in Eastern Orthodoxy, and in Roman Catholicism.

I taught this class on my own website for the 1st time last year — though I’ve taught this material many times at the seminary level, and in churches, and at conferences and retreats.

We had a lot of fun together.

At least one member of the class described it as “life-changing.”

Each week we’ll do four things together:

I’ll introduce a way of praying with a short video lecture.

I’ll point you toward a more complete exploration of that way of praying in my book Kneeling with Giants Learning to Pray with History’s Best Teachers.

You’ll practice that way of praying for about 15 minutes a day.

You have the opportunity to find support and accountability, and share and learn from others in a private discussion forum.

It’s a way to become far more focused in your prayer life.

It’s a way to make Lent time of growth in Christ that Lent was made to be.

It’s a way to learn more about the spiritual lives of Christians in other traditions.

It might just be away to find a way of praying that really fits who God made you to be.

You can find out more through the link in the menu at the top of the page.

And if you’re willing to share about this class with others in your church or circle of friends just use the social media buttons below, or send them this link: http://bit.ly/LentenPrayerClass

I hope to see you in class!

Gary

The post Online Class on Prayer for Lent appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 20, 2017

Treasure in Earthen Vessels (The Writer’s Inner Life)

(This is the fourth post in a series on writing an icon in the Orthodox Christian tradition. To start at the beginning, click here.)

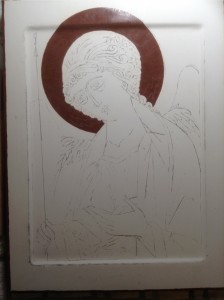

Once the lines are drawn and inscribed on the gesso board, I’m itching to get my brushes and add some paint.

Not so fast. My teachers had a very specific step-by-step process for me to follow. Paint was still a few steps away.

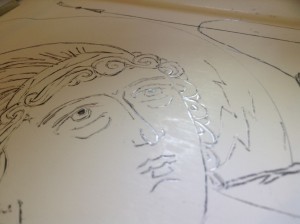

First comes the halo. The seemingly endless process of the halo.

Maybe it is good that it takes time, this halo, this reminder of God’s glory shining through the saint’s life. In real life it takes a long while to become the kind of person who bears that light. Me, I’m still waiting.

The Circle

First a perfect circle has to be inscribed around the head of the saint. The drawing had a tiny “x” on it to mark the place to put one needle-foot of a compass as well as marks to show the radius.

First a perfect circle has to be inscribed around the head of the saint. The drawing had a tiny “x” on it to mark the place to put one needle-foot of a compass as well as marks to show the radius.

(My teacher pointed out that using a compass is a good reminder to humility. We all need some help to draw a perfect circle.)

I fitted the outer foot of the compass with a second needle point, and carefully inscribed the circle, shoulder to shoulder.

The Clay

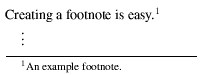

Inside the circle, from the inscribed circumference to the hair and shoulders, I then had to apply “bole,” a mixture of red clay and glue made from rabbit hide.

Inside the circle, from the inscribed circumference to the hair and shoulders, I then had to apply “bole,” a mixture of red clay and glue made from rabbit hide.

And some distilled water. And just a bit of honey. An ancient recipe I’m sure.

But finally I was painting something: not paint but red clay, in a thick layer.

My teacher pointed out the significance of red clay. In the Hebrew of Genesis, the first human being, “Adam,” was made of clay, “Adama.” Red clay — the same root as “Edom.”

Previously trying to read an icon I saw with my eyes that the halo was gold. The saint shines with God’s light.

True enough.

Writing an icon, I now know with my hands that underneath the gold is the earthy red clay of human nature. Ahh… even truer. Saints are really human, created, earthy. Same as all of us underneath.

Once the clay is dry, sanded smooth, and burnished to a gloss with an agate tool or polished stone, it will be ready for gold.

Once the clay is dry, sanded smooth, and burnished to a gloss with an agate tool or polished stone, it will be ready for gold.

Now that I think about it, that process too is full of significance for me.

The humanity of the saint starts out with red clay, just like anyone else. But then in the midst of life there is a process of transformation — sanctification, becoming like Jesus.

And the things that make me more like Jesus are often rather painful. Like sandpaper on the clay, the rough places of my life must be made plain. By friction and abrasion, not unlike that done by a burnishing stone, my life must become capable of bearing the light. Painful, but profitable.

The Gold

Then gold, real pure gold, gets applied to the clay.

Then gold, real pure gold, gets applied to the clay.

You buy gold leaf in pricy little books, each sheet a couple inches square and about an atom thick.

Sneeze and it’s smashed to bits.

My teacher laid a single sheet of gold on a bit of wax paper. It stuck very slightly to the wax paper, making it easier to get into position.

I totally forgot about the wax paper when I was working on my icon of Archangel Gabriel. Oops. My gold went on in whispey fragments.

If you take up iconography, here’s my advice to you: Don’t forget the wax paper.

But the really cool thing, the most amazing part of the process, is the application of that gold.

You have your gold ready.

You put your face close to the clay.

You breath, slowly, on the clay.

Your breath warms the surface of the clay and glue mixture, making it tacky.

You lay the gold down and press upon the wax paper.

And there it is. Shining like the glory of God from the gesso board.

Think again about Genesis. God made Adam from that red clay. The clay was lifeless — until God breathed into it.

Treasure in Earthen Vessels

So now, when I see the gold halo on an icon, I remember. Red clay, breathed on by God, with the result of life — glorious life, a gift from God.

I hope to be reminded of this as I bring my own life to God in prayer. There is an earthen vessel, always. May it shine like gold — what the apostle called treasure in earthen vessels.

And I hope to be reminded of this as I bring ideas to life in my more familiar types of writing. As the words come through my hands they are very much like clay. May God draw near and help them shine by the Spirit’s own breath, and do his work in the world.

————

Lent is coming! What a great time to focus on your prayer life.

Click the button to get info on my online prayer class for Lent…

The post Treasure in Earthen Vessels (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 16, 2017

Do You Cite Your Sources in Sermons? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

CC by Jovan.Andj1996-SA 4.0

CC by Jovan.Andj1996-SA 4.0Dear ______:

Well I suppose you are right on both counts: I didn’t quite answer your question, and I didn’t explain my most interesting point very well. Sorry. I’ll give it another go.

You asked

Just how much do pastors depend other people’s commentaries in their sermon development? How much is reading or quoting others and how much is new effort or synthesis?

I think the answer depends very much on the preacher — and the quality of the preacher’s preaching.

A preacher who lacks skill or confidence will often depend almost entirely on commentaries.

A confident preacher will be more likely to present his or her own synthesis.

That confidence, by the way, may be based on skill or it may be pure hubris.

And it isn’t just commentaries people depend on. There are websites that provide pre-fab sermons for a fee, and there are thousands of published sermons in books, on blogs, and on YouTube.

Failing to Cite Your Sources in Sermons

Famous preachers with books of published sermons have been known to visit churches and hear their own sermons preached to them.

The handshake at the door after the service? Awkward.

One time (I’m not making this up) I heard a seminarian preach a chapel sermon centering on a witty story about her son.

The next Sunday (the very next) I was in another city, and the pastor of the church I was visiting preached a sermon centering on the exact same witty story about his son.

It was such a distinctive story. It seemed there were only two possible explanations.

The seminarian and the pastor, living hundreds of miles away from each other, had managed to have a secret affair. They produced a child, who had then had the experience behind the witty story.

Both the seminarian and the pastor were plagiarizing the same published source of witty sermon stories.

But I digress.

The more common problem (I think and hope) is pastors who use commentaries excessively, making their sermons a patchwork of quotations, with or without acknowledgment.

Better Ways to Cite Your Sources in Sermons

It is perfectly legit to quote someone in a sermon. But you need to cite your sources in a sermon — though in a different way than you would in a paper.

I’d suggest you follow a couple of simple rules:

Rule 1. Mention Your Sources

Whenever you quote someone in your sermon, especially a published source, note the fact verbally:

As John Calvin once said…

or whatever. No need for formal footnotes. That would be deadly.

To quote (or substantially paraphrase) without acknowledging the source is simply dishonest. The words or ideas are not your own. Don’t pretend they are.

Rule 2. Digest Your Sources First

Make sure anything you quote in the sermon is fully digested and fully integrated into your own sermon.

That means your sermon should not go from quotation to quotation without providing connections and explanations in between. And your words and ideas should be substantially greater in volume than those you quote.

Rule 2(b). Especially the Funny Sources

This second rule has another application as well: especially when the quotation is a funny story or a moving story, look very closely to make sure it actually supports the point you discerned from your biblical text.

A good story has gravity like a black hole. Many many preachers get sucked into a funny or moving story, and just can’t let it go. They preach the great story even though the story has nothing to do with the point Scripture is making.

Gotta go for now. I’ll explain the point you found interesting, about listening to God in the sermon, another time.

Blessings,

Gary

The post Do You Cite Your Sources in Sermons? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 14, 2017

Is Faith Simple? Should it Be? (Heidelberg Catechism Q60)

CC by Tallent Show-SA 2.0

CC by Tallent Show-SA 2.0Question 60 is one of the unsung heroes of the Heidelberg Catechism (you know — that’s the summary of biblical Christianity from a Reformed perspective that I’ve been blogging on since it’s 450th anniversary in 2013).

Maybe it’s better to say it’s one of the hinge points. You might argue it’s the culmination of the 1st half of the catechism.

The Catechism spent a long time on faith. Now, it tells us, the point of faith is that by faith we are made righteous.

All this creates a problem though. It sounds too simple. Is faith simple?

Here it is in full:

60 Q. How are you righteous before God?

A. Only by true faith in Jesus Christ.

Even though

my conscience accuses me

of having grievously sinned against all God’s commandments,

of never having kept any of them,

and of still being inclined toward all evil,

nevertheless,

without any merit of my own,

out of sheer grace,

God grants and credits to me

the perfect satisfaction, righteousness, and holiness of Christ,

as if I had never sinned nor been a sinner,

and as if I had been

as perfectly obedient

as Christ was obedient for me.

All I need to do is accept this gift with a believing heart.

If you were to read the first half of the catechism in order you would find this answer pointing back to key assertions to make its point about how righteousness comes from faith.

All of that is hidden in the “even though,” and “nevertheless.”

Even Though

It starts by saying our conscience accuses us and our nature keeps us aimed toward evil — that’s a summary of the first big section of the catechism about our misery and brokenness due to sin (questions 3-11).

Nevertheless

Then it goes on to summarize God’s reconciling mission in Christ as described both in the section on Christ’s person (questions 12-18) and in the exposition of the Creed about the events of Christ’s work (questions 29-52).

So since this question largely points back to things dealt with long before, I want to draw out two other points:

one that illustrates the Catechism’s pattern of Christian and biblical thinking in a useful way,

and one that might be troubling — at least until he think about some of the points earlier in the catechism that are assumed.

As If

The Catechism’s pattern of thinking is hinted at in the little phrases “as if”

as if I had never sinned…

as if I had been as perfectly obedient as Christ.

There is an imaginative quality to this. It is more than a simple rational argument.

You see a hypothetical quality to the Catechism pondering how God considers us to be righteous. It requires us to be flexible in our thinking.

We imagine God imagining us and our situation. Is God being imaginative, not to say playful, in the very serious matter of solving our greatest problem?

No: Better to say that when God imagines something, that becomes the way it really is.

This “as if” is a pattern of thinking that will come up again when we see how the catechism explains the sacraments.

All I Need to Do

Every time I read this question though, I am troubled. The closing sentence seems to trivialize faith in the closing sentence:

all I need to do is accept this gift with a believing heart.

I get the same troubling feeling as when Christians present salvation on simplistic tracts:

Just say “the sinner’s prayer”.

Just ask Jesus into your heart.

Just say you are sorry for your sins.

It’s all you need to do .

Is the Catechism being so simplistic? All I need to do is be a little more believing. All I need to do is take what is held out in God’s hand.

Being a Christian really is about faith — but if you read the rest of the Catechism, you know that real faith is a major undertaking.

True faith, questions 19-25 tell us, is about an utterly bedrock life change, where we cease to be at enmity with God and begin to trust God’s goodness and love in Christ.

That kind of trust permeates every aspect of our being. True faith changes everything. And it takes a lifetime to live it.

————

Lent is coming! What a great time to focus on your prayer life.

Click the button to get info on my online prayer class for Lent…

The post Is Faith Simple? Should it Be? (Heidelberg Catechism Q60) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 13, 2017

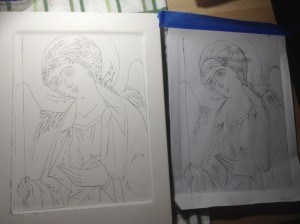

The Lines of the Image (The Writer’s Inner Life)

(This post is third in a series on writing an icon in the Orthodox Christian tradition. To start at the beginning, click here.)

(This post is third in a series on writing an icon in the Orthodox Christian tradition. To start at the beginning, click here.)

If I were more advanced, I would be putting my own drawing on the board. I would work on a classical model, thinking hard about issues of geometry, style, and symbolism as well as drawing a human figure skillfully.

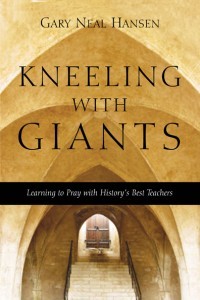

But I’m a rank beginner. Thankfully the teachers of the workshop I took provided us with line drawings for our first two icons: Archangels Michael and Gabriel.

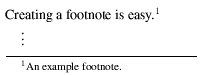

I start out with a photocopy and a sheet of carbon paper.

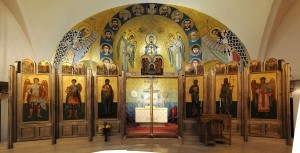

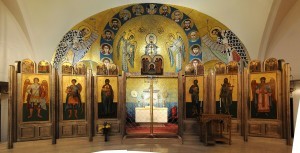

At the workshop we did Michael, whom you’ll see in Orthodox Churches on the door at the far left side of the iconostasis, the wall-like structure with its row of saints in front of the altar. At the far right door of the same wall you’ll find Gabriel.

Gabriel and Michael are basically mirror images of each other, with some differences in the colors of their clothes. They both are slightly turned toward the center of the wall, where you see Jesus.

Types vs. Portraits

All the saints on the wall turn toward Jesus, actually. They gesture toward him, framing him, the source of salvation.

Their lives reflected Jesus. That’s what made them saints.

Even if I had done my own drawing for the icon I’m writing now, it would look similar to other icons of the Archangel Gabriel. It would probably be recognizably my own, but the point is that it needs to be recognizably Gabriel. Each person rendered in an icon has their own set of recognizable features.

Those features, in turn, are displayed in a very specific traditional style.

An icon is not supposed to portray the person like a photograph, or even as a classic painted portrait would.

And an icon does not attempt to convey the personal emotions of the person portrayed.

The icon is more conveying something like what older biblical interpreters would call the “type” of the saint.

In biblical interpretation “typology” is where one visible thing (the type) points to something else (the antitype) in a kind of divine revelation.

Most commonly Old Testament events are read as types hinting of the coming of Jesus in the flesh.

Yet death exercised dominion from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sins were not like the transgression of Adam, who is a type of the one who was to come. (Romans 5:14 NRSV)

Or earthly things can be types revealing the heavenly, as the earthly tabernacle or the temple were sketches or shadows of the throne room of God in heaven.

They offer worship in a sanctuary that is a sketch and shadow of the heavenly one; for Moses, when he was about to erect the tent, was warned, ‘See that you make everything according to the pattern that was shown you on the mountain.’ (Hebrews 8:5 NRSV)

Maybe it is easier to make the point with reference to something in icons other than people.

Take mountains. In every classical icon, the mountains look quite similar. And they don’t look like any mountains you will ever see on any earthly horizon.

Take mountains. In every classical icon, the mountains look quite similar. And they don’t look like any mountains you will ever see on any earthly horizon.

They are “types” of mountains. They communicate the idea of mountains, or maybe the “mountain-ness” of mountains.

What you see on the board isn’t ultimately about the person of the saint. It points to the reality of a life that revealed Christ.

And it is those lines, the Christ-revealing lines, that need to be brought out and remembered.

Transferring the Lines

In any case, I taped the drawing to the board along the top. Using a pencil or a stylus I followed each line, transferring the image to the surface of the board.

In any case, I taped the drawing to the board along the top. Using a pencil or a stylus I followed each line, transferring the image to the surface of the board.

But before the first bit of paint could be added, something more had to be done: Each line had to be cut into the gesso surface with the sharpened steel point of a stylus.

Left unengraved, the lines would be lost as I applied the six or more layers of paint. The figure would drift and lose its proper shape.

But with the lines engraved with a stylus, I’ll always be able to find them.

Because of the engraving, the image will always be there, no matter how I mess up in my painting.

The Lines of the Image

My teacher drew our attention to the symbolism here: We are created in the image of God. The lines are always there, no matter how we mess up.

There is an iconographic quality to every human you encounter. Life adds layer upon layer to this original image. You and I both know how thoroughly that image can be obscured in us. Some theologians have even argued that it is completely destroyed.

But the lines are still there. Like an icon in the hand of an unskilled artist, the image may be obscured and hidden. We may look a mess. But no matter how messy, the lines are there, and God is the skilled artist who can restore us.

