Matador Network's Blog, page 2185

November 11, 2014

Signs you're from Washington state

Image by Patrick Gage

1. “You go,” “No you go” wars at 4-way stops have always been the most predictable part of your morning commute.

“My over-priced, sub-par Venti Starbucks Veranda Roast is growing cold and I’m not even in the office yet. Just fucking go already.”

2. Your most dreaded chore growing up was pressure washing.

In Washington, we fight water with water. Unfortunately the high pressure with which we treat moss-stained patios numbs our hands through tortuous, vibrating shockwaves. It’s a process so uncomfortable that even humming the tune to David Bowie’s “Under Pressure” can’t end the discomfort. Thanks nonetheless, Dave.

3. In high school, the girls asked the guys to “tolo,” not to a “Sadie Hawkins Dance.”

She asked you with “tolo?” scribbled on a crumpled up piece of notebook paper that she borrowed from you. “Sadie Hawkins Dance?” just wouldn’t have looked as good.

4. You don’t drink Rainier — you drink Raw-nee-ay, because cheap beer tastes less like cheap beer when pronounced with a French accent.

Whether you’re at a watering hole in Eastern Washington or at a stuffy, beanie-infested hipster bar on Capitol Hill, they probably have Rainier tall boys, and they’re probably always on special.

5. You’ve eaten a bag of Dick’s.

As a kid you savored the obligatory stop for a Dick’s Deluxe, fries, and chocolate shake on the way home from a basketball game in Emerald City. As a twenty something you almost always find yourself with bag of Dick’s in hand after a particularly boozy night with friends that calls for consumption of “all the fries.”

6. You’ve accepted the maddening reality that Kitsap County still can’t pronounce bags.

Dammit all, it’s “bags” not “begs” or “baigs.” You’re making grocery-baggers’ jobs more miserable than they already are. You’d probably call them “grocery beggers” anyway.

7. You’ve always been well stocked up on Theo’s Chocolate, because Hershey’s is for the poorly-developed taste buds of a torch-wielding Neanderthal.

Theo’s chocolate is everything that’s right about Seattle — the first organic and fair trade chocolate factory in North America. At last, I can feel morally superior when I consume excessive amounts of chocolate. The only downside is a few bars cost half a paycheck, which funnily enough has inspired a dumpster-diving rage among like-minded broke-off-their-ass individuals that burrow for the chance of getting their hands on just one tossed brick of choco heaven.

8. You’ve been on a ferry to Bainbridge Island before, and it kind of sucked.

Torrential downpours and aggressive gusts of wind are a given out here. You’d think modern day engineering would have given us ferries better tuned for handling white caps and relentless chop. Unfortunately, nope. You forgot to steer clear of the stadium-priced pastries and Alaskan Ambers served on board throughout the ride, so naturally, you got seasick.

9. Your four seasons growing up were fall, winter, spring, and blackberry picking.

You were one of those kids who, in the process of trying to fetch a bowl of blackberries, managed to cut up every inch of exposed arm / leg — all for a damn pie. What happened to outdoor pools and lemonade stands in the summertime, and why are blackberry bushes so aggressive?

Signs you don't know Colombian food

Image by Sandor Weisz

1. You find arepa incredibly dull.

Good old arepa. How such a basic food could become such a source of excitement and joy is a testament to Colombian optimism. To most visitors the very idea of eating a flat cornbread once, often twice, a day would prompt an exasperated sigh and a slump of the shoulders. Yet Colombians, especially those from Antioquia, see the arepa in a different light. Whether it’s laden with ground beef, avocado, and cheese, or coated in butter and sprinkled with salt, its appeal never diminishes — so much so that consuming the thing three times a day is seen as a normal practice.

2. You think mango is an exotic fruit.

Wandering through the fruit section in a Colombian grocery store for the first time is like watching a freak show. You find yourself grabbing onto the person next to you and pointing at strange things in horror. “What the hell are those green spikey footballs?” you shriek. After calming you down, the shopper will say “They’re just guanabana, they won’t hurt you.”

Then you recoil in horror and later delight in cracking open a granadilla and sucking out the sweet frog-spawn interior. Soon you become addicted to these strange exotic fruits. You find your shopping cart bursting with multi-colored lulo, maracuyá, pitahaya, tomate de árbol, mangostino, brevas, and guayaba.

More like this: 8 things people get wrong about Colombia

3. You acknowledge a limitation to cheese.

As well as being optimistic eaters, Colombians are also incredibly inventive when it comes to cheese. Who would think of sprinkling cheese onto ice cream? Colombians, that’s who! And they don’t stop there. A chunk of cheese is often plopped into a steaming cup of hot chocolate. And plantains are often roasted and seasoned with, you guessed it, cheese.

4. You wait until a mango is ripe before consuming it.

Yes, Colombians revel in their sweet mangos, but they also hold in high regard the unripe version (called mango biche). Stringy spaghetti-like bits of green mango are often peddled by street vendors and used as an accompaniment for drinks in bars. The usual soft, slippery texture of a ripe mango is replaced with a hard crunch and a bitter taste that gets offset with salt and lemon used as seasoning.

