Piotr Naskrecki's Blog, page 12

December 27, 2012

The year in review – Part 2

Yesterday I posted a small selection of photos that marked important/interesting events that took place in the first half of 2012, and here is a selection from the last six months.

July. Processing of the entomological material collected in Gorongosa takes up most of the month. Although I spend most of July looking through the microscope, to keep my camera from rusting I document the biodiversity of life in Estabrook Woods outside of Boston. Ambush bugs make a fascinating subject: they are not only pretty, they also try to talk to people.

***

August. I have the good fortune to visit, albeit very briefly, the Galapagos Islands as a leader of a trip organized by the Harvard Natural History Museum. All the icons were there: flightless cormorants, Darwin’s finches, Blue-footed boobies, giant tortoises and, most importantly, the marine iguanas. I make a promise to myself to come back and do a proper study of the Galapagos Nesoecia katydids, which, I am convinced, will reveal a pattern of speciation similar to that seen in other groups at the archipelago. Back home very sad news: our sweet, innocent Max has an enormous tumor in his head. He undergoes a successful surgery, and a radiation and chemotherapy treatment.

August. I have the good fortune to visit, albeit very briefly, the Galapagos Islands as a leader of a trip organized by the Harvard Natural History Museum. All the icons were there: flightless cormorants, Darwin’s finches, Blue-footed boobies, giant tortoises and, most importantly, the marine iguanas. I make a promise to myself to come back and do a proper study of the Galapagos Nesoecia katydids, which, I am convinced, will reveal a pattern of speciation similar to that seen in other groups at the archipelago. Back home very sad news: our sweet, innocent Max has an enormous tumor in his head. He undergoes a successful surgery, and a radiation and chemotherapy treatment.

***

September. Praying mantids are invading my garden! One night I step on the deck and a huge Chinese mantis hits me on the head.

September. Praying mantids are invading my garden! One night I step on the deck and a huge Chinese mantis hits me on the head.

***

October. Maxi has recovered enough from his brain surgery so that we can take him again on long walks in the Estabrook Woods. I giggle like a little girl when on one of our walks I discover a bunch of beautiful oil beetles – I never expected to find them there.

October. Maxi has recovered enough from his brain surgery so that we can take him again on long walks in the Estabrook Woods. I giggle like a little girl when on one of our walks I discover a bunch of beautiful oil beetles – I never expected to find them there.

***

November. Insect activity is winding down, and the arrival of winter moths marks the beginning of a largely lifeless season. But these interesting insects brighten the otherwise gloomy time of year – males come in the hundreds to the lights of our house around Thanksgiving, while the stubby, flightless females are laying eggs in the bark of our maples.

November. Insect activity is winding down, and the arrival of winter moths marks the beginning of a largely lifeless season. But these interesting insects brighten the otherwise gloomy time of year – males come in the hundreds to the lights of our house around Thanksgiving, while the stubby, flightless females are laying eggs in the bark of our maples.

***

December. This year I received the best Christmas gift ever: Kristin commissioned from Canadian artist Sharlena Wood a painting based on my photo of a pair of Gorongosa pygmy chameleons. It is a gorgeous and, I am sure, the world’s only piece of art featuring this endemic and enigmatic Mozambican animal. Thanks K!

December. This year I received the best Christmas gift ever: Kristin commissioned from Canadian artist Sharlena Wood a painting based on my photo of a pair of Gorongosa pygmy chameleons. It is a gorgeous and, I am sure, the world’s only piece of art featuring this endemic and enigmatic Mozambican animal. Thanks K!

Filed under: Macrophotography

December 26, 2012

The year in review – Part 1

I am pretty sure that I am the first photo-blogger ever to come up with the idea to post a series of the most interesting/meaningful photos taken during the passing year (if not the first, then certainly the second, or third, at the most.) It has been a busy and significant year, photographically, scientifically, and emotionally. Since I have a camera grafted to my right hand (well, almost), I was able to capture many of the creatures whom I met during the last twelve months, and here are a few highlights:

January. I begin to work in earnest on my next book, which, among other things, will explore the complex ecosystem of modern caves – our homes. Once I really start paying attention, I am astounded by the number of species that share the living spaces of our house with us, and the diversity of ecological niches they occupy: I find detrivores, herbivores, parasites, grazers, browsers, necrovores, sit-and-wait predators, and social animals. Some are well-established, others were just visiting; many are here all year round, a few are seasonal; and some are native, and others are aliens from other parts of the world.

January. I begin to work in earnest on my next book, which, among other things, will explore the complex ecosystem of modern caves – our homes. Once I really start paying attention, I am astounded by the number of species that share the living spaces of our house with us, and the diversity of ecological niches they occupy: I find detrivores, herbivores, parasites, grazers, browsers, necrovores, sit-and-wait predators, and social animals. Some are well-established, others were just visiting; many are here all year round, a few are seasonal; and some are native, and others are aliens from other parts of the world.

Camel crickets (Diestrammena asynamora) are cave-dwelling animals that came from Asia via Europe to North America. Rob Dunn’s lab is now conducting a continent-wide census of these insects.

***

February. With nasty winter outside the window, I find refuge from the deadly season in trying to document the entire life cycle of a pet praying mantis, African Sphodromantis lineola. Here a female is undergoing her final molt.

February. With nasty winter outside the window, I find refuge from the deadly season in trying to document the entire life cycle of a pet praying mantis, African Sphodromantis lineola. Here a female is undergoing her final molt.

***

March. I spend the entire month of March in a tent: I am part of a team of biologists conducting a biodiversity survey of the spectacular lowland rainforest of southern Suriname. Highlights of the survey included finding a number of new to science species of katydids, and almost tripping over the largest spider in the world, Theraphosa blondi.

March. I spend the entire month of March in a tent: I am part of a team of biologists conducting a biodiversity survey of the spectacular lowland rainforest of southern Suriname. Highlights of the survey included finding a number of new to science species of katydids, and almost tripping over the largest spider in the world, Theraphosa blondi.

***

April. Back home, Massachusetts spring is in full bloom and young katydids are everywhere. Alas, the Roeseli’s katydid (Metrioptera roeselii) is an invasive species, which probably contributes to the decline of native katydids.

April. Back home, Massachusetts spring is in full bloom and young katydids are everywhere. Alas, the Roeseli’s katydid (Metrioptera roeselii) is an invasive species, which probably contributes to the decline of native katydids.

***

May. Because of my life-long interest in Africa and a decent publishing record on southern African orthopterans, I am invited to join a team from Harvard University to explore the insect diversity of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. Gorongosa turns out to be one of the most amazing, biologically-richest places I have had the privilege to visit. Situated at the southernmost tip of the African Great Rift Valley, it encompasses an astounding variety of terrain, including afromontane rainforest and deep, unexplored limestone gorges. Orthopteran and dictyopteran diversity is through the roof, and I am thrilled to find the giant grasshoppers Lobosceliana cinerascens.

May. Because of my life-long interest in Africa and a decent publishing record on southern African orthopterans, I am invited to join a team from Harvard University to explore the insect diversity of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. Gorongosa turns out to be one of the most amazing, biologically-richest places I have had the privilege to visit. Situated at the southernmost tip of the African Great Rift Valley, it encompasses an astounding variety of terrain, including afromontane rainforest and deep, unexplored limestone gorges. Orthopteran and dictyopteran diversity is through the roof, and I am thrilled to find the giant grasshoppers Lobosceliana cinerascens.

***

June. Still in Mozambique, documenting insect life. Sitting there, on the edge of a deep limestone gorge in the middle of the night, I feel very insignificant. And happy.

June. Still in Mozambique, documenting insect life. Sitting there, on the edge of a deep limestone gorge in the middle of the night, I feel very insignificant. And happy.

Stay tuned for photos from the second half of the year but, in the meantime, head on to Facebook and click “Like” on the Gorongosa National Park’s page.

Update: See the second half of the photographic review of 2012.

Filed under: Macrophotography

December 23, 2012

They grow so fast

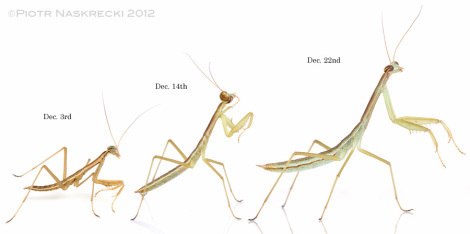

The Chinese mantis hatchlings, which quite unexpectedly overran my house a few weeks ago, are growing like crazy. If all goes well, this cohort should be laying eggs by spring, and thus I should be able to return them to my garden (although they are an introduced species, Chinese mantids are already well established in my neighborhood, and thus I don’t feel too terrible about releasing them.)

Instars I, II, and II of the Chinese mantis (Tenodera parasinensis)

Filed under: Praying mantids

December 20, 2012

Insect-mimicking snakes?

A young ringed python (Bothrochilus boa) from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

New Guinea has quite a few venomous, really dangerous snakes. Death adders (Acanthophis), taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus), or Papuan blacksnake (Pseudechis papuanus) are elapid snakes that have caused many human fatalities on the island. But the one thing that New Guinea does not have is coral snakes. The only venomous snake that looks like one is a hatchling of the small-eyed snake (Micropechis ikaheka), whose posterior half has alternating white and dark rings. It is therefore somewhat surprising that young ringed pythons (Bothrochilus boa), non-venomous and essentially harmless reptiles (unless you are a mouse, that is) advertise their presence with vivid, orange and black coloration. Their entire body has a shiny gloss to it, and it is impossible not to notice this animal as it glides through the leaf litter and low branches.Aposemtic walking stick Megalocrania batesi from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

I puzzled about this seemingly counterintuitive behavior – why advertise yourself if you have nothing to back it up with, and local predators have never been exposed to venomous snakes of such a coloration? Is it still Batesian mimicry if there is no harmful model? Or perhaps the snake is colorful simply for the sake of being pretty (rather unlikely.) But then, one day while looking for katydids hiding among the leaves of Pandanus plants, I stumbled upon a giant walking stick, Megalocrania batesi. I was immediately struck by how similar its coloration was to that of a young ringed python that I had photographed a few days earlier: shiny black body, with bright orange legs, plus bright yellow spots. But why would a snake mimic a walking stick?Burying beetle Nicrophorus heurni from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

As it happens, many walking sticks, including the genus Megalocrania, are capable of synthesizing de novo noxious, repellant chemicals (other insects usually sequester such compounds from their food plants), which they then spray at the attackers with surprising accuracy. These compounds, mostly monoterpenes (e.g., iridodial, nepetalactone, anisomorphal), quinoline, and pyrazines, act as powerful deterrents to a wide range of predators, from ants to lizards to birds and rodents (opossums, however, seem to relish toxic walking sticks.) For the young python a walking stick that is avoided by all the same predators that like to munch on small snakes could be a pretty good model to imitate. And a few days later I also found in the same rainforest habitat a burying beetle (Nicrophorus heurni), which showed a similar combination of shiny black and orange coloration. Like the aposematically colored walking sticks, these insects are avoided by many predators thanks to their ability to spray the attacker with some of the stinkiest substances in nature, including phenol, indole and, most importantly, skatole (you can guess what the last one smells like.)A single, casual observation obviously does not constitute a proof that ringed pythons mimic insects. But this would not be the first example of a vertebrate mimicking an aposematic insect: in southern Africa a small lizard Heliobolus lugubris mimics black and white Anthia ground beetles, known to have powerful chemical defenses. And if a caterpillar can mimic a snake, I don’t see why a snake could not mimic an insect.

![Adult ringed pythons lack the bright, conspicuous coloration of the juveniles – it may be difficult to mimic a walking stick if you are over a meter long! [Canon 1D MkII, Canon 16-35mm, speedlight Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381473054i/4922808.jpg)

Adult ringed pythons lack the bright, conspicuous coloration of the juveniles – it may be difficult to mimic a walking stick if you are over a meter long! [Canon 1D MkII, Canon 16-35mm, speedlight Canon 580EX]

Filed under: Beetles, Behavior, Phasmatodea, Reptiles

December 17, 2012

Parktown Prawn

Male Parktown Prawn (Libanasdus vittatus) from the Modjadji Cycad Reserve in Limpopo. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

Around this time of the year, the lucky inhbitants of Johannesburg in South Africa are often visited by this handsome beast, known as the Parktown Prawn (Libanasidus vittatus). Originally found only in indigenous forests of northeastern part of the country, in 1960′s these cricket and katydid relatives (Anostostomatidae) started appearing in gardens and houses around Jo-burg. It is not quite certain what attracted them there, but it was likely a combination of the relatively high humidity of suburban gardens, combined with the lack of their natural predators, mongooses and monitor lizards, in this anthropogenic environment.

These beautiful insects are feared by many, but of course they are completely and utterly harmless. The massive jaws seen in the males are used only in territorial battles with other males, and cannot be used to stab or bite a person. Their only defense is, unfortuntely, rather odorous defecation. But if left alone they make a beautiful addition to the South African urban ecosystem.

