Piotr Naskrecki's Blog, page 5

December 19, 2013

Who was Per Brinck?

Brinckiella elegans – a beautiful species from Western Cape Province of South Africa. Females of all species in this genus, and males in at least one, are completely wingless. This is rare among katydids and I still don’t have a good explanation for this loss of the ability to both fly and produce courtship calls.

Taxonomists, myself included, are often asked how we choose names for the organisms we discover and describe. Some are surprised to learn that species are often named after people, but that is also inappropriate to name species after yourself (albeit I know of one such case*). Naming species and genera after people is in fact so common that taxonomists rarely pause to ponder who Welwitsch (Welwitschia), Scudder (Scudderia), or Wahlberg (Clonia wahlbergi, Aquila wahlbergi, Arthroleptis wahlbergi and more) might be or have been.

As I am sitting in front of my miscroscope, preparing a description of yet another African katydid of the genus Brinckiella, I realize that it never occurred to me to find out who Brinck was, the person after whom the genus was named in 1955. All I know is that he was one of the editors of a monumental, 15-tome treatment of the results of an expedition across southern Africa in 1950-1951. It was during this expedition that a single, tiny green katydid was collected, later to be named after its collector Brinckiella viridis by a French entomologist Lucien Chopard.

For some reason I assumed that Brinck, whoever he was, must be long dead – somebody who published a 15-tome treatise in the early 1950’s would have to be at least 120 by now, right? Well, yes and no. Professor Per Brinck has indeed died. But he only died two months ago, at the age of 94 in his home in Oland, Sweden. He was that country’s leading ecologist, one of the founders of the Nordic Foundation Oikos and editor of the journal Oikos. He was also a an expert on whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae) and dragonflies. He might have liked to receive a copy of my revision of the genus Brinckiella, which I published with my friend Corey Bazelet a few years ago. Alas, I never thought of it and now it’s too late.

An so, next time you run across an insect’s weird name that sounds like it might have been named after somebody, make an effort to find out who that person was. That – let’s pick a random patronym – may bear the name of somebody very interesting, you just never know.

B. karooensis can be found only on karoo vegetation along the western coast of South Africa.

*) Wall’s krait (Bungarus walli), a highly venomous snake related to cobras, was named by Frank Wall, a British officer and a medical doctor working in India in the early 1900s. His paper is a delight to read, here is an excerpt where he justifies naming the species after himself:

“[...]At the Club in the afternoon I was pursued by an urchin who produced another specimen which, to my satisfaction, I found to exactly accord with the morning one, and after getting home while dressing for dinner the same boy brought me a third, identical in the peculiarities first noted. Thus in one day I acquired three specimens of a snake hitherto unknown ! I may mention that the day’s bag exceeded 100 snakes of all kinds ! These three Kraits were all small. Since this I have obtained 8 of the same species, and though I believe it a breach of ethics for any naturalist to call a species after himself, the fact that this is the first new snake I have discovered in 11.5 years’ hard collecting, may be pleaded as sufficient excuse for commemorating the event and attaching my own name to it.”

Wall, F. 1907. A new krait from Oudh (Bungarus walli). J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 17:155-157.

Filed under: Katydids

November 25, 2013

Hugewings

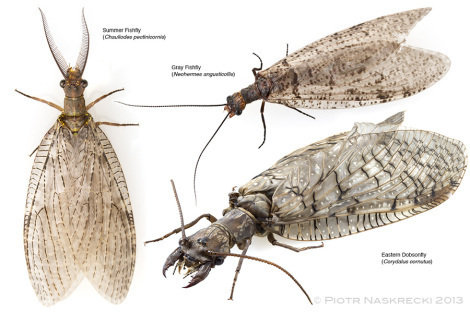

The enormous mandibles of a male dobsonfly (Corydalus) look like formidable weapons, but they are not. The males use them only in ritualized combat with other males, and are too weak to use them to pinch or hurt anybody.

As somebody who grew up in Europe I was really hoping that enrolling in a graduate school in the US would give me a chance to see many organisms that are rare or completely absent from the Old Continent. And, sure enough, as soon as I arrived in New England I almost got into a car accident after spotting my first Virginia possum, I giggled like a little girl at the sight of Black vultures feasting on a roadkill (probably a possum), and almost had a heart attack from the excitement of finding my first horseshoe crab on a beach in Connecticut. But nothing could prepare me for what one evening came to the light of the house that I shared with my then girlfriend. It was a creature so spectacular and unlike anything I had ever seen that it took me a while to even put it in a broad taxonomic context. “It’s a megalopteran!”, I finally managed to exhale. “Oh yeah, a dobsonfly”, said Kristin, “They are pretty neat.”

Female dobsonfly in her natural habitat along a stream in Tapanti National Park in Costa Rica.

That was my first introduction to the genus Corydalus, a massive creature that fully deserves to be a member of an insect order christened Megaloptera, or Hugewings (I just made this name up, but I think it’s fitting; as far as I know Megaloptera do not have a single-word common name despite being a well-recognized monophyletic lineage). They easily attain a wingspan of 140 mm (5.5″) and in flight are more akin to bats than insects. The dobsonfly that came to our light was a male and thus carried enormous, tusk-like mandibles that gave him a menacing look.

One of the few colorful members of the order Megaloptera, a Costa Rican dobsonfly Chloronia sp.

But, like so many seemingly dangerous invertebrates, a male dobsonfly could not hurt anybody even if he really tried. The gigantic mandibles are for show only, and the animal barely has enough muscle power to open and close them; actually biting is completely out of the question. Males use these ridiculous implements in largely ritualized combat with their rivals, a slower, weaker version of the jostling display seen in stag beetles. But be careful with dobsonfly females – while the males carry a pair of chopsticks, these have a pair of powerful wire cutters that can easily draw blood from careless fingers. Dobsonflies don’t live long as adults and, other than drinking water or an occasional visit to a flower to sip some nectar, don’t feed, and die within a few days.

A female dobsonfly taking off from a leaf at night in Tapanti National Park in Costa Rica.

The genus Corydalus is represented by 34 species, found mostly in the tropical regions of the Americas, and only the Eastern dobsonfly (C. cornutus) reaches as far North as Canada, while two additional species can be found in the southernmost parts of the US. The mandibles are enlarged in males of most species in this and in a closely related genus Acanthacorydalis from E Asia, although in Costa Rica I once caught a male of another dobsonfly with exaggerated sexual traits, Platyneuromus soror. His head carried two strange plates that reminded me of the facial lobes seen in an old male orangutan. Why they have them is unknown as they do not appear to use them in any way during courtship or mating.

The function of the large lobes on the head of Central American dobsonfly Platyneuromus soror is a complete mystery.

The larvae of dobsonflies are aquatic and are well known to fishermen as hellgrammites (or helgies) – large, wiggly insects that make excellent bait for bass and trout. They are predators of other aquatic insects, such as caddis flies. Interestingly, while most species prefer large, well-oxygenated bodies of water (and thus make good indicator species of water quality), larvae of some hugewing species are capable of developing in such unusual habitats as water accumulated in tree holes or the digestive liquid at the bottom of pitcher plants. Those species that live in seasonal bodies of water are capable of aestivation, burying themselves is mud cocoons to await the return of water (very much like the lungfish). Interestingly, dried larvae of Megaloptera are used in Japanese traditional medicine to treat emotional problems in children, they are also consumed as a snack Zazamushi (not very tasty, according to my friend Kenji).

Hugewings give the impression of being ancient and primordial, and for good reason. They date back to the Permian, and are probably direct descendants of some of the earliest holometabolan insect (insects with the complete metamorphosis). They used to be lumped with the Neuroptera (netwings), but there is good evidence for their status as a monophyletic sister group to the Neuroptera.

Three species of hugewings common in New England.

Filed under: Costa Rica, Megaloptera, New England

November 15, 2013

Mozambique Diary: Poetic justice

The Cape centipede-eater (Aparallactus capensis) from Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique

If we lived in an ideal world, right about now I would have been putting on my headlamp to begin stalking katydids in the luxuriantly green savannas of Gorongosa National Park. But, alas, we don’t. For reasons beyond my control I had to postpone a trip to Mozambique, although I hope to be able to get there within the next couple of months or so, and witness the park in its full, rainy season splendor.

When I was in Gorongosa in May, conducting a biodiversity survey of the Cheringoma Plateau, I was introduced by our intrepid herpetologists, MO Roedel and Harith Farooq, to an interesting little snake. The Cape centipede-eater (Aparallactus capensis), feeds, as the name suggests, exclusively on centipedes. These arthropods are not the friendliest of creatures, in fact I have a very healthy dose of respect for these powerful, blindingly fast predators. All centipedes are venomous and those large enough to be able to puncture human skin can deliver nasty, nasty bites. Their body shape, however, seems to make them ideal prey for snakes – they are long and thin, and a single centipede would nicely fill a snake of comparable size.

Aparallactus hunts by grabbing the victim in the middle of the body and slowly working its way towards the head, eventually swallowing the centipede head-first. The scales on this snake’s body are particularly hard, making it difficult for the centipede to sink its fangs (forcipules) into the reptile. At the same time the snake’s venom quickly subdues and kills the prey. Aparallactus belongs to a lineage of snakes known as side-stabbing snakes (Atractaspididae), which includes several deadly venomous species. But despite being powerfully venomous, centipede-eaters are not dangerous to humans as their short fangs are located in the back of the jaw and cannot reach the surface of our skin; one of the members of the genus, Aparallactus modestus, is even entirely fangless and feeds mostly on earthworms.

I have read that Aparallactus are immune to venom of their centipede prey, but the same cannot be said of other snakes found in Gorongosa. One rainy night on Mt. Gorongosa I ran across a scene that reinforced my high opinion of these multi-legged invertebrates: a large centipede was efficiently chomping to bits a House snake (Lamprophis capensis). If this is not the best example of poetic justice then I don’t know what is.

Centipede (Ethmostigmus sp.) devouring a House snake (Lamprophis capensis)

Filed under: Chilopoda, Gorongosa, Mozambique, Reptiles

November 5, 2013

The amazing Glass katydid

A young nymph of Glass katydid (Phlugis teres) from Suriname sitting on the tip of my finger.

Once again things have been slow on my blog as I am trying to finish a million little things before my upcoming departure for Mozambique. I will be arriving there at the beginning of the rainy season, which means tons of insects and other invertebrates, a multitude of frogs, and hopefully some great new stories for this blog.

One of the animals that I hope to see there is a pretty, yet unnamed katydid from Mt. Gorongosa, which I first found last year in the mid-elevation rainforest on the mountain slopes. I am now working on its formal description and will post its photos as soon as the paper is out. In the meantime I thought I would present one of its close relatives, the amazing Glass katydid from Central and South America, a member of the genus Phlugis (Listroscelidinae).

As they age, Glass katydids begin to lose their transparency, and older nymphs and aduls acquire pale green coloration.

I coined the name Glasss katydid after seeing for the first time young nymphs of Phlugis teres, a species found in Suriname, who display remarkable, nearly complete transparency of their bodies. These minute insects truly look as if they were made of glass and, peering closely, it is possible to see most of their internal organs, including the entire tracheal system. Unfortunately, these katydids lose most of the transparency as they get older, and eventually acquire pale green coloration, occasionally marked with brown accents.

It would seem that something so seemingly fragile cannot feed on anything other than dew and rose petals, but in fact Glass katydids are agile, powerful predators. Unlike most of neotropical katydids, the genus Phlugis includes many diurnal species that use their excellent vision to find prey, and their hunting technique is very clever. Glass katydids are sit-and-wait predators who spend most of the day sitting upside down on the underside of large, thin leaves, usually at the edge of the rainforest or in open, shrubby habitats. They prefer leaves that are fully exposed to the sun so that any insect landing on its upper surface will cast a dark, sharply defined shadow. And that shadow is what Glass katydids are waiting for – it tells them whether the insect is a hard beetle (not good) or a soft fly (excellent), and if the insect looks like a good meal they launch themselves from under the leaf and onto its surface, and capture the victim with their long, very spiny legs in a blink of an eye.

In addition to being some of the most sophisticated and fastest orthopteran predators, Glass katydids are famous for the sound they produce – their call exceeds the frequency of 55 kHz, which is about three times the frequency a human ear is capable of hearing. A closely related genus Archnoscelis holds the record of producing the highest frequency call among all invertebrates – a whopping 129 kHz, twice the frequency of echolocation of most bats, and about 10 times more than the hearing ability of most adult humans. Another reminder that the ability to look cool and do amazing things seems to be inversely correlated with the body size.

Their huge eyes are a good indication of Glass katydids’ mode of hunting – they are diurnal sit-and-wait predators of small flies and other soft insects. This newly discovered, yet unnamed species of Phlugis from Costa Rica hunts small flying insects along the edges of mid-elevation rainforest.

Filed under: Behavior, Costa Rica, Katydids

October 22, 2013

Bog killers

Sphagnum ground cricket (Neonemobius palustris) from Ponakpoag Bog, MA.

The one thing about plants that we take for granted is that they cannot really hurt you. Sure, some are full of toxic compounds and can be deadly poisonous if ingested. Others are covered with nasty spines or irritating hairs, and a tree can fall on your head during windy weather and crack your skull. But we feel pretty secure in the fact that no plant can hunt and eat you. Things would be very different, however, if we weren’t some of the largest animals on the planet.