5. You fail to see the potential of mixing certain foods.

Things happen in Colombia that you never before thought possible. You buy a popsicle from a street vendor and think the transaction is over. Think again. Before wishing you a good day, the street vendor holds out a small packet. “Sal?” Yes, he has just asked if you want salt with your flavored ice. Thinking he’s being sarcastic, you laugh and say, “And some pepper, too, while you’re at it.” Except he doesn’t laugh. He reaches into his sack and hands you a small sachet of pepper.

You think soup is just an appetizer.

“Is that all you’re eating? Just a soup?” you say to a Colombian dining companion. She smiles knowingly. “Just wait till you see it.” The ajiaco ‘soup’ which arrives contains chicken, three types of potatoes, corn, and a local herb called guasca. Instead of bread its sides are a mound of rice, avocado, capers, and cream. It’s a meal in itself, and a good one at that. And it’s not the only one. Sancocho is a thick soup cooked with various root vegetables, herbs, and different types of meat, also accompanied by rice and avocado. Other wholesome offerings are mondongo, cuchuco de cebada and sopa de patacón.

6. You don’t really know sweet.

Often after a menú del día, a set three-course meal usually at lunch time, you will be given a dessert. When I say dessert I mean a matchbox-sized candy. You wonder how this can be labeled ‘dessert’, until you nibble at the end and jump out of your seat with a sugar rush akin to downing two cans of Red Bull. The candy or dulce comes from the much-used sugar cane, or a mixture of fruit and sugar. A raw version of sugar cane called panela is also widely consumed, mixed with hot water. This aguapanela is believed to have great healing powers which professional Colombian cyclists have used to improve their performance.

7. You think an ant is a pest…not a gateway to a better sex life.

You might think oysters and chilies are the best aphrodisiacal foods, but not in northern Colombia. Here locals believe a certain type of ant contains the same properties needed to boost your sex drive. Hormigas culonas — “fat-bottomed ants” — are fried and sold by street vendors, especially during rainy season. They’re also given as a wedding present to make sure the marriage gets off to the best of beginnings.

November 10, 2014

11 idioms only Brits understand

Photo: Alex Masters

1. Pop one’s clogs

You don’t get much more British than this. To pop one’s clogs is a euphemism for dying or death.

Example: “No one knew he was about to pop his clogs.”

2. That went down a treat

If something goes down a treat, then it was thoroughly enjoyed.

Example: “That cake went down a treat.”

3. Take the mickey

Us Brits love to make fun of and tease each other and that’s exactly what ‘taking the mickey’ means. You can also say ‘take the mick.’

Example: “Stop taking the mickey out of your brother.”

More like this 8 lies you tell yourself when you move to London

4. Itchy feet

This refers to when you want to try or do something new, such as travelling.

Example: “After two years in the job she’s got itchy feet, so she’s going to spend three months in Australia.”

5. At a loose end

If you’re at a loose end, it means you’re bored or you have nothing to do.

Example: “He’s been at a loose end ever since he retired.”

6. Another string to your bow

This means to have another skill that can help you in life, particularly with employment.

Example: “I’m learning French so I’ll have another string to my bow.”

7. As the actress said to the bishop

This is the British equivalent of ‘that’s what she said.’ It highlights a sexual reference whether it was deliberate or not.

Example: “Blimey, that’s a big one — as the actress said to the bishop.”

8. Bob’s your uncle (and fanny’s your aunt)

This phrase means that something will be successful. It is the equivalent of ‘and there you go,’ or as the French say ‘et voilà!’ Adding the ‘and fanny’s your aunt’ makes you that much more British.

Example:

A: “Where’s the Queen Elizabeth Pub?”

B: “You go down the road, take the first left and Bob’s your uncle — there it is on the corner!”

9. Cheap as chips

We love a good bargain, and when we find one we can’t help but exclaim that it’s ‘as cheap as chips.’

Example: “Only a fiver for a ticket — cheap as chips mate!”

10. Look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves

This is one that our grandparents have told us our whole lives. If you take care not to waste small amounts of money, then it will accumulate into something more substantial.

11. Nosy parker

This is for all the nosy people of the world. A ‘nosy parker’ is someone who is extremely interested in other people’s lives.

Example: “Stop being such a nosy parker! They’re having a private conversation!”

9 ways dating a guy from Maine changes you

Photo: will law

1. You no longer consider dinner and a movie to be the perfect date.

In fact, he never really asked you out. You just went for a motorcycle ride down Route 1 and a hike up Pigeon Hill, and now you’re official. Maine guys don’t necessarily take you out on the town; they show you where they’re from. That’s the real test.

2. You used to just look at nature; now you’ve been immersed in it.

Maine men — and women — take the outdoors very seriously. When he wants to take you camping for the weekend, he wastes no effort in doing so. He loads the boat with enough camping gear to shelter a small village, hooks it all to the truck, unloads everything at Tunk Lake, motors you across, and sets up a kickass campsite on the beach.

You’re then required to hike up Black Mountain so he can point out all the trees. (Birch! Spruce! Cedar!) And birds. (Chickadees! Woodpeckers! Loons!) And any other thing he believes to be of importance to you. (Deer poop! Porcupine quills! PBR cans!)

3. You’ll now pee anywhere.

One of the most crucial factors your relationship most likely depends on is whether or not you can drop trou and pop a squat wherever. With the amount of time you both spend cruising back roads, trudging through brush, and partying in the middle of complete Stickville nowhere, you can’t afford to be modest. No self-respecting Maine guy’s going to drive out of his way to find an actual toilet for you to hover over. So you’ve learned to do as the Maine gals do and throw embarrassment out the window.

4. Through the power of association, you’re now a badass.

You guys logged 400 miles on the V-Max this summer when you went to a biker conference in New Hampshire. You were bored last weekend, so you hiked the entire Bold Coast Trail. You couldn’t sleep last night, so you kayaked down the Narraguagus. You drove from Florida to Maine last winter in a Subaru Outback, which was hauling a skiff, which had a 1200cc Yamaha in it.

No big deal. You guys do what you want.

5. All of a sudden, you don’t really give a shit.

“Don’t sweat the small stuff” encapsulates Maine culture. Before you started dating this guy, you were pretty uptight about all sorts of random stuff. You often wondered: Are these ballet flats sensible for this backwoods pit party? (No.) Does my hair look greasy because I haven’t had access to running water in six days? (Yes.) Is he really getting out of his truck to shoot that deer? (Most likely.)

Your Maine guy’s taught you to just relax. Don’t obsess! There’s absolutely nothing to worry about over here!

6. Baked beans, sausage, and Cabot tomato-basil cheese are appropriate at any time of day.

It’s the ultimate camping meal, but you’ve accepted that this is the only thing he’s going to feed you. Ever.

7. You can’t go anywhere without being introduced to everyone there.

If he doesn’t know someone, their parents, and their parents’ parents, he intends to find all of that out. You’ve reached the summit of a mountain only to watch him walk over to the single other person there and introduce himself. For what reason? You haven’t figured that out yet. But once he knows a person, he doesn’t forget them, and they certainly don’t forget him. You guys have been walking down the street in New Orleans and been stopped by a guy who remembered him from a bar in Asheville, North Carolina, five years ago.

8. You’re much braver than you used to be.

He thinks you’re brave because you’ll go anywhere with him. You think you’re not brave; you’re just trying to impress him. Until one day you wake up and go kayaking alone in Gouldsboro Bay — just because you want to. And even though you’re alone, you realize your phobia of drowning is abating because your sense of adventure is growing. And, later, when you’re both cruising down Route 9 on the motorcycle and two bears run out in front of you, you’re more concerned with getting a clear picture than you are of getting attacked by two bears.

9. You have a hard time telling who you’re really in love with — the state of Maine or him.

So you spend a winter in Florida and realize it’s probably him.

What people get wrong about Colombia

Image by Santiago Galvis

1. It’s just a massive jungle.

Sure, Colombia has the Amazon, the most biodiverse jungle on Earth. But Colombia is also so much more than that. Just look at Los Llanos. This grassland plain covers vast expanses of land in eastern Colombia and is home to rope-swinging cowboys who herd cattle, tell mysterious folk stories, and do other cool cowboy stuff.

Then there’s Guajira Desert in the northeast of the country. Colombia even has snow. Los Nevados National Park, in the center of the Colombian Andes, has the largest relief of any coastal mountains in the world, with full on alpine peaks and ice-climbing opportunities. There’s hot springs, marble caves, multi-colored rivers, two oceans, islands, a 2000-meter-deep canyon, mud volcanoes, modernized cities…I guess one could say that Colombia is quite a diverse “jungle.”

2. Tourists will be kidnapped.

“If I bring a camera, will I be a walking target for kidnappers?” That’s what a friend asked me before coming to Colombia last year. I assured him that he and his Sony NEX-3 would not be a target for any potential kidnappers. Once considered the world-kidnapping capital, Colombia is much safer than it was a decade ago. Statistics show that in 2013 there were a reported 292 cases of kidnapping — a 92% fall from 2000. Also consider that most kidnappings are against human rights workers and oil workers, not Johnny-tourist types.

3. Everybody loves Shakira.

When I was in Buenos Aires, I often began conversations with fellow soccer fans with, “That Lionel Messi. Hell of a player isn’t he!” Most would shrug their shoulders and simply say, “He’s no Maradona.” The problem is that unlike Maradona, Messi never spent his soccer youth in his native Argentina — a decision which left a bitter taste in the mouths of many Argentinians. They see Messi as a great player, but a great European player, not a true Argentine legend.

The same can be said for Shakira. One would think that this international superstar singer is revered back in her native country. However, this is not the case. The truth is that, like Messi, her decision to leave her native country caused many Colombians to doubt her patriotism. To make matters worse, she once sang the wrong words to the Colombian national anthem…something music idol Juanes would never do.

4. It’s ‘Columbia’, not ‘Colombia’.

Don’t believe everything you read in the press, on TV news networks, or on Twitter. For decades people have been misspelling Colombia’s name. And take it from me, the locals here hate it. In fact, irritation with this faux pas hit such heights that a social media campaign was started a year ago called “It’s Colombia, NOT Columbia.” Its remit is to oust perpetrators of this crime and make an example of them.