![Male Parktown Prawn (Libanasdus vittatus) from the Modjadji Cycad Reserve in Limpopo. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381317367i/4697612._SX540_.jpg)

Female Parktown Prawns lack the huge processes on their mandibles. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

Filed under: Orthoptera

December 13, 2012

Mantidflies

A mantidfly emerging from a spider egg sack on a tree trunk in Cambodia. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, MT 24EX twin light]

I was busily looking for bark mimicking katydids in Cambodia, when I noticed out of the corner of my eye some slow movement on the trunk of a nearby tree. At first I couldn’t quite grasp what I was seeing – a yellow, wormy thing, wiggling its way out of the bark. But after a second I realized that I was seeing the remarkable spectacle of an adult mantidfly emerging from a spider sack after having spent its larval development feasting on spider eggs. I looked more closely and spotted the mother spider near the egg sack, blissfully unaware that she was now guarding the empty coffin of her once future children. The entire process lasted only a few minutes, during which the spider looked right at the monster that had just devoured her eggs, comprehending nothing. Unlike most winged insects, which need to spend some time expanding their wings and pumping them with air in order to be able to fly, this mantidfly emerged from its pupal casing fully formed and, within a few seconds of full emergence, it flew away. The spider kept guarding the egg sack.The female two-tailed spider (Hersilia sp.) is still guarding her egg sack, unaware that all her eggs have probably been devoured by a mantidfly; the inset shows an empty pupal skin of the recently hatched mantidfly. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, MT 24EX twin light]

Mantidflies are amazing insects. They are not true flies, of course, but rather members of the family Mantispidae (Neuroptera), closely related to antlions and green lacewings. This means that they are not related to praying mantids either, although they could be easily confused with them. Like mantids, mantidflies have large, raptorial front legs on a long, neck-like prothorax. They also share big, bulging eyes, and a similarly excellent vision. But rather than holding their front legs pointing forward, like mantids do, mantidflies hold them in a somewhat contorted, vertical position.Mantidfly (Leptomantispa sp.) from Saba, Dutch West Indies. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX + MT 24EX twin light]

Mantidflies also share with praying mantids their love of live prey – mostly small, flying insects, which they catch with a surprising speed. Like mantids, they are also not above munching on members of their own species, a behavior which sometimes takes place during mating. Unlike mantids, however, the male mantidfly is as likely to eat the female as the other way around.Mantidfly (Pseudoclimaciella sp.) from Botswana devouring a planthopper. [Canon 10D, Canon MP-E 65mm macro, Canon MT-24EX twin light]

As holometabolous insects, mantidflies undergo a complete metamorphosis, and the larvae look nothing like the graceful adults. The first instar is tiny and highly mobile, whereas the two subsequent ones are grub-like, with long, piercing mandibles. Many species are predators of spider eggs, others feed on larvae of beetles, flies, and moths. Those species that feed on spider eggs must overcome quite a few obstacles before they can continue their development. After hatching from an egg laid by a female mantidfly, the larva attaches itself with a special “sucker” on its abdomen to the substrate, and waves its outstretched legs back and forth, waiting for a passing spider. But the spider that happens to be passing by is not always a mature female ready to lay eggs. No matter – the larva will attach itself to any spider and bide its time. If the spider is a male, it will try to get on a female’s body when the spiders are mating. If the spider is immature, it will remain on the host as it grows, hiding in the book lungs (breathing organs) of the spider when the animal molts, to avoid being shed with the spider’s old cuticle. Once the female spider is ready to lay eggs, the mantidfly larva allows itself to be wrapped in a silk sack with the eggs, and begins to devour its content.There are about 400 species of mantidflies worldwide, of which most are found in the tropics, and only about 13 are known from North America N of Mexico. This summer I was pleasantly surprised to find a wasp-mimicking Climaciella brunnea near Boston, and next summer I will be looking for spiders carrying their parasitic larvae.

