Austin Ratner's Blog, page 3

March 13, 2013

In the Land of the Living

I will be blogging this week about my new novel In the Land of the Living, just released by Little Brown. Here is an excerpt of the first blog, which appears on the website of the Jewish Book Council:

Remember Mandy Patinkin’s character Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride? When Montoya was a child, the story goes, the six-fingered man killed his father. He also slashed Montoya’s face, leaving him with scars on both cheeks. Montoya spends the rest of his life training to exact vengeance on his father’s killer. He practices not only his swordsmanship but just what he’ll say when he finally finds and confronts the six-fingered man: “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

The main character in my second novel In the Land of the Living is a boy like that, a boy with a dead father, a boy bent on recompense and committed to its pursuit for as long as it takes. His problem is that there is no six-fingered man to kill....

To read the rest, follow this

link.

Published on March 13, 2013 08:36

March 8, 2013

Russian Winters

Snowdrops: A Novel by A.D. Miller

Snowdrops: A Novel by A.D. MillerA.D. Miller's Snowdrops is a novel about Moscow, today's Moscow, the one where somebody pays off gangsters to throw sulfuric acid in the eyes of the director of the Bolshoi. But in Snowdrops systemic graft has so compromised the criminal justice system that it barely appears at all in the midst of the anarchy. In this beautifully written English novel, which was a Booker prize finalist, every person and every institution made of people is corrupt. Anarchy permeates all just like the cold of a Moscow winter. And it's a novel that's as implacably real and engulfing to the senses as a long, freezing Muscovite winter.

Surely Russia has not always been so corrupt, but it probably has always been so cold and so vast. In this sense Miller, who is also a journalist, writes in a timeless and literary way. He shares in the secret wisdom of the novelists, playwrights, and poets who have been Russia's biographers, a wisdom born of intimacy with the mighty indifference of nature, history, and humanity itself to the designs of the human individual. No wonder atheism is one of Russia's major exports.

Says the character Ananyev in Chekhov's story "Lights":

And concentrating the whole world in myself in this way, I thought no more of cabs, of the town, and of Kisotchka, and abandoned myself to the sensation I was so fond of: that is, the sensation of fearful isolation when you feel that in the whole universe, dark and formless, you alone exist. It is a proud, demoniac sensation, only possible to Russians whose thoughts and sensations are as large, boundless, and gloomy as their plains, their forests, and their snow.

A.D. Miller writes about expatriates, yes, in addition to Russian natives, but his narrative is in so many ways pure Russian. Were he to set foot in A.D. Miller's Moscow, Chekhov would know where he was immediately: lost. Lost as you can only be in Russia.

View all my reviews

Published on March 08, 2013 12:12

February 9, 2013

Tree Hugging

The Life of the Skies: Birding at the End of Nature by Jonathan Rosen

The Life of the Skies: Birding at the End of Nature by Jonathan RosenRabbinic tales about the famously wise King Solomon tell of his special ability to talk to animals and to apprehend the subtleties of nature. As such, the Solomon legends hold particular interest for Jonathan Rosen, who himself writes of birds and nature--and of those who write about birds and nature--with a rather Solomonic subtlety.

"Darwin did more than anyone since the serpent in Genesis to disturb the feeling that we were safe in a world of sacred guarantees," Rosen writes (p. 176). But Rosen is less interested in Darwin's ramifications for theology and more interested in how naturalists and poets after Darwin have rediscovered a kind of spirituality, if not religion, in nature itself. He reports on a shift of weltanschauung that Thoreau biographer Robert Richardson called "the shift from the old religion of God to the new religion of nature." (p. 247) The Big Bang inspires a certain religiosity, for example, that Rosen articulates perfectly: "With science like that, who needs mysticism?" (p. 173) According to Rosen, Emily Dickinson's poem that begins "A Bird came down the Walk" belongs to this shift too: "birdsong has taken the place of church music in this poem." (p. 193)

For American poets, who are naturalists maybe by way of America's wide open spaces, birds seem to play a special role as emissaries of the mystic majesty of nature. They sing a harmonic line throughout the poems of Whitman, Dickinson, Frost, and Stevens and Rosen is a consummate analyst of such birdsong. Their power of flight and song, and their gratuitous beauty of coloration, must partly explain their fascination for poets. But in an urban environment, Rosen suggests, the birds are also the last representatives of the wild. (They are at least the loveliest if not the last--with all due respect to rats and roaches.) They're "the only animals that make house calls." (p. 193)

The dark side of the new post-pagan, post-Christian nature religion is that it can still partake of the ascetic fervor of religions of old. Henry David Thoreau is a good example. Rosen writes that "Thoreau attempted to marry nature the way nuns marry God." (p. 149) One could even say that the passion for virgin forest is sometimes a plea for literal virginity itself. "I think that I shall never see / A poem lovely as a tree," Joyce Kilmer wrote just before volunteering himself as cannon fodder in the first World War. "Poems are made by fools like me, / But only God can make a tree," the poem concludes. Maybe so. But that sapling poem has outlived a good number of forests.

The neglect of nature is unaesthetic, uncultured, and unfeeling to the living things that share our home planet, whether man, mouse, or mycorrhiza. But an excess of chastity about the human footprint in nature is, as Rosen rightly argues, a form of martyring despair and a flight from love.

Rosen states succinctly: "The great question facing us today is, Can we be both [environmentalist and humanist]?" (p. 248) "Extremism--of religion or materialism--of pure environmentalism or pure urbanism--is not the way." (p. 251)

Published on February 09, 2013 18:51

December 26, 2012

Peloothered

Intoxerated by Paul Dickson

Intoxerated by Paul DicksonAh, the holidays. The end of the year. When you celebrate by a cozy fire with the shiver of time in your fillings. When you cozy up to those you love best and those who therefore make you crazy. In other words, time to drink.

Melville House Books's "Definitive Drinker's Dictionary," Intoxerated, a fun compendium of annotated synonyms for the word drunk, provides the literary drinker with a smidgeon of words to go with his smahan of whiskey. (Smeahán being Irish, according to the OED, for a drop of whiskey; see James Joyce's wonderfully woeful drinking story, "Counterparts.")

Herman Melville himself, however, took a somewhat dryer approach when he launched American literature "on the high seas" (one of many sailing metaphors for drunk according to Paul Dickson's book). Having adopted some of the abstemious spirit of old Nantucket, perhaps, Melville introduces alcohol in chapter 3 of Moby Dick with a barkeep named Jonah who "dearly sells the sailors delirium and death. Abominable are the tumblers into which he pours his poison." One sailor there in the Spouter Inn abstains from drink, and when the sailor (named Bulkington) reappears in chapter 23, "The Lee Shore," it's as the type who eschews the false comforts of shore for the raw, cold, hard truths of the ocean. Under the terms of the allegory that spans chapters 3 and 23 of Moby Dick, alcohol counts among the false comforts.

Certainly, alcohol blunts reality, not least the reality of one's own self; isn't that why people need it? The many euphemisms for drunkenness are a further evasion. But as much as drinking is an honorable literary pastime, the many euphemisms for it appear relatively uncommon in literary works, perhaps because such works deal in undiluted truths, and in novels and stories alcohol is either the antidote to realities too acutely perceived or the disinhibiting solvent that liberates a character from his blinding fear.

Ernest Hemingway's hard-drinking characters in The Sun Also Rises seem to chase from bar to bar partly in flight and partly in search of liberation from self-deceptions much deeper than mere intoxication. Drinking in that novel is like a portal through which a tortured soul might claw back some semblance of pleasure, aggression, instinct, sincerity. Perhaps as a consequence, Hemingway relies mainly on the self-sufficient term "drunk," which is like onomatopoeia for the sound of the soul denting its rear fender on the telephone pole of life. There's one exception in the dialogue toward the beginning of part II: when Jake judges Bill much drunker than he is and calls him "pie-eyed" (p. 78).

Euphemisms for drunkenness are equally scarce in Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. A multi-faceted Shame has driven the mental patients in that book into the unhealthy safety of Nurse Ratched's psych ward, and alcohol enters as a sort of holy reprieve from Shame. Drunkenness sets up a cataclysmic change in Chief Bromden that ultimately emancipates him from fear:

As I walked after them it came to me as a kind of sudden surprise that I was drunk, actually drunk, glowing and grinning and staggering drunk for the first time since the Army, drunk along with half a dozen other guys and a couple of girls--right on the Big Nurse's ward! p. 260.

Daisy Buchanan appears “drunk as a monkey” on p. 70 of The Great Gatsby, and the phrase is duly noted in Dickson’s Intoxerated, but otherwise F. Scott Fitzgerald too treats inebriation with a certain sobriety. Alcohol flows through his novel’s pages as through a human bloodstream. It’s the medium through which the characters think, a disorienting twilight between dream and reality. Of note, neither Daisy nor Gatsby are heavy drinkers (see pp. 71 and 91). They are not content to live in dreamy drunken twilight, but strive to escape into a hypothetical place where dreams turn solid and come true.

In Joyce’s story “Counterparts” and in others in Dubliners, alcohol seems to purify the element of self-destruction in characters, but the penultimate story, “Grace,” celebrates a bit of drinking, even to excess. In a spirit of self-sympathy rather than self-destruction, Joyce makes use of one of those funny synonyms for drunk: Mr Cunningham calls Tom Kernan "peloothered" (Dubliners Viking Critical Library edition, p. 160; Dickson may want to add this one, as he has "plootered" but not "peloothered" on p. 134!). Kernan was so peloothered that he fell down the steps to the lavatory and bit the end of his tongue off. The funny euphemism seems to handle Mr Kernan’s indignity with a certain care and gentleness—perhaps because Kernan and his friends have already made their peace with instinct. "Glasses were rinsed and five small measures of whisky were poured out,” Joyce writes on p. 167. “The new influence enlivened the conversation." And on p. 169 comes one of my favorite lines on drinking: "The light music of whisky falling into glasses made an agreeable interlude." “Grace” is a wonderful story about moderation, and it very consciously applies the principle of moderation to moderation itself. In other words, to be perfectly moderate, and not too abstemious, you must also be immoderate now and again.

When I arrived in Connecticut for Christmas, my brother-in-law had a nice bottle of sipping tequila, a Centenario añejo, waiting for me. It stood me in good stead through four and a half hours of assembly of a “wired control robotic arm kit” for my older son, and through other minor holiday travails. So let’s raise a glass and face the New Year ah-wat-si (“crazy-brave,” according to the Blackfeet Indians, Dickson p. 16), if not completely jugged, lock-legged, and shot in the mouth. :*)

Published on December 26, 2012 07:15

December 12, 2012

Doublethink, Consciencethink

1984 by George Orwell

1984 by George OrwellGeorge Orwell's famous dystopian novel 1984 could be the best prose ever written in the science fiction genre. Its anti-fascist themes remain relevant too. This description of an overzealous patriot beset by "war hysteria" may sound familiar to anyone who's watched Bill O'Reilly on Fox News: "a credulous and ignorant fanatic whose prevailing moods are fear, hatred, adulation, and orgiastic triumph." (1984, p. 192) Yet the novel's purview is bigger than just politics, and its outlook might be summed up like this: what is righteous is not necessarily right. Or, as the emancipated Roman slave-turned-playwright Terence wrote two millennia ago, "The strictest justice is sometimes the greatest injustice." An immoderate conscience is like a totalitarian conspiracy against the self, and Orwell's totalitarians are conspicuously interested in their subjects' inner lives after the manner of conscience. When Big Brother, the face of 1984's totalitarian regime, stares at protagonist Winston Smith from the cover of a doctored history text, Orwell writes:

It was as though some huge force were pressing down upon you--something that penetrated inside your skull, battering against your brain, frightening you out of your beliefs, persuading you, almost, to deny the evidence of your senses. p. 80What is that if not a description of conscience--of that bullying spokesperson for society within our heads? Orwell takes great pains, in fact, to show Big Brother's means of getting inside citizens' heads in the manner of conscience, of controlling not just speech or actions, but thoughts. "[I]n the eyes of the Party there was no distinction between the thought and the deed." (p. 242) Orwell calls the governmental agency that gets inside people's heads the "Thought Police"--an immortally apt descriptor of bully conscience. If that were not enough to convince you of the connections between the political and the psychological in Orwell's writing, Orwell also assigns the Thought Police a rather unexpected preoccupation with sexuality.

The Party was trying to kill the sex instinct, or, if it could not be killed, then to distort it and dirty it. p. 66The sexual act, successfully performed, was rebellion. Desire was thoughtcrime. p. 68A member of the Thought Police even makes this startling prediction late in the novel: "We shall abolish orgasm." (p. 267) By contrast, Winston describes the chief virtue of "the Proles," who have largely escaped the Party's suffocating influence, in the following way:

They had held onto the primitive emotions which he himself had to relearn by conscious effort. p. 165The Thought Police are so aggressive in their puritanism that they demand a good number of thoughts be extirpated from consciousness entirely. To satisfy the Thought Police, "Zeal was not enough. Orthodoxy was unconsciousness." (p. 55) Party members are even equipped at their desks with "memory holes" for the incineration of intolerable information, usually data that might reflect the Party's practices of destroying facts--a practice that has all but "abolished" the entire temporal category of "the past." (p. 143) This is exactly the theory of conscience according to psychoanalysis: the conscience polices one's mental contents and rejects and suppresses those that offend conscience, such as, I hate my (big) brother, leaving behind a cleansed mental landscape of inoffensive contents like: I love my brother. Orwell all but tips us off that his political parable recapitulates an intrapsychic relation: "Your worst enemy, he reflected, was your own nervous system." (p. 64) And again: "one is never fighting against an external enemy but always against one's own body." (p. 103) 1984 is a fantasy more thoroughly paranoid than Invasion of the Body-Snatchers and more unrelievedly chilling than any of Kafka's, to which Orwell is directly or indirectly indebted. Both master Kafka and disciple Orwell concern themselves with the life of the individual inside the group--what might be called social psychology, which ought to be the psychology of conscience, since that's the internal institution that brokers relations between the individual self and society. While abuse by political or religious authorities is probably sufficient to corrupt a child's conscience, it's by no means necessary. I'd guess that's why Orwell's nightmare speaks to so many people who live more or less free of the sort of propaganda he describes. We all know what it is to feel guilt, suppress thoughts, and to run from the merciless Thought Police.

Published on December 12, 2012 09:22

December 9, 2012

Confessional Poetry

The Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath

The Collected Poems by Sylvia PlathYou'd think with all the cocktails, a cocktail party ought to be more fun than a hole in your head. Twitter has been called a global-scale cocktail party. Unfortunately, it seems to lack the essential ingredient of the cocktails. To put it another way, it's confessional poetry without the poetry.

What people sometimes call "confessional poetry," by contrast, may be personal and autobiographical, but it's neither a low artform nor symptomatic of commonplace vanity--at least not when it's practiced by a great writer like Sylvia Plath, author of some of my favorite poems. There's something deeply artistic going on in Plath's tortured imagination.

Confessional poetry, like much else that is modern, is not modern. Catullus wrote it in ancient Rome and there's poésie intime in France going back at least as far as Joachim du Bellay, who wrote in the sixteenth century. Du Bellay was an early advocate of writing in the vernacular (in his case, French) as opposed to Greek and Latin, because the vernacular was the language of direct experience--the language learned as a child through direct experience of the world.

Modern confessional poetry is part of this long tradition in paying heed to direct, personal experience, hard though it may be to look it in the eye.

View all my reviews

Published on December 09, 2012 20:59

December 2, 2012

Owl at Home in the Wilderness

Owl at Home by Arnold Lobel

Owl at Home by Arnold LobelAs a child, I knew children's author-illustrator Arnold Lobel for his fabulously funny, slyly philosophical Frog and Toad books. Lobel died young (downer), but he did create at least one other iconic animal character to help kids and adults alike through this bumpy journey called life: Owl.

Owl at Home shares the Frog and Toad books' virtues of empathy and humor, coziness and comically unfounded terror. Both of my kids loved Owl.

When he was 7, my older son saw me typing up my thoughts on Owl at Home and asked me, "Is this review going to go to the person who wrote the book?"

"No," I said authoritatively, "unfortunately the man who wrote it died a long time ago."

"How do you know he died?"

"Uh, I looked it up on the internet," I mumbled, ashamed.

"Did he make another chubby owl story?"

Alas, no. In any case, it would have been a tough act to follow. This is the finest group of chubby owl stories ever written. "He made the owl so chubby," my son said. The owl is indeed very cute and also, according to my kids, "very, very crazy" and "very stupid." But endearingly so. "Tear-Water Tea" is as funny as anything I've come across in a children's book, including the wickedly funny George and Martha. So is "Strange Bumps." It's perfect as is--one would almost hate to see a sequel involving an arrogant badger or annoying weasel (even as a fan of stories with a good annoying weasel). Owl's character is wedded to a confrontation with nature that he must carry out alone, without weasels and badgers to aid or hamper him. That's because, behind the children's illustrations and large type and simple words is a rather profound reflection of the confused and eager state of the human being alone with himself--and even of the human condition altogether, so eager and confused and alone in the wilderness.

Published on December 02, 2012 19:34

November 21, 2012

A High Wind in Jamaica

A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes

A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard HughesLike The Once and Future King and The Secret of Santa Vittoria, A High Wind in Jamaica straddles the disparate worlds of literature and entertainment, but it's darker than either of those other books--somewhat less malevolent than Lord of the Flies maybe, but mordant in a way that Lord of the Flies isn't because of the special skill with which Richard Hughes fixes reality on his imaginative screen. Hughes is a master realist like Christopher Isherwood. He had a whole litter of his own children eventually, but not until after he made this fine study of the mechanics of childhood imagination. Perhaps not being a parent he could play the naturalist even better, could watch the amoral clockworks of that imagination amorally like a naturalist watching a lion tear up a springbok by a baobab tree. The neatest trick is that he sees the children's imaginings and cognitive failings from without so that the narration itself is never for a moment mired in confused imaginings. Dramatic irony galore--we see what the children do not: a real world whose crass indifference to children is readily matched only by the children's tyrannical indifference to reality. A menagerie of animals fills up the book--a half-wild cat hunted by totally wild cats, a monkey with a gangrenous tail, a fussy pig, a goat with a "beard flying like a prophet's," etc.--and the animals seamlessly prefigure what will happen to the children with the subtlety of Ovid, to whom Hughes refers several times, and with the delicious sadism of a Martin Scorsese film.

View all my reviews

Published on November 21, 2012 09:08

November 13, 2012

The Second-Highest Heaven (Big Bang Part II)

Darrel Abel was born in Lost Nation, Iowa in 1911. He taught American literature at Purdue for many years, and at some point, working from the obscurity of Lisbon Falls, Maine, he produced a rather lovely little paper called "Robert Frost's 'Second-Highest Heaven'," which he published in 1980. The paper's title refers to a piece of Frost's prose on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Frost wrote:

Darrel Abel was born in Lost Nation, Iowa in 1911. He taught American literature at Purdue for many years, and at some point, working from the obscurity of Lisbon Falls, Maine, he produced a rather lovely little paper called "Robert Frost's 'Second-Highest Heaven'," which he published in 1980. The paper's title refers to a piece of Frost's prose on Ralph Waldo Emerson. Frost wrote:Everybody votes in heaven but everybody votes the same way, as in Russia today. It is only in the second-highest heaven that things get parliamentary.

Abel goes on to quote one of Frost's letters, which expresses a similar sentiment:

whatever great thinkers may say against the earth, I notice that no one is anxious to leave it for either Heaven or Hell. Heaven may be better than Hell as reported, but it is not as good as earth.

Frost was an American who knew the pioneer's feeling of diminution before the vast inhuman wilderness, "An emptiness flayed to the very stone," as he describes an abandoned, clear-cut piece of land in his brilliant 1923 poem "The Census-Taker." Like his predecessors Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville, he saw in the American situation a figure of the human situation in the universe itself. And like those former masters of American modernity, Frost refused despair any lasting purchase. They refused despair not because they were plucky and upbeat, but because they saw too deeply to ignore the true proportions between chaos and beauty, emptiness and humanness, in this complex, mysterious world of ours.

As Abel points out, Frost's famous poem "Desert Places" consciously rebuts Blaise Pascal in his terror at the emptiness between the stars. Here is Pascal worrying about space in his Pensées. You've heard of "penis envy" and "castration anxiety"--call this pensée anxiety:

When I consider the short duration of my life, an eternity that stretches behind and before, and the little space which I fill and even see, engulfed in the immensity of spaces I know not and which know not me, I am frightened and astonished at being here rather than there; for there is no reason why here rather than there, why now rather than then.... The eternal silence of the infinite spaces--it frightens me. Quoted in "Robert Frost's 'Second-Highest Heaven'" by Darrel Abel, Colby Library Quarterly, Vol. 16: Iss. 2, Article 3, 1980

The Big Bang can amplify the terror Pascal describes, which is in the first place not so easily dismissed. Paul Tillich, according to Abel, called such cosmic queasiness modern man's "real vertigo in relation to infinite space." Big Bang astronomy of course implies that those spaces, those desert places are not just infinite but stretching out, and so they're diminishing our physical stature in the cosmos. (To diminished stature, I say, so what? Short people achieve amazing things nowadays. Who cares how big or small we are in relation to the cosmos? Why should an electron care if it's smaller than the atomic nucleus? And would my funny bone feel any better if my elbows were the size of the Horsehead Nebula?) The vertigo is the more horrible thing; the Big Bang theory creates it by explaining so much without successfully delivering us from the painful tautologies with which we began our search for knowledge. It's the intellectual equivalent of whirling around and around.

Infinity and eternity aren't problematic because they're big (and they're not always big--a finite space may be infinitely subdivided), but because they're at once inescapable and nonsensical aspects of the cosmos. Mathematics seems to acknowledge as much since the symbol for infinity, ∞, also means "undefined." (As in 20 divided by zero = ∞.) The universe appears to have begun at a point in time. But how does something come from nothing? What was before? Something else? Some other universe? None of the alternatives appeal to common sense, and so the Big Bang theory pictures a universe whose perfectly comprehensible laws lead to perfectly incomprehensible conundra of origins and endings, limits and infinity. That's how I interpret Tillich's vertigo, and the theme of Frost's poetry--in Abel's words, "man's lostness in space." Not only do we not understand the limits of the universe in time and space, but it seems they are constitutionally inaccessible to understanding. They are non-parameters, they are outside reason and experience, yet reason and experience lead us straight to their door.... This is a miserable and untenable state of affairs.

In the last decades, the mental health field has often and without good reason blurred the traditional medical dividing line between symptom and diagnosis. I would argue that pensée anxiety, Tillich's vertigo, Big Bang-o-phobia, etc., is not a diagnosis. It's not even its own symptom. Rather, it's but one instance of a more commonplace problem I call "under-the-hood nausea." (For a fuller discussion of under-the-hood nausea, here is another blog I wrote on the subject. Under-the-hood nausea, in turn, is but a manifestation of neurosis.)

Science reaches out, by instruments and inferences, into planes of reality that exist on different scales from our own. This is what creates under-the-hood nausea. The Big Bang was named by Fred Hoyle, an important physicist who happened to despise the theory and applied the phrase "Big Bang" in derision. But the theory is perhaps rightly named in the sense that it bashes you over the head with under-the-hood nausea like nothing else. It's looking under the hood of the cosmos, and just as looking inside the body at the guts makes some people feel sick, looking under the hood of the cosmos can fill you with vertiginous questions: What is infinity? Why is there something rather than nothing? Is there a god? If there is, can I still masturbate? Why are so many cosmologists named George?

Scientists must look at reality on every plane, at every magnification, but if we can't relate our findings to our own scale, our own plane, then the work of comprehension isn't done. If we can't interpret and appreciate our knowledge in human terms, then the science may have the effect of urging us on in our despair--despair which belongs to our own homely little world of birth and death and not to the vacuous spaces between the stars. Help me, Mr. Frost:

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars--on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

Wittgenstein was a very fine doctor for treating sickening cosmic questions. He suggested that such questions must have bad syntax--just like the meaningless proposition twenty divided by zero. If you look out into the cosmos and feel despair, remind yourself that despair is 100% human. If our understanding of physics is too incomplete right now to relate the cosmic to the quantum to the human scale of affairs, our psyches do it for us in a crude way--with despair. Yet the more we look, the more order we see in the universe. In that sense, the universe appears to be a more and more hospitable place the more we learn about it--a more human place, since humanity and life are founded on a principle of order and the development of more of it.

Fred Hoyle, the Big Bang skeptic, discovered how heavy elements are forged in the furnaces of the stars and he did it by an anthropic inference: we exist; we're made of carbon; therefore nucleosynthesis of carbon must occur; therefore stars must have a way of doing it; therefore certain isotopes of helium and beryllium must react quickly to form an excited conformation of carbon-12. He was right. Multiple generations of stars must refine lighter elements in their breasts to make heavier ones like carbon. The stars are our mothers and fathers. The universe has music in it. It has despair in it. But it's all ours.

Like the joke says:

There was a costume party where everybody was instructed to dress as an emotion. The party hosts greeted the first guest, who was dressed from head to toe in red, and asked him, "What emotion are you supposed to be?" He said, "Rage." The next guest was dressed all in green--green tights, green leotard, a green hat. When they asked what emotion she was supposed to be, she said, "I'm envy." Then a guy came to the door completely naked, with a pear stuck on the end of his penis. The hosts asked, "What emotion are you?" He said, "I'm fuckin' despair."

Published on November 13, 2012 15:29

November 1, 2012

Begin the Cosmic Beguine (Big Bang Part I)

Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe by Simon Singh

Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe by Simon SinghMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

It generally takes a child no more than three or four ingenuous questions to reach a humbling horizon beyond which no intellect, whether adult or child or Stephen Hawking, has passed: the question of how the universe began. Whatever we learn about the past, the answer to the next question--what came before that--rears up on the horizon, ever out of reach. I used to lie in bed as a child and imagine infinity until my head hurt.

We do know more than ever before, however, and some of that knowledge has arrived within my own lifetime. Books really do help, especially when written by a science writer par excellence like Simon Singh, who sets out to teach you the subject for real. Singh doesn't water everything down to the point where it makes no sense. He trusts his readers' intelligence and their natural childlike curiosity, and he has the writerly skill to make the real science into a fascinating story--a story which begins not with a bang but a person--Einstein.

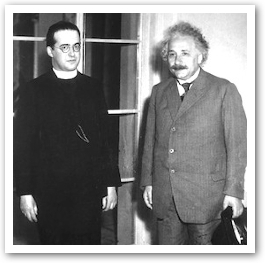

Einstein's theory of relativity predicts that matter causes the space of the universe to contract or expand--a dynamic notion of space that cannot be tested by everyday experience, but can be (and has been) tested by data collected from telescopes. Around 1920, Jewish-Russian mathematician Alexander Friedmann applied Einstein's equations to cosmology in order to predict what was happening to the size of the whole universe; he predicted it was expanding. Georges Lemaître (a physicist who was also a Catholic priest, pictured next to Einstein in his white collar!)

did the same and deduced that if the universe has expanded, it must once have been compact. The idea was not that the matter of the universe exploded like shrapnel from a bomb (one reason "Big Bang" is an imperfect name), but rather that the empty space of the universe itself was once compact and ever since has been stretching out like silly putty.

did the same and deduced that if the universe has expanded, it must once have been compact. The idea was not that the matter of the universe exploded like shrapnel from a bomb (one reason "Big Bang" is an imperfect name), but rather that the empty space of the universe itself was once compact and ever since has been stretching out like silly putty. The general theory of relativity is evidently very difficult to translate into plain English, and I don't understand it any further than physicist John Wheeler's famous statement that "Matter tells space how to curve, and curved space tells matter how to move." (It also tells light how to move. I'd like to see if it could get my kids to put their shoes on.) I do know this: whereas matter can't move through space faster than light, space itself can change size faster than the speed of light. It's often said that light from billions of light years away is showing us something billions of years in the past; light from afar is very old; that's putatively because the light has been traveling for billions of years to get to us. I never understood how this could be, since I assumed that distant galaxies must have taken billions of light years to get so far away from our common Big Bang point of origin in the first place. Singh does not address this particular question, but other sources confirm that the universe seems to have expanded much faster than light in the beginning; I presume that's how the infant universe could have blown out to a size billions of light-years across in less than billions of years, and how light from 14 billion light years away therefore could show us baby pictures of the universe. At any rate, Edwin Hubble's observations of the skies, made on freezing nights through a giant telescope in Pasadena, and his analyses of observed Doppler shifts of spectra emitted by familiar elements like helium in distant stars, confirmed that the universe is indeed expanding, with the speed of expansion apparently increasing at farther distances out.

More support for the idea of the Big Bang came from particle physics. Russian refugee George Gamow concluded that the relative abundances of elements in the universe (90% hydrogen, 10% helium, trace amounts of heavier elements, as determined by spectroscopy on the heavens) could best be explained if the universe's matter was once a condensed ball of plasma hotter and more pressurized than that inside stars--he called this universal primordium of subatomic particles ylem. Gamow's young collaborator Ralph Alpher made mathematical models of the primordial universe; they showed that the early universe would have had the right conditions for the right length of time to support "nucleosynthesis" of 10% of the loose protons into helium. Then, with colleague Robert Hermann, Alpher theorized that the early universe should have cooled from plasma to gas 300,000 years after creation, an event called "recombination" (because it was now cool enough for electrons to "recombine" with atomic nuclei instead of flying all over the place? but were they ever combined before that?); they predicted that recombination should have allowed the early universe to radiate light instead of merely scattering it and the light should still be flying through space in every direction and that the expansion of the universe should by now have stretched the wavelength of the extant light of recombination to the point where it would be in the microwave part of the electromagnetic spectrum--the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB radiation).

At this point the Nobel committee was paying serious attention to the Big Bang theory. In 1965 Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, who worked for Bell Labs in New Jersey, confirmed the existence of the CMB radiation with a radio telescope and later won the Nobel prize. Finally, George Smoot got NASA to launch a satellite with a radiometer on it so that he could look for miniscule variations in the CMB radiation. These would reflect the existence of condensates of matter in the early universe--the precursors to today's stars and galaxies; NASA launched it in 1989, the radiometer detected it, Smoot too won a Nobel prize for it. I am pretty sure that the variations in the CMB radiation do not explain why half my noodles are hot and half are cold when I reheat a bowl of pasta. Nonetheless, I blame the Big Bang. The end of the story of how we understand the beginning.

There are so many wonderfully human aspects to this history of an idea. The history of astronomy as Singh tells it is a history of passionate, suffering dreamers, of political refugees converging on England and America where they could think in peace. 20th century physics is also a history of the Jews, whose numbers in the Big Bang story far exceed those of helium in the stars (Einstein, Friedmann, Alpher, Hermann, and Penzias are among the Jewish free thinkers who built this progressive theory). The Big Bang is both an elucidation and a revelation of mysteries and cosmic order. Why then, does it hold such potential to make your head hurt and your soul ache with a sense of the empty, senseless, inhumanity of the universe? I feel this anxiety, yet I don't trust it. See Part II.

View all my reviews

Published on November 01, 2012 07:55

Austin Ratner's Blog

Untimely thoughts on books both great and supposedly great.

- Austin Ratner's profile

- 32 followers

Austin Ratner isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.