Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 55

April 13, 2024

A colourful tunnel with paintings beneath Waterloo Station

LEAKE STREET RUNS beneath the platforms and tracks of London’s Waterloo Station. It is 300 yards long and its walls and ceiling are covered with colourful graffiti created with cans of paint spray. The artwork creation in this street that runs in a tunnel was inaugurated in May 2008 during the Cans Festival, which was organised by the artist known as Banksy.

Unlike many public places in London, painting the walls in Leake Street is legal. Walking along this highly decorated street is a magnificent experience, which you can repeat often because the images on the wall are frequently changed. If you are lucky, you can watch the artists in action.

April 12, 2024

Walking beneath the waters of the River Thames

IT IS NOT NECESSARY to be able to hold your breath for a long time or to carry a snorkel or even air cylinders to be able to stroll leisurely deep below the surface of London’s River Thames. If you fancy a walk beneath the water, the Greenwich Foot Tunnel is the place to be. It can be entered by stairs or using a wood panel-lined lift from one of its two entrances – the southern one near the Cutty Sark in Greenwich, and the northern one at Island Gardens.

The tunnel, which is circular in cross-section, is 405 yards in length, and 50 feet beneath the river at its deepest point. For most of its length it is 3 yards (9 feet) in diameter, and it slopes downwards at both ends. Its construction began in 1899 and was completed in 1902. Therefore, building the tunnel happened during the entire time that the 2nd Anglo-Boer War was being fought in South Africa. The lifts that are housed beneath domed structures at each end of the tunnel were ready for use in 1904. Judging by the appearance of the wood panelling within the lift carriages, it looks as if these were installed many years ago. Despite their vintage appearance the lifts have been modernised and work without needing an operator.

Although there many notices forbidding cycling in the tunnel, there is no shortage of cyclists disobeying this rule. This makes walking in the tunnel slightly hazardous as the cyclists speed along the narrow walkway in the long, straight tunnel. Using the tunnel is a convenient way of traversing the Thames and gives one the opportunity to walk under water.

April 11, 2024

An artist baptised

Inside St Bartholomew the Great, London

In this stone font

Was William Hogarth baptised

Artist of great fame

April 10, 2024

Sell the wife at Smithfield instead of divorcing her

IF YOU WISH to see the meat market at London’s Smithfield in action, either you must go to bed very late or wake up quite early, because the market is only open between 2 am and 10 am. This April, we visited it at about 1.30 in the afternoon, and there was little to see and there was hardly any odour in the air.

Back in October 2017, I walked from Clerkenwell to Smithfield, and wrote about it in a blog I published (https://londonadam.travellerspoint.com/44/). Here is what I wrote about the meat market:

“At Peters Lane, Cowcross street turns southward towards to meet St Johns Street, which commences at the north side of Smithfield Market, an indoor wholesale meat marketplace. Smithfield’s central Grand Avenue is entered through an archway flanked by two heraldic dragons and a pair of stone sculptures. The Avenue runs beneath a high roof supported by ornate painted ironwork arches. Side aisles are lined with the meat dealers’ stalls and glass-covered display cabinets. In 1852, London’s livestock market was moved from Smithfield to Copenhagen Fields in Islington (off Caledonian Road, where the Caledonian Park is now located). This cleared the area for the construction of the present meat market, which was completed by 1868. Constructed in an era before refrigerators were used, the market was designed to keep out the sun and to take advantages of prevailing breezes.”

I continued as follows:

“In mediaeval times, Smithfield had a bad reputation. It was known for criminal activity, violence, and public executions. In the early 19th century, when obtaining divorce was difficult, men brought their unwanted wives to Smithfield to sell them, then a legal way of ending a marriage (see: “Meat, Commerce and the City: The London Food Market, 1800–1855”, by RS Metcalfe, publ. 2015).”

In relation to disposing of a spouse, I quoted the following verse by an unknown author quoted in “Modern Street Ballads”, by John Ashton (published 1888):

“He married Jane Carter,

No damsel look’d smarter;

But he caught a tartar,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs;

Yes, he caught a tartar, John Hobbs.

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs, John Hobbs;

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs!

To ‘scape from hot water,

To Smithfield he brought her;

But nobody bought her …”

What I did not mention in my 2017 piece is that John Ashton noted in his book:

“Wives at the market did not fetch good prices; the highest I know of, is recorded in The Times, September 19, 1797: “An hostler’s wife, in the country, lately fetched twenty-five guineas.” But this was extravagance, as, with the exception of a man who exchanged his wife for an ox, which he sold for six guineas, the next highest quotation is three and a half guineas; but this rapidly dwindled down to shillings, and even pence. In 1881, a wife was sold at Sheffield for a quart of beer; in 1862, another was purchased at Selby Market Cross for a pint; and the South Wales Daily News, May 2, 1882, tells us that one was parted with for a glass of ale. Sometimes they were unsaleable …”

Fascinating, but horrific when you think about it. In any case, you will be pleased to know that although I visited Smithfield with my wife a few days ago, I had no intention of selling her! Instead, we enjoyed some liquid refreshment in the nearby branch of the Pret A Manger café chain.

April 9, 2024

“Dreams Have No Titles”: An exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London

IT DISAPPOINTS ME when I sleep without being aware of dreaming. Even nightmares are better than no dreams at all. What I enjoy about dreaming is that what I perceive in my dreams is on the one hand so realistic – lifelike and credible, and on the other hand simultaneously so completely unrealistic. The art of cinema can achieve the same ambiguity between realism and fantasy, which is why I enjoy watching films. Until the 12th of May 2024, there is an excellent exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, which explores what I enjoy about films and dreams. Called “Dreams Have No Titles”, it displays the multi-media creations of the Franco-Algerian artist Zineb Sedira, who was born in 1963 – the first year that Algeria was independent of the French, who had colonised it since 1830.

The exhibition, which was first shown in the French pavilion at the Venice Biennale of 2022, consists of a series of film sets. On one of the film sets, an elegantly dressed couple of actors perform ballroom dancing ( https://youtube.com/shorts/kUrD3aJP9s0?si=zez0VWoRqWmJMy4l ) for a few minutes at various times of the day. Each film set reproduces a scene from one of several films made in the 1960s – each one referencing events that took place during the period when Algeria was fighting for its independence. Within the film sets there are video sequences about that period, and about the artist and her life. Born in France, she came to the UK in 1986. One of the exhibits is a wonderful film with the same title as the exhibition. In it she explores film, its creators, its actors, imagination, dreams, and her artistic approach. Each of the film’s 24 minutes is wonderful. The film and other video works in the exhibition are in harmony with what I find so similar between experiencing dreams and watching cinematic films. I came away from the exhibition feeling elated and full of admiration for Zineb and her artistic work.

April 8, 2024

Taking the scenic route from St Pauls cathedral to Paddington

ONE AFTERNOON IN April (2024), out of curiosity we travelled by bus number 46 from Smithfield to Paddington station instead of taking the much faster Underground train route. As we proceeded along the whole route of the number 46 bus, we realised that it links several places of interest to both Londoners and visitors to the city.

The 46 starts within easy walking distance of the BARBICAN CENTRE, SMITHFIELD MARKET, ST BARTHOLOMEW THE GREAT, and THE LONDON MUSEUM. Also, its first stop outside ST BARTHOLOMEWS HOSPITAL is not far from ST PAULS CATHEDRAL.

When the bus gets moving, you will soon pass the ornate Victorian HOLBORN VIADUCT and HATTON GARDEN – famed for its diamond merchants. Next, you will see the Victorian gothic PRUDENTIAL BUILDING and before turning on to Grays Inn Road, you will see a row of half-timbered houses – some of the only PRE-FIRE OF LONDON survivors. Much of the west side of Greys Inn Road is lined with the buildings of GREYS INN – one of London’s four historic Inns of Court.

KINGS CROSS STATION and the magnificent Victorian gothic ST PANCRAS STATION are the next things to look out for. You could leave the bus here to explore the new developments around Kings Cross including COAL DROP YARD and KINGS PLACE hall and events centre. If you remain on the bus, you will head north past the ROYAL VETERINARY COLLEGE to the not over attractive KENTISH TOWN. At CAMDEN ROAD STATION, you will not be far from the REGENTS CANAL and the popular CAMDEN MARKET.

Heading northwards, the 46 reaches Fleet Road in south Hampstead, which is a short walk from the famous Modernist ISOKON BUILDING in Lawn Road. You could disembark at South End Green and visit Mirko to enjoy refreshments in his small MATCHBOX CAFÉ. HAMPSTEAD HEATH is a few minutes’ walk away. If you remain on the bus, you will pass the ROYAL FREE HOSPITAL and next to it, the Victorian gothic ST STEPHENS CHURCH designed by SS Teulon.

The bus then heads up Rosslyn Hill into the heart of historic HAMPSTEAD, where there is plenty for the visitor to explore. Then, the 46 descends the steep Fitzjohns Avenue to Swiss Cottage. Just before it reaches there, look out for the statue of SIGMUND FREUD at the southern end of the Tavistock Institute. The house where Freud lived, now THE FREUD MUSEUM, is close by.

After passing St Johns Wood Station with its several scraggly palm trees, the bus winds its way through streets near Maida Vale until it reaches Warwick Avenue Underground station. Descend here to walk to the REGENTS CANAL near to where it enters the scenic LITTLE VENICE.

Soon, after passing beneath the elevated WESTWAY, the 46 heads for its last stop, which is on a bridge from which you can get a good view of the wonderful glass and ironwork roof of PADDINGTON STATION – a masterpiece of Victorian engineering. From Paddington, there are a few bus routes that will allow you to continue your London sightseeing.

April 7, 2024

A Dutch name on a gravestone in the City of London

AT THE OLD BAILEY court on the 18th of February 1767, Edward Wild was formally accused (indicted) of stealing 25 yards of woollen cloth worth £10 from the widow, Winifred Vanderplank (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/17670218), and found guilty. At the trial, Winefred’s son Bartholomew Vanderplank told the court:

“I live in Bartholomew-close with my mother; I am a cloth-worker. Last Monday three weeks, the piece of cloth mentioned was taken away; the prisoner at the bar was stopped with it; I was before Justice Welch when he and the cloth was; he there confessed he took it away.”

According to “The records of St. Bartholomew’s priory and of the church and parish of St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield” (publ. 1921), Mr Vanderplank lived close to the Church of St Bartholomew the Great, formerly part of the Priory that existed there until it was disbanded and partially demolished during the reign of King Henry VIII. The records stated:

“… The house of Mr. Vanderplank close by (he lived at No. 54 [ i.e., Bartholomew Close]) was the monastery kitchen from which a subterranean passage communicated with the church, persons having passed through it to the knowledge of the proprietor.”

The same records revealed that the Vanderplanks lived at 54 Bartholomew Close:

“In the London Directory of 1770, No. 54 was in the occupation of the Vanderplanks, cloth workers, who lived in the parish until the middle of the nineteenth century.”

You might be wondering why I should be telling you about a family whose surname indicates that it probably has Dutch origins. Well, the reason is that yesterday (the 2nd of April 2024), I was in the church of St Bartholomew the Great (near Smithfield Market) when I looked at the floor and spotted the gravestone recording the deaths of several members of the Vanderplank family, including that of Bartholomew, who appeared in court on the 18th of February 1767.

Regarding Bartholomew, he was affiliated to the City of London’s Clothworker Company (guild) (https://londonroll.org/search), as were some other members of the family, who lived in Bartholomew Close. I have not yet been able to find out when exactly the Vanderplank family settled in England, but I have read (www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/lond...

“The Flemish and Dutch arrived in England in large numbers in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and were primarily artisans, especially weavers and other cloth workers. This was partly due to ‘pull’ factors in the form of royal invitations and ‘letters of protection’ issued by the king. The Crown was keen to boost the English cloth industry by encouraging the arrival of skilled foreign workers. However, immigrants from the Low Countries also came due to ‘push’ factors, especially the hardships caused by warfare in the region and sentences of mass exile in the late fourteenth century for participating in revolts in Flanders.”

The top of the stone reads:

“Here lieth the Body of Barthow Vanderplank Late of the Parish who died July 19 1792 aged 48 years.”

The stone also commemorates the deaths of other members of his family – his wife and children. Because I was curious about the surname, I did a little research on the Internet, and found what I have just described.

April 6, 2024

William Hogarth and Damien Hirst as neighbours in a church in London

ST BARTHOLOMEW THE GREAT church in the City of London was founded in 1123 by Rahere, a courtier of King Henry the 1st, who reigned from 1100 to 1135. It was originally built as the church for an Augustinian priory, which was abolished and partly destroyed during the reign of King Henry VIII. When this happened (in 1539), the priory church’s nave was demolished, leaving only the apse and beyond it, the Lady Chapel. The choir, which used to be at the west end of the apse and at the eastern end of the demolished nave, now stands at the east end of what is now the nave, but was formerly the apse. The current nave (formerly the apse of the original church) is a magnificent example of Norman architecture. I could go on describing this magnificent church in great detail, but I will not because plenty of people have done it before me (e.g., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Bartholomew-the-Great and https://medievallondon.ace.fordham.edu/exhibits/show/medieval-london-sites/stbartsgreatchurch). Instead, I will mention a couple of the many interesting items in the church that caught my interest during a visit today (the 2nd of April 2024).

Both the objects of interest stand in the southwest corner of the church, close to the entrance that leads to the path that runs along the location of the long-since demolished apse of the priory church. The two things stand a few feet from each other. One of them is a carved stone font, said to be one of the two oldest fonts in London – the other being in the parish church of St Dunstan & All Saints in Stepney. What interested me about St Bartholomew’s font, which is still in use, is that it was here that the painter William Hogarth (1697-1764) was baptised. He had been born in a house in Bartholomew Close near the church in the Smithfield district of London.

Hogarth was a successful artist in his time, and has become recognised as one of the famous British artists of the 18th century. Not far from the font, there is a dramatic gold coloured sculpture by one of the most famous British artists of our times – Damien Hirst (born 1965). The sculpture, which is on loan from the artist, is called “Exquisite Pain.” It is Hirst’s depiction of St Bartholomew holding his skin, having been flayed. The church’s website (www.greatstbarts.com/visiting-us/artworks/damien-hirst-exquisite-pain/) revealed:

“St Bartholomew, one of the original twelve disciples, was sent as an Apostle to Armenia, where he was killed by being skinned alive. The classic iconography of the saint sees him naked, his muscles exposed, his skin hanging over his arm – and in his hands, the instruments of his torture. This statue sees Damien Hirst conform to this imagery, but give it a unique twist: the instrument in his hand is not a standard knife, but a scalpel, used in the hospital across the road which also bears the saint’s name.”

I think it is a wonderful sculpture. However, like most works of art, it might not suit everyone’s taste, but there is no doubting that its dramatic impact and skilful execution are remarkable.

While Hirst’s fame is great today, and his works command high prices, I wonder whether his reputation as a notable British artist will survive as long as Hogarth’s.

April 5, 2024

From the screens of Instagram onto the walls of commercial art galleries

DO NOT UNDERESTIMATE the power of Instagram.

Today (the 2nd of April 2024), we visited Beers Gallery in Little Britain, a street which is close to St Bartholomew the Great church and Smithfield meat market. Until the 13th of April 2024, they have an exhibition of delightful paintings by Florent Stosskopf, who was born in Rennes (France) in 1989. Based in Brittany, he has qualifications in web and graphic design, as well as holding an Advanced Technician diploma from L’école Multimedia. Yet, he is a self-taught painter. His current exhibition at Beers is called “The Mocking Bird”. The gallery’s press hand-out says:

“The title, he informs us, is a loose reference to elements of his own autobiography that he found mirrored in the song ‘Mockingbird’ by Eminem.”

Be that as it may, the paintings are full of bold colour and vibrancy. It was a joy to see them.

We had never heard of Florent Stosskopf. We asked a lady who worked in the gallery how her establishment had got to know of this artist. The answer astonished us. She told us that it was after he began posting pictures of his paintings on Instagram (see: www.instagram.com/stosskopf_florent/) that he began to be recognised as being a painter worth exhibiting in commercial galleries.

Many people with artistic tendencies and varying degrees of skill post images of their creations on Instagram. Even I use Instagram to try to promote some of my books. However, just posting on Instagram is not enough. To become truly successful by using Instagram, you need real talent, and that is what Monsieur Stosskopf has in a large amount.

April 4, 2024

Victorian photographs exposed at London’s National Portrait Gallery

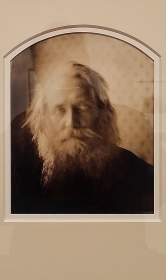

JULIA MARGARET CAMERON (1815-1879) was born in Kolkata (Calcutta) and died in Sri Lanka. When her husband retired from the Indian civil service, she and her family bought a house on the Isle of Wight, close to that of her friend, the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson. From an early age, when she met the astronomer and chemist Sir John Herschel in Cape Town, she developed an interest in the relatively young technique of photography. It was only in 1863 when she was residing on the Isle of Wight that she was given her first camera. This was the start of her remarkable career as a photographer. Unlike many other photographers during the Victorian era, Julia was not interested in producing exact images of her subjects in her photographs. Instead, she experimented with lighting, focus, development, and printing, to produce photographic images that were artistic rather than accurate representations of reality. Her subjects included many of the cultural giants of mid to late Victorian Britain. Also, she loved to pose her subjects, dressed in imaginative fancy dress costumes, in intricately contrived tableaux before capturing their image on photographic plates.

Until the 16th of June 2024, there is a temporary exhibition of photographs by Cameron at London’s National Portrait Gallery. Many of Julia’s photographs are on display alongside those of another woman photographer, Francesca Woodman (1958-1981). Although Woodman’s photographs are of a high quality artistically, seeing them alongside those of Julia Margaret Cameron added little to my enjoyment of the exhibition. However, this show does give impressive exposure to Cameron’s pioneering work in using photography as an art form rather than as a medium for recording likenesses. As exhibitions go, I did not feel that this one is a sparkling example of curating. However, I am pleased that I went because I have read a great deal about the life and times Julia Margaret Cameron, and have also published a short book about her, which is available on Amazon: