Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 59

March 6, 2024

Over 900 pages

March 5, 2024

AMAZING SCULPTURES AND COLLAGES BY A BRITISH POP ARTIST

HUMOUR, IMAGINATION, PLAYFULNESS, wit, social criticism, and creativity – these are all words that can be applied to the works of the artist Peter Blake, which are on show in a superb exhibition at the Waddington Custot gallery in London’s Cork Street until the 13th of April 2024.

Blake was born in 1932 in Dartford (Kent). He studied art at Gravesend Technical College, and then at the Royal College of Art in Kensington. He is a leading British exponent of Pop Art, which, according to Wikipedia:

“… is an art movement that emerged in the United Kingdom and the United States during the mid- to late-1950s.The movement presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including imagery from popular and mass culture, such as advertising, comic books and mundane mass-produced objects. One of its aims is to use images of popular culture in art, emphasizing the banal or kitschy elements of any culture, most often through the use of irony.”

One of Blake’s most familiar works is the album sleeve for the Beatle’s LP “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”, which he designed along with Jann Haworth, his wife between 1963 and 1979. I wonder how many Beatle’s fans know that Blake was involved with making the image on this.

The exhibition at Waddington Custot is dedicated to Blake’s sculptural works. There has not been one during the last 20 years. Although there are many of his sculptures in the gallery’s three interconnecting rooms, many of his ingeniously witty collages are also on display. Employing images from comics, old books, and other printed matter, these collages are so carefully assembled that unless one looks at them closely and extremely obliquely, it is difficult to realise that these artefacts are not prints but collages.

The sculptures are with only a very few exceptions, wonderful assemblages or tableaux constructed with found objects. For example, one of these is a shelf overloaded with miniature booze bottles, all positioned beneath a miniature image of Leonardo da Vinci’s depiction of the Last Supper. There are several model sailing boats, on which Blake has placed plastic models (toys) of people expressing a range of behaviours. Other sculptural assemblies are more complex and need to be seen rather than described. I mentioned ‘exceptions’ at the beginning of this paragraph. This refers to four objects – they look like large stones (one of which is a carved stone head) – which Blake called “Found Sculpture”. Each of these is mounted on its own plinth. By doing so, the artist has ‘elevated’ these natural objects to the status of ‘fine art’, and as the gallery’s hand-out said, they challenge:

“… conventional notions of artistic materials …”

I loved the exhibition. Every exhibit is both interesting and beautiful … and great fun. As the show’s hand-out correctly stated, Blake’s sculptures are:

“… by turns quirky, endearing or engaged with conceptual concerns.”

His creations:

“… offer starting points for imagined narratives, each with a glimmer of Blake’s typically gentle, English sense of humour.”

And this is quite correct. Skilfully conceived and executed, Blake’s works provide nourishment for both the eye and brain in a delightfully digestible form. If you view the exhibition with an open state of mind, you are bound to gain great enjoyment from it.

March 4, 2024

Some things never seem to change

DURING THE 1970s and 1980s, we used to make visits to a restaurant in north London’s Willesden Lane. Founded in 1964 and specialising in South Indian cuisine, it was called Vijay. It still exists at the same address. Out of curiosity and ‘for old times’ sake’, we paid it a visit last night (the 29th of February 2024).

Entering Vijay was like stepping back in time. It was uncanny; nothing seemed to have changed. The walls are still lined with raffia work panelling, the wooden Kerala-style ceiling, and the pictures on the wall (mostly colourful depictions of Hindu deities) looked exactly as we remembered. Naturally, none of the staff were recognizable.

Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, we used to eat at Vijay to enjoy South Indian dishes that were not easy to find elsewhere in London. If I remember correctly, in those days Vijay only had this kind of food on its menu. Today, the menu still has South Indian dishes, but also many offerings of food that is definitely not typical of South India. It offers a wide selection of North Indian dishes – such as most British people would hope to find in an ‘Indian restaurant’. One of the hors d’oeuvres, which you would never find on India, but is common in British Indian restaurants is fried pappads (poppadums) served with a tray of chutneys and pickles to accompany them, Vijay now offers this. Probably, Vijay has added North Indian dishes to their menu because, for many potential customers, South Indian dishes are far less familiar.

Yesterday, we ordered a few dishes. They were enjoyable enough but not outstanding, However, it was great fun sitting in a place that had hardly changed since we last visited it at least 30 years ago.

March 3, 2024

WOMEN AS DEPICTED BOTH BY A MAN AND BY THEMSELVES AT TATE BRITAIN

I DO NOT KNOW whether it was deliberate or accidental that currently (until the 7th of April 2024) there are two contrasting (or, maybe, complementary) exhibitions on in the galleries of London’s Tate Britain.

On the first floor, there is an exhibition called “Sargent and Fashion”. It is a collection of paintings by the American-born artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who was born in Florence (Italy) and died in London (UK). The aim of the show is, according to the Tate’s website, to show:

“… how this remarkable painter used fashion to create portraits of the time, which still captivate today.”

The exhibition includes some of Sargent’s portraits alongside a few of the items of clothing that his subjects wore whilst he was creating their portraits. In this well laid out show, the viewer gets to see that Sargent was an excellent painter, whose portraits manage to radiate the natures of the sitters’ personalities. I doubt that most of Sargent’s subjects would have been disappointed with the pictures he produced for them. Many of the paintings are portraits of women. Almost all of them were depicted wearing elegant clothes, and are superbly executed conventional portraits. They celebrate aspects of the ‘respectable’ (i.e., wealthy) society of his times.

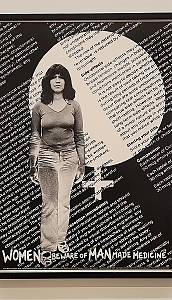

Beneath the Sargent exhibition, on the ground floor of Tate Britain, there is an exhibition showing how women in Britain broke out of their conventional male-dominated lifestyle during the 1970s and 1980s. Called “WOMEN IN REVOLT Art, Activism and the Women’s movement in the UK 1970–1990”, it is according to the Tate’s website, it is:

“… a wide-ranging exploration of feminist art by over 100 women artists working in the UK. It shines a spotlight on how networks of women used radical ideas and rebellious methods to make an invaluable contribution to British culture. Their art helped fuel the women’s liberation movement during a period of significant social, economic and political change.”

During a long part of the period covered by the show, Britain had its first female Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher (in office from 1979-1990). Although she fought her way through hitherto male bastions to emerge as the country’s first lady Prime Minister and showed what women were capable of doing in the world of politics, she was not a feminist icon, as Natasha Walter wrote in The Guardian (online 5th of January 2012):

“Obviously Thatcher was no feminist: she had no interest in social equality, she knew nothing of female solidarity … We should never forget her destructive policies or sanitise her corrosive legacy. But nor should we deny the fact that as the outsider who pushed her way inside, as the woman in a man’s world, she was a towering rebuke to those who believe women are unsuited to the pursuit and enjoyment of power. Girls who grew up when she was running the country were able to imagine leadership as a female quality in a way that girls today struggle to do. And for that reason she is still a figure that feminists would be unwise to dismiss.”

However, as Baroness Burt of Solihull said in the House of Lords on the 5th of February 2018:

“… my next figure is 1979, which, of course, was the date when we got our first female Prime Minister. Personally, I would feel more inclined to celebrate this milestone if she had encouraged other women to come forward, to use some of the talented women that she had at her disposal. But, sadly, she got to the top and pulled the ladder up behind her, which is a great shame, because the whole point of having representation from all parts of society is to make for better government.”

As several exhibits on display at the Tate (until the show ends on the 7th of April 2024), Mrs Thatcher was intensely disliked by artists encouraging ‘female liberation’.