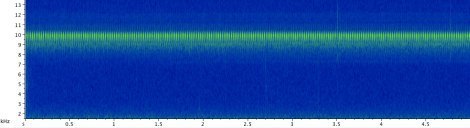

The call of the Sphagnum ground cricket is a soft, high-pitched trill, which is easy to miss unless your are looking for it. Click here to hear the recording of the call at the natural speed, followed by a fragment slowed down 5 times.

I was having these thoughts last Sunday when I went looking for another singing insect, the minute Sphagnum ground cricket (Neonemobius palustris), one of a few species of New England acoustic orthopterans that I had never managed to get a recording of. I decided to try looking for it at Ponkapoag Bog in the Blue Hills Reservation, about 10 miles S of Boston. Almost immediately after stepping on the wooden planks that run through the soggy Sphagnum bog I started hearing the characteristic, high-pitched tinkling of those small crickets. But it took me a while to find one, and I only managed to do so after a considerable amount of crawling on all fours, waving a shotgun microphone to pinpoint the source of the sound. Eventually I located one individual in a sunny spot, deep in a clump of red and green moss. As I was recording his song, I also marveled at the idyllic setting of this species’ home. “What a great place to live for an insect”, I thought, “no predaceous ground beetles, no centipedes, water and food plentiful.” But then I heard behind me somebody say “Look honey, bladderworts! They catch and eat aquatic insects.” Right, I forgot about the killer plants.

Looking like a hungry snake, the gaping mouth of the pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) invites unsuspecting insects to their death.

Bogs are strange communities, not quite aquatic, not quite solid ground. The constant presence of low levels of water leaches nutrients from the soil, making the habitat extremely poor in minerals, particularly nitrogen. Some plants can fix atmospheric nitrogen thanks to a symbiotic relationship with cyanobacteria in their root system, but most need to find another way, and some do so by becoming carnivorous. I looked around and just a couple of feet from where my cricket was happily singing sat a gaping mouth of the pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea). The plant was half hidden in the moss, the lower lip of its pitcher conveniently at ground level, its entrance inviting to any cricket looking for a hiding place or something to eat. The bottom of the pitcher was dark with half-digested bodies of insects, a few still floating on the surface. The lip’s surface was covered with backward-pointing spines, making it easy for an insect to walk in, but virtually impossible to leave. It was as if you walked into your local grocery store, only to realize that you are in the Little Shop of Horrors.

Unlucky insects and arachnids being digested in the pitcher.

In addition to bladderworts and pitcher plants, Ponkapoag Bog is a great place to see honeydews (Drosera rotundifolia). Unlike pitcher plants, which lure and drown insects, sundews actively grab them with their sticky, glandular tentacles that cover their modified leaves. They mostly catch small midges and gnats, but I saw one plant successfully capture a pretty big damselfly using two of its leaves at once. Of course the insect must first touch the plant, but once it does, it is pretty much doomed as the leaves curl and immediately start digesting the prey. I often complain that our huge body size prevents humans from appreciating most of the richness and beauty of the natural world, but carnivorous plants are another reason to think that maybe it is not such a bad thing after all.

Purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) from Ponkapoag Bog, MA. The color of the plant is an indirect indication of the availability of nitrogen – the greener the plant, the more nitrogen is present in its environment. A recent study demonstrates that pollution by synthetic fertilizer makes carnivorous plants less interested in insects and more reliant on nitrogen dissolved in the water.

The pitchers of S. purpurea are its modified leaves, not flowers. Its true and remarkably beautiful flowers appear in the late spring and, unlike the pitchers, are insect-friendly.

Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) from Ponkapoag Bog, MA with two half-digested midges.

Even an insect as big as a damselfly can fall victim to a sundew.

Filed under: Crickets, New England, Orthoptera, Plants

October 14, 2013

The chorus grows

A singing male Handsome trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus)

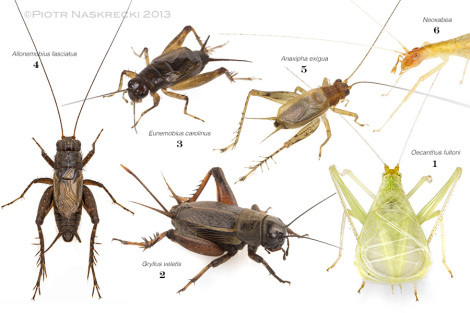

On this sunny Columbus Day I stayed at home, which allowed me to discover another beautiful musician in my garden’s chorus, the Handsome Trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus) (also known as the Red-headed Bush Cricket). I already wrote about this species, but I never suspected that I would find one of my favorite North American orthopterans in my very own garden. Around noon I noticed a cricket song that I had never heard around my house before. Armed with a directional microphone and a net I followed the twitter, and found him singing from the upper surface of a large leaf, about 6 feet above the ground. This finding brings the number of crickets found around my house to 11:

Handsome trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus)

Say’s trig (Anaxipha exigua)

Carolina ground cricket (Eunemobius carolinus)

Allard’s ground cricket (Allonemobius allardi)

Striped ground cricket (Allonemobius fasciatus)

Two-spotted tree cricket (Neoxabea bipunctata)

Snowy tree cricket (Oecanthus fultoni)

Spring field cricket (Gryllus veletis)

Fall field cricket (Gryllus pennsylvanicus)

Eastern ant cricket (Myrmecophilus pergandei)

House cricket (Acheta domesticus) (introduced)

Sonogram of the Handsome trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus); click here to listen to the recording.

A male Handsome trig (Phyllopalpus pulchellus)

Filed under: Behavior, Crickets, Orthoptera

October 10, 2013

Music in my head

Male Carolina ground crickets (Eunemobius carolinus) are the hardiest of all my garden’s musicians, and may continue to woo females with their song well into late November.

I have always wanted to be a musician. Not that I have any particular musical talents (and never learned to read music), but my fascination with sound was definitely one of the reasons for becoming an expert in the taxonomy of orthopteroid insects, nature’s preeminent musicians. Few things are more pleasant to me than sitting on the deck of our house near Boston on a warm summer evening – a high frequency sound recorder in one hand, a glass of gin & tonic in the other – and getting lost in the hypnotic chorus of about a dozen species of katydids and crickets that share our garden with us. (The best part of this activity is that I can call it “data collecting”.) Now that the summer is sadly over, all I have is the memory of beautiful garden soundscapes, and a bunch of recordings. There are still some strugglers out there – just the other night I found a Sword-bearing conehead (Neoconcephalus ensiger) singing on the lawn in front of our house – but let’s face it, it will be very quiet very soon. And thus I thought that this might be a good time to put all of this year’s recordings together into one composite soundscape, and relive the aural painting that I am privileged to experience every summer.

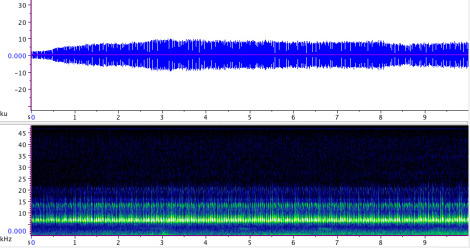

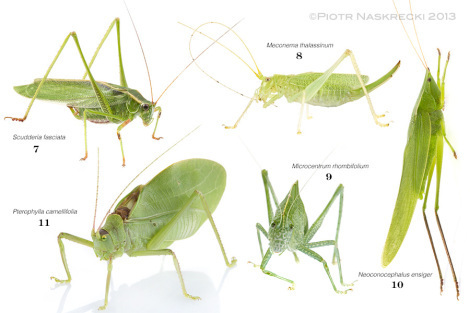

Some of the cricket species I recorded in or near my garden. The number under each name represents the sequence of joining the musical performance in the composite recording below.

Some species, such as the ubiquitous Carolina ground cricket (Eunemobius carolinus), produce calls that are not especially musical, but rather reminiscent of a buzz made by overtaxed power lines. Others, like the Treetop bush katydid (Scudderia fasciata), make irregular, high frequency clicks that show no discernible rhythm. But, as I listen to the evening’s ambience, a repeating pattern begins to emerge. Snowy tree crickets (Oecanthus fultoni) stridulate in a way that is both highly rhythmical and melodious (Joni Mitchell fans will recognize this species in the song “Night Ride Home”), while the frequency-modulated chirps of Field crickets (Gryllus veletis) add a nice, if somewhat irregular, punctuation.

Some of katydid neighbors. Just like with the crickets, the number under each name represents the sequence of joining the musical performance in the composite recording below.

As the night falls more and more species join in. A Two-spotted tree cricket (Neoxabea bipunctata) utters short, piercing cries, usually in sonic pairs, sometimes in series of threes or fours. And although I cannot hear it, I know that the Drumming katydid (Meconema thalassinum), a relatively recent arrival to North America from Europe, is banging one of his hind legs against the bark of the large oak in our garden, creating a percussive line for the rest of the ensemble. Why this species has lost its ability to stridulate and instead evolved a drumming behavior is a mystery, but it is likely that the shift was driven by either a predator or a parasite the had used its (originally) airborne calls to find the singing males and do unspeakable things to them.

And finally, later at night (and later in the season), the True katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia) adds its voice to the chorus. This spectacular insect, whose song is recognizable to anybody who’s ever lived on the East Coast of the US, is the northernmost member of a largely tropical lineage of katydids, the Pseudophyllinae. Despite them being very large and remarkably common insects (you can hear true katydids in the middle of Boston and other large cities), few people ever get the chance to see one – they spend their entire lives high in the canopies of the tallest trees, and are encountered only occasionally, for example when a gust of strong wind knocks them down onto the ground. I have lived surrounded by True katydids for the last 20 years, but can count all my encounters with them on the fingers of one hand. Incidentally, if you ever wondered where the word “katydid” came from, listen to this species’ call. The more northern populations (and thus the ones that the Pilgrims first heard, and apparently were afraid of) have a call consisting of 2-4 syllables that can be interpreted as the sound “ka-ty-did” (or, as the legend goes, “katy-she-did-it”, thus betraying the identity of some murderous lady).

My foot has been tapping since the tree crickets started calling, and now, with the strong beat of the True katydid, I can’t help but imagine melodic lines filling the spaces in between the pulses. I sip my drink and let the mind wander.

A sonogram of a composite recording of most of the orthopteran species singing in my garden. On a good night I can hear them all, but here I decided to add them one by one to the recording to make each species’ song stand out. Click here to listen to this soundscape. Please note that some species (esp. Scudderia and Microcentrum) may not be audible to a certain group of listeners (I am talking about you, men 35 or older; I count myself incredibly lucky for still being able to hear all my local species – but who knows for how long). It will help if you listen to this recording through headphones or external speakers; most built-in computer speakers may not be able to reproduce all frequencies (esp. the low frequency drumming of Meconema). (If you would like to see an animated sonogram with species names appearing as they join the chorus, click here; it is a large file, suitable only for fast internet connections.)

Filed under: Behavior, Crickets, Katydids, Macrophotography, Orthoptera

October 4, 2013

Footprint Cave, Belize

Africa in Mesoamerica – a beautiful, little pool on the floor of the upper chamber of the Footprint Cave; it even has an adjoining pool that looks like the Arabian Peninsula.

It has been a long while since the last update to this blog, mostly because of my hectic travel schedule (in fact, I am typing this on a shaky train ride). But it has been an interesting time, with lots of great photo ops. Last week I joined Alex Wild, John Abbott and Thomas Shahan in Belize to teach BugShot 2013, an intense course in tropical insect macrophotography. Aside from working with a friendly group of photography masters and enthusiastic students it was my first exposure to some of the most interesting members of the troglobitic Mesoamerican fauna as the workshop was held at the Caves Branch Lodge in central Belize, an area famous for its karst formations, replete with deep limestone caves.

The most famous cave in the area is the Footprint Cave, named after calcified Mayan footprints found in the deeper section of the cave, along with a number of artifacts and skeletal remains. The cave was looted in 1994, and many artifacts and remains are now gone, but you can still see there ancient fire places and shards of Mayan pottery. It was quite an unreal and humbling experience to sit next to a pile of ash that might be over 2,000 years old but still looks warm. The cave itself is stunningly beautiful, cathedral-like, with massive stalactites that shimmer in the light of the headlamp. The shallow Caves Branch River flows through it, and as you walk along its bed large catfish and shrimp follow your every step, looking for small aquatic invertebrates flushed from under the sand.

Female cave cricket Mayagryllus apterus, a species endemic to the Caves Branch system of Belize.

As we walked deeper into the cave, leaving behind its large opening and eventually all traces of natural light, we began to discover a multitude of life forms that call this cave their home. Biologists explored Footprint Cave in early 1970′s, but little work has been done since. Many animal species found in the Caves Branch system are likely endemic, and some still await their formal scientific description. I was thrilled to see dozens of long-legged cave crickets Mayagryllus apterus, described only in 1993 from specimens collected in these caves. They were often accompanied by large, equally spindly amblypygids Paraphrynus raptator (Phrynidae), and apparently another, yet undescribed species of the family Charontidae is also present in the cave (and Gil Wizen might have found a third, possibly new amblypygid species). I was hoping to find some dinospiders (Ricinulei) there, alas, no such luck, but flipping rocks on the banks of Caves Branch River revealed a tiny, equally interesting arachnid, a pygmy vinegaroon (Schizomida). The species found in the Footprint Caves is a yet undescribed species of Schizomus, and I would love to be able to collect some specimens and describe them (I need to look into getting some permits for Belize).

A troglobitic isopod crustacean Troglophiloscia sp.; note its lack of pigmentation and eyes, characteristics typical of cave-dwelling organisms.

Silk strands on the cave ceiling, produced by the larvae of predaceous fungus gnats (Keroplatidae: ?Macrocera sp.)

Yet the most interesting organism in the cave was a fly. When we shone the light at the low celling of the cave we could see curtains of thin, glistening strands of sticky silk produced by larvae of predaceous fungus gnats of the family Keroplatidae; I have not been able to identify the species that lives in the Footprint Cave, but it is possibly a member of the genus Macrocera (Macrocerinae). The strands spun by the larvae are covered with droplets of oxalic acid, which trap and kill tiny flying insects, mayflies mostly, found in the cave. Members of a related subfamily Arachnocampinae found in Australia and New Zealand are famous for their bioluminescence, but the ones found in Belize are of the non-glowing variety. Still, it was a beautiful spectacle to see thousands of hair-like strands undulate gently in the breeze caused by a person walking several meters away.

The strands are covered with droplets of oxalic acid, which trap and kill unlucky insects, such as this mayfly, that brush against them in flight.

Everybody was sad to leave the cave, which turned out to be the highlight of our photographic workshop, although the fauna of the rainforest that surrounded the lodge where we stayed was equally interesting. Not being able to collect anything was torture for me, but I hope that some day soon I will be able to come back to Caves Branch, this time wearing only my entomologist’s hat.

A new, yet unnamed species of the pygmy vinegaroon (Schizomus sp.) from the Footprint Cave.

Filed under: Arachnida, Caves, Crickets, Crustaceans

September 12, 2013

Mozambique Diary: The fat coneheads of Gorongosa

Conehead katydid Lanista annulicornis (a.k.a. L. africana) showing its huge, sharp mandibles designed for cutting and crushing grass seeds. They also do an admirable job on human skin.

A few years ago I was at the Museum of Natural History in London to examine several type specimens of African katydids. One of them was the holotype of a conehead katydid Lanista africana, a species described by the infamous 19th century entomologist Francis Walker. (Stories abound about the quality of his taxonomic work, such as the time when he described the same set of insect species twice, each time giving them different names. This, of course, is not unusual and happens to this day, but in his case it was the same box of specimens which he first described in the morning, and then again after lunch, without realizing that he had already given them names.) What caught my eye was an inscription on the label attached to the specimen. In addition to the typical 19th century exactitude in the locality information (“From Africa”) it bore the following note – “Lived 18 months without food.”

The body of the conehead katydid Pseudorhynchus pungens looks just like a blade of grass and few predators can spot them.

Now, without getting into speculations as to why anybody would torture a poor katydid for so long, I was of course highly skeptical about the veracity of such a statement. Eighteen months? That seemed unlikely, to say the least, considering that the average lifespan of an adult katydid is only a few months. But that was before I had a chance to see a live individual of Lanista.

Gorongosa National Park is defined by its extensive grasslands and woodland savannas, just the kind of habitat that African conehead katydids love. If you walk through the tall grass here (and you better have an armed ranger with you if you decide to do so – it is surprisingly easy to miss an elephant hiding a few feet away) chances are that the first insect you see will be a conehead katydid scurrying away. Fourteen species of coneheads can be found here, and one of them is the aforementioned Lanista africana (Which, incidentally, is now known as L. annulicronis. Shockingly, L. africana turned out to be a synonym of L. annulicornis, a species described earlier by – who else? – Mr. Francis Walker.)

When I caught my first Lanista I was surprised at how fat and heavy it felt. Since I needed to preserve a few specimens of this species for the Gorongosa synoptic collection and my own work, I dissected them and discovered that their entire body was absolutely loaded with fat tissue. It was difficult to discern any internal organs in the abdomen because the layer of thick, white fat filled every bit of space – these guys were in a serious need of liposuction. All katydids that I had seen up to that point were rather lean – where did all that fat come from and why did they have it?

African coneheads, as opposed to their New World counterparts, are almost exclusively herbivorous, and the food that they are particularly fond of are grass seeds. Grass seeds are loaded with carbohydrates and lipids, and if you can feed on them effectively you will start storing fat very quickly. (That tasty Big Mac that goes straight into your hips? It is mostly the bun – pure carbs – that does the damage.) Coneheads’ mandibles are seed grinding machines, very sharp and propelled with powerful muscles – this is why coneheads have such huge, elongated heads. Few insects are as good at stripping the husk of a grass seed and getting to the tasty kernel as a conehead katydid.

Conehead katydids’ mortal enemy, the Black-bellied Bustard (Lissotis melanogaster) – I have watched this bird slowly walk in tall grass and expertly pick katydids and grasshoppers that were invisible to me.

Grasslands in Africa are seasonal – the seed bonanza of the rainy season quickly turns into near starvation of the dry one – but if you can store enough energy to survive those few very lean months then your chances of producing the offspring at the onset of rains, perhaps even a second generation of the species in the same year, are greatly improved. I strongly suspect that this is what the coneheads of Gorongosa are doing. The individuals I am seeing now, at the peak of the dry season, are significantly thinner than those I saw here just a few months ago, but I believe that they belong to the same generation. And while I am not going to test it, I now find it more believable that an individual with all its fat reserves intact may be able to survive for a very, very long time without food. And, incidentally, the one species of katydids that is routinely eaten by people in Africa is a conehead Ruspolia consobrina, whose body also contains high levels of nutritious fats.

The genus Ruspolia is represented in Gorongosa by at least six species, some of which may be new to science. R. consobrina is one of the few katydids that are routinely eaten by people in Africa.

The large, elongate head of the conehead katydid Pseudorhynchus hastifer hides powerful grinding muscles and helps this animal blend in among blades of grass.

Filed under: Gorongosa, Katydids, Mozambique

September 7, 2013

Mozambique Diary: The Cat mantis

I decided to christen this impressive praying mantis (Heterochaeta orientalis) the Cat mantis, on the account of its head morphology, but even its defensive behavior reminds me of a cranky cat. (Is there any other kind?)

Arriving in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique at this time of the year, when the grasslands are bone dry and green has all but disappeared from the color palette of this immense ecosystem, I did not expect to see too many insects. Sure, there will always be ants and a bunch of grasshoppers, but the bulk of the insect fauna pretty much disappears until the onset of rains in November. The nights are quite cold when the atmosphere is devoid of the buffering layer of humidity and consequently few insects are active around the lights of the camp. But those that do come are often stunning. Some of the first animals that I spotted when I resumed my nightly patrols around the lights of the Chitengo camp were huge praying mantids Heterochaeta orientalis, whose head morphology immediately brought to my mind a scrawny, long-eared house cat, and that’s what I decided to call them. The Cat mantids are probably some of the largest in Africa, with the females’ body length approaching 20 cm. Males are about 15 cm long, which still makes for an imposing insect.

Despite his huge size, a Cat mantis is virtually impossible to spot in its natural setting of bare branches in the dry woodland savanna of Gorongosa.

Little is known about this species’ biology. I have always found Heterochaeta on tall shrubs and bushes in the woodland savanna, albeit finding them is definitely not easy – despite their size they are some of the most cryptic insects of Gorongosa. It is enough to take your eyes off an individual sitting on a branch for a few seconds to completely lose sense of its whereabouts. When resting on a branch these insects hold their long raptorial legs outstretched to the sides in an uncanny resemblance of two dead twigs coming off a larger branch, very unlike the typical “praying” stance of other mantids, who tend to hold their raptorial legs neatly folded under the pronotum. The pointy protuberances on the Cat mantis’ eyes enhance the illusion that this animal is just a dead, spiky stick. Clearly, their main defense mechanism is to remain undetected by either predator or prey.

While resting on a branch the Cat mantis keeps its forelegs outstretched to the side, enhancing the illusion of being just another dead stick.

But in addition to its superb crypsis the Cat mantis has another trick up its sleeve when it comes to avoiding being eaten. When I first tried to pick up one of the individuals that came to the light, it immediately responded by rearing up its body, opening the front legs to reveal a bright patch on the underside, and fanning its wings to flash a beautiful, contrastingly yellow and black pattern. This color combination signifies danger (think wasps and their stingers) and many potential predators may pause before attacking the Cat mantis, giving it time to fly away. The mantis is bluffing, of course, as other than a very weak pinch it can deliver with its long forelegs it does not have any real weapons or chemical defenses.

When cornered the Cat mantis rears up to make itself look bigger and flashes beautifully yellow and black hind wings that normally lie hidden under the cryptically colored front wings.

Ever since I first came to Mozambique I have been marveling at the praying mantis fauna of Gorongosa, which is the richest that I have seen anywhere in the world. My species list is approaching 50, but the actual number is almost certainly greater. Their abundance is also exceptionally high, and it is not rare for me to get 5-10 individuals of praying mantids in a single sweep of an insect net across the tall grassland. What drives this richness is something that I am interested in understanding, but it may be related to an equally high abundance of orthopteroid insects, the main prey item of many mantids.

A male Cat mantis at sunset.

Filed under: Behavior, Gorongosa, Mozambique, Praying mantids, Wide angle

Piotr Naskrecki's Blog

- Piotr Naskrecki's profile

- 9 followers