L.E. Henderson's Blog, page 21

September 14, 2014

"Your writing is not what we are looking for." Why I do not want it to be:

I learned about this wall when, right out of college, I sent out a bundle of hopeful article submissions and they, all except for one, bounced against the hard brick surface. I finally did get published and paid.

But exhaustion dampened the thrill. The reward was not nearly worth the amount of time and effort. Aspiring writers are instructed to keep trying no matter what the obstacles are so that, eventually, they will reap the long-sought rewards of editorial approval, a proud but probably meager paycheck, and the right to say, “Look. I was published.”

That common advice highlights to me how bleak and – sometimes demeaning – the landscape of traditional publishing is for writers. Many writers will put up with almost anything because the market is so flooded with those who dream of writing for a living, individuals writers have little leverage, regardless of their talent.

But I wanted to write. Had to write. Around the turn of the millennium, I had written my first novel and was eager to share it. Someone told me about something called print-on-demand publishing, an affordable way to self-publish. The dream of holding in my hand a novel I had written was within view. The no-headache, no-waiting, and no-rejection option appealed to me. It gave me a wonderful sense of being in control.

Overall, self-publishing was a great experience and I got a lot of glowing comments. But I never marketed my book much because, not long afterward, I had a severe manic episode that led to my diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

My retreating mania sprung me into a severe depression that left me blocked for over three years. I have already written about this in my blog and my book A Trail of Crumbs to Creative Freedom but I will recap it here.

Despite being blocked, I finally decided I was going to write anyway. I was going to force what was not coming naturally anymore even if the result was terrible. This effort was tedious. I was punishingly self-critical. I stared at the clock a lot. And the writing always came with an ache for how things used to be.

One day I could not get over the feeling that I was wasting my time in a way that was doing nothing to improve my writing and that was, instead, hurting me. What I was doing, the forcing, was not working. But the inspiration that had once made writing rewarding seemed forever lost.

I could not go on the way I was. I was either going to have to give up trying to do something I had once loved, or somehow change.

I did not know how to change, so I was seriously considering quitting writing and devoting my life to video games. But that kind of loss felt like death to me.

From somewhere inside me, a protest arose. Perhaps it was a tantrum from my inner eleven year old who had loved writing, and who saw in the act of writing a treasure that exceeded payment or any kind of approval from anyone.

For whatever reason, this impulse mutinied against the obstacles that had risen up against that natural early flow: the fear of making mistakes; the attempt to please the critics in my head; and the need for editorial authorities to validate my efforts.

My sensible inner “eleven year old” knew that she had been good at writing once. She had loved writing during times of terrible stress where writing had been the best thing in her life.

I credit her with shedding the fear that was blocking me. From that point I gave up forcing my writing. I gave up trying to write how others had said I was supposed to write.

I was going to go back to writing for fun. I was going to be recklessly silly if I felt like it, use trite expressions according to my whim, wallow in self-indulgence if I pleased, and anyone who disapproved could return to their creepy attic full of rulebooks and sneer at cobwebs.

In a childish way, it was like saying, “Mine. Writing is mine, not theirs.” And it changed everything.

I have had many pseudo-epiphanies and few truly life-changing moments, but the shift that happened on that day endured. To this day I do not have to force myself to write, and I stopped experiencing writing-induced mood crashes.

Because I was having fun, because I owned my writing, I wrote more, which made me a better writer. I was willing to go to any length to realize a creative vision that was my own.

After recovering from block and depression, I finished my second novel and began my blog. I also did some on-line freelancing and wrote my e-book A Trail of Crumbs to Creative Freedom about my escape from being blocked. I wrote it not just to share it with others, but to make sure I never forgot the lessons that had dug me out of creative drought.

I was in such a state of bliss that I could write again, I did not mind that I was earning little from it. For the first time in years, I felt like myself. I could have been content with just that, being able to access a part of my brain that had seemed closed off from me.

But I liked getting responses from readers. On the advice of someone I knew, I began posting my writing to the media hub Reddit. I wrote about ants and free speech and agnosticism. I wrote about my block and the shift in my thinking. I wrote about what had confused me about writing advice. I wrote as honestly as I could and the responses were overwhelmingly positive.

Many told me that what I wrote inspired them. I was thrilled. All the encouragement seemed to confirm that when I wrote what I loved and was honest, readers responded strongly.

Unfortunately my blog was expelled from Reddit because I was inadvertently breaking an unwritten rule against posting only my own work. But the experience of writing for a large audience who said “I like what you are doing. Keep going” made me think I really could write for a living.

I wanted to make a career out of writing so that I could do it forever, and the same is true now. Since I am more confident in my abilities than I used to be, I am now querying for agent representation to publish my new novel traditionally.

But once again I face the editorial wall. It has not changed. My queries bounce back at me and bop me on the nose. Again I am told that editors and agents are busy people who are “swamped” with submissions, most of which are dumped into a “slush pile.”

I am told that I should do extensive research to find out how to please them; that I should make my writing conform to a certain “editorial voice”; that I should include a note in my query comparing my book to a previous success they admire; and that I should look at previous books they have published to better understand what they are “looking for.”

I have a problem with my writing being what anyone is looking for.

At one time no one was looking for science fiction; it did not exist. And not long ago, paranormal romance was not a genre. No one was looking for it either. At one point an agent or publisher had to say, “This is not what I was looking for but I like this enough to take a chance on it.”

I am looking for an agent or publisher who is not “looking for” anything.

Rather than delivering the expected, I want to capture in words an image I have never seen described or tell a story I have never heard. I want to write well.

But querying makes me realize how much pressure there is to fit into an editorial mold, and I have to avoid asking the question, “How do I become what the agent is looking for?”

I seem to have come full circle, returned to the crossroads that led to my fateful decision years ago, to write for myself. It was the right decision then, and I cannot imagine myself making a different one now.

I sometimes wonder if what is behind The Wall is worth playing a game built on the premise I write to make industry “experts” happy. The philosophy that restored me to myself and has elicited such an enthusiastic response from readers runs counter to the “please at all costs” protocol of traditional publishing.

The source of my creativity, my skill, and my focus while writing has been my determination to remain myself.

The role of a writer is not to flesh out a template that already exists in the mind of an agent or editor. The best writing fulfills by surprising.

And if I have to self-publish again in order to accomplish that, I will.

"Your writing is not what we are looking for." Why I do not want it to

be:

I learned about this wall when, right out of college, I sent out a bundle of hopeful article submissions and they, all except for one, bounced against the hard brick surface. I finally did get published and paid.

But exhaustion dampened the thrill. The reward was not nearly worth the amount of time and effort. Aspiring writers are instructed to keep trying no matter what the obstacles are so that, eventually, they will reap the long-sought rewards of editorial approval, a proud but probably meager paycheck, and the right to say, “Look. I was published.”

That common advice highlights to me how bleak and – sometimes demeaning – the landscape of traditional publishing is for writers. Many writers will put up with almost anything because the market is so flooded with those who dream of writing for a living, individuals writers have little leverage, regardless of their talent.

But I wanted to write. Had to write. Around the turn of the millennium, I had written my first novel and was eager to share it. Someone told me about something called print-on-demand publishing, an affordable way to self-publish. The dream of holding in my hand a novel I had written was within view. The no-headache, no-waiting, and no-rejection option appealed to me. It gave me a wonderful sense of being in control.

Overall, self-publishing was a great experience and I got a lot of glowing comments. But I never marketed my book much because, not long afterward, I had a severe manic episode that led to my diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

My retreating mania sprung me into a severe depression that left me blocked for over three years. I have already written about this in my blog and my book A Trail of Crumbs to Creative Freedom but I will recap it here.

Despite being blocked, I finally decided I was going to write anyway. I was going to force what was not coming naturally anymore even if the result was terrible. This effort was tedious. I was punishingly self-critical. I stared at the clock a lot. And the writing always came with an ache for how things used to be.

One day I could not get over the feeling that I was wasting my time in a way that was doing nothing to improve my writing and that was, instead, hurting me. What I was doing, the forcing, was not working. But the inspiration that had once made writing rewarding seemed forever lost.

I could not go on the way I was. I was either going to have to give up trying to do something I had once loved, or somehow change.

I did not know how to change, so I was seriously considering quitting writing and devoting my life to video games. But that kind of loss felt like death to me.

From somewhere inside me, a protest arose. Perhaps it was a tantrum from my inner eleven year old who had loved writing, and who saw in the act of writing a treasure that exceeded payment or any kind of approval from anyone.

For whatever reason, this impulse mutinied against the obstacles that had risen up against that natural early flow: the fear of making mistakes; the attempt to please the critics in my head; and the need for editorial authorities to validate my efforts.

My sensible inner “eleven year old” knew that she had been good at writing once. She had loved writing during times of terrible stress where writing had been the best thing in her life.

I credit her with shedding the fear that was blocking me. From that point I gave up forcing my writing. I gave up trying to write how others had said I was supposed to write.

I was going to go back to writing for fun. I was going to be recklessly silly if I felt like it, use trite expressions according to my whim, wallow in self-indulgence if I pleased, and anyone who disapproved could return to their creepy attic full of rulebooks and sneer at cobwebs.

In a childish way, it was like saying, “Mine. Writing is mine, not theirs.” And it changed everything.

I have had many pseudo-epiphanies and few truly life-changing moments, but the shift that happened on that day endured. To this day I do not have to force myself to write, and I stopped experiencing writing-induced mood crashes.

Because I was having fun, because I owned my writing, I wrote more, which made me a better writer. I was willing to go to any length to realize a creative vision that was my own.

After recovering from block and depression, I finished my second novel and began my blog. I also did some on-line freelancing and wrote my e-book A Trail of Crumbs to Creative Freedom about my escape from being blocked. I wrote it not just to share it with others, but to make sure I never forgot the lessons that had dug me out of creative drought.

I was in such a state of bliss that I could write again, I did not mind that I was earning little from it. For the first time in years, I felt like myself. I could have been content with just that, being able to access a part of my brain that had seemed closed off from me.

But I liked getting responses from readers. On the advice of someone I knew, I began posting my writing to the media hub Reddit. I wrote about ants and free speech and agnosticism. I wrote about my block and the shift in my thinking. I wrote about what had confused me about writing advice. I wrote as honestly as I could and the responses were overwhelmingly positive.

Many told me that what I wrote inspired them. I was thrilled. All the encouragement seemed to confirm that when I wrote what I loved and was honest, readers responded strongly.

Unfortunately my blog was expelled from Reddit because I was inadvertently breaking an unwritten rule against posting only my own work. But the experience of writing for a large audience who said “I like what you are doing. Keep going” made me think I really could write for a living.

I wanted to make a career out of writing so that I could do it forever, and the same is true now. Since I am more confident in my abilities than I used to be, I am now querying for agent representation to publish my new novel traditionally.

But once again I face the editorial wall. It has not changed. My queries bounce back at me and bop me on the nose. Again I am told that editors and agents are busy people who are “swamped” with submissions, most of which are dumped into a “slush pile.”

I am told that I should do extensive research to find out how to please them; that I should make my writing conform to a certain "editorial voice"; that I should include a note in my query comparing my book to a previous success they admire; and that I should look at previous books they have published to better understand what they are “looking for.”

I have a problem with my writing being what anyone is looking for.

At one time no one was looking for science fiction; it did not exist. And not long ago, paranormal romance was not a genre. No one was looking for it either. At one point an agent or publisher had to say, “This is not what I was looking for but I like this enough to take a chance on it.”

I am looking for an agent or publisher who is not “looking for” anything.

Rather than delivering the expected, I want to capture in words an image I have never seen described or tell a story I have never heard. I want to write well.

But querying makes me realize how much pressure there is to fit into an editorial mold, and I have to avoid asking the question, “How do I become what the agent is looking for?”

I seem to have come full circle, returned to the crossroads that led to my fateful decision years ago, to write for myself. It was the right decision then, and I cannot imagine myself making a different one now.

I sometimes wonder if what is behind The Wall is worth playing a game built on the premise I write to make industry "experts" happy. The philosophy that restored me to myself and has elicited such an enthusiastic response from readers runs counter to the “please at all costs” protocol of traditional publishing.

The source of my creativity, my skill, and my focus while writing has been my determination to remain myself.

The role of a writer is not to flesh out a template that already exists in the mind of an agent or editor. The best writing fulfills by surprising.

And if I have to self-publish again in order to accomplish that, I will.

September 4, 2014

Using the Psychology of Resistance for Vivid Narrative Writing

So basic that when you touch something, the electrons in your hand repel the electrons of the touched surface. When you push an object, it pushes back: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

This is one reason resistance creates a sense of realism in fiction. Writing instructors talk about how conflict is indispensable as a way to create drama, and they are right. But I have rarely seen resistance discussed as a way to make the illusion of fiction seem more real.

If you tell a reader, “A bar of soap rested in the soap dish,” the reader can picture that. But if a character grabs a bar of soap and it slips through her hand, splashes into the water of a tub, and bangs her knee, and makes the character say, “ow,” that soap becomes real in the mind of the reader.

To give another example: In a fiction story, you could say “She moved the dining table across the room.”

This is fine if the detail is only a side-note to the drama. But suppose that a character is trying to move the table for a dramatic purpose like blocking a door to protect herself from a crazed assailant. Imagine that, while moving the table across the room, is so heavy, it will barely budge. When it does move, it scrapes the hard floor or catches the edge of the carpet.

Suppose that the protagonist is forced to move one side and then the other a tiny bit at a time. What if the splintering wooden surface pricks the hand of a character and she gasps?

In this situation the table becomes a mini-antagonist. Not only do these details of resistance tighten suspense; to the reader that table will probably seem so real he can almost touch it.

The more fanciful the story, the more the writer needs resistance, along with vivid sensory details, to pin the fiction to reality, to make the dream-like details more tangible.

However, dramatic resistance goes beyond mere touch. I had this thought while reading a Harry Potter novel. I was at the part where Harry is at the house of the Weasleys and Mrs. Weasley points out the garden gnomes to him.

They are stupid, they gnaw on plant roots, they damage gardens, and they are in the way. In order to get rid of them, Harry is informed, you have to grab them, spin them, make them dizzy, and toss them over the fence. Sometimes they escape and you have to chase them.

When reading this I thought, “What better way to make a fantastic creature seem real than to make it annoying?” No one has ever seen a live gnome, but most people have had experience with annoying animals, from biting insects to overly-aggressive but playful dogs.

Besides sabotaging a garden, the gnomes have to be engaged physically by grabbing and spinning, which makes them so tangible that, at the time I was reading, I could almost imagine that they were in the living room with me.

Had Rowling presented only a static image by saying that the gnomes had potato-like bodies, I could have pictured them, but the sense of tangibility that comes from tossing a resistant and dizzy gnome over a fence against its will would not have engaged me in the same way.

The same is true of most anything I describe in my fiction. If something balks, if it struggles, if it resists, if it is in the way, it seems more real.

This is because real life is filled with frustrations great and small. A cat bites your thumb when you try to force her into her pet carrier. On certain hot summer days, the wheel of a car is too hot to touch. Torrential rain drenches your sweater and obscures the path ahead.

From the need for conflict that is the basis of all drama to the smallest tussle with a household object, resistance is a fundamental experience of living in the physical world. And because it is so basic to life, it is also basic to the art of writing, which needs to mirror reality enough that the unreal seems possible.

Resistance pulls the fanciful from the topmost arc of a rainbow and turns it into something that the eye can see and the hand can grasp. The hassles of everyday life, while unpleasant to deal with, become gold to a writer seeking to create an illusion than convinces and compels.

September 2, 2014

Why do I not "talk myself out of" my bipolar moods?

"You are not even trying to feel better."

"I have bipolar disorder. It is not about trying"

"Yeah, but you take medication for it now. Just explain to yourself. Tell yourself why your feelings are irrational and they'll go away."

Irrational. The word stings. I like to think I am rational. I even included the word "skeptic" in my Twitter bio. In my blog I have extolled the power of critical thinking. I read Isaac Asimov and Richard Dawkins. The name of my blog is "Passionate Reason." I like reason. Reason is good; irrationality bad.

Being accused of not being reasonable makes me want to explain what it is really like to have bipolar disorder and why I cannot simply talk myself out of my moods as I am so often instructed to do.

A passage of one of my favorite books A Separate Peace is a good place to start. There is a phrase he used to describe a way that "feelings become deeper than thought."

The entire passage goes like this: "In the deep, tacit way that feeling becomes deeper than thought, I had always felt that the Devon School came into existence the day I entered it, was vibrantly real while I was a student there, and then blinked out like a candle the day I left."

That idea that feelings can become deeper than thoughts has stayed with me. There seems to be a layer of me that eludes conscious control. Some call this the subconscious, yet I am aware of it as John Knowles was, so how "sub" can it actually be?

I am very often aware of how irrational some of my thoughts are as I am having them. They seem to erupt from me, and sometimes they surprise me. For example, right after I publish a blog I have a series of "what if" moments.

What if everyone hates it, what if it contains something embarrassing I did not intend to say, what if it ruins my life and everyone hates me and I am banished to the wilderness to survive on wild berries and ant dung?

Sometimes I write these thoughts down as a way to capture and study them. Sometimes it seems that I am not really thinking these thoughts at all, but that they are a strident background music to my conscious musings, the type of irritant where I should be able to yell, "Hey, turn that down or I will call the police!"

On a purely conscious level I know better than to worry about what anyone thinks about my writing. Writing is a risk. Even it was true that everyone hated my writing, I should be able to handle it. The philosophy that released me from creative block was that I would write for myself and not worry about what anyone thought. It transformed how I worked, cured me of block, and allowed me to make friends with my writing again, so that I never have to force myself to write anymore.

Unfortunately, my ease with writing has not increased my comfort with sharing my work. I have similar anxieties about sharing that I used to have about writing, including, sometimes, mood crashes. And no matter how eloquently I explain to myself how unwarranted they are, I simply cannot make them go away. They have to run their course.

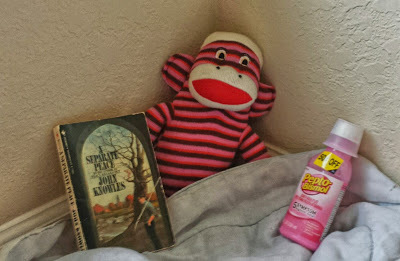

The insidious thing about bipolar disorder for me is that when I am having my moods, I do not think about them as part of a disorder. I relate my moods to a trigger: "My blog had a glaring typo that changed the whole meaning of my sentence, but people have already seen it. Alas! I must retreat to my sulking corner at once with a snuggly blanket, a sock monkey, and a vat of Pepto Bismol."

However, I am often aware that the triggering event often does not warrant the level of emotional discomfort that I feel. Having my cat get sick on the carpet should not ruin my day or cause me to question the meaning of life and the root of all suffering.

I know this, and the discrepancy between what I know and what I feel causes me agonies of cognitive dissonance.

But my discomfort does not just stay in my head. It affects the decisions I make during the day. It influences what I do.

When planning my afternoon activities I find myself scanning possibilities as cautiously as I would in a mine field, alert to anything that might trigger a mood crash. Fortunately, the act of writing causes me no pain unless I am getting ready to share it.

Writing is therapy for me. It focuses and relaxes me. Usually it improves my mood, although that was certainly not always the case.

But querying is a different matter. How it will affect my mood is unpredictable. By querying, I am giving someone the power to reject me. It is an exposed feeling and, in order to make this uncomfortable risk a reality, I am doing tedious work in order to conform to varying formatting and word count requirements.

There is no certainty that anything will come of any of them. The pull of wanting to write, to create something instead of trying to impress a stranger, is sometimes overwhelming. Querying can and often does make me remember what it feels like to be depressed. Because of that, I have to resist powerful impulses to avoid it.

But is avoiding mood-dimming activities strictly the domain of someone with bipolar disorder? Most everyone seeks to avoid unpleasant activities. This leads to another question that I frequently ask myself: How many of my bad moods are normal? Which of them are induced by illness? Where does my pathology leave off and where do I begin?

Are feelings being out of sync with a situation a result of bipolar disorder or is it a human problem?

There is no clear line between my "healthy" personality and my illness-induced moods. There is no single site that a physician can point to and say "There is your bipolar disorder, right there. Got a scalpel and some tongs? I can get that Bad Boy out in two shakes of a lamb's tail." Whatever bipolar disorder is, I suspect it is wired into my brain in a way that is complex, burrowing into the folds and fissures where my personality is.

The medication I take is effective in preventing major episodes, but it is not infallible. But telling this to someone who has never suffered from mental illness can be difficult. The idea that I cannot talk myself out of a mood inappropriate to a situation strikes deep at what some people want to believe about free will.

But I wonder: If people could feel the way they chose, why would anyone ever take drugs, illegal or otherwise? There is something strange about trying to control my mind with my mind, and particularly with trying to assuage an afflicted mind with an afflicted mind.

However, I think that sometimes it can actually work, which is why it is so tempting to think I could make it work all the time. I thought my way out of being blocked creatively. I talked myself out of it to a degree that I do not struggle with it anymore. I even wrote a book about it.

I am intrigued with the idea that I could apply the same principles I used in getting over my block to also overcome my anxiety about sharing my ideas. Would it work? In writing the change came through a kind of rebellion about not having to please anyone anymore. I defanged my internal censor by creating a "therapy" file in which I heaped praise on myself to counter all the self-doubts that arose. And in doing so I changed the way I think about writing in a way that endures.

That is one reason I am so frustrated that I am still subject to the whims of my mood cycle. There are times my mood nosedives for no good reason, and when I am in that state, my ability to talk myself out of my depression is impaired by the depression itself. It is hard for a broken mind to repair itself and meanwhile pain gushes into the gaps where reason used to be.

I am not willing to say that my illness strips me of free will. But the place inside me where feeling become deeper than thought sometimes sinks beyond the reach of logic, pep talks and platitudes.

Can I control my moods to make them conform to the situation? Yes and no. There are times I have done it, when I went into myself and dug up treasure, insights that changed my perspective and that I could apply.

But when the rising tide of depression gets too far over my head, I go into auto-pilot. I react instead of act, and my higher cerebral functions go off-line. When this happens it is no help at all for someone to say, "Just be reasonable."

I believe this is why a combination of drugs and psychotherapy are normally used to treat mental illness. People are able to adapt to a degree and have some control but there are limits.

Drugs address the biological facet of mental illness, but steering through a confusing hurricane of moods sometimes needs guidance.

I am not sure what I need. For me, writing is more effective as therapy than any psychiatrist I have ever been to, and, despite my complaints, I consider myself happy overall. Feeling truly depressed is a relatively rare occurrence now, but on days it appears, it is no less alarming than it ever has been.

I want to be in control of myself. I want my moods to be commensurate with the events that trigger them. But regardless of how much control over my moods I do or do not have, I wish people would stop saying, "You are not trying to feel better."

I believe that when people say that, they are trying to confirm a model of human behavior that comforts them, one that says, "If someone is unhappy, it is their own fault; they have probably made poor decisions; they are too passive; they are not even trying to improve their life."

Someone who cannot see the world through my eyes has no basis for saying whether I am trying or not. Why would I choose to be unhappy? It is a ridiculous accusation.

And it simply is not true.

August 27, 2014

Writing: A Methodical Way to Dream

I tensed because I knew what was coming. “Art,” I said.

He laughed, and a few students joined in. He shrugged and sighed. “Guess it takes all kinds to make a world.”

His amusement illustrates a perception that art is frivolous compared to academic subjects; or that a cerebral mindset inhabits a more respectable realm opposite the free-flowing state of imagination.

But creative endeavors like art are mentally intense because they require both processes; however, there does seem to be an uneasy partnership between the two. Maybe that is is why, for such a long time, I was so confused about the process of writing, which requires melding imagination with planning and analysis.

I used to think writing was just supposed "to happen." Professional writers talked about characters that sprang to life on the page and acted on their own. They often described writing as a near-mystical state where everything just “comes together.”

I had had experiences like this, moments when something seemed to “take over,” and sometimes the writing was effortlessly good. Afterward I would be afraid to touch it, even when it had clear flaws. It seemed almost sacrilegious to impose my analytic self on the creative spontaneity that had occurred under the influence of the elusive muse. Why mess with magic?

Well, for one thing, “magic” is not real, and art produced purely by accident is not art.

But I had noticed that whenever I started to plan or write a plot for my stories, my excitement fizzled. Whenever I just “let writing happen,” it was more likely to have fresh imagery but it was usually not cohesive. The two methods of approaching creative writing, structural planning and dreaming, seemed to be in conflict with each other.

For planning, I was used to writing outlines for school, so for fiction I would always start there, but when I did, creative inspiration became elusive.

A turning point happened for me when I realized that creative problem solving needs to be approached in a different way than you solve, say, a math problem.

I had thought plotting was purely cerebral since it involved planning and sequencing. But plotting fiction is a creative task rather than a strictly linear, left-brained one.

Before, whenever I worked on a plot outline and a question came up, I would always go with the first answer that came to me. Question: After Sally is fired, what does she do? Answer: she looks for another job.

There is nothing wrong with this answer and it is perfectly logical. But what I needed to be doing was generating multiple options, good or bad, so I could choose. “Sally stays home, sulks, and binges on ice-cream. Or Sally steals from her mom. Or Sally pawns her wedding ring.”

Generating multiple ideas to choose from engages the artist in me. As in math, the ultimate goal is to reach a single solution, but art is about making choices. For that, multiple options are needed.

To me there is no better tool for generating multiple options a technique called clustering.

I learned this method from Natalie Rico in her book Writing the Natural Way. Clustering begins with an idea, which can be anything: a color such as blue or an idea such as “anger.”

You write the word down, circle it, and free-associate, drawing a line from the center that leads to the new idea. From anger an association might be “fire.” Then “fire” might become the next center from which to free-associate: “hell,” which carries religious associations. Or it could be “hot chocolate,” which may transport me to a memory of “snow.” Repeating this process a number of times to creates a radial web of ideas.

The associations may or may not seem logical. There is no wrong way to cluster, and knowing that creates the relaxed state of mind conducive to creativity.

After I cluster for a while, something in my brain will usually “click” and I will know exactly what I want to write. Usually I feel excited.

Clustering generates many ideas, which is a good thing because art is about saying “I like this better than that.” The more ideas you have, the more you increase your chances of finding an option that makes you say, “This is awesome.”

However, my analytic side does play an important role in creativity. Novelist Sue Monk Kidd said in a workshop that writing comes about through a combination of “madness” and “measure.”

An ideal writing process honors both. In the “madness” stages of clustering and writing the rough draft, I allow thoughts to flow freely, no matter how silly or illogical. But the final product ultimately needs a internal logic, a cohesive design, a container for transferring the “madness” to others.

Structuring writing, identifying plot inconsistencies, revising for grammatical correctness, creating transitions between paragraphs, and analyzing rough drafts to identify problems are all about “measure.”

But how to you apply the more cerebral methods of problem solving to creativity without draining the life out of it?

I will sometimes “discover” my rough draft as I write. Images, dialogue, and character actions often surprise me. But sometimes when try to I force them to “make sense,” the playfulness is lost.

I have to make a conscious effort to let original, sometimes whimsical, imagery stay rather than replacing them by more sensible abstract terms that I am more certain people will understand.

At other times I will begin by writing with an outline, but my rough draft "wants" to go in a different direction. Sometimes I go with it and try to identify a purpose to my rough draft I might not have been aware of when writing it.

Instead of forcing order onto the rough draft, I let the rough draft “tell” me what its purpose is. I take note of recurring themes and any loose structural patterns. My initial purpose might be "how I tried to sneak a kitten home when I was eight." My new purpose could be: "why my parents hate cats." Once I discover my purpose, writing becomes a sort of puzzle that makes use of both logic and imagination.

I like puzzles, which means I sometimes enjoy the experience of being temporarily stumped. During those moments, I am relaxed and alert rather than frustrated, which is how I want to be when I write.

This mindset was useful when I was doing on-line freelance work. I was constantly being sent rambling drafts and manuscripts that were definitions of chaos. When I first looked at them, I would always think that turning them around would be impossible without starting over.

But as I read over them and made notes, I could usually see an underlying order to the text that the client may not have been aware of while writing. Themes and motifs appeared that suggested an overall purpose.

Once I identified it, revising became easier. I knew which passages needed to be cut and which needed to be strengthened.

In the same way, if my personal rough drafts begins to ramble I can always focus it by clarifying to myself what my purpose is such as to “tell what it is like to have bipolar disorder” or “explain how to tie a shoe.” Then I cut everything that does not support the purpose and strengthen the parts that do.

I try to allow for this kind of flexibility in my writing process. First I cluster and write a messy rough draft in my notebook. On the methodical end, I identify any hidden structure; clarify my purpose; type my rough draft and make changes as I go; revise; then polish.

The process works for me because it satisfies the needs for both madness and measure; for spontaneity and the need for structure and clear expression.

No matter how messy a rough draft is, it is an important step toward a cohesive product. As long as a rough draft is only in my head, there is nothing to critique, no practical questions to ask of it. But as soon as I write it down, that changes and I switch into question-asking puzzle mode.

If, for example, my writing seems too sentimental I ask, what is it that makes writing seem sentimental? Is it the overuse of abstract words such as “love”? It it trite expressions? Is it an overly dramatic sentence rhythm not matching the drama of the events described?

If I write these questions down, usually a solution follows. For example, I could tone down my sentence rhythm to match my less than dramatic event. Or I could make the event more traumatic to match the intense emotion suggested by the rhythm.

For the second situation, imagination is needed to invent my new scenario, so I would turn to clustering.

I like clustering because it feels purely free and imaginative to me. But in writing I have not found a way to keep my imagination and analytic side entirely separate. There is a constant dialogue going on between them. Sometimes my imagination does not become fully engaged until after I have typed my rough draft.

But being clear about what kind of problem I am trying to solve, technical or creative, brings clarity to the writing process so I am never at a loss for what to do.

My cerebral side creates structure. My inner artist says “I like this better than that.” Both are important.

Contrary to a common perception, art is not dumb. It is not easy. It is not accidental. Rather, it engages the entire personality, bringing cerebral and imaginative processes together.

Like any art, writing is a challenge, but it does not have to be frustrating. Writing is problem solving, which is the essence of skill, a relief from trial and error, and the path to mastery.

August 20, 2014

An Agnostic Voice from the Deep South

In my head I have no accent. I like to imagine I am self-created, aloof, and that I sprung from a vacuum. If my thoughts have an accent, they are more Queen Elizabeth than Honey Boo Boo. But my speech gives me away: I grew up in the Deep South.

I was born in South Carolina, where I lived for most of my life until I moved to Florida about a year ago, but I often find myself wanting to distance myself from my home state because while I was there, I changed.

That is, I discarded many of the conservative beliefs my family and most of the kids I grew up with still embrace. In a state that has been called the Buckle of the Bible Belt, I have been an agnostic since I was 15.

I also support gay marriage, find the death penalty barbaric, and think that Fox News is a parody of itself. The idea of “intelligent design” being taught in schools alongside evolution offends the rational empiricist in me.

I sometimes think my upbringing has shaped me mainly through my struggles to define myself against it.

During my childhood it was different. There was a sense of being enclosed and it was not all bad. At family holiday gatherings there was a feeling of closeness and good-humored warmth. Before the meal, family members gathered and held hands as someone led a prayer.

There was a sense of security concentrated inside the circle of linked hands, familiarity within, uncertainty without. After I jettisoned my religious beliefs, I felt cut off from that experience. I was secretly outside the circle, and no one knew.

In silence I was always disagreeing with those around me. In 1999 I moved to Atlanta, a city that was far more liberal. I saw the contrast culturally and intellectually to my conservative home town and I met people who saw the world in much the same way I did.

While there I felt adventurous and became a vegetarian. After a year of living in Atlanta, the Dot com bubble crash ravaged the job market and my husband and I moved back to my home town.

I was alarmed at how homogenized it was, how pale the faces were. It was a place where church was the dominant topic of conversation, and where people thought being a vegetarian meant you mainly ate chicken.

I stubbornly retained my new diet as long as I could.

Like vegetarians, atheists and agnostics in my home town were not so much reviled as unacknowledged. I have heard on the news stories about atheists getting fired for their skepticism or penalized in other ways, but I never saw that happen where I lived.

I never saw anyone abused for being an atheist because it was so rare for an atheist to admit to being one. Thus, everyone was free to believe whatever they wanted to about them.

For the most part, this belief was the one I was taught as a child: that atheists were near-mythical creatures who inhabited a dark and humorless realm of seething cruelty and unhappiness. The common assumption was that unless you had cruelty written all over your face, you must be a Christian.

After Atlanta, my home town had never seemed so constricting or so wrong-minded. On every block, it seemed, there was a church with a sign that said something like, “Hot enough for you? Hell is far hotter! Better start praying!” or “Heaven or hell: You choose!”

On every street the war of the bumper stickers raged on, declaring the evils of “Darwinism” or proclaiming “God, guns, country” or showing a “Jesus fish” eating a Darwin fish.

Seeing these kinds of proclamations everywhere made me want to to tell the people around me that things were not as simple as they assumed. A perfect storm of adolescent depression and religious confusion had prompted my induction into rational skepticism, and since then, everything I learned seemed to confirm that I was right to doubt my childhood beliefs.

But I did not think I was articulate enough to circumvent the years of indoctrination I remembered from my own childhood.

My suspicion appeared true; trying to explain my position to my parents always ended in terrible frustration. Though I loved them, I often felt infringed upon, silenced, and repressed by repeated attempts to bring me back “into the fold.”

A little over a year ago a financial crisis culminated in my move to Florida. Living here has lifted some of the pressure to conform. While Florida is geographically south of my home state, it is not “the Deep South” culturally.

Though politically conservative, Florida does not assume prescribed beliefs or affiliations. Ocala, where I now live is more ethnically and culturally diverse than the town I left. There are not just Christians here; there are Scientologists, Jews, agnostics, atheists, and Mormons. It is simply impractical to assume everyone has the same lifestyle or believes the same things.

Thus, I have felt more comfortable about discussing my agnosticism in my blog than I was before I moved here.

Moving has offered other advantages. Like viewing the earth from the moon, being away from my home town has granted some perspective. From a safe distance, I can remember what I enjoyed about living there as well as what I did not.

I remember small things, like how much I loved the macaroni and cheese and sweet tea that my grandmother made, and how she was quick to refill the glasses even if I had only taken one sip.

For a long while I could not seem to find any place that served authentically southern macaroni. I missed it, a sort of casserole of noodles, butter and cheese with a crust baked brown on top.

While I have rejected southern conservatism, I am more aware of being from South Carolina than I was when I lived there. I know that my craving for sweet tea is not universal. And it is relatively rare to hear true southern accents where I live, so I am far more aware of my own.

At times I want to disown it. I am horrified at some of the things South Carolina does politically.

At the same time, I resent stereotypes that it is a state full of Honey Boo Boos, drawling politicians, and uneducated buffoons. Like my dad, who was a college professor, there is a robust educated population whose members are rarely represented in television and movies. Moreover, there are many liberals in South Carolina in towns like Columbia and Charleston, although they are exceedingly rare in my home town.

Whether I like it or not, being away from Deep South culture has made me feel like more of a southerner, and I am sometimes astonished that my background affects me as much as it does.

But maybe I should not be. A place known for intolerance of minorities is also the place where I took my first steps, tasted ice cream for the first time, got my first crush, and read my first book. It is where most of my family still live, and despite differences of religious and political opinions, I miss them.

By moving to Florida I have left my past behind but, like a sad, abandoned puppy, it has followed me here. It should be no surprise. It was by reacting to and reacting against my home town that I have become who I am. As a result, there will always be the tell-tell sign of my accent, a vocal wavering, a trace of history that resonates through centuries.

From the chorus of my own accent and the unfamiliar accents all around me, I see how much a geographic location can shape the minds and habits of those who live there. But in order to fully understand how much, I had to leave my home state.

I did, and from only two state borders away, I have discovered something I once dreamed about: the freedom to exist as I really am, and not as I am expected to be.

August 13, 2014

Should Word Count Limits Have Limits?

This is a strange idea to me, since a longer story means that I put in extra work. But while querying for an agent, I have found that most publishers will not even consider a novel over 100,000 words. Mine exceeds that limit substantially.

I should not be surprised. Word limits have always been basic to publishing, whether they are for a novel, newspaper article, or short story.

If there is any conflict between word limits in publishing and the art of writing, I have never seen it mentioned. That is probably because cutting verbiage can do miraculous things for the quality of a story. Beginning writers often pad their stories with words that do nothing to drive a story forward, and trimming excess text can reveal the treasure inside.

Thus, a “shorter is better” ethic has emerged among many writers. Perhaps this accounts for the recent popularity of super-short stories.

NPR has a contest called “three minute fiction” and the media hub Reddit now has a section called “One sentence stories.” Perhaps one-word stories will be next: “ran” or “swam,” as the pinnacle of literary minimalism.

Supposedly these super-short stories propel normally verbose writers to divine heights of succinctness. But has it gone too far? Are there limits to how much you can limit a story without it losing its essence?

The “shorter is better” trend is being taken to such extremes that I wonder: If shorter is better, would a nonexistent story be the best story of all?

I think not. Even minimalist stories suggest that people see value in the short story form. Short or long, stories seem to be deeply ingrained into the human psyche. Ideally they enrich life and further understanding of the world.

But, despite my misgivings about stories being reduced to sentences, I must admit that brevity has benefits.

I recently began a project to write a short story every weekend. A refreshing change from writing novels, short stories allow me to test a wide range of ideas without a long term commitment. Ray Bradbury was my inspiration for the project.

He built his skills by writing a short story every week and advised any aspiring writer to do the same. As he suggested, writing a lot of short stories prevents me from getting too bogged down in a single project. Given the minimal risk and time commitment, no idea is too silly to try.

But I ran into a problem. Embracing the “shorter is better” ideal, I tried to limit my stories to three pages on my computer. But when I did that, I was unable to complete them. Even after I jettisoned large chunks of text, my stories still wanted to be at least 5 pages to “feel” complete. Stories are not just pages. They are patterns with rising action and a conclusion. To make a full artistic statement, I seemed to need more space.

Finishing my stories is important to me. Most of the stories I wrote during high school and college were incomplete. I would present an enticing hook and a compelling conflict, only to run out of creative energy mid-way and discard the project.

I have written a lot more since college. Some pieces are better than others, but I always go out of my way to finish my stories. I may not have the perfect ending, but, good or bad, I always create one. The habit of completing my stories and articles marked a turning point in my writing skills.

For my current story project I raised my limit to five pages. Still, I rarely had room for more than one scene. I thought I needed models to show me how to write super-short stories well. The ones I remembered best were childhood stories, fairy tales and fables, so I downloaded a book of stories by Aesop.

In terms of character development, there was no much there. The characters of Aesop were animals, each with one defining trait: the hungry wolf, the slow but ambitious turtle, or the wounded lion.

As a kid I loved this kind of story. But around age 12, I discovered that stories could be used to create a point of view and a sense that I was reading the minds of characters. Afterward I never wanted to read another fairy tale or fable. They seemed unsatisfying compared to fiction that could simulate consciousness.

But there is more to stories than thought flow. I wondered if my inability to bring my short stories to a close within a 3 page limit was a skill issue. After all, a short story is a different form with different needs than those of a novel.

For inspiration I turned to the acclaimed master of the short story, Anton Chekov. I downloaded an anthology of his stories on my Kindle, thinking that a master of succinctness must have numerous super-short stories to his credit.

But I found that his stories were not that short, or at least not internet-short-attention-span short. Though insightful, they would not have qualified for the NPR contest.

Even in my college literary anthologies most of the short stories were 5 pages or longer. Though the masters were succinct, they were clearly not slaves to a “shorter is better” ethic. This made me wonder: When you shorten a short story to a nub, what do you lose?

A lot. The longer short stories in my anthologies were far more satisfying to me than the fables of Aesop. The shorter a story is, the more it loses nuances of character, plot progression, sensory details, and figures of speech, which make a story enjoyable. I wondered what Huckleberry Finn would have been if Mark Twain had reduced it to 100 pages. Maybe it would have been fine, but it would not have been the same story.

For me, word count limits need limits. That is, a story should be as long as it needs to be to accomplish its artistic purpose.

Along with point of view, story length is another factor that affects the design of the finished product. Shorter is not always better. Sometimes cutting writing to its most basic components makes it shine. At other times forced brevity drains it of life and meaning.

Practical considerations such as limited magazine space sometimes interfere with what is artistically ideal. But a long story does not have to be a verbose story. A skilled writer can claim more space, yet still make excellent use of it.

An interesting story that is long but conservative in its word usage deserves a warm reception. If it is banished for exceeding an arbitrary word limit, it needs to visit a friendlier household whose members like to read.

August 6, 2014

Short Story: Rational Therapy, Inc.

But while reading the fascinating books Bivalent Logic and Aamrgan by Cliff Hays, I reconsidered. I wondered: If I could change my feelings with logic, how could it work? This story is in honor of the possibility that it could.

26 year old Katy stared at the “Pythagorean playground” with mistrust, a yard full of soaring geometrical structures leading to cube of a clinic. This was not like any psychiatric office she had ever seen. But then, that was the whole point.

Normal psychiatrists had failed her, had given her sedatives and asked her questions, which were pointless since she had already answered those questions to herself many times.

She needed therapy that could tell her things she did not already know. She had been told that this was the place for that. Here, she was told, therapy depended on learning. What she would be learning, she did not know.

The Rational Therapy Institute was secretive and reputed to be “experimental.” Patients could only enroll by invitation, though visitors, attracted by the unusual park, could explore the exterior grounds and take photographs.

The secrecy, some conjectured, was a publicity stunt. The patients who had received treatment from the institute had been forced to sign a contract promising not to divulge the type of treatment they had received.

The media had a field day. The institute stopped cars with its towering geometrical structures, its pyramids and orbs of blue and red marble. Katy followed the stone path to the the rectangular door, went up a short set of stairs, latched onto a circular door knocker, and banged.

A tall man opened the door, his hair steel-gray, sideburns framing his face severely next to an unsmiling face. “Ah. I see that you came,” his voice was deep and flat, but his eyes were alert and appraising.

She had expected “hello” or “how are you doing?” and had been prepared to answer accordingly. But what was the answer to the non-question, “you came,” a simple and obvious observation? She opened her mouth but nothing would come out.

She stepped inside, expecting soft lighting and antique furniture to match the door knocker. Instead she found an almost empty foyer with severe white walls and white marble floors. The only furnishing was a small wooden table next to the door stacked with papers. A mirror graced the wall across from her. The lighting above it was harsh and revealed her every flaw. She turned away.

“If you will come with me,” the man said. The flatness of his tone unnerved Katy. The office at her previous psychiatrist had been lushly furnished with puffy carpeting, soft lighting from lamps, and bucolic landscape paintings.

But here, nothing had been done to comfort patients. No flowers adorned the foyer, no magazines were displayed on a coffee table, and her host reminded her of Dracula, except not as charming. Still, Katy could do nothing else but follow.

Her sandals thumped self-consciously against the hard surface of the marble floor. The marble tiles made Katy anxious because tiles had lines and Katy did not like lines on floors. She tried to never to step on any of them. She could not explain why. But then, that was part of why she was here.

She expected to be taken to a waiting room, doctors always had waiting rooms, but instead she was ushered directly into a spare office with straight hard-back chairs, a desk, and sedate bookshelves made of plain, unfinished wood next to a whiteboard. The nameplate on the desk said “Maxmillion Elmsworth, Logical Practitioner.”

There was a rustling sound from an adjoining room. She tried peaking to see who it was, but before she could, a man emerged, wearing the same kind of suit men wore at funerals. He was younger than her original host. His hair was darker, a shoe polish black. “Oh good,” he said. “You came.”

The same mild surprise, the same unwelcoming greeting. This was like no medical facility she had ever visited. Where was the friendly “customer service” she had been taught to expect? She wondered if there was a manager she could complain to.

As if reading her thoughts, the man forced his lips to smile, though she could see little warmth in his eyes.

“Um, hi,” she said. “Good to meet you.” She held out her hand. The doctor only stared at it in mild amusement until, suddenly self-conscious, she settled into one of the hard wooden chairs.

Standing above her, he peered at her through a set of wire-rimmed spectacles. “So tell me,” he said. “What brings you here to Rational Therapy, Inc.?”

She stared at him. Though Katy remained wary, the question had put her on more comfortable, familiar ground. The truth was hard to say, but Katy made herself say it. “I am neurotic and afraid of life,” she said. “I am afraid of cars, water, and lines on the floor. Ever since my divorce, I have been afraid to get up in the mornings, afraid to do anything.

“I have abandonment issues from when I was little and my father left my mom, and my own divorce brought all the bad feelings back. Since then, I have destroyed all of my relationships. My friends said I was too needy and started avoiding me. And when I step outside myself and see what I am doing, I can see how awful I am acting, but I am unable to talk myself out of it.”

“I see,” the man said, “Perhaps I can help you.”

“Please,” Katy sighed. “I have tried everything, the anti-depressants and tranquilizers, the talk therapy, the group therapy, the self-therapy. I even read Freud, who is supposed to be the expert on this kind of thing.” She unsnapped her purse. Hoping to impress, she withdrew a dog-eared copy of The Psychopathology of Everyday Life and showed it to the doctor.

When she held the paperback out for inspection, the doctor stared at the book. Then he took it by one corner and dangled it as if holding a dirty sock. Sensing reproach, she reached for the book, but he made no move to return it. Instead he opened the book and tore out the first page, then another.

"Hey, what are you doing?” she said. “I paid money for that.”

"Treating it as the rubbish it is.” He walked over to the paper shredder on his desk and fed the page into a slot. The machine whirred on reception and clacked. It was the loudest paper shredder Katy had ever heard.

Katy had stood without realizing it and stared at the “doctor” in frozen horror. “What the hell?”

With relish, the doctor tore out a new page and fed it into the slot, which clacked some more.

"You just ruined my book. You…you owe me another.”

"I assure you," the doctor said. "I am doing you the biggest favor of your life.”

"Oh yeah? How do you figure that?"

He tossed the rest of the book into a wire waste basket next to his desk. Then he sighed, pulled a chair from behind his desk, and moved it forward to face Katy.

He sat down and studied her. “Despite its claims, the history of psychiatry has been mostly the history of human denial.

“Our society has done a terrible job of treating mental illness: the talk therapies that encourage emotional excess; the pills to alter unpleasant moods; the self-help books that promise easy answers. One day people will look back on all of it and think of our current methods the way we now think of bloodletting to cure disease.

“The goal of modern psychiatry is, itself, misguided. It seeks to create well-functioning and efficient citizens who can hold a job, raise their kids, and fuel the economy until they die. Our goal is different: to help you discover what is true. Psychiatry purports to do just that, but it has been lacking an essential tool.

“The answer to mental illness has been staring us in the face all along, but most of us have been unable – or unwilling – to see it because learning it takes effort and dedication.”

“Well? Go ahead, tell me,” Katy said. “What is the answer? What do I need to learn?” She leaned forward, propped her elbows on her knees, and stared beseechingly at him. “I will try anything.”

The doctor stood, moved toward a bookshelf, and selected a hardback before returning to Katy and handed the book to her. She took it and scanned the title: Principia Mathematica. “Math?” She shook her head. “Why are you giving me this?”

“I am answering your question. What is the real answer to mental illness? Considering that mental illness has its basis in reality distortion, the cure, the aim, and the prescription for mental illness must be the truth. And what truth is more timeless, more reliable than mathematics?”

Katy stared at him, expecting further explanation or some hint that he was teasing her. “Math? You are proposing to cure me of my phobias and insecurities with math?” Katy studied the doctor, but he still did not smile.

“Indeed.” He continued to look seriously at her. “And not just any kind of math, but the kind that requires the faculty of logic.”

She waited for him to say more, but he was silent, waiting for her response. “Please tell me you are kidding.” She began to look frantically around the room. “I failed ninth grade algebra.” She stood. “Math hates me, I avoid it whenever I can. Oh my God.”

Her host regarded her calmly.

She felt claustrophobic suddenly. She stared at the door, thinking that if she did not leave at once, the walls would come together and crush her. “Oh my God, this a nightmare, I thought you had real answers. I need fresh air. I feel dizzy.” She took a few steps and braced herself against the wall nearest to the door, her breaths coming quick, her heart thumping. “What is happening to me?”

The doctor stood and stared at her calmly. “It is commonly referred to as the fight or flight syndrome, activated by the autonomic nervous system during times of inordinate stress. Math induces that reaction in some. But I assure you: the feeling is quite normal and will pass.”

“Like I said,” she said between gasps, “math hates me, it will never cure me, you must be insane.”

“I suspect that your attitude is largely the source of your problem. Had you not succumbed to mathematical indolence, perhaps you would have had a better life and would not need to be here.”

She glared at him. “Look, I did not come here to be insulted. And who uses math as therapy?” She stared accusingly at the doctor. “No wonder you people are so secretive. If anyone knew what you really offered here, they would stay the hell away from you. No one has said hi to me since I got here. You are the unfriendliest doctor I have ever met and your office…,” she sniffed, “smells funny. What is that, licorice?”

"I was only speaking out of concern for you, because if you are as disinclined to math as you say, remediation may be necessary as a first step to your emotional recovery,” he said. “Without an adequate foundation, you will be unable to comprehend the essential course work.”

"Course work? You want me to take courses in math? What is this, a zoo? I already graduated from college, mister. That part of my life is over, thank God. No deal. You are crazier than I am. I am going home.”

“Very well.” The man stared placidly at her. “But if you leave here, where will you go? What kind of life will you be returning to? Will you return to your phobic, friendless, loveless life so easily? Are you going to give up so quickly, without at least listening to what I have to say?”

She took a long deep breath. Her shoulders felt heavy and limp. She had to admit, he had a point. She moved back to her hard chair and almost stepped on a line but caught herself in time. She settled back into her chair.

The doctor stood and strolled once more toward the bookshelf against the wall near the door. He ran a long pale finger along the bindings and pulled a new book from a shelf. “For the duration of your treatment here, you will be required to keep a journal.”

“I already keep a journal,” she said. “I have since high school.”

“This journal will be different from any kind you have ever kept, a journal of logical statements. Have you ever heard of the fallacy called affirming the consequent?”

“No,” she said.

“Well, I will get to that in a moment.” He stepped over to her and offered her a thin book with a glossy cover. “Normally I like to start my patients off with Principia Mathematica as a primer. But given your mathematical disinclination, perhaps you would prefer this one, Fun with Numbers.”

She glared at him. “I know basic arithmetic.”

He exhaled. “Oh, excellent.” He set the book his desk, “that should make our task easier. However, what I am about to show you requires no math but only the ability to comprehend logic. It is an excellent starting place for showing you what we do here. You said your problem was that you are needy and afraid of life. These fears of yours can be written in the form of statements.”

"Statements? What kind of statements?”

“Formal assertions.” He stood, went over to the whiteboard, and erased some scrawled formulas that were already on it. “Can you give me a specific example of a time when you drove away people whom you loved? Suspected you were behaving irrationally, but were unable to stop yourself?”

She tensed. "No, not at the moment.”

“Well, tell me about one of you failed relationships.” He studied her. “When did it end and how?”

Resisting the impulse to bolt, she thought about the mess her life had become and forced herself to stay put. “My husband, he cheated on me.” She struggled to keep her voice steady and failed. “Denied everything, but I knew.”

“You knew. So tell me. There must have been clues. Was there any anything in particular you noticed? The smell of perfume on his clothes? Strange phone calls?”

“No, nothing like that. But he lied."

“He lied. Please. Elaborate.”

“Well, when I first met him, he was already engaged to another girl. He told her he had been other places when he was really with me. After a while he broke up with her.

“Months later, I married him. He worked late sometimes. One day he told me he would be spending the night at his office. That night I missed him, so I went there to visit him. The office was locked, but I had a key. The building was dark, there was no one there. I was afraid he might have gotten into an accident on the way.

“But the following morning he came home as usual. He looked and acted fine. I asked him if he had spent the night at the office like he planned. He said he had. He lied to me, and I knew. Knew he was cheating on me.”

“Ah,” he put his fingertips together. “You were afraid. Afraid because you suspected the same thing could happen to you that happened to his ex. The lying. The silence. The unpleasant reality. The devastating revelation.”

“Well yes.”

He nodded. “Your fear can be viewed as a kind of emotional prediction then. A belief. A premise. To you, an axiom. Therefore, we can write it as part of a conditional statement: If my husband ever cheats, then he will lie about where he has been. Though this is a highly questionable assumption, let us assume, for now, that it is true and write it out as a formula.”

The doctor picked up a marker and on the board wrote:

1. If P, then Q.2. Q.3. Therefore, P.

He looked at her.

“Well go ahead,” Katy sighed. “What does it mean? I have a feeling you’re not going to let me out of here until I know.”

“Affirming the consequent is a fallacy which says that given a conditional along with its consequent, we are able to deduce its antecedent.”

“Please,” Katy said. “Can you talk like a human?”

The man sighed. "Maybe I should start with an example. Take this one: If an object is a star, then it must be hot. A candle flame is hot. Therefore, a candle flame must be a star.” He looked pointedly at Katy. “Do you see anything wrong with this reasoning?”

“Other than it not being true? I agree, it makes no sense." She sighed. "No more than anything today has made any sense.”

“Good. Then we agree thus far. Let P – as the antecedent – represent the first part of our statement: ‘If an object is a star.’ The next part of the sentence, Q, is the consequent: ‘then it must be hot.’ But if you reverse the two parts of the statement and say, ‘If an object is hot, then it must be a star,’ it is obviously untrue. Agreed?”

Katy nodded.

“The inability to make a valid deduction by reversing the two parts of a conditional statement is called converse nonequivalence. But people use this false reasoning all the time to try to prove things that are less obviously false.”

“Let us apply the principle to your situation. The reverse of the your original statement is, ‘If my boyfriend lies to me, then he is cheating.’ Do you see? You have used faulty reasoning to reach your conclusion. A fallacy.

“To put it simply, there could be many reasons your husband lied to you. Perhaps he was going to A.A. meetings in secret. Perhaps he wanted time alone. Maybe he was planning a surprise birthday party. Given the complexity of human behavior, many scenarios are possible.”

At first she only stared at him. She looked at the letters on the board and they began to blur.

At the same time, something inside her shifted, alarming, almost electrical. She felt the way she sometimes did when a roller-coaster crested the rise and dropped her into space.“The day I broke up with him, it was my birthday. He seemed happy and excited that day, before I made him leave. Before I yelled at him.

“I remember so clearly how he changed, how his face looked, first hurt, then anger. What if he was planning a surprise birthday party? I never let him explain. I screamed at him. When he tried to talk I just spoke louder to drown him out. I remember the hurt on his face when I pushed him out the door, told him to never come back, said I never wanted to speak to him again. Oh my God, what if I drove him away for no reason?”

"Perhaps, perhaps not. But clearly your unfounded assumptions have been affecting your decisions, indeed your entire life.”

Those words “your entire life” settled into her mind and would not leave. Every self-doubt she had ever had seemed to pull together and condense inside them.

“Oh my God,” she said. “I have been affirming the consequent all my life and I never knew. What if the biggest decisions of my life have been made based on – what did you call it – a fallacy? What I think and do because of it are what make me who I am. Who am I? Most of my memories, my interpretations…”

“Are probably false.” He paused. “My apologies. You seem distressed. Would you like some licorice?”

Katy raised her head and stared at thin black rope the doctor dangled in front of her nose. “You think licorice is going to help me? My whole life might be based on a lie, I am falling apart, and you offer me licorice?”

"No pressure. I will be more than happy to eat it myself.”

“Oh God.” She snatched the string of licorice from his hand. “I should never have come here. Before I came, I knew. I knew he was cheating, it was so obvious, the divorce, it was such a nightmare. But I felt good about breaking up with him. What if I was wrong?”

“Congratulations, my friend. You have made significant breakthroughs on your first visit, despite your aversion to my formulas, which you must overcome if you wish to progress. You must begin to keep a journal of logical statements. Whenever you make an assumption based on your feelings, I want you to write them down as conditional statements. If one of them contains a fallacy, you will become aware of the illogic that has been governing your life.

“You must also examine your assumptions, such as ‘If my husband cheats, he will lie.’ Given the complexity of human behavior, it is impossible to make those kinds of predictions with reliable accuracy. But writing your thoughts in the form of conditional statements will expose flaws in your thinking and bring you closer to the truth.”

She sniffed. “I always thought I was intuitive.”

“For many people, the word intuition is only a way of saying that their emotions grant them special knowledge. But feelings tell you little or nothing about the outside world. Logic is a powerful tool for breaking through confusion.”

Katy raised her head. “So, what, are you saying that mathematicians are the sanest people on earth? I have met some crazy people who are good at math.”

“Mathematicians too seldom apply what they know to their emotions. For too long there has been a dichotomy. Feelings and logic are viewed as mutually exclusive. But emotions can be brought into adherence with logic. You said that you cannot talk yourself out of irrational feelings.

“Emotions and logic do argue quite frequently, but your emotions are winning all the arguments. If you want to think and act reasonably, then your logical voice must become better at arguing. The disciplined study of logic expressed in the language of mathematics will strengthen that side of you. But I am warning you: your emotional recovery will not be easily won. You must study. You must calculate. You must commit.”

Katy stared at the book the doctor had given her, Principia Mathematica.

"Mental illness," he went on, “is only a form of the irrationality to which all humans are prone. Many people deemed sane by society delude themselves in order to go about the daily practice of living. But to look reality in the eyes, full on, and still embrace life, is a rare ability. So is embracing uncertainty, when uncertainty is all there is. The goal of this therapy is not to restore you to productive denial, but to open your eyes. The only cure for mental illness worth pursuing is the truth.

“I am going to encourage you to question your own thoughts and what others have told you. By the end of your training, you must question me as well. When you have tested your most basic assumptions, subjected them to the uncompromising light of logic and even been brutal to them, you will look at what remains and may catch a glimpse of the truth, which is hard won, but the greatest treasure there is. And when that happens, you will change, and your life will change too.”

Katy sat still for a long moment. During the speech, she had been clutching the book Principia Mathematica to her chest. Now she lowered it to her lap, sighed, and shook her head. “Okay,” she shrugged, “What choice do I have?”

The doctor grabbed a prescription pad from the desk, withdrew a pen from his shirt pocket, and began to scrawl. “You will need to purchase a scientific calculator, a book of annotated writings by Aristotle, and a book of graphing paper.”

“Graphing paper?” Katy looked at him. “Why on earth would I need graphing paper for a mental illness?”

He stared at her with eyes full of unblinking candor.

“Okay.” The word was almost a whisper. “But this is running up a bill.”

“If the 2.99 cost of graphing paper presents an insurmountable challenge for you, I heard the office supply store down the road is having an excellent sale.” He withdrew a sheet of paper from his desk. “Coupon?”

Katy stared at the coupon for a long moment. Then she sighed and took it. Was her whole life really just a fiction she had told to herself? She had nothing to say and felt heavy, like she could barely contain her own weight.

The doctor ripped out the prescription and handed it to her. “Next week, same time?” he asked.

Katy thought about her life at home, all the insanity, the moods, the uncertainty, the fear, a life forged from bad decisions. Beside all that, a little math did not seem so bad. “Yeah, okay.” She rose and took the prescription. “Next week.”

"Very well. You can pick up the schedule for the course work at the table next to the front door.”

On her way out the elderly man who had opened the door was sweeping the floor in the foyer. When he saw her, he lifted his head in mild surprise. “Ah, I see that you are leaving.”

She picked up one of the schedule sheets from the square table beside the door. “Ever heard of the words hello or goodbye?” she said. “Some people find them useful.”

The man stared silently at her.