David Pilling's Blog, page 78

July 21, 2013

The White Hawk - Part Two!

Part II of The White Hawk, my Wars of the Roses saga, is now available.

It's a novella - about 40, 000 words - and so not as long as the first book: the historical events of the year 1469 that the story covers are very complex, with all manner of conspiracies and plots and counter-plots and rebellions, so I thought it best to divide the sequel into two sections. "Rebellion" covers the Battles of Edgecote and Lose-coat Field, and the endless machinations of the Earl of Warwick.

The Boltons are, of course, very much caught up in it all...read on to discover their fate!

The White Hawk (II): Rebellion

Published on July 21, 2013 12:28

July 18, 2013

Released!

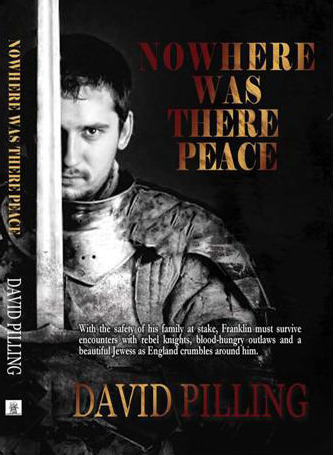

My latest novel, "Nowhere Was There Peace", has just been unleashed by the lovely folks at Fireship Press! The ebook is now available, and the paperback will follow in just a few days.

I love the cover (see above), a brooding image of a knight against a dark background: it really captures the mood of the story. Below is a summary of the plot:

"England, 1266 AD. Simon de Montfort is dead, butchered at the slaughter of Evesham, and England lies in ruins after years of civil war. Eager for revenge on his barons, King Henry III has disinherited all of de Montfort’s surviving followers.

The war is renewed as thousands of men are left with little choice but to snatch up their swords and fight to recover their stolen lands.

Hugh Franklin, a humble mason’s son from Southwark, is plunged into the eye of this storm when the Lord Edward, King Henry’s son and heir, recruits him as a government agent.

With the safety of his family at stake, Franklin must survive encounters with rebel knights, blood-hungry outlaws, and a beautiful Jewess as England crumbles in smoke and flame around him…"

Nowhere Was There Peace

Published on July 18, 2013 01:37

July 16, 2013

The Battle of Lewes, 1264

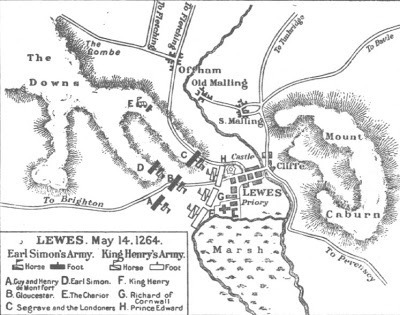

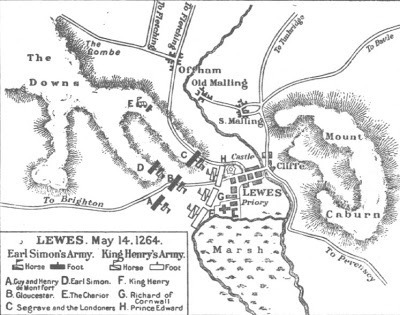

Today I'm going to talk about the famous Battle of Lewes, fought on the 14th of May 1264. The battle forms back of the backstory to my next book, Nowhere Was There Peace, shortly to be released by Fireship Press.

Much has been written about Lewes, but I want to concentrate on the fate of the unfortunate Londoners who supported Simon de Montfort against the army of King Henry III. Below is a rather good map of the battle and how it went down:

The causes of it are complex, but can be summarised thus: Henry III was something of an autocrat, and the favouritism he showed his wife's foreign relatives, refusal to compromise with his Barons and general political and military incompetence all came to a head in the 1260s. The French nobleman and Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, put himself at the head of a coalition of baronial rebels. After much argument and grave wagging of beards, both sides started to gather armies in the spring of 1264.

The seal of Simon de Montfort (c.1208-1265)

The seal of Simon de Montfort (c.1208-1265)

By May the King's forces had arrived at Lewes in Sussex, where they camped to allow time for reinforcements to join them. Henry based his troops near Saint Pancras Priory, while his eldest son, the hard-nosed Lord Edward, commanded a force of mounted knights and men-at-arms at Lewes Castle, to the north of his father's position.

There had been no wars in England since the reign of King John, Henry's father, and the preparations for the battle seem to have been pretty messy, with both sides gathering men where they could. De Montfort only had about five thousand men, about half the number of the royalists. His army was split into four divisions: one led by himself (though he had broken his leg in an accident and had to lead from the back in a litter), one by his son Henry, another by Gilbert de Clare, and the fourth by Nicholas de Segrave.

This last division consisted of what might be fairly described as a rabble of volunteers, ill-armed London citizens who had flocked to join de Montfort's army. The King and his family were particularly unpopular in London, thanks to the severe taxes Henry imposed on the citizens and the perceived tyranny of his Queen, Eleanor of Provence, and her foreign relatives. Some time prior to the battle, the citizens had expressed their dislike of Eleanor by pelting her barge with mud and stones as it floated down the Thames. Her son Edward had never forgotten the insult dealt to his mother, and waited impatiently for his chance of revenge. At Lewes he got it.

.

Tomb of Henry III

Tomb of Henry III

Knowing that he was outnumbered, de Montfort tried to avoid a battle by opening negotiations with the King, who refused them. De Montfort responded by making a sudden night march from his camp at Fletching to Offam Hill, just a mile from Lewes. The royalists were surprised by this maneuver, and even more surprised when de Montfort launched a surprise attack in the early hours of the morning, attacking and routing a group of royalist troops sent out to forage for supplies.

The royal army now heaved into life. Edward moved the quickest, and led his knights in a charge straight at Segrave's Londoners, still performing an excellent impression of a hopeless rabble. Unsurprisingly, they broke and ran like rabbits before the onrushing steel-clad monsters on enormous horses, and were slaughtered as they ran. The merciless pursuit continued for several miles - Edward had allowed his savage temper and desire for revenge to get the better of him, and had left his father's left flank exposed.

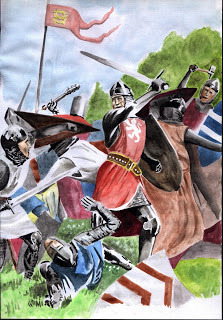

Royalists and rebels get stuck into each other at the Battle of Lewes

Royalists and rebels get stuck into each other at the Battle of Lewes

In the absence of Edward's cavalry, the King was obliged to order his centre and right flank to advance up Uffham hill and engage the baronial forces waiting for them. Many of the royalist soldiers had no experience of warfare, and had to endure an arrow-storm as they struggled up the slope towards a line of dismounted knights and men-at-arms, all bristling with various killing tools.

Neither the King or his brother, the Earl of Cornwall, possessed much in the way of military ability. Cornwall's division was the first to crumple, his men succumbing to panic shortly after the first blows were exchanged and streaming back down the hillside. Henry's men stubbornly fought on for a while longer, but broke when they were attacked in flank and rear by de Montfort's reserves.

By now, Edward had managed to regather his knights and lead them back to the battlefield. There they witnessed the royalists in full retreat back to the castle and priory, closely harried and pursued by the rebels. Edward was all for launching a death-or-glory counterattack, but first tracked down his father, who persuaded him that it was better to surrender and accept de Montfort's terms. His uncle, the luckless Cornwall, was found hiding in a windmill and dragged out to taunts of "Come out, come out, you wicked miller!"

The verdict of battle was reversed in the most emphatic fashion at Evesham, over a year later, but the slaughter of the Londoners at Lewes is significant to my tale. One young stonemason's son in particular manages to escape from the field, slung over the back of a packhorse and bleeding from wounds inflicted by the swords of Edward's knights. Who is he? Wait for the book to find out...

Much has been written about Lewes, but I want to concentrate on the fate of the unfortunate Londoners who supported Simon de Montfort against the army of King Henry III. Below is a rather good map of the battle and how it went down:

The causes of it are complex, but can be summarised thus: Henry III was something of an autocrat, and the favouritism he showed his wife's foreign relatives, refusal to compromise with his Barons and general political and military incompetence all came to a head in the 1260s. The French nobleman and Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort, put himself at the head of a coalition of baronial rebels. After much argument and grave wagging of beards, both sides started to gather armies in the spring of 1264.

The seal of Simon de Montfort (c.1208-1265)

The seal of Simon de Montfort (c.1208-1265)By May the King's forces had arrived at Lewes in Sussex, where they camped to allow time for reinforcements to join them. Henry based his troops near Saint Pancras Priory, while his eldest son, the hard-nosed Lord Edward, commanded a force of mounted knights and men-at-arms at Lewes Castle, to the north of his father's position.

There had been no wars in England since the reign of King John, Henry's father, and the preparations for the battle seem to have been pretty messy, with both sides gathering men where they could. De Montfort only had about five thousand men, about half the number of the royalists. His army was split into four divisions: one led by himself (though he had broken his leg in an accident and had to lead from the back in a litter), one by his son Henry, another by Gilbert de Clare, and the fourth by Nicholas de Segrave.

This last division consisted of what might be fairly described as a rabble of volunteers, ill-armed London citizens who had flocked to join de Montfort's army. The King and his family were particularly unpopular in London, thanks to the severe taxes Henry imposed on the citizens and the perceived tyranny of his Queen, Eleanor of Provence, and her foreign relatives. Some time prior to the battle, the citizens had expressed their dislike of Eleanor by pelting her barge with mud and stones as it floated down the Thames. Her son Edward had never forgotten the insult dealt to his mother, and waited impatiently for his chance of revenge. At Lewes he got it.

.

Tomb of Henry III

Tomb of Henry IIIKnowing that he was outnumbered, de Montfort tried to avoid a battle by opening negotiations with the King, who refused them. De Montfort responded by making a sudden night march from his camp at Fletching to Offam Hill, just a mile from Lewes. The royalists were surprised by this maneuver, and even more surprised when de Montfort launched a surprise attack in the early hours of the morning, attacking and routing a group of royalist troops sent out to forage for supplies.

The royal army now heaved into life. Edward moved the quickest, and led his knights in a charge straight at Segrave's Londoners, still performing an excellent impression of a hopeless rabble. Unsurprisingly, they broke and ran like rabbits before the onrushing steel-clad monsters on enormous horses, and were slaughtered as they ran. The merciless pursuit continued for several miles - Edward had allowed his savage temper and desire for revenge to get the better of him, and had left his father's left flank exposed.

Royalists and rebels get stuck into each other at the Battle of Lewes

Royalists and rebels get stuck into each other at the Battle of LewesIn the absence of Edward's cavalry, the King was obliged to order his centre and right flank to advance up Uffham hill and engage the baronial forces waiting for them. Many of the royalist soldiers had no experience of warfare, and had to endure an arrow-storm as they struggled up the slope towards a line of dismounted knights and men-at-arms, all bristling with various killing tools.

Neither the King or his brother, the Earl of Cornwall, possessed much in the way of military ability. Cornwall's division was the first to crumple, his men succumbing to panic shortly after the first blows were exchanged and streaming back down the hillside. Henry's men stubbornly fought on for a while longer, but broke when they were attacked in flank and rear by de Montfort's reserves.

By now, Edward had managed to regather his knights and lead them back to the battlefield. There they witnessed the royalists in full retreat back to the castle and priory, closely harried and pursued by the rebels. Edward was all for launching a death-or-glory counterattack, but first tracked down his father, who persuaded him that it was better to surrender and accept de Montfort's terms. His uncle, the luckless Cornwall, was found hiding in a windmill and dragged out to taunts of "Come out, come out, you wicked miller!"

The verdict of battle was reversed in the most emphatic fashion at Evesham, over a year later, but the slaughter of the Londoners at Lewes is significant to my tale. One young stonemason's son in particular manages to escape from the field, slung over the back of a packhorse and bleeding from wounds inflicted by the swords of Edward's knights. Who is he? Wait for the book to find out...

Published on July 16, 2013 07:50

July 7, 2013

A hiatus and a preview...

I will be away for the next fortnight or so doing some freelance work on behalf of the National Trust, so this blog will probably be very quiet for a while.

Just to (hopefully) whet a few reading appetites while I'm away, I will sign off with a sneak preview of my next book. It is called "Nowhere Was There Peace" - a quote taken from Walter Bower's 15th century chronicle of the history of the British Isles - and will be published very soon by Fireship Press. Below is the mean and moody cover, which I really like.

Fireship are an up and coming press, dedicated exclusively to publishing historical fiction. They have been fantastic to work with and you can check out their website at the link below:

Fireship Press

And here is the full quote from Bower's text, just to give a flavour of the story...

“Moreover all those who supported Simon in that battle were outlawed and disinherited. The greater part of the Disinherited infested the roads and streets and became robbers…a deadly struggle broke out between the king and the disinherited, in the course of which villages were burned, towns wrecked, whole stretches of land depopulated, churches pillaged, religious driven from their monasteries, clerics had money extorted from them and the common people were ruined. Nowhere was there peace, nowhere security.” Walter Bower, The Scotichronicon, p355

...and that's it, for now! Be back soon :)

Just to (hopefully) whet a few reading appetites while I'm away, I will sign off with a sneak preview of my next book. It is called "Nowhere Was There Peace" - a quote taken from Walter Bower's 15th century chronicle of the history of the British Isles - and will be published very soon by Fireship Press. Below is the mean and moody cover, which I really like.

Fireship are an up and coming press, dedicated exclusively to publishing historical fiction. They have been fantastic to work with and you can check out their website at the link below:

Fireship Press

And here is the full quote from Bower's text, just to give a flavour of the story...

“Moreover all those who supported Simon in that battle were outlawed and disinherited. The greater part of the Disinherited infested the roads and streets and became robbers…a deadly struggle broke out between the king and the disinherited, in the course of which villages were burned, towns wrecked, whole stretches of land depopulated, churches pillaged, religious driven from their monasteries, clerics had money extorted from them and the common people were ruined. Nowhere was there peace, nowhere security.” Walter Bower, The Scotichronicon, p355

...and that's it, for now! Be back soon :)

Published on July 07, 2013 02:44

July 1, 2013

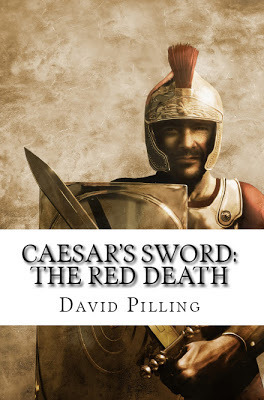

New covers...

"The White Hawk (I)" and "Caesar's Sword: The Red Death" have just acquired some smashing new covers...check 'em out!

Caesar's Sword on Amazon

The White Hawk (I) on Amazon

The White Hawk (I) on Amazon

Caesar's Sword on Amazon

The White Hawk (I) on Amazon

The White Hawk (I) on Amazon

Published on July 01, 2013 07:52

June 28, 2013

The Last Great General of Rome - Part One

"The Last Great General of Rome": that is how Lord Mahon, writing in 1829, described Flavius Belisarius. It is an inaccurate title, for the Roman Empire - or the Eastern half of it that endured until 1453 - produced many great soldiers and generals after the death of Belisarius, but he was the last to make any serious attempt to restore the power and glory of the Western Empire. He achieved a run of astonishing victories, all the more impressive since he was usually outnumbered and starved of resources by his envious and suspicious master, the Emperor Justinian I.

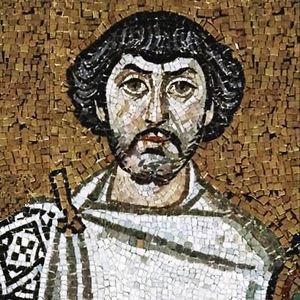

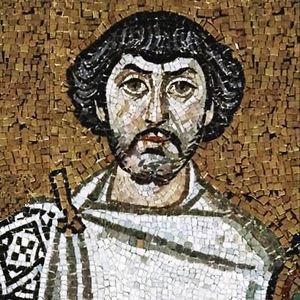

Possible depiction of Flavius Belisarius, from the Ravenna mosaics

Possible depiction of Flavius Belisarius, from the Ravenna mosaics

When I decided to write a novel set during the sixth century AD, between the fall of the Western Empire and the rise of Islam in the seventh century, the life and career of Belisarius immediately stood out. He has starred in fiction before, most notably in "Count Belisarius" by Robert Graves (author of "I, Claudius") but I very much wanted to draw my own version of him,

Born c.500 into a noble Illyrian or Thracian family in what is now south-west Bulgaria, little is known of Belisarius's early life. He joined the Roman army as a young man, and swiftly came to the attention of the aged Emperor Justin and his nephew, a clever, sharp-eyed little man named Justinian. Belisarius distinguished himself in the constant wars against the Sassanid Persians, who were chipping away at the shrunken Empire's Eastern frontiers. When Justin died and his nephew succeeded to the throne, Belisarius was made commander-in-chief of the Imperial armies in the East and sent to teach the Sassanids some manners.

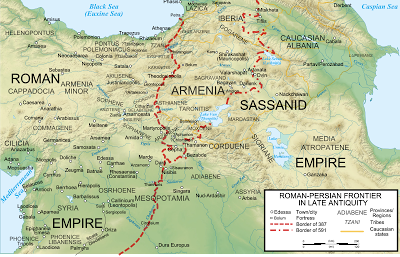

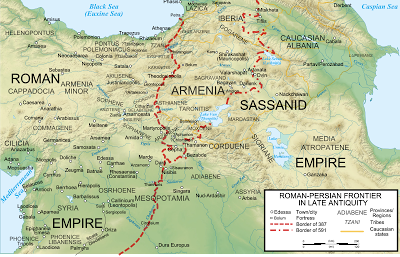

Map of the Roman-Persian frontier

Map of the Roman-Persian frontier

Belisarius proceeded to do just that, and at the Battle of Dara in 530 he routed a Persian army over twice the size of his own by using defensive tactics that he would repeat time and again: uncertain of the loyalty of many of his soldiers (by this time the famous Roman legions were long gone, and the 'Roman' army was largely made up of mercenaries), he dug a number of ditches and waited for the Persians to come to him. Charge after charge of cavalry was repelled, and when the enemy were exhausted Belisarius counter-attacked at the head of his best troops, the bucellari. The Persians were shattered and fled in rout, but Belisarius recalled the pursuit after a few miles. Wary that the Persians might rally and turn upon his unreliable soldiers, he allowed the majority of the beaten enemy host to escape.

A year later, at the Battle of Callinicum, Belisarius had cause to regret his hesitation. Reinforced by five thousand Lakhmid Arabs, the reformed Persian army attempted to invade Syria. Belisarius quickly moved against them, and by a series of brilliant maneuvers managed to block their advance. Puffed up by their success so far, his officers demanded the honour of fighting a pitched battle to round off the campaign. Belisarius didn't want to risk it, and attempted to persuade them otherwise. According to the historian Procopius, who accompanied the general on his many of campaigns, he spoke thus:

"Whither would you urge me? The most complete and happy victory is to baffle the force of an enemy without impairing our own, and in this favourable situation we are already placed. Is it not wiser to enjoy the advantages thus easily acquired, than to hazard them in the pursuit of more? Is it not enough to have altogether disappointed the arrogant hopes with which the Persians set out for this campaign, and compelled them to a speedy retreat?..."

Belisarius's eloquent pleas fell on deaf ears, and he found himself obliged to fight a battle at Callinicum, in northern Syria. For much of the day the result hung in the balance, but then a squadron of elite Persian cavalry stoved in the Roman right flank and sent their mercenary cavalry fleeing. The Roman army collapsed, and many soldiers drowned as they attempted to swim the Euphrates. Belisarius staged a fighting retreat. He dismounted and stood at the head of his infantry, forming an unbreakable line of shields against the Persian cavalry as they tried to follow up and complete their victory. As night fell, the Persians gave up and the remnant of the Roman army was able to withdraw in good order.

The Persian victory proved to be a Pyrrhic one. Though victorious, they had suffered terrible casualties and were unable to continue the invasion. Their commander, General Azarethes, was removed from command and stripped of his honours by the furious Persian Emperor. Weary of knocking each other about, both sides agreed to the Eternal Peace, a peace treaty that guaranteed cordial relations between the Roman Empire and Sassanid Persia forever: naturally, it was broken within a few years.

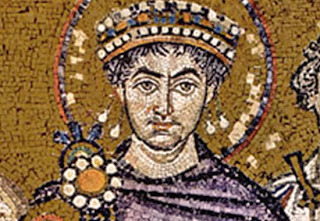

Emperor Justinian I

Emperor Justinian I

Despite his defeat at Callinicum, Belisarius had done well enough in his first Persian campaign to remain in favour with the Emperor. He was recalled to Constantinople, where he was the highest-ranking military officer on the spot when the 'Nika' riots broke out in 532 - the riots were started by the Blues and the Greens, the two major chariot racing factions in the city, and almost resulted in the destruction of Constantinople and the overthrow of Justinian. Belisarius had to move fast to rescue the situation...just how fast will be described in Part Two!

You can follow the adventures of Belisarius and his slightly less-than-devoted officer, Coel ap Amhar, in my novel "Caesar's Sword":

Caesar's Sword

Possible depiction of Flavius Belisarius, from the Ravenna mosaics

Possible depiction of Flavius Belisarius, from the Ravenna mosaics

When I decided to write a novel set during the sixth century AD, between the fall of the Western Empire and the rise of Islam in the seventh century, the life and career of Belisarius immediately stood out. He has starred in fiction before, most notably in "Count Belisarius" by Robert Graves (author of "I, Claudius") but I very much wanted to draw my own version of him,

Born c.500 into a noble Illyrian or Thracian family in what is now south-west Bulgaria, little is known of Belisarius's early life. He joined the Roman army as a young man, and swiftly came to the attention of the aged Emperor Justin and his nephew, a clever, sharp-eyed little man named Justinian. Belisarius distinguished himself in the constant wars against the Sassanid Persians, who were chipping away at the shrunken Empire's Eastern frontiers. When Justin died and his nephew succeeded to the throne, Belisarius was made commander-in-chief of the Imperial armies in the East and sent to teach the Sassanids some manners.

Map of the Roman-Persian frontier

Map of the Roman-Persian frontierBelisarius proceeded to do just that, and at the Battle of Dara in 530 he routed a Persian army over twice the size of his own by using defensive tactics that he would repeat time and again: uncertain of the loyalty of many of his soldiers (by this time the famous Roman legions were long gone, and the 'Roman' army was largely made up of mercenaries), he dug a number of ditches and waited for the Persians to come to him. Charge after charge of cavalry was repelled, and when the enemy were exhausted Belisarius counter-attacked at the head of his best troops, the bucellari. The Persians were shattered and fled in rout, but Belisarius recalled the pursuit after a few miles. Wary that the Persians might rally and turn upon his unreliable soldiers, he allowed the majority of the beaten enemy host to escape.

A year later, at the Battle of Callinicum, Belisarius had cause to regret his hesitation. Reinforced by five thousand Lakhmid Arabs, the reformed Persian army attempted to invade Syria. Belisarius quickly moved against them, and by a series of brilliant maneuvers managed to block their advance. Puffed up by their success so far, his officers demanded the honour of fighting a pitched battle to round off the campaign. Belisarius didn't want to risk it, and attempted to persuade them otherwise. According to the historian Procopius, who accompanied the general on his many of campaigns, he spoke thus:

"Whither would you urge me? The most complete and happy victory is to baffle the force of an enemy without impairing our own, and in this favourable situation we are already placed. Is it not wiser to enjoy the advantages thus easily acquired, than to hazard them in the pursuit of more? Is it not enough to have altogether disappointed the arrogant hopes with which the Persians set out for this campaign, and compelled them to a speedy retreat?..."

Belisarius's eloquent pleas fell on deaf ears, and he found himself obliged to fight a battle at Callinicum, in northern Syria. For much of the day the result hung in the balance, but then a squadron of elite Persian cavalry stoved in the Roman right flank and sent their mercenary cavalry fleeing. The Roman army collapsed, and many soldiers drowned as they attempted to swim the Euphrates. Belisarius staged a fighting retreat. He dismounted and stood at the head of his infantry, forming an unbreakable line of shields against the Persian cavalry as they tried to follow up and complete their victory. As night fell, the Persians gave up and the remnant of the Roman army was able to withdraw in good order.

The Persian victory proved to be a Pyrrhic one. Though victorious, they had suffered terrible casualties and were unable to continue the invasion. Their commander, General Azarethes, was removed from command and stripped of his honours by the furious Persian Emperor. Weary of knocking each other about, both sides agreed to the Eternal Peace, a peace treaty that guaranteed cordial relations between the Roman Empire and Sassanid Persia forever: naturally, it was broken within a few years.

Emperor Justinian I

Emperor Justinian I

Despite his defeat at Callinicum, Belisarius had done well enough in his first Persian campaign to remain in favour with the Emperor. He was recalled to Constantinople, where he was the highest-ranking military officer on the spot when the 'Nika' riots broke out in 532 - the riots were started by the Blues and the Greens, the two major chariot racing factions in the city, and almost resulted in the destruction of Constantinople and the overthrow of Justinian. Belisarius had to move fast to rescue the situation...just how fast will be described in Part Two!

You can follow the adventures of Belisarius and his slightly less-than-devoted officer, Coel ap Amhar, in my novel "Caesar's Sword":

Caesar's Sword

Published on June 28, 2013 03:05

June 27, 2013

Robyn Hode, part the Third

Part Three of my Robin Hood - or 'Robyn Hode' - series of short novellas is now available on Amazon. Readers of this blog might notice that I use a standard image for the covers, until my good friend and co-writer (as well as talented artist) Martin Bolton designs an individual cover for each installment.

The series has been going great guns so far, and I'm very pleased with the response. I thought I would share a customer review from Amazon, because it is very positive and the reader really 'got' what I am trying to achieve with the series:

"I have been an avid collector of books and films about Robin Hood for close to sixty years and believe that at some point I have probably read every book, fact or fiction about the legendary English hero, including juvenile fiction and some offerings that have been immediately consigned to the waste paper bin.

I bought Mr.Pilling's ROBYN HODE (1) in the belief that it was the first volume of a new series of novels. It is not, it is a short part work consisting of a handful of chapters, which I now understand will build into a full length saga over a period of time. This is my only disapointment with this publication... that I must wait between episodes for the next installment. This part followed on very quickly and I hope that the author will not keep us waiting too long until the next is released.

If the rest of the series in of the same quality or writing and style as this offering then they will build into one of the potentially best medieval fiction novels I have read in a long time, certainly on a par with Angus Donald's OUTLAW series.

The saga is set during the reign of Henry III, the most likely epoch for the source of the Robin Hood legends, and Mr. Pilling has choosen to base his tale not upon the commonly told legends of the Robin Hood ballads but around the snippets of historical records in the county rolls which may have some connection to the elusive outlaw hero; neatly stiched together with real historical characters interwoven to present a completely different vision of how the outlaw legend came to be with characters that are true to life with flaws and a dark side not just traditional villains and heros. This second enstallment fleshes out the characters of Gui of Gisburn, Tuck and the High Sheriff of Yorkshire and establishes Robyn as a denizen of the greenwood.

I now look forward to the next installments and hope that the promise of this developing into a really first class novel is met. My head tells me that I should wait to read the whole work but I know that in truth is shall not be able to resist taking in each part work as it is published. Meanwhile I will need to search out any other works that this author has to offer."

The series has been going great guns so far, and I'm very pleased with the response. I thought I would share a customer review from Amazon, because it is very positive and the reader really 'got' what I am trying to achieve with the series:

"I have been an avid collector of books and films about Robin Hood for close to sixty years and believe that at some point I have probably read every book, fact or fiction about the legendary English hero, including juvenile fiction and some offerings that have been immediately consigned to the waste paper bin.

I bought Mr.Pilling's ROBYN HODE (1) in the belief that it was the first volume of a new series of novels. It is not, it is a short part work consisting of a handful of chapters, which I now understand will build into a full length saga over a period of time. This is my only disapointment with this publication... that I must wait between episodes for the next installment. This part followed on very quickly and I hope that the author will not keep us waiting too long until the next is released.

If the rest of the series in of the same quality or writing and style as this offering then they will build into one of the potentially best medieval fiction novels I have read in a long time, certainly on a par with Angus Donald's OUTLAW series.

The saga is set during the reign of Henry III, the most likely epoch for the source of the Robin Hood legends, and Mr. Pilling has choosen to base his tale not upon the commonly told legends of the Robin Hood ballads but around the snippets of historical records in the county rolls which may have some connection to the elusive outlaw hero; neatly stiched together with real historical characters interwoven to present a completely different vision of how the outlaw legend came to be with characters that are true to life with flaws and a dark side not just traditional villains and heros. This second enstallment fleshes out the characters of Gui of Gisburn, Tuck and the High Sheriff of Yorkshire and establishes Robyn as a denizen of the greenwood.

I now look forward to the next installments and hope that the promise of this developing into a really first class novel is met. My head tells me that I should wait to read the whole work but I know that in truth is shall not be able to resist taking in each part work as it is published. Meanwhile I will need to search out any other works that this author has to offer."

Published on June 27, 2013 01:56

June 19, 2013

Chariots!

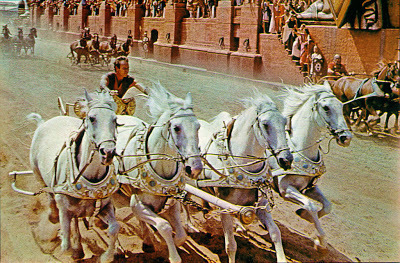

Many of us will have seen Charlton Heston giving it some whip in the chariot race in 'Ben Hur', or more recently, Russell Crowe dishing out orders and lopping off heads in the race sequence in 'Gladiator'. When I was planning my novel set in the Late Roman Empire, I wanted to try and capture the pulse-pounding excitement of chariot racing, Roman-style, on the page.

The novel, "Caesar's Sword", is set mostly in Constantinople of the early 6th century AD, during the reign of the Emperor Justinian I. By this time most of the blood-spattered public games that the Roman public had been addicted to for centuries were banned, forbidden by the Christian church, who regarded them as savage pagan entertainments and a pointless waste of life.

One sport, however, the church dared not try to ban, and that was chariot racing. The 'Romans' of Constantinople - they still called themselves Romans at this point, rather than the later Byzantines - were feverishly addicted to the races, and avidly followed the fortunes of the competing teams - much as football and basketball (etc) fans do today.

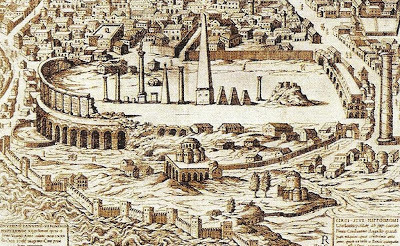

Old illustration of the ruined Hippodrome in Istanbul (Constantinople)

Old illustration of the ruined Hippodrome in Istanbul (Constantinople)The races were originally transported from Rome and consisted of four teams: the Blues, the Greens, the Reds and the Whites. By Justinian's reign only the Blues and the Greens still enjoyed considerable followings. The population of the city was sharply divided in their loyalties between these two teams, to the extent that violent clashes in the streets between gangs of rival supporters were common (sound familiar?).

Often the violence escalated into widespread looting and general disorder, and the Emperor was obliged to send his guards out to restore order. However, the passion for the races affected all classes, and sometimes the Emperor himself gained or lost popularity thanks to his support for one or the other team. Justinian, for instance, was known to favour the Greens, and as a result was deeply unpopular with the Blue section of the city. His unpopularity was one of the reasons for the 'Nika' riots that erupted in the city in the early years of Justinian's reign, and which also feature in my novel.

The races were staged inside the Hippodrome, a gigantic U-shaped structure next to the imperial palace, and which served as Constantinople's version of the famous Circus Maximus in Rome. There was a lodge in the centre of the arena for the Emperor and his entourage to watch the races, and also to hear complaints from representatives of the Greens and the Blues: the Hippodrome was as much a government building as a sporting venue, and a complex warren of governments departments and offices existed beneath it.

In the finest Roman tradition, the races themselves were violent and bloody affairs, and the death and serious injury of charioteers was common. The chariots were lightweight affairs usually pulled by teams of four horses, and the drivers were allowed to strike at each other with their whips, or even force their opponents into the 'Spina', a row of statues and monuments in the centre of the track. Forcing another driver to crash, injuring or even killing himself and his horses in the process, was considered a great trick.

Emperor Justinian I and his court

Emperor Justinian I and his courtAs if that wasn't enough, Roman citizens used to enter the arena with bags of heavy lead amulets covered in spikes and engraved with the names of drivers they particularly hated. During races they would throw the amulets at the object of their passion, hoping to smash his skull (for this reason, drivers wore helmets) or at least distract him enough to veer off the track. Romans also created wax dolls - like voodoo dolls - of unpopular drivers and stuck nails and pins into them before a race, hoping they would meet with bad fortune.

By the time of my story, Constantinople was sports-mad, and the contending passions of the Blue and Green faction was beginning to infect every aspect of city life and government. The atmosphere inside the city was volatile. Thrown into the melting pot were high taxes, an unpopular Emperor and a not very successful war in the East against the Sassanid Persians. The imperial city was ready to blow, and just needed one match to light the explosion...

Caesar's Sword

Published on June 19, 2013 06:52

June 12, 2013

Arthur's (other) children

King Arthur and Sir Mordred duel to the death at Camlann

King Arthur and Sir Mordred duel to the death at CamlannMany with a passing knowledge of the Arthurian legend will be aware that Arthur is finally betrayed and killed by his own son, Sir Mordred, at the Battle of Camlann, thus closing the circle of treachery and incest that began when Arthur's father, Uther Pendragon, betrayed Duke Gorlois and slept with his wife Igraine (it's a cheerful tale).

Mordred is usually portrayed in modern versions of the legend as Arthur's only son, the product of an unfortunate one-night stand with his own half-sister, Morgana. Dig a little deeper into other versions of the legend, and you will find that Arthur sired many more children. One of them, the strangely-named Sir Borre le Cure Hardy, appears briefly in Malory's La Morte D'Arthur as the result of another of Arthur's illicit unions, this time with an earl's daughter named Sanam. The horny young monarch 'had ado with her', apparently, and the result was Borre. He grew to be a 'good knight', but not so good as to be mentioned more than twice in the whole of Malory's very long tale.

The 'Twrch Trwyth', a savage and gigantic boar hunted by Arthur's warriors

The 'Twrch Trwyth', a savage and gigantic boar hunted by Arthur's warriorsSwitching to the Welsh tales, we find that Arthur has three sons: Gwydre, Amhar and Llacheu. All three come to sticky ends. Gwydre is slaughtered by the monstrous wild boar, the 'Twrch Trwyth', along with two of Arthur's maternal uncles. Llacheu is killed at the Battle of Llongborth, as recounted by the following stanza (translated from the Welsh):

"I was there where Llacheu fell,Arthur's son renowned in song,When ravens flocked on the gore..."

In later legend Llacheu appears as Sir Loholt, and is treacherously slain by the envious Sir Kay.

Amhar is possibly the most interesting of the three, for he is slain by none other than Arthur, his own father. Nennius says the following in the Historia Brittonum (written c.800AD):

“There is another wonder in the country called Ergyng. There is a tomb there by a spring, called Llygad Amhar; the name of the man buried in the tomb was Amhar. He was the son of the warrior Arthur, who killed him there and buried him.”

Incredibly, no explanation is given why Arthur killed his own son. Fertile ground for fiction here, and from this seed was born the idea for my latest book, "Caesar's Sword." I provide my own explanation for Amhar's death, as described by his son and Arthur's grandson, Coel.

Coel has an extremely hard time of it. After the tragedy of Camlann he and his mother are forced to flee to the Continent, and from hence to Constantinople and the Eastern Empire...

I should say a big 'thank you' to Tyler Tichelaar for his fantastic book, "King Arthur's Children", which provides lots of eye-opening information about the tangled history of Arthur and his offpsring through the ages.

Published on June 12, 2013 02:10

June 10, 2013

Blog Hop winner's announcement!

...and the winner of the Summer Banquet Blog Hop iiisssss.....

TINNEY HEATH!

Well done, Tinney :) And a big thank you to everyone else who entered, read my post and 'hopped' with the best of them!

A free paperback copy of The White Hawk will be winging its way to the winner ASAP!

More hops will surely follow, so keep your eyes peeled....

TINNEY HEATH!

Well done, Tinney :) And a big thank you to everyone else who entered, read my post and 'hopped' with the best of them!

A free paperback copy of The White Hawk will be winging its way to the winner ASAP!

More hops will surely follow, so keep your eyes peeled....

Published on June 10, 2013 02:16