Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 37

October 9, 2024

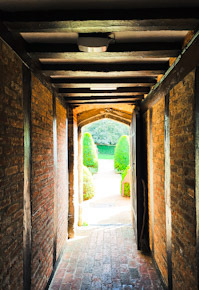

A picture posting

Ewelme, Oxfordshire

The light at the end of the tunnel can be blindingly bright.

October 8, 2024

A redundant church by the River Thames in Oxfordshire

WALLINGFORD IN OXFORDSHIRE stands on a bank of the River Thames. There is a bridge across the river. If you stand on it, facing the town, you will notice a church with an unusual spire standing near the river. This is the church of St Peters. It was built between 1763 and 1769 on the site of an earlier church, which had been demolished by Parliamentary forces in 1646, when the town was being besieged by them.

Largely unaltered since it was constructed, the church contains the grave of the famous lawyer Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780), a judge who was the author of the still influential “Commentaries on the Laws of England”. He was elected as one of the first church wardens of St Peters. Sir William contributed generously to the construction of the steeple and the installation of a clock on the south face of the tower.

On the 29th of June 1969, the last service to be held in the church took place. St Peters became officially redundant in April 1971, and its care was taken over by the Redundant Churches Fund a year later. This organisation was founded in 1969. In 1994, the organisation was renamed The Churches Conservation Trust. This admirable group currently look after more than 350 redundant churches in England, and keep them open to the public and in an excellent state of preservation. We have visited many of their churches over the years, and found them to be interesting and usually very beautiful.

October 7, 2024

Flowering in October

Ewelme, Oxfordshire

Ewelme, Oxfordshire Autumn blooming

In an English country churchyard

Roses I believe

October 6, 2024

Transported from Florence (Italy) to South Kensington (London, UK)

WHILE WAITING FOR an item to be delivered to me at the National Art Library, which is housed within the Victoria and Albert Museum (‘V&A’) in South Kensington, I had time to look around the museum. The V&A is a treasure house filled with fascinating exhibits from all around the world. Today, I noticed something that had not caught my eye before. It is an entire Italian Renaissance chapel, which was transported from Florence to its present location in the V&A.

This chancel chapel used to be part of the Santa Chiara convent in Florence. The convent belonged to the Poor Clares, who were female branch of the Franciscan order. Mass used to be held in this small chapel, which was constructed in the first half of the 15th century. Following the 1808 Napoleonic suppressions (of Italian religious orders), the chapel became used as a sculptor’s studio in the 1840s and 1850s. The V&A’s website (https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17758/chancel-chapel-from-church-of-chapel/#object-details) revealed:

“In 1860, J. C. Robinson bought the chapel on behalf of the V&A, and it was dismantled and shipped to London, whereupon it was reassembled in the North Court of the Museum … In 1908 the chapel was moved from the North Court to the eastern apsidal end of the Aston Webb wing of the museum, parallel to