Gary Neal Hansen's Blog, page 44

May 2, 2016

Interview with Rich Hansen, author of Paradox Lost

Paradox Lost on Amazon

Paradox Lost on AmazonI met Richard P. Hansen when I was giving a set of lectures on missional Christian community at First Presbyterian Church in Columbia Missouri where he was then pastor. I was really excited to hear about Paradox Lost, a book he was writing about paradox in the Christian faith — and now it is in print!

May 3 is the official release day. To celebrate the launch, I asked Rich if I could interview him about the project. Check it out, here, on his website, and on Amazon. (For a chance at a free copy, see below…)

Paradox Lost

GNH: Rich, congratulations on your new book! What’s the back story? What was the initial germ of the project?

RICH HANSEN: I first became fascinated by paradox about 30 years ago. In the 1990’s I wrote my Doctor of Ministry dissertation on how preaching biblical paradox helps Christians re-connect with the true God of the Bible, who is far more paradoxical and mysterious than often portrayed by the “fill in the blank” preaching style popular at the time. I then began writing journal articles about biblical paradox, which led eventually to the book.

GNH: Now that your book is all grown up and heading out into the world, what would you say is its mission? What do you want to happen in your readers’ lives?

RICH HANSEN: My passion is to engage with the growing number of people who want to wrestle with the paradoxes of life and faith rather than be handed pat answers or simplistic formulas. Thus, my primary audience is “thinking Christians”—believers who sense there is more still out there for them and want to keep exploring their faith. My secondary audience I would call “seekers”—folks interested in spiritual questions who may have been turned off by an anti-intellectual style of Christianity that did not take their doubts seriously.

GNH: For some readers, a book about paradox may sound too impractical or esoteric to interest them. How do you respond?

RICH HANSEN: For a sizable segment of American Christians, faith is about “practical answers to meet my felt needs”—i.e. God exists to solve my problems and make my life better. While God certainly does meet our needs, our most basic need according to Scripture is simply “that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3 NIV). By wrestling with the paradoxes I write about, I hope my readers will come to know more deeply a God who is more awesomely mysterious than a consumer-oriented, problem-solving God.

GNH: When you encounter something paradoxical in your faith, how does it strike you emotionally? At first glance is it more problem or blessing?

RICH HANSEN: In the book, I say encountering paradox in our spiritual journey is like stopping to watch a street performer on a crowded sidewalk. He or she compels our attention: we stop and watch. Paradox in life and Scripture is intriguing to me in the same way: it draws me in, partly because I cannot explain or solve it. It’s like the piece of scotch tape stuck to your finger you keep shaking it to remove, but never can.

GNH: What would be an example of a paradox that has strengthened your faith or pushed you to grow as a Christian?

RICH HANSEN: Two that have helped me immensely are the paradox of the Trinity (God is Three, yet One) and the paradox of the Incarnation (Jesus is 100% human, yet 100% God). Both have forced me to not settle for easy, simplistic answers in my faith. Both, oddly enough, have immense practical value for daily living once we stop trying to “solve” them and instead look through them. This drive to use biblical paradoxes as windows through which we see God more deeply and truly is the theme of the book.

GNH: Is there more than one kind of paradox?

RICH HANSEN: Paradox exists in the tension created by two seemingly opposite ideas. A distinctive feature of my book is that I identify three different genres or “orders” of biblical paradox. Each order has a unique tension between its opposing ideas. For example, one is like the tension in a tuning fork: two individual tines must vibrate in tension with one another to produce the note. Much of the book explores biblical examples of these three kinds of tension.

GNH: Are some paradoxes good and some not so good?

RICH HANSEN: I discovered in my research that psychology uses paradox as a therapeutic tool in both behavioral modification and family systems theory. Paradox leads to health when it prods us to action or we learn to live within the tensions it creates. However, paradox can also create emotionally unhealthy “double binds” which can lead to neurosis or other problems. In the book I discuss the differences between healthy and unhealthy paradox.

GNH: We’ve been talking about paradox in Scripture. But do you also address paradox outside the Bible?

RICH HANSEN: Absolutely! I work hard using biblical paradox to shine a spotlight on all the paradoxical tensions everyone constantly lives within every day. Indeed, I think ordinary life is quite paradoxical today on any number of fronts. For example, America is tragically polarized today precisely because we have lost the paradox the ancient Greeks knew well—truth often exists in the tension between opposite extremes. To live successfully in the 21st century, we will all need to become more comfortable living within paradox.

GNH: I know you’ve been a pastor in America and a theology professor in Ethiopia. Do Christians in the two cultures find different things paradoxical?

RICH HANSEN: As children of the Enlightenment, reason is king in the American worldview. We expect to understand everything in the Bible and have it all make sense; if it doesn’t, we often assume it’s the Bible’s fault, not our faulty thinking. In Ethiopia, on the other hand, tradition is king. Most Ethiopians rarely question received tradition—including the Bible—which means intellectual paradoxes may not be as quickly recognized or as troubling to them.

GNH: What was one surprising story on the road to publication?

RICH HANSEN: While I was teaching theology in Ethiopia, Dr. John Walton from Wheaton College came as a guest lecturer. As we became acquainted, I ventured to ask Dr. Walton if he’d offer some feedback on my book proposal. Unknown to me, he instead took the initiative to send the proposal to both Zondervan and Intervarsity Press. Where before my contacts with publishers (including Zondervan) had been fruitless, this time I had a signed contract in a couple months! It is a great example to me that God can indeed do the impossible!

Any advice for pastors out there (and others) who think they have a book inside them?

I would say, “keep going and trust God.” I gave up several times and put the book on the shelf, only to take it down and work on it again, sometimes years later. As the story above indicates, God’s timing is perfect. Perhaps it’s the Calvinist in me, but I believe if I keep knocking, if God wills it the door will be opened.

Thanks Rich! All blessings on you as your book launches May 3rd.

————

Richard Hansen has been a pastor in the PC(USA) for thirty years, and has taught theology at the Ethiopian Graduate School of Theology in Addis Ababa (2010-14), and as an adjunct professor at Mennonite-Brethren Biblical Seminary, Fresno, California. Connect with him online at his website, rich-hansen.com.

Richard Hansen has been a pastor in the PC(USA) for thirty years, and has taught theology at the Ethiopian Graduate School of Theology in Addis Ababa (2010-14), and as an adjunct professor at Mennonite-Brethren Biblical Seminary, Fresno, California. Connect with him online at his website, rich-hansen.com.

————

You can get a copy of Paradox Lost on Amazon by clicking here.

I’m giving away one free copy of Paradox Lost! Leave a comment below to enter. On 5/10/16 I’ll randomly choose one name from those who leave a comment.

(This post contains affiliate links.)

The post Interview with Rich Hansen, author of Paradox Lost appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 26, 2016

Finding Friends (Letters to a Young Pastor)

John Calvin by Holbein (public domain)

John Calvin by Holbein (public domain)Dear ____:

One of the best things that can happen to you in seminary is to broaden your friendship network. I’m glad you have been getting to know Christians whose backgrounds and opinions are very different from your own.

But actually, that is just the start.

Find some dead friends

I really hope you will pick up a handful of really excellent dead friends.

When you stand and say the Creed you affirm that you believe in “the communion of saints” and that, my friend, is not limited to people who are lucky enough to be alive at the same time as you.

In the first 2000 years of the Church’s life there have been some Christ followers who were pretty wise. They asked really good questions. They probed hard for answers. They left books behind.

In the course of your time in seminary, you need to pick up at least one or two Christian thinkers who can be your friends as the years of life and ministry roll on.

A suggestion: John Calvin

Let me propose one candidate: John Calvin (1509-1564). You haven’t taken a course on the Reformation yet, so let me tell you that most popular opinions about Calvin are worthless gossip.

You need to get to know Calvin first hand.

He wrote commentaries on most of the books of the Bible. If you read his thoughts as you prepare your sermons you will get to know him over time — as well as understanding your text better.

He also wrote a summary of biblical theology called The Institutes of the Christian Religion. If you are wondering what the Bible teaches on a topic, Calvin’s Institutes will give you a clear and coherent exposition.

Calvin is a wise companion on all kinds of things. He is thoroughly biblical and surprisingly fair-minded — and when you actually read him, he’s winsome.

Take prayer. It is a big topic for Calvin. His take is really different from what you find in many popular books on the topic today.

Three little quotations:

What is prayer really for?

The mind should be

freed from carnal cares and thoughts by which it can be called or led away from right and pure contemplation of God, and then not only devotes itself completely to prayer but also, in so far as this is possible, is lifted and carried beyond itself.” (Institutes 3.20.4)

Most Protestant writers today are all about getting God to give you what you pray for. We leave “contemplation” to the Catholics.

Calvin is convinced that God does hear and answer, but he sees that our relationship with God is the core issue. Prayer is about turning rightly toward God. That is contemplation.

It is not about getting what you want. It is about getting God.

Where does prayer come from?

What is the value of prayer? Who should pray? Where does prayer come from, especially if God knows our needs already?

On this Calvin discusses a passage he comes back to repeatedly, Joel 2:23, which was quoted by the Apostle Paul at Romans 10:13: “Whoever calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

Here’s Calvin:

…invocation arises from faith: for except God shines on us by his word, we cannot come to him; faith, then, is ever the mother of prayer.” (Commentary on Joel 2:23)

Calvin, like Luther, was convinced that faith is what really matters for salvation.

So, what is the evidence that you have faith? Prayer. If you have faith, then faith leads you to pray.

You know you are in need, and you trust that God can help. So you pray.

How do you learn to pray?

But how are you going to learn to pray?

Calvin had ideas about that too:

… calling upon God is one of the principal means of securing our safety, and … a better and more unerring rule for guiding us in this exercise cannot be found elsewhere than in The Psalms…” (Psalms Commentary, preface)

Luther said to learn from the Lord’s Prayer. Andrew Murray tried to take all the biblical imperatives about prayer and turn them into rules. Calvin says to look at the book of the Bible that is almost entirely prayers. Learn from the masters.

The thing is, in the Psalms God’s people pray about everything — heights of joy, agonies of despair, vengeful fits of rage. Some of it is pretty ugly, but it is all prayable — and God seems to have wanted it in the Bible.

So this letter wasn’t supposed to be all about prayer. Prayer is just an illustration of a topic on which Calvin can be very good company.

Find yourself some good dead friends. Keep me posted about who you decide to hang with.

Blessings,

Gary

————

From time to time I offer online classes on prayer, using great teachers like John Calvin as our guides — and using my award winning book Kneeling with Giants: Learning to Pray with History’s Best Teachers.

If you’d like to know about it next time one comes around, click the button below:

The post Finding Friends (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 21, 2016

Sex Addict Finds Recovery in Christ: St. Mary of Egypt

Girl in a Wood, Van Gogh, public domain

Girl in a Wood, Van Gogh, public domainLittle Girl Lost

Sometimes being a bit rebellious tips over into deeper trouble.

A 12-year-old girl, Mary, just on the cusp of young womanhood, ran away. This was not the tantrum that leads a kid to hide in the woods through dinner to punish her parents. Mary found her way to the big city.

She fell into her parents worst nightmare.

When she told her story to the old man, so many years later, she was perfectly clear: she had not been a prostitute. No, she had refused to take money for sex. But she had a lot of sex. A whole lot of sex.

From her telling of the story it sounds like luring men into sex gave her a high, a sense of power.

She sounds like what we would call a sex addict.

She begged or did other work for money. Sex brought opportunities. Sex was a tool. Sex was a pleasure.

Once she saw crowd by the shore. It looked like something fun was in the works, so she asked. Turns out they were going to set sail for Jerusalem — a significant trip from Alexandria in Egypt but not impossible.

They were going up for the celebration when the church venerated the cross of Christ — the real one, discovered not long before by St. Helena, Constantine’s mother.

They said she could come along if she had her own money for food.

Well that just sounded like a challenge.

She spent the voyage teaching the pious young men every kind of sexual debauchery she could think of. And she had studied the issue. For 17 years.

Lost Woman Found

But when they got to Jerusalem the fun dried up. She joined the throng going into the church to see the true cross, but somehow she could not cross the doorway.

She thought she was just being pushed, so she stepped back and tried again. No go. She simply couldn’t cross the threshold, though she tried again and again.

Something kept her from entering that church.

This give her time to ponder situation. She considered her way of life, her obsession. And now here she was, pushing her way, for fun, to get a casual view of the wood on which the son of God had died — for her.

These were thoughts that could cause even Mary to weep.

From where she stood she could see a holy icon of Jesus’ mother. Like countless millions of Christians, in that Mary’s eyes this Mary saw compassion — she saw someone who knew the Son of God and his love better than anyone in the world.

And so Mary prayed, confessing her sin. She promised to change. She asked help to really see Christ’s cross.

Now the way was clear. Mary came in. She worshiped.

A message reached her tear-softened heart:

Cross the Jordan.

Mary made one stop along the way: At the edge of the river she received communion at a church dedicated to John the Baptist. She bought three loaves of bread. She crossed the Jordan, into the wilderness beyond.

Sex Addict Finds Recovery

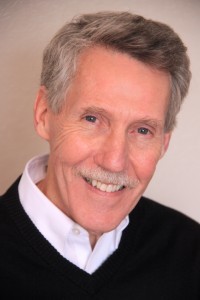

Icon of Mary of Egypt (Mstera, 19th c.)

Icon of Mary of Egypt (Mstera, 19th c.)There in the desert she spent 47 years in a recovery program of her own devising.

She nibbled her three loaves of bread for a very long time until they were gone. Then she ate what plants she could find. She prayed. She saw no one.

Like all the desert fathers and mothers, in solitude she battled her demons. When the longing for sex struck she lay on the ground in prayer until it passed — it might take a day or two.

Her story would have been unknown, as surely many great saints are unknown, but God prompted an old monk to enter her part of the desert one year during Lent.

The naked, sunburned, old woman asked for his cloak so she could approach for his blessing.

He suspected she was a holy person when somehow she knew his name and monastery. He insisted she bless and pray for him.

He knew for sure she was holy when he looked up to find her praying for him two feet off the ground.

At her request he promised to return in a year, at the end of the next Lent, bringing the Eucharist. He did so. She died later that day.

————

St. Mary of Egypt (c. 344-c. 421) is celebrated on the fifth Sunday of Lent in Orthodox churches. Most saints are honored on a particular date of the calendar year. St. Mary is such a witness to the life of repentance, and of transformation by Christ from sinner to saint, that she is always honored at the height of the holy season of repentance, just before Palm Sunday. You can read her story in the words of St. Sophronius of Jerusalem (560-638) by clicking here.

————

St. Mary of Egypt described her life in terms that today would call addiction. She bears witness that in Christ sex addicts, and all addicts, can find grace and healing.

You can learn about Sex-Addicts Anonymous by clicking here.

You can learn about Alcoholics Anonymous by clicking here.

You can learn about Narcotics Anonymous by clicking here.

You can learn about Gamblers Anonymous by clicking here.

You can learn about Overeaters Anonymous by clicking here.

The post Sex Addict Finds Recovery in Christ: St. Mary of Egypt appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 14, 2016

Inerrant or Infallible or What? (Letters to a Young Pastor)

cc by Scott Akerman 2.0

cc by Scott Akerman 2.0Dear ______:

So good to hear from you! Glad to hear that you are doing well. Summer plans?

The confusing spot you are in is, in a way, a lovely benefits of a residential seminary: you regularly talk with other people who are in the thick of theological exploration.

They come from different backgrounds. They have different assumptions. They may be chewing on classes you haven’t taken. You’ll rarely find yourself in such a rich stew.

Now you are hearing people throw around technical terms about the Bible. Some say it is

inerrant.

Some say it is

infallible.

You wisely ask

What’s up with that?

Inerrant or Infallible

Google has led you in the right direction in terms of current usage. These words are a morass and a muddle, largely because American Christianity is theologically weak and historically agnostic.

I always start with original usage for “inerrant.” It comes from the “Princeton Theology” in late 19th century fundamentalism. Hodge & co. argued that the “original autographs” of Scripture, the manuscripts penned by prophets and apostles, were free of error — like they were 100% true in doctrine and facts. Great guys, Hodge, & co., but that’s not very helpful. The original manuscripts of every book of the Bible are long gone.

In current use the term can mean that, or just about anything else, depending on the theological leanings and education of the user. I see Seminarians regularly use “inerrant” in draft statements of faith when they really mean to say the Bible is “authoritative,” “reliable,” or “true.” (Those are three excellent words to use about Scripture, by the way).

“Infallible” has a different back story. You will find it in the Westminster Confession, but not primarily about the Bible. It says that there is an infallible rule for interpreting Scripture (Scripture itself) not that the Scriptures are infallible.

More emphatically it says God’s knowledge is infallible, and that you and I can be given infallible assurance of faith.

(In 1903 the Northern Presbyterian Church added a section on the Holy Spirit that does sound more like Scripture is infallible, but this was not in the original WCF.)

In common usage, people seem to use infallible to mean that their English translation of the available Greek and Hebrew manuscripts is without error of fact — effectively meaning the KJV or NIV or whatever is inerrant. Silly again.

How about “reliable” and “true”?

Westminster is wiser in what it says about the Bible. It says the Bible is our

rule of faith and life.

Scripture is our “rule,” not in the sense of a book of laws, but as a yardstick — a ruler. It lets you find out what is straight and measure things accurately.

As the rule of faith, Scripture’s subject matter is theology. It will guide you truly and reliably as you seek to know who God is and who we are in relation to God. It will teach you clearly what you need to know to find salvation.

As the rule of life, Scripture’s subject matter is ethical; it is about the way we live as God’s people. We know that the whole shebang is summarized as loving God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, and loving neighbors as ourselves. Scripture, read broadly and deeply, will fill in useful details on how to do that.

I’ve always admired the wisdom of John R.W. Stott on this. He didn’t like either “inerrant” or “infallible” on the grounds that it is unhelpful to start Christian theology with a double negative. He said that he preferred to say Scripture is true in what it affirms.

So on its subject matter, theology and ethics, the Bible is reliable and true. I’m all over that.

Gotta go. Thanks for the good question!

Errantly and fallibly yours,

Gary

————

Knowing the Bible Well Enough to Tell its Story

Want to know what the Bible really does teach, and make it your own? No better way to start than by getting a solid grasp on the Big Story that holds the Little Stories of the Bible together.

When you know that Big Story well enough to tell it yourself, following Jesus make more sense — because you come to see how the Bible makes sense. It is a huge help in being a confident, competent disciple.

I would love to help you get a confident working knowledge of the Bible so you can tell its story to your kids — or to anybody else actually.

I’m dreaming up a class to help you know the Bible like you’ve never known it before. Just click the button and I’ll keep you posted.

Send me info about that Bible class!

The post Inerrant or Infallible or What? (Letters to a Young Pastor) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 12, 2016

“Eat This Book” — online at the Presbyterian Outlook

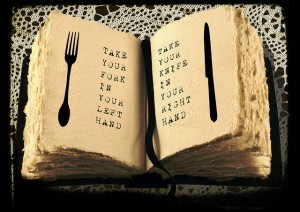

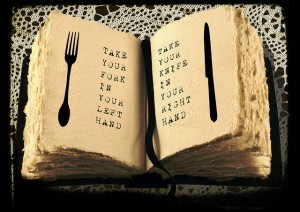

cc by Caroline 2.0

cc by Caroline 2.0I recently had the privilege of writing the “Benedictory” essay in The Presbyterian Outlook. Usually these are behind a pay wall for subscribers only, but because my friend Scott Black Johnson of 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church in Manhattan (check out their cool welcome video here) asked to share it with his congregation, they opened it up — at least temporarily!

Eat this Book

Here’s how it starts:

I GREW UP IN THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH. The liturgies of the Book of Common Prayer planted good seeds and grew deep roots for the conscious faith that blossomed later. Even after centuries, Thomas Cranmer’s work of genius nourishes life with the theological richness and beauty of its language. I recommend it often as a resource for prayer.

One of my favorite prayers in the Book of Common Prayer puts words on my longing for all members of the PC(USA):

Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them,…

————

Knowing the Bible Well Enough to Tell its Story

If you do “read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” the Bible, its stories become your own.

When you can tell those stories following Jesus make more sense — because you come to see how the Bible makes sense. It is a huge help in being a confident, competent disciple.

I would love to help you get a confident working knowledge of the Bible so you can tell its story to your kids — or to anybody else actually.

I’m dreaming up a class to help you know the Bible like you’ve never known it before. Just click the button and I’ll keep you posted.

Send me info about that Bible class!

The post “Eat This Book” — online at the Presbyterian Outlook appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 7, 2016

Finding a Good Children’s Bible

cc 2.0 by Kelly Sikkema

cc 2.0 by Kelly SikkemaReading to my children is one of my great joys as a parent.

Helping my children know, and love, and trust God is one of my great hopes as a Christian.

Enter that sometimes vexing genre, the “Children’s Bible.”

On many levels a children’s Bible is a great idea.

Reading the Bible, uncut, to my five and seven year old children is a non-starter. Or maybe a non-finisher is the better way to put it. There are vast swaths of the law that lack, shall we say, narrative drive.

But a children’s Bible, a selective, child-friendly book that tells the stories that hold the Bible together, sounds great.

They’ll see the unfolding drama of salvation at their own level. Then when they are ready to read the actual Bible, they will already know the outline.

But why, then, are children’s Bibles so often kind of awful?

Well no need to go into a rant on the topic, but I’ll just say that I’ve seen some that turn the gritty reality of the drama of salvation into cloying sweetness. Or God’s promise of grace in Christ can subtly turn into law for behavior management.

Let’s just say many if them fail my “wince test.”

Three Children’s Bibles

Let me tell you about three that have had some success in our house. I’ll take them in order of discovery.

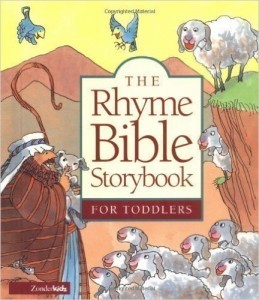

Rhyme Bible Storybook on Amazon

Rhyme Bible Storybook on AmazonYou might fear that adding rhyming to every page of a children’s Bible increases the risks. A disproportionate number of Christians do believe they are gifted in the poetic line. Faith apparently absolves them from the need for attend to meter.

In this case the only risk is that you will have to spend too many hours reciting those rhymes. I believe we actually wore the cover off from use.

The rhymes are fun and carry the story very well.

In the beginning

God made the light.

The light was for day

and the dark was for night.

There is a newer edition, it seems, with different illustrations. I absolutely love the illustrations in the version I’ve linked to above. They are whimsical and they evoke the emotions of the stories. And that is not always the case in children’s Bibles. Many have pictures as cheesy as — well, as cheesy as Christian art often is.

The book is succinct: 12 Old Testament stories and 14 New Testament. I was amazed how well the key stories and overall narrative were communicated.

Over and over. Night after night after night. All through toddlerhood. Then suddenly, we were done.

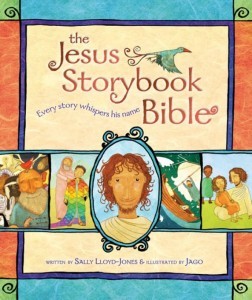

The Jesus Storybook Bible on Amazon

The Jesus Storybook Bible on AmazonNo rhymes here, in case that is a relief to you, and a much fuller telling of each story. But the great feature of The Jesus Storybook Bible is explained in the subtitle: Every Story Whispers His Name. This is a children’s Bible with a clear theology of Scripture.

It is not merely that every story matters, or even that the whole story matters — though both statements are true. The Jesus Storybook Bible sees the whole of Scripture through its proclamation of Jesus.

Throughout its 21 Old Testament stories and 23 New Testament stories, Jesus the “rescuer” is always under consideration: he is the one who was hoped for, promised and expected. He is the one who was present and active. He is the one who is remembered and to whom followers bore witness.

In the beginning there was nothing.

Nothing to hear. Nothing to feel. Nothing to see.

Only emptiness. And darkness. And … nothing but nothing.

But God was there. And God had a wonderful Plan.

Because of seeing the whole Bible through the lens of Jesus, the book hangs together as a book better than most children’s Bibles. And more importantly, it helps parents and their kids begin to read the Bible as Christians, since this is the ancient and traditional understanding of how the Bible works.

The pictures are fun. Jago’s illustrations don’t aim for realism but they create a cultural world in which to see the Bible. They partner well with the stories, and can take the reader farther than the words would on their own.

If reading books gave us frequent flyer miles, we would have a great vacation from this one by now. Since they don’t, we’ll just keep reading it. It remains a pleasure for both parents and kids.

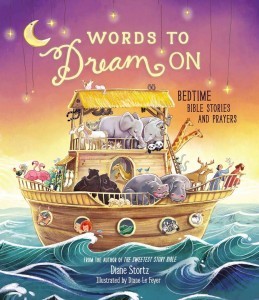

Words to Dream On, on Amazon

Words to Dream On, on AmazonThis is the most recent addition to our collection. By way of full disclosure, I received a copy in a giveaway on the author’s agent’s blog.

With 26 Old Testament stories and 26 New Testament this book gets into more specific parts of the narrative than the others reviewed here. I’ve not done a word count, but my sense is that it would be high.

There is less of a clear theological center to the telling of the Bible’s story here. The stories are presented chronologically. That is true to the nature of the Bible’s own presentation, so one could argue the approach is especially appropriate.

Make-believe stories often begin “once upon a time…” But God’s true story starts like this: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.”

There is, then a combination of retelling and paraphrase. There is a bit more here in each story told as compared to children’s Bible reviewed above. A few more questions get answered about each story, even if the book as a whole is not carried forward in plot and character development. I suspect this is why one of my children is currently prodding me to read this book in particular.

The illustrations are attractive more than evocative, some a bit Disneyesque.

Trying to simply tell the story of the Bible at a kid’s level presents some challenges. Some bits that would be hard to explain to children are simply skipped here — scenes in Jacob’s and David’s lives come to mind. This leaves some plot holes which, strangely, are more noticeable here than in the shorter books reviewed above.

I’ve talked only about the stories, not about the book’s other distinctive features. The stories are the best part. Every story is preceded by a Bible verse, but they are rarely from the story being told. Each concludes with a blessing and a prayer, but the blessings are more declarations of truths.

Telling Your Children the Bible’s Story

Each night when we turn the lights out I tell my kids a Bible story — without a book to help. We start with creation, move through the Old Testament night by night, then Jesus arrives and we move through the Gospels all the way through Acts and the Revelation.

I would love to help you get a confident working knowledge of the Bible so you can tell its story to your kids — or to anybody else actually. It is a huge help in being a confident, competent disciple.

I’m dreaming up a class to help you know the Bible like you’ve never known it before. Just click the button and I’ll keep you posted.

Send me info about that Bible class!

————

There are affiliate links in this post

The post Finding a Good Children’s Bible appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

April 5, 2016

Why Did Jesus Have to Die? (Heidelberg Catechism Q. 40)

Pieta, Michelangelo (photo Giulio Menna, cc 2.0)

Pieta, Michelangelo (photo Giulio Menna, cc 2.0)We are in the season of Easter. This is when, of all seasons of the year, our attention needs to focus on the resurrection of Christ. But we find our selves asking instead “Why did Jesus have to die?”

Ours tends to be a “Good Friday” faith. We see the empty tomb and we think “The Cross put him in there.”

So why not ask the Good Friday question directly? Maybe Easter will give us enough hope to face it.

Why did Jesus have to die?

The Heidelberg Catechism (the much loved 450 year old summary of biblical Christianity about which I’ve not blogged in too long) puts it as plainly as can be:

40 Q. Why did Christ have to suffer death?

Why indeed. Couldn’t he have simply begun to reign as King, as the disciples seemed to hope? Couldn’t someone who poured out so much love to so many at least avoid death by a lynch mob?

Here’s the Catechism’s answer:

A. Because God’s justice and truth require it:

nothing else could pay for our sins

except the death of the Son of God.

You can take that very brief statement in a number of ways. Which one you choose will depend on the kind of drama you see unfolding in the life of Jesus.

Christ’s Drama as a Tragedy

Our hope that Christ might have avoided the cross comes from seeing a merely human drama playing out:

Jesus was a wonderful man, but just a man.

The authorities somehow turned against him and that is a tragedy.

The Catechism assumes a bigger drama.

Christ’s Drama as a Western

Christ’s drama might be a “western,” but there are no Cowboys involved. Okay, what I mean is that there is a Western (i.e. European as opposed to Asian) way of thinking about the story.

If you circle the words “justice” and “pay” and “death” you have the outline of the usual Western theological drama. It is rooted in St. Anselm’s writings long before the Reformation:

Our sin is a great crime, a breach of God’s law, and must be punished by death.

God the King has been dishonored, and the infinite price must be paid.

Christ alone, God incarnate, is the only one whose death can pay it.

Christ’s Drama as a Mystery

You can think of Christ’s drama as a “mystery” too, but without need for a detective to figure out whodunnit.

The clues might come to mind if you circle the words “God’s” and “truth.”

Picture humanity created for TRUE life, communion with God.

Picture humanity choosing an UNtrue life, a cursed life.

We chose what God had told us would lead to bad consequences back in the garden: we turned away from intimacy with God in the foolish attempt to know, really experientially know, not only good but evil.

God had said death would come if we chose that, and it did.

Then circle “death” and “Son of God.”

The second Person of the Trinity, the eternal Son of God willingly came to us, became human, specifically so that he could take the curse for us.

Taking the death that was humanity’s consequence, Christ freed us from death.

That’s another biblical, and very traditional, Christian approach to the question of why Jesus had to suffer death. He chose the cross “for the joy set before him” (Hebrews 12:2) of bringing us life instead of death.

It is not just that the empty tomb implies the cross.

The cross happened so that we could get to the empty tomb.

The post Why Did Jesus Have to Die? (Heidelberg Catechism Q. 40) appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 25, 2016

Good Friday: Mystery and Paradox

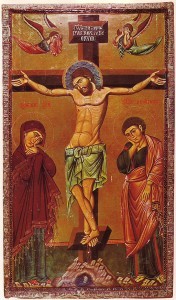

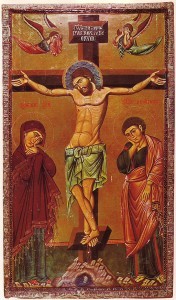

Crucifixion Icon, Sinai, 13th Century

Crucifixion Icon, Sinai, 13th CenturyLast year I posted on the meaning of “Good” in “Good Friday.” Today my thoughts go more to the stunned awe that the Cross of Christ inspires.

My love for Jesus always makes a reading of the Passion painful, especially read aloud in worship, and most especially if I am the one doing the reading.

Mystery and Paradox

But there is more there, more mystery and paradox, than my personal grief at Jesus’ suffering.

One piece of music that helps me feel this profoundly is an Orthodox hymn that comes in the Good Friday cycle of services.

In a series of parallel phrases like an Old Testament Psalm, the hymn portrays the events of Christ’s passion on a much bigger canvas than personal sadness: the contrast is to Christ’s place in the Godhead, and his role in creation and redemption

Singing Good Friday

My friend Fr. Dustin Lyon first directed me to this meditation, sung in the haunting music of “Tone 6” and with bell-like clarity by Fr. Apostolos Hill. Here is a transcription

Today is suspended upon the tree, He who suspended the land upon the waters.

Today is suspended upon the tree, He who suspended the land upon the waters.

Today is suspended upon the tree, He who suspended the land upon the waters.

A crown of thorns crowns Him who is the King of the angels.

He is wrapped about with the purple of mockery, who wrapped the heavens with clouds.

He received smitings, he who freed Adam in the Jordan.

He is transfixed with nails, who is the Son of the Virgin.

We worship Thy passion O Christ.

We worship Thy passion O Christ.

We worship Thy passion O Christ.

Show us also Thy glorious resurrection.

You can hear this amazing hymn on this YouTube video — the images are all icons and Fr. Apostolos Hill is the audio.

And if you find yourself wanting the CD, you can get it on Amazon through this affiliate link.

May your meditations on the Cross be rich with blessing as you prepare for Christ’s glorious resurrection.

The post Good Friday: Mystery and Paradox appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

March 23, 2016

Lent: On Repentance

Return of the Prodigal Son, Pompeo Batoni (public domain)

Return of the Prodigal Son, Pompeo Batoni (public domain)For Protestant and Catholic Christians this is Holy Week. That means you still have a few days to take a dive into repentance.

Chances are that doesn’t sound like such a great offer. Especially in the Protestant world we have a pretty hard time with repentance.

We associate the word “repentance” with our lunatic fringe, carrying signs about the end of the world.

And in our post-freudian post-modern culture we tend to assume that there is nothing, really to repent of. We aim for positive, affirming attitudes at all times.

Sometimes in worship we even do a little liturgical side-step where the “prayer of confession” doesn’t actually admit to any wrongdoing.

Things are a bit different in the East.

On the first Monday night of Lent I found myself at an Orthodox church for the service known as “Great Compline.”

The sermon came at the end. The priest was glowing. He had a great opening:

I don’t know about you but I couldn’t wait to get to Church tonight! It is LENT!

Here was someone convinced that Lent was where the real action happened. He looked forward to the 40 day privilege of repentance, journeying with his Church to new life in Christ.

Lent is so important in the East that they actually spend several weeks focusing their worship on getting ready for it.

The Sunday of the Prodigal Son

The second of those preparatory Sundays of Orthodox pre-Lent is worth a thought here in the last days of Western Lent.

They call it “The Sunday of the Prodigal Son.” The hymns explore the great Parable Jesus told (Luke 15:11-32) in which a greedy son asked for his inheritance early, wasted it, and then sought to return to his father as a servant rather than starve.

You can preach it the story of the waiting Father, who eagerly welcomes his lost son again.

You can preach it as the story of the grumpy older brother who feels jealous that the guy who acted badly gets welcomed back with a party.

Or you can focus on the prodigal, the one who did everything wrong but repents and receives grace.

That third option is the one you find in the Orthodox hymns.

Repentance

The hymns place every worshipper into the role of the one who totally messed up and comes back to ask forgiveness.

As the Prodigal Son I come to Thee, merciful Lord. I have wasted my whole life in a foreign land; I have scattered the wealth which Thou gavest me, O Father. Receive me in repentance, O God, and have mercy upon me. (Lenten Triodion, p. 113)

They have each worshipper look for and find the feelings of sorrow coming from the prodigal’s wrong choices:

I have wasted the wealth which the Father gave to me, and in my wretchedness I have fed with the dumb beasts. Yearning after their food, I remained hungry and could not eat my fill. But now I return to the compassionate Father and cry out with tears: I fall down before Thy loving-kindness, receive me as a hired servant and save me. (Lenten Triodion, p. 113)

It is an explicit prayer of confession:

O Jesus my God, as the Prodigal Son now accept me also in repentance. All my life I have lived in carelessness and provoked Thee to anger. (Lenten Triodion, p. 115)

And in a self-searching akin to what you find in a 12 Step program, they all admit that choices have had consequences:

Utterly beside myself, I have clung in madness to the sins suggested to me by the passions. But accept me, O Christ, as the Prodigal. (Lenten Triodion, p. 116)

The wealth of blessings which Thou gavest me, heavenly Father, have I wrongly wasted and become the slave of strangers. Therefore I cry aloud to Thee: I have sinned against Thee; receive me like the Prodigal of old, opening Thine arms to me. (Lenten Triodion, p. 117)

So let’s go for it, my friend. Let’s find the truth and tell the truth about ways we’ve turned the wrong way. God is there waiting, eagerly. That’s what Lent is all about.

————

There are affiliate links in this post.

The post Lent: On Repentance appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.

February 23, 2016

Lent: On Humility

CC by Ted-SA 2.0

CC by Ted-SA 2.0We in the West have already had two of the six Sundays of Lent.

The East is just ramping up.

They start on a different schedule, and each of the four Sundays before Lent begins has its own clear focus. It is all about getting ready for Lent.

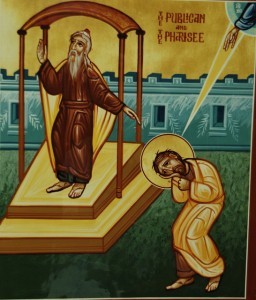

The Pharisee & The Publican

It started this week with “The Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee.” The morning prayer service (“Mattins” or “Orthros”) that comes before the Divine Liturgy is filled with hymns and prayers diving deep into the story Jesus told:

Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax-collector.

The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, “God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax-collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.”

But the tax-collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast and saying, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other; for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted. (Luke 18:10-14 NRSV)

This Lent I’m praying through the Orthodox service book for the season, The Lenten Triodion. (I got mine as a gift. If you don’t happen to have a friend who is an Orthodox priest with an extra copy, Amazon carries it.)

And I have to say, it is pretty amazing to see the way the whole service is woven together to help worshippers take this biblical text seriously. There is no sermon — but singing and praying these words yourself takes the Word deep into your heart.

On Humilty

So, whether as a Lenten exercise or as preparation for Lent, consider the virtue of humility which Christ praises. Here are few short segments of the canticles on the theme from the Lenten Triodion:

Through parables leading all mankind to amendment of life, Christ raises up the Publican from his abasement and humbles the Pharisee in his pride. (p. 102)

Every good deed is made of no effect through foolish pride, while every evil is cleansed by humility. In faith let us embrace humility and utterly abhor the ways of vainglory. (p. 102)

From the dung-hill of the passions the humble is lifted up on high, while the proudhearted suffers a grievous fall from the height of the virtues: let us flee from his evil ways. (p. 103)

The Word who humbled Himself even to the form of a servant, showed that humility is the best path to exaltation. Every man, then, who humbles himself according to the Lord’s example, is exalted on high. (p. 104)

There is more. (A lot more.) But even a tiny sample startles me to attention: This is not any “works righteousness.” This is eager pursuit of the heart Christ praised — the attitude Christ said led to the sinner being “justified.”

And justification is a good Protestant goal, eh?

The Jesus Prayer

There is another great reason the Orthodox love this parable — something that shows how the Orthodox are taught to strive to live according to its teaching. You see it in another one of these canticles:

As the Publican let us also beat our breasts and cry out in compunction, ‘God be merciful unto us sinners’, that like him we may receive forgiveness. (p. 103)

That’s the heart, one of the biblical roots, of the Jesus Prayer, the key practice of Orthodox prayer life: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me” and as many end the prayer, “a sinner.”

If you are interested in exploring the Jesus Prayer (and it is really a rich approach to prayer) check out my chapter about the classic book The Way of a Pilgrim in Kneeling with Giants.

————

I’d love to hear from you in the comments: What makes for healthy humility in the Christian life?

(There are affiliate links in this post.)

The post Lent: On Humility appeared first on Gary Neal Hansen.