Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 61

February 14, 2024

Subversion at the Serpentine art gallery: ways with words

THE ORIGINAL SERPENTINE Gallery in London’s Kensington Gardens is housed in a former tea pavilion that was built in 1934. It began to be used as a contemporary art exhibition space in 1970. Since then, it has been showing modern and contemporary artworks in a series of temporary exhibitions. I have been visiting this gallery and its newer branch, Serpentine North, regularly since the 1990s (the North branch opened in 2013). Almost without exception, the art displayed in the Serpentine galleries has been both exciting and adventurous – sometimes quite challenging. The latest exhibition, which is on until the 17th of March 2024 in the original gallery, is of artworks by the American (USA) artist Barbara Kruger, who was born in Newark (NJ) in 1945.

Kruger’s art is not purely visual. It is designed to convey ideas that challenge the viewer to question commonly held contemporary beliefs in an eye-catching, often witty way. The exhibition, “Thinking of You. I mean Me. I mean You” consists of 12 art installations that reference or parody everyday things such as advertising, magazine illustration, video art, social media, the Internet, and other media that bombard us on a daily basis. Each of them present messages that subvert political ideas, the moral code, and the meanings of words. Kruger makes much use of video techniques. Several of the exhibits have words projected sequentially to make up sentences. Often, the words change on the screen to alter the perceived meaning of the text being projected. However, her art is not simply all about words and their meanings in different textual environments. The words are harmoniously accompanied by intriguing visual images, often continuously changing.

Although the exhibition is about words and their usage and varying meanings, words alone cannot describe this exhibition adequately. Therefore, if you can, it is worth taking a look at this interesting – nay, challenging – show. Having viewed the show, I was heartened to discover this artist from America who is perceptive enough to see where her country is heading and brave enough to criticise the political direction in which it appears to be moving. After seeing her exhibition, I would hazard a guess that she will not be voting for Mr Trump.

February 13, 2024

Five and a half hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT): India

INDIA IS A very large country. At its greatest width, it spans almost 1800 miles from east (the Manipur/Bangladesh border) to the west (the western edge of Kutch where it borders Pakistan.). When it is 4 am (GMT) in London, 1500 miles away in Moscow (Russia) and 1800 miles away in Ankara (Turkey), it is 7 am. Yet, when the sun rises at 4 am in the far east of India, people in Kutch (western Gujarat) will not see the sun rise until 5.30 am. In both places, the clock will show ‘4 am’. This difference arises because all of India (as well as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka) are in the same time zone (Indian Standard Time: ‘IST’). IST is five and a half hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (‘GMT’). Incidentally, while researching this piece, I noticed that clocks in Nepal are 5 ¾ hours ahead of GMT.

Some countries spanning many degrees of longitude such as India does, are divided into several time zones (e.g. the USA, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Russia). However, all of India is in a single time zone, I wondered why and whose idea it was in the first place.

Prior to the colonisation of India by the British, various methods of standardising time were adopted in different eras and under varying ruling regimes. For example, in the 4th century BC, the prime meridian was chosen as a line passing through what is now the modern town of Ujjain (in Madhya Pradesh) and the unit of time was based on the ‘prana’ (about 4 seconds – the length of a normal breath).

In 1802, John Goldingham, the official astronomer of the British East India Company, established Madras Time, which was 5 hours, 21 minutes and 14 seconds ahead of GMT. In 1884, Calcutta Standard Time was established. This was 5 hours, 53 minutes and 20 seconds ahead of GMT. It remained in use until 1948 despite other changes in time zoning having already occurred in India. At the same time as Calcutta Standard Time was created, Bombay Standard Time also came into existence – it was 4 hours and 51 minutes ahead of GMT. Although it no longer exists, it is still used in Parsi fire temples in Bombay.

Madras Time was used by the railways in British India until the 1st of January 1906, when IST came into existence. It was then that the geographical reference point for time standardisation was moved from Madras to Shankargarh Fort in the district of Allahabad. The reference meridian chosen, 82 degrees and 30 seconds East, was deemed to be the midpoint of India, as it was under British rule. In 1947, when India became independent, IST was kept as the country’s official time. However, both Calcutta Time and Bombay Time remained in use until 1948 and 1955 respectively. The idea of splitting India into two time zones has been mooted, but has yet to happen.

