Ash Maurya's Blog, page 13

June 25, 2014

How to Make Running Lean a Habit

Keeping a locked knee (or a completely straight leg) is key for one-legged balancing yoga poses.

A locked knee provides a solid foundation that keeps your foot grounded as you progress through the rest of the pose.

“If you don’t have a locked knee, your pose hasn’t even started.”

- Bikram Yoga Dialog

I get all this. Yet I still constantly struggle with keeping my knees locked even after years of yoga practice.

My brain knows what to do, but my body does not always follow.

I can’t help but draw a parallel to running lean where “locking your knees” corresponds to “tackling what’s riskiest in your business model”.

“If you aren’t tackling what’s riskiest, your learning hasn’t even started.”

Like locked knees, tackling what’s riskiest is simple to understand but deceptively hard to put into regular practice.

Here are a couple of reasons why…

1. The Curse of Specialization

Before yoga, I studied martial arts for several years where I was taught to do the exact opposite i.e. never to keep a locked knee. Not only do locked knees restrict mobility, but a misplaced kick from an opponent can have a really painful (and potentially disastrous) outcome.

“Keeping knees slightly bent” isn’t just applicable to martial arts. Almost every other sport from skiing to weight lifting dispels the same advice to prevent injury.

Years of prior practice in these other sports ingrained a muscle memory or behavior that is still hard for me to unlearn. This is what I label as the “curse of specialization”.

While overcoming old habits are part of the challenge, the problem is further exacerbated through misplaced fear.

2. Misplaced Fear

In the case of yoga, it is fairly easy to rationalize the contradictory advice. Yoga is different from other sports, it is less mobile, and people aren’t taking whacks at you. But the image of shattered knees (even though I have never had a knee injury – knock on wood) is still enough to make me slightly bend my knees under just enough tension.

===

These same forces are also at play in entrepreneurship which as you know is riddled with extreme uncertainty. When faced with extreme uncertainty, we reach into the past for guidance. Over the years though, each of us has honed both a specific set of skills along with a set of misplaced fears which actually hold us back.

For instance, software developers spend years honing their craft which is primarily an “inside the building” activity. Getting them outside the building to go talk to customers is not only perceived as non-productive work (because there isn’t any making involved), but it may also have the disastrous consequence of upsetting the customer or worse losing the customer. Really?

Similarly sales and marketing folks should only do what they are good at and stay clear from code, or risk bringing down the entire production system.

While there is a place for specialization, over specialization and misplaced fears help create organizational policies and silos that over time stifle innovation and can even negatively impact overall throughput.

Local (or sub) optimization is the enemy of overall organizational throughput.

The antidote to breaking this curse is replacing old ingrained habits with new ones. But behavior change is hard. Luckily there is now a science to it.

B = MAT

BJ Fogg, Director of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University, has developed a simple framework to model human behavior.

Behavior = Motivation * Ability * Trigger

Lets work through this framework to see how it can help us unlearn old behaviors and replace them with newer ones:

Motivation

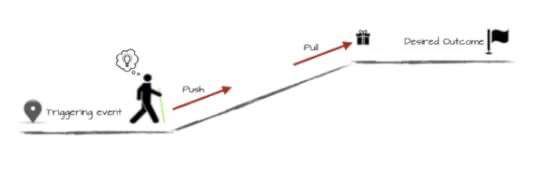

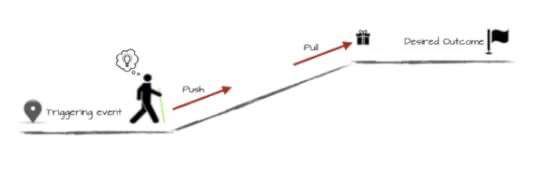

The first requisite ingredient for behavior change is some kind of an initial triggering event that motivates change i.e. it makes us desire a better outcome than the present.

Note: A number of you should recognize the picture above from my post on the “Physics of Customer Acquisition”. Yes, the same forces that drive customer behavior also apply to us at a meta level.

With yoga, my initial motiviation wasn’t the pursuit of spirituality or the many health benefits, but simply finding a more “efficient” exercise routine that I could fit into my busy schedule. Before Bikram, I used to frequent a gym, occasionally run, and meditate. Even at 90 mins a class, Bikram packed in a workout, meditation, and sauna in one. I gave it a shot and have been hooked ever since.

With running lean, I grew weary of having a 1-2 year cycle time going from an idea to a decision point where I would keep or kill off a product. As I wasn’t getting any younger and had more ideas than resources, this constraint motivated me to search for better and faster ways to vet new ideas.

“Life is Too Short to Build Something Nobody Wants”.

Ability

In order for a behavior to become habit forming, you need to have sufficient ability to complete the action. The action doesn’t necessarily have to be easy. It might even get you slightly outside your comfort zone but still be doable.

Many yoga instructors simply ask beginning students to hold the setup position for the entire length of the pose. You get on one leg and contract your quads until your knee cap lifts up. Then you hold this position for 30 seconds. Sounds simple, but after about 10 seconds you begin to feel your knee bending and have to constantly remind yourself to keep locking your knee.

Over time, muscle memory develops and you can then start progressing through the rest of the pose – still constantly reminding yourself to maintain your foundation which always fights to come undone.

In the examples above, you similarly need to adjust the activities for ability. Having a developer deliver a sales pitch or a salesperson deliver a complete feature could be aiming too high. Instead have the developer simply observe the customer interaction or the sales person commit low risk changes (like fixing spelling errors) at first to build muscle memory. Then gradually level up from there using additional triggers.

Trigger

While the initial trigger (or motivation) is the catalyst that starts the ball rolling, for the change to really manifest into habit forming behavior, you need periodic and regular triggers that keep bringing you back to the specific activity.

One of my favorite techniques here is employing time boxing + external accountability. It is very easy for us to cop out when no one is watching.

“If you fail in the forest, is it really a failure?”

While I can technically practice yoga at home, I practice 3 times a week at a studio for external accountability. Constantly getting called out for not locking my knees by more than one instructor creates a repeatable trigger that reinforces the importance of this action.

With running lean, I employed external accountability right here on this blog with my first blog post. The expectation to continually share my learning around lean is what drove me to continue writing (and eventually teaching) on a regular basis.

I often recommend that entrepreneurs first set up their own external accountability systems and reporting cadence before committing to any project for exactly this reason.

These periodic triggers provide an opportunity for deliberate practice which is key for mastering anything new. Just make sure you gradually level up on ability, use motivation for your desired outcome to push you, and you’ll be locking your knees in no time.

Neo: What are you trying to tell me? That I can dodge bullets?

Morpheus: No, Neo. I’m trying to tell you that when you’re ready, you won’t have to.

Lock Your Knees

Keeping a locked knee (or a completely straight leg) is key for one-legged balancing yoga poses.

A locked knee provides a solid foundation that keeps your foot grounded as you progress through the rest of the pose.

“If you don’t have a locked knee, your pose hasn’t even started.”

- Bikram Yoga Dialog

I get all this. Yet I still constantly struggle with keeping my knees locked even after years of yoga practice.

My brain knows what to do, but my body does not always follow.

I can’t help but draw a parallel to running lean where “locking your knees” corresponds to “tackling what’s riskiest in your business model”.

“If you aren’t tackling what’s riskiest, your learning hasn’t even started.”

Like locked knees, tackling what’s riskiest is simple to understand but deceptively hard to put into regular practice.

Here are a couple of reasons why…

1. The Curse of SpecializationBefore yoga, I studied martial arts for several years where I was taught to do the exact opposite i.e. never to keep a locked knee. Not only do locked knees restrict mobility, but a misplaced kick from an opponent can have a really painful (and potentially disastrous) outcome.

“Keeping knees slightly bent” isn’t just applicable to martial arts. Almost every other sport from skiing to weight lifting dispels the same advice to prevent injury.

Years of prior practice in these other sports ingrained a muscle memory or behavior that is still hard for me to unlearn. This is what I label as the “curse of specialization”.

While overcoming old habits are part of the challenge, the problem is further exacerbated through misplaced fear.

2. Misplaced FearIn the case of yoga, it is fairly easy to rationalize the contradictory advice. Yoga is different from other sports, it is less mobile, and people aren’t taking whacks at you. But the image of shattered knees (even though I have never had a knee injury – knock on wood) is still enough to make me slightly bend my knees under just enough tension.

===

These same forces are also at play in entrepreneurship which as you know is riddled with extreme uncertainty. When faced with extreme uncertainty, we reach into the past for guidance. Over the years though, each of us has honed both a specific set of skills along with a set of misplaced fears which actually hold us back.

For instance, software developers spend years honing their craft which is primarily an “inside the building” activity. Getting them outside the building to go talk to customers is not only perceived as non-productive work (because there isn’t any making involved), but it may also have the disastrous consequence of upsetting the customer or worse losing the customer. Really?

Similarly sales and marketing folks should only do what they are good at and stay clear from code, or risk bringing down the entire production system.

While there is a place for specialization, over specialization and misplaced fears help create organizational policies and silos that over time stifle innovation and can even negatively impact overall throughput.

Local (or sub) optimization is the enemy of overall organizational throughput.

The antidote to breaking this curse is replacing old ingrained habits with new ones. But behavior change is hard. Luckily there is now a science to it.

B = MATBJ Fogg, Director of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University, has developed a simple framework to model human behavior.

Behavior = Motivation * Ability * Trigger

Lets work through this framework to see how it can help us unlearn old behaviors and replace them with newer ones:

MotivationThe first requisite ingredient for behavior change is some kind of an initial triggering event that motivates change i.e. it makes us desire a better outcome than the present.

Note: A number of you should recognize the picture above from my post on the “Physics of Customer Acquisition”. Yes, the same forces that drive customer behavior also apply to us at a meta level.

With yoga, my initial motiviation wasn’t the pursuit of spirituality or the many health benefits, but simply finding a more “efficient” exercise routine that I could fit into my busy schedule. Before Bikram, I used to frequent a gym, occasionally run, and meditate. Even at 90 mins a class, Bikram packed in a workout, meditation, and sauna in one. I gave it a shot and have been hooked ever since.

With running lean, I grew weary of having a 1-2 year cycle time going from an idea to a decision point where I would keep or kill off a product. As I wasn’t getting any younger and had more ideas than resources, this constraint motivated me to search for better and faster ways to vet new ideas.

Ability“Life is Too Short to Build Something Nobody Wants”.

In order for a behavior to become habit forming, you need to have sufficient ability to complete the action. The action doesn’t necessarily have to be easy. It might even get you slightly outside your comfort zone but still be doable.

Many yoga instructors simply ask beginning students to hold the setup position for the entire length of the pose. You get on one leg and contract your quads until your knee cap lifts up. Then you hold this position for 30 seconds. Sounds simple, but after about 10 seconds you begin to feel your knee bending and have to constantly remind yourself to keep locking your knee.

Over time, muscle memory develops and you can then start progressing through the rest of the pose – still constantly reminding yourself to maintain your foundation which always fights to come undone.

In the examples above, you similarly need to adjust the activities for ability. Having a developer deliver a sales pitch or a salesperson deliver a complete feature could be aiming too high. Instead have the developer simply observe the customer interaction or the sales person commit low risk changes (like fixing spelling errors) at first to build muscle memory. Then gradually level up from there using additional triggers.

TriggerWhile the initial trigger (or motivation) is the catalyst that starts the ball rolling, for the change to really manifest into habit forming behavior, you need periodic and regular triggers that keep bringing you back to the specific activity.

One of my favorite techniques here is employing time boxing + external accountability. It is very easy for us to cop out when no one is watching.

“If you fail in the forest, is it really a failure?”

While I can technically practice yoga at home, I practice 3 times a week at a studio for external accountability. Constantly getting called out for not locking my knees by more than one instructor creates a repeatable trigger that reinforces the importance of this action.

With running lean, I employed external accountability right here on this blog with my first blog post. The expectation to continually share my learning around lean is what drove me to continue writing (and eventually teaching) on a regular basis.

I often recommend that entrepreneurs first set up their own external accountability systems and reporting cadence before committing to any project for exactly this reason.

These periodic triggers provide an opportunity for deliberate practice which is key for mastering anything new. Just make sure you gradually level up on ability, use motivation for your desired outcome to push you, and you’ll be locking your knees in no time.

Neo: What are you trying to tell me? That I can dodge bullets?

Morpheus: No, Neo. I’m trying to tell you that when you’re ready, you won’t have to.

May 8, 2014

How to Identify Your Riskiest Business Model Assumptions

The true job of an entrepreneur is to systematically de-risk their business model over time.

While you might be really excited by your idea’s potential, others don’t see what you see. What they see instead is something untested and risky.

You have to derisk your idea to convince your future co-founders to quit their stable jobs and join your cause.

You have to derisk your idea to convince customers to take a chance on your product versus the existing alternatives.

And you have to derisk your idea to convince investors to give you money to grow your business.

It logically follows that that you should prioritize tackling what’s riskiest, not what’s easiest, in your business model.

This was the basis for the 2nd meta-principle described in my book: Running Lean.

While tackling what’s riskiest is a simple enough concept to grasp, it’s ironically quite hard to put into practice.

When you fail to correctly prioritize your risks, it doesn’t matter how many experiments you run. You’ll get sub-optimal results and fail to pierce a certain ceiling of achievement.

This is why I came to realize that “identifying what’s riskiest” is the main Achilles Heel in Running Lean. I’ve spent the last year looking for a more practicable solution which is the main question I address in my next book: The Customer Factory.

But before I jump to the solution, lets first take a look at current approaches for risk prioritization and see where they fall short:

Approach 1: Use your intuition

You could just use your intuition and pick what that you consider as your riskiest assumption to test.

But testing anything takes time, money, and effort, and it’s not comforting to know that incorrect prioritization of risk is one of the top contributors of waste.

In other words, if you fail to correctly identify what’s riskiest, you end up burning needless resources and you’ll get those sub-optimal results and endless cycles I showed earlier.

Approach 2: Start with the 3 Universal Risks

At the earliest stages of a product, you can rely on tackling some universal risks that apply to almost every product such as making sure your customer/problem assumptions are valid, making sure these problems represent a monetizable pain (revenue stream), and making sure that you have a path or can build a path to customers (channels).

But as the product matures, no two products and entrepreneurs are the same.

What’s riskiest in one situation may not be what’s riskiest in the other – so it becomes impossible to follow a prescriptive path.

Approach 3: Talk to domain experts

A reasonably good solution is talking to domain experts and advisors. This can help uncover what’s riskiest – provided you have good advisors and you use them effectively by not just practicing “success theater” with them.

Seasoned advisors are good at pattern recognition and if you get a group of advisors independently raising the same objections in your model, that’s a pretty good indication that it may worth investigating.

But the opposite is also true.

In fact, it’s more common to get conflicting advice even from the best advisors. I’ve seen this happen at some of the best accelerators in the world.

At the end of the day, you and you alone have to own your business model. Keep in mind though that no one has a crystal ball and a tactic that might have worked for an advisor, such as using adwords to grow their business, may have outrun it’s time.

Advisor Paradox: Hire advisors for advice but don’t follow it, apply it.

-Venture Hacks

So you can’t take anyone’s advice on faith, you still have to test it. And the price of picking the wrong thing to test, costs you time, money, and effort.

So while each of these solutions gets you part of the way there, none of them is foolproof. The underlying reason for this is that all them require guessing – either you guess or you have someone with more experience than yourself guess.

There is better way that doesn’t require any guesswork: Using a systems based approach.

I first introduced systems thinking for your business model in this post and it’s the central idea in my next book: The Customer Factory.

There are 3 main attributes of systems and one of them is the concept of system constraints. Or specifically the idea that at any given point in time, a system is limited by a single constraint.

Those of you familiar with Goldratt’s book: The Goal will recognize this as the Theory of Constraints.

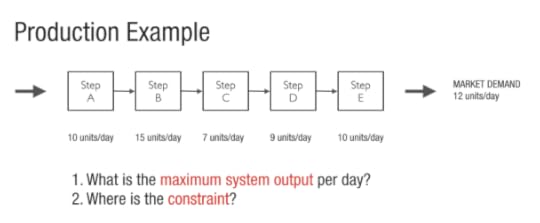

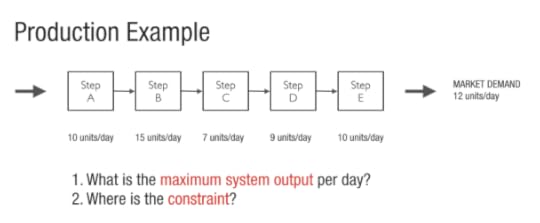

To illustrate this concept, consider this system of machines on a factory floor.

Each of these machines can generate a certain number of widgets per day. The market demands 12 units a day. But the system as it’s configured here cannot meet that demand.

If we wanted to increase the throughput of the system, we could upgrade all the machines but that would be very wasteful. What we need to do instead is find the constraint or bottleneck in the system which is limiting the throughput.

Can you figure out what is the maximum throughput of this system?

Where is the bottleneck or constraint in this system?

The maximum throughput of this system is limited by the constraint which is at step C because that machine is the slowest machine.

A lot of the units created in the first 2 steps just queue up at Step C waiting to be processed.

So if we manage to increase the throughput of Step C from 7 units a day to 12 units a day, what happens now to the throughput? And what happens to the constraint?

That’s right, the constraint moves. Throughput goes up but it’s still limited by the next slowest machine which is at Step D. So even though market demand is at 12 units, this system can still only produce 9 units a day.

This is one of reasons why correctly identifying what’s riskiest is so tricky especially when your business model is set in motion.

If you fail to identify the bottleneck in your business model, you get sub-optimal results. While you might still learn something from your experiments, you don’t get to increase the throughput of your business model unless that learning affects a limiting constraint.

If, on the other hand, you do correctly identify the right bottleneck and address it, you have to know when to stop or you fall into the premature optimization trap. This is because once the bottleneck is sufficiently addressed, a new bottleneck will appear and you have to move quickly to plug that hole.

Finding constraints in a “customer factory” is a bit more involved than the traditional factory example because there are a few more moving parts.

This is what I’ll be covering extensively in my next book: The Customer Factory which is slated for launch in 2015.

Until then, you can get a sneak preview of this content in this free 3-part video series:

On Identifying Riskiest Assumptions

The true job of an entrepreneur is to systematically de-risk their business model over time.

While you might be really excited by your idea’s potential, others don’t see what you see. What they see instead is something untested and risky.

You have to derisk your idea to convince your future co-founders to quit their stable jobs and join your cause. You have to derisk your idea to convince customers to take a chance on your product versus the existing alternatives. And you have to derisk your idea to convince investors to give you money to grow your business.It logically follows that that you should prioritize tackling what’s riskiest, not what’s easiest, in your business model.

This was the basis for the 2nd meta-principle described in my book: Running Lean.

While tackling what’s riskiest is a simple enough concept to grasp, it’s ironically quite hard to put into practice.

When you fail to correctly prioritize your risks, it doesn’t matter how many experiments you run. You’ll get sub-optimal results and fail to pierce a certain ceiling of achievement.

This is why I came to realize that “identifying what’s riskiest” is the main Achilles Heel in Running Lean. I’ve spent the last year looking for a more practicable solution which is the main question I address in my next book: The Customer Factory.

But before I jump to the solution, lets first take a look at current approaches for risk prioritization and see where they fall short:

Approach 1: Use your intuitionYou could just use your intuition and pick what that you consider as your riskiest assumption to test.

But testing anything takes time, money, and effort, and it’s not comforting to know that incorrect prioritization of risk is one of the top contributors of waste.

In other words, if you fail to correctly identify what’s riskiest, you end up burning needless resources and you’ll get those sub-optimal results and endless cycles I showed earlier.

Approach 2: Start with the 3 Universal RisksAt the earliest stages of a product, you can rely on tackling some universal risks that apply to almost every product such as making sure your customer/problem assumptions are valid, making sure these problems represent a monetizable pain (revenue stream), and making sure that you have a path or can build a path to customers (channels).

But as the product matures, no two products and entrepreneurs are the same.

What’s riskiest in one situation may not be what’s riskiest in the other – so it becomes impossible to follow a prescriptive path.

Approach 3: Talk to domain expertsA reasonably good solution is talking to domain experts and advisors. This can help uncover what’s riskiest – provided you have good advisors and you use them effectively by not just practicing “success theater” with them.

Seasoned advisors are good at pattern recognition and if you get a group of advisors independently raising the same objections in your model, that’s a pretty good indication that it may worth investigating.

But the opposite is also true.

In fact, it’s more common to get conflicting advice even from the best advisors. I’ve seen this happen at some of the best accelerators in the world.

At the end of the day, you and you alone have to own your business model. Keep in mind though that no one has a crystal ball and a tactic that might have worked for an advisor, such as using adwords to grow their business, may have outrun it’s time.

Advisor Paradox: Hire advisors for advice but don’t follow it, apply it.

-Venture Hacks

So you can’t take anyone’s advice on faith, you still have to test it. And the price of picking the wrong thing to test, costs you time, money, and effort.

So while each of these solutions gets you part of the way there, none of them is foolproof. The underlying reason for this is that all them require guessing – either you guess or you have someone with more experience than yourself guess.

There is better way that doesn’t require any guesswork: Using a systems based approach.

I first introduced systems thinking for your business model in this post and it’s the central idea in my next book: The Customer Factory.

There are 3 main attributes of systems and one of them is the concept of system constraints. Or specifically the idea that at any given point in time, a system is limited by a single constraint.

Those of you familiar with Goldratt’s book: The Goal will recognize this as the Theory of Constraints.

To illustrate this concept, consider this system of machines on a factory floor.

Each of these machines can generate a certain number of widgets per day. The market demands 12 units a day. But the system as it’s configured here cannot meet that demand.

If we wanted to increase the throughput of the system, we could upgrade all the machines but that would be very wasteful. What we need to do instead is find the constraint or bottleneck in the system which is limiting the throughput.

Can you figure out what is the maximum throughput of this system?

Where is the bottleneck or constraint in this system?

The maximum throughput of this system is limited by the constraint which is at step C because that machine is the slowest machine.

A lot of the units created in the first 2 steps just queue up at Step C waiting to be processed.

So if we manage to increase the throughput of Step C from 7 units a day to 12 units a day, what happens now to the throughput? And what happens to the constraint?

That’s right, the constraint moves. Throughput goes up but it’s still limited by the next slowest machine which is at Step D. So even though market demand is at 12 units, this system can still only produce 9 units a day.

This is one of reasons why correctly identifying what’s riskiest is so tricky especially when your business model is set in motion.

If you fail to identify the bottleneck in your business model, you get sub-optimal results. While you might still learn something from your experiments, you don’t get to increase the throughput of your business model unless that learning affects a limiting constraint.If, on the other hand, you do correctly identify the right bottleneck and address it, you have to know when to stop or you fall into the premature optimization trap. This is because once the bottleneck is sufficiently addressed, a new bottleneck will appear and you have to move quickly to plug that hole.Finding constraints in a “customer factory” is a bit more involved than the traditional factory example because there are a few more moving parts.

This is what I’ll be covering extensively in my next book: The Customer Factory which is slated for launch in 2015.

Until then, you can get a sneak preview of this content in this free 3-part video series:

February 18, 2014

The Science of How Customers Buy Anything

A basic tenet of running lean is validating a product or feature ideally without having to building it first. This makes complete sense when you look at every product or feature as it’s own customer factory.

The first battle isn’t fought on the ground but in the mind of the customer.

It isn’t fought with your built out solution but instead with an offer.

This is true not just at the earliest stages of defining your minimum viable product but at every stage of the product development cycle.

And here’s the key insight:

If you can’t get people inside your customer factory,

it doesn’t matter what’s inside.

The way you get them inside is with an offer.

What is an Offer

An offer is essentially a stand-in for your solution that validates sufficient customer pull for that solution.

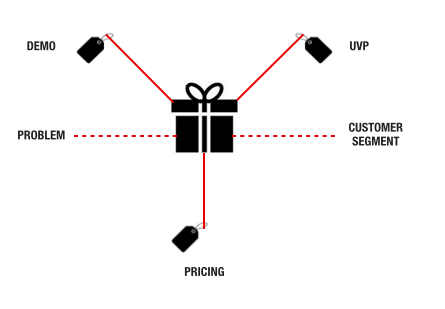

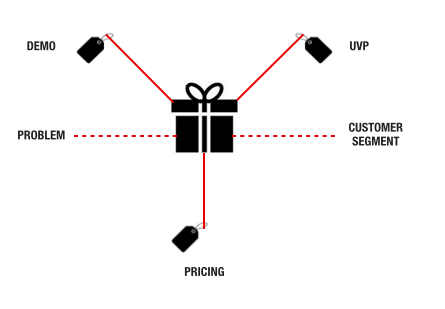

The offer is basically made up of 3 elements:

Your unique value proposition which gets the customer’s attention

Your demo which shows them how you get them from point A (current reality) to point B (desired reality)

Your price or derivative currency of exchange which locks in commitment

Assembling a Compelling Offer

Before you can create a compelling offer, you have to gain a deep understanding of your customers and their problems.

You have to understand your customers better than they even understand themselves.

In my book, Running Lean, I detailed several customer interviewing (Problem Interviews) and observation techniques for doing this.

Since the book though, I’ve taken the work further in my workshops and bootcamps to make it more practicable – incorporating the customer factory work, customer journey maps, and the jobs-to-be-done framework.

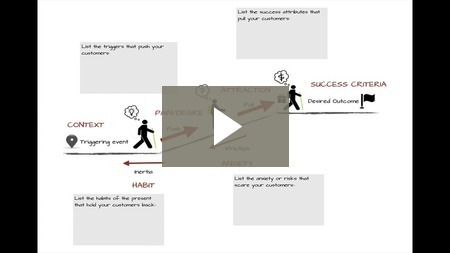

Here’s an example of one of the deliverables from the early problem/solution fit stage:

It’s a marked up customer journey map that details your customer’s current reality workflow. We can then extract several layers of insights and inject our solution into this diagram that feed directly into making a more compelling offer.

I’m not going to walkthrough the detailed analysis steps today but I will walkthrough the resulting diagram that captures the job of your offer.

The job of the offer is acquiring customers i.e. turning unaware visitors into interested prospects.

The 3 elements I shared above are what go into assembling an offer but you additionally need to understand how customers buy in order to deliver your offer.

The Motivational Forces That Drive Customers to Buy

This diagram is best built up as a story.

So here we go…

Scene 1: The Push of the Trigger

Here you have a customer who is merrily going along his way until he has some kind of a triggering event.

This triggering event pushes the customer to seek some desired better outcome or make some change towards progress.

The bottom of the hill is his current reality and the top is the desired future reality he wants to achieve.

This triggerring event could be something explicit like having a new baby or it could be something more subtle like maybe having 2 of your friends purchase a new car in the last month.

These subtle triggering events can sometimes be hard to find, but if you look, they are almost always there.

A new baby is a significant life-changing event that pushes people to seek out all sorts of new desired outcomes or products. The more subtle car example trigger might not actively push a person to purchase a new car but it may all of sudden make him more receptive to car advertisements or promotions.

For this reason, some triggers are more *immediately* actionable than others, but knowing the trigger(s) can help uncover both active and passive leads.

Scene 2: The Pull of Your Offer

Understanding the key trigger and desired outcome establishes the situational context you need to best deliver your offer and the success criteria you need to communicate in your offer.

If you get these right and place your offer in the right context, it pulls customers towards your solution versus other alternatives. This is where your carefully crafted UVP, demo, and pricing come into play.

If you have a big enough audience and/or brand, it is often possible to make your offer the triggering event.

Think of an Apple product launch.

A less extreme example is an educational webinar that upsells a product.

Scene 3: Overcoming Inertia and Friction

But only communicating the positive attributes of your product is not enough. You also have to address two negative forces that hold the customer back.

The first one is friction caused by the anxiety or uncertainty of embracing something new.

Here, the customer visualizes taking this journey towards your solution which triggers them into contingency planning mode. These are usually mental roadblocks that keep people from taking a chance on a new solution: “What if I pick the wrong solution?”

Some typical remedies to overcome this friction are building in risk reversals into your offer. 30 day trials, no credit card required, money-back guarantees, social proof, are all examples of these.

The other negative force is caused by inertia which keeps people from trying something new.

You can think of this as the switching cost of moving from the current solution to your solution. These may be caused by actual switching costs like annual contracts or more cognitive switching costs ingrained in current behavior or habits.

A key insight here is realizing that even when delivering a potentially new disruptive solution, you don’t get to recreate the customer’s workflow from scratch.

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPad, he didn’t tell us 10 new things we could do with the iPad, but rather showed us 10 old things we could do with the iPad – only much better.

So the right approach here isn’t redrawing the workflow or ignoring this inertia, but making the transition to your product as seamless as possible.

Note: You can see the solution injection (blue box) in the customer journey map above with an appreciation for the customer’s existing workflow.

I will also add that not all friction and inertia is bad. I often use some friction and inertia as a qualifying criteria for identifying my best early adopters.

Your early adopters should have above average push and pull to overcome some of these negative forces.

But make sure you focus on the right force:

Here is the completed diagram with some additional annotation.

This diagram is what I use in my work with entrepreneurs. After all the interviews, observations, and analysis, this is the macro level view that gets us talking about how best to craft and deliver a compelling offer.

Remember this is a journey that happens inside your customer’s mind which is why I show thought bubbles in the pictures above. The end result isn’t always a sale but commitment that gets your closer to turning that unaware visitor into a happy customer.

I’d like to acknowledge 2 sources of inspiration in the creation of this diagram:

The Forces Diagram by Bob Moesta and Chris Spiek from the Jobs-to-be-done framework

Marketing Experiments’ Conversion Sequence Formula:

C = 4m + 3v + 2(i-f) – 2a ©

Additional Resources

When you become a Practice Trumps Theory member (it’s free), you’ll get access to a more in-depth 10 minute video lecture on the “Physics of Customer Acquisition” from my Customer Factory Blueprint bootcamp program and a PDF worksheet for creating your own forces diagram.

The Physics of Customer Acquisition

A basic tenet of running lean is validating a product or feature ideally without having to building it first. This makes complete sense when you look at every product or feature as it’s own customer factory.

The first battle isn’t fought on the ground but in the mind of the customer.

It isn’t fought with your built out solution but instead with an offer.

This is true not just at the earliest stages of defining your minimum viable product but at every stage of the product development cycle.

And here’s the key insight:

If you can’t get people inside your customer factory,

it doesn’t matter what’s inside.

The way you get them inside is with an offer.

What is an OfferAn offer is essentially a stand-in for your solution that validates sufficient customer pull for that solution.

The offer is basically made up of 3 elements:

Before you can create a compelling offer, you have to gain a deep understanding of your customers and their problems.

You have to understand your customers better than they even understand themselves.

In my book, Running Lean, I detailed several customer interviewing (Problem Interviews) and observation techniques for doing this.

Since the book though, I’ve taken the work further in my workshops and bootcamps to make it more practicable – incorporating the customer factory work, customer journey maps, and the jobs-to-be-done framework.

Here’s an example of one of the deliverables from the early problem/solution fit stage:

It’s a marked up customer journey map that details your customer’s current reality workflow. We can then extract several layers of insights and inject our solution into this diagram that feed directly into making a more compelling offer.

I’m not going to walkthrough the detailed analysis steps today but I will walkthrough the resulting diagram that captures the job of your offer.

The job of the offer is acquiring customers i.e. turning unaware visitors into interested prospects.

The 3 elements I shared above are what go into assembling an offer but you additionally need to understand how customers buy in order to deliver your offer.

The Motivational Forces That Drive Customers to BuyThis diagram is best built up as a story.

So here we go…

Here you have a customer who is merrily going along his way until he has some kind of a triggering event.

This triggering event pushes the customer to seek some desired better outcome or make some change towards progress.

The bottom of the hill is his current reality and the top is the desired future reality he wants to achieve.

This triggerring event could be something explicit like having a new baby or it could be something more subtle like maybe having 2 of your friends purchase a new car in the last month.

These subtle triggering events can sometimes be hard to find, but if you look, they are almost always there.

A new baby is a significant life-changing event that pushes people to seek out all sorts of new desired outcomes or products. The more subtle car example trigger might not actively push a person to purchase a new car but it may all of sudden make him more receptive to car advertisements or promotions.

For this reason, some triggers are more *immediately* actionable than others, but knowing the trigger(s) can help uncover both active and passive leads.

Scene 2: The Pull of Your OfferUnderstanding the key trigger and desired outcome establishes the situational context you need to best deliver your offer and the success criteria you need to communicate in your offer.

If you get these right and place your offer in the right context, it pulls customers towards your solution versus other alternatives. This is where your carefully crafted UVP, demo, and pricing come into play.

If you have a big enough audience and/or brand, it is often possible to make your offer the triggering event.

Think of an Apple product launch.

A less extreme example is an educational webinar that upsells a product.

But only communicating the positive attributes of your product is not enough. You also have to address two negative forces that hold the customer back.

The first one is friction caused by the anxiety or uncertainty of embracing something new.

Here, the customer visualizes taking this journey towards your solution which triggers them into contingency planning mode. These are usually mental roadblocks that keep people from taking a chance on a new solution: “What if I pick the wrong solution?”

Some typical remedies to overcome this friction are building in risk reversals into your offer. 30 day trials, no credit card required, money-back guarantees, social proof, are all examples of these.

The other negative force is caused by inertia which keeps people from trying something new.

You can think of this as the switching cost of moving from the current solution to your solution. These may be caused by actual switching costs like annual contracts or more cognitive switching costs ingrained in current behavior or habits.

A key insight here is realizing that even when delivering a potentially new disruptive solution, you don’t get to recreate the customer’s workflow from scratch.

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPad, he didn’t tell us 10 new things we could do with the iPad, but rather showed us 10 old things we could do with the iPad – only much better.

So the right approach here isn’t redrawing the workflow or ignoring this inertia, but making the transition to your product as seamless as possible.

Note: You can see the solution injection (blue box) in the customer journey map above with an appreciation for the customer’s existing workflow.

I will also add that not all friction and inertia is bad. I often use some friction and inertia as a qualifying criteria for identifying my best early adopters.

Your early adopters should have above average push and pull to overcome some of these negative forces.

But make sure you focus on the right force:

Here is the completed diagram with some additional annotation.

This diagram is what I use in my work with entrepreneurs. After all the interviews, observations, and analysis, this is the macro level view that gets us talking about how best to craft and deliver a compelling offer.

Remember this is a journey that happens inside your customer’s mind which is why I show thought bubbles in the pictures above. The end result isn’t always a sale but commitment that gets your closer to turning that unaware visitor into a happy customer.

I’d like to acknowledge 2 sources of inspiration in the creation of this diagram:

The Forces Diagram by Bob Moesta and Chris Spiek from the Jobs-to-be-done framework Marketing Experiments’ Conversion Sequence Formula:C = 4m + 3v + 2(i-f) – 2a ©

October 3, 2013

How To Interview Your Users And Get Useful Feedback

(This is guest post by Garrett Moon, Founder of TodayMade.

It’s not enough just to talk to customers. You have to know how.

In this post, Garrett shares his lessons learned for crafting effective customer interviews.

Enjoy…

-Ash)

When my business partner and I drafted our first outline for our next startup venture, we knew that we were onto something pretty exciting. The existing market had little to offer in terms of a great editorial calendar for blogging, and we felt that our unique approach would resonate with users. Despite our excitement, we wanted to validate our idea. We started gathering feedback through user interviews.

One of the lessons I learned after killing my first product was that I needed to pay better attention to how I was gathering feedback. That experience showed me that I had a fundamental misunderstanding on how to actually go about getting good feedback.

With the new product, I vowed to double my efforts and do it right. I bought the book Interviewing Users by Steve Portigal and studied the art of interviewing. The investment in that book was one of the key ingredients to a successful launch. Even more importantly, it is something that anyone can duplicate.

Fast-forward to today, you’ll hear me say that there is nothing more energizing and useful than interviewing your users. As a born introvert, it took me some time to understand and accept this, but learning to get over my own inadequacies and give people a call made a huge difference in the amount and the quality of feedback that we received.

Not only were we able to make connections with potential customers, but we were also about to understand their true needs. Interviewing is an art, though, and you must approach it with reverence.

Interviewing Tip #1: Stop Sounding Like An InventorAs an entrepreneur, it is actually somewhat counter-intuitive to conduct a user interview. Deep inside almost every starter is a little bit of salesmen, but this is counterproductive when collecting user feedback. Conducting an interview doesn’t call for a sales pitch. We have to be in it for the information.

A classic example of this is when an interviewee asks for a specific feature that they would like you to include. The salesperson inside of us wants to pounce on that idea and let the user know that it is something we are considering. This is our instinct, but it is not the best way to gather feedback.

September 12, 2013

How to Get Customers to Want to Pay Even Before Building Your Product

The following is an excerpt from my book: Running Lean.

In my post Why You Should Never Ask Customers What They’ll Pay? I covered how to set initial pricing for your product by first spending time to understand your customer, their problems, and their existing alternatives.

In this post, I’ll talk about how you use that information to test pricing.

When to Test PricingThe general feeling around your first release (or minimum viable product) is that it’s embarrassingly minimal so it’s more common to want to discount or give it away in the interest of learning from customers. The mindset most of us have is one of “lowering sign-up friction”. We want to make it as easy as possible for the customer to say yes and agree to take a chance on our product – hoping that the value we deliver over time will earn us the privilege of their business.

Not only does this approach delay validation of one of the more riskier components of the business model because we make it too easy for customers to say yes, but a lack of strong customer “commitment” can also be detrimental to optimal learning. Your job is finding early adopters who are at least as passionate about the problems you’re addressing as you are.

There is no business in your business model without revenue.

Lowering sign-up friction is a valid tactic once you’ve got a customer lifecycle that is working. Until then, the goal is maximizing for learning, not scaling.

If you intend to charge for your product, you should start testing pricing even before you build your MVP.

Remember from the last post, that pricing is very much a part of your product.

I know this may run counter to your intuition. It did with mine. Here’s a social experiment I ran during one of my customer interviews (and have repeated several times since then) that changed my perspective.

I’ve left out the names of the product and customer:

I had just finished demoing the solution and validated that we had a real “must-have” problem and solution on our hands.Me: So lets talk about pricing…

Customer: Do we need to negotiate pricing right away?

Me: This is not really a negotiation. While we have been using this product internally ourselves, we need to justify whether it’s worth productizing externally.

Customer: Oh ok.

Me: So what would you pay for this product?

Customer: I don’t know – probably something in the $15-20/mo range.

Me: Well, that’s not the pricing we had in mind. We want to start with a $100/mo plan. I can understand why you don’t want to pay a lot (because you are pre-revenue) and it’s possible that we’ll offer a freemium or starter plan in the future.

Right now, we are specifically looking for 10 [define early adopters] who clearly have a need for [state top problem]. We will work closely with these 10 companies to validate [state unique value proposition] within 30-60 days or give them their money back.

You mentioned that you’ve spent several developer hours a month building a homegrown system and still haven’t been happy with the results. This product is our third attempt. Given your current homegrown system, can you build your own homegrown system, which is a non-core function, spending less than 2 developer hours a month ($100/mo is less than 2 developer hours a month)?

Customer: Yes, that makes a lot of sense. We want to be on the shortlist. When you put it that way, I can easily justify paying $1200/yr. It’s just a fraction of what we pay our developers. How do we get on the list?

Me: We’re still finalizing some product details and I’ll get back with you once we’re ready.

Customer: We seriously want to part of the initial customer list. I’ll run upstairs and get my checkbook if you want me to…

So what happened there? Why did the customer agree to paying 5x their original amount?

There were a number of principles in play that I’ll summarize:

Prizing: Oren Klaff discusses this framing technique in his book: Pitch Anything. He describes how in most pitches, the presenter plays the role of a jester entertaining in a royal courtyard (of customers). Rather than trying to impress, position yourself to be the prize.

Here’s how he applies this to pitching investors. Rather than ending the pitch with an ask for money, he reframes the conversation by showing them an impressive list of board members and asks them to justify whether they would be qualified to serve on the board.

Scarcity: The “10 customer” statement from my interview above was not a fake ploy. The first objective with your MVP is to learn. I’d much rather have 10 “all-in” early adopters I can give my full attention than 100 “on-the-fence” users any day.

Read my 10x Product Launch post for more on this.

Anchoring: Last time, I illustrated the relativity principle in action using Steve Jobs’ iPad keynote. Even though pricing against “existing alternatives” might seem logical, the customer might not automatically make the reference themselves. If Steve Jobs saw the point to explicitly anchor pricing, none of us have an excuse.

Confidence: Most people are reluctant to charge for their MVP because they feel it’s too “minimal” and might even be embarrassed by it. I don’t subscribe to this way of thinking. The reason I painstakingly test problems and reduce scope is to build the “simplest” product that solves a real customer problem. I have enough confidence in our ability to build and am willing to put my money where my mouth is.

The Solution Interview as AIDAGo big Deliver value, or go home.

AIDA is an marketing acronym for Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action. I find it a useful framework for structuring these type of solution interviews.

Attention: Get the customer’s attention with your unique value proposition – derived from the number one problem you uncovered during earlier Problem Interviews.

Interest: Use the demo to show how you will deliver your UVP and generate interest.

Desire: Then take it up a notch. When you lower sign-up friction, you make it too easy for the customer to say yes, but you are not necessarily setting yourself up to learn effectively. You need to instead secure strong customer commitments by triggering on desire. The pricing conversation above generated desire (albeit intentionally) through scarcity and prizing.

Action: Get a verbal, written, or pre-payment commitment that is appropriate. for the product above, we started taking pre-payments for the MVP and utilized a concierge MVP model to find ways to deliver continual value to our early adopters while we incrementally rolled out the MVP.

How is this Different from a Pitch?While this might look a lot like a pitch, the framing is still around learning. A pitch tends to be an all or nothing proposition. Here, you lead with a clear hypothesis at each stage and measure the customer’s reaction. If you fail to illicit the expected behavior at each stage, it’s your cue to stop and probe deeper for reasons. For instance, you might have your positioning wrong or be talking to a different customer segment.

To see all of these principles in action, watch this short case-study I presented at SXSW:

P.S.

If you don’t yet have a copy of my book, grab a copy of Running Lean here.

September 10, 2013

Why You Should Never Ask Customers What They’ll Pay

The following is an excerpt from my book: Running Lean.

Can you imagine Steve Jobs asking you what you would have been willing to pay for an iPad before it launched? Sounds ludicrous right? Yet, you’ve probably asked a customer for a “ballpark price” at some point.

Well, that’s just backwards.

Think about it for a moment.

There is no reasonable economic justification for a customer to offer anything but a low-ball figure.

They will either know the real value of your product and downplay it in order to get a good deal.

-or-

They may honestly not know and this question only makes them uncomfortable.

It is not your customer’s job to set pricing.

An optimal price is one that is accepted but not without some initial resistance. It is your job to both set that price and convince the customer. Apple is a master at this. They manage to charge a premium for their products and get people lining-up for their products.

Pricing is considered more art than science but in the next series of posts I’d like to explore tactics for demystifying how to set and test pricing.

Principle 1: Pricing is Part of the Product

Suppose I place two bottles of water in front of you and tell you that one is $0.50 and the other $2.00. Despite the fact, that you wouldn’t be able to tell them apart in a blind taste test (same enough product), you might be inclined to believe (or at least wonder) whether the more expensive water is of higher quality.

Here, the price can change your perception of the product.

Principle 2: Pricing Determines Your Customers

Pricing doesn’t just define the product but also your customers. Building on the bottled water example, we know there are viable markets at both price points. The bottle you end up picking defines the customer segment you fall in.

Principle 3: Pricing is Relative

In their seminal book on Positioning – The Battle for the Mind, Al Ries and Jack Trout describe the concept of a product ladder which is how customers organize products into a mental hierarchy. Your job is understanding what alternative products occupy the top 3 spots in their mind. These alternatives provide reference price anchors against which your offerring will be measured.

Alternatives can be real or extrapolated. In both cases, they help when applying the relativity principle.

Watch how Steve Jobs introduced pricing for the iPad in a brand new product category:

Steve Jobs skillfully anchors iPads against pundit predictions (who used netbooks for price anchors) and makes the iPad look like a steal.

I’ll talk more on how to “pitch” your price in the next post. For today, lets cover how you come up with an initial price to test.

Determining a Starting Price Through Problem InterviewsThese principles come heavily into play during problem interviews. Because pricing and product are inseparable, you should not directly bring up the price of your product until you have a clear understanding of what you are building, for who, and know what alternatives already exist.

That is precisely what you set out to learn during problem interviews with potential customers.

Lets see how this plays out in practice. One of my previous products, BoxCloud, was a file-sharing product that simplified the process of transferring large files. Now lots of people could have benefited from the underlying value proposition, but here is a sampling of what I learned from different customer segments:

Consumers

Existing Alternatives: Email, torrents, personal websites

Pain level: Nice-to-have

Price anchor: Free

Graphic Designers

Existing Alternatives: FTP servers

Pain level: Low for them, high for their clients

Price anchor: Value placed on easy setup and simple web-based interface for customers.

Attorneys

Existing Alternatives: Couriers

Pain level: High

Price anchor: $50 per transfer

I got even more varying responses from accountants, medical professionals, architects, photographers, video game designers, etc.

The same product problem and solution combination could be positioned against a dizzying array of customer segments using different channels and price points. I ultimately used two other criteria – customer pain level and ease of reach, to prioritize starting with the graphic designer segment with a $19/month starter plan. I eventually positioned BoxCloud for small-medium sized businesses and launched a separate sister-product a couple of years later to address another segment – amateur/professional photographers.

Pitching and Testing Your Price Through Solution InterviewsNext time, we’ll cover techniques for pitching and testing your price with customers or better yet “How to get your customers to want to pay even before building your product”.

P.S.

If you don’t yet have a copy of my book, grab a copy of Running Lean here.

P.P.S.

It’s chock full of lots more actionable tactics like these.

September 3, 2013

The Different Worldviews of a Startup

In his book, “All Marketers are Liars Tell Stories”, Seth Godin defines a “worldview” as the set of rules, values, beliefs, and biases people bring to a situation. He offers a strategy of not trying to change a person’s worldview but rather framing your story in terms of their pre-existing worldview.

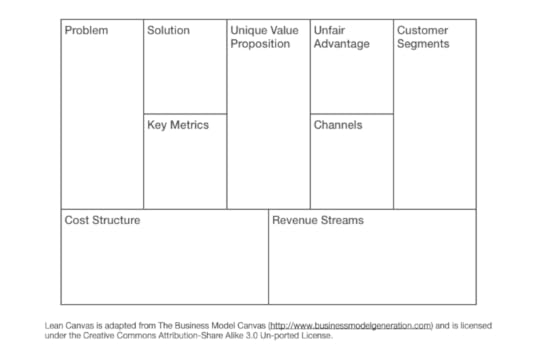

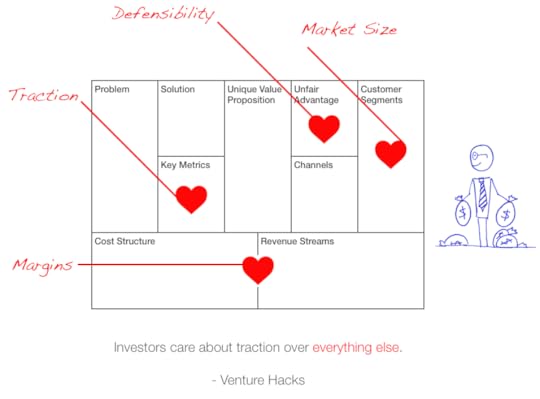

This concept of worldviews also applies to startups which I’ll illustrate using the Lean Canvas. For those unfamiliar with a Lean Canvas, it is a one-page blueprint of the basic building blocks that define your startup or product.

Different people – entrepreneurs, customers, investors, advisors, all see a startup differently.

EntrepreneursWhen entrepreneurs are hit by an idea, they are naturally drawn to the solution box and often spend a disproportionate amount of time designing or building their solution (alone). They fall in love with “awesome”. Sometimes that awesome is truly awesome for other people. Most times, however, it’s not.

This is why the solution box was made purposefully small on the canvas. It is first to encourage entrepreneurs to think in terms of the smallest thing they could possibly build to test their vision (a minimum viable product). And second, to highlight that there are eight other boxes on the canvas that are equally important (some even more important) in making their product successful.

CustomersWhen customers view your product or startup, they don’t care about your solution. They are already constantly bombarded with enough product offerrings. What gets their attention first of all is identity – do you understand who they are? Once they know you are targeting them, do you have something compelling to offer – what is your value proposition? If the first two resonate, the next thing they turn to is pricing – is it commensurate with value?

This is the worldview typically shared by early customers (or early adopters). Truly visionary customers (innovators) might be hooked just by the problem definition, while mainstream customers (early/late majority) need more social proof – a.k.a traction (Key Metrics).

InvestorsWhen investors look at your startup, they too don’t care about your solution but are weighing your startup (or business model) as an investment. The thing that matters above all else is traction. If you have good traction, you can almost always convince the right investor to write you a check. Short of that validation, investors rely on other proxies to gauge their investment risk. Investors do care about the customers you are targeting but not in terms of who they are but how many they are – market size. The next that matters is the intersection between your revenue streams and cost structure – or how you will make money. And finally your unfair advantage story or defensibility against copy-cats/competition.

AdvisorsAdvisors too bring in their own unique worldviews, but unlike the others, their worldviews are driven by their past experiences and interests. That is why it is important to surround yourself with complementary advisors and be as open and honest with them. When you simply practice “success theater” with them, while it may result in a pat on the back, it misses out on a huge opportunity for learning.

Each of the boxes in the canvas represents risks or objections you must overcome towards building a successful startup. The true job of an entrepreneur then is to systematically de-risk their startup over time. It helps to appreciate the different worldviews other people carry with them and frame your story accordingly.