Matador Network's Blog, page 2189

November 4, 2014

Growing up in Newfoundland

Photo: jon hayes

1. Simultaneously hating and loving squid hats

These hats got popular when I was in junior high sometime, and I’ve never quite figured out why. I didn’t wear one, at any rate. A squid hat was made from multicolored fleece material, and the top sprouted long tentacle-like pieces of fabric…hence the “squid” name. They became immensely popular for a few years and then died out altogether. Thankfully.

2. Those days when we used to drive across the frozen bay in our trucks

I remember watching the headlights speed across the frozen expanse of bay separating Conne River from St. Alban’s on the south-central coast. Every now and then you’d hear about a snowmobile crashing through the ice, or some other related accident, and yet it never really discouraged anyone. Last year was the first time I’ve seen the bay freeze over since I was a kid. What compels someone to drive a Ford F-150 truck across potentially weak ice, I don’t know.

3. Those outrageously tacky foiled Christmas decorations

You know, the kind of decorations Nan would string from the ceiling in criss-cross patterns and tucked into corners. If you don’t know, refer to Simani’s mummer video. When I think about those decorations, I picture my relatives standing around with t-shirts tucked into jeans, cradling tumblers of rum and coke. And it always makes me homesick, without fail.

4. The Samantha Walsh tragedy

Samantha Walsh’s disappearance and subsequent murder was a significant turning point in my young life. I don’t like to think I was naïve; I’d grown up reading about everything from the Holocaust to the Beothuk genocide. But I remember being glued to the CBC news reports about Samantha Walsh’s story, because she was my age and because I couldn’t fathom how something like that could happen in quiet little Newfoundland. How wrong I was.

5. Nan’s cooking

Oh, how I miss those days when I’d awaken to the smell of baking banana bread or a pot of Jiggs dinner on the stove. I’d end up at my grandmother’s (Nan’s) house several times a week for a plate of chocolate coconut balls or some lemon-meringue pie. It’s not that those things aren’t around anymore, but there’s something about her cooking that can’t be replicated. Like many Newfoundlanders, my grandmother raised 12 children and worked harder than most professionals I know. Maybe that love made everything taste better.

And on that note:

6. Growing up with an insanely large extended family

Newfoundlanders like to copulate. Both of my parents have 12 brothers and sisters, and those 24 aunts and uncles of mine are mostly married with kids. I have over 20 first cousins — never mind the seconds and thirds. Can you imagine what family get-togethers are like? Chaos. Pure, glorious chaos.

The best part is that I’m actually quite close with them all. Cousins are like sisters. I, on the other hand, only have one brother…and most of my friends come from families with three siblings or less. I kinda feel bad for my own hypothetical kids who won’t grow up knowing what it’s like to have to question whether or not you might be related to everyone in town.

7. Having to rinse our mouths with fluoride in the mornings at school

I’m not sure who thought this was a good idea. We’d all stand dutifully by our desks, tear open a packet of fluoride, swish the foul substance around in our mouths for awhile, and then spit it all back into the packet. What in the heck.

8. For those of us in rural Newfoundland, making Christmas wish lists by Sears catalogue

Picking up the Sears catalogue sometime in mid-August or early September was pretty much the highlight of my young materialistic life. Growing up with NO other shops or brands around (other than that stifling styrofoam interior at Riff’s), we had the sole shopping option of Sears. And, boy, those pages chock-full with toys and potential entertainment were like the Holy Grail.

9. Your first beer: drinking in “the pit” or in someone’s “shack”

A lot of my mainlander friends are stunned to hear I had my first beer at age 13. I turned out okay, right? I grew up in rural Newfoundland, away from all the entertainment of the “big city” (St. John’s), and so there wasn’t much to do other than seek thrills from a beer bottle. My guy friends had built a shack in the woods where we gathered many weekends until the night it burned down. Our other option was “the pit,” literally a hole in a gravel pit that shielded us from the police.

My friends from St. John’s also started early but tended to gather in empty parks or sports fields. Whatever worked.

10. When dial-up internet was introduced and you spent all your time at the public library

When the internet first arrived to my town, it was dial-up, and we had a limit of 15 hours per week. The public library, however, had six computers with unlimited access (in 30-minute slots). My friends and I would log onto chat rooms and forums, trying to connect with other teens across the province. Once, I talked to a girl in Grand Bank who knew my pen pal, Raylene. She ran off to snag Raylene from her home, and we ended up chatting online for hours. That actually happened.

11. Not actually appreciating Newfoundland until much, much later

I was never much happy with growing up in Newfoundland. I hated my isolated upbringing, and traditional Jiggs dinner, and the ol’ crooning of Irish/Newfoundland singers wailing over accordions and fiddles. At some point it all clicks for us: this delightfully absurd island is different from everywhere else, and why on earth would we want it to change?

Insider's Guide to Whistler: Ep. 4

A 5-video series in which adventurer, travel writer, and TV host Robin Esrock joins infamous Whistler Insider Feet Banks for a whirlwind tour of the best that Whistler has to offer.

NO TOUR OF WHISTLER is complete without ducking into the Village’s best hot spots. Feet and Robin tick off the highlights and take time, of course, for some après action.

* * *

This video is proudly produced in partnership with our friends at Tourism Whistler. Visit their site to watch the entire Insider’s Guide to Whistler series.

Feature photo: Derek Purdy

November 3, 2014

A traveler’s guide to synchronicity

Photo: Lillian Vasquez

What is Synchronicity?

In the 1920s, Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung coined the term ‘Synchronicity’ to point to the meaningful interactions of events / objects and the internal states of the mind. Synchronistic events, he theorized, are the mysterious interactions of the psyche (our mind, thoughts) and the outside world, and speak to a far richer reality than we may suppose. Synchronistic events are not described causally; our internal states of mind don’t cause events to occur in outside reality. Synchs are described meaningfully — they are the interplay of personal meaning and the external world of occurrence.

This mysterious phenomenon of consciousness occurs rarely for some and as a matter of regularity for others. For the majority of people who describe synchronistic events, it is an overwhelmingly meaningful experience.