Before entering the exhibition, I was a little worried that all I would see was propaganda and other polemic material. Well, there was plenty of that kind of thing, and much of it was both interesting and often visually intriguing – sometimes quite witty. The exhibition, which is excellently curated, also includes many paintings, sculptures, videos, and other artistic items. These have mostly been created by female artists with whom I am not familiar. And all of them are both visually engaging and satisfying. Several of these were of Indian heritage, and others have ‘black’ African heritage. There are also cases containing printed material that propagated feminist ideas. Included amongst these were a few copies of the magazine Spare Rib, which I remember seeing at friends’ houses many years ago. My future wife was one its readers. Published between 1973 and 1993, its aim was to challenge the traditional roles of females (of all ages) and to explore new ways in which they could engage in society. In fact, this was the aim of many – if not all – of the works in the exhibition.

We visited both exhibitions today (the 28th of February 2024), to experience the contrast between them. Both are excellent in their own ways and achieve what the curators intended. They are both well worth visiting. However, to my taste, the exhibition on the ground floor was far more exhilarating and inspiring, that the more conventional show on the floor above it.

March 2, 2024

WHERE ONCE THERE WAS A PUB IN HAMPSTEAD THERE IS NOW A SUPERMARKET

HAMPSTEAD IS RICH in historical curiosities. One of them is an unexceptional little road that has an interesting story.

Just south of Tesco’s supermarket (the former Express Dairy) on Hampstead’s Heath Street there is a narrow cul-de-sac called Yorkshire Grey Place. It enters Heath Street across the road from The Horseshoe pub and Oriel Place. I have often wondered about this short, uninviting blind-ended lane and its history. Just under 50 yards in length, it runs west from Heath Street.

At long last, I began looking on the Internet for some history (if any) of this bleak little roadway lined on both sides with high buildings. It gets its name from a pub that used to exist near it – The Yorkshire Grey. The pub was already in existence by 1723, but was demolished in the 1880s (https://londonwiki.co.uk/Middlesex/Hampstead/YorkshireGrey.shtml) – in 1886, according to FE Baines in his “Records of Hampstead” (publ. 1890). An online history of Hampstead (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol9/pp15-33) provided the following information about the pub and its surroundings:

“North of Church Row the Yorkshire Grey had been built by 1723 and cottages called Evans Row probably faced it c. 1730. In 1757 the inn and 14 houses occupied by a brickmaker, clockmaker, carpenter, apothecary, and others were ‘late freehold’ but in 1762 they were described as copyhold (one alehouse, two houses, and 11 cottages).”

This area was one of the slums of Hampstead – it was devoid of water supply and drainage.

During the planning and construction of Fitzjohns Avenue, which began in 1875 and was only completed by about 1887, there was some discussion about whether it should end on the High Street or give direct access to the road up to Hampstead Heath. Prior to the late 1880s, the recently built Avenue stopped south of Hampstead village. Its route from there into the centre of Hampstead village was subject to some controversy. This was described in “Hampstead, Building a Borough 1650-1964” by FML Thomson, as follows:

“… The shopkeepers in the High Street feared loss of trade if any traffic was diverted to a new route, and held out for a scheme which would debouch Fitzjohn’s Avenue into High Street at the King William IV ; while the gentry wanted the direct route to Heath Street and the Heath, arguing that this gave a bit of slum clearance of Bradley’s Buildings, Yorkshire Grey Yard, and Bakers’ Row as a bonus. The dissension continued when the scheme was revived with a number of public meetings in 1881, dominated by the gentry element which was increasingly exasperated at having its carriages bottled up in Fitzjohn’s Avenue without any proper exit.”

As it turned out, the “gentry element” had their way, and the slum clearance that affected Yorkshire Grey Yard was carried out – the pub disappeared as a result. In relation to this, the online history of Hampstead, already quoted revealed:

“In 1883 the Metropolitan Street Improvement Act authorized redevelopment of the whole area at the joint expense of the local authority and M.B.W. In 1888 High Street was widened, Fitzjohn’s Avenue (then Greenhill Road) was extended to meet Heath Street, and soon afterwards Crockett’s Court, Bradley’s Buildings, and other slums, including Oriel House and other tenemented houses, were replaced by Oriel Place, shops, and tenement blocks.”

The pub has long gone, but I managed to find two pictures depicting it. One is a painting showing the place in about 1863 (https://artuk.org/discover/artists/lester-harry). It was the work of Harry Lester. The other is a black and white photograph in the book by FE Baines, which was published a year after the pub was demolished. A detailed map surveyed in 1868 showed that the pub was quite a large building with a substantial yard next to its east facing façade. To its west, the yard opened on Little Church Row (now part of Heath Street). This and a blind-ending road called Yorkshire Grey Yard are shown on the map. Immediately south of the pub, there was another cul-de-sac running from east to west – it was unnamed. I believe that this is what is now called Yorkshire Grey Place.

The map drawn in 1868 shows the layout of the area around today’s branch of Tescos before Fitzjohn’s Avenue was conceived. Another map drawn in 1915 shows how the topography of the area changed following the completion of the Avenue. The Yorkshire Grey pub existed before the nearby, still existing, Horseshoe pub was established – it appears on the 1915 map. Originally named ‘The Three Horseshoes’, it moved from Hampstead High Street to its present address in 1890. Had the Yorkshire Grey pub survived, it would have been about 110 feet away from the Horseshoe.

Once again, wondering what is in a name – in this case Yorkshire Grey Place – has opened my eyes to an interesting bit of the history of Hampstead. Finally, it is interesting to note that the Victorian building that houses Tesco’s was built in 1889 – three years after the Yorkshire Grey pub was demolished to make way for buildings along the northern continuation of Fitzjohns Avenue. So, next time you are queuing to pay in Hampstead’s Tesco, remember that you are standing on land where once the patrons of the Yorkshire Grey once trod.

You can read much more about Hampstead and its surroundings in my book, which is available from Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/BENEATH-WIDE-SKY-HAMPSTEAD-ENVIRONS/dp/B09R2WRK92/

March 1, 2024

An oil painting hanging on a wall in a café in Hampstead

EVERY TIME I VISIT Hampstead, I feel pleasant twinges of nostalgia not only because I was brought up in the area but also because of my associations with the place after childhood. One place, which still exists, and has done so since it first opened in 1963, is Louis Patisserie on Heath Street. Originally, its shop sign bore the words “Louis Hungarian Patisserie” because it had been established by a Hungarian called Louis Permayer.

Sometime in 1970 or maybe the following year, I took a young lady, who is now my wife, to Hampstead on our ‘first date’. We had a genteel afternoon rendezvous at Louis. My wife remembers that she had coffee, and that it had been served with a separate bowl containing freshly whipped cream. Back in those days and for many years afterwards, Louis, with its wood-panelled walls, seemed to me to have a ‘touch of class’ as well as being evocative of Central Europe. The cakes and other baked items they used to sell were all good quality versions of what you might expect to find in a ‘Konditorei’ in Vienna or a ‘Cukrászda’ in Budapest.

Today (the 26th of February 2024), it was windy and extremely cold when we got off the bus in Hampstead. For old time’s sake, we entered Louis to warm up with hot beverages. Louis has long since changed hands, but the wood-panelling and several other original features still remain. However neither the hot beverages nor the patisserie items were of the same high quality as they used to be long ago. There are now other places in Hampstead where both the coffee and the food are superior to what is available at Louis, but none of these places bring back happy memories.

High on the end wall of the sitting area within Louis, there is a large, framed painting of a pond with buildings along one side of it. These are reflected in the water. In the foreground, three figures are depicted fishing with rods. The picture is painted with muted colours, or, possibly, the colours have faded since it was completed. Despite having visited Louis on numerous occasions, I had never looked at the painting properly until today. At the lower left corner of the painting, there is the artist’s name and a date:

“DC Towner 1972”

The artist was the painter and ceramics expert Donald Chisholm Towner (1903-1985). For many years, he was a resident of Hampstead, as this biography ( www.barnebys.co.uk/auctions/lot/donald-chisholm-towner-SrpyTddupt ) explains:

“… Towner was born at Eastbourne and studied at Eastbourne and Brighton schools of art and at the Royal College of Art under William Rothenstein 1923-1927. He moved to Hampstead in 1927 where he lived until his death and produced many paintings of the area and residents. D.C. Towner showed at the RA, Burgh House, NEAC etc.”

William Rothenstein (1872-1945), mentioned above, lived in Hampstead between 1902 and 1912, but by the time he taught Towner he was living elsewhere. It is unlikely that Towner lived in Hampstead because of Rothenstein. It was more likely that he chose the area because it was already favoured by many other artists.

Although DC Towner is not one of the greatest of the artists who lived and worked in Hampstead, his family name has related to the arts in another way – possibly better known than for his paintings. When his father, Alderman John Chisholm Towner of Eastbourne, died in 1920, he left 22 paintings and £6000 for the establishment of a public art gallery. Rehoused in a new gallery opened in 2009, the Towner Gallery still exists in Eastbourne. We visited it in its beautifully designed new home in 2019.

As the picture in Louis was painted in 1972, we would not have seen it on our ‘first date’. I do not know when it was purchased or acquired by the owner of the café. Who knows, but maybe the artist used to enjoy ‘Kaffee und Kuchen’ in the place where I took my future wife out one afternoon long ago.

PS: If you wish to see another of Towner’s paintings in Hampstead, you should visit the Lady Chapel of St John’s Parish Church in Church Row. In it, you can see Towner’s depiction of Church Row, where he lived, and his self-portrait – he used a mirror image of his own face for the Christ in this painting. The picture in the church was created to commemorate the artist’s mother, Grace Towner (1862-1949), who lived in Church Row and was buried nearby in St John’s cemetery.

February 29, 2024

THE ONLY REMAINING VISUAL EVIDENCE OF A CREEK IN WEST LONDON

IN MY BOOK about west London, “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London”, I described a stream that used to flow through Hammersmith. It was located where part of Furnivall Gardens now stands today. I wrote:

“… Furnivall Gardens, a pleasant open space created in 1951, and named after a distinguished scholar of English literature and an important pioneer in the sport of rowing, Dr Frederick James Furnivall (1825-1910) … Before WW2, the area of the park was covered with industrial buildings including the Phoenix Lead Mills, which stood east of The Creek, an inlet of the Thames that was filled-in in 1936.

In earlier times, The Creek, which extended as far inland as today’s King Street, was centre of Hammersmith’s flourishing fishing industry. Writing in 1876, James Thorne described The Creek as follows: ‘… a dirty little inlet of the Thames, which is crossed by a wooden footbridge, built originally by Bishop Sherlock in 1751 … the region of squalid tenements bordering the Creek having acquired the cognomen of Little Wapping, probably from its confined and dirty character.’

The Creek, an outlet of the now largely hidden Stamford Brook, is long gone, but there is a storm outlet in the bank of the Thames close to where The Creek emptied into the river. This can be seen from Dove Pier at the western end of the Gardens.”

Today, the 25th of February 2024, we were walking past Furnivall Gardens along the riverside path. It was low tide. A wide, not too clean, beach lined the river. At one point, the beach was interrupted by what looked like the mouth of a small stream. This was lined on both sides with wooden fencing. The stream, which issued from below the riverside walkway ended abruptly in an archway that was filled by a sturdy door or dam. The position of this sluice gate in relation to the nearby Dove pub, Dove Pier, and Furnivall Gardens is correct for what must have once been the mouth of Hammersmith’s erstwhile Creek. I had noticed the archway with the heavy-looking door many times before, but today, because of the low tide, it was the first time that I could clearly the remnants of the mouth of the Creek. I suppose that there is some leakage from the now covered-up Creek that causes the appearance of the mouth of a small stream when the tide is out.

My illustrated book about West London is available as a paperback and a Kindle from:

February 28, 2024

Entangled messaging at an exhibition at London’s Royal Academy

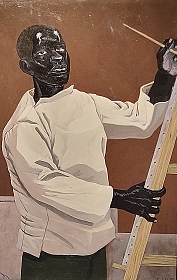

I LEAVE SOME EXHIBITIONS feeling both inspired and exhilarated. Some other displays of art neither thrill nor depress me. However, the current show at the Royal Academy of Art (‘RA’) in London’s Piccadilly – “Entangled Pasts 1768 – now” – left me feeling both disappointed and a little irritated. Before proceeding further, I should explain that 1768 was the year in which the RA was founded. The exhibition is, to quote its associated handout, to explore:

“… connections between art associated with the Royal Academy and Britain’s colonial histories.”

It does this by mixing artworks by academicians with those by other artists in a series of mostly poorly lit, gloomy galleries. Each of the rooms is supposed to contain works that are connected with a particular theme, although I found that the linkage between the artworks and the theme within each gallery was weak to say the least.

The sad thing is that many of the exhibits on display are interesting works of art, but seeing them altogether reminded me of visiting a poorly organised jumble sale. Although the works in each room were supposed to be thematically linked, that was hard to realise by looking at them as a group. The overarching concept of the exhibition was to, yet again, remind us of Britain’s unsavoury history of relations with ‘people of colour’. Consequently, many exhibits were ones that had been exhibited before in shows with similar messaging. One gallery managed to combine the unpleasant history of Britain’s involvement with the slave trade with another topical subject – climate change. This is probably because there are many who link colonialisation with industrialisation and its effects on climate.

Although I am presenting you with a negative view of the exhibition, I should in all fairness point out a couple of things I loved. One was an installation consisting of models of ships suspended from the ceiling by fine threads. This visually exciting work was created by Hew Locke, and was in one of the few rooms that was brightly lit. The other exhibit, which occupied two galleries was a collection of painted wooden cut-outs depicting people at a carnival. This work, which was accompanied by a soundtrack with voice and music, was created by Lubaina Hamid – like Locke a Royal Academician – in 2004. I was also interested to see the original painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray by David Martin (1737-1797), who was a Royal Academician. These two ladies were associated with Kenwood House in north London, where a photograph of the painting is on display. It was nice to see the original. There were other artworks I liked in the exhibition, but felt that their impact was spoiled by being displayed alongside other works without much evidence of thoughtful curating.

I felt that “Entangled Pasts” was yet another ‘blockbuster’ show designed to earn income, which is greatly needed in the present difficult economic climate. This exhibition exploits the race card to attract visitors, which it appears to be doing. Just in case I have not discouraged you from seeing the show, you should know that it ends on the 28th of April 2024.

February 27, 2024

An old inn

February 26, 2024

Bushy eyebrows running in the family

PEOPLE WHO HAVE met me often remark on my bushy eyebrows. Barbers are always keen to trim them, but I will not let them do that.

Many years ago, sometime in the 1980s if I remember correctly, my father and I were invited to a birthday party to celebrate the 70th birthday of my Dad’s step-brother Frank Walt. It was a large gathering held in a house in London’s St Johns Wood. Apart from my father, there was nobody at the occasion, whom I had met before. While I was wandering about rather aimlessly, a small lady came up to me, and declared in a North American accent:

“You must be a Halperin. You have the Halperin look.”

At that time, I had no idea what she meant by this. Even though I had no clue about what she was talking about, what she said made me feel good – I felt it was special to be recognised as part of a ‘clan’ by someone who did not know me ‘from Adam’, as the saying goes.

I now know about the Halperin family. Put simply, my father’s mother was Leah (née Halperin). She was one of the six children of Joseph and Deborah Halperin. A few days ago (in February 2024), a cousin sent me a photograph of Leah’s brother Wolf Halperin. I looked at it, and immediately realised what my fellow guest at Frank’s party had meant by the ‘Halperin look’. Wearing a Fedora hat, Wolf’s eyebrows immediately reminded me of mine and those of other members of the Yamey family. Seeing this was uncanny.

Wolf Halperin died many years ago, long before I began visiting India. Last November (i.e., 2023), we visited a small shop in Baroda (Gujarat). It was not our first visit. We had been there once about 5 years earlier. The shopkeeper recognised us immediately. As he said (in Gujarati) “I remember you”, he pointed at my eyebrows.