Although IST is the official time in all parts of India, an interesting variation is still in use in the tea gardens in the far east of the country (www.timeanddate.com/time/zone/india). Called ‘Chai Bagan Time (Tea Garden Time), it is one hour ahead of IST (and 6 ½ hours ahead of GMT). It was introduced by British tea companies to increase the number of daylight hours available for working, and is still in use. Using this timing, the sun rises at 5 in the morning instead of at 4 (IST) and sets at about 6 in the evening instead of 5 (IST).

Bombay Time has all but disappeared from use. However, it has been replaced by what some call ‘Bombay timing’, which refers to the habit of people to arrive incredibly late for appointments – especially social engagements. Finally, in a book about Bangalore by Peter Colaco, there is mention of yet another measure of time. There is ‘fie-mint’, which does not mean ‘five minutes’, but does mean ‘not very soon’. For example, he wrote:

“A waiter in a restaurant, once told me our order would take ‘fie-mint’. Did he mean a ‘five minute ‘fie-mint’ or a 30-minute ‘fie-mint’, I asked. He considered the question seriously. ‘Twenty-mint fie-mint’, he clarified.”

February 12, 2024

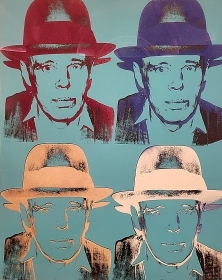

Repetitions of an image need not necessarily be monotonous

IF I WERE to tell you that I have just seen an exhibition of well over fifty photographic portraits of one person, all reproduced from the same original print, and enjoyed it, you might begin to wonder about me and my sense of aesthetics. Well, I really did enjoy this exhibition at the Thaddeus Ropac gallery in London’s Mayfair. If you wish to share the experience, you will have to hurry, because the show ends on the 9th of February 2024.

On or soon after the 30th of October 1979, the German artist and political activist (e.g., a co-founder of the German Green Party) Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), who was in New York City for the installation of a retrospective exhibition of his works at the Guggenheim Museum, was taken to meet the American Pop artist Andy Warhol (1928-1987). During that encounter, Warhol used his Polaroid camera to make a portrait of Beuys wearing his characteristic felt hat. It was not the first time that Warhol had photographed Beuys. He had also used his Polaroid when he first met Beuys earlier in 1979 at the Hans Mayer gallery in Düsseldorf (Germany). This meeting has been recorded on film (see https://youtu.be/PRrC8EJ3KxI?si=DM4RoR9nDrX_cJbX).

Between 1980 and 1986, Warhol used his Polaroid photograph of Beuys as the source image for a series of screen-printed portraits. As the Press Release on the website of the Thaddeus Ropac Gallery explained:

“Repeating Beuys’s arresting gaze on different scales and in different formats, Warhol exercised his characteristically experimental approach to materials in the portraits. Amongst the paintings, unique Trial Proofs, line drawings, and unique and editioned works on paper, are examples of some of the artist’s earliest uses of diamond dust in portraits. These sit alongside images that have had their tonal values inverted to give the effect of photographic negatives. Belonging to the Reversal Series in which Warhol reproduced key subjects from across his wide-reaching body of work – including his iconic portraits of Marilyn Monroe, the Mona Lisa and Mao …”

In the 1940s, Warhol began his working life in commercial and advertising art. By the 1950s, he had discovered the secret of repeating images making small changes to produce variations on a theme. In 1952, he had his first solo exhibition in an art gallery (in NYC). Although it was not well received, it was not long before he became recognised as an artist of note. In 1962, he learned screen-printing techniques, and became one of the first artists to use this process for creating artworks. These include most of the images on display at Thaddeus Ropac.

The results, which we were able to see at the gallery were far from monotonous, despite being repetitions of the same photograph. By modifying the sizes, colouration, and many other aspects of the photographic portrait, Warhol managed to bring a considerable degree of liveliness to this image. As I saw the various diverse presentations of the single image of Beuys, the German artist began to feel oddly familiar. It was almost as if I was meeting an old friend.

Before seeing the exhibition, I had my doubts about viewing what I had heard were multiple reproductions of the same photograph. My worries were dispelled within a few seconds of looking at the exhibition. I was fascinated how one image could be altered in so many different ways and the effect that seeing the results had on me, There are now less than 24 hours left before the show ends. So, if you can, hurry up and view it.

February 11, 2024

Ceramic creation

February 10, 2024

An accident in a crowded street in Calcutta

SOME YEARS AGO (in 1997), we attended the first performance at London’s Nehru Centre (in Mayfair) of a work, “Samaveda Opus 2”, by the composer John Taverner (1944-2013). Taverner introduced the piece. During his introduction he repeated the sentence “India wounds me” several times. I have no idea what he meant by this, but the words have stuck in my mind. Until our latest visit to Calcutta (Kolkata), which was in January 2024, India has never wounded us. However, one morning, an unfortunate incident occurred, which I will now describe.

We (my wife Lopa and I) decided that we would revisit the 18th century Armenian church of St Bortola, which is in Bara Bazar in North Calcutta. Before leaving the Tollygunge Club, where we were staying, we found out from a website on the Internet that the church was supposed to be open. After enjoying good coffee at Blue Tokay in Bahrison’s bookshop on Park Street, we hailed a yellow and black Ambassador cab. The driver knew where we wanted to go and drove us through ever increasingly congested streets to Netaji Subhas Road in Bara Bazar. In this crowded street, the traffic was so bad that vehicles could barely move. As we were quite near to St Bortola, we disembarked, having decided to walk the rest of the way. As it happened, the narrow side streets along which we wended our way were so full of people that it would have been almost impossible for a taxi to go along them.

Busy bazaars always fascinate me. The streets in the part of Bara Bazaar near to the church were no exception. As we walked along them, we realised that we were in a district that was home to the shops and stores of merchants who sold chemicals in wholesale quantities. After negotiating the crowds in a couple of lanes, we spotted to spire of St Bortola, towering above the chaotic ensemble of buildings below it. We found the entrance to the compound containing the church. There were several men, including some security personnel, sitting in the porch. They all were very sure that visitors were not allowed to visit the church, nor even to photograph it. We protested that the website had claimed it would be open. We were told that if we wanted to view the church, we would first have to get special permission from the Armenian College (which is close to Park Street).

Having failed to gain access to the Armenian Church, we decided to visit the nearby Roman Catholic cathedral – The Cathedral of the Most Holy Rosary on Brabourne Road, almost opposite the Magen David Synagogue. Brabourne Road is one of the main thoroughfares carrying traffic to and from the Howrah Bridge, which crosses the Hooghly River. To say that this road as extremely busy is an understatement. Lined with stalls, the pavements are almost un-negotiable. So, pedestrians, including us walk along the edges of the roadway. People walk in both directions, often carrying heavy loads – usually on their heads. Added to this, many people seem to be in a great hurry and think nothing of rudely pushing aside fellow pedestrians. Meanwhile, buses, cars, wagons, rickshaws, heavy trucks, bicycles, motorbikes, and a variety of other wheeled vehicles rush past the pedestrians on the street. We experienced all this on a hot mid-morning.

We had to cross Brabourne Road to reach the cathedral. Fortunately, most of the traffic came to a stop briefly at a red traffic signal, and we joined a crowd of people swarming across the road. We began negotiating the crowds in an attempt to reach the cathedral. Then, it happened.

A wagon loaded with filled white sacks approached us. The sacks projected beyond the sides of the wagon. There were so many people walking along the side of the road that it was impossible for us to get out of the way of this heavily laden vehicle. Suddenly, one of the sacks hit Lopa’s shoulder, and she was sent flying. I was horrified. Luckily, she was thrown away from the road and her fall was cushioned by soft goods on the flimsy trestle tables of some pavement vendors. Although very shocked and extremely upset, she escaped major injury. Fortunately, her only injury was a small graze on her hand. She had had a lucky escape.

Much to my surprise, after a few minutes, Lopa decided we should walk the short distance to the cathedral. This we managed without any further unfortunate incidences. The compound – a peaceful garden in front of the west end of the church was open. However, when we reached the church, it was locked up. Someone sitting on the porch informed us that it was only opened once a week – on Sundays, and only for one mass.

By now, we had had our fill of Bara Bazaar. We hailed an Ambassador taxi to take us back to the Tollygunge Club. When Lopa related her unfortunate incident to the driver, he told us that Bara bazar is a bad area filled with ‘badmashs’ (i.e., bad or unprincipled people).

This unfortunate accident in Bara Bazaar was, as far as I can recall, the first time (in 30 years) that India wounded us. Having said that, I am sure it was not a physical injury that led John Taverner to say “India wounds me”.

February 9, 2024

Eradicating the ego: the art of Masaomi Yasunaga

DURING OUR TRIP to India in late 2023 and early 2024, we saw works of art that have been created using ceramics. The creators of these ceramic artworks shape clay into a form that they have in mind, glaze it, and fire the object in a kiln. The artists hope that what emerges from the kiln after firing and cooling will resemble what they had in mind. The resulting sculptures and other artworks bear the conceptual imprints of the artists’ visions – usually with considerable accuracy.

Today, the 7th of February 2024, we visited an exhibition in London’s Lisson Gallery in Paddington. On until the 10th of February 2024, it is a display of the creations of the Japanese sculptor Masaomi Yasunaga (born 1982), who works in Japan. All the exhibits are bizarre but beautiful – quite unlike anything I have ever seen.

Yasunaga is part of an avant-garde group of Japanese artists, Sodeisha, which was formed after WW2. The movement rejected and challenged previous Japanese artistic traditions. It also introduced non-functional ceramic objects as an artform. The objects on display at the Lisson Gallery were created as follows. Yasunaga used glaze rather than clay as his starting material. Combining it with raw materials such as feldspar, whole rocks, metal and glass powders, he created artistic forms. Then, he buried the creations in layers of sand and kaolin, before subjecting the whole lot to heat in a high temperature kiln. After the firing and cooling, the sculptures were carefully excavated from the beds (of kaolin and sand) in which they were fired.

Apart from fusing the various elements of each artwork, the heat of the furnace also produces unexpected transformations (both chemical and morphological) of the work so that although it bears some resemblance to what existed before firing, it has acquired characteristics that the artist would not have been able to foretell. The action of the fire in destroying the artist’s original conception is described by Yasunaga as follows:

“…melting the material and letting gravity take hold of its shape once again, eradicating the ego along the way …”

Further, he explained:

“… the ultimate goal of my art is not self-expression but what’s left of self, after being filtered through fire.”

The effects of the heat are uncontrollable, but as the website of the Lisson Gallery explained:

“… Yasunaga describes how beauty can be discovered in the most uncontrollable situations, referring to the process of his sculptures transitioning in the fire, evolving from something artificial to natural, and yielding a beauty that is perfectly pure.”

Regardless of how and why these sculptures have been created, they are a joy to behold. One of the many roles of an artist is to show us the world in a new light and to open our minds to new ideas. Yasunaga has achieved both aims in a wonderful way.

February 7, 2024

A building with a strangely shaped roof in London’s Kensington

Here is a brief excerpt from my illustrated book “BEYOND MARYLEBONE AND MAYFAIR: EXPLORING WEST LONDON”. It concerns a curiously shaped building constructed in the early 1960s in Kensington:

“Returning to High Street Kensington, the eastern wall of the Melbury Court block of flats bears a plaque commemorating the cartoonist Anthony Low (1891-1963), who lived in flat number 33. Set back from the main road, and partly hidden by two hideous cuboid buildings, stands an unusual glass-clad building with an amazing, distorted tent-shaped roof made of copper. This used to be the Commonwealth Institute. Built in 1962 (architects: Robert Matthew Johnson-Marshall & Partners), I remember, as a schoolboy, visiting the rather gloomy collection of ethnographic exhibits that it contained shortly after it opened.

The Institute closed in late 2002, and the fascinating building stood empty until 2012, when it was restored and re-modelled internally. In 2016, it became the home of the Design Museum. Like the architecturally spectacular Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, the building competes with the exhibits for the viewer’s attention but wins over them easily. The displays in the Design Museum are a poor advert for the great skills of British designers, whereas the building’s restored interior is a triumph. This is a place to enjoy the building rather than the exhibits. One notable exception to this comment is the sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), which stands outside the front of the museum.”

You can discover much more about Kensington and many places west of it by reading my book, which is available (as a paperback and a Kindle) from Amazon:

RELICS OF A GREAT INDIAN WRITER AT A LIBRARY IN CALCUTTA

THE CALCUTTA CLUB (in Kolkata) was founded in 1907. Unlike other ‘elite’ clubs in existence at that time, it admitted members regardless of their ethnic background. The Club has a library consisting of several rooms arranged in a line, each one connecting to the next. At the far end of the library, there is a locked door bearing the label:

“Nirad C Chaudhuri Corner”.

Nirad Chaudhuri was one of 20th century India’s great writers. Born in 1897 at Kishoreganj – a place that is now in Bangladesh, but was then in British East Bengal – he died in Oxford (UK), having passed his 101st birthday. He was an original thinker whose views have not been shared by everyone. He wrote about India and its history in an incisive way that was not fettered by the conventional ideas of his contemporaries. In the 1970s, he shifted from India to England, and settled in Oxford. A few years ago, we met and were befriended by his son Prithvi – now a physically and intellectually active octogenarian. When we are staying at the Tollygunge Club (in south Kolkata), we often meet him after breakfast to chat and enjoy cups of coffee.

During one of our morning meetings, he told us how his father’s books and other possessions were shipped to India after his demise. He mentioned that some of these things are now stored in a room at the library of the Calcutta Club in what has been called the ‘Nirad Chaudhuri Corner’. As we expressed interest in seeing this, he said that he would ring the relevant Calcutta Club committee member to arrange for us to view his father’s collection. Although the Club feel they were given the items, Prithvi said that he had simply lent them. The matter is currently being contested in court. He told us that although there is much to see at the Calcutta Club, some of his father’s collection – notably his collection of books written in French – have been stored elsewhere.

The following day, we visited the Club’s library, where a librarian showed us to, and then unlocked, the Nirad Chaudhuri Corner. Apart from books that belonged to Nirad, there are paintings and other objects. One of these is the Royal Proclamation that was written when he was awarded the honour of the Commander of the British Empire (‘CBE’) in 1992. There are also several objets d’art including decorative ceramics (plates and cups), an ancient Egyptian sculpture, some wine glasses, a bottle of vintage port, a set of the first UK metric currency coins to have been issued, and many other things. The paintings include a well-executed hand-painted copy of a picture by Monet – a famous French impressionist. Prithvi told us that when his father bought the painting, he paid a great deal of money for it. Some of the family disapproved, but as Prithvi rightly said, it was his own money.

After examining the Corner, we walked back through the library. On the way, I spotted a small, framed manuscript. It was labelled “Original Signature of Mr Satyajit Ray Membership No. R211”. For those who do not know, Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), born in Bengal, was one of India’s most famous film directors.

Thanks to Prithvi, we were able to see a fascinating collection of possessions once owned by a great Indian writer. Almost hidden in the Calcutta Club’s library, I doubt that many of its members have seen it or are even aware of its existence.

February 6, 2024

A watchful waterfowl on te Serpentine in Hyde Park

February 5, 2024

An advantage of wearing a hijab in an airport in a Gulf State

THINGS DID NOT BEGIN well for me when I arrived at Bangalore Airport’s recently opened Terminal 2 prior to boarding an Emirates airline flight to Dubai, where we were to catch another flight to London. We arrived at the airport in good time – before the check-in desks were open. After finding somewhere to sit, I walked to the Chaayos refreshment stall and asked for two cups of south Indian filter coffee. The server must have misheard me and only charged me for one. When this arrived instead of the two, I was expecting, I paid for another cup. While it was being made, I carried the first to my wife. I returned to the stall and picked up the second cup. It was filled to the brim, very hot, and the cup was poorly insulated. Just before I reached where we were sitting, my hand moved slightly, and the boiling hot coffee fell on my palm. This was extremely painful. I dropped the cup and the rest of its contents. I rushed to the washrooms, and after finding a tap that worked, I rinsed my palm in cold water. Meanwhile, my wife managed to get me some ice to put on the scalded part of my hand.

Dubai Airport

Dubai Airport After dropping off our baggage and collecting boarding passes (printed on extremely thin paper), we headed for the security check. This involves divesting oneself of anything that contains metal before walking through a metal-detecting arch and then being frisked by a security official. Because the trousers I was wearing were too big, I had to keep one hand on them to stop them falling down. Meanwhile, I was somewhat shocked, and my hand was still smarting after the scalding.

After the frisking, I went over to the conveyor belt that carried our hand baggage and other items slowly through an x-ray machine. After rescuing both my wife’s and my own cabin baggage, telephones, wallets, coats, neck cushion, and my trouser belt, I secured my trousers with the latter. It was then that I realised that my boarding pass was nowhere to be seen. I was horrified – in so many decades of flying, I had never lost a boarding pass.

We reported the loss to the security supervisor – a female officer. She rang for an official from Emirates airline. While waiting for him to arrive, she said to my wife in Hindustani:

“He should not worry. They won’t leave him behind.”

After an agonising wait – actually, it was no longer than about 15 minutes – the official arrived. By then, I was feeling both anxious and extremely upset. The Emirates man explained that I would be issued a new boarding pass at the boarding gate. Not entirely happy with that, we left the security area, and headed for the departure lounges. On the way, we came across an empty baggage trolley, and began loading it with our carry-on bags and coats. As we were doing that, something fell to the ground – it was my missing boarding pass. In an instant my mood of melancholy and apprehension switched to one of immense happiness and relief. I rushed back to the security supervisor to tell her the good news. As the Emirates man was still around, I told him and shook his hand.

The flight to Dubai was pleasant. There was nothing to complain about. At Dubai, we had to pass through another security check. This time, I decided not to remove my belt before passing through the metal detector. Instead, I untucked my shirt and covered my belt with it. Despite there being a large metal buckle on the belt, the detector did not detect it. Nobody stopped me. Meanwhile, passengers’ hand baggage was passing through an x-ray machine so quickly that I doubt there was time to examine the series of x-ray images in any detail – if at all.

After enjoying exorbitantly expensive hot drinks, which I did not manage to spill, we entered a departure lounge dedicated to our flight to London. Before entering the lounge’s seating area, an official examined each passenger’s passport and boarding pass. Most passengers, including my wife and I, had to head for a line of trestle tables. By each of them there was a male or female security official. A few passengers were sent straight into the seating area, bypassing the tables.

The officials standing at the tables first searched the contents of bags – rather cursorily. Then, using an electronic wand, they frisked the passenger. After that, each passenger was asked to present their hands, palms facing upwards. An explosives detector sponge was rubbed on each palm, on the clothing, within the footwear (which had to be removed), on the mobile ‘phones, and other carry-on items. After placing the (re-usable) sponges in a machine, we were allowed to sit down and await the flight. My wife told me that the security lady who examined her was both rude and rough.

This process took quite a while. I sat watching it and gradually, I and my wife became aware of something curious. About a third of the passengers on our flight were women wearing hijabs (Muslim head coverings). This was not surprising in an airport in a Gulf State. What was astonishing was that not one of them had to be searched at the tables. They were allowed to board the flight without having been checked as thoroughly as the other passengers had been. Given that very recently, soldiers wearing hijab were able to enter a hospital in Gaza and attack it with firearms, was it wise to assume that because they were wearing hijab, the passengers on our flight to London were beyond suspicion, whereas all the other passengers – both male and female – needed to be regarded as potential terrorists?

The flight to London could not be faulted. And in case you are wondering, by the time we landed at Heathrow, my scalded palm was neither painful nor inflamed.