Ash Maurya's Blog, page 12

May 30, 2015

Names Matter

I got tired of recycling my stacks of paper coffee cups so I got myself a reusable JOCO coffee cup which I love and so do the baristas. But they all keep referring to it as a KeepCup despite my repeated corrections.

Both brands are from Australia, and while KeepCup has been at it longer, they both were around when the eco-friendly cup trend started picking up. I confirmed this by asking the baristas when and where they first heard of a KeepCup.

The reason KeepCup is more memorable is it incorporates the job the product was hired to do. JOCO on the other hand is just a name that probably only means something to the founders.

More the reason to defer the naming of our products until we have a clear job in mind worth naming it for…

May 29, 2015

You Don’t Need Permission to Start

One objection I commonly hear is that I don’t have the right resources to start.

You may not have the right resources today to scale your idea, but I believe everyone has the right resources to start. Provided you are willing to get a little outside your comfort zone and apply a staged (versus all out) approach to rolling out your vision.

Remember your job as an entrepreneur (or intrapreneur) is to systematically de-risk your “big idea” over time.

You need to do this to attract a team who will quit their current projects to come work with you.

You need to do this to attract your earliest customers who will quit their existing alternatives for your solution.

And you need to do this to attract your external stakeholders – your investors, advisors, and key partners, who want to grow with you.

You don’t need permission from anyone to start, but you have to start.

May 28, 2015

The Singularity Moment of a Product

The singularity moment of a product is not when you write your first line of code or raise your first round of funding, but when you create your first customer. You go from nothing to creating value.

Every business whether it’s Amazon, or Google, or Facebook started this way – with one before the millions (or billions).

While one might seem too simple to strive for, it’s not.

In order to get one good customer, you need to get 10 times as many people actively using your product.

In order to get 10 active users, you need to get 10 times as many people interested in your product.

So to get 1 good customer, you need to start with at least a 100 people.

Not so easy after all…

May 27, 2015

The Secret to Breakthrough

What do all these discoveries have in common:

Penicillin, Plastics, X-rays, Gun Powder, Dynamite, Microwave, Vulcanized Rubber

They were all accidents.

Instead of throwing out their failed experiments and moving on, these scientists did something very different:

They asked why.

Breakthrough insights are usually hidden within failed experiments. As entrepreneurs, we often run away from failure and use terms like pivot to justify our sudden change in direction. But a pivot not grounded in learning is just a disguised “see what sticks” strategy.

You might get lucky but chances are high you’re NOT going to break through a certain set ceiling of achievement this way… unless like these scientists, you hunker down and get to the root cause of these failures.

Better yet, remove “failure” from your vocabulary:

“There is no such thing as a failed experiment- only unexpected outcomes. ”

– Buckminster Fuller

May 26, 2015

What Customers Want is Progress

Customers don’t care about your solution. They often don’t understand their own problems well enough to know what they really want. But what they really want is progress.

The more specific you are when describing this progress, the more they want it.

The more specific you are when diagnosing the obstacles to achieving this progress, the more they want it.

The more specific you are when comparing your solution against their alternatives, the more they want it.

That is the essence of crafting a compelling unique value proposition.

May 25, 2015

What is Strategy?

Ask a dozen people what strategy means to them and you’ll probably get a dozen different emotionally charged answers such as this one:

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.”

– Sun Tzu

The term “strategy” first appeared in modern day management theory only in the 1960s but its roots date back to ancient eastern and western military philosophy. Since then, lots has been published on strategic thinking and planning. In 1998, Henry Mintzberg proposed at least five ways of thinking of strategy: as a plan, as a pattern, as a perspective, as positioning, and as a ploy.

I would argue that while all these definitions look seemingly different, each is a further qualification of strategy by the scope of the strategic intent. To illustrate what I mean, lets start with the most basic definition of strategy as:

A high level plan to achieve one of more goals under conditions of uncertainty.

In an innovation context, the high level goal of a business model is to achieve traction. Strategy then starts out as a deliberate plan to achieve this goal.

Since all businesses share this common goal, best practices inevitably emerge and enable the refinement of the starting strategic plan through the use of patterns and perspectives. Of course, along the way new patterns and perspectives are also discovered.

Zooming in further, while patterns and perspectives are helpful guideposts, no too businesses are exactly alike. Every business needs to differentiate itself, at least from its immediate neighbors, which is where strategy is again applied – this time for positioning or as a ploy to gain a sustaining advantage.

May 24, 2015

The Space Between

“Music is the space between the notes.”

– Claude Debussy

Musicians play fewer notes than your mind actually hears.

Martial artists win or lose in the spaces between them.

Comedians create space with the pause.

Artists with white space.

This is a new experimental format for me where I’m exploring the space between ideas.

May 23, 2015

Waste is Everywhere

Taichi Ohno, the father of Toyota Production System (which later become Lean Manufacturing), is known for drawing a chalk circle on the Toyota factory floor and having managers take turns standing in the circle with the task of searching for waste in the production process. This is the process of kaizen or continuous improvement where even small reductions in waste can have significant payoffs in productivity.

“Waste is any human activity which absorbs resources but creates no value.”

– Womak and Jones, Lean Thinking

However, when applied to innovation (and life in general), the problem isn’t so much finding waste, but prioritizing waste. When operating in an environment riddled with extreme uncertainty and limited resources, it’s easy to find waste everywhere.

Pareto’s 80/20 rule applies here: 80% of the business results come from only 20% of the actions. The question, of course, is what 20%?

“The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.”

– Michael Porter

August 19, 2014

How to Test Whether Your Business Model is Worth Pursuing

Last time I emphasized getting specific on your revenue streams – down to the customer segment, pricing model, and customer lifetime assumptions.

In this post, I’m going to show you how to use these simple inputs to ballpark your business model and test whether it’s worth pursuing.

If you don’t have a “big enough” problem worth solving (that’s not even plausible on paper), then why expend any effort on it.

The traditional top-down approach for doing this is attaching your business model to a “large enough” customer segment. Then the logic goes that if you can capture “just 1%” of this large market, you’ll be all set.

After all, 1% of a billion dollar market is still a lot of zeros…

The problems with this approach are that

it gives you a false sense of comfort,

it doesn’t address how to get to this 1% market share with your specific product, and finally

1% market share might not even be the right success criteria for you.

For these reasons, I advocate a different approach.

Before you can test whether your business model is worth pursuing, you need to first ballpark the finished story benefit of your business model.

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

- Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

I know this sounds a lot like the “exit question” investors ask and I can already sense your uneasiness. Most people hate this question because it feels like arbitrarily picking yet another large number out of thin air (like a $100M exit goal) and then working excel magic to rationalize the number.

First, this number isn’t quite pulled out of thin air.

We need this number to justify the business model story – first to ourselves and then to our internal and external stakeholders (team, investors, budget gatekeepers, etc.).

$100M represents a return on investment a VC needs to justify their investment across a portfolio of highly risky startups. That said, this number doesn’t have to be $100M and is more a function of your business model incubation environment.

If instead of a startup, you were exploring a new business model in an enterprise setting, there would similarly be some expected return (one with a lot of zeros too) to justify the effort expended.

Even as a solo bootstrapper, you probably have (and if not, should have) some ballpark number to justify your return on effort per project. This could very well be a $100M exit, but could just as well also be generating an extra $1,000/mo of passive income.

There is no right or wrong answer but you should have an answer.

I’ll warn you that this can be a deep (and often uncomfortable) thought exercise that gets to your personal “why”, but the constraints it exposes allow for a more actionable strategy.

And that’s the more important message:

While we all need a ballpark destination to justify the journey, it’s not the destination itself but the starting assumptions and milestones along the way that inform whether we are on the right path or need a course-correction.

.

.

Read on to see how to make this number more actionable…

1. Determine your Minimum Success Criteria

Instead of thinking in terms of your business model’s maximum upside potential (like the 1% market share goal), I find it more helpful to think in terms of timeboxed minimum success criteria.

If, for instance, you had asked the Google or Facebook founders when they were first starting out whether they thought they would go on to build billion dollar companies, they would probably have laughed at you.

“We built it and we didn’t expect it to be a company,

we were just building this because we thought it was awesome.”

- Mark Zuckerberg

In the case of Google, we know that despite building a very successful search engine (in terms of usage), they struggled for years to find a sustainable business model and even tried to get themselves sold to yahoo for $1M which got turned down. So at that point in time, we could say that their minimum success criteria morphed from whatever it started at to $1M. That didn’t keep the google founders from going on to build a billion dollar company.

No one penalizes you for revising your goal upwards.

Not only is the minimum success criteria easier to estimate than your maximum upside potential, it also helps you model your progress along the way.

Your minimum success criteria is the smallest outcome that would deem the project a success for you X years from now.

Some notes:

1. I like to use X as 3 years and don’t recommend going over 5 years.

The key is picking a time box just far enough into the future that allows you to demonstrate a small scale working version of your business model.

2. I prefer framing the outcome in terms of a yearly revenue number versus profit or a company valuation.

Yearly revenue has fewer inputs which keeps the model simple. The others are optimized derivations of revenue. So as long as you leave yourself enough room, you should be okay.

3. Finally, the outcome does NOT have to be revenue based.

For instance, I wasn’t driven to write my book, Running Lean, by money but impact. Not-for-profit ventures also fall into this category which I’ll cover in a future post.

.

.

That said, the minimum success criteria is just a number and it’s still somewhat decoupled from the actual specifics in your business model.

Lets see how we tie the two together.

2. Convert your Minimum Success Criteria to a Customer Throughput Number

While money or revenue is easy to measure, money is a terrible measure of progress for a business model.

Here’s why:

Revenue is generally a longer customer lifecycle event

Relying solely on revenue as the measure of progress can mean flying blind for a really long time. Even if you are already generating revenue, unless you can tie back revenue to specific actions or events from the past, you can easily mislead yourself.

For instance, it’s common to see everyone in the company taking credit during a good quarter and pointing fingers during a bad quarter.

Revenue can be gamed

The danger with using money as the measure of progress is that it’s tempting to resort to accounting tricks, strategies, and policies that while good for short term cash flow may actually be detrimental to the overall long term health of your business model.

For example, it may be tempting to license your technology to a bigger company or do some custom development on the side. But if these don’t represent repeatable actions in your business model, they may be one-off cash flow events that distract you from building a scalable model.

.

.

The answer to the problems above is deconstructing your revenue goal into it’s constituent customer throughput metrics.

While revenue can be gamed, it’s harder to game customer behavior.

We can model customer behavior using the sub-steps from the customer factory diagram below:

You’ll see that while revenue is one of these metrics, there are other metrics that come before revenue. These metrics, like retention/engagement, can serve as leading indicators for revenue and more effectively used as a measure progress.

Additionally, by tying back revenue to these leading customer behavior metrics, you avoid the short term gaming and accounting tricks from earlier.

These leading indicators, by the way, also hold the key to modeling multi-sided business models that I’ll cover next time.

But for now, lets keep this simple and see how we can use the simple inputs from your Lean Canvas combined with your minimum success criteria to test whether you have a business model worth pursuing.

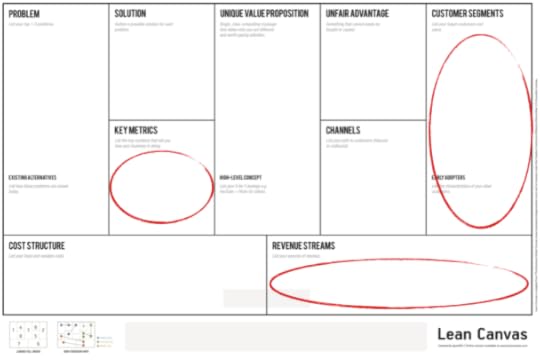

Consider the following Lean Canvas from one of my software products:

The critical inputs I need from the Lean Canvas are:

Goal = $10M/yr revenue

LTV = $200/mo * 2 years = $4,800

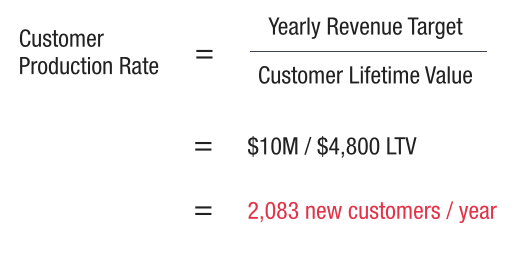

The first number I need to calculate is the customer throughput or production rate that I will need to to sustain my model at scale. In other words, I am going to treat the customer factory as a black box for now and only focus on it’s output.

I want to know how many customers I need to continually produce (on the right) to sustain my $10M/yr revenue goal.

Here’s the simple math to do this:

Make sure you work the numbers out for yourself before moving on…

In my workshops, people have no problem calculating the number of active customers needed for $10M/yr revenue which in this case works out to to 4,167 active customers. But the 2,083 new customers/yr isn’t the number of active customers but the number of new customers you need to create in your business model every year to replace older customers that leave due to churn.

Later we’ll model the internals of the customer factory, but this output customer production rate is enough to serve as your first dose of reality for your business model.

3. Test/Refine Your Business Model Against Your Minimum Success Criteria

The purpose of this simple back-of-the-envelope calculation is to turn a big fuzzy revenue number into something real and tangible – like creating customers.

All metrics are people first.

It’s much easier to do a gut test with people than just with numbers. You can now revisit your Lean Canvas and put your customer segment and channel assumptions to test.

How does having to add ~2,000 new customers every year make you feel?

Is your customer segment big enough?

Do you have any scalable channels identified already for building a significant enough path to customers?

The business model above targets SaaS companies as early adopters and more general software companies as the total addressable market at scale. So for me, the 2000 customer production rate doesn’t immediately freak me out.

During a workshop in Paris, however, I ran through a similar exercise with an entrepreneur who intended on charging €5/mo for his product with a 2 year projected customer lifetime and a €5M/yr revenue goal.

Here the math worked out to having to add 40,000+ new customers every year!

This simple math invalidated his model because there weren’t even that many potential customers in all of France.

The solution to this problem is pretty straightforward.

First, you might try growing your customer segment. We had a short discussion on market size. The entrepreneur was already contemplating expansion to other countries. Those plans would need to be accelerated if nothing else was done.

The other options for lowering your required customer production rate are obvious from the formula:

You can either lower your yearly revenue target or raise your customer lifetime value.

Assuming, we don’t want to lower our yearly revenue target (just yet), the way you increase your customer lifetime value is either by increasing your customer life term or raising prices.

1. Increasing your customer life term

Doubling your customer life term from 2 years to 4 years would half your customer product rate. That said, increasing customer life term is non-trivial because it potentially requires you to revamp your value proposition and product.

2. Raising prices

This is by far the most powerful (and under utilized) lever you have in your business model. Doubling pricing from €5/mo to €10/mo also cuts the required customer production rate in half. But unlike increasing life term, a price change may only take a few minutes to implement on your checkout page.

Sure, there is always the danger that increasing pricing will result in fewer customers but what if it doesn’t?

If you could double your pricing, and not lose more than half your customers, you still come out ahead.

I’ll get into why in a future post.

Isn’t this all just funny math anyway?

At this point, you might be wondering whether all this is even worth the trouble. After all, you can easily double or quadruple the pricing model on paper to make the model work. So what?

Let’s go back to this statement from earlier:

While we all need a ballpark destination to justify the journey, it’s not the destination itself but the starting assumptions and milestones along the way that inform whether we are on the right path or need a course-correction.

We started with a big fuzzy money goal (the destination) and first converted it into a customer throughput number. We then further deconstructed this number into a set of input parameters (starting assumptions) that can actually be measured from day one.

While quadrupling your price might have been easy on paper, if you can’t get outside the building and find 10 people that will accept that price (first milestone), then you have a problem!

You don’t need 3 years to figure this out.

Getting accurate customer life time value numbers requires more time. But here also, you can begin to extrapolate customer lifetime value using secondary approximations (like your monthly churn rate). You don’t have to wait the full customer life time to estimate your customer life time value.

Like scientists, our job as entrepreneurs is to first build a model and then test that model through experiments.

If the experiment fails, we need to either adjust the model or more likely adjust the input assumptions into that model.

“It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.”

- Richard P. Feynman

August 12, 2014

There is No Business Model Without Revenue

I created the Lean Canvas back in 2009 as a way to more effectively document my most critical business model assumptions for my products which were predominantly SaaS software products at the time.

Lean Canvas is now taught at over 200 universities (including high schools), close to 100 startup accelerators, and used at hundreds of businesses (including large enterprises). We just crossed the 125K users and 175K canvases mark with our online Lean Canvas tool.

I’m not sharing these numbers to show off our vanity metrics but rather to acknowledge that both the scope of usage and audience has broadened well beyond my prototypical early adopter. Just the other day I got a Lean Canvas question from a salmon fisher in Chile!

But with expansion comes challenge.

In this case, one of adapting and refining the framework beyond it’s original reference model. I’ve mostly been addressing these challenges in my private workshops and bootcamps and noticed that I haven’t posted any of this publicly.

This was brought to a head for me recently after reading a post by Benjamin Kampmann titled: The Lean Canvas: Wrong Tool for the Job where he recounts several issues he faced when modeling his tech-ventures with the canvas.

First, I’d like to thank Ben for posting his experiences publicly. I’ll attempt to address his concerns along with others I’ve collected along the way in this post and follow-on posts.

The core issue Ben raised stemmed from a characterization that the Lean Canvas was too focused on profit as the main goal of any venture. He further argues that this profit seeking focus derails ventures that fall outside the direct (user = customer) reference business model such as in multi-sided models and not-for-profit models.

While I don’t like to think of money solely as the goal of a business, I liken money to oxygen.

We don’t live for oxygen, but we need oxygen to live.

That said, there is a difference between money and profit. And I don’t consider profit the universal goal of every business or product.

The Universal Goal of Any BusinessThe universal goal of every business is to make happy customers.

Happy customers get you paid and doing this repeatedly and sustainably is the goal of every business.

This is true whether you are building a product business or a services business,software or hardware, low tech or high tech, and even if you are building a for profit or a non-profit business.

This, by the way, is also the central theme of my next book, not co-incidentally, titled: “The Customer Factory”.

I am not going to dive into the details of the Customer Factory in this post, but rather use this central idea to show you how you can use it to model any type of business with the Lean Canvas.

My guess is that this profit-seeking characterization is rooted in the presence of a prominent Revenue Streams box on the canvas which poses problems when thinking about some of these non-direct models.

First, the happy customer goal isn’t a cop out for not being specific on your revenue streams which is a problem I see generally across all canvases I review – even direct, for-profit models.

“There is no business in your business model without revenue streams.”

For that reason, I want to kick off with the simplest (not necessarily easiest) direct, for-profit, business model and then build up from there in subsequent posts.

By specific, I don’t just mean citing your revenue stream sources but getting down to actual pricing and projected lifetime numbers.

For example, $50/mo with 2 yr lifetime.

You need these numbers to ballpark the opportunity or “problem worth solving” both for yourself and for your external stakeholders. If you don’t have a “big enough” problem worth solving (that’s not even plausible on paper) then why expend any effort on it.

I’ll cover the simple math for ballparking your business model next time.

The biggest objections I hear against being this specific are:

a. How do I price a product when my solution is still uncertain?

Customers care about their problems and not your solution.

So you should price against their problems (using value based pricing) and not what it’s going to cost you to build and deliver your solution (that’s a Cost Structure concern). You do this by anchoring against their Existing Alternatives where you should ideally be able to point to some evidence of monetizable pain.

The best evidence of monetizable pain is a check being written but there are other proxies.

b. How do I estimate my customer lifetime?

This one is a bit harder to model but it’s still an important input assumption to document. While we would all like to keep our customers forever, every business has non-zero churn or some finite customer lifetime – sometimes because they hate your product so much that they leave, and sometimes because they love your product so much that they use it to solve their problem and then move on.

One way to guess at the customer lifetime is through the nature of the problem you are solving. Is it a single occurrence problem or something recurring? If recurring, how frequently would the user need to solve the problem and for how long. From there you might be able to guess when they would outgrow your solution.

Studying other analogs in your vertical or domain can also be an effective way for estimating your average customer lifetime. If all else fails, pick a conservative estimate for now. You’ll get an opportunity to understand the impact of this number in the ballparking exercise that I’ll cover next time.

c. What if I have multiple customer segments?

Keeping your pricing model as simple as possible, especially at the earlier stages, not only helps with ballparking but also with faster validation of your business model.

I recommend starting with a single price modeled after your early adopters. Your early adopters represent your best first customers and should also represent a “significant enough” initial beachhead of customers. The thinking here is that if you can’t get these guys to accept your pricing model, what chance do you have with your other segments?

If you are further along or still insist on pursuing multiple customer segments, then come up with an average price per customer using some simple customer segment distribution model.

d. What if I’m giving away my product for free?

There is no business model in free. I have a whole chapter in my book, Running Lean, on why I consider Freemium to be a bad starting model.

Instead start with the premium part of freemium and then use free as a marketing tactic to fill up your customer acquisition pipeline.

Delaying price testing, delays testing one of the more riskier parts of your business model. Plus your pricing model does a lot more for your product than just put money in your pocket.

.

.

Ok, so you’re probably thinking all this still applies to direct business models.

How does this help with the other models?

Lets start with a definition of a business model that I particularly like:

“A business model is a story about how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value.”

- Saul Kaplan, The Business Model Innovation Factory

You create value for your users through your Unique Value Proposition which you deliver through your Solution and when you capture some of this value back through your Revenue Streams you make customers.

It’s simpler to tell this story with the direct business model because it’s a 1-Actor model where your users become your customers.

The other models are multi-actor models which complicate the story telling part a bit but every business needs to be able to tell this story.

We’ll pick up next time with multi-sided business models and then move on to not-for-profit business models from there.

But before you go, I’d love for you to hit that Facebook like button below if you found this content helpful.

But more importantly, I’d like you to leave a comment. I want to hear from you. What’s your challenge or issue modeling your business with Lean Canvas?

I’m going to be reading every one of these comments and responding to as many as I can.

So scroll on down and leave a comment.

Until next time…Take care.

Let me know what you think…

Let me know what you think…

Please leave a comment for me below (and then go ahead and hit that Like button!)