Those left with heads hanging in shame include Starbucks, NBC Weather, UK newspaper The Metro, and the normally factually-flawless Paris Hilton. As a believer in taking the law into your own hands, I’d like to name and shame Wales Online for their article “Catherine Zeta Jones to Play Columbian Drug Queen in Film,” published in October 2014. At least this publication used the correct vowel seven out of eleven times in the article…

5. It’s full of gun-slinging drug dealers high on cocaine.

When visiting a country, most of us like to follow the local customs. In England you drink pints of beer in the pub. In Scotland you savor some of the finest whiskey in the world, and in Colombia you snort cocaine. Yet while England’s penchant for public houses and Scotland’s for scotch have a certain ring of truth, Colombia’s addiction to white party powder is simply not.

Yes, the drug is cultivated in and trafficked from Colombia, but consumption among residents is incredibly low in comparison to other countries. Not only do the tea-swilling English like to snort more, but the Scots were named as the biggest cocaine users in the world by a UN Drug Report. Colombia, meanwhile, appears way down on the list, behind both the US and the prim and proper Swiss.

6. You have to travel everywhere on a bus.

While traveling on buses in many South American countries might be the best option due to expensive flights, Colombia is different. Admittedly, some journeys are worth a pelvis-thumping bus journey, especially around the coffee region where dramatic valleys and deep green mountainsides make for perfect photo opportunities. But for those who’d like to get to their destination in a reasonable time, local airlines (especially budget option Viva Colombia) offer cheap deals that are often less expensive than buses.

7. When Colombians are not taking cocaine, they’re swigging coffee.

Colombia may produce a bucket load of coffee, but they tend not to get high on their own supply. Despite working long hours, most Colombians don’t rely on a cup of Joe for that early morning pick-me-up. That’s not to say they don’t drink coffee, they just don’t drink it to the extent you would think of a country that grows some of the best beans in the world.

The truth is that most Colombian coffee beans are exported to the US and coffee-crazed European countries. Studies into coffee consumption show that Colombians drink less coffee per capita than the US and most European nations — especially the Nordic countries. The phenomenon twists even more bizarrely when you consider that Colombia also imports coffee, mainly from Peru and Ecuador, due to lower prices.

8. Everybody knows Pablo Escobar.

I once asked a group of Colombian friends to name five things you should never say to a Colombian at a party. High on everyone’s list was, “Don’t ask if I know Pablo Escobar.” The drug lord who once terrorized parts of the country with his drug cartel cronies was gunned down in 1993, and the nation has spent two decades trying to forget him. Tourists wanting to hear stories of his drug-trafficking antics will be left disappointed. Those who persist with unwanted questions are likely to be ignored, insulted, or in the worst case scenario, told to get out of Colombia and never come back.

Insider's Guide to Whistler: Ep. 5

Watch this 5-video series in which adventurer, travel writer, and TV host Robin Esrock joins infamous Whistler Insider Feet Banks for a whirlwind tour of the best that Whistler has to offer.

WHISTLER AND FAMILIES go hand in hand. Our intrepid guides gather up their respective families, tour the kid-friendly activities and dining spots, and dish out some helpful tips for the perfect family vacation at Whistler.

* * *

This video is proudly produced in partnership with our friends at Tourism Whistler. Visit their site to watch the entire Insider’s Guide to Whistler series.

Travel made me a better white person

Image by Ricardo Liberato

WHEN I FIRST STARTED TRAVELING, I wasn’t aware of my race. Not in an “I don’t have a race!” type way, but in the same way I thought about accents. That guy has a southern accent. That girl has a Scottish accent. That guy is from Minnesota. My accent? Well, I don’t have an accent, I’m the one who’s normal. It’s the type of thinking that doesn’t stand up to a second’s worth of scrutiny, but it’s been standing for decades because it’s not given any scrutiny at all.

This is a fairly normal default stance for white people such as myself. None of this is to say we’re evil, ignorant people, it’s just to say we live in a society where people rarely draw our attention to our own race. So when I started traveling, I wasn’t white, I was normal.

Traveling in the non-white world

When I started traveling to places that weren’t predominantly white European, I started noticing something: I had nicknames. In South America, I was a yanqui. In Hawaii, I was a haole. In Japan, I was a gaijin.

It’s not like I’d never been called names before. Outside of the US, I’ve been called a wanker, a cabrón, a cunt, a poofter, and a shite. Those names I can generally brush off, though, because they’re insults that refer to something I did that was probably in my control. The new nicknames, however, I wasn’t used to. I’ve been called an “American” or an “Ohioan” plenty of times, but these new nicknames weren’t all that concerned in where I was coming from, they were more concerned with what I was born looking like. For the first time, a label was attached to me that I was mildly uncomfortable with, and that I could do nothing about.

As I traveled more, I found that the labels, once I started to get to know someone, got checked at the door. But they were still the starting point for all conversations. I had one guy in Argentina who straight up would not believe that I voted against Bush. A rickshaw driver in India was upset that I was anti-Muslim, simply because I said I was American. For once, there were negative connotations attached to other people’s labels of me.

“Shit,” I remember thinking, “This kind of sucks.”

Chinese vs White Dominance

My next lesson was in going to China. In China, most of the political and cultural life is dominated by the largest ethnic group, the Han Chinese. The Han make up about 92% of China’s population, but there are dozens of other major ethnic groups in China. The ones I came into the closest contact with were the Tibetans.

The world is pretty familiar with the fight for Tibetan independence. What the world is less familiar with is the fact that it’s not just a religious struggle, it’s an ethnic one as well. Tibetans are discriminated against in some very blatant ways, and in some very subtle ways as well.

Touring around Tibet, I was shocked to see this. The Han that I talked to thought they were being generous to the Tibetans by introducing them into a flourishing economy and by ending the rule of the at times regressive Lama system. But how could one ethnic group be so dominant over the others without being aware of it? How could they skew the system so clearly against a group that was supposedly a part of their own country? How could they marginalize and criminalize an entire culture without seeing what they were really doing?

I felt self-righteous about it for a few days, and then I went home to the United States. “Ohhhh,” I thought. “Right.”

Travel isn’t fatal to bigotry and prejudice.

There’s a famous Mark Twain quote, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” It’s not totally true. I know plenty of people who have traveled extensively and who have still come home holding prejudices against people of other cultures and backgrounds. But travel does make it harder to be prejudiced and ignorant of your prejudice. It’s an overused word in discussions today, but travel, more than anything else, makes you aware of your privilege.

Travel made me aware of how lucky I am to be white, and how much the culture I’ve grown up in has been built to benefit people who look like me, often at the exclusion of others. It made me aware that I can only see from where I stand. And it introduced me to people who stand elsewhere. And understanding my privilege has put me on the road to becoming a slightly better white person.

Why traveling is hard for introverts

Image by Lulu Lovering

1. Getting to know someone romantically, and then being called “intense.”

If you’re like me, getting to know someone on a romantic level takes a good amount of work. My feelings and life aren’t all out there in the first conversation; rather, things tend to be revealed as time goes on. I also have no problem sitting in silence for long periods of times, especially on road trips or in transit, which perhaps leads to being labeled “intense,” as I’ve been told many times by men. It happened to me once in Ireland, and then the man followed up with something like, “these long silences with nothing to talk about.”

I was stunned. For me the silences weren’t uncomfortable; they were blissful. I really didn’t realize that someone else would see it differently.

2. Asking someone for directions when you’re lost.

On Lesbos island in Greece, Lena (my German WWOOFing counterpart) and I got hopelessly lost when trying to return our rental car to its office. We saw a taverna filled with people, and since Lena was driving, she urged me to go in and ask for directions. My heart immediately flip-flopped. I got out of the car, entered the taverna, and asked a random table of people how to get to the main street of Mytilini. Of course, hardly anybody spoke English, and I stood there babbling and embarrassed until a cook emerged from the back of the building and told me what to do. A part of it has to do with not wanting to bother anybody; another part of it has to do with the terror of simply starting a conversation with someone.

3. Approaching that table of travellers already having a really good time.

On my first night in Athens I went to the rooftop common area of my hostel and perched on a stool at the bar like a bird about to take flight. I wanted company, and conversation, but everyone around me already seemed to be doing quite well with it. I figured a pint of Mythos would help loosen my tongue, but it was actually Anna, the Finnish bartender, who first engaged me in conversation. When an introvert is in the mood to meet people, sometimes just showing up is all you can do.

4. Staying in a hostel, or Couchsurfing.

Even if you’ve got a private room booked at a hostel, at some point you’re gonna have to be around people. Or you’ll be privy to the shenanigans of other guests, or you’ll be frustrated by the noise in the kitchen when all you want to do is cook a pack of ramen noodles but those dudes playing beer pong just won’t go away. Couchsurfing is a whole different ballgame. You’re literally occupying space in someone’s home, for FREE. You owe it to your hosts to be friendly and conversational, and switched on. And for introverts, that’s not always available on demand. You’d be missing out, however, if you didn’t try it a few times.

More like this: How to piss off an introvert

5. Dealing with EVERYBODY ELSE on a group tour.

If you’re an introvert, group travel is probably not for you. On the other hand, if you have trouble meeting new people thanks to your introversion ways, group tours are a godsend. Finding a balance? Necessary. I once did a Contiki tour through Prague, Budapest, and Vienna. The group I travelled with was overwhelmingly outgoing — there was a group of YouTubers who spent one afternoon filming a chase scene through Budapest’s busy downtown core. I loved those people and their entertaining ways, but I requested a private room so I could have the downtime when I needed it.

6. Striking up a conversation with a stranger.

Perhaps the single most terrifying thing about travelling as an introvert is just putting yourself out there. When you actually want to, that is. Even introverts get lonely every now and then. I remember watching amazed as my friend approached a sketch artist at a café in Reykjavik, Iceland. The two struck up a conversation about art and music, and the Icelander eventually ended up at our accommodation for a guitar session. I was grateful for my friend’s boldness; without him, the relationship with a local would never have happened.

7. Finding that downtime after you’ve been socializing all day.

If you’re out sightseeing and exploring, chances are other people have surrounded you for most of the day (unless you’re on a trail somewhere, and even then…). I will often book a hotel room for a night or two when I’m travelling, no matter how extravagant the purchase may seem on a budget. There are few things more comforting to an introvert than spending an evening locked into a cozy hotel room, watching television or reading or binge eating on Doritos and local pastries. The key is to give yourself a day or two during a whirlwind trip to do so, otherwise burn-out is imminent.

8. Being avoided by people (or told you’re unapproachable) because you’re lost in thought.

I’ve been told that when I’m lost in thought or concentrating really hard on something, I look like the least approachable person in the world. My eyebrows furrow; the crease between my eyes deepens. Every time I’m in yoga class and my instructor tells us to relax our jaws and our faces, I’m surprised by how tensed up I really am. Introverts don’t tend to think about how their body language is perceived by others — we get lost in moments instead.

More like this: It's ok to be an introvert, really

9. Getting to know what the local nightlife is really all about.

As I prepare for my 2015 move to Berlin, my friends all tell me that the nightlife is amazing, that the music scene is fab, and that the 48-hour nightclubs are ridiculous and a “must do.” While I love nightlife and consider it essential to a travel experience, the thought of a 48-hour nightclub is only good in theory. I’d last maybe 20 minutes in such a place before a younger person jostles me just hard enough to make my rage bubble over. I’d rather sit at a quiet pub and nurse a Guinness, thank you.

10. Being on a crowded subway train, or a bus, or flight.

Some introverts will literally do anything to avoid crowded public transit. I am one of those people. I have not used the public bus in my hometown of St. John’s for over five years. I used the subway system in Montreal just ONCE the whole time I lived there. The thought of being pressed against so many bodies inside a tiny train car makes my palms sweat. The plus side: I walk everywhere. And that matters when your ideal vacation is eating nothing but halva the entire time you’re in Greece.

8 lies about moving to London

Image by Darrell Berry

1. I’ll take on a sexy British accent just by listening to locals.

Except the locals are not only British, but also Somali, Indian, Chinese, or any of a plethora of ethnicities represented in London. Take a walk down Empire Way near Wembley Stadium and you’ll hear Farsi, Punjabi, Mandarin, and Bengali among just a few languages. So have fun picking up that British accent, considering a significant chunk of what you hear will be not British.

2. I’m never going to spend a weekend in.

This philosophy makes sense when you are a traveler staying in Westminster and time is not on your side. But with a teaching job at TimePlan, fellow teachers to grab a pint with, and adult responsibilities, London becomes less of a trip and more of a home. Just because there is so much to see and do does not mean it needs to be seen and done all at once. Plus your Saturdays in, spent eating PB & Js and binge-watching Doctor Who, help make the weekends out at the Rooftop Film Club and the Handmade Burger Company all the more enjoyable and affordable.

3. Getting around will be quick and easy with public transport.

The tube itself is quite good, if unreliable. If you can catch the Metropolitan line directly to your work in King’s Cross during peak hours and also manage to get a standing spot that doesn’t involve your neighbor’s armpit and a briefcase on your backside, you are in luck. Unless, of course, there is planned work, a delay, or a malfunction.

More like this 11 idioms only Brits understand

Try to alight at Oxford Circus in the heat of summer despite the surge of oncoming passengers. A commute from Wembley Park to Brookland Junior School is only 14 minutes by car, but will take over an hour by bus. Plan for at least two people to chase bus 83 or 182 and make it wait at each stop. Make sure to sit between the man eating a nauseating sandwich and the screaming child just for kicks. Cancel any and all plans on the opposite side of the Thames unless they are worth at least 2 hours of travel.

4. I speak English. The Brits speak English. There’s no difference.

Except you spell every other word incorrectly according to British English. You’ll constantly forget to add a “u” to color and mold, and you’ll switch the “er” in center, liter, and meter. Don’t be annoyed by the overuse of “brilliant,” “cheers,” and “rubbish” as part of everyday vocabulary, and make sure not to comment on your neighbor’s pants, or she may blush. You will learn to interpret body language over words, because you will never be told straight up that you’re a jerk or your ideas suck, since “That’s interesting” will suffice.

5. That studio’s a little small but it’s homey!

Small is the biggest possible overstatement in regards to housing in London. Better adjectives would be cramped, miniscule, or diminutive. Your bed will serve as your sleeping quarters, sofa, dinner table, and storage unit simultaneously. Don’t forget to smile gracefully when reminded you are privileged to be paying a mere £950 per month for a 32-square-meter asylum with white walls and burnt orange doll-sized cupboards in Wembley. Look on the bright side, since there are no candles, nails, tape, pets, or plants allowed, you don’t have to worry about any extra money spent on frivolous decorations.

6. Everyone’s going to know I just moved here.

Nobody will notice or care. They are too busy heading to Canary Wharf, reading the London Evening Standard, sipping a Costa coffee, or chatting with friends. Chances are they were newcomers too just last week, last month, or last year. With a constant stream of new arrivals, it is near impossible to tell if people have lived in London their whole life or just arrived yesterday. So revel in your anonymity because nobody cares about your arrival date.

