Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 56

April 3, 2024

A walk in the sunshine on a Saturday morning in north London

AFTER DAYS OF GREY skies, the sun shone without pauses today (the 30th of March 2024). This was lucky because come rain or shine, we had decided to walk south from Primrose Hill through Regents Park to Marylebone Road. Much of the way we passed places with fond memories for us. The first of these was Chalk Farm Underground station. It was near here that my wife used to live in a flat on Fellowes Road long before we married.

From the station, we walked across a graffiti-covered iron bridge that crosses the mainline railway tracks from Euston. This brought us to the eastern end of Regents Park Road (‘RPR’). Lined with shops and eateries, this curving road is where we met with our friends frequently. One of our favourite places was Lemonia – a Greek restaurant. When it first opened, it was on the south side of the road. Now, it occupies larger premises on the north side of RPR. After having coffee at Roni’s, an Israeli café that did not exist in the 1980s when we often visited the area, we walked towards the base of Primrose Hill. Today, being the Easter weekend, the road was far less busy than it is on other weekends.

Looking down from Primrose Hill

Fortified with coffee and a croissant, we ascended the steep path leading from opposite the house where Friedrich Engels once lived to the summit of Primrose Hill, which had attracted a crowd of people who had come out to enjoy the sun and the magnificent view of London to the south of the hill. While we were descending the hill towards Regents Park, a young lady, who was ascending the hill with her husband and two children, greeted us. I did not recognise her as I had not seen her for 21 years, and (then only briefly) when she was a young teenager. She is the daughter of one of my cousins, and the great-great granddaughter of my ancestor Franz Ginsberg, who was a Senator in the parliament of South Africa between the two world wars.

After reaching the bottom of Primrose Hill, we crossed Prince Albert Road, and then walked over a bridge that traverses the Regents Canal. At the south end of the bridge, we passed some enclosures (containing what looked like large wild boars or warthogs) of the London Zoo. Then, we walked along a straight path between grassy playing fields – not particularly scenic. In the distance we could see the minaret of the Regents Park Mosque and the domes on the roof of the London Business School, where my wife studied. Eventually we reached a more attractive area close to the eastern edge of the Boating Lake, over which we crossed on a bridge. Soon, we arrived at the circular road, appropriately named the Inner Circle. It seemed to being used as an unofficial racetrack for cyclists on expensive looking bicycles. Having safely crossing the road without being hit by a cyclist, we entered the round heart of Regents Park, which contains the famous Queen Marys Rose Garden.

We took refreshments at the strange-looking Regent’s Bar & Kitchen. In plan, it is a collection of identical adjacent hexagons. The roofs of some of these have sharp conical pinnacles. From there we passed beds of rose plants. All of the roses were without flowers, A small wooden bridge crosses a stretch of water – part of a larger pond – to reach the attractive Japanese Garden Island from which you can see a man-made rocky waterfall designed as it would be in gardens in Japan.

After wandering around the Japanese garden, we headed towards the Inner Circle, which we crossed before walking south along a road called York Bridge because it crosses a body of water by means of of a similarly named Bridge. Before reaching the bridge, we passed the buildings of Regent’s University. These used to house a part of the University of London – Bedford College. Founded in 1849, it was for the higher education of women. From 1878 onwards, women studying there were awarded degrees by the University of London. In 1984, after Bedford College had merged with Royal Holloway College, its premises in Regents Park became the home of Regent’s University, which is not affiliated to the University of London. Interestingly, the wrought iron gates to Regent’s University’s grounds still bear the crests of its predecessor – Bedford College. In the 1920s, my wife’s maternal grandmother, Benabai Bhatia, who had come from India with her husband Haridas, who was studying for an FRCS, studied at Bedford College. On her return to India and after she was widowed at a young age, she became a superintendent of schools in Bombay.

After crossing York Bridge, we soon reached Marylebone Road, having had a thoroughly enjoyable walk.

April 2, 2024

A small exhibition of watercolours at London’s Wallace Collection and an artist who was unknown to me

SEVERAL OF THE GALLERIES within London’s Wallace Collection in London’s Manchester Square, have an overwhelming number of paintings crowded together on their walls. One of these galleries contains several paintings by Richard Parkes Bonington (1802-1828), which I doubt I would have focussed on had I not just seen a small temporary exhibition in a room on the ground floor. The exhibition is called “Turner and Bonington: Watercolours from the Wallace Collection”, and is on until the 12th of May 2024. It contains 10 watercolours (of landscapes) held by the Wallace Collection – four by JMW Turner (1775-1851) and the rest by his short-lived contemporary Bonington. Each of the watercolours is delightful and well-executed. Bonington’s watercolours are delicately crafted, but less adventurous than those of Turner. Because they are so sensitive to damage by light, these watercolours are rarely displayed. The last time they were exhibited was 17 years ago.

Watercolour by Bonington

Now, I had heard of Turner and have seen many of his works, but today (the 29th of March 2024) was the first time I became aware of Bonington. He was born near Nottingham and by the age of 11 was exhibiting watercolours at the Liverpool Academy. In 1817, he and his family moved to Calais (France), where his father set up a business. From there they moved to Paris in 1818. During his time in France, Bonington learned painting from French artists and soon became a friend of the French artist Eugene Delacroix. In 1820, he became a student at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Some of his oil paintings were displayed in the Paris Salon of 1822, and elsewhere. By 1825, he had developed a method of mixing gouache with watercolour, which produced an effect close to what could be achieved with oil paints. After making trips to various parts of France, northern Italy, Venice, and London, he developed tuberculosis. He died in London, where his parents had sent him for treatment. In 1861, many years after Bonington died, Delacroix wrote in a letter (quoted in a Wikipedia article):

“To my mind, one can find in other modern artists qualities of strength and of precision in rendering that are superior to those in Bonington’s pictures, but no one in this modern school, and perhaps even before, has possessed that lightness of touch which, especially in watercolours, makes his works a type of diamond which flatters and ravishes the eye, independently of any subject and any imitation.”

I wish I could have thought of those words, which chime with what I thought after seeing Bonington’s watercolours and some of his many oil paintings now hanging in the Wallace Collection – a London address that no art lover should miss visiting.

April 1, 2024

An unexpected story told in a cafe in London’s North Kensington

LAST YEAR I READ a fascinating book, “Staying Power”, written by Peter Fryer and first published in 1984. It is a history of black people in Britain from the time of the Roman conquest until 1984. In it, the author gives plenty of examples of the hostile reception that black people arriving in Britain received from their racist British neighbours and workmates.

Today (the 28th of March 2024), I was sitting in the Lisboa Patisserie, a cafe in North Kensington’s Golborne Road, when I began chatting about the ‘good old days’ with a gentleman, who is a few years older than me. He told me that he had come to Britain from the West Indies in the early 1950s when he was 8 years old. Having read Fryer’s book and having heard stories of racist behaviour, I asked him whether it had been difficult for him and his family after they arrived in England. I was astonished and very pleasantly surprised by his reply.

He told me not to believe that everything was as bad as is often recorded. From the moment his family arrived, the English people they encountered were all very kind and friendly. As an example, he described what happened when his family were evicted from their flat by their (black) landlord. They were literally out on the street with nowhere to go. Two English (i.e., white) ladies, who were chatting to each other over a garden fence, saw them, and asked what had happened. Hearing their plight, one of them said that she had a spare room in her attic, where they could live until they found somewhere of their own.

The gentleman in the café told me that once they had settled into new accommodation, they were at a loss as to how to deal with things that they had not had previously encountered in the West Indies. For example, back in the Caribbean, their home did not have electricity or gas or many other domestic things that were usual in British homes in the 1950s. It was their white milkman, who came to their rescue. If there was something they could not deal with – for example replacing a fuse – their milkman would come into the house and help them out.