In September of 2014 I attended The Synchronicity Symposium, held in Joshua Tree. The ‘lessons’ I present here are based on the various lectures and workshops and insights I teased out when reflecting on how some of Synchronicity related back to my travels.

“All the events in a man’s life stand in two fundamentally different kinds of connection: firstly, in the objective, causal connection of the natural process; secondly, in a subjective connection which exists only in relation to the individual who experiences it, and which is thus as subjective as his own dreams.” — C.G. Jung

“Synchronicity reveals the meaningful connections between the subjective and objective world.” — C.G. Jung

Lesson 1: Act and a way will (usually) open.

It requires innumerable and subtle acts of coincidence to exit a city like Los Angeles.

I begin to realize this as I wedge my dust-streaked car into the column of morning traffic and point myself towards the San Gabriel mountains and the desert and Joshua Tree. To pack my bags and plot my course with the intention of escaping LA is an unconscious act of faith that the Powers That Be (God, chaos, nature, karma, the flying spaghetti monster — pick one) will even allow such a journey to take place. Yet everyday I walk out the door with a certain unconscious confidence.

A million unforeseeable obstacles could sideswipe my journey — I could wake up with Ebola, get a flat tire, win the lottery, or be arrested under false charges of impersonating a police officer. I could be run off the road, have a brain aneurysm, have my cat go missing, have an existential breakdown, or I could simply change my mind and decide to drive in the opposite direction.

Anything could happen.

A host of forces, many blind and chaotic, need to conspire in my favor to undertake any journey, however humble. But notice how often we are allowed to slip into our little schemes without being diverted or squashed like a bug? I believe when we act with intention (i.e. step out of the house, into the world ) it sends a ripple of coincidences out that opens a way for our little plots and schemes. To be more available to synchronistic events, we must answer the Call to Adventure and go forth into the world with intention. We must act.

We must place our bodies and our minds in the world and see what happens.

Lesson 2: Synchronicity clusters at important events (including travel).

Jung suggested that the phenomenon of synchronicity seems to cluster around impactful, transformative, and important events. In his talk entitled ‘Varieties of Synchronistic Experiences’, author, professor and cultural historian Richard Tarnas echoed this point and invited his listeners to pay special attention at times of birth, death, and transformation. I believe that synchronicity also clusters around the travel experience.

A journey abroad is often a transformative experience, at least I have found this to be the case.

I believe the transformative power of travel can be found in the moments where the contents of the soul are challenged and expanded by the contents of the world. A symbolic, self-transformative chord is struck where one might feel for a moment that the universe is working in one’s favor and that perspective is lifted from its usual narrow confusion to glimpse a state of grace.

My first travel experience at the tender age of 20 was a whole course in synchronicity. I had some different ideas back then — I was kinda sorta homophobic and unabashedly ultra conservative. I was a nice guy, just a little ignorant. By turns, travel forced me to question and ultimately destroy so many of the ideologies I had come to identify with.

Sitting alone at a dining room table in a hostel, my first night abroad on a 3-month walkabout across Italy, I am befriended by a lesbian couple who take me under their wing for 3 days of exploration around Lago di Como. Before that, the phrase ‘my lesbian friends’ had never passed my lips. Next I was introduced to, and traveled a stretch with, a socialist from Berlin who politely challenged my neo-con prerogative until I had to concede to myself that although I wasn’t a socialist I could no longer defend many of my previously held positions.

This was the synchronistic medicine of travel — to find underdeveloped points in my ego and psyche and put people in my path that would directly challenge them and create a new perspective with which to view the world.

It was stated several times at the Symposium that synchronistic events are often experienced around these certain periods such as birth and death. My travels through Italy were a journey of healing after the passing of my father. It seems that I was primed for synchronicities — pried open by the vacuous force of death and available for rapid transformation.

Lesson 3: Nothing stops moving.

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “You cannot step twice into the same river.” I think that insight applies everywhere; you also can’t visit the same cafe, street, borough, or country twice. Everything has shifted in subtle and sometimes enormous ways. Just as the river is in continuous flux and is therefore essentially impermanent in nature, so is the rest of life — including us as individuals. You aren’t the same person you were 10 years or even 10 minutes ago. Nothing stops moving. This means that new experiences, new perspectives, and new opportunities for synchrony are always opening up to us.

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “You cannot step twice into the same river.” I think that insight applies everywhere; you also can’t visit the same cafe, street, borough, or country twice. Everything has shifted in subtle and sometimes enormous ways. Just as the river is in continuous flux and is therefore essentially impermanent in nature, so is the rest of life — including us as individuals. You aren’t the same person you were 10 years or even 10 minutes ago. Nothing stops moving. This means that new experiences, new perspectives, and new opportunities for synchrony are always opening up to us.

For travelers this goes double.

Sometimes it feels like the earth is whipping past under your feet. Sometimes it feels like each pregnant moment dies before it reaches you to give way to the next. Since nothing is fixed, you know that every circumstance is pregnant with the next — that life requires constant improvisation and adaptation. Those that embrace and take advantage of this constant flux get in The Flow. Flow requires a liquidity of movement and thought, like a river finding the path to the sea. I believe that people that experience a lot of Flow are more open to synchronicity and meaningful coincidences. They don’t fight the current, they ride it. They see where the flow is moving and respond in kind. Flow is the difference between being swept downstream and riding the current.

Lesson 4: Pay attention

“Synchronicity is an ever present reality for those who have eyes to see.” — C.G Jung

When describing his theory of the human mind existing as an immaterial ‘field’ of consciousness, Symposium keynote speaker Rupert Sheldrake points out that the Latin root for the word “attention” is attendere, which means “to stretch towards.” He suggests that when paying attention there is a literal stretching / expanding of consciousness towards that which is perceived and attended to by the mind.

