Austin Ratner's Blog, page 4

September 30, 2012

Ovid Part IV: Metamorphose This

The speaker of Ovid's "Contrite Lover" elegy in Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: "What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?" (Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker "feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up...." (Fränkel, Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid's representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:

The speaker of Ovid's "Contrite Lover" elegy in Amores reflects on a quarrel in which he struck his lover. Full of remorse, he asks this of his own hands: "What have I to do with you, servants of murder and crime?" (Amores I, 7, 27). As Hermann Fränkel puts it, the speaker "feels estranged from his own self of a moment before. His identity is broken up...." (Fränkel, Ovid: A poet Between Two Worlds, pp. 20-21) The great classical scholar considers Ovid's representation of inner conflict a historic literary achievement:[I]t was an unheard-of novelty for the ancients that a person should no longer feel securely identical with his own self.... There is no sign of a previous emergence of these possibilities; Ovid took them for granted and used them freely in his poetry.... [W]ith the self losing its solid unity and being able half to detach itself from its bearer, a fundamental shift had taken place in the history of the human mind. Frankel, p. 21

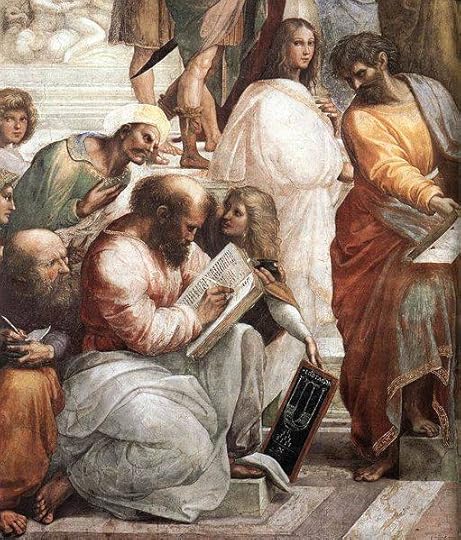

Before Ovid came along, Plato and other ancient philosophers had postulated a self divided by competing faculties of passion and reason. But who had ever represented the subjective experience of these internal divisions with Ovid's level of modern realism? Even among later poets, who but Shakespeare has represented our divided consciousness so well as Ovid?

Indeed, in Ovid's representations of mental life, schisms of identity and clashes between wishes and realities precipitate solutions where a troubling aspect of self or world is rejected from consciousness. "Time and again," Fränkel writes of the Amores, "we find Ovid bent on concealing from his own eyes a disagreeable fact; but he also sees to it that the cloak is transparent." (Fränkel, p. 31) In the Heroides, one of Ovid's heroines, Phyllis, attests to the same phenomenon: "one is slow to give credence to that which brings pain.... Often I lied to myself...." (quoted in Fränkel, p. 42)

True, there are antecedents to Ovid's notion of denial, too. Consider his telling of the famous story of Jupiter and Io, first in the Heroides and again in the Metamorphoses. Ovid seems deliberately to echo Sophocles. "What is the reason for your flight?" Ovid writes of the nymph Io in the Heroides. (To hide his affair from Juno, Jupiter has turned Io into a cow and Io goes mad trying to run from her new form when she cannot.) "You will never escape from your own face.... You are the same who both pursues and flees. It is you who lead yourself, and you go where you lead." (quoted in Fränkel p. 79) Whether or not Ovid intended it, the lines certainly call to mind Teiresias's stunning words to Oedipus in Oedipus Rex: "I say you are the murderer of the king whose murderer you seek."

Ovid, however, accomplishes with his fantastic tales what Sophocles did not attempt: he converts the ancient wisdom written on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi--gnothi sauton in the original Greek (nosce te ipsum in Latin, "know thyself" in English)--into psychological realism that not only depicts inner conflict and denial in personal terms, but actually examines what Freud later called defense mechanisms.

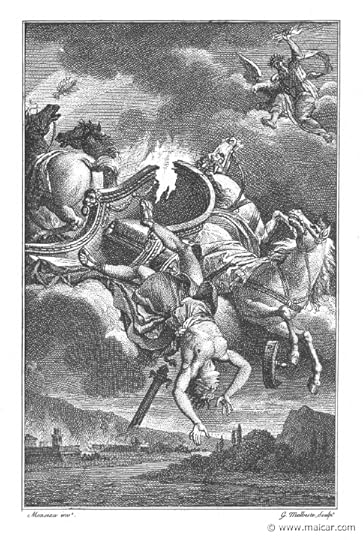

That is to say, not all transformation in Metamorphoses is supernatural. In many cases Ovid in fact dispenses with the fantastical metamorphoses and depicts in straight realist terms an emotion being actively revised or altered by another. For example in Book II Phaethon asks his father Apollo whether Clymene (Phaethon's mother) lied when she said Apollo was his father. His exact words are nec falsa Clymene culpam sub imagine celat (Metamorphoses, II, 37), "if Clymene is not hiding her shame beneath an unreal pretence." Here Ovid makes the pattern of pain and emotional flight more intricate, more subtle: the particular pain in this case is shame; the particular means of evasion is hiding.

At times Ovid upstages Freud to the degree that he uses Freudian terms like "repression" and "transference" in connection with pretty much the same phenomena Freud sought to describe.

erebuit Phaethon iramque pudore repressit, "Phaethon blushed and repressed his anger in shame." (I, 755)

Iovis coniunx ... a Tyria collectum paelice transfert in generis socios odium, "the wife of Jove had now transferred her anger from her Tyrian rival to those who shared her blood." (II, 256-259)

The Phaethon episode in Book II, one of the best in the Metamorphoses, tracks Apollo's changing emotions in sequence like a psychoanalyst would. After his son Phaethon's death, Ovid tells us, lucemque odit seque ipse diemque datque animum in luctus et luctibus adicit iram officiumque negat mundo, or "He hates himself and the light of day, gives over his soul to grief, to grief adds rage, and refuses to do service to the world." (Metamorphoses, II, 383-385)

After Jupiter goads Apollo into climbing back into the chariot to light the world, Ovid writes: Phoebus equos stimuloque dolens et verbere saevit (saevit enim) natumque obiectat et inputat illis, "in his grief Phoebus savagely plies the horses with lash and goad (so savagely), reproaching and taxing them with the death of his son." (II, 399-400) It's true that the horses were an instrument in Phaethon's demise, but Apollo knows that they are innocent beasts, that the fault lies most of all with Phaethon himself and with Jupiter, who threw the thunderbolt that killed him--and who, after making a brief apology, had the audacity to threaten Apollo if he didn't resume his duties. Ovid implies quite unambiguously that Apollo whips the horses in Jupiter's place, in Phaethon's place, in his own place.

When Jupiter rapes Callisto, one of Diana's maidens, Ovid writes, huic odio nemus est et conscia silva "She loathed the forest and the woods that knew her secret." (II, 338) She seems to hate the woods in place of Jupiter (again), because Jupiter is too terrible to attack directly. Perhaps Callisto also hates the woods in place of her own guilt. Ovid continues, quam difficile est crimen non prodere vultu! "How hard it is not to betray guilt in the face!" (II, 447) Freud teaches us that guilt is a major, if not the major, stimulus to repression. Guilt causes people to hide emotions from themselves and from others. More often than not, transformation of ideas and affects does the hiding. Shakespeare knew this before Freud. And Ovid evidently knew it before either one of his great intellectual heirs, as transformative defense mechanisms of displacement and identification abound in his Metamorphoses. I found it most interesting that Ovid describes Nyctimene, a woman who slept with her father and was punished by turning into a bird, as being conscia culpae--literally "conscious of her guilt." (II, 593) It implies she might also have been unconscious of it. Ovid would have had little trouble understanding Shak and Freud, and it's obvious that "Ovid's amazing candor" (Fränkel, p. 58) imparted much psychological wisdom to later ages.

September 2, 2012

Ovid Part III: Thought Letters

Ovid was "revered among Elizabethan pedagogues" according to R.W. Maslen (Shakespeare's Ovid, p. 17). It sounds like a terrible fate, to be revered by a pedagogue, let alone a bunch of Elizabethan ones. I don't know for certain what happens if one reveres you, but if one kisses you, I think you get warts. Or am I thinking of frogs? In any case, like many Elizabethans, Shakespeare purportedly encountered Ovid in grammar school. The Roman poet seems to have left an impression on the Stratford boy who lived an age and a half later. The Metamorphoses in fact figures into Shak's early tragedy Titus Andronicus in an unusual way for a Shakespeare play: a physical copy of Ovid's book appears onstage. Young Lucius is reading it and his aunt Lavinia, who like Philomela in the Metamorphoses has had her tongue cut out, tries to communicate her own story by turning the pages to the story of Philomela and Procne. Philomela had to weave a tapestry to communicate, but Lavinia's attackers had also chopped her hands off, so in place of weaving a tapestry, she uses Ovid's story about the tapestry!!! Shak famously ate up source material both high and low and incorporated it all into his works, but I find it striking that the Metamorphoses alone (?) turns up in this undigested form--whole, as it were, with its binding still on it like some piece of literary roughage that even Shakespeare's omnivorous guts could not fully break down. Titus Andronicus does not incorporate Ovid so much as embrace him like a peach pit in the belly of a gull, or quartz in the belly of an oyster. With Ovid in his craw, Shak made quite a few pearls; Ovid not only provided Shakespeare with source material that turns up in Titus Andronicus, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Tempest, and many other plays, but--as it seems to me in my amateur scholarship--he also provided to Shakespeare some of his most important themes and methods. It looks to me like Ovid (and his Greek and Roman antecedents), not Montaigne or Shakespeare, is more nearly the inventor of the inward-looking soliloquy. First, Ovid brilliantly portrayed the mind talking to itself in his Heroides, using what Hermann Fränkel calls "thought letters." (Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds, p. 37) Then he developed that technique into totally "Shakespearean" inner debates in the Metamorphoses. Virgil too narrates characters' thoughts, and even their inner debates, such as when the jilted Dido contemplates suicide; repeatedly gods and mortals in The Aeneid 'turn things over in their breasts' as though the heart could buffet with a convoluted motion like that of the sea. But even when Virgil spies on his characters' thoughts, he seems to do so from a more Olympian height. Ovid brings, I think, an unprecedented focus and worldly detailed comprehension to inner life. He's also got a fairly systematic theory of psychological transformation, the like of which I am not aware of in Virgil or Homer or any place, really, besides Shakespeare, who evidently absorbed Ovid's philosophy and applied it in his own work. Fränkel notes that Ovid's "thought letters" derive their character in part from the suasoria--the rhetoric of persuasion--he had learned while training to be a lawyer or civil servant (as his father wished him to, of course). But according to Fränkel, Ovid puts suasoria to a use that was fairly new to literature. He has the eponymous heroines of the Heroides draft letters to lovers who cannot or will not reply, so that the letters effectively rehearse conversations or arguments inwardly without enacting them. The stakes in each case are only this: love. Fränkel describes a thought letter as

Ovid was "revered among Elizabethan pedagogues" according to R.W. Maslen (Shakespeare's Ovid, p. 17). It sounds like a terrible fate, to be revered by a pedagogue, let alone a bunch of Elizabethan ones. I don't know for certain what happens if one reveres you, but if one kisses you, I think you get warts. Or am I thinking of frogs? In any case, like many Elizabethans, Shakespeare purportedly encountered Ovid in grammar school. The Roman poet seems to have left an impression on the Stratford boy who lived an age and a half later. The Metamorphoses in fact figures into Shak's early tragedy Titus Andronicus in an unusual way for a Shakespeare play: a physical copy of Ovid's book appears onstage. Young Lucius is reading it and his aunt Lavinia, who like Philomela in the Metamorphoses has had her tongue cut out, tries to communicate her own story by turning the pages to the story of Philomela and Procne. Philomela had to weave a tapestry to communicate, but Lavinia's attackers had also chopped her hands off, so in place of weaving a tapestry, she uses Ovid's story about the tapestry!!! Shak famously ate up source material both high and low and incorporated it all into his works, but I find it striking that the Metamorphoses alone (?) turns up in this undigested form--whole, as it were, with its binding still on it like some piece of literary roughage that even Shakespeare's omnivorous guts could not fully break down. Titus Andronicus does not incorporate Ovid so much as embrace him like a peach pit in the belly of a gull, or quartz in the belly of an oyster. With Ovid in his craw, Shak made quite a few pearls; Ovid not only provided Shakespeare with source material that turns up in Titus Andronicus, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Tempest, and many other plays, but--as it seems to me in my amateur scholarship--he also provided to Shakespeare some of his most important themes and methods. It looks to me like Ovid (and his Greek and Roman antecedents), not Montaigne or Shakespeare, is more nearly the inventor of the inward-looking soliloquy. First, Ovid brilliantly portrayed the mind talking to itself in his Heroides, using what Hermann Fränkel calls "thought letters." (Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds, p. 37) Then he developed that technique into totally "Shakespearean" inner debates in the Metamorphoses. Virgil too narrates characters' thoughts, and even their inner debates, such as when the jilted Dido contemplates suicide; repeatedly gods and mortals in The Aeneid 'turn things over in their breasts' as though the heart could buffet with a convoluted motion like that of the sea. But even when Virgil spies on his characters' thoughts, he seems to do so from a more Olympian height. Ovid brings, I think, an unprecedented focus and worldly detailed comprehension to inner life. He's also got a fairly systematic theory of psychological transformation, the like of which I am not aware of in Virgil or Homer or any place, really, besides Shakespeare, who evidently absorbed Ovid's philosophy and applied it in his own work. Fränkel notes that Ovid's "thought letters" derive their character in part from the suasoria--the rhetoric of persuasion--he had learned while training to be a lawyer or civil servant (as his father wished him to, of course). But according to Fränkel, Ovid puts suasoria to a use that was fairly new to literature. He has the eponymous heroines of the Heroides draft letters to lovers who cannot or will not reply, so that the letters effectively rehearse conversations or arguments inwardly without enacting them. The stakes in each case are only this: love. Fränkel describes a thought letter as a special kind of letter, the kind which in actual fact we rarely put down on paper and would hardly ever drop in the mailbox. Nevertheless we did carefully prepare that letter in our own mind, silently arguing out the issue with our remote and unwilling partner, perhaps for hours on end; anticipating his objections and thwarting his evasions; and with each repetition we improved on the clarity of our reasoning and the moral force of our appeal, until eventually we had perfected our unwritten letter so as to render it, on its own merits, irresistibly convincing. Unfortunately, we had no means of communicating with the person we were thus addressing; or, if he were to receive such a letter, he would not be greatly impressed, because he was already prejudiced in the matter; or he would not open it, because he was not interested in anything we had to say; or, perhaps, it was not proper for us to tell him how we felt, for tact and shame forbade it. For one or another of these reasons, our letter never materialized; and yet for our own sake we worked it out mentally.Fränkel, pp. 36-37

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid takes the thought letter one step further. Characters now argue in their heads not with another but with themselves. In Book X, Ovid writes of a girl, Myrrha (namesake for the myrrh tree and mother of Adonis), whose incestuous love for her father torments her. See how "Shakespearean" is her soliloquy?

She indeed is fully aware of her vile passion and fights against it and says within herself [secum inquit (X, 320)], "To what is my purpose tending? What am I planning? O gods, I pray you, and piety and the sacred rights of parents, keep this sin from me and fight off my crime, if indeed it is a crime. But I am not sure, for piety refuses to condemn such love as this. Other animals mate as they will, nor is it thought base for a heifer to endure her sire, nor for his own offspring to be a horse's mate; the goat goes in among the flocks which he has fathered, and the very birds conceive from those from whom they were conceived. Happy they who have such privilege! Human civilization has made spiteful laws and what nature allows, the jealous laws forbid. And yet they say that there are tribes among whom mother and son, daughter with father mates, and natural love is increased by the double bond. Oh wretched me, that it was not my lot to be born there, and that I am thwarted by the mere accident of place! Why do I dwell on such things? Avaunt, lawless desires! Worthy to be loved is he, but as a father.... It is well to go far away, to leave the borders of my native land, if only I may flee from crime; but an evil passion keeps me from going.... But you, while you have not yet sinned in body, do not conceive sin in your heart, and defile not great nature's law with unlawful longing. Grant that you wish it: facts themselves forbid."X, 319-355

Of the thought letters, Fränkel writes, "The idea of verse epistles of this sort was new, and Ovid felt justly proud of his originality." (Fränkel, pp. 45-46) Ovid accomplished enough to satisfy his grand ambitions, and he ought not to be overshadowed by his genius pupil Shakespeare. In the final poem in his third book of Odes, Horace boasts that his poetry will outlive any manmade monument: Exegi monumentum aere perennius. ("I have made a monument more lasting than bronze.") Ovid makes a similar boast at the end of the Metamorphoses:

Iamque opus exegi, quod nec Iovis ira nec ignis

nec poterit ferrum nec edax abolere vetustas.

...perque omnia saecula fama,

siquid habent veri vatum praesagia, vivam.And now my work is done, which neither the wrath of Jove, nor fire, nor sword, nor the gnawing tooth of time shall ever be able to undo.... And through all ages in fame, if the prophecies of poets have any truth, I shall live.

XV, 871-872, 878-879

Ironically it's the truths in Ovid's poetry, not his prophecy, that made the prophecy come true.

August 29, 2012

Ovid Part II: Ovid and Science

Book XV is more than the coda to the Metamorphoses. It too is a transformation. Here at the end of Ovid's poem, he turns from fable to the real historical figure of Julius Caesar so that mythology itself metamorphoses into history. In this same Book, Ovid invites Pythagoras into the narrative as spokesman for the new age, offering a vision of the world that seems to be shedding itself of the old mystic fog even as we read. As Simon Singh tells us in his book on the Big Bang (Big Bang, p. 7), Pythagoras helped initiate the "new rationalist movement" that dawned on the world in the 500s B.C.E. And Ovid shows he's quite alert to the transition into modernity which began with the Greek Enlightenment and continued with the Roman one of his own day; such an awareness explains the sophistication with which Ovid re-invented the old fables as realist studies of the intricacies of emotion and behavior.

Book XV is more than the coda to the Metamorphoses. It too is a transformation. Here at the end of Ovid's poem, he turns from fable to the real historical figure of Julius Caesar so that mythology itself metamorphoses into history. In this same Book, Ovid invites Pythagoras into the narrative as spokesman for the new age, offering a vision of the world that seems to be shedding itself of the old mystic fog even as we read. As Simon Singh tells us in his book on the Big Bang (Big Bang, p. 7), Pythagoras helped initiate the "new rationalist movement" that dawned on the world in the 500s B.C.E. And Ovid shows he's quite alert to the transition into modernity which began with the Greek Enlightenment and continued with the Roman one of his own day; such an awareness explains the sophistication with which Ovid re-invented the old fables as realist studies of the intricacies of emotion and behavior. Not for a moment, of course, would Ovid take water nymphs and miracles for anything but figments of imagination. We have his own word for it that the transformations of his Metamorphoses are not to be believed (Tristia II, 64).... And yet he gave ancient mythology its unexcelled, final, comprehensive expression. Hermann Fränkel, Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds, p. 89

The human heart and its world unite in Ovid's scientific mind. Both art and science depict change--art through drama, and science through calculus; art the changes that pertain to people's mental introjections, and science the changes that pertain to the mineral world of humanity's origin and habitation.

Numa, the second king of Rome, we are told in Book XV, wishes to know "what is Nature's general law," or quae sit rerum natura (XV, 6), a phrase that echoes the title of Lucretius's great scientific-minded poem De rerum natura. The poem influenced Virgil, Horace, and Ovid, and we can only read it ourselves because Poggio Bracciolini rescued the last remaining copy of De rerum natura from a decrepit monastery in the 15th century. Similar measures were required for the first edition of my physiology textbook.

The main law of Nature, according to Ovid, is caelum et quodcumque sub illo est, inmutat formas, tellusque et quicquid in illa est (XV, 454-455): "the heavens and whatever is beneath the heavens change their forms, the earth and all that is within it."

Throughout the poem, Ovid proves himself an astute observer and thinker about the changing natural world, an ambassador like Lucretius for the enlightened scientific values of the great Epicurus.

For example, he suggests that the earth is round and that it was shaped into an orb, glomeravit in orbis (I, 35), by a cosmological force--today we'd call that gravity. He knew that waves are caused not by Neptune but by wind (I, 36-37). He says that what look like falling stars are actually something else (II, 321-322). In a simile in Book II, he gives a fairly modern account of cancer: utque malum late solet inmedicabile cancer serpere et inlaesas vitiatis addere partes "And, as an incurable cancer spreads its evil roots ever more widely and involves sound with infected parts...." (II, 825-826) When he writes sanguine defectos cecidit conlapsus in artus (V, 96), or "he fell fainting, his limbs all drained of blood," he gives a modern account of syncope that implies the incumbency of consciousness upon blood pressure. He says, quite rightly, that rainbows are caused by sunlight passing through wet air (VI, 63-64). With an appreciation for embryology, he asserts that "in its mother's body an infant gradually assumes human form," or as he puts it, hominis speciem materna sumit ... infans (VII, 125-126). He describes what sounds like a zoonotic plague in Book VII with a sophistication both epidemiological and epistemological; "Since the cause of the disease is hidden," he writes, "the place itself is held to blame" (VII, 576). Always Ovid considers natural first causes, whether known or unknown: a river swells due to snowmelt (VIII, 556-557); snow in turn forms from rain chilled by cold air (IX, 220-222). Further discussion of the elements reflects Ovid's fairly accurate understanding of density and its importance to the phases of matter. (XV, 237-251)

His metaphors and details frequently draw on fine naturalistic observations: of lunar eclipse (IV, 330-332); of sunrays (IV, 347-349); of translucent glass (IV, 355); of eagles and sea anemones preying, and ivy twining (IV, 362-367); of horticultural practices like grafting (IV, 375-376); of bats (IV, 414-415); of rainbows (VI, 61-67) (his metaphor on rainbows, which he calls upon to describe the fineness of Athena and Arachne's work weaving tapestries, expresses an aesthetic appreciation for detailed imitations of nature); of exposed, palpitating entrails, salientia viscera (VI, 390); the way that prey reverse course to evade a predator (VII, 782-784); the way a boar (in this case, Calydonian) whets its tusks on a tree trunk (VIII, 369-370); storm and wreck at sea (XI, 475-572).

As the poem nears its conclusion, these observations yield a prescient theory of geologic and biologic change that begins to sound like the theory of evolution. He discusses erosion (XV, 262-272) and other changes in the landscape and moves on to the metamorphoses that take place in the animal world (XV, 361-390): carcasses breed maggots; flightless larvae become mature airborne insects; tadpoles become frogs; blobby babies grow into well-formed adults; eggs become birds. Sea creatures at one point (XIII, 936-937) come forth onto land in a passage that seems to contain some intuition about that moment in evolutionary history when lungfish learned to walk on tidal mudflats. Perhaps Ovid was influenced by Horace, who wrote:

When living creatures crawled forth upon primeval earth, dumb, shapeless beasts, they fought for their acorns and lairs with nails and fists, then with clubs, and so on step by step with the weapons which need had later forged, until they found words and names wherewith to give meaning to their cries and feelings.

Horace, Satires, I, iii, 99ff

One gets the sense that the Roman intelligentsia had an altogether more sophisticated grasp of the world around them than many of the voters who decide elections two millennia later.

August 19, 2012

Ovid Part I: A Delicious Fränkelburger

The middle of summer -- July -- if you walk west on Montague Street toward the harbor at around 6:30 in the evening, carrying your bag of black plums, the harbor is a gigantic cauldron of fire that sets upon every head a backlighting halo. It's like something out of On Golden Pond except that it smells like garbage and there's dogshit all over the sidewalk. You see more fire dripping from a top floor air conditioner and exploding on the awning of an Italian restaurant like ore dripping from a smelter. You see girls with bare arms and bare legs. Up, down, and sideways, you see boobs boobs boobs. Ah, summer! "For there is no hardier time than this," Ovid writes in his Metamorphoses, "none more abounding in rich, warm life." Bk XV, ll. 207-208. In August you drive to the beach with the windows down and the "where do we go now" part of "Sweet Child o' Mine" breaking down on the car stereo at an almost painful volume, and you have a vanilla ice cream cone in each hand and are driving with your knee (not really, I can't digest milk, but you get the idea), and you're watching the girls with their bikinis and their cover-ups, and you're thinking to yourself, "If Norman Mailer was here, I would karate chop him in the neck" and you don't even pity Slash for being less of a bad-ass than you are. And your boys are in the back seat in their bare feet, without their seatbelts on and you don't even care. Or maybe you have no urge to karate chop Norman Mailer and maybe you ride a bike. Anyway, I am more bad-ass than Slash because, in addition to sometimes not forcing my shoeless kids into their seatbelts, I read Ovid's Metamorphoses this summer, as well as Hermann Fränkel's magnificent Sather Lectures on Ovid, given at Berkeley 65 or 70 years ago. Frankel calls Ovid "a poet between two worlds," because in many ways he is the first truly modern writer--a writer with an enlightened, scientific, expressly psychological worldview--even more so than his great predecessor Virgil:

The middle of summer -- July -- if you walk west on Montague Street toward the harbor at around 6:30 in the evening, carrying your bag of black plums, the harbor is a gigantic cauldron of fire that sets upon every head a backlighting halo. It's like something out of On Golden Pond except that it smells like garbage and there's dogshit all over the sidewalk. You see more fire dripping from a top floor air conditioner and exploding on the awning of an Italian restaurant like ore dripping from a smelter. You see girls with bare arms and bare legs. Up, down, and sideways, you see boobs boobs boobs. Ah, summer! "For there is no hardier time than this," Ovid writes in his Metamorphoses, "none more abounding in rich, warm life." Bk XV, ll. 207-208. In August you drive to the beach with the windows down and the "where do we go now" part of "Sweet Child o' Mine" breaking down on the car stereo at an almost painful volume, and you have a vanilla ice cream cone in each hand and are driving with your knee (not really, I can't digest milk, but you get the idea), and you're watching the girls with their bikinis and their cover-ups, and you're thinking to yourself, "If Norman Mailer was here, I would karate chop him in the neck" and you don't even pity Slash for being less of a bad-ass than you are. And your boys are in the back seat in their bare feet, without their seatbelts on and you don't even care. Or maybe you have no urge to karate chop Norman Mailer and maybe you ride a bike. Anyway, I am more bad-ass than Slash because, in addition to sometimes not forcing my shoeless kids into their seatbelts, I read Ovid's Metamorphoses this summer, as well as Hermann Fränkel's magnificent Sather Lectures on Ovid, given at Berkeley 65 or 70 years ago. Frankel calls Ovid "a poet between two worlds," because in many ways he is the first truly modern writer--a writer with an enlightened, scientific, expressly psychological worldview--even more so than his great predecessor Virgil: [H]e was leaving behind him Antiquity as we know it and traveling on the path to a new age of mankind.... [H]e candidly voiced his experiences in the same modern spirit in which he lived through them, ignoring established traditions and the code of wary discretion. Fränkel, p. 23.Ovid's reputation has suffered under the general hailstorm of postmodernism raining down on the classics, but he's suffered much more undervaluation than Homer and Virgil ever have, in part because he's been misconstrued as a mere anthologist of old myths and been outshone by the many artists whose careers he shaped and in the first place made possible. He is no Joseph Campbell. On the contrary, his entirely original and modern versions of old myths are undoubtedly the main reason that later artists have been so interested in them. As Fränkel says, "the poet has turned a primitive fiction into a symbol for a substantial truth." (p. 78) Ovid's "metamorphoses"--transformations that sometimes punish and reflect crimes--provided to Dante the contrapasso method that's the chassis for the Inferno. Ovid not only influenced Shakespeare but invented the inward-looking soliloquy for him. Though he doesn't appear in Henri Ellenberger's comprehensive history of the unconscious and though Freud barely refers to him, Ovid is probably the first and most influential commentator on unconscious ideation. In its psychologically sophisticated fantasy, his work draws closer to modern magical realism than anything else in the ancient world, a fact which may be reflected in Kafka's conspicuously Ovidean title, The Metamorphosis. John Donne's famous poem "The Sun Rising," which Carol Rumens calls "one of the most joyous love poems ever written" is very clearly influenced by Ovid's elegy "The Dawn." Renaissance painters used the Metamorphoses like they did the Bible, and in fact, knowing Ovid through his autobiographical works (like Ex Ponto and Tristia, almost unique in the ancient world) is equivalent to knowing the human authors of the Bible. My Fränkel edition of Ovid: A Poet Between Two Worlds is literally stained with summer delight; it has a faint discoloration on its green cloth binding from where a delicious Prime Meats hamburger exploded on it. (I have since sterilized the spot so you can't get E. coli from reading about Ovid.) The book has a stamp on the bottom that says "Niagara University Library" and the card catalog stamps say it was taken out 4 times between 1970 and 1981. Now this particular copy has been taken out for the last time, by me. It is a grand gateway into Ovid, who was arguably the father of modern literature. This is the first of several blogs celebrating Ovid, this life-affirming poet, in this livingest of seasons--summer.

August 11, 2012

C Is for Contradiction in Hebron

Company C: An American's Life as a Citizen-Soldier in Israel by Haim Watzman

Company C: An American's Life as a Citizen-Soldier in Israel by Haim WatzmanMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Haim Watzman’s memoir of his years in reserve Company C of the Israeli infantry is a fine work of microscopy on the granulomatous sore of our modern-day Hundred Years War—the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With prose that’s both poetic and journalistically economical, Watzman chronicles the larger conflict by looking closely at the small patch of it he’s seen up close in his company and on his patrols. He gives the vivid sense of place and physical materials that characterizes the best narrative journalism (and the best accounts of Israel). Yet the book is less a war story than an Augustine-like self-inquiry. Watzman is a man of contradictions: an American emigrant to Israel trying to balance the “western humanism” of his secular background with the orthodox Judaism he adopted; a self-described klutz who’s also a fitness fanatic and rugged soldier; a soldier devoted to his reserve unit’s details in the occupied territories and a citizen opposed to the West Bank settlements.

The “West Bank” is itself a contradiction in terms—being that butterfly wing of land east of Israel proper, but so named for its position west of the Jordan River. There the Tomb of the Patriarchs lies, according to Judaeo-Christian tradition, amidst millions of modern Palestinian Arabs. This contradiction encysted in Israel’s left flank has inflamed a paradox inherent to democracy, which Winston Churchill famously described as the worst form of government except for all the others. It’s probably the sanest, most fair and rational form of government, but it’s also vulnerable to abuse by particularly loud, shrill, or demagogical voices, even when those voices are wayward and irrational minorities without their own respect for democracy. Governments like the old Mubarak regime in Egypt abjured democracy in part to resist such extremist influences. Israel, meanwhile, cannot seem to overrule its loudest and most doctrinaire voices, and history’s bad examples trail behind like buzzards—Periclean Athens, which devolved into the chaos of the Peloponnesian War, and the Roman Republic which devolved into that doomed, annoying empire. The poets fall silent shortly thereafter.

The American democracy feels a bit frayed by demagoguery in much the same way, but the stakes are always higher in Israel, which arose and remains in the mouth of its enemies. Furthermore, Israeli democracy bears the burden of sentiments particular to Jewish history. Lengthy exile as a persecuted minority has called us Jews together like a family. The Holocaust has excited an indwelling fear of extinction beyond any reasonable proportion. When I visited Israel in 1988, just after the first Intifada began, I heard the baying of the wolves outside the family circle and the answering call of my people. I felt the magnetism of Jerusalem’s stones, worn with ancient footsteps and impregnated with the blood and romance of the ages. For a Jew, there is no more romantic place on earth.

Israel’s founding father David ben Gurion told Shimon Peres that Israel was a family—and a family feeling of ‘us and them’ probably animates all patriotism on some level. Yet patriotism is a slippery slope to unsavory modes of civic being, to war with ‘enemies’ without, to oppression of minorities within, to rigid orthodoxies of who and how that directly contravene the core values of democracy. The settlements in the West Bank are absurd by most calculations, but Palestinian terrorism against innocents--and the many cases of unrepentant apologism for it among Palestinians--only inflames the patriotic paranoia and rigidity that sustains the occupation. Thus the Hundred Years War and one of history’s most painful granulomata.

View all my reviews

July 8, 2012

More on the Imperfect Science of the Heart

New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud

New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis by Sigmund FreudMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Every modern, educated person should read this book's predecessor, the (old) Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. For those interested in learning still more about psychoanalysis, the New Introductory Lectures are also vital. The latter work reflects clarifications in Freud's thinking since the original lectures given from 1915 to 1917 at the University of Vienna.

His daughter Anna Freud's book, The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense is also a very clear, very helpful and common sensical treatment of the subject of psychological defenses--i.e., the varieties of ways the mind lies to itself to protect itself from painful feelings and ideas.

There is at least one chapter in the New Introductory Lectures that is completely bizarre--Freud at his most cavalier and speculative, bordering on ridiculous--and it will do little to dispel the common canard that psychoanalysis is a "pseudo-science." It suffices to say that Freud wasn't perfect. But many great scientists make mistakes or fall prey to ideology; Einstein did (see this article, "The Master's Mistakes" from Discover Magazine); Linus Pauling, one of two people ever to win a Nobel prize in two different areas (Chemistry and Peace), had fairly lunatic ideas about vitamin C; and Isaac Newton wasted a lot of time in foolish speculations about alchemy. But we don't throw out what Einstein and Newton had right and we shouldn't throw out what Freud had right, which is about as revolutionary and beautiful as either of those physicists. Freud's works ought to be read like any other thinker's, not like orthodox readings of a Bible--that is, readers have no reason to try to retrofit reality to correspond with his scriptural errors--and just the same readers have no reason to dump the baby with the bathwater.

View all my reviews

June 19, 2012

Grendel

Grendel by John Gardner

Grendel by John GardnerMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

A brilliant, savage satire of existentialism and postmodernism. Gardner wrote against his times and hated other famous writers publicly (see for yourself here), and one ought to admire him for his iconoclasm. He was an uncommon man with real balls. To understand Grendel it's necessary to know of Gardner's disdain for what he called the "winking, mugging despair" of a writer like Thomas Pynchon. What a thing--to reimagine the monster Grendel, to imagine archetypal evil, as a sophomoric whinging nihilist philosophy major. Conversely, Gardner depicts Beowulf more or less without irony--he trusts in old notions of heroism as Yeats did and so Beowulf is the real deal, and the most heroic thing about him is that he means what he says and his words effect deeds in the real world on behalf of human dreams.

Grendel is funny and intermittently moving but it suffers from a certain coldness; there are limits to Gardner's sympathy for his protagonist, so we have a book like Madame Bovary about someone the author himself dislikes. The belated retelling of old myth--not modernist allusion but postmodern 'retelling'--reflects this compromise with the enemy. It becomes what it hates to a degree. Gardner's prose too is polished cold and smooth. We watch humanity from the uncivilized darkness with Grendel and appreciate the brilliance of the Shaper's words without being able to feel much of his joy.

View all my reviews

June 13, 2012

Lafcadio, the Lion Who Shot Back at Library Budget Cuts

Last Sunday morning a little before 9 o'clock, my wife and kids and I trooped up the front steps of the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza. As Hemingway would say, "It was hot." It was also so humid, the sun seemed to float in the air and it felt like you could have swum up the steps to the library. It's a beautiful Art Deco building that looks a little like the Superfriends' Hall of Justice. ("... Meanwhile, back at the Hall of Justice, Zan and Jana battle the budget cuts by turning into a lion and a rifle made of ice.")

Last Sunday morning a little before 9 o'clock, my wife and kids and I trooped up the front steps of the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza. As Hemingway would say, "It was hot." It was also so humid, the sun seemed to float in the air and it felt like you could have swum up the steps to the library. It's a beautiful Art Deco building that looks a little like the Superfriends' Hall of Justice. ("... Meanwhile, back at the Hall of Justice, Zan and Jana battle the budget cuts by turning into a lion and a rifle made of ice.") I was there for my 15-minute slot during the 24-Hour Read-In in support of the New York City public libraries. Sunday morning was devoted to kids' story time and for that reason, the organizer had judiciously asked that I refrain from showing up high or drunk and that I not read any porn. "Of course," I said, quickly shoving my crack pipe and latest issue of Hustler into my desk drawer. I told him how my elementary school librarian made me sit on the other side of the card catalog from the rest of the class for a month for talking, but that was the last time I had caused any trouble at a library.

I strolled around. A bronze screen, bearing bright gold figures from American literature, towered high above the front gate of the library. There were proof copies of kids' books available for free and I picked out some for my kids--and my older one actually started to read one of the books with great interest, and my younger one actually listened to the other readers reading kids' stories! At right is Babe the Blue Ox from the Legend of Paul Bunyan.

I strolled around. A bronze screen, bearing bright gold figures from American literature, towered high above the front gate of the library. There were proof copies of kids' books available for free and I picked out some for my kids--and my older one actually started to read one of the books with great interest, and my younger one actually listened to the other readers reading kids' stories! At right is Babe the Blue Ox from the Legend of Paul Bunyan. I chose to read from Lafcadio, the Lion Who Shot Back by Shel Silverstein. There were only five kids there, including my own, when I read, so you could say my 15-minutes were not exactly of fame--though I did have a microphone. When I introduced the book, I told the kids I wrote it. The story is about a young, naive lion who encounters a hunter and tries to make friends but is rebuffed. ('You don't have to shoot me to make me into a rug,' he says, 'I'll just lie on the floor.') The hunter says that's not very lionlike and prepares to shoot Lafcadio. Lafcadio decides to eat the hunter after all, takes his gun, practices with it, and when he runs out of ammo, he eats more hunters. He becomes a celebrity among the other lions and eventually a world-class sharpshooter. I looked up at this point and realized this was not a very "Park Slope" sort of story. I quickly reminded the parents of the kids that I didn't really write it,

that was just a joke. Lafcadio then joins the circus, becomes world-famous, develops the sort of ennui I imagine Shel Silverstein felt after too many parties at the Playboy Mansion, and goes back to the jungle, unsure whether he's a man or a lion. That is Natty Bumppo over there on the left.

that was just a joke. Lafcadio then joins the circus, becomes world-famous, develops the sort of ennui I imagine Shel Silverstein felt after too many parties at the Playboy Mansion, and goes back to the jungle, unsure whether he's a man or a lion. That is Natty Bumppo over there on the left.  There's no one quite like Shel Silverstein. He's hilarious and yet there's something literary and unfrivolous deep in the grain of his work, even his funniest and most joyous work--something faintly wounded, debauched, not quite settled, something prodding him forward a little ways across the normally observed boundaries. You can see it in the irisless eyes of his illustrations, those minuscule zeroes ellipsed with ellipses and unable to look back at you. There's an obstinately missing piece.... But that's part of what I love in the urbane, unsettled, honest, restless poetry and prose of Shel Silverstein.

There's no one quite like Shel Silverstein. He's hilarious and yet there's something literary and unfrivolous deep in the grain of his work, even his funniest and most joyous work--something faintly wounded, debauched, not quite settled, something prodding him forward a little ways across the normally observed boundaries. You can see it in the irisless eyes of his illustrations, those minuscule zeroes ellipsed with ellipses and unable to look back at you. There's an obstinately missing piece.... But that's part of what I love in the urbane, unsettled, honest, restless poetry and prose of Shel Silverstein. View all my reviews

May 29, 2012

King of Daydreams

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen KingMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Apparently, the entire Stephen King industry was spawned by a daydream about naked teenage girls in the shower, pelting another girl with tampons. And there's a great lesson in that: a creative writer can't censor himself--more than that, he has to pay close attention to his own imaginings and memories without shame, has to go beyond that and take those imaginings and memories seriously as the possible basis for an entire novel. Stephen King's slightly perverse little daydream turned out to be worth several hundred million dollars. Daydreams about naked girls: there's gold in them thar hills. But writers of every stripe, not only commercially oriented ones, should check this book out.

"I'm convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing," says Stephen King. True dat. A practical, unpretentious, useful guide to writing and a well-written, entertaining, sometimes moving memoir of the writing life all-in-one. It includes one of the best accounts around of a writer's imaginative process, illustrated with a fantastic case study of how King came up with the idea for his first novel, Carrie. (It involves aforementioned naked girls and tampons.)

View all my reviews

May 17, 2012

Epiphany in Dubliners

Dubliners: Text and Criticism by James Joyce

Dubliners: Text and Criticism by James JoyceDubliners was James Joyce's first book, and it's his most accessible, and possibly his most influential. The critic A. Walton Litz called Dubliners “a turning point in the development of English fiction.” Marc Wollaeger, editor of the Oxford Casebook on A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, writes that “Dubliners … virtually invented the modern short story.”

I don't know if Joyce invented the modern short story, but I can see pretty much everywhere in contemporary fiction the influence of Dubliners, of its Shakespearean / Chekhovian trope of self-discovery affixed with a technique of beautiful naturalistic symbolism--the blend of ancient artistic modes which Joyce called "epiphany." Joyce's writing style in Dubliners has more in common with Hemingway than it does with Virginia Woolf or William Faulkner (and Hemingway's best short stories clearly reflect Joyce's influence), but the characters in Dubliners are generally somewhat warmer and more vulnerable than Hemingway characters and Joyce depicts men and women with equal grace.

Brewster Ghiselin said in 1956 that the stories are organized according to the seven Christian virtues and the seven deadly sins, with each of the first fourteen stories assigned to a virtue or sin and the fifteenth story, the masterpiece "The Dead," thrown in for a delicious baker's dozen of tales of inner torment. I think it's obvious that Joyce did use that structure, though he turns vice and virtue on its head in the manner of Henrik Ibsen as he attacks the damaging institutions of psychological paralysis and self-mortification.

"The Sisters," the first story in this collection and the one that formally introduces the topic of psychological paralysis, is my personal favorite, but the two most famous stories, "Araby" and "The Dead," deserve all the praise they get.

I like the Viking Critical Library edition, at least the one that was published in 1976; the essays in the back are unusually helpful.

View all my reviews

Austin Ratner's Blog

- Austin Ratner's profile

- 32 followers