Several species of mantidflies are mimics of wasps. North American Climacella brunnea mimics polystine wasps, and local color morphs of this species resemble the dominant wasp species in the area (this individual is from Massachusetts.) [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]

![Mantidfly (Dicromantispa sp.) from Costa Rica. [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803555.jpg)

Mantidfly (Dicromantispa sp.) from Costa Rica. [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]

Filed under: Neuroptera

December 10, 2012

Weevils

A Costa Rican weevil Cholus cinctus in flight. [Canon 1D MkII, Canon 16-35mm, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]

J. B. S. Haldane, the British geneticist, is often quoted for proclaiming, “The Creator, if He exists, has a special preference for beetles.” (*) With between 275,000 to 350,000 described species of beetles it is hard to argue with this statement. Of these, about 60,000 species belong to a single family, the weevils (Curculionidae), making it not only the largest among beetles, but also of all living organisms. Their evolutionary success may be based in the morphology of their mouthparts, which in most species are situated at the tip of a long rostrum or snout. This allows such species to bore deep holes in even the hardest seeds or nuts in order to deposit their eggs there, providing developing larvae with a safe environment and a rich supply of food. It is also certain that the weevils’ success is related to the diversification of flowering plants, which began in the Cretaceous. A process known as coevolution, which can be compared to an arms race between plant-feeding beetles and their hosts, has led to a steadily increasing specialization of beetle species in response to the evolution of better defensive strategies of plants, and an almost exponential increase of their numbers.[An excerpt from my book "The Smaller Majority."]

(*) The exact wording of Haldane’s famous phrase has never been confirmed, but only this sentence appeared in print in a summary of his speech given to the British Interplanetary Society in 1951; the wording that includes the phrase “inordinate fondness of beetles” is probably apocryphal.

The bearded weevil (Rhinostomus barbirostris) is a species with an interesting sexual polymorphism. A proportion of males in each population is smaller than other individuals of this sex, and resembles females in their appearance. This allows them to sneak unnoticed past the larger males and approach the female without being challenged (Costa Rica). [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro]

![The long “neck” of the giraffe weevil (Trachelophorus giraffe) is used in ritualized male combat (Madagascar). [Nikon D1X, Sigma 180mm macro]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385785688i/7227540.jpg)

The long “neck” of the giraffe weevil (Trachelophorus giraffe) is used in ritualized male combat (Madagascar). [Nikon D1X, Sigma 180mm macro]

Filed under: Beetles

December 6, 2012

Mass migration

Flightless brown locust hoppers (Eastern Cape, South Africa) [Canon 5D, Canon 16-35mm, MT 24EX twin light]

Annual mass migrations of zebras, wildebeest, Thompson gazelles, and other assorted ungulates on sweeping, dry African plains are the source of some of the most evocative and celebrated images of our world at its finest. Cue in the blazing red orb of the setting sun as the endless string of magnificent, heroic silhouettes passes across the horizon and, at the sight of such a pure and epic spectacle of life, your heart is bound to swell with that uplifting feeling of being one with nature. A brief sense of moral outrage may pass through your mind at the recollection of those unscrupulous people who destroy the natural habitats and passageways of the valiant beasts for reasons no other than to plant more crops or graze more cattle. “How selfish we humans are,” you muse, “why can’t we leave nature alone?” I, of course, have exactly the same reaction. But at the same time my entomophilous mind can’t help but notice a strange disparity in our concern for one group of migratory organisms and a total disregard, a raging abhorrence in fact, for others. Africa is a place where many animals move en masse in search of greener pastures, and the one that I find particularly interesting is a small, inconspicuous grasshopper known under the scientific name of Locustana pardalina.Brown locust (Locustana pardalina) [Canon 5D, Canon 16-35mm]

Solitary most of the time, every now and then millions of these insects will band together and, just like the grazing mammals we so admire and love to watch, march across South African karoo to look for more grass. Wingless at first, they hop across parched terrain in huge, reddish waves, but as soon as the animals pass their final molt and grow a pair of sturdy wings the whole group takes up to the air. As they flew over my head against the cloudless sky the spectacle was truly breathtaking. The rustling of thousands of wings filled the air, and each animal took on an almost ethereal quality as the light of the sun filtered through their bodies. I saw this scene only twice in my life, and both times the sight felt to me as majestic as the celebrated migrations of the Serengeti plains. After a while the enormous cloud of insects disappeared over the horizon, and probably found a good patch of greenery, where they landed, and started to feed.Clearly, I am not a South African farmer, and my description of the swarm of Brown locusts is a departure from the traditional depiction of these insects, where words such as “devastation,” “tragedy,” and “hunger” are frequently evoked. There is no denying that Brown locusts cause considerable damages to cereal crops, which to them are no different from grassy plains that used to exist there before the arrival of organized agriculture. The economic losses and human suffering that they cause clearly justify the efforts to control them, but some of the knee-jerk responses to locust swarms may do more harm than good. Broad-spectrum pesticides used to exterminate locusts kill not only the target species, but also countless other organisms, such as pollinators or beneficial parasitoids that control outbreaks of other pests. To add to the problem it is difficult to predict where and when the next outbreak will take place. There is some evidence of their correlation with the El Niño temperature oscillations of southern Pacific surface waters, on their own difficult to predict events.

[An excerpt from my book "Relics: Travels in Nature's Time Machine"]

![A swarm of brown locusts in Eastern Cape, South Africa [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100-400mm]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381533286i/4993237._SX540_.jpg)

A swarm of brown locusts in Eastern Cape, South Africa [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100-400mm]

Filed under: Behavior, Orthoptera

December 3, 2012

More babies

A proud mother with one of her babies [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]

Earlier today Kristin was reading on the couch, when she noticed a small insect crawling up the wall. “It is either a very small mantis or an assassin bug”, she opined, exhibiting some pretty good entomological expertise. I was not expecting to see either but, sure enough, it was a small praying mantis. Then we noticed one more, and about fifty additional ones, as they kept escaping from a container that held their mother, a Chinese mantis (Tenodera parasinensis) (the very individual that I featured in an earlier post about mantis ears.) I knew she had laid some eggs, but these were not supposed to hatch until spring! Soon the entire household, dogs included, were busy trying to corral tiny, jumpy insects that overran the room.They are now safely sequestered in several containers, and munching on fruit flies. It is interesting that, as it became evident to me today, this species does not require a winter diapause in order to hatch. Eggs of another common introduced species, the European mantis (Mantis religiosa), must spend several weeks in freezing weather in order to develop and hatch, which also limits this species’ distribution to areas that have a clearly pronounced, cold winter. But the Chinese mantis can colonize areas that either have or don’t have winter, and I suspect that in the coming decades this species is going to outcompete the European mantis in places where they now co-occur.

![A newly hatched CHinese mantis (Tenodera parasinensis) [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386421514i/7360939.jpg)

A newly hatched Chinese mantis (Tenodera parasinensis) [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]

Filed under: Praying mantids

Piotr Naskrecki's Blog

- Piotr Naskrecki's profile

- 9 followers

![A young ringed python (Bothrochilus boa) from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381473054i/4922805.jpg)

![Aposemtic walking stick Megalocrania batesi from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381473054i/4922806.jpg)

![Burying beetle Nicrophorus heurni from Papua New Guinea. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381473054i/4922807.jpg)

![Male Parktown Prawn (Libanasdus vittatus) from the Modjadji Cycad Reserve in Limpopo. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381317367i/4697611._SX540_.jpg)

![Mantidfly emerging from a spider egg sack on the tree trunk in Cambodia. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, MT 24EX twin light]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803550.jpg)

![The female two-tailed spider (Hersilia sp/) is still guarding her egg sack, unaware that all her eggs have probably been devoured by a mantidfly; the inset shows an empty pupal skin of the recently hatched mantidfly. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, MT 24EX twin light]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803551.jpg)

![Mantidfly (Leptomantispa sp.) from Saba, Dutch West Indies. [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 100mm macro, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX + MT 24EX twin light]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803552.jpg)

![Mantidfly (Pseudoclimaciella sp.) from Botswana devouring a planthopper. [Canon 10D, Canon MP-E 65mm macro, Canon MT-24EX twin light]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803553.jpg)

![Several species of mantidflies are mimics of wasps. North American Climacella brunnea mimics polystine wasps, and local color morphs of this species resemble the dominant wasp species in the area (this individual is from Massachusetts.) [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1382305928i/5803554.jpg)

![A Costa Rican weevil Cholus cinctus in flight. [Canon 1D MkII, Canon 16-35mm, 2 speedlights Canon 580EX]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385785687i/7227538.jpg)

![The bearded weevil (Rhinostomus barbirostris) is a species with an interesting sexual polymorphism. A proportion of males in each population is smaller than other individuals of this sex, and resembles females in their appearance. This allows them to sneak unnoticed past the larger males and approach the female without being challenged (Costa Rica). [Canon 1Ds MkII, Canon 180mm macro]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1385785687i/7227539._SY540_.jpg)

![Flightless brown locust hoppers (Eastern Cape, South Africa) [Canon 5D, Canon 16-35mm, MT 24EX twin light]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381533286i/4993235.jpg)

![Brown locust (Locustana pardalina) [Canon 5D, Canon 16-35mm]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381533286i/4993236.jpg)

![A proud mother with one of her babies [Canon 7D, Canon 100mm macro, 3 speedlights Canon 580EXII]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386421514i/7360938.jpg)