7. I’m only going to eat fish and chips and meat pies.

You can eat shepherd’s pies at Piebury Corner and fish and chips at The Codfather to your heart’s delight, but rest assured there are also other options available. From Polish croissants to Bombay spiced snack mix, the grocery is full of offerings to suit every palate. Asda even has an American food section devoted solely to Gatorade, Pringles, and Snickers.

If you are craving specifics such as Twizzlers, bottled mustard, or tortilla chips you may be out of luck. However, the majority of food does not have processed chemicals or unpronounceable words in the ingredients, since the government seems to care about what the population is ingesting.

8. I’m going to be broke.

If you party every weekend at Fabric and eat out at the London Designer Outlet every night then yes, you will go bankrupt. Still, you don’t have to eat digestives for every meal to survive on a budget. A week’s worth of staples such as broccoli, ground beef, and rice for two at Lidl can cost less than a single meal out at Nando’s.

For entertainment, the National History Museum, Royal Air Force Museum, and many others in the city are free, providing endless options including exhibitions on the average London woman, science experiments on crowd movements, WWI poppy memorials, and new theatre pieces at the Battersea Arts Centre. Even when you need a fix, you can still save money by choosing Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen over Wagamama, yard tickets at the Globe over a ticket to Cineworld, and a 4-pack of Strongbow from Tesco over a beer at Hobgoblin.

8 stunning natural areas in Arizona

Image by Nate Merrill

Image by Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarren

Image by Ken Bosma

In the Santa Rita Mountains, just 25 miles south of Tucson, the cool refuge of Madera Canyon also happens to be one of the best birdwatching areas in the U.S. The forested microclimate is a perfect habitat for spotting the elegant trogon — males are especially distinctive with their metallic green and red-orange feathers. And under the green canopy roam javelinas, deer, turkeys, and mountain lions. Even the occasional jaguar has been photographed here. Coatimundi, the raccoon relative common in the jungles of Guatemala, make Madera Canyon their home as well.

Climb above the canyon if you feel up to a 10-mile hike, and you’ll end up on the peak of Mount Wrightson. At 9,452 feet, this is the highest point between Tucson and the border, and the 360-degree views from the summit are stunning, stretching all the way to Mexico.

2. Horseshoe Bend and Antelope Canyon

Image by ANDR3W A

Image by Manop

Image by John Fowler

You’ve likely seen pictures, but you might not know their names or where to find these special places. Near the Grand Canyon but far from its crowds, the Colorado Plateau offers plenty of quiet red rock scenery. Horseshoe Bend, an easy hike from Highway 89 just south of the town of Page, may be one of the most photographed spots on the Colorado River. But if you come midweek, you can find solitude above this spectacular gorge. Colorado River Discovery offers half-day raft trips down on the water as well.

Nearby is the surreal Antelope Canyon. To see the legendary shafts of light among undulating ribbons of sandstone, you have to come here between spring and fall, and you must go with a Navajo guide; this is sacred land, and during sudden summer storms the narrow chasms can quickly become deadly.

These may be among the most photographed geological formations in the Southwest, but they’re surprisingly accessible, and nothing compares to being inside the landscape itself, in person, surrounded by the miracles of erosion and light.

3. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area

Image by Daina Dajevskis

Image by Kristy Hom

Image by Bureau of Land Management

Running northward from the Mexican border to just south of I-10, the San Pedro River is one of the last remaining free-flowing rivers in the Desert Southwest. Lined for some 40 miles with towering cottonwoods rising from semi-arid grassland, the region is a life-sustaining flight path for migrating birds, and over 370 species have been spotted in the area.

Humans have inhabited this fragile landscape for millennia — excavations at the Murray Springs Clovis Site have produced prehistoric spears and mammoth bones. Nearby, hike to the ruins of Presidio de Santa Cruz de Terrenate, an 18th-century outpost of the Spanish Empire.

A few miles east of the town of Sierra Vista, the San Pedro House is a good starting point to explore this unique ecosystem. A bookstore and information center will get you going, whether you’ll be hiking, biking, or looking up with binoculars.

4. Southern Arizona’s sky islands

Image by Ken Bosma

Image by Andrew

Image by Donna Sutton

A larger region that encompasses many other entries on this list, Arizona’s sky islands are a series of mountain chains in the southeast of the state, isolated from one another by stretches of arid lowlands, rising like forested islands from the surrounding ‘seas’ of Sonoran Desert.

The Santa Catalinas are among the most prominent and comprise one of the most ecologically diverse spots in the country. Driving from Tucson up into these mountains is like traveling from Mexico to Canada — in less than an hour. As you climb from 2,500 to 9,000+ feet, you’ll make your way from towering saguaros through grassland, junipers, oaks, and pines, finally arriving at the mixed forest of aspens and Douglas firs surrounding Mount Lemmon Ski Valley — the southernmost ski resort in the U.S. It’ll also be a welcome 30 degrees cooler at the summit.

In the state’s extreme southeast corner are the Chiricahua Mountains — one of the last strongholds of the Apaches and a wonderland of pillars and zoomorphic rock formations rising through the evergreens. These higher elevations are still havens for mountain lions and bears, perfectly at home above the sun-baked lower expanses. Aside from the Santa Catalinas and the Chiricahuas, you can hike the Huachucas, the Pinaleños, the Peloncillos, the Santa Ritas, the Baboquivaris, and the Tumacácori Highlands, all within a few hours’ drive of Tucson and Sierra Vista.

5. Ponderosa pine forests near Flagstaff

Image by Nicholas A. Tonnelli

Image by Coconino National Forest

Image by John

To the southeast of the Grand Canyon, the region around Flagstaff is home to one of the largest ponderosa pine forests in the world. Stretching from the Colorado Plateau along the Mogollon Rim to the New Mexico border, these stately pines cover tens of thousands of acres.

Rising above the forest are Arizona’s highest mountains — the volcanic San Francisco Peaks. Summer and fall offer endless hikes; one of the best is the climb up Humphreys Peak. At over 12,600 feet, this is the highest point in the state. In winter and early spring, there are 40 runs to choose from at the Arizona Snowbowl alpine resort. And just west of town, Flagstaff Nordic Center is the place to go for cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and snowbiking (think a pair of skis attached to a bike, and you’re on the right track).

This is high country, ranging from 6,000 to over 12,000 feet above sea level, so give yourself time to acclimatize to the lower oxygen levels.

6. Saguaro National Park

Image by Dave Bezaire & Susi Havens

Image by Geoff Stearns

Image by Photography Peter101

Tucson is flanked on its western and eastern edges by Saguaro National Park, showcasing the giant cacti native only to the Sonoran Desert. With a lifespan of up to two centuries, Saguaro can reach the height of a six-story building and grow as many as two dozen arms.

Compared to its more famous Arizonan cousin, the Grand Canyon — which receives 7 times as many visitors — Saguaro is relatively quiet. Hiking, trail running, and horseback riding are popular in both divisions of the park, but you can also drive the leisurely loop roads if you want to see the cactus forests from the comfort of your car.

The park’s western division sprawls over the Tucson Mountains — the sunsets are spectacular and you can even get up close to pre-Columbian petroglyphs carved by the Hohokam people. When the spring rains are right, wildflowers blanket the slopes. In the eastern division, trails lead up from the saguaros into pine forests on the 8,000-foot summits. And in the annual Labor Day race, 1,000 runners gather before sunrise to beat the heat on an 8-mile loop road in the foothills of the Rincon Mountains.

7. Ramsey Canyon in the Huachuca Mountains

Image by Clay Gilliland

Image by Clay Gilliland

Image by Jeff Hart

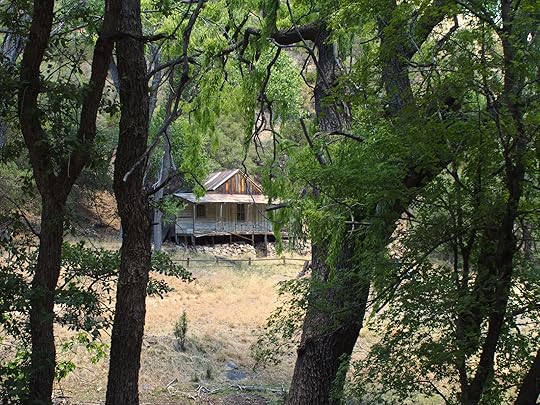

In the heart of the Huachuca Mountains, find homesteaders’ cabins and apple trees as you hike among deer and wild turkeys in this Nature Conservancy preserve just north of the border with Mexico. Chihuahua pines and agave share the microclimate with cottonwoods, sycamores, and even maples; autumn here is a brilliant show reminiscent of the Appalachians thousands of miles away. Spring through fall, guided hikes that focus on the region’s birds (including 15 hummingbird species) are led by the Ramsey Canyon Preserve.

Black bears are common at Ramsey Canyon, so guides recommend you don’t pack food with you. Come early in the day or midweek, since there are only a couple dozen parking spaces at the preserve’s entrance — first come, first served.

8. Joshua tree forest between Wikieup and Wickenburg

Image by Sarah Nichols

Image by Amarins Sandaw

Image by Gabriel Radley

Except for the anthropomorphic arms of the saguaro, perhaps no other botanical profile is as emblematic of America’s Desert Southwest as this giant spiky yucca. In western Arizona, the Mojave and Sonoran desert ecosystems converge, and for 50+ miles along US 93, between the towns of Wikieup and Wickenburg, you can drive the Joshua Forest Scenic Road surrounded by hundreds of these enigmatic plants.

The heritage of mining prospectors and ranchers is alive and well along this highway. Driving through, you might spot a rodeo in Wickenburg; you might even want to stay and become part of the scene at the Flying E dude ranch. Among the valleys, mountains, and rolling hills, temperatures can go from well below freezing in winter to well over 120 degrees in the summer.

Even though this is the main highway between Las Vegas and Phoenix, gas stations are few and far between, so always travel with plenty of water. You’re in the heart of the Southwest, after all.

This post is proudly produced in partnership with the Arizona Office of Tourism. Visit their site and start planning your Arizona adventure today.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers