Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 33

January 27, 2014

A Note To Self

“To be casual, relaxed, the person in every situation who tells everyone else not worry about it. Not the other way around–the agitator, the paranoid, the worrier or the irrational. Be the calm, not the liability.” Found in a bin of papers, dated 6/24/10

January 24, 2014

How And Why To Keep A “Commonplace Book”

The other day I was reading a book and I came across a little anecdote. It was about the great Athenian general Themistocles. Before the battle of Salamis, he was locked in a vigorous debate with a Spartan general about potential strategies for defeating the Persians. Themistocles was clearly in the minority with his views (but which ultimately turned out to be right and saved Western Civilization). He continued to interpret and contradict the other generals. Finally, the Spartan general threatened to strike Themistocles if he didn’t shut up and stop. “Strike!” Themistocles shouted back, “But listen!”

When I read this, I immediately began a ritual that I have practiced for many years–and that others have done for centuries before me–I marked down the passage and later transferred it to my “commonplace book.” Why? Because it’s a great line and it stood out to me. I wrote it down, I’ll want to have it around for later reference, for potentially using it in my writing or work, or for possible inspiration at some point in the future.

In other posts, we’ve talked about how to read more, which books to read, how to read books above your level and how to write. Well, the commonplace book is a thread that runs through all those ideas. It what ties those efforts together and makes you better at each one of them. I was introduced and taught a certain version of this system by Robert Greene and now I am passing along the lessons because they’ve helped me so much.

What is a Commonplace book?

A commonplace book is a central resource or depository for ideas, quotes, anecdotes, observations and information you come across during your life and didactic pursuits. The purpose of the book is to record and organize these gems for later use in your life, in your business, in your writing, speaking or whatever it is that you do.

Some of the greatest men and women in history have kept these books. Marcus Aurelius kept one–which more or less became the Meditations. Petrarch kept one. Montaigne, who invented the essay, kept a handwritten compilation of sayings, maxims and quotations from literature and history that he felt were important. His earliest essays were little more than compilations of these thoughts. Thomas Jefferson kept one. Napoleon kept one. HL Mencken, who did so much for the English language, as his biographer put it, “methodically filled notebooks with incidents, recording straps of dialog and slang” and favorite bits from newspaper columns he liked. Bill Gates keeps one.

Not only did all these famous and great individuals do it. But so have common people throughout history. Our true understanding of the Civil War, for example, is a result of the spread of cheap diaries and notebooks that soldiers could record their thoughts in. Art of Manliness recently did an amazing post about the history of pocket notebooks. Some people have gone as far as to claim that Pinterest is a modern iteration of the commonplace book.

And if you still need a why–I’ll let this quote from Seneca answer it (which I got from my own reading and notes):

“We should hunt out the helpful pieces of teaching and the spirited and noble-minded sayings which are capable of immediate practical application–not far far-fetched or archaic expressions or extravagant metaphors and figures of speech–and learn them so well that words become works.”

How to Do It (Right)

-Read widely. Read about anything and everything and be open to seeing what you didn’t expect to be there–that’s how you find the best stuff. Shelby Foote, “I can’t begin to tell you the things I discovered while I was looking for something else.” If you need book recommendations, these will help.

-Mark down what sticks out at you as you read–passages, words, anecdotes, stories, info. When I read, I just fold the bottom corners of the pages. If I have a pen on me, I mark the particularly passages I want to come back to. I used to use flag-it highlighters, which can be great.

-Again, take notes while you read. It’s what the best readers do, period. it’s called “marginalia.” For instance, John Stuart Mill hated Ralph Waldo Emerson, and we know this based on his copies of Emerson’s books where he made those (private) comments. You can also see some of Mark Twain’s fascinating marginalia here. Bill Gates’ marginalia is public on a website he keeps called The Gates Notes. It’s a way to have a conversation with the book and the author. Don’t be afraid to judge, criticism or exclaim as you read.

-Wisdom, not facts. We’re not just looking random pieces of information. What’s the point of that? Your commonplace book, over a lifetime (or even just several years), can accumulate a mass of true wisdom–that you can turn to in times of crisis, opportunity, depression or job.

-But you have to read and approach reading accordingly. Montaigne once teased the writer Erasmus, who was known for his dedication to reading scholarly works, by asking with heavy sarcasm, “Do you think he is searching in his books for a way to become better, happier, or wiser?” In Montaigne’s mind, if he wasn’t, it was all a waste. A commonplace book is a way to keep our learning priorities in order. It motivates us to look for and keep only the things we can use.

-After you finish the book, put it down for a week or so. Let it percolate in your head. Now, return to it and review all the material you’ve saved and transfer the marginalia and passages to your commonplace book.

-It doesn’t have to just be material from books. Movies, speeches, videos, conversations work too. Whatever. Anything good.

-Actually writing the stuff down is crucial. I know it’s easier to keep a Google Doc or an Evernote project of your favorite quotes…but easy has got nothing to do with this. As Raymond Chandler put it, “When you have to use your energy to put those words down, you are more apt to make them count.” (Disclosure: for really long pieces, I’ll type it up and print it out).

-Technology is great, don’t get me wrong. But some things should take effort. Personally, I’d much rather adhere to the system that worked for guys like Thomas Jefferson than some cloud-based shortcut.

-That being said, I don’t think the “book” part is all that important, just that it is a physical resource of some kind. If you do want a book, Moleskines are great and so are Field Notes.

-I use 4×6 ruled index cards, which Robert Greene introduced me to. I write the information on the card, and the theme/category on the top right corner. As he figured out, being able to shuffle and move the cards into different groups is crucial to getting the most out of them. Ronald Reagan actually kept quotes on a similar notecard system.

-For bigger projects, I organize the cards in these Cropper Hoppers. It’s meant for storing photos, but it handles index cards perfectly (especially when you use file dividers). Each of the books I have written gets its own hopper (and you can store papers/articles in the compartment below.

-These Vaultz Index Card boxes are also good for smaller projects (they have a lock and key as well).

-Don’t worry about organization…at least at first. I get a lot of emails from people asking me what categories I organize my notes in. Guess what? It doesn’t matter. The information I personally find is what dictates my categories. Your search will dictate your own. Focus on finding good stuff and the themes will reveal themselves.

-Some of my categories for those who are curious: Life. Death. Writing. Stoicism. Strategy. Animals. Narrative Fallacy. Books. Article Ideas. Education. Arguing with Reality. Misc.

-Don’t let it pile up. A lot of people mark down passages or fold pages of stuff they like. Then they put of doing anything with it. I’ll tell you, nothing will make your procrastinate like seeing a giant pile of books you have to go through and take notes on it. You can avoid this by not letting it pile up. Don’t go months or weeks without going through the ritual. You have to stay on top of it.

-Because mine is a physical box with literally thousands of cards, I don’t carry the whole thing with me. But if I am working on a particular section of a book, I’ll take all those cards with me. Or when I was working on my writing post for Thought Catalog, I grabbed all the “writing” cards before I hopped on a flight and through the post together while I was in the air.

-It doesn’t have to be just other people’s writing. One of my favorite parts of The Crack Up–a mostly forgotten collection of materials from F. Scott Fitzgerald published after his death–is the random phrases and observations he made. They are aphorisms without the posturing that comes with writing for publication. So many of my notecards are just things that occurred to me, notes to myself in essence. It’s your book. Use it how you want.

-Look at other people’s commonplace books. It’s like someone is separating the wheat from the chaff for you. Try a Google Books search for “Commonplace Book”–there is great stuff there.

-Use them! Look, my commonplace book is easily justified. I write and speak about things for a living. I need this resource. But so do you. You write papers, memos, emails, notes to friends, birthday cards, give advice, have conversations at dinner, console loved ones, tell someone special how you feel about them. All these are opportunities to use the wisdom you have come across and recorded–to improve what you’re doing with knowledge passed down through history.

-This is a project for a lifetime. I’ve been keeping my commonplace books in variety of forms for 6 or 7 years. But I’m just getting started.

-Protect it at all costs. As the historian Douglas Brinkley said about Ronald Reagan’s collection of notecards: “If the Reagans’ home in Palisades were burning, this would be one of the things Reagan would immediately drag out of the house. He carried them with him all over like a carpenter brings their tools. These were the tools for his trade.” I couldn’t have put it better myself.

-Start NOW. Don’t put this off until later. Don’t write me about how this is such a good idea and you wish you had the time to do it too. You do have the time. But start, now, and stop putting it off. Make it a priority. It will pay off. I promise.

If anyone wants to post photos of their Commonplace Book or describe their personal method–go for it (or email it to me).

This post originally ran on ThoughtCatalog.com. Comments can be seen there.

January 6, 2014

9 Timeless Business Virtues From A 19th Century Self-Made Millionaire

Below are some lessons from one of my favorite books.

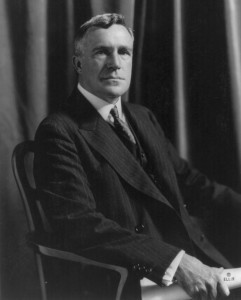

If Cyrus the Great can give us 9 Lessons On Power And Leadership From Genghis Khan, why can’t pithy advice on virtues and manhood be found in the century-old letters of a self-made millionaire? Fortunately, newspaper editor George Horace Lorimer complied all that for us, collecting and publishing the early 1900′s bestseller: Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son by John “Old Gorgon” Graham, the Chicago-based pork and finance baron.

by John “Old Gorgon” Graham, the Chicago-based pork and finance baron.

George Horace Lorimer Credit: Library of Congress

The words may be more than 100 years old, but they feel like they were written just last week. Perhaps that’s because today we have another Graham with us, Paul Graham, self-made millionaire, founder of YCombinator and investor in hot tech start ups from AirBnB to Reddit and Dropbox, who believes that young people should be thoughtful, start start-ups, and be their own boss. His essays have become incredibly popular with entrepreneurs and programmers looking for a different path—the path of self-sufficiency and great wealth. Well, the original John Graham preached the same message, famously reminding ambitious young men that they should: “Mind your own business; own your own business and run your own business.”

His letters, like Graham’s essays, are not only timeless (and completely under-appreciated) classics, but an incisive and edifying tutorial in entrepreneurship, responsibility, and leadership.

On Decisiveness

“The man who can make up his mind quick, makes up other people’s minds for them. Decision is a sharp knife that cuts clear and straight and lays bare the fat and the lean; indecision is a dull one that hacks and tears and leaves ragged edges behind it.”

On Rules

“Some men think that rules should be made of cast iron; I believe they should be made of rubber, so they can be stretched to fit any particular case and then spring back into shape again. The really important part of a rule is the exception to it.”

On Punctuality

“Always appoint an hour at which you’ll see a man, and if he’s late a minute don’t bother with him. A fellow who can be late when his own interests are at stake is pretty sure to be when yours are.”

On Education

“A boy’s education should begin with today, deal a little with tomorrow and then go back to before yesterday. But when a fellow begins with the past, it’s apt to take him too long to catch up to the present.”

On Hiring

“It’s been my experience that when an office begins to look like a family tree, you’ll find worms tucked away snug and cheerful in most of the apples.”

On Humility

“You can’t do the biggest things in this world unless you handle men; and you can’t handle men if you’re not in sympathy with them; and sympathy begins in humility.”

On Truthfulness

“About the only way I know to kill a lie is to live the truth. When you credit is doubted, don’t bother to deny the rumors, but discount your bulls.”

On Dedication

“The real reason why the name of the boss doesn’t appear on a timecard is not because he’s a bigger man that anyone else, but because they shouldn’t be anyone around to take his time when he gets down and when he leaves.”

On Anger

“One of the first things a boss must lose is his temper—and it must stay lost. Noise isn’t authority and there’s no sense in ripping and roaring and cussing around the office when things don’t please you. For when a fellows’ given to that, his men secretly won’t care whether he’s pleased or not. The world is full of fellows who could take the energy which they put into useless cussing of their men and double their business with it.”

Like Carnegie, Vanderbilt, and Rockefeller, Graham’s brand of ambitious self-reliance was unforgiving. But, in what was an incredibly unforgiving time, it’s what people needed. Today, our world — whether you’re an entrepreneur or teacher — is just as unforgiving. So take heed and listen to Old Gorgon Graham.

This post originally ran on Forbes.com and ThoughtCatalog.com. Comments can be seen there.

December 27, 2013

24 Books You’ve Probably Never Heard Of But Will Change Your Life

Here’s the problem with reading the books that everyone else has read. It makes you more like everyone else. Checking off the various books from your high school curriculum, and then, perhaps the “100 Greatest Books Ever Written” is the educational equivalent of skating to where the puck is and not where it’s going.

Reading is about insight into the human experience, about understanding. What does following in the footsteps of everyone else get you? It gets you to exactly the same conclusions as everyone else.

Not to say that the books in our “canon” aren’t valuable, because they certainly are. It’s just that you have to remember for every Great Gatsby out there, there were 10 others written at the same time about the same thing that for whatever twist of cultural fate and cumulative advantage are mostly lost to us (one of the books on this list fits that definition to a T).

The Western world has been publishing books for some 3,000 years. Memoirs, histories, aphorisms, essays, treatises, tutorials, exposes, stories, epics–it’s all there. Humble yourself to think that our grasp of the lists of the “best” of these books will always miss more than it captures.

Which is why I put together the list of books below in their rough historical order. They are all great pieces of literature or learning and at the same time, mostly unknown. Sure, you might have heard of a few of them (in which case, consider yourself part of the minority) but far too many people haven’t. Put down your David Foster Wallace and pick up one of these. See what happens.

Cyropaedia (a more accessible translation can be found in Xenophon’s Cyrus The Great: The Arts of Leadership and War)

Xenophon, like Plato, was a student of Socrates. For whatever reason, his work is not nearly as famous, even though it is far more applicable. Unlike Plato, Xenophon studied people. His greatest book is about the latter, it’s the best biography written of Cyrus the Great (aka the father of human rights). There are so many great lessons in here and I wish more people would read it. Machiavelli learned them, as this book inspired The Prince.

The Moral Sayings of Publius Syrus: A Roman Slave by Publius Syrus

The best philosophy comes from people who were not “philosophers.” Syrus was a slave and his moral maxims are far better than perhaps the most famous book in this category, those of Duc de la Rochefoucauld. Some favorites: “The mightiest rivers are easy to cross at their source.” “Avarice is the source of its owns sorrows.” And of course, extra-applicable to this list, “Many receive advice, few profit by it.”

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (Gregory Hays translation, do not read the others, they suck)

Those familiar with my writing will not think this is an unknown book. But for far too many people it is. You can get a PhD in philosophy and not be forced to read this–and that’s a travesty. I imagine because it’s one of the few texts that wastes no time on pretension or explanations of the world. It simply tells you how to live a little better. Just wrap your head around this: At some point around 170 AD, the single most powerful man in the world sat down and wrote a private book of lessons and admonishments to himself for becoming a better, kinder and humbler person. And this text survives and you have access to it today.

The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari

Basically a friend and peer of Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Raphael Titian and all the other great minds of the Renaissance sat down in 1550 and wrote biographical sketches of the people he knew or had influenced him. Unless you have a degree in Art History it’s unlikely that anyone pushed this book at you and that’s a shame. Because these great men were not just artist, they were masters of the political and social worlds they lived in. There are so many great lessons about craft and psychology within this book. The best part? It was written by someone who actually knew what he was talking about, not some art snob or critic, but an actual artist and architect of equal stature to the people he was documenting.

The Man Without a Country by Edward E. Hale

Patriotism is not a concept that gets a lot of love today. But this essay/book makes you think a little. Released in 1863 during the height of the Civil War, the plot’s simple: an innocent man caught up in Aaron Burr’s treasonous conspiracy stands trial for his actions. When asked to address the judge, he bitterly remarks that he wishes to be done with the United States forever. So the judge grants his wish as a punishment–he’s sentenced to live the rest of his life in a cabin aboard ships in the US Navy’s foreign fleet, and no sailor is to ever mention the US to him again. He dies many years later, an old man like Rip Van Winkle, unsure of the changing world around him. For those with some understanding of historical, you’ll enjoy the meta-fiction of it, for those that haven’t it is still a very good look into early America.

12 Years A Slave by Solomon Northup

This one won’t stay unknown for long as Brad Pitt’s doing a movie about it but please don’t let that scare you away. If there is one book you read about slavery in America, read this one. It’s the real story of a born freedman in the North who, as a traveling musician, was brought out of his home state on false pretenses in order to be captured, kidnapped, and transported South to be sold as a slave. It’s fucking harrowing and written lucidly and articulately by the person who experienced it. For 12 years, he was a slave–and not some border-state slave, but a bayou slave in the deep South. He was cut off from his family and his freedom, and even among the slaves he was different. He couldn’t tell anyone he could read and write, he couldn’t even tell anyone that he was formerly free because they threatened to kill him if he did. This book is just as good as Frederick Douglass’ memoir and I think illustrates the horrors of slavery in a much more undeniable way.

Civil War Stories by Ambrose Bierce

Mark Twain, for all his bitterness and sarcasm, was just more fun for average people to read than Ambrose Bierce. But Bierce is the one who truly captured the Civil War–a terrible and awful conflict in which death and destruction and stupidity were far more prevalent than strategy or heroism. This book (half fiction and half memoir) contains the story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” which Kurt Vonnegut called the greatest short story ever written. Too many books about the Civil War are inaccessible, with their flanking movements and war vocabulary. This book is all people. Must read.

Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi by George Devol

The memoir of a professional gambler, fighter and criminal who rode the riverboats of the Mississippi and Red Rivers. It’s a true and vibrant snapshot of a period of American life that you can’t get anywhere else. Gun fights, brawls, cons–it’s all here. Fascinating, peculiar and very easy to read.

Hunger by Knut Hamsun

A dark and moving first-person narrative, about the conflicting drives for self-preservation and self-immolation inside all of us. Hunger is about a writer who is starving himself. He cannot write because he is starving and cannot eat because writing is how he makes his living. It’s a vicious cycle and the book is a first-person descent into it. Strangely modern for being published in 1890 and ultimately inspired a lot of great stream-of-consciousness writing since (but influence goes unacknowledged because Knut was a Nazi sympathizer).

Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son by George Horace Lorimer

This book is the preserved correspondence between Old Gorgon Graham, a self-made millionaire in Chicago, and his son who is coming of age and entering the family business. The letters date back to the 1890s but feel like they could have been written in any era. Honest. Genuine. Packed with good advice.

My Life and Battles by Jack Johnson

This is the lost and translated book that came out of a series of pieces Johnson–perhaps the greatest boxer who ever lived–wrote for a French newspaper in 1911. It’s not very long but it is full of really interesting strategies and anecdotes. You get the sense that he was an incredibly intelligent and sensitive man–clearly had a thirst for drama and attention. Who knows what place he would occupy in our culture and history had he not been taken down so thoroughly by racism and genuinely evil people? But despite all that, he was always smiling. As Jack London put it after Johnson’s most famous fight: “No one understands him, this man who smiles. Well, the story of the fight is the story of a smile. If ever a man won by nothing more fatiguing than a smile, Johnson won today.”

Company K by William March

Far and away the best book ever written about WWI. Better than All Quiet on the Western Front or Goodbye to All That or any of the other classics. But that’s the problem–WWI was awful, perhaps the most awful thing of the 21st century. And this book is forgotten precisely because it portrays the war and its pointlessness too realistically. We want to know, but we don’t really want to know.

Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis

I don’t think there was anyone in the 1920s who would have believed that this book would be completely forgotten. By all accounts, it was destined to be a classic critical novel of the American Dream. You can’t read anything about the ’20s and ’30s that doesn’t comment on Babbitt (sold 130,000 copies its first year, HL Mencken loved it, it won Lewis a Nobel Prize). Calling someone a “Babbitt” was considered an insult and the phrase became a constant topic of conversation in the media and literature. Yet, here we are 80-90 years later: you’ve probably never heard of the term or the book. Perhaps it’s because the biting satire of American suburban middle class life cuts deeper now than it did then. It doesn’t matter if the book is old, it’s still very funny and at its core, a critique of conformity and what Thoreau called the “life of quiet desperation.”

Asylum: An Alcoholic Takes the Cure by William Seabrook

In 1934, William Seabrook was one of the most famous journalists in the world. He was also an alcoholic. But there was no treatment for his disease. So he checked himself into an insane asylum. There, from the perspective of a travel writer, he described his own journey through this strange and foreign place. Today, you can’t read a page in the book without seeing him bump, unknowingly, into the basic principles of 12-step groups and then thwarted by well meaning doctors (like the one who decides he’s cured and can start drinking again). On a regular basis, he says things so clear, so self-aware that you’re stunned an addict could have written it–shocked that this book isn’t a classic American text. Yet all his books are out of print and hard to find. Two of my copies are first editions from 1931 and 1942. It breaks your heart to know that just a few years or decades later, his options (and outcome) would have been so very different (he eventually died of an opium overdose).

Ask the Dust by John Fante

This is the west coast’s Great Gatsby. Fante has benefited from some recognition–mostly thanks to Bukowski championing him in his later years–but because the book is about Los Angeles and not New York City, it is mostly forgotten. Better than Gatsby, it is a series. Bandini, the subject of the series, is a wonderful example of someone whose actual life is ruined by the fantasies in his head–every second he spends stuck up there is one he wastes and spoils in real life. He’s too caught up and delusional to see that his problems are his fault, that he’s vicious because he can’t live up to the impossible expectations they create, and that he could have everything he wants if he calmed down and lived in reality for a second. This is the series in order by my favorites: Ask the Dusk, Dreams from Bunker Hill, Wait Until Spring, Bandini and The Road to Los Angeles. (DO NOT watch the movie version of Ask to Dust, it is embarrassingly bad.)

Why Don’t We Learn from History? and Strategy by BH Liddell Hart

These are two very short books but will help you understand the topics more than thousands of pages on the same topic by countless other writers. In my view, Hart is unquestionably the best writer on military strategy and history. Better than von Clausewitz, that’s for sure (who for all the talk is basically useless unless you are planning on fighting Napoleon). His theories on the indirect approach is life changing, whether you’re struggling with a business or just office politics. I can’t say much more than read these books. It’s a must.

The Crack Up by F. Scott Fitzgerald

If you like Asylum, read The Crack Up, a book put together by Fitzgerald’s friend Edmund Wilson after his death. It is such an honest and self-aware compilation of someone hell-bent on their own destruction. At the same time, Fitzgerald’s notes and story ideas within the book make it undeniably clear what a genius he truly was. It’s a sad and moving but necessary read.

On the Rock: Twenty Five Years in Alcatraz by Alvin Karpis

John Dillinger was played by Johnny Depp. Most people know who he was–mostly because he died in a hail of bullets. But they forget that the other Public Enemy #1 at the time was Alvin Karpis and he didn’t die. In fact, he lived up until the 1980s. Just enough time to do a couple decades at Alcatraz with guys like Al Capone. During a temporary transfer to an alternate prison, Karpis met a young weirdo named Charlie Manson and taught him how to play guitar.

Death Be Not Proud by John Gunther

Written in 1949 by the famous journalist John Gunther about his death of his son–a genius–at 17 from a brain tumor, this book is deeply moving and profound. Every young person will be awed by this young boy who knows he will die too soon and struggles to do it with dignity and purpose. Midway through the book, Johnny writes what he calls the Unbeliever’s Prayer. It’s good enough to be from Epictetus or Montaigne–and he was fucking 16 when he wrote it. It’s reading the book for that alone.

The Harder They Fall by Budd Schulberg

Budd Schulberg’s (who wrote On the Waterfront) whole trilogy is amazing and each captures a different historical era. His first, What Makes Sammy Run? is Ari Gold before Ari Gold existed–purportedly based on Samuel Goldwyn (of MGM) and Daryl Zanuck. His next book, The Harder They Fall is about boxing and loosely based on the Primo Carnera scandal. His final, The Disenchanted is about Schulberg’s real experience being attached to write a screenplay with a dying F. Scott Fitzgerald. All you need to know about Schulberg’s writing is captured in this quote from his obituary: “It’s the writer’s responsibility to stand up against that power. The writers are really almost the only ones, except for very honest politicians, who can make any dent on that system. I tried to do that. And that’s affected me my whole life.”

Losing the War by Lee Sandlin

This is an essay, not a book, but if you have to read one thing about WWII, this is it. Sandlin is a master and the essay is free, read it.

The Measure of My Days by Florida Scott Maxwell

The daily notes of a strong but dying woman (born 1883, written in 1968) watching her life slowly leave her and wind to a close. The wisdom in this thing is amazing and the fact that most people have no idea exists–and basically wait until the end of their life to start thinking about all this is very sad to me. Also I love her generation–alive during the time of Wyatt Earp yet lived to see man land on the moon. What an insane period of history.

The Power Tactics of Jesus Christ and Other Essays by Jay Haley

The title essay in this book is peerless and amazing. The rest of the essays, which talk about Haley’s unusual approach to psychotherapy are also quite good. If you’ve gone to therapy, are thinking about going to therapy, or know someone going to therapy, this book is a must-read.

The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival by John Valliant

I’ll end with this book because it’s the most recent. The (true) story is simple: man in Siberia wounds tiger while hunting to feed his family. Tiger goes on killing spree while hunting the man down, and is stopped only when the Russian government dispatches a special SWAT team to track and kill it. This is probably the single best piece of nonfiction journalism I’ve ever read. I suppose it’s not totally unknown but I’m guessing you haven’t read it and that needs to change, now.

–

I’ve tried to capture most of the major eras and epochs above, from classical Greece to the Renaissance to the great wars of the 20th century. Yes, it is heavy on American history. But guess where most of the people reading this live?

Like I said, there are certain classic texts that we must read–books that have become cultural rites of passage. No one is saying you should skip your high school reading list. The problem is thinking that that’s enough. In order to work for “everyone,” those books had to be safe, they had to be accessible, they had to be provocative but not too provocative. There is a very understandable reason that we read All Quiet on the Western Front and not Company K. Or that we read Huckleberry Finn to understand slavery and not Solomon Northup’s real memoir.

Because the latter books are real. The others keep us comfortable, even when they make us think.

The next step is digging a little bit beneath the surface, leaving the road and exploring parallel or divergent paths. I hope some of these books do that for you. They certainly did for me.

This post originally ran on ThoughtCatalog.com. Comments can be seen there.

December 20, 2013

Best Book Recommendations of 2013

Everyone knows that reading is important, and most of us wish we did more of it. I understand that I am supremely lucky to have as much time to do it as I do. For that reason, at the end of each year, I try to narrow the hundreds of recommendations from my reading list down to just the very, very best. If you have to be selective with your time or money, these are the ones I promise are worth the time and investment. If you really like them and want more like it, the rest of the emails start with the Best Of 2011 and 2012 and stay tuned for January’s recommendations.

Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation by Tyler Cowen

This was the most important book I read this year. It’s the only one I framed a passage from to put on my wall. It was the only one I thought was so good I bought for multiple other people this year (it also inspired the one piece of writing I am most proud of this year). Cowen’s books have always been thought provoking, but this one changes how you see the future and help explain real pain points in our new economy–both good and bad. Although much of what Cowen proposes will be uncomfortable, he has a tone that borders on cheerful. I think that’s what makes this so convincing and so eye opening. A hollowing out is coming and you’ve got to prepare yourself (and our institutions) as best you can. To me, this book belongs along side other econo/social classics like Brave New War, Bowling Alone and The Black Swan. As a good extension of the themes in this book, I also recommend Plutocrats by Chrystia Freeland.

All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt by John Taliaferro

It’s hard for me to recommend just one great biography this year, so I won’t even try. I’ll just start with this biography of John Hay, which was my favorite–though there were many close seconds. John Hay started as a teenage legal assistant in the law office of Abraham Lincoln. He ended his career as the Secretary of State for William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. How nuts is that? You can basically understand the entire period of American history from the Civil War through WWI through one man who saw it all. Great biography of politics, the press, and American society. I also strongly recommend Eisenhower in War and Peace by Jean Edward Smith–I did not fully appreciate what a strategic and political genius Eisenhower was until this book. Jon Krakauer’s biography of Pat Tillman, Where Men Win Glory, was the most inspiring and moving book I read this year. Tom Reiss’s book The Black Count was impressive and a side of French history I never knew and never would have otherwise. You cannot go wrong with any of these biographies.

The Aneiad by Virgil (translated by Robert Fagles)

I made an effort to read some classical poets and playwrights this year. The Aneiad was far and away the most quotable, readable and memorable of all of them. There’s no other way to put: the story is AMAZING. Better than the Odyssey, better than Juvenal’s Satires. Inspiring, beautiful, exciting, and eminently readable, I loved this. I took more notes on it that I have on anything I’ve read in a long time. The story, for those of you who don’t know, is about the founding of Rome. Aeneas, a prince of Troy, escapes the city after the Trojan War and spends nearly a decade wandering, fighting, and trying to fulfill his destiny by making it to Italy. I definitely recommend that anyone trying to read this follow my tricks for reading books abve your level (that is, spoil the ending, read the intro, study Wikipedia and Amazon reviews, etc). I also enjoyed Euripides and Aeschylus this year and I hope you will too.

I can’t help myself. Some other honorable mentions:

Company K by William March (if you read one book about WWI, or one book of fiction about war, pick this one)

Eleven Rings: The Soul of Success by Phil Jackson (favorite business or leadership book in a long time)

Shadow Divers: The True Adventure of Two Americans Who Risked Everything to Solve One of the Last Mysteries of WWII by Robert Kurson (goddamn this guy can tell a story)

The River of Doubt and Destiny of the Republic by Candice Miller (these two unusual historical narratives about U.S presidents are shockingly good. I will read whatever else this woman writes)

–

For more great recommendations in 2014, sign up and stay tuned. If anyone has any gems to recommend, please send them my way. If you’re looking for marketing books, Trust Me I’m Lying came out in a revised and expanded edition this year and Growth Hacker Marketing is out now in ebook and audio and will be released in paperback in Sept 2014.

December 16, 2013

What is Scarce?

To put the question in the bluntest possible way, let’s say that machine intelligence helps us make a lot more things more cheaply, as indeed it is doing. Where will most of the benefits go? In accord with economic reasoning, they will go to that which is scarce.

In today’s global economy here is what is scarce:

1. Quality land and natural resources

2. Intellectual property, or good ideas about what should be produced.

3. Quality labor with unique skills

Here is what is not scarce these days:

1. Unskilled labor, as more countries join the global economy

2. Money in the bank or held in government securities, which you can think of as simple capital, not attached to any special ownership rights (we know there is a lot of it because it has been earning zero or negative real rates of return)

Tyler Cowen, Average is Over

This is now framed and on my wall.

December 2, 2013

How Dropping Out Of College Can Save Your Life

“One has to kill a few of one’s natural selves to let the rest grow — a very painful slaughter of innocents.” – Henry Sidwick.

You, the ambitious young person, how many of your natural selves have you identified yet? How many of them are suffocating? Are you prepared for the collateral damage that’s going to come along with letting the best version of you out?

My victims:

Ryan, college student 1 year from graduating with honors

Ryan, the Hollywood executive and wunderkind

Ryan, director of marketing for American Apparel

All dead before 25. May they rest in pieces.

I am a perpetual drop out, quitting, abandoning or changing paths just as many others in my position would be getting comfortable. By Sidwick’s terms, I guess I am a serial killer. This “slaughter” made room for the exponential growth of Ryan Holiday, published author. But he better not get comfortable either. Because he too may have to be killed one day. And that will be a good thing.

Because the future belongs to those who have the guts to pull the trigger. Who can drop out and fend for themselves. If you’re reading this site, you might already be contemplating a decision like that. I want to show you why it might be the right call for you and how to do it.

The Big Myth

“It wasn’t quite a choice, it was a realization. I was 28 and I had a job as a market researcher. One day I told my psychiatrist that what I really wanted to do was quit my job and just write poetry. And the psychiatrist said, ‘Why not?’ And I said, ‘What would the American Psychoanalytic Association say?’ And he said, ‘There’s no party line.’” – Allen Ginsberg

Let’s get the big myth out of the way. There’s not much dropping involved in dropping out of school. When I did it, I remember walking to the registrar’s office — I was so nervous. My parents had disowned me, I needed to move to a new city, the girl whose job I stole hated me. Why was I doing it? I’d just helped sign my first multi-platinum rock act and I wasn’t about to go back to the dorms and tolerate reading in the newspaper about other people doing my work. I was 20 years old.

I’m here to drop out of school, I announced to the registrar (like I was some presidential candidate who thinks he literally has to throw his hat into a ring). In fact, as my advisor informed me, that wasn’t exactly necessary. I could take a leave of absence for up to a year and possibly more, without even jeopardizing my scholarship. I braced for the same condescending, paternalistic lecture I’d gotten from my parents. It didn’t come. These people were happy for me. And if I submitted the right forms, I might even be able to get course credit for the work. How’s that for a party line?

So I took the plunge, and like many big risks, it turned out that dropping out of school was more manageable than I could have ever anticipated.

What I Wish I’d Known

I get a lot of emails from kids who are on the verge of dropping out. They always seem so scared. And I empathize with them. I know I was scared when I quit. Even billionaires, years removed from the decision that has now, in their case, been clearly vindicated, still speak of the hesitation they felt when they left school. Were they doing the right thing? What would happen? Were they throwing everything away?

It’s the scariest and most important decision most young entrepreneurs, writers, artists will ever make. So naturally, they take it very seriously. But doing that — taking it so seriously — almost wrecked me.

I remember pulling into a parking space one day a few months after dropping out, stressed and on the verge of a breakdown. Why am I killing myself over this?, I thought. It’s just life. Suddenly, a wave of calm washed over me. I was doing what young people are supposed to do: take risks. There is no need to stress over anything so seriously, let alone school (as someone told me later, he’d gotten sick when he was in college and missed 18 months of school. He’s 50 now and a year and half seems like two seconds). I’m not going to starve. I’m not going to die. There is nothing that can’t be undone. Just relax. Relax. And I did. And it worked.

If I’d realized it sooner, I could have avoided many needlessly sleepless nights.

I also wish someone had given me some more practical advice:

Try to have a few months money on hand. It makes you feel less pressure and gives you more power in negotiating situations.

Keep a strong network of friends — college friends especially. The unusualness of your situation is a warping pressure.

Keep connected to normal people so you can stay normal.

Take notes! I wish I’d written down my observations and lessons for myself the first time I dropped because it wasn’t my last time and I could prepared better for round II and III.

Why I Did It Again (and again)

When I dropped out of school, I was betting on myself. It was a good bet (one that surprised me, honestly). In less than 3 years, I’d worked as a Hollywood executive, researched for and promoted multiple NYT bestsellers, and was Director of Marketing for one of the most provocative companies on the planet. I had achieved more than I ever could have dreamed of — the scared, overwhelmed me of 19 could have never conceived of having done all that. (Which is why I killed that younger version of me). Yet, I knew it was time to drop out again. The six-figure job had to go. It was time for the next phase in my life. What I had, just like college had been, was holding me back.

That’s exactly what I did. I left and moved 2,000 miles away to write a book. It was wracking and risky and hard for everyone in my life to understand. But I was prepared this time. I knew what to expect. I’d saved my money, I built up my support system and I refused to take it too seriously. Whatever happened, I probably wouldn’t die.

…and I didn’t. In fact, within six months I’d sold the book to Penguin for several times my previous salary and was securely on my new path.

Welcome to the Future

I, and the many people who email me, seem to have a funny habit: We repeatedly leave and give up the things that most people work so hard to achieve. Good schools. Scholarships. Traditional jobs. Money. We don’t believe in sunk costs. If that sounds like you, then you’re probably a perpetual drop out too. Embrace it. I have.

I know that I will do it again and again in my life. Why? Because every time I do, things get better. The trial by fire works. It’s the future. The institutions we have built to prop us up seem mostly to hold creative and forward thinking people back. College is great, but it is slow and routine. Corporations can do great things, but fulfilling individuals is not one of them. Money is important but it can also be an addiction. Accomplishments like a degree or a job are not an end, they are means to an end. I’m so glad I learned that.

On your own path in life, remember the wise words of Napoleon and “Trade space for time.” (Or if you prefer the lyrics of Spoon “You will never back up an inch ever/that’s why you will not survive.”) Space is recoverable. The status of a college degree, the income from a job — recoverable. Time is not. This time you have now is it. You will not get it back. If you are stuck in a dorm room or wedged into a cubicle and what you are doing outside of those places is actually the greatest possible use of you, then it’s time to drop out.

Acknowledge, as Marcus Aurelius writes, the power inside you and learn to worship it sincerely. It may seem counter-intuitive that dropping out — quitting — is part of that, but it is. It’s faith in yourself. It’s about not needing a piece of paper or other people’s validation to know you have what it takes and are worth betting on. This is your life, I hope you take control and get everything you can out of it.

This post originally ran on Thought Catalog.com. Comments can be seen there. I also recommend this post 15 Reasons Why You Should Drop Out of College.

November 21, 2013

How To Travel — Some Contrarian Advice

Why are you traveling?

Because, you know, you don’t magically get a prize at the end of your life for having been to the most places. There is nothing inherently valuable in travel, no matter how hard the true believers try to convince us.

Seneca, the stoic philosopher, has a great line about the restlessness of those who seem compelled to travel. They go from resort to resort and climate to climate, he says. “They make one journey after another and change spectacle for spectacle. As Lucretius says, “Thus each man flees himself. But to what end if he does not escape himself? He pursues and dogs himself as his own most tedious companion. And so we must realize that our difficulty is not the fault of the places but of ourselves.”

It’s hard for me to see anything to envy in most people who travel. Because deep down that is what they are doing. Fleeing themselves and the lives they’ve created. Or worse, they’re telling themselves that they’re after self-discovery, exploration or perspective when really they are running towards distraction and self-indulgence.

Is that why you’re packing up your things and hitting the road?

Are you, as Emerson once put it, “bringing ruins to the ruins?”

The purpose of travel, like all important experiences, is to improve yourself and your life. It’s just as likely — in some cases more likely — that you will do that closer to home and not further.

So what I think about when I travel is that “why.” (Some example “whys” for me: research, to unplug, to go straight to the source of something that is important to me or I need to see in person, a job or a paying gig, to show something that’s important to me to someone who is important to me, etc etc) I don’t take it as self-evident that going to this place or that place is some accomplishment. There are just as many idiots living in Rome as there are at home.

And when you make this distinction most of the other travel advice falls away. The penny pinching and the optimization, the trying to squeeze as many landmarks into a single day, all that becomes pointless and you focus on what matters.

So what I am saying is that saving your money, plotting your time off work or school, diligently tracking your frequent flyer miles and taking a hostel tour of Europe or Asia on budget is the wrong way to think about it.

In the vein of my somewhat controversial advice for young people, I thought I’d give some of my thoughts not just on traveling but on how to do it right.

My Travel Rules and Criteria

[*] Instead of doing a TON of stuff. Pick one or two things, read all about those things and then actually spend time doing them. Research shows that you’ll enjoy an experience more if you’ve put effort and time into bringing it about. So I’d rather visit two or three sights that I’ve done my reading on and truly comprehend than I would seeing a ton of stuff that goes right in and out of my brain. (And never feel “obligated” to see the things everyone says you have to).

[*] Take long walks.

[*] What are you taking all these pictures for? Oh for the memories? So just look at it and remember it. Experience the present moment.

[*] Read books, lots of books. You’re finally in a place where no one can interrupt you or call you into meetings and since half the television stations will be in another language…use it as a chance to do a lot of reading.

[*] Eat healthy. Enjoy the cuisine for sure, but you’ll enjoy the place less if you feel like a fucking slob the whole time. (To put it another way, why are you eating pretzels on the airplane?)

[*] Try to avoid guidebooks, which are superficial at best and completely wrong at worst. I’ve had a lot more luck pulling up Wikipedia, and looking at the list of National (or World) Historical Register list for that city and swinging by a few of them. Better yet, I’ve found a lot cooler stuff in non-fiction books and literature that mentioned the cool stuff in passing. Then you google it and find out where it is.

[*] I like to go and stand on hallowed ground. It’s humbling and makes you a better person. Try it.

[*] Come up with a schedule that works for you. Me, I get up in the morning early and run. Then I work for a few hours. Then I roll lunch and activities into a 3-4 hour block where I am away from work and exploring the city I’m staying in. Then I come back, work, get caught up, relax and then eventually head out for a late dinner. In almost every time zone I’ve been in, this seems to be the ideal schedule to A) enjoy my life B) Not actually count as “taking time off.” No one notices I am missing. And it lets me extend trips without feeling stressed or needing to rush home.

[*] Don’t check luggage. If you’re bringing that much stuff with you, you’re doing something wrong.

[*] When you’re traveling to a new city, the first thing you should do when you get to the hotel is change into your workout clothes and go for a long run. You get to see the sights, get a sense of the layout and then you won’t waste an hour of your life in a lame hotel gym either.

[*] Never recline your seat on an airplane. Yes, it gives you more room — but ultimately at the expense of someone else. In economics, they call this an externality. It’s bad. Don’t do it.

[*] Stay in weird ass hotels. Sometimes they can suck but the story is usually worth it. A few favorites: A hotel that was actually a early 20th-century luxury train car, a castle in Germany, the room where Gram Parsons died in Palm Desert, a hotel in Arizona where John Dillinger was arrested, a hotel built by Wild Bill Hickok, etc etc.

[*] Add some work component to your travel if you can. Then you can write it all off on your taxes.

[*] Don’t waste time and space packing things you MIGHT need but could conceivably buy there. Remember, it costs money (time, energy, patience) to carry pointless things around. (Also, most hotels will give you razors, toothbrushes, toothpaste and other toiletries).

[*] Go see weird shit.

[*] Ignore the temptation to a) talk and tell everyone about your upcoming trip b) spend months and months planning. Just go. Get comfortable with travel being an ordinary experience in your life and you’ll do it more. Make it some enormous event and you’re liable to confuse getting on a plane as an accomplishment by itself.

[*] In terms of museums — I like Tyler Cowen’s trick about pretending you’re a thief who is casing the joint. It changes how you perceive and remember the art. Try it.

[*] Don’t upgrade your phone plan to international when you leave the country. Not because it saves money but because it’s a really good excuse to not use your cellphone for a while. (And if you need to call someone, try Google Voice. It’s free).

[*] You know there are lots of cool places inside the United States. The South is beautiful and chances are you haven’t seen most of it. There’s all sorts of weird history and ridiculous things that your teachers never told you about. Check it out, a lot of it is within a day or two drive.

In other words…

Travel should not be an escape. It should be part of your life, no better or no worse than the rest of your life. If you are so dissatisfied with what you do or where you live that you look forward to NOT being and spend weeks and months figuring out how to get a few days off from it, that should be a wake up call. There’s a big difference between wanting a change in scenery and some new experiences vs. needing to run away from a prison of your own making.

There is to me, a lot more to admire in someone who stayed put and challenged their perspectives and habits and lifestyle choices at home than there is to some first world Instagram addict who conflates meaning with checking off boxes on a bucket list.

So ask: Do you deserve this trip? Ask yourself that honestly. Am I actually in a place to get something out of this?

Over the years, I feel like I have mastered the art of something I wouldn’t call travel. I’d call it living my life in interesting places. When I can help it, I try to get paid to go to the places I go. What I don’t do is pine for the “opportunity” to go somewhere — because if I want it, I will make it happen.

These rules and tricks have helped make that possible. Maybe they’ll work for you too.

This post originally ran on ThoughtCatalog.com. Comments can be seen there. A different, expanded version, also ran on Fourhourworkweek.com.

November 15, 2013

So You Want To Write A Book? “Want” Is Not Nearly Enough

Painters like painting, the saying goes, writers like having written.

Are there exceptions to both sides of this rule? Of course. But anyone who has run the gauntlet and written a full-length book can tell you, it’s a grueling process.

You wake up for weeks, months or years on end, and at the end of each working day you are essentially no closer to finishing than you were when you started. It’s particularly discouraging work because progress feels so elusive. Not to mention that the pages you find yourself looking at rarely match what was in your head.

It’s for this reason that “wanting” to write a book is not enough. It’s not therapy. It’s not an “experience.” It’s hard fucking work.

People who get it into their heads that they “may” have a book idea in them are not the ones who finish books. No, you write the book you HAVE to write or you will likely not write it at all. “Have” can take many forms, not just an idea you feel driven to get out. You know, Steig Larsson wrote the Dragon Tattoo series to pay for his and his wife’s retirement.

If you honestly think you might be fine if you nixed the project and went on with your life as though the idea never occurred to you–then For The Love Of God, save yourself the anguish and do that. If, on the other hand, this idea keeps you up at night, it dominates your conversations and reading habits, if it feels like you’ll explode if you don’t get it all down, if your back is to the wall–then congratulations, it sounds like you’ve got a book in you.

Some tips:

-Writing a book is not sitting down in a flash of inspiration and letting genius flow out of you. Most of the hard work is done before you write–it’s the research and the outline and the idea that you’ve spent months refining and articulating in your head. You don’t get to skip this step.

-One of the best pieces of writing advice I ever got was to–before I started the process–articulate the idea in one sentence, one paragraph and one page. This crystallizes the idea for you and guides you on your way.

-Taleb wrote in Antifragile that every sentence in the book was a “derivation, an application or an interpretation of the short maxim” he opened with. THAT is why you want to get your thesis down and perfect. It makes the whole book easier.

that every sentence in the book was a “derivation, an application or an interpretation of the short maxim” he opened with. THAT is why you want to get your thesis down and perfect. It makes the whole book easier.

-Read The War of Art and Turning Pro

and Turning Pro .

.

-James Altucher wrote a very good post on “Publishing 3.0” over the weekend. Read that.

-Don’t think marketing is someone else’s job. It’s yours.

-Envision who you are writing this for. Like really picture them. Don’t go off in a cave and do this solely for yourself.

-Do you know how a laptop feels when you think you’ve closed it but come back and find out that it’s actually never shut down? That’s how your brain feels writing a book. You’re never properly shut down and you overheat.

-Expect your friends to let you down. They all say they are going to give notes but few actually will (and a lot of those notes will suck).

-Work with professionals. If you’re self-publishing, that means hiring them out of your own pocket.

-When you hit “writer’s block” start talking the ideas through to someone you trust. As Seth Godin observed, “no one ever gets talker’s block.”

-Plan all the way to the end, as Robert Greene put it. I am talking about what the table of contents and the bibliography are going to look like and what font you’re going to go with. Figure out what the final end product must look like–those are your decisions to make. Or someone else will and they’ll make the wrong choice.

-Good news: You used to have to worry that no one would ever see this thing you put your whole soul into. (It’s such a scary thought that John Kennedy Toole killed himself over it.) Well, you don’t have to worry about publishers rejecting you anymore. Obviously, it’d be better to have a major house backing you, but remember, you can always self-publish. So fuck ‘em if they reject you.

-Have a physical activity you can do. That will be the therapy. Trust me, you’ll want the ability to put the book down and go exert yourself. Plus the activity will keep you in the moment and many of your best ideas will pop into your head there. (Personally, running and swimming work for me.)

-Have a model in mind, even if you’re doing something totally new (read The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry if you’re interested in this psychologically). Thucydides had Herodotus, Gibbon had Thucydides. Shelby Foote had Gibbon. Everyone has a master to learn from.

if you’re interested in this psychologically). Thucydides had Herodotus, Gibbon had Thucydides. Shelby Foote had Gibbon. Everyone has a master to learn from.

-Plan for it to take longer than expected. Way longer.

-As Fitzgerald wrote in The Crack Up , avoid the temptation of “going to somewhere to write.” You can write anywhere–the idea that you need to travel or go away to put words down is often just a lie or a procrastination. (That being said, for my first two books, I moved thousands of miles away to places I didn’t know anyway. This can work.)

, avoid the temptation of “going to somewhere to write.” You can write anywhere–the idea that you need to travel or go away to put words down is often just a lie or a procrastination. (That being said, for my first two books, I moved thousands of miles away to places I didn’t know anyway. This can work.)

-You’ll “lose your temper as a refuge from despair.”

-Don’t talk about the book (as much as you can help it). Nothing is more seductive (and destructive) than going around telling people that you’re “writing a book.” Because most non-writers (that is, the people in your life) will give you credit for having finished already right then and there. And you’ll lose a powerful motivation to finish. Why keep going if you’ve already given yourself the sense of accomplishment and achievement? That’s the question the Resistance will ask you at your weakest moment and you might lose it all because of it.

-“Don’t ever write anything you don’t like yourself and if you do like it, don’t take anyone’s advice about changing it. They just don’t know.” – Raymond Chandler

–

Everyone has their own tricks and rules and they’re going to be a little different than mine. I’m not saying every single one of the tips above will work.

But the idea around which they are based is not a controversial one. Books are hard. As in one of the hardest things you will likely ever do. If you’re only marginally attached to your idea or the notion of writing a book, you will not survive the process. “Wanting” is not enough. Write the book you HAVE to write, and if you’re not at that point yet, wait, because the imperative will come eventually.

The good news is that everyone who has been there understands. They remember and empathize with Thomas Mann’s line, “A writer is someone to whom writing does not come easily.” You can ask them for advice. They will be, in my experience, incredibly understanding and approachable.

Good luck. And don’t let this kick your ass.

This post originally ran on ThoughtCatalog.com. Comments can be seen there.

November 4, 2013

How I Did Research For 3 New York Times Bestselling Authors (In My Spare Time)

I’m going to talk about research. No, research is not very fun, and it’s never glamorous, but it matters. A lot.

If you want to be able to make compelling case for something — whether it’s in a book, on a blog, or in a multi-million dollar VC pitch — you need stories that frame your arguments, rich anecdotes to compliment tangible examples, and impressive data so you can empirically crush counter arguments.

But good research doesn’t just magically appear. Stories, anecdotes and data have to be found before you can use them.

You have to hunt them down like a shark, chasing the scent of blood across the vast ocean of information. The bad news is that this is an unenviable task … but the good news is that it’s not impossible.

It’s not even that hard … once you learn what you’re doing — and I’m going to teach you those skills.

By the time I was 21, my research had been used by #1 New York Times Bestselling authors like Robert Greene, Tim Ferriss, and Tucker Max (all of whom helped me immensely and improve as I went along). Was I a slave to study? Did I have to become a library hermit to accomplish this? No, I did it all in my spare time —on the side, often with just a few hours of work a week.

Here’s how I did it…

Step 1: Prepare long before gameday

In The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb proposes a test.

Someone walks into your house and sees your many books on your many bookshelves. Have you really read all these? they ask. This person does not understand knowledge. A good library is comprised in large part by books you haven’t read, making it something you can turn to when you don’t know something. He calls it: the Anti-Library.

I remember once in college, the pride I felt about being able to write an entire research paper with stuff from my own anti-library. We all have books and papers that we haven’t read yet. Instead of feeling guilty, you should see them as an opportunity: know they’re available to you if you ever need them.

When I met Robert Greene and he asked me to become his research assistant, the only thing that changed was that I started getting paid.

I’d already marked and organized hundreds of books with interesting leads and material and many other relevant books I had yet to get to. I had a Delicious account with countless links to articles and pages that might “someday” be of use. I’d been practicing on my own by researching examples of some of the famous laws in his books after they’d been published — in case I ever got called up to the big leagues. What Robert did was show me how to organize and channel this energy in the right direction.

This is the mark you must aim for as a researcher, to not only have enough material — and to know where the rest of what you haven’t read will be located — on hand to do your work. You must build a library and an anti-library now … before you have an emergency presentation or a shot at a popular guest post.

Google is great, don’t get me wrong, but you’re screwed if you haven’t prepared beforehand.

Step 2: Learn to search (Google) like a pro

How do you find a needle in haystack? Get rid of the extra hay.

What seems like an overwhelming mass of information is often mostly noise. Eliminate it. Take a tip I learned from Tim Ferriss. When he was researching for the secrets behind health and diet, he used a few specific hacks to drastically reduce the search area he needed to cover.

For example, if he was looking for a high level athlete, he’d go on Wikipedia and find the world’s first and second-best athletes in that sport from a decade ago. Why? It meant there would be plenty of available material and unlike athletes currently on top of the world, these would be willing and available to talk.

He’d search Google with phrases like “[My closest city] [sport] ['Olympian' or 'world champion' or 'world record']” A search for “San Francisco bobsled Olympian” might get him a recently retired team doctor — the perfect lead to start with.

In other words, don’t look for just any needle in your haystack of choice. Look for the right needle.

Me, I like to look for phrases, in order to find unlikely subjects.

Let’s say you were looking to talk about a great fighter pilot — not some legendary WWII figure but someone current, relevant to today. You’re not in the military, how are you supposed to find this guy? I like to think about it from the perspective of the writers who came before me, how would they have described the person I’m trying to find? What superlatives would they use? Probably stuff like “The Last Ace,” “Living Aces,” or “America’s greatest living airman.”

You’re looking for words that will appear in a profile or even in the headline of an article about the person you are looking to find, so that you can troll LexisNexis, Google News Archive, and even Google itself to find that person.

The phrase “The Last Ace,” as it turns out, happens to be the title of a fantastic article in The Atlantic by Mark Bowden and now you’ve got your fighter pilot (and one of the main subjects of Robert Greene’s new book).

Step 3: Go down the rabbit hole (embrace serendipity)

A couple years ago, I was contributing to a project and needed to make an analogy to mountain climbing — about a climber’s feel for the mountain.

Well, I don’t know anything about rock climbing. But I did remember seeing a commercial once with the founder of Patagonia talking about how he loved it. I found my example but decided to take a chance with something more: buried in the founder’s Wikipedia page was a mention of his friend, a named Fred Beckey. Who is he? I had no idea, but I started reading about him and it turns out he was awesome. And he led me to another climber, who ended up supplying me with the perfect quote.

You have to embrace the accidental.

In researching my first book, which was sold to Penguin for a major, six-figure advance, I read nearly everything I could find about the history and ecology of media. But that’s not where I found my best material.

In a book about media (and my own personal experiences) I somehow made my strongest citations from Ender’s Game, The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler, All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren, Status Anxiety by Alain de Botton, and a handful of other books.

Directly, these books had nothing to do with what I was writing about, but because my mind was primed to see connections, I found them in the most unusual places.

I can’t tell you how many leads I’ve tracked down from random Wikipedia citations. Explore what you’re curious about and know, and let it lead you to what you don’t.

One of my rules as a reader is to read one book mentioned in or cited in every book that I read. It not only solves the problem of ‘what to read next’ but it sends you on a journey down the rabbit hole.

Step 4: When in doubt, turn to the classics

Remember, there is nothing new under the sun. And if we’re all just saying the same things with new words, what quote is going to have more authority: one from Tacitus or some flavor-of-the-month blogger?

For me, when I research, the blank icon of an out of print book on Amazon is a clue not just that I have found something unlikely to have been overused by others, but something I can mold to my purposes (plus they only cost like $.01!).

There’s a character in Murakami’s Norwegian Wood who wouldn’t read books unless the author had been dead for 30 years. That’s a little ridiculous, but it’s a start.

The Classics are “classic” for a reason. They’ve survived the test of time. Consider it the survivorship bias put to your advantage. Von Clausewitz once said that military historians love to cite Greek and Roman history because, as the oldest and most obscure, it is the easiest to manipulate. I don’t see that as an admonishment, I see it as a helpful suggestion from a master of persuasion.

Step 5: Keep a commonplace book

While researching an article I wrote for Tim Ferriss’ blog, I discovered (and subsequently borrowed) a tool used by the famous essayist and experimenter Montaigne.

Montaigne kept what he called a “common place book” — a book of quotes, sentences, metaphors and miscellany that he could use at a moment’s notice. I keep a more modern — but still analog — version of this book. I write everything down on 4×6 note cards, which I file in boxes. (You could do this digitally, I suppose, but the physical arrangement — being able to lay them out on a desk — is critical to my work). I picked up this system from Robert Greene, who also used it for his books.

This means marking everything you think is interesting, transcribing it and organizing it. As a researcher, you’re as rich as your database. Not only in being able to pull something out at a moment’s notice, but that that something gives you a starting point with which to make powerful connections. As cards about the same theme begin to accumulate, you’ll know you’re onto a big or important idea.

For me, I have two book ideas percolating, each about 200 index cards full. Will something come of them? I don’t know, it depends on how many more connections I make, how many random coincidences align to bring those connections to light.

All I know is that my last book (close to 1,000 cards) came together this way.

Why research?

Maybe you’re not a writer or a blogger. But, we’ve all found ourselves in a position where we need to convince people to do things they are not inclined to do.

When force is not an option, what do we do? We use the next best thing: persuasion. And when it comes to persuasion stories are important.

Anecdotes are persuasive.

Data dominates.

These things do not appear from thin air, or fall in our lap. We must search for them like a professional.

But as I’ve shown, this doesn’t need to consume your life. It can be done efficiently and expertly by focusing our efforts on the right levers. With preparation, we lengthen our runway. By eliminating noise, we drastically reduce the size of the search. With serendipity, we set ourselves up to be lucky and by relying on the classics, we give our arguments more weight. And by organizing and collecting this information properly, it is there wherever (and whenever) we need it.

Even if our research isn’t used today — or even tomorrow — it can still have immense value for us throughout our lives. I’ll leave you with Seneca’s persuasive case for noting, repeating and memorizing material …

My advice is really this: what we hear the philosophers saying and what we find in their writings should be applied in our pursuit of the happy life. We should hunt out the helpful pieces of teaching and the spirited and noble-minded sayings which are capable of immediate practical application — not far-fetched or archaic expressions or extravagant metaphors and figures of speech — and learn them so well that words become works.

This post originally ran on ThoughtCatalog.com and Copyblogger. Comments can be seen there.