… seeing that you have stripped off the old self with its practices and have clothed yourselves with the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge according to the image of its creator. (Colossians 3:9-10 NRSV)

Writing an icon is about becoming aware of the process of my own redemption, an act of creation that teaches how the Creator works to restore me.

————

Lent is coming! What a great time to focus on your prayer life.

Click the button to get info on my online prayer class for Lent…

The post The Lines of the Image (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 6, 2017

Gesso on a Wooden Board (The Writer’s Inner Life)

(Second in a series on writing an icon in the Orthodox Christian tradition. Click here to start at the beginning.)

(Second in a series on writing an icon in the Orthodox Christian tradition. Click here to start at the beginning.)

It all starts with a white gesso board.

No. That’s not right. The board is not actually white with gesso, ready to receive lines and paint, until the fourth step of the process.

If I were to start with the official steps listed on the handout

#1 is the preparing the wood of the board itself

#2 is sealing it with glue made from animal hide and a linen cloth

#3 is applying nine layers of gesso, followed by careful wet and dry sanding

Thankfully, in the workshop I took we started with boards already prepared for us.

(You can buy them on the internet. They are not cheap. If you’ve ever wondered at the price of a handwritten icon, note that the materials may have cost $100 if the artist started with a prepared board, and uses real gold leaf and natural pigments. And the process had about 18 steps after the board was ready, each of which probably took an hour or more.)

The Prayer

But I digress. Even if I had started with a bare pine plank, the process would actually begin with prayer. My teacher gave us a two page prayer litany to say each day before beginning work on our icons together. The heart of it was this:

Guide the hands of Thine unworthy creatures in this present task, to the venerable portrayal of Thine Image for the glory and adornment of Thy Church. Direct our hearts and souls, and grant unto us noetic illumination. Grant unto us, and those that venerate these holy icons in honor whom they represent, restoration from sin. Through the proper veneration of the icons instruct us with Thy good counsel, and deliver us from evil.

The whole process is about prayer, drawing close to God in intimate, transforming communion. That is true for the painter. It is also true for the one who makes use of the finished icon.

The Gesso Board

Back in that first step the board was shaved down in the center, leaving a higher frame to surround the figures. This surely has a protective function, as icons are moved about in the church and that frame gets touched or kissed by the faithful.

But as with all things in the process, whether by intention or by later meditation, this rim is laden with symbolic meaning.

As the saint is a kind of “container” of the Holy Spirit, the place where God has chosen to be revealed, so the rim of the icon is a kind of “ark,” for carrying the icon’s revelation on the lower level of the board.

And as my teacher said, it physically reminds us that we have to dig down below the surface to find the spiritual reality of things.

The Light

And then you unwrap the prepared board. The gesso is white, smooth, hard, bright.

It seems like the equivalent of a canvas for a painter in oils.

But it turns out you don’t aim to cover up the white of the gesso. The gleaming white will be like light shining up through layer upon translucent layer of egg tempera paint. It will, in a sense, be visible in the finished icon.

In competent hands this technique can convey a complex sense of depth — and light. My teachers were insistent that the whole process is not about laying down color and shadow, but about the layering up of different kinds of light.

And it all begins with the work of God, our creator, whose light shines underneath all creation and especially through human beings, created in God’s own image. No matter how smudgy and ill-crafted the image becomes in our fallen hands, God’s light lays underneath it and shines through.

The Writing

Now I ponder this in relation to my other kinds of writing. Can they too be so prayerful?

As I write about aspects of human experience, Christian life, theological reflection, what will happen if I remember that, underneath it all, God’s own light is shining?

The blank page is much like the gessoed board. I tend to only think about my own scrawling creation on that page. But perhaps the page itself shines with the light of God.

————

Lent is coming! What a great time to focus on your prayer life.

Click the button to get info on my online prayer class for Lent…

The post Gesso on a Wooden Board (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 2, 2017

Commentaries in Preaching? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

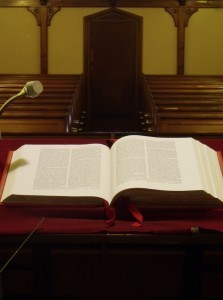

CC BY Jonathan Billinger SA 2.0

CC BY Jonathan Billinger SA 2.0Dear ______:

Glad to hear that the preaching class is moving from frightening to exciting. Preaching should probably always be both.

And you are surely right when you suggest that preaching for a preaching class is very different from preaching every single Sunday in a church.

Commentaries in preaching

That’s true in quite a lot of ways, but for today I’ll stick to the question you asked:

Just how much do pastors depend other people’s commentaries in their sermon development? How much is reading or quoting others and how much is new effort or synthesis?

My answer: Use commentaries just enough to help you past the hard bits. Then preach from your own encounter with God in the text for the sake of the congregation.

Commentary as help

Commentaries are a very useful kind of theological writing. The pastor must jump head first into a challenging text, and be ready to present on it in public. The turnaround time from first examination to sermon is often less than a week.

Standing up in the pulpit and saying

Well that text is a real stumper. I couldn’t make heads or tails of it.

does not impress. Or help.

Whether the text is confusing or from an unfamiliar part of Scripture (and nobody is equally comfortable with every text) a commentary gives you a jump start. It also helps you see problems you might glide right by in your favorite passages.

A commentary points out the hard words, confusing contexts, seeming contradictions. It tries to make sense of it all, usually basing its clarity on years of scholarly inquiry.

So when you need a tour guide to the strange new worlds of Scripture, commentaries can be crucial.

Commentary as problem

On the other hand, commentaries can be used as a substitute for your own direct exploration of the passage.

My wife likes to tease me about a hike we took long ago. We had a map with GPS coordinates and I was excited to have a new GPS. We inched across the countryside.

Finally I said,

According to the GPS coordinates there should be a bridge somewhere along here.

She said

Look up.

We were standing in front of the bridge.

You are taking people on a journey (we hope) through the text to the rich and life-giving word of God. Keep your eyes on the commentaries and you miss all the actual scenery.

Plus you risk sounding like you are trying to impress people with all the books you have read. If someone you read says something perfectly for your purposes, by all means quote it. (And name the source.)

But if your sermon is full of quotations it will be a burden and an irritation to your listeners.

Remember your calling

The calling of a preacher is to stand in the middle:

On the one side is God, calling out to the people.

On the other side is the congregation, needing to hear a word from God.

In the middle is you, the preacher, and the Bible where God has always chosen to speak.

If you are too timid to dive into the text, or too unskilled at listening to God there, then you might end up standing in front of your congregation and reading commentaries.

In effect the commentary-laden sermon is like me, looking at the GPS instead of the terrain:

I don’t know what God is saying to us through this text, but here are a bunch of things smart people wrote about it.

The congregation called you, and showed up to listen to you. They can read commentaries for themselves.

They know you can’t perfectly discern God’s personal message every week. But they are counting on you to wrestle with the text and listen hard to God. They need you to speak to them out of your own wrestling.

The textbook assigned for your class probably recommends a process for you to study the passage you are preaching on. It may include commentaries in that process, but commentaries probably won’t be the whole process.

Here’s what I would recommend:

Wrestle until you have questions you can’t answer.

Then look at commentaries.

Then go back to wrestling.

Your sermon will only be interesting or useful if it flows from your own encounter with God in the text.

Blessings,

Gary

————

If you enjoyed the post, I hope you’ll share it using the buttons below…

The post Commentaries in Preaching? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

January 30, 2017

Writing an Icon (The Writer’s Inner Life)

CC by Joe Mabel-SA 2.0

CC by Joe Mabel-SA 2.0Recently I told the readers of my newsletter that I’m exploring writing of another kind: I’m “writing” an icon as taught in the Orthodox tradition.

I asked them to let me know if they would be interested in reading about the process.

A number of people said “Yes.”

Precisely the same number of people clicked “Unsubscribe.” (Oh well.)

But still, nobody said “No.”

So, as we say at Presbytery meetings, “The ‘ayes’ have it.”

Especially because the “Yes” votes included both people whom I know well and whom I do not know personally at all, plus one who helped teach me iconography.

Plus, the “Yes” votes were enthusiastic. (I can’t tell how enthusiastically people were unsubscribing.)

The posts on iconography will be part of my Monday “inner life of the writer” series.

Telling you why is a good way to start the series.

Painting an icon is writing.

If you ever enter an Orthodox church one of the first things you will notice is the icons — paintings of Jesus and of Mary, of other Bible people and Bible stories, and of post-biblical saints.

You will see them in the entry way.

You will see a long row of them on the screen between the congregation and the altar table.

You’ll see a couple on stands in front of that screen.

You will see them, maybe many of them, on the walls.

You’ll probably even see them on the ceiling.

You might be tempted to think that these are decorations. The Orthodox do refer to them that way at times. But really they are windows and, in a Protestant sense, pulpits.

As “windows” (a very traditional description) the faithful look not at icons but through them to the presence of God who is revealed in the people and scenes they portray.

As “pulpits” (my own word) the gospel is preached in them.

It is in this role as pulpits that icons use a language.

It is a very specific language, made up of

line

color

and symbol.

And those who know the language quickly grasp the gospel message.

We Reformed Protestants don’t usually know that language. We emphasize only the spoken word. For us the gospel is proclaimed by the voice and received by the ear.

But in our culture we are increasingly aware that different people learn differently.

Some do well with hearing a lecture.

Some need to learn through activities for their bodies.

And some learn better by seeing with their eyes.

Orthodox icons are, at the very least, a language for the visual learner to grasp and respond to the good news of Christ.

The very word “iconography” is as much about language as it is about painting. The “-graphy” at the end of the word means “writing.”

So iconography is just expanding my writing repertoire, kind of like I would if I were learning to write in French or Chinese.

Writing an icon is part of my inner life.

My first foray into iconography was a week-long workshop offered by the Prosopon School. My teachers were two master iconographers who immigrated from Russia years ago, Vladislav Andrejev (the founder of the school) and his son Dmitri.

St Nicholas and the Nine Gold Coins on Amazon

St Nicholas and the Nine Gold Coins on Amazon  St George & the Dragon on Amazon

St George & the Dragon on Amazon

(If you want to see some of their work, check out the school’s website above. If you’d like to own a wee bit of it and see it in detail, check out these awesome children’s books on two of the most popular Orthodox saints, illustrated by Vladislav in iconographic style.)

The teachers of the Prosopon School are steeped in the ancient traditional methods of iconography. More importantly to me, they are steeped in the spiritual teaching that lies behind the methods.

They emphasized from the beginning that artistic skill was not a prerequisite. That’s good: I like to draw but make no claims for my abilities.

In fact, fully half of our time together was spent listening to Vladislav lecture about the spiritual theology of Orthodoxy as embodied in iconography. Every element, every step, every technique, is rich with meaning and symbol.

And to write an icon according to the tradition, you need to know that theology and live into it as a spiritual practice.

Contemplating the symbolic meanings of the steps became a key aspect of the practice. It is all about prayer, and the journey toward restoration of the image of God in us.

I’m really happy to be exploring this kind of writing. I hope you’ll share the journey with me. And I hope you’ll share your thoughts along the way in the comments or by email.

————

This post contains affiliate links.

The post Writing an Icon (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

January 27, 2017

Recommended Reading: Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom

St Basil, St. John Chrysostom, St. Gregory Nazianzus

St Basil, St. John Chrysostom, St. Gregory NazianzusThis week the Orthodox cycle of saints included not one but two of my favorites: Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom. Both were Archbishops of Constantinople back in one of my favorite centuries: the fourth.

The fourth century was the time of the biggest arguments about the biggest issues, and so became the time of the first global Councils to define Christian doctrine.

And times of big conflict sometimes bring out the best in people. John and Gregory, in particular, had good minds to begin with. Then they had well formed lives of Christian discipleship. When they found themselves in prominent positions, they poured out their lives to understand and teach the faith and help people live it.

These guys so shaped theology, worship, and Christian living that they are still remembered as two of the “Three Hierarchs,” along with St. Basil of Caesarea. Icons frequently portray them as a group, though John was born after Basil’s death. The grouping is about influence.

John and Gregory compiled the two primary forms of the Divine Liturgy still used today.

They wrote works about the life of a Christian minister that are better than anything that has followed.

They taught. And they preached.

Gregory’s teaching (especially in his “Five Theological Orations”) was so important that he became one of only three Orthodox saints to be nicknamed “The Theologian.”

And his writing is beautiful. I once met a grad student who set out to master Patristic Greek–which is much tougher than the biblical Koine– just so he could read the Five Theological Orations in their original language.

John’s preaching was so filled with insightful biblical exegesis, and so effective in helping people live the biblical faith, that he got nicknamed “The Golden Mouth,” (that is, “Chrysostom”). Later his sermons were published as Bible commentaries.

And he had serious courage: He sheltered religious refugees condemned by the emperor. He preached against the bad behavior of the Empress when she showed up for worship.

Preaching about problematic government leaders is relatively easy when they aren’t around. And they usually are not around. Chrysostom’s insistence on preaching faithful discipleship led to his being exiled. He was forced farther and farther away until he died.

Recommended Reading

If I could, I would convince you to read some of their works. They aren’t easy at the first go. Some are only available in old and rather wooden translations. Even when translated well, readers of modern English are not used to the long sentences, the cadences, and the kinds of arguments in these books.

But stick with it. Read them twice. Once you get used to it they reward your labors.

And you can do it for free! Most of what exists by these guys is readily available online in translation on the Christian Classics Etherial Library. Here’s Gregory. And here’s John.

You can even download and print a nice pdf. Underline it. Highlight it. Take notes.

Go for it. Pick something fun. If you want recommendations, send me an email.

And once you do pick one and read it, let me know what you think. I’d love to hear from you!

————

If you find the idea of reading great theological texts appealing but know that you need some company and accountability, I have a great idea for you.

I’m working out a plan for an online reading group. I’ll choose great texts and provide introductions and a reading schedule for members. For those who are game to share the journey, there will be a private discussion forum.

If you want me to keep you posted, click the button below.

The post Recommended Reading: Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

January 26, 2017

Your First Sermon (Letters to a Young Pastor)

CC by Charles Clegg SA-2.0

CC by Charles Clegg SA-2.0Dear ______:

Well I have to say your letter brought me joy: I know being in your first preaching class makes you nervous, but I think it is just great.

Whether you become “a preacher” full time or not, Christians are given good news to share with the world. Preaching class is a lab to learn to do that.

I hope your first sermon is a great experience for you and those who listen to you.

Your first sermon

Once, at a conference for ministers where I was giving a keynote, one of the other speakers told the story of a seminarian in just your situation. He went to his pastor for some advice.

Pastor, I have to preach my first sermon. What should I preach about?

asked the seminarian.

The pastor, an old southern gentleman, leaned back and thought.

Well, you should preach about Jesus,

he said, slowly.

And, you should preach about fifteen minutes.

A pretty good pastor joke, and pretty solid advice as well.

Preach about Jesus

The advice to preach about Jesus is an excellent starting point. Having listened to a great many student sermons in seminary chapel services I can tell you that from experience.

Setting out to preach about Jesus will help you avoid two common sermon pitfalls:

1. You are not there to preach about yourself.

Many new preachers focus their sermons on the story of their own faith. There are two problems with this.

First, you are not the gospel. If you preach about yourself, you are giving the people far less than they need.

Second, you only have one faith story. Some get started by preaching their own story, and finding it well received, stick to it. They preach it again.

But when the same congregation comes back the next week they actually need a new sermon.

Some stick to their own story for a very long time. The same conversion, or the same recovery from tragedy, or whatever it may be, comes up again and again.

It just isn’t enough.

2. You are not there to preach about the congregation

Some take the other tack, and turn their attention to the people in the pews. The 19th century revivalist Charles Finney did this with great success. He talked about people and prayed about them by name from the pulpit, making them squirm in guilt until they repented.

I think it has probably failed everywhere since then. Think of it as committing yourself to short-term ministry.

It can be as straightforward as the fellow I once heard once who stepped into the pulpit and said

This won’t be so much a ‘sermon’ as a ‘manifesto’.

Ouch.

When you are pastor of a congregation you will, of course, in various ways, need to preach about the community’s life and mission.

But you aren’t there to make the congregation feel bad.

And you probably shouldn’t be trying to convert them to Christian faith. If they showed up in your preaching class or your congregation they probably have that one down already.

And just as you are not the gospel, the congregation is not the gospel. Preaching about them is not enough.

You need to preach about Jesus. He is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. He is the one who has the living water. He is the one who is God in the flesh, the very substance of our salvation.

Only Jesus will meet their need.

Preach about fifteen minutes

There is a book on preaching from twenty years ago called The Four Pages of the Sermon.

I have not read it, though I’ve heard it recommended. What I recommend to you is the concept in the title:

Write your first sermon out in full (your first many sermons, actually) even if you plan to preach from memory. Type it out in a 12 point Times font, double-spaced with one inch margins.

It should be about four pages long. Maybe five or six, but no more.

For someone new to preaching, this can be a really helpful guide.

If you only have a page or two, you will be sitting down again just as the congregation figures out what you are talking about.

If you have seven or eight pages they will be checking their phones for texts long before you’ve made your point.

Fifteen minutes talking about Jesus Christ is an excellent goal for a new preacher.

Fifteen minutes hearing and thinking about Jesus will be an excellent faith-building time for your hearers.

Preach about the text

Of course if you are going to say anything useful about Jesus you’ll need to be preaching about a text of Scripture. More on that another time…

Blessings,

Gary

————

Lent is coming! What a great time to focus on your prayer life.

Click the button to get info on my online prayer class for Lent…

————

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Your First Sermon (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.