Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 42

August 26, 2016

The Paradoxical Presence of Christ (Heidelberg Catechism Q47)

Nik Wallenda, cc by Jennifer Huber-SA2.0

Nik Wallenda, cc by Jennifer Huber-SA2.0A couple weeks ago I was reflecting on a much-neglected biblical teaching: the ascension of Christ. We may neglect it because there is a conundrum in the ascension: the puzzling, if not an outright paradoxical presence of Christ.

Ascension vs. Presence

The last scenes of Jesus’ earthly ministry are emphatic about two completely opposite things:

Jesus promised to be with us always, even to the end of the age. (Matt. 28:20)

Jesus left, ascending into heaven. (Mark 16:19, Luke 24:51, and Acts 1:9)

Most of us, most of the time, don’t fret about that too much. Both sides seem true.

We have some kind of sense that Christ is active within us or around us. That matches up with the promise in Matthew.

We don’t actually see Jesus in person. That matches up with the Ascension.

If there is a paradox between those two points, we are pretty much over it.

Until we aren’t.

If you think about the Ascension, the absence of Christ may start to bug you. If Jesus went up to heaven, isn’t he just … gone?

Are we fooling ourselves when we think about Jesus being with us

in our hearts

in the Lord’s Supper

or active in the world?

The writers of the Heidelberg Catechism (the much-loved Reformed summary of biblical theology I’ve been blogging about, off and on, since it’s 500th anniversary in 2013) comes right out and asks the question:

47 Q. But isn’t Christ with us until the end of the world

as he promised us?

A. Christ is true human and true God.

In his human nature Christ is not now on earth;

but in his divinity,

majesty,

grace,

and Spirit

he is never absent from us.

It was an important point for Reformation-era Protestants, actually.

Lutheran vs. Reformed

At the Marburg Colloquy of 1520, when all the Protestants tried to come together, their differences came down to how they thought about the Lord’s Supper — and the Ascension.

Martin Luther looked to the words of Jesus at the Last Supper, “This IS my body,” and said that it was a promise : Jesus is really, physically present in the Eucharist.

Ulrich Zwingli and others on the Reformed side looked at the Ascension and said Jesus’ body is in heaven. We can’t have him physically present, even at the Eucharist. We should listen instead to Jesus’ command : “Do this in REMEMBRANCE of me.”

The Heidelberg Catechism came more than a generation later, in 1563. The writers were walking a tightrope:

They were trying to establish the Reformed understanding of the faith.

They were in a territory legally obliged to follow Lutheran theology.

They didn’t want to fall all the way in either direction. Or better to say, like any tightrope walker they had to keep equal weight on both sides to stay steady.

So they looked at the incarnation in a way that was familiar to readers of John Calvin, and a bit controversial among Lutherans — though its roots go all the way back to the Greek theology of the ancient Alexandrian tradition.

The Incarnation of the Logos

Now hang in there with me…

In the early centuries, Greek-speaking theologians were delighted to see that John 1 said that “In the beginning was the Word” or “Logos.” The Logos, said John, actually was God, and through the Logos all creation came into being.

A reader of Greek philosophy would know that the LOGos was that thing that made creation orderly, rational — LOGigcal.

The Logos wasn’t just a simple word that was spoken. The Logos is what made all of creation make sense. The Logos kept it all hanging together.

Without the Logos, the whole universe would tumble into chaos and nothingness.

So what about when the Logos became human in Jesus? Jesus was the incarnation of the Logos. Does that mean that outside Jesus there was no Logos?

Ah… there’s the actual paradox. A much bigger paradox than the Ascension.

Jesus, walking around in the flesh, was truly, and fully the Logos.

But all the while, the Logos was maintaining the entire universe.

In other words, the Logos was

not constrained

not contained

not limited

to the measure of Jesus’ body.

The Logos continued to order the whole of the universe outside Jesus even when the Logos became incarnate as Jesus.

The paradoxical presence of Christ

The Ascension sort of reverses the original paradox:

Christ’s human flesh ascended into heaven.

Meanwhile, the divine Logos, Jesus, remains present with us — and will remain with us even to the end of the age.

Do you find Jesus’ ascension and presence with us paradoxical? Helpful? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

The post The Paradoxical Presence of Christ (Heidelberg Catechism Q47) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 22, 2016

Accidie — The Noontime Demon (The Writer’s Inner Life)

cc by Tony Bowden SA 2.0

cc by Tony Bowden SA 2.0I’m working on making my working life happy and productive without having to punch a clock or meet institutional deadlines.

So my advisors at the moment are the Desert Fathers and Mothers, Christians who moved out to the fourth century Egyptian desert for an isolated life of prayer.

Sometimes they hit it straight out of the park, not just for the spiritual life of monks but for an ordinary Christian writer.

They knew how to organize their inner lives to achieve goals few others understood.

But the clues are sometimes hidden in the unfamiliar vocabulary. Take, for instance the saying I was writing about a couple weeks ago. Here’s how it starts:

When the holy Abba Anthony lived in the desert he was beset by accidie…

This one would be perfectly clear except for this one very unfamiliar word.

Accidie? What’s Accidie?

Actually it is too bad the word accidie has fallen out of use. It is the classic name for a problem that afflicts everyone who tries to do focused creative work.

Try writing a dissertation. You spend the morning working hard. Come the afternoon the project that once filled you with passion seems worthless. Your ability to complete it? Hopeless.

Writing a novel? Painting a landscape? Come mid-day the problems feel weighty. Anything would be better than this. I mean, hey, it’s just my life’s most important work.

I suspect that most afternoons in the Egyptian desert somebody said

Hey! Wouldn’t this be a great time to clean the bathroom?

Distractibility. Exhaustion. Depression. Doing what needs to be done just seems impossible.

I had accidie when I was a university student. There was this early afternoon Economics class. I simply could not keep my eyes open. The class was pretty interesting. But about 1:20, with a morning of work behind me and a tummy full of lunch, I was sunk.

On every page of notes, half-written words ended in rat tails. My eyes closed and the pen skidded across the page.

So I didn’t do that well in Econ.

Accidie Personified: Resistance

Prominent novelist and uberblogger Steven Pressfield calls it “Resistance” — which is basically accidie personified, working to keep you from completing the work that lies closest to your heart.

Pressfield is not the first to think of accidie as a personal and evil force. Sometimes it has been called “the noontime demon.” That’s when it most likes to pounce.

You look back on your work day and see the distractions were pure temptations: The work was what you were called to and passionate about.

One of the most famous of the Desert Fathers, Evagrius of Pontus, talked about it this way, and he had a helpful prescription to deal with it. Here are two short sayings from another of Benedicta Ward’s translations:

4. Evagrius said, ‘If your attention falters, pray. As it is written, pray in fear and trembling (cf. Phil. 2:12), earnestly and watchfully. We ought to pray like that, especially because our unseen and wicked enemies are trying to hinder us forcefully.’

5. He also said, ‘When a distracting thought comes into your head, do not cast around here and there about it in your prayer, but simply repent and so you will sharpen your sword against your assailant.’ (Unceasing Prayer, p. 131)

Evagrius, like Pressfield, personifies the problem. He places the blame on demonic forces.

Evagrius’ two-point plan for the Noontime Demon

Demonic or not, Evagrius has wise recommendations for anyone doing creative work.

First, pray. When you find yourself distracted from your heart’s work, turn your attention back to God. For the Desert Fathers, of course, prayer was their main work. But the approach is helpful to the rest of us. Don’t punish yourself. Don’t give in. Focus on God who brings refreshment and healing.

Second, repent. Gently put your mind back on the next task in your calling. “Repent” doesn’t mean “beat yourself up.” The word means to change your mind.

When the shopping list or the bill that needs paying or the argument with your friend creeps into your mind, kindly bring it back.

If you find your mind on the wrong thing, turn your mind to the right thing — a thousand times if need be.

Evagrius’ two approaches together make a great approach to accidie.

Gently turn your attention toward God, who called you to write this essay, this novel, this sermon.

Then hand in hand with God, turn back to the work itself — a thousand times if need be.

Turn back to your calling. Turn back to the path and take the next step.

A step in the work to which God calls you is a step toward life.

Keep walking, even on a stony path. The direction of your calling is toward God.

————

Ever face accidie? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

————

This post contains affiliate links.

The post Accidie — The Noontime Demon (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 18, 2016

Shouldn’t This Be Easy? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

cc by Roger Norton 2.0

cc by Roger Norton 2.0Dear ______:

Thanks for your note. You are definitely right: seeking a mountaintop experience is by no means the only off-target assumption people bring to seminary.

And the assumptions that you bring make a big difference on the experience you have.

Anyway, the conversations you mention point to another assumption that can keep people from thriving.

As you put it,

A whole lot of people here seem to think seminary is too much work.

I’m glad this one isn’t troubling you personally, but maybe if you think it through you can give a helpful nudge to some of your fellow students.

Of course I don’t know your friends personally, but I can say I’ve known quite a few seminarians who have every appearance of asking

If God really called me to this, shouldn’t this be easy?

That thought may never get said out loud. It may never even get thought out so clearly. But a lot of people begin to doubt their call when they face a few hard assignments or get that first round of grades.

Is God’s Call Usually Easy?

There is a theological question to ponder here. Is God’s call in your life supposed to be easy?

To take just one biblical example, consider the Apostle Paul. Here he’s making a mocking comparison of his experience with other Apostles. His ministry was filled

with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings, and often near death.

Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one.

Three times I was beaten with rods.

Once I received a stoning.

Three times I was shipwrecked;

for a night and a day I was adrift at sea;

on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters;

in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked.

And, besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. (2 Cor. 11:23-28)

Easy-peasy, lemon squeezy — not.

You could make the same case from the life stories of Abraham, Moses, David, Elijah, Jeremiah, and others.

Well what about later times? Isn’t it all blessings now that we are after the times of the Bible?

Think of St. Athanasius, the theologian who shaped our understanding of the Trinity. He spent his adult life in and out of exile, fighting for orthodox teaching.

Think of John Calvin, the Reformation theologian who so shaped Protestantism. His entire adult life was spent in exile. Though he found himself best suited to the quiet life of a scholar, he was constantly thrust into local and international conflict.

Think of the countless martyrs who have been tortured and murdered for their faith in Christ.

O yes, I know, but they didn’t have my Systematic Theology prof! She’s brutal!

Could a good seminary really be easy?

Personally I don’t think a good seminary education can be easy, at least for the vast majority of people.

Each of us is good at some things, skating through some subjects. Most of us also struggle in some things.

For example, if your undergraduate degree is in Spanish or German, you have some language learning skills. You’ll probably find your language work in Greek and Hebrew comes easier to you than to many.

Those excellent language skills may not help you at all in theology — while your friend with the philosophy degree finds it a breeze.

When you look around the curriculum of the typical seminary you don’t just find a variety of subjects. You find find half a dozen or more classes that require completely different skill sets.

Your professor is not there to give you an affirming grade for being such a nice person, or even for trying so hard.

He or she wants you to take on the homework tasks that will help you grow in the skills of

a historian

a biblical scholar

a linguist

a theologian

a counselor

and a public speaker.

Hardly anyone finds all of those things easy.

You’ll be better off in the long run if you try to learn all you can about each course’s skill set as well as the specific content of the subject.

And you’ll have more joy if you focus on learning skills and content rather than on your report card. No one else is ever going to care about your report card.

Blessings,

Gary

The post Shouldn’t This Be Easy? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

Shouldn’t This Be Easy? (Letters to a Young Pastor

cc by Roger Norton 2.0

cc by Roger Norton 2.0Dear ______:

Thanks for your note. You are definitely right: seeking a mountaintop experience is by no means the only off-target assumptions people bring to seminary.

And the assumptions that you bring make a big difference on the experience you have.

Anyway, the conversations you mention point to another assumption that can keep people from thriving.

As you put it,

A whole lot of people here seem to think seminary is too much work.

I’m glad this one isn’t troubling you personally, but maybe if you think it through you can give a helpful nudge to some of your fellow students.

Of course I don’t know your friends personally, but I can say I’ve known quite a few seminarians who have every appearance of asking

If God really called me to this, shouldn’t this be easy?

That thought may never get said out loud. It may never even get thought out so clearly. But a lot of people begin to doubt their call when they face a few hard assignments or get that first round of grades.

Is God’s Call Usually Easy?

There is a theological question to ponder here. Is God’s call in your life supposed to be easy?

To take just one biblical example, consider the Apostle Paul. Here he’s making a mocking comparison of his experience with other Apostles. His ministry was filled

with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings, and often near death.

Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one.

Three times I was beaten with rods.

Once I received a stoning.

Three times I was shipwrecked;

for a night and a day I was adrift at sea;

on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters;

in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked.

And, besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. (2 Cor. 11:23-28)

Easy-peasy, lemon squeezy — not.

You could make the same case from the life stories of Abraham, Moses, David, Elijah, Jeremiah, and others.

Well what about later times? Isn’t it all blessings now that we are after the times of the Bible?

Think of St. Athanasius, the theologian who shaped our understanding of the Trinity. He spent his adult life in and out of exile, fighting for orthodox teaching.

Think of John Calvin, the Reformation theologian who so shaped Protestantism. His entire adult life was spent in exile. Though he found himself best suited to the quiet life of a scholar, he was constantly thrust into local and international conflict.

Think of the countless martyrs who have been tortured and murdered for their faith in Christ.

O yes, I know, but they didn’t have my Systematic Theology prof! She’s brutal!

Could a good seminary really be easy?

Personally I don’t think a good seminary education can be easy, at least for the vast majority of people.

Each of us is good at some things, skating through some subjects. Most of us also struggle in some things.

For example, if your undergraduate degree is in Spanish or German, you have some language learning skills. You’ll probably find your language work in Greek and Hebrew comes easier to you than to many.

Those excellent language skills may not help you at all in theology — while your friend with the philosophy degree finds it a breeze.

When you look around the curriculum of the typical seminary you don’t just find a variety of subjects. You find find half a dozen or more classes that require completely different skill sets.

Your professor is not there to give you an affirming grade for being such a nice person, or even for trying so hard.

He or she wants you to take on the homework tasks that will help you grow in the skills of

a historian

a biblical scholar

a linguist

a theologian

a counselor

and a public speaker.

Hardly anyone finds all of those things easy.

You’ll be better off in the long run if you try to learn all you can about each course’s skill set as well as the specific content of the subject.

And you’ll have more joy if you focus on learning skills and content rather than on your report card. No one else is ever going to care about your report card.

Blessings,

Gary

The post Shouldn’t This Be Easy? (Letters to a Young Pastor appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 15, 2016

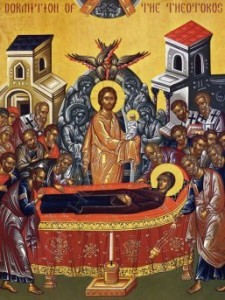

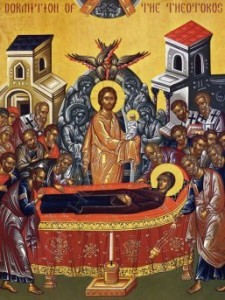

Looking into the Gap: The Dormition of our Most Holy Lady the Theotokos

If I were to pick one item of teaching or practice that best marks the distinction between Protestants and the more ancient traditions of Christianity it would have to be Jesus’ mom.

If I were to pick one item of teaching or practice that best marks the distinction between Protestants and the more ancient traditions of Christianity it would have to be Jesus’ mom.

She’s huge to both Orthodox and Catholic Christians. Protestants? Not so much.

Not too long ago I heard a Protestant sermon in which the preacher was emphasizing important women in the Bible. Each of a dozen or so got a short remembrance. And that’s good: we do tend to only emphasize the contributions of the boys.

But guess who was not even mentioned in a sermon on the most important women of the Bible?

Mary: the woman on whom salvation history hinges.

I mean Mary was chosen by God to bear God’s only begotten Son, truly human and truly God, the savior of the world.

This is a very big deal. If Mary had said “No thanks” to Gabriel, we would all be sunk.

We are so concerned by Catholic excesses about Mary that we often won’t mention her at all — even when recounting important women of the Bible.

You’d think we didn’t actually like her.

So August 15 just a hot summer day for Protestant Christianity. It is one of the most important feasts for Orthodox and Catholic Christians.

What’s your Assumption about the “Dormition”?

Orthodox call August 15 “The Dormition of our Most Holy Lady the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary.” Catholics call it “The Assumption of the Virgin Mary into Heaven.”

You can piece together the Orthodox tradition’s version of Mary’s story from the hymns and prayers from Matins, or Morning Prayer, for the feast.

(You can get a fuller exposition of the tradition from the OCA website, though if you happen to be a historian you will at least smile at the use of sources.)

It goes something like this:

Mary was much beloved of the Apostles because Christ was born of her.

From Mary came Jesus’ humanity, while from his Father came Jesus’ divinity.

Mary died.

Rather than decaying, her body emitted a sweet scent.

Mary’s soul was miraculously seen ascending to Jesus.

Mary’s body was buried in a tomb.

When the tomb was opened, her body was gone — ascended into heaven.

The thing is, we Protestants really should be fine with most of this. Only points 4, 5 and 7 should surprise anybody.

It is our post-Enlightenment assumptions about history that leaves us troubled by sweet fragrances from saints’ bodies, visions of heaven, and miraculous ascensions.

We might be okay with these things when the Bible mentions the same things — with Lazarus, Stephen, and Elijah for instance. But when they have just been passed down by faithful Christians we raise an eyebrow.

Personally I love Mary. I think she has an amazing place in salvation history.

I am not surprised in the least that ancient Christians sang her praise. It makes perfect sense that Christians would be drawn to the tenderness of the woman who nurtured Jesus himself.

If we want to be like Jesus, we should love what Jesus loves.

That probably starts with his mom, right?

The post Looking into the Gap: The Dormition of our Most Holy Lady the Theotokos appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 12, 2016

Should You Look for a Mountaintop Experience? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

Dear ______:

Dear ______:

Thanks for writing. Glad you found the distinction between Protestant and Non-Protestant seminaries useful.

Seminary as new car showroom?

Yes, your car analogy works pretty well:

Protestant seminaries are built on the chassis of an academic program, with spiritual features and option packages.

Catholic and Orthodox seminaries are built on a monastic chassis, modified to satisfy the academic equivalent of the National Highway Traffic Safety Agency.

No matter what analogy you use, you’ll get better mileage (snicker) out of your program, and out of your Christian life in general, if you steer clear (get it?) of one common assumption people bring to seminary:

Avoid the idea that seminary is going to be a spiritual mountaintop experience.

Seminary as mountaintop experience?

Many people find themselves called to Christian ministry, or at least to seminary education, when they have had a spiritual mountaintop experience:

an adult conversion

a summer in mission work

a “Walk to Emmaus” or “Cursillo” retreat

These experiences put people in contact with God in new and life-changing ways. They bring a big wake-up call, an opportunity to decide on new paths.

The mistake is thinking that three years of seminary are going to be three years on top of that mountain.

Seek God, not experiences

The best writers on the spiritual life will tell you you should not be seeking mountaintop experiences.

You should be seeking God. Any experience in the world of your feelings and senses is less than God.

Sometimes the presence of God gives you big feelings. Sometimes nada.

And if you do have a mountaintop experience, eventually you have to come back down and do life. To integrate real change, you live life in light of what you learned on the mountain.

So write about it in your journal. Keep pictures of where you were when you met God so powerfully. Meet with others who had the same kind of experience. But you can’t recreate it or maintain it.

Even Moses, who met God face to face on a literal mountaintop, only stayed up there for 40 days. A human being can only bear so much of the unfiltered presence of God.

Seminary as place of growth

God willing, seminary will have some moments of profound change, and the powerful emotions of mountaintop experiences. But that really isn’t the aim — and it certainly isn’t the measure of whether seminary is worthwhile.

If you were in a more monastic seminary, transformation would come with living the life of community in the rhythm of prayer and worship.

Since you are in a more academic seminary, transformation happens differently, in a more Protestant way, as you study, and learn, and integrate the subject matter.

Actually both things happen in both kinds of seminary: both community and class are crucial.

Either way, you basically have to live the real life, taking responsibility for your spiritual growth, and taking advantage of all the grinding mundane challenging work that your seminary provides for your growth.

Keep driving,

Gary

If you enjoyed the post, please share it on your favorite social media site!

The post Should You Look for a Mountaintop Experience? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 9, 2016

Why Proclaim that Christ Ascended? (Heidelberg Catechism Q46)

Ascension Icon cc by Ted 2.0

Ascension Icon cc by Ted 2.0One traditional Christian teaching that many today simply ignore is Christ’s “Ascension.” Why proclaim that Christ ascended into heaven?

One answer is that it is simply biblical. You find it at the end of both Mark and Luke, but Acts 1 is the version that sticks in our collective memory. The risen Christ has just given the Acts version of the Great Commission:

When he had said this, as they were watching, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight.” (Acts 1:9, NRSV)

Jerusalem, we have lift-off.

But if post-Enlightenment Christians have a hard time thinking about Jesus walking on water, the ascension doesn’t even enter their consciousness.

But the story communicates a number of important things, some pretty basic and some more subtle.

Why proclaim Christ Ascended?

On the basic side, Christ’s ascension to heaven affirms his bodily resurrection while giving a clear reason that we don’t bump into him on the street.

The Heidelberg Catechism (that classic exposition of biblical theology beloved of the Reformed Tradition and on which I’ve neglected to blog for far too long) explores a number of the subtler issues. It devotes four questions to this little line of the Apostles’ Creed, one of which I discussed long ago.

Here’s the first question in the sequence:

46 Q. What do you mean by saying, “He ascended to heaven”?

A. That Christ,

while his disciples watched,

was taken up from the earth into heaven

and remains there on our behalf

until he comes again

to judge the living and the dead.

I don’t want to wrestle very hard with any of this today. I think it is better to point out the theological and poetic connections of this short statement with four aspects of our faith.

First is the affirmation of the biblical scenes, the scriptural drama in which the doctrine is rooted. Christ ascended “while his disciples watched” in Mark 16:19, Luke 24:51, and Acts 1:9.

Second is the connection to the rest of the Creed. Jesus will return “to judge the living and the dead.” (The Catechism will get to this in Question 52.)

Third I hear an allusion to the liturgy of the Eucharist in the phrase “until he comes again.” This points directly to the Words of Institution (1 Cor. 11:26). Also, in the West at least, we summarize the great “mystery of faith” saying “Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.”

Fourth is a quiet emphasis on a central theme of the Heidelberg Catechism itself. Christ is ascended to heaven “on our behalf.”

Over and over the Catechism emphasizes how the whole of the gospel, and all of theology, is to help us. It is useful.

It isn’t just an intellectual exercise. The whole thing is to make our lives better. It is for us.

Christ is for us.

Christ died for us.

Christ’s body and blood are given for us.

Christ died, rose, ascended, reigns and will return for us.

This is also a biblical allusion of course. But that’s the point. The Catechism is teaching us biblical theology.

Theology as poetry, not as argument

These are poetic connections, intentional echoes of language across a variety of important texts.

That is different from logical arguments. Often Christians give in to our culture’s pseudo-scientific mindset, thinking we need rational proofs.

Instead what Scripture, and the best of theology, often give us is food for our souls in the form of poetry, story, and song — the things that make for a life of depth and meaning.

The post Why Proclaim that Christ Ascended? (Heidelberg Catechism Q46) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 8, 2016

Find Your Rhythm (The Writer’s Inner Life)

Having big chunks of time to work on a creative project is a gift. It also brings problems. How do you keep at work with no looming deadlines, no timecard to punch, and no boss?

Having big chunks of time to work on a creative project is a gift. It also brings problems. How do you keep at work with no looming deadlines, no timecard to punch, and no boss?

As I move fully into writing, speaking, and other independent work, I’m facing those challenges daily. Of course I’m facing them my my own way: in conversation with wise souls from the Christian past.

Right now I’m finding wise counsel from the Desert Fathers and Mothers. Back in the fourth century they chose the solitude of the Egyptian desert for the ultimate unsupervised challenge: the pursuit of God.

They had a vague goal, no deadline, and a lot of time on their hands. Perfect.

Solitude: the gift and the problem.

I keep coming back to one saying from St. Anthony the Great — he was sort of the Father of the Desert Fathers. Here’s how it goes (from Benedicta Ward’s wonderful translation of the Alphabetical Collection):

When the holy Abba Anthony lived in the desert he was beset by accidie, and attacked by many sinful thoughts. He said to God,

“Lord, I want to be saved but these thoughts do not leave me alone; what shall I do in my affliction? How can I be saved?”

A short while afterwards, when he got up to go out, Anthony saw a man like himself

sitting at his work,

getting up from his work to pray,

then sitting down and plaiting a rope,

then getting up again to pray.

It was an angel of the Lord sent to correct and reassure him. He heard the angel saying to him, “Do this and you will be saved.”

At these words, Anthony was filled with joy and courage. He did this, and he was saved.

I like this one so much that it isn’t the first time I’ve blogged about it. But now I’m reading it against a different background: I’m now working independently as a writer, speaker, and consultant.

Soon there would be thousands of monks in the desert but Anthony was ahead of the curve. He didn’t have role models to look back on. He had nobody nearby to go chat with.

(That wouldn’t always be the case. We have whole collections of their sayings because they kept hanging out with each other and asking for advice.)

He was alone. There was nothing to do but what he came to do, right? No Facebook. No Minecraft. Just Anthony himself.

Turns out being with yourself is enough to distract you from your calling.

Two problems, one solution

Anthony struggled with two problems: “accidie” and “sinful thoughts.”

Accidie is that lethargy that hits midday when anything, even a gameshow, can distract you from the project you are truly passionate about.

Sinful thoughts come in many shapes and colors: A classic list is pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, anger, and sloth.

More on all these troubles another time. Let’s just say Anthony isn’t the only one troubled by them: They can all bring my writing to a standstill.

The cool thing about this story, though, is the solution: Anthony learns the power of finding his rhythm.

He can’t expect to pray intensely every waking hour. For one thing he needs to do some work to earn money for food.

The angel shows him to divide his time into shifts of praying and labor.

Find your rhythm

As a writer I need exactly what Anthony got in his vision: a rhythm.

There are lots of ways to establish that rhythm.

Many swear by the “pomodoro” technique of 25 minutes of work followed by a 5 minute break.

Some intersperse a walk, a coffee, or another reward.

Some take turns between the creative parts of their work and the more mundane.

But everybody needs a rhythm.

I’m trying to let what I know of the monastic life structure my days.

In a monastery they have eight daily periods of prayer, alternating with other kinds of work. It may sound like too much but in my monastic retreats, projects that normally would take months got done in a week or two.

So I’m using an app of the monastic prayer cycle to structure my time. My goal is to have a life like Anthony saw in his vision.

Do a shift of focused writing.

Turn to a time of prayer.

Do another shift of writing.

Turn again to prayer.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

Having a structure and a rhythm keeps me from stumbling over all the obstacles I bring along with me.

——

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Find Your Rhythm (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 4, 2016

What Kind of Seminary Is This? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

Oxford — Public Domain

Oxford — Public DomainDear ______:

Sorry if I burst your bubble when I said that Seminary can’t really be your church for the next few years.

It really depends on what kind of seminary you chose. Like it or not, choosing just about any Protestant seminary means your school doesn’t even try to be a church.

Don’t worry: seminary can still be a fantastic source of Christian community. It all comes down to knowing what kind of seminary you chose, and knowing what the Church is.

(We should probably be more accurate and say the seminary can’t be your “congregation,” since the “Church” is the bigger version of the Body of Christ, crossing all the boundaries of time, space, and culture. The Church is manifested in each congregation. Of course Christ’s life, the life of the Church, is found wherever we gather in his name, but it is not always reasonable to slip into saying a particular community is a church as we do with a congregation.)

There are lots of ways to categorize seminaries. If you are interested I’ll say more in another letter, but for now the key distinction is Protestant vs. Non-Protestant.

An Orthodox and Catholic Model

If you were training to be a Catholic or Orthodox priest, chances are your seminary would feel, and act, much more like a congregation — in the same way that a monastery feels and acts very much like a congregation.

Seminary would be a very intentional community, with multiple daily services for liturgical prayer, even if not the full cycle of monastic “hours.” The students would be immersed in the worship life of the larger Church, and that would be a key part of their sustenance and formation.

I know of at least one seminary of this kind that even celebrates the Eucharist every Sunday morning. They clearly aim to function as their students’ congregation — or their monastery.

And that can work when a seminary is built on on the model of monastic life. Time in seminary is time away from the world, focusing intensely on spiritual formation. As one friend described it, “It was ‘boot camp’ to prepare us for spiritual warfare.”

It won’t be a completely monastic experience, since it is also built around taking courses toward an academic degree, but that is where the community leans.

A Protestant Model

Every part of this is different in the typical Protestant seminary, like the one you chose. Here the balance tips the other way — toward being a graduate professional school.

Chapel worship in seminaries I’ve known ranges between once per week to every weekday. And worship in chapel is always optional — with either guilt or rebelliousness among non-attendees, and hand wringing about low attendance from the more devoted.

But it isn’t just the number of chapel services: In Protestant seminaries chapel worship is often a kind of workshop or learning lab, in which students experiment with styles and grow in skills.

(The result can be amazing or appalling. I will spare you my tragic and comic recollections.)

You may well think voluntary chapel with student leadership is the right approach, but it does highlight how our seminaries are less focused on spiritual formation. We let autonomous individuals choose their own path to growth.

If a Protestant seminary does try to make spiritual formation a central focus, there will be resistance. Both faculty and students will struggle.

Is it going to take away from academic priorities?

Will it be framed as a class? And how can it be graded?

Will all the professors have to participate — and will they be competent to do so?

Is the whole thing maybe just too Catholic?

Protestant seminaries tend to put a great deal of their emphasis on being graduate professional schools. Spiritual formation tends to take second place.

What kind of seminary is this?

This isn’t a critique. Seminaries have to live in two worlds: They serve their denominations, and the larger Church. But they are also degree-granting institutions, under the regulations of accrediting boards and governments.

So you need to think about what kind of seminary you are attending. You need to think about your own spiritual needs as you grow as a disciple and prepare for ministry.

If your seminary sees itself as a graduate professional school, and not as a church, where will you find the kind of full, broad experience of worship, formation, and mission that you intend to preach and teach to others once you graduate?

Find yourself a congregation, my friend.

Blessings,

Gary

The post What Kind of Seminary Is This? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

August 2, 2016

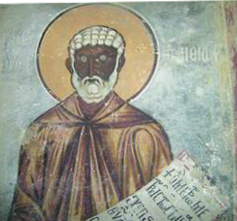

Stay in Your Cell (The Writer’s Inner Life)

Abba Moses the Black (Wikimedia Commons)

Abba Moses the Black (Wikimedia Commons)Here’s one of my favorite little stories from the sayings of the Desert Fathers:

In Scetis a brother went to Moses to ask for advice. He said to him “Go and sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.” (Quiet, 8)

Moses wasn’t talking about prison. The “cell” was a monk’s hut or cave in the 4th century Egyptian desert.

Stay In Your Cell

The advice was to stay put. Don’t go run errands.

The Desert Fathers and Mothers clearly didn’t always heed that advice: We have books of their sayings because they kept leaving their cells to hang out with each other.

Stay in the cell and they stayed in the game. That’s where the praying happened. That’s where they wrestled with their demons — all the issues that kept them from Christ.

Outside the cell? All distractions, all the time.

Here’s a saying from another desert father. This guy kept leaving his cell:

Hey look, a squirrel!

Just kidding.

But seriously, to keep at their main calling they had to avoid external distractions. Only then could they even notice all the inner obstacles that stood between their current state and new life in Christ.

If they didn’t notice the obstacles they surely would never conquer them.

The Writer’s Cell

Abba Moses’ advice to desert monks applies very well to the life of a writer. I too have work to do that takes inward focus. I need to stay in my cell.

The modern version of this is abbreviate “BIC.” That is, [keep your] Bum In [the] Chair.

I need to stay in one place and produce words. It doesn’t matter much if I write with a pen or a keyboard. But I do have to stay put.

Right now I’m in a cafe. Traffic goes by. People are talking in the background.

Hey look, a squirrel!

I need to heed Moses’ advice to stay in my cell. That is where the real action is. That is where I’ll fight the battles that matter.

If I don’t stay put, I am giving into one of the most deadly temptations: I don’t write down the words I came to write. I miss the battle I came here to fight. On purpose.

I often tell myself that it doesn’t matter where I write. To some degree that is true. There are bestselling authors who scribbled out their novels while commuting by bus or train.

I’ve written in countless cafes over the years. And in many libraries. And on a bench by the water. And of course at my very own desk.

But I notice that I list my very own desk last of all. That means I’m not very good at staying in my cell.

And even in my cell I can sabotage my writing life with clutter. There is the physical clutter of objects that grab my eye. There is also temporal clutter of chores and other demands.

Clutter makes it had to focus on the main thing I need to do.

My good news is that I have an excellent opportunity to change. I have a new space to turn into an office — my cell. I have choices to make about clutter and about what I do when I’m in there.

And about whether I go into my cell at all.

Moses has a good word for all of us who want to be productive and creative.

Stay in your cell. Do the work.

——

This post contains an affiliate link.

The post Stay in Your Cell (The Writer’s Inner Life) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.