Our friendly neighbour in the café said that he could give me many more examples of kindness and friendliness of white British people, which his family had encountered. However, as he could see that we had finished our coffees, he concluded by saying that contrary to, as he put it: “what millennials only want to hear”, it was not all bad as far as white British behaviour towards immigrants from the Caribbean were concerned. He did not know that I do a lot of writing, but he said that I should write down what he told us as it needed to be known – and that is what I have done.

I must add that his story is somewhat unusual because even today, we still hear of too many cases of intolerance and even harm to Afro-Caribbean people.

PS: although this has been published on the 1st of April, it is NOT an April Fool’s joke!

March 31, 2024

A sign on the pavement that points to a place that no longer exists

THE EAST SIDE of London’s Russell Square is lined by large hotels, one of which is the Imperial. On the pavement where Guilford Street enters the eastern side of Russell Square, there is some lettering, which reads:

“Turkish Baths”.

Beneath this is an arrow pointing southwards, and below that, the word:

“Arcade”.

Kimpton Fitzroy Hotel in the background

If you follow the arrow, you will pass the west facing side of the 20th century Imperial Hotel, but you will not neither an arcade nor any Turkish baths. You will pass a vehicle entrance to a courtyard within the hotel. Being puzzled by this old, and it seemed redundant, writing on the pavement, I researched it on the Internet, and soon found out something about it (see for example: https://carolineld.blogspot.com/2012/11/turkish-baths-russell-square.html & www.londonremembers.com/sites/imperial-hotel-statues)

The current Imperial Hotel was built in the late 1960s on the site of an earlier hotel of the same name (built in 1898), which was demolished, rather than restored, in 1966. It was in this first Imperial Hotel that the Imperial Turkish Baths were located. These were demolished along with the hotel that contained them. However, some statues that used to decorate the highly ornate baths were rescued, and now surround the above-mentioned courtyard.

The lettering on the pavement is outside the entrance to a Pret A Manger café. This eatery stands on the site of the former Librairie International bookshop, which might well have been a place where Communist and Anarchist publications were sold. A web page that describes this shop (https://alondoninheritance.com/london-parks-and-gardens/russell-square-and-librairie-internationale/) revealed:

“I have found references to the Librairie Internationale selling copies of Karl Marx publications in the 1920s and in the 1930s as one of the bookshops in London where you could purchase pamphlets such as those produced by the London Freedom Group, whose paper “Freedom – A Journal of Libertarian Thought, Work And Literature” included the address of the Librairie Internationale in Russell Square as one of the London bookshops and newsagents where Freedom could be purchased.”

I had never heard of this bookshop or the Turkish Baths at the Imperial Hotel, and would not have known about either of them had I not noticed the lettering in the pavement. I spotted this after having met a person, whom I had not seen since 1968, when we were both pupils at north London’s Highgate School. We had just met for coffee at a café within the Kimpton Fitzroy Hotel, which was built as The Russell Hotel and opened in 1900. Unlike its neighbour The Imperial, it was not demolished and replaced by something newer. The old Imperial would have been built in the same flamboyant style. Having noticed my interest in signs, my friend from schooldays pointed out another sign on the north side of the Kimpton Fitzroy. It commemorates the fact that a house where the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) lived with her daughters (Christabel and Sylvia) between 1888 and 1893. The house was demolished – possibly to make way for the construction of the hotel, which began in 1898.

Everything I have described above lies within a stretch of road less than 200 yards in length. And I have said almost nothing about the historic Russell Hotel that lies along this stretch. This and many other parts of London are so rich in history, which is one of many reasons that I am happy to be a resident of the city.

March 30, 2024

sunlight through petals on a tree

March 29, 2024

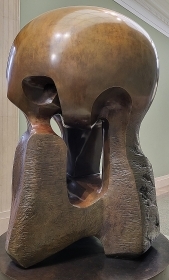

Moore and the atomic mushroom cloud at the Tate Gallery

LAST YEAR, THE exhibits at Tate Britain were re arranged – or ‘rehung’ as the gallery likes to put it. In addition to rearranging the paintings and sculptures – very excellently I might add – previously unseen exhibits were added to the galleries. One of these is in a small gallery containing sculptures and some drawings by the British artist Henry Moore (1898-1986).

The additional exhibit in this gallery devoted to Moore is a glass cabinet containing a Ban the Bomb poster – a photomontage – designed by Henri Kay Henrion (1914-1990). I went to school in Belsize Park with one of his sons for a few years. The rest of the contents of the cabinet are documents – mainly press cuttings – about one of the sculptures near to the cabinet. They relate to a sculpture Moore created for the University of Chicago. The bronze sculpture, which at first sight resembles a combination of an atomic ‘mushroom cloud. with a distorted face beneath it, is called “Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy)”. The Tate’s website (www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/henry-moore-om-ch-atom-piece-working-model-for-nuclear-energy-r1171996) explained:

“As its subtitle suggests, Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5 represents the intermediary stage in the development of a much larger sculpture, Nuclear Energy 1964–6, which Moore was commissioned to make for the University of Chicago to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first controlled generation of nuclear power, conducted by the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi in 1942.”

The sculpture next to the cabinet is one of 13 bronze castings that Moore had made from one of his plaster maquettes that were created whilst planning the larger sculpture commissioned by the University of Chicago. Moore donated it to the Tate.

The photomontage by Henrion shows a human skull superimposed by a mushroom cloud. He created it in about 1959. The Tate’s website mentioned that Moore was most probably aware of Henrion’s terrifying image long before he created the sculpture for Chicago:

“Moore is likely to have been familiar with Henrion’s photomontage: in 1950 he had signed a letter published in the Times protesting against the potential use of atomic weapons, and in 1958 had become one of the founding sponsors of the CND.”

Although I have seen the ‘atomic’ sculpture by Moore at Tate Britain many times, I had not taken any special interest in it. However, thanks to the superb ‘rehang’ at the gallery and the addition of the glass case containing Henrion’s image, I began to appreciate the atomic sculpture, and strangely also began to enjoy Moore’s sculptures even more than I had before.

March 28, 2024

Swamp Cypress and Skunk Cabbage in a park near Hampton Court

I ALWAYS ENJOY visiting Bushy Park, which is near to London’s famous Hampton Court Palace. Parts of the park are unenclosed, where plenty of deer roam at liberty. Other parts – the Pheasantry and Waterhouse plantations – are enclosed by fencing to keep the deer excluded.

The plantations contain a rich variety of plants and trees, all of which are a joy to see. There are two types of plants that never fail to fascinate me. One of these is the swamp cypress trees (Taxodium distichum). What makes them interesting is their aerial roots (known as ‘Cypress Knees’), which look like small woody stalagmites or tapering tree trunks. You can see rows of these stumpy aerial roots lining the stream near to the Pheasantry Café. According to a web article (www.graftingardeners.co.uk/trees-of-bushy-park/), these trees were:

“Once native to Britain, there have been ancient remains of this tree species found in Bournemouth. However, the swamp cypress was reintroduced to Britain by John Tradescant the Younger in 1640 … When the ground is particularly waterlogged, the swamp cypress tree grows pneumatophores. These are like knobbly woody stumps that grow out of the ground and serve as a sort of snorkel.”

Skunk Cabbage flowers

The other plant that stands out in my mind is known as Skunk Cabbage. With yellow flowers that slightly resemble Arum lilies, the Skunk Cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) is believed to emit an odour similar to that of skunks when it blooms. The smell is attractive to pollinators. The plant, although interesting to look at is a potential pest, as I found out on a website that deals with invasive species (www.invasivespecies.scot/american-skunk-cabbage):

“The large leaves and dense stands of the plant lead to it out-competing smaller plants due to its shading effect and can cause extensive damage locally to native flora including vascular plants and mosses. It can grow in shade or full-light and in a range of different soil conditions and thrives in disturbed environments. Given the popularity of this plant in gardens and its continued introduction into the wild, the problems are likely to increase. Although initial invasions will expand slowly, once this plant takes hold it can spread rapidly and become a serious problem.”

We saw the Skunk Cabbage in various stages from bud to full bloom when we visited Bushy today (the 24th of March 2024), but could not get close enough to the flowers to smell the odour from which they have got their name. I had noticed these plants before, but until today I did not know what they are.

Seeing curious plants such as the Swamp Cypresses and the Skunk Cabbage, which, incidentally, is edible if its root is roasted and dried, adds to the pleasure that is gained from seeing Bushy’s less strange plants such as daffodils, camellias, rhododendrons, and so on. Visiting the park and its gardens is well worthwhile, but get there early in the morning to ensure finding a place in the car parks.

March 27, 2024

Fading signs painted on a building near London’s Holborn

TWO FADED SIGNS CAUGHT my attention when I was walking along the east side of Southampton Row (just north of Holborn Underground station). The sign is on the southern side of the intersection of Catton Street and Southampton Row. The two faded, painted signs are separated by another which is carved on a stone plaque, and is clear to read. This sign reads:

“This memorial stone was laid by Alexander Maclaren, DD,, Litt D. President of the Baptist Union 1875-6 and 1901-2 on Wednesday 24th of April 1901”

Above this, there is a painted sign that can easily be read:

“To Kingsgate Baptist Church”

Below these two signs, there is another painted sign,a ‘ghost sign’, which has deteriorated considerably, but parts of it can either hardly be read or are illegible. Here is what I made of it:

“The CA[illegible] [2 more illegible words] Kingsgate House Acc[illegible] &(?) Warehouse Church Furniture”

An online article published in July 2020 in Italian (www.thelondonerd.com/tag/statua/) revealed that then, when the sign was more legible, it read:

“The Carey Kingsgate Press Ltd. – Accountancy – Warehouse – Church Furniture”

This web article also includes lovely photographs of the now re-purposed Kingsgate Chapel.

The three notices are on the corner of Kingsgate House, which was built between 1901 and 1903 for the Baptist Church. It was designed by Arthur Keen, architect for the Baptist Union of Great Britain and Ireland. The Baptists used the building up to 1996. Since then, it has been repurposed.

As for the Kingsgate Chapel (the ‘Kingsgate Baptist Church’ on the fading sign), this can now only be accessed by entering Kingsgate House. Constructed in 1856, it is attached to the northeast corner of the building. No longer accessible to the public and hidden away, it is an octagonal building that can be seen on detailed maps of today. When it was in use as a chapel, its entrance would have been just east of Kingsgate House on Catton Street (formerly known as Eagle Street). Close to where its entrance used to be, there is the entrance to the Baptist Bar, which is now housed in the former chapel.

The ghost sign mentions a warehouse and church furniture with an arrow pointing east along Catton Street. This must have been demolished many years ago. I spotted the fading signs whilst returning home late one evening. Now, having found out something about them, I look forward to returning to Kingsgate House and having a drink in the former chapel – if the bar is still open for business.

March 26, 2024

A lovely garden just east of a huge supermarket in North Kensington

IF YOU WALK EASTWARDS from the canal side of Ladbroke Grove’s huge Sainsburys supermarket, the towpath alongside the Grand Union Canal (Paddington Arm) next runs alongside Meanwhile Gardens. There are several apertures through which one can enter the gardens from the towpath, and you can also gain access to the place from the streets that surround it.

In my book “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London” I wrote:

“In 1976, the Meanwhile Gardens were conceived as a green space for the local, then generally low-income, mixed-race community, by Jamie McCollough, an artist and engineer. They were laid out on a strip of derelict land, which once had terraced housing and other buildings before WW1. The garden received financial assistance from the Gulbenkian Foundation and other organisations. The garden was, according to circular plaques embedded in its pathways, improved in 2000.

The Garden and the Sainsbury supermarket are in a part of London that used to be known as ‘Kensal Town’. Residential buildings began appearing in the 1850s and many local people were employed in laundry work and at the gasworks of the Western Gas Company that was opened in 1845. In the 1860s and 1870s, there was much housebuilding in and around the area now occupied by Meanwhile Gardens.Golborne Road was extended to reach this area in the 1880s. Many of its inhabitants were railway workers and migrants, whose homes in central London had been demolished. The area was severely overcrowded and extremely poor. Few houses had gardens and the population density was high.

After WW2, many of these dwellings were demolished and replaced by blocks of flats, including the impressive, Brutalist style Trellick Tower (designed by Ernő Goldfinger [1902-1987], opened in 1972) and smaller but salubrious shared dwellings.

A winding path links the various parts of the lovely garden including a sloping open space; a concrete skate park; a children’s play area; several sculptures; small, wooded areas; some interlinked ponds with a wooden viewing platform; plenty of bushes and shrubs; bridges; and a walled garden that acts as a suntrap. Near the latter, there is a tall brick chimney, the remains of a factory. The chimney was built in 1927 near to the former Severn Valley Pure Milk Company and the Meadowland Dairy. It was the last chimney of its kind to be built along the Paddington Arm canal and is completely dwarfed by the nearby Trellick Tower.

The Moroccan Garden, an exquisite part of the Meanwhile Gardens, was opened in 2007 by Councillor Victoria Borwick on behalf of the local Moroccan community. It celebrates the achievements of that community and is open for all to enjoy. A straight path of patterned black and white tiling leads from the main path across a small lawn to a wall. A colourful mosaic with geometric patterning and a small fountain is attached to the wall, creating the illusion that a tiny part of Morocco has been transported into the Meanwhile Gardens. Nearby, there are a few seats for visitors to enjoy this tiny enclave within the gardens.

Words are insufficient to fully convey the charm of the Meanwhile Garden, one of west London’s many little gems. If you can, you should come to experience this leafy oasis so near the busy Harrow Road.”

If this short extract from my book that explores parts of west London – both familiar and unfamiliar – head for Amazon, where you can buy the book as a paperback and as a Kindle:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/BEYOND-MARYLEBONE-MAYFAIR-EXPLORING-LONDON/dp/B0B7CR679W/

March 25, 2024

Taking the plunge in a cold bath at Kenwood in north London

I HAVE VISITED Kenwood House and its grounds innumerable times since my childhood, but it was only today (the 21st of March 2024) that I have been able to enter a part of it that has always been locked up whenever I have been there before. I am referring to a small building known as “The Bath House”. It is close to the courtyard where there are tables and chairs for visitors to use while enjoying refreshments.

A short staircase leads down to the door of the Bath House, which was probably already in existence when the Mansfields bought Kenwood and its grand house in 1754. The interior of the small edifice contains a circular pool. The wall around the marble-lined pool has several alcoves, and the concave ceiling is a plastered circular dome. What can be seen today is that is a faithful reconstruction of what had been there originally.

The pool used to be filled with cold water from one of the many iron-rich chalybeate springs in the area. In the 18th century, the chalybeate springs in nearby Hampstead were almost as famous and as much visited as those in Royal Tunbridge Wells (in Kent). The inhabitants of Kenwood House used to plunge themselves into the cold water because it was considered to be beneficial for health reasons in the 18th century.

It was only the select few who had the luxury of taking the plunge in such an elegant pool as can be seen in Kenwood. The other locals living in Hampstead had to make do with bathing in the many ponds that can still be seen dotted around Hampstead Heath. Within Kenwood House today, we saw a painting by John Constable (1776-1837) that depicts one of these ponds being used by bathers. For many years, the artist lived in Hampstead.

Small though it is, it was exciting to see within the Bath House at long last. For many decades, I have wondered what was within it, and now my curiosity has been satisfied.