Other speakers also stressed the need to pay attention, to watch the world and yourself, and to especially attend to relationships, dreams, and synchronicity. Inattention will keep the deeper meanings and possible new perspectives at bay. Thankfully, many methods for gaining and keeping attention are widely available: meditation, writing, mountain climbing, painting, yoga, and many others. I like people watching for honing my attention — sitting with a coffee and seeing what I can see while also watching my watcher — seeing where the unfolding scene takes my mind.

As travelers we have a lot to pay attention to.

As travel writers, photographers, and filmmakers we have even more to pay attention to. At times it seems that there is too damn much to pay attention to. It is then that the quality of our attention counts most. A practiced mind can hold a higher quality attention than an unpracticed one. This is what we refer to when we speak of a photographers ‘eye’, not only their skill with a camera but also their skillful use of attention.

To develop an ‘eye’ is an art the traveler has many occasions to develop. This eye can be for photography, illuminating humanity through narrative for gaining self knowledge. At any turn of the road a traveler has new needs of his attention and new opportunities to further develop it.

Lesson 5: Individual experience matters most.

“Synchronicity means the simultaneous occurrence of a certain psychic state with one or more external events which appear as meaningful parallels to the momentary subjective state…” — C.G. Jung

In his session entitled ‘The Quest for Gnosis’, author and theological scholar Gabriel D. Roberts stressed a point that resonates with me deeply as a traveler — intrinsic, experiential knowledge is the most valuable form of knowledge we possess, and should be sought out constantly. I would go further and say firsthand, experience-built knowledge is the only knowledge worth a damn. Gnosis usually denotes a ‘spiritual’ knowledge, but I tend to think of it more broadly as self knowledge. It is knowledge built on experience, on reflection.

Travel and self knowledge go hand in hand.

Nobody can tell you what you learned from travel, how you grew or were challenged, or what synchronistic moments you experienced. Only you know. It is at its root a supremely individual experience. By relying on this type of personal experience, we are also accepting personal responsibility for our knowledge or lack thereof. We are responsible for finding, creating, and engaging the ‘important’ experiences that give us firsthand knowledge of the world. Travel can give the raw data, the raw potential for growth and synchronicity, but we have to take responsibility for meeting it head on.

It is only in the arena of individual experience that synchronicity can take place.

Lesson 6: Find the gifts of exile.

Travel can be a type of self-imposed exile. We may banish ourselves into the world to try find our way back anew. Far from the familiarity of culture and kin, a certain stoic loneliness can set in as the exile unfolds. It is here that you meet yourself away from your routines and habitual personas, and see what you are away from the things that had helped defined you.

Travel can be a type of self-imposed exile. We may banish ourselves into the world to try find our way back anew. Far from the familiarity of culture and kin, a certain stoic loneliness can set in as the exile unfolds. It is here that you meet yourself away from your routines and habitual personas, and see what you are away from the things that had helped defined you.

This is the gift of exile — the medicine of self knowledge.

Dreamworker and artist Toko-Pa illuminated this beautifully at the Synchronicity Symposium:

“Every heroic myth will see to it that the hero or heroine must endure a period of her own exile. It’s only then, when the way home is completely lost, that she comes into contact with the true medicine of her calling.”

She is harkening to an important principle in the Hero’s Journey — Joseph Campbell’s mythic story structure. The Hero, facing difficulty and exile, finds her true calling. In the myths, this true calling is in service to her community and enriching to the world. This healing gift of exile is referred to by Campbell as “the elixir.”

Synchronistic events may help point to the gifts of exile. I found that hidden contents of my psyche are made manifest and challenged during the self-imposed exile of travel — providing me the essential gift of self knowledge and the opportunity to face myself, by myself. Often times, synchronistic events can usher in the gifts of exile through encounters with people, ideas, and new perspectives.

Lesson 7: Avail yourself.

Avail has two meanings:

1. Use or take advantage of (an opportunity or available resource). “Josh did not avail himself of my advice.”

2. Help or benefit. “No amount of struggle availed Josh.”

If the two meanings can be taken at once, as two sides of the same coin, “availing yourself” means you are taking advantage of the moment as an opportunity to open yourself up and help others. Availing — whether you are availing yourself of the water of a found coconut or availing yourself to your community beach clean up day — is the dance of taking and giving.

To travel well you must avail yourself.

Walking into the session, ‘Exile & Belonging’, by Toko-pa, this was brought to my attention by my own neurotic self. I was feeling introverted and shy — there were 100 people in the room and I knew no one. You would think I would be used to this sort of thing as a traveler, but I’m not. In order to not have to face people and meet them, I had my back turned and was pretending to be absorbed in my notes. I felt out of place.

“Belonging is not a place. It is a competency.” — Toko-Pa

Toko-Pa shared many insights during her talk, but it is this quote that is circled twice in my notebook. By behaving in a shy manner, I was not availing myself and I was having the distinct feeling of not belonging because of it. Belonging is not a place, it’s a perspective and a willingness to avail yourself.

In our lives we will be in many places, in many rooms, and mostly with strangers. A feeling of belonging is a practiced art of flow and availability — available to others, to creativity, and to yourself. When you are available and availing, synchronicity shows up to the party and brings friends.

***

Jung was the first to say that synchronicity is as much a mystery as it is anything. And that is why I love it so much — you can see in glimpses the faint glimmer of some enormous interconnection, like the infinitely jeweled net of Indra cast over the cosmos, but yet it remains beyond comprehension.

October 27, 2014

The 12 best cities in North America to explore on a layover

Layovers. They’re bound to happen. So you might as well make the most of them. That’s easier said than done, though, depending on which airport you’re at.

Layovers can last just a few stressful minutes or drag on for hours, but one thing’s for certain: some layovers suck a lot less than others. In fact, if you find yourself in one of these North American cities, you may just discover that layovers can, well, kick ass. You know, these are the types of layover where you get out of the airport and explore the city in which you’re stranded, er, visiting for a very short period of time.

So get out your walking shoes, head to the nearest public transit point, and explore these 12 North American cities where you will actually enjoy a layover.

1

Vancouver, BC

Via: The Canada Line

Estimated time to downtown: 25-30 min

If New York City and Seattle were to have a love child, it would be Vancouver. Head straight to the beautiful, tree-lined boardwalk to watch seaplanes take off and land—during busy times they'll come in and take off every half hour or so. Along the boardwalk are several dining options with a selection of fresh seafood. A quick walk to the other side of the water will take you to Stanley Park, which hosts concerts and a plethora of activities. Stop by Prospect Pointe Cafe in the park for lunch and to absorb the gorgeous scenery. Don't wander off too far or you'll get lost in the vastness of the park and miss your next flight.

Photo: Magnus Larsson

2

Chicago, Illinois (via ORD or MDW)

Via: CTA Blue Line (ORD); CTA Orange Line (MDW)

Estimated time to downtown: 40-45 min (ORD); 20-25 min (MDW)

Regardless of whether you arrive in the Windy City via O'Hare or Midway, the CTA will get you to any downtown spot you want to go. Get off on either Washington (blue) or Randolph/Wabash (orange) and head to Giordano's for some authentic Chicago deep-dish pizza. It'll take 30-40 minutes for the pizza to arrive, so sit back and enjoy a beer or two. Go with a Goose Island brew for the (disputable) local flavor. A daytrip to Chicago wouldn't be complete without taking a selfie next to "The Bean" (technically named Cloud Gate). Located in Millennium Park, the area has much to offer, including the famous Art Institute of Chicago.

Photo: Sergey Gabdurakhmanov

3

San Francisco, California

Via: BART (many stops in downtown; Embarcadero most popular)

Estimated time to downtown: 25-30 min

Take BART from the airport to last the San Francisco stop, The Embarcadero. Depending on the day and time of your visit, you'll be able to enjoy an open air market and possibly a large farmers' market just outside the pier terminal building. From the backside of the ferry building you'll get a nice view of the Bay Bridge and AT&T Park, home of the San Francisco Giants.

From there, take a walk along the Embarcadero for a collection of views and activities that'll lead you to Fisherman's Wharf, the classic tourist trap with plenty of redeeming qualities such as sea lions off Pier 39. Learn the processes of bread making and chocolate making at San Francisco's famous Boudin and Ghirardelli, respectively. Take a ride on a cable car for an old-school San Francisco experience. Get off at Lombard Street to see one of America's steepest and most-crooked streets, with beautiful flower gardens and mansions at the switchbacks. Hop back on the cable car and get close to the North Beach neighborhood for a less-frequented adventure. North Beach is famous for being the setting for much of the writing done by the "beatniks" of the 1950s. On the corner of Broadway and Columbus, you'll find The Beat Museum, dedicated to the Beat Generation and, specifically, to the Beat writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Bukowski, William S. Burroughs, and Neal Cassady. Another option, just as worthy, is to spend the time at Golden Gate Bridge and Golden Gate Park. You'll have to take another bus from the BART to get there, but the bridge, one of the Wonders of the Modern World, is iconic San Francisco and would be a shame to miss.

Photo: Christopher Chan

4

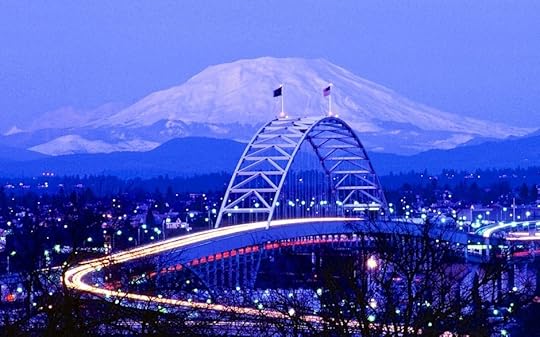

Portland, Oregon

Via: TriMet MAX Red Line

Estimated time to downtown: 30-35 min

Everything in Portland, Oregon seems to have a cult following: Voodoo Doughnut, Powell's Books, Chuck Palahniuk, food trucks, and Portlandia. Start the day off right with a hearty bacon-topped maple bar at Voodoo Doughnut, or perhaps you're more of a cereal person and would prefer one of their cereal-topped doughnuts, such as the Captain my Captain. They even have doughnuts for vegans! Next, head up to mammoth bookstore, Powell's City of Books. The store occupies an entire block and four stories. Retrieve a map upon entering or you may get lost. Local author Chuck Palahniuk, famously known for the award-winning novel Fight Club, is featured in the store. Once you have worked up an appetite from navigating the IKEA of bookstores, hit up the food trucks that collectively gather in groups called pods. Over 500 food trucks may occupy the city at any given time. The largest concentration of food carts in America can be found at SW 9th and Alder with 60 or more food carts. The city is also home to 56 breweries, according to the Oregon Brewers Guild, the most of any US city. Finally, be sure to stroll through Forest Park, Washington Park (most popular amongst tourists, with spectacular views of the city), or Waterfront Park.

Photo:

Photo: Andrew Hitchcock

12

Salt Lake City, Utah

Via: Trax (Gallivan Plaza may be the best stop)

Estimated time to downtown: 25 min

If you plan ahead, you could land in Salt Lake City on an early winter morning, rent a car for the day, go spend half the day skiing, and head back to the airport for a late evening flight. In the summer you could hike or bike in the mountains. To check out downtown instead, take Trax green line and get off at Temple Square. (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, better known as "The Mormons," offers free tours from the airport for those who have a layover of two hours or more.) Temple Square consists of 10 beautifully landscaped acres dedicated to buildings associated with the worship and organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The square is worth a visit regardless of your religious affiliation. Salt Lake City isn't all religion and skiing (which is a religion in its own right). Check out Squatter's Brewpub for a selection of locally crafted beer by two breweries, Squatters and Wasatch, that work together as the Utah Brewers Cooperative (you can find the brewpub in the airport as well). The beer on tap will be maxed out at 4%, per state law, so order by the bottle if you’re looking for something stronger.

Photo: Pedro Szekely

7 signs you've never had real BBQ

Image by Josh Bousel

1. You’ve only visited places that say ‘World Famous’ on their sign / menu item.

If they need to say they’re ‘World Famous’, they don’t have the goods. Great BBQ attracts customers by word of mouth about their tasty meats, not aggrandizing claims.

Tip: Let several friends try the ‘World Famous’ BBQ before you spend your money. If it’s worth your time, they’ll tell you.

2. You don’t know what a smoke ring is.

If your favorite smoke ring happened with five high school buddies standing in a circle passing a joint…you may not know real Q. While it may have been a good time, it wasn’t a smoke ring — BBQ style. A real smoke ring is the ¼ inch or so pink discoloration just under the surface of smoked meats.

3. You’ve never been served ribs or smoked chicken on butcher-style paper.

Many great BBQ places still serve their meals on a piece of brown butcher paper. When done without pretense, this old school style does more than just add ambience, it shows the restaurant puts more into the cooking of their meats than anything else. And that is very important!

More like this: A photographic ode to grilled meat around the world

4. Your favorite restaurant sends meat to the table smothered in sauce.

Not everyone likes a lot of sauce. Some even think well cooked Q should be able to stand on its own — sans sauce. If your pulled pork sandwich or sliced brisket comes covered in sauce (instead of having sauces available if desired), they’re possibly masking unwanted flavors or, at worst, making up for a lack of real smoke flavor.

Tip: If you can’t get sauce on the side, go elsewhere. Remember, they’re probably covering more than the meat with that sauce, like poor flavor.

5. You think liquid smoke takes the place of using an actual smoker.

This is just ridiculous. Some, maybe even many, competition BBQ teams use liquid smoke (added into their sauce for example) as a supplement, not a replacement, to the smoke flavor cooked into their meat during the smoking process. Let’s say that again. It’s a supplement, not a replacement.

6. You eat a certain ‘style’ rib when you aren’t in that area.

As a rule, to get great BBQ, only eat the style that is specific to the area you’re eating in. Don’t order the Carolina pulled pork sandwich in Memphis. Eat the RIBS! You’re going to get an authentic product, not a fake representation.

Tip: Don’t order the KC style ribs in Zagreb, Croatia — they’re not good (I live in KC so I HAD to try them!).

7. You enjoy the gimmicks more than the BBQ.

If a restaurant uses a gimmick to lure you in, like cute cartoon pig signage or a kitschy atmosphere, then doesn’t deliver with great taste, they’ve got their priorities out of order. And if you love going to a BBQ joint for the gimmicks and not the tasty meat, you’re priorities are more than a bit skewed too.

Tip: Check online or with friends to find out what is considered the BEST BBQ in your city. Eat there. Once you do, you’ll forget about the gimmicky place you used to go.

10 signs you're culturally Brazilian

1. You can’t live without your daily dose of novelas. And you got over that nonsense about local soap operas being a valuable window for the country’s heart. They’re just fun as fuck.

2. You’ve developed a taste for ice cold beer. And you know exactly how many caipirinhas you can handle before passing out.

3. Every meal just gets better if a side dish of farofa is at the table.

4. Busts are nice, sure. But you’ve become a butt-oriented person (it goes for men and women alike).

5. You have no problem walking the streets in flip flops. Also, gym clothes and beachwear are now part of your style.

6. “I’m on my way” means you’ll spend some time on Facebook, have a shower, talk on the phone for a while…and then leave. Maybe.

7. 17º C? Time to get that winter coat out of the closet!

More like this: You know you've been in Rio a while when...

8. You were sad when Orkut went offline and you lost your collection of testimonials, communities, and crushes.

9. Most important time of the year? Carnival. But you know the joy of the month of June, when Festas Juninas take over the country with delicious food, lovely music, and dancing.

10. You can’t understand the fuss around Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda. After all, Brazilian kids grew up watching this on television.

12 things Aussies love to hate

1. Kiwis

No, we’re not talking about the fruit here. First and foremost, Australians love to hate those friendly folks from the country below them in geography (and value, in their opinion). New Zealanders flock to Australia to live, work, and complain about how much better their home country is. If it’s so much better, well, fine, go home already!

2. The cold

If you’ve ever seen someone walking around in board shorts, flip flops, and a down puffy jacket in 75 degree weather, they were probably from Down Under. This sun-stained species cannot stomach a cool breeze, let alone something that resembles an actual winter.

3. Tony Abbott (or any Prime Minister, really…)

Most countries tend to smack talk their leaders to some degree, but Aussies have really turned this trend into an art form. Their current Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, has truly taken the cake for fueling this past time. Just do a quick Google search and jokes like this one are sure to top the list:

Q. What’s the difference between a picture of Kim Jong Un and a picture of Tony Abbott holding a potato?

A. One is a dictator and the other is a dick’n’tater.

4. Warm beer

Yes, who doesn’t hate warm beer? But in a country where beer is probably consumed more than water and temperatures are always soaring, warm beer is especially dreadful. If the bottle is not frosted, don’t take it out of the esky. As soon as you take it out, drink it quickly. Simple. As. That.

5. Tourists saying “Throw another shrimp on the barbie”

If you’ve ever visited the land of drop bears and kangaroos, you’ve uttered these words to some completely unamused local. Why is it so annoying to them? 1) They call shrimp “prawns” and 2) they eat them cold.

6. The letter R

Whether they know it or not, Australians love to hate the letter R. While they can pronounce the ‘Rrrrrr’ sound properly when it comes at the start of words, they seem to struggle when it’s found elsewhere. Would you like a sip of wata? Or maybe a trip to Aye’s Rock?

7. Blowing out a plugger (a.k.a. flip flop)

It definitely sucks for any person when you take a step and feel the rubber strap of your sandal burst through its foam sole. However, when you only own that one pair of pluggers (remember the silent R), this can be absolutely detrimental. Thongs (yes, the sandal kind) are a staple in any Aussie’s footwear collection. A good pair of Havaianas and you’re set for all seasons…until it blows out, and you’re left barefoot in the middle of the outback.

8. Kangaroos

Tourists all seem to think that kangaroos are cute and adorable, but Aussies know that they are really rather pesky and annoying creatures. In the eyes of Australians, kangaroos are only good for two things: violently damaging the front of your car when they jump out from nowhere, and eating slightly smoked and smothered in delicious marinade.

9. Foster’s

“Foster’s: Australian for beer.” Or is it? Although Foster’s has proudly been supported by the legendary Paul Hogan (a.k.a. Crocodile Dundee), it was founded back in 1888 by two men from New York. Nowadays, it is very rare to find an Aussie who claims Foster’s as their beer of choice, let alone the brand representative of the whole bloody country.

10. Each other (especially when it comes time for the State of Origin match)

With only seven states, Australia has intense inner-continental rivalry. Aussies generally hate anyone living south of wherever they live. The Northern Territory bags on Queensland; Queensland wants nothing to do with New South Wales; New South Wales knows they are better than Victoria; Victoria can’t stand being so close to South Australia, and as mentioned above, everyone hates the Kiwis. And let’s not forget everyone also takes a crack at the Australian Capital Territory (where the good old Tony resides), Western Australia, and of course, Tasmania.

11. Cane toads

Cane toads were brought over from Hawaii to eat the sugarcane beetles destroying the sugarcane crops, but instead they left the beetles alone and ate all native pests instead. Now the Aussies are left trying to clean up this horrible mess of a species that keeps killing all the local wildlife. They are so adamant about demolishing the cane toads that you can find depositories all over the place to dispose of any you might catch and not want to smash on your own. Have a hankering for Frogger? Head down under for a little real life action edition…

12. Last drinks call

This list would not be complete without at least one other beer-related thing that Australians love to hate — last drinks call at the pub. When this horrifying sentence leaves the lips of the bartender, Aussies feel a mix between a rush of hatred towards the bartender and sheer panic. They head up to the bar and buy about five more beers…then get kicked out before they even finish the third.

Dad, thanks for making me a traveler

Image by Fikirbaz

DEAR DAD,

Since my earliest moments, you’ve told me about how when you were in high school you had a choice between getting a car and taking a trip to the Philippines for the Boy Scouts World Jamboree. You chose the Philippines.

Dad in the Philippines, just after high school.

You’ve never looked back.

I was five when we went to Spain. I remember chicken fingers, greasy and perfectly crisp, and sitting at a small restaurant table. I remember this was after a morning being pushed around in my umbrella stroller, staring up in awe at giant paintings by Picasso and Goya in the Prado Museum — paintings I knew nothing of then but would later learn about in school — but what I remember most clearly is eating those chicken fingers and knowing, somewhere inside my little five-year-old heart, we weren’t at home. We were somewhere else. I kept my first travel journal on that trip, because even then you were teaching me to remember.

I was 11 when you pulled us out of school in Chicago and took us to Sydney. It was my first, but not last, study-abroad experience. I remember standing on the balcony while you took photos of my first day of school “Down Under.” My uniform was plaid and I wore a maroon scrunchie in my hair. You snapped away as I listed to the sound of the waves crashing below our apartment. I thought about how I loved the ocean, and how I felt at home even though we were halfway around the world. And then, like any kid anywhere, I went to school.

It was the other side of the world and yet it felt all the same to me somehow. My new school friends tried to talk me into tasting Vegemite, but I was skeptical of the salty paste that smelled like leather. You told me I might be surprised, and that part of life is being willing to try new things. I hated the Vegemite. But I liked the idea of being brave enough to seek out strange and unknown experiences. I still do.

By junior high, back in Illinois, my friends would joke about how you worked for the CIA; you were always off somewhere we hadn’t heard of, and I could rarely account for your whereabouts. The world felt so big then, and you felt very far away. But I was proud of you, and enjoyed bragging to anyone who would listen about how my dad was in South Africa, my dad was in Buenos Aires. You have made the world seem small for me, in the best way. You have taught me to hustle and to network and to figure out a way to make things happen. And I learned that you can always find a way to see the world, even if you’re not in the CIA.

Then I was in high school, and it was my first time traveling without you. It was the Dominican Republic. I watched my wide-eyed schoolmates observing the holes in the floor of our bus, and later, the leaky A/C units over our beds and men with huge guns guarding our hotel. I wasn’t wide-eyed, and I moved without their trepidation or discontentment. Instead, I went and stood on our hotel’s rooftop deck and looked out over Santo Domingo. While this place was new and different and you weren’t there with me, I was content because you had shown me that travel — and life — rarely goes as planned. I’d come to see that as part of the adventure. While my schoolmates whispered to one another about going home, I wondered if the Dominican Republic felt to me like the Philippines felt to you. I wanted to thank you then, standing on that roof.

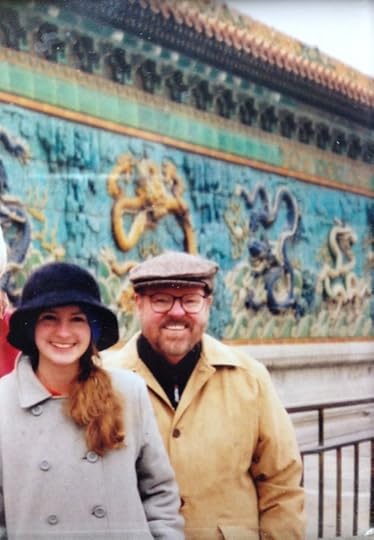

On a trip to China during my formative teenage years.

While my childhood friends went on vacations to Wisconsin Dells and Disney World, I found myself walking the Great Wall of China, taking helicopter rides in New Zealand, and swooning over lavender fields in Provence.Sometimes I was jealous of my friends’ water slide and theme park memories. Swapping stories at school, they would look at me with heads tilted in confusion, a resounding chorus of “Where’s that?” Some days, I wanted to be the same. But I trusted you, and I knew you had reasons for dragging me to these corners of the Earth. And I couldn’t be who I’ve become today without those little glimpses of distant lands — each place visited, each place where I held your hand and my feet sank into the earth has been woven into the very fabric of who I am.

After college, you and I went to Istanbul. The trip seemed like all our others, with that blue Rick Steves guidebook tucked under your arm and those cargo pants you always wear on, but it was entirely different for the small but unmistakable difference that you didn’t take me; we went, together. Me, the traveler, learning to do it on my own. We watched the sunset behind a minaret skyline from a boat on the Bosphorus, and everything was the same, and everything was different. You invited me to dinner with your university colleagues and I admired you once again, as I have for most of my life — this time for the fact that everywhere you went in the world, you had a friend. I couldn’t wait to make that story my own.

I used to roll my eyes at how you would always stop and take pictures. I would grow impatient — I couldn’t imagine why you would need so many memories. But those giant albums of photographs you keep in the attic hold some of the best moments in my life. When I’m home I pull them out, run my hand over our faces, across narrow European streets, across me in the maroon scrunchie with that distant look in my eyes, across the minarets of Istanbul. The whole world, and my whole life, is sprawled across each page. These days I’m the one stopping the car at scenic viewpoints, coming home with maxed-out memory cards or handfuls of film in my pockets. Like father, like daughter. I get it now.

I remember looking at all the stamps in your passport and wondering if mine would ever look like yours when I grew up. I remember the little bags of currencies from all over the world, leftovers from your trips that you kept in your desk drawer for “next time.” You always taught me to travel like there was going to be a next time. You’ve collected a lifetime of stamps and loose change and stories. While you were doing it, you made the entire world my home.

And now, here I am at 27, with no car, no lease, and no plans. I have a feeling I’ll choose the Philippines.

What journalists carry: Adam Bailes

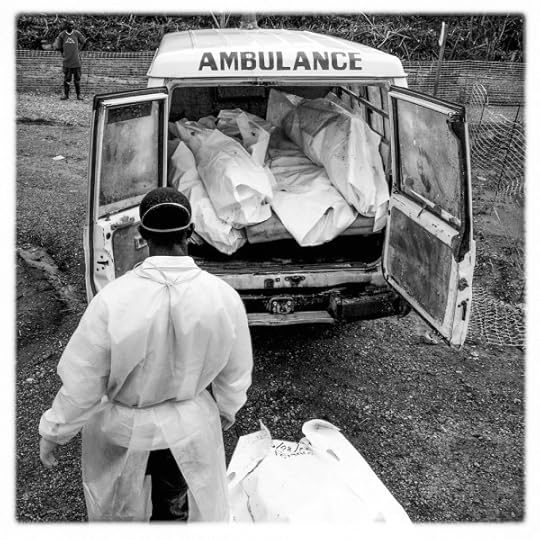

Red Cross (IRC) burial teams work tirelessly collecting moving and burying body’s. Many who have died of ebola. The work is dangerous and pay is low. Kailahun, Sierra Leone. All photos: Author.

Matador is teaming up with the FFR1 to show you what conflict and foreign freelancers carry with them on assignments.

Adam Bailes wearing personal protective clothing while filming in Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak.

“I am a video journalist currently based in West Africa. I grew up in Sheffield in the UK but I don’t think I have stayed in the same place longer than six months since I left school.

Over the past four years I have worked as a filmmaker and photographer in countries such as Ukraine, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Lebanon, South Africa, and Europe. I regularly produce work for TV and online news. Most recently I’ve been covering the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone West Africa.”

View more of Adam’s work on his site and follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

My everyday DSLR bag for shooting video and stills

1. G3 wireless mics — especially if it’s a busy or noisy place

2. Think tank card case — not waterproof but it holds lots of cards and is small enough to fit in my pocket

3. Zoom H4 — for my lapel mic so I can monitor and record sound separately

4. 5D MK ii + 35mm F2 IS. + small black strap of an old Nikon — IS or image stabilization is perfect for hand-held video

5. 24-105 F4 IS — my number one lens

6. Zacuto z finder + eye cushion — for bright sunlight and the cushion stops sweat when its hot

7. Rode shotgun video mic and windshield

8. Moleskin notepad — I have a stack of them but this little one lives in my camera bag

9. Alcohol-based hand sanitizer — I use about a bottle a day at the moment and I rub it on my hands, arms as well as my gear

10. Loads of spare batteries — sometimes it can be a few days between charges

11. Pens + sharpie — so I can write on anything anytime

12. Rocket lens blower for sand and dust

13. iPhone car charger + In ear headphones — quality is great and easy to replace

14. Dry bag and Domke shoulder bag — stops cameras from getting wet when there’s a downpour

15. Face mask (not pictured) — I use it when close to bodies, but only because there so much chlorine spray in the air

When I shoot for news

1. Three meter XLR cable — small enough so it doesn’t get in the way, but quick and perfect length if I want to take it off my camera to get closer to subjects

2. Canon Xf100 tiny broadcast-quality camera

3. Rode NTG1 shotgun mic + windshield — durable and excellent quality

4. Soft bag for batteries or spare cables

5. iPhone battery case — gives me an extra day between charges and also offers great protection

6. A really good set of headphones — two channels for if I’m running multiple sound

7. Everywhere, green and orange tape — I use it to mark, label and repair my kit

8. Batteries — enough but not too many

9. Think tank card reader + lots of CF cards 4x32GB, 2x16GB

10. Always keep a coin for swapping base plates

What I carry in my pockets

Scarf for the motorbike — keeps the dust out of my mouth and a whole bunch of other things

Tatty old wallet — I put a small amount of day-to-day money in here, so I have nothing to worry about if it gets stolen

Wad of local currency — I keep this separate in a safe pocket

Malaria tablets + paracetamol

Sunglasses — the most useful thing even if it’s not sunny, they stop the wind and dust from getting in my eyes

Red Cross (IRC) burial teams workers stare at bodies in back of an ambulance. Only half are loaded. A lack of resources means that many bodies have to be transported at the same time. Kailahun, Sierra Leone.

1The Frontline Freelance Register (FFR) is a representative body for freelancers, created and run by freelancers. It is an independent, ring-fenced entity which sits within the Frontline Club Charitable Trust with membership open to all freelance journalists working in conflict or foreign reporting. The FFR’s core objective is to support the physical and mental well-being of freelance journalists. In a world where staff jobs and fully paid foreign assignments are increasingly scarce, foreign and war reporting is dominated by freelancers, many of whom are deeply committed professionals doing outstanding work. At the same time, many of these freelancers lack the institutional support and the financial means to adequately manage the challenges of operating in dangerous environments in the long term. They also lack organised representation, often leaving them at the mercy of powerful media groups. FFR aims to help freelancers by providing them with a forum, a representative body, and a critical mass to face some of these challenges.

October 26, 2014

12 of the best Airbnbs in Copenhagen

Denmark’s most populated city and its capital, Copenhagen has a large number of tourist attractions, from the Tivoli Gardens to the Little Mermaid Statue. In recent years, Copenhagen’s gained a reputation as a gastronomic powerhouse, bringing tourists from all over the world that may never have imagined they’d end up in Denmark. Along with unique foods, Copenhagen offers unique accommodations in the form of Airbnbs all over the city.

Take a look at 12 of our favorites in Copenhagen, from houseboats to penthouses.

One

If you’re traveling with a large group, this two-story Frederiksberg penthouse may be your apartment of choice as it accommodates nine guests. You won’t get tired of your travel companions with five bedrooms, a living room, an open kitchen, and a terrace to escape to. The private terrace provides a 270-degree view overlooking picturesque gardens and Copenhagen rooftops. A visit to nearby Tivoli, the most visited theme park in Scandinavia, is in the realm of possibility too.

(View the listing)

Two

Bright and cozy, this Copenhagen apartment’s ideal for a group of friends. For the gastronomes out there, the apartment’s walking distance to a number of Michelin-star restaurants (does the name Noma ring a bell?). Housing two living rooms and a hot tub, this rental will make you feel at home — or you’ll hope this is your new home, anyway. With a view of the Copenhagen Opera House, the location of the apartment’s hard to beat. It’s just around the corner from the Nyhavn (literally, “new harbor”) neighborhood.

(View the listing)

Three

Located in central Vesterbro, this spacious apartment’s ideal for sightseeing. With plenty of cafes, bakeries, and grocery stores close by, you won’t go hungry. One has to mention the tasteful Scandinavian decor — you won’t forget where you are once you return after a packed day. You’ll get your daily workout climbing the stairs leading up to the fifth-floor apartment as the building is elevator-less. The stunning view of the park makes the walk upstairs worthwhile.

(View the listing)

Four

This sunny, stylish gem of an apartment, located in trendy Nørrebro, won’t disappoint. The apartment, walking distance to everything from dive bars to designer shops, isn’t in too bad a spot for exploring the city. Be sure to take advantage of the bikes (included in the rental price) and grill in the shared backyard if you’re visiting during the summer months.

(View the listing)

Five

Another Nyhavn apartment, this one’s tucked away in a private courtyard behind the waterfront. You could say it’s a haven within the neighborhood’s hustle and bustle (sorry). The building, built in the year 1700, was recently refurbished, as evidenced by the modern yet classic look and feel of the apartment. Be sure to grab coffee and a pastry from one of the fantastic bakeries nearby to enjoy on the light-filled balcony during your stay here.

(View the listing)

Six

This restored Dutch houseboat named Gea, 15 minutes from downtown Copenhagen, appears to be straight out of a fairytale (no word on which one). If you go for a swim, there’s somewhere to hang dry your clothing too. But regardless of your activity of choice, this spot comes with a sea view that’s likely difficult to rival. Visiting Copenhagen during the winter? Don’t worry — the cozy interior and fireplace on board is sure to keep you warm.

(View the listing)

Seven

Despite the tiny bathroom (typical for Copenhagen), this apartment’s quite charming. Ideal for a couple, the apartment’s a “mix between old and new Danish design.” The flat’s only a couple hundred meters away from Islands Brygge, the lively waterfront area housing one of the four Copenhagen harbor baths. Need a plan after you leave the apartment? Rent a pair of bikes and explore the nearby neighborhoods.

(View the listing)

Eight

The second houseboat on this list, this one gives off a funky and eclectic vibe. Rebuilt using recycled materials, the interior’s likely to inspire you. The light-flooded living room overlooks the water and other houseboats, a unique experience you’ll treasure. Located in the old industrial area, once Denmark’s most populated workplace, the apartment will transport you to a different time and place. The boat’s artsy feel isn’t confined to the interior as the neighborhood’s filled with art studios, workshops, a large flea market, and music festivals.

(View the listing)

Nine

Just two kilometers from the city center, this apartment made the list due to its amazing views. The 160-square-meter first-floor apartment’s located on the edge of the inner lakes of Copenhagen. Even better than the upscale, bright interior is the lakeside view. If you’re looking to stay in Copenhagen for an extended period of time, you’re in luck — the host prefers long-time renters from January to April. You may never want to go home.

(View the listing)

Ten

Houseboat number three is bright and roomy, perfect for those looking for a unique experience right in the middle of Copenhagen. If you’re traveling with kids, you’ll love the neighborhood’s outdoor area, which has a campfire area, large trampoline, and slide for those moments you need downtime but the kids don’t. Just a 15-minute walk from City Hall Square, this boat’s centrally located but provides the rare experience of houseboat living.

(View the listing)

Eleven

The sun-filled two-level apartment has an open floor plan, impressive floor-to-ceiling windows throughout, and a seven-meter-long balcony with amazing views. You’ll have an espresso machine, iMac, Apple TV, and plasma TV with Blu-ray (to name a few of the apartment’s amenities) within your reach at all times. That is, when you’re not busy roaming Copenhagen’s streets.

(View the listing)

Twelve

Rounding out this list is another unique houseboat. This three-level houseboat may even convince those prone to seasickness to spend a night or two on board. Take it easy on the impressive deck after a hectic day of sightseeing. Tired of seeing the sights by foot? Luckily, the hosts include a kayak and bikes for those non-walking occasions.

(View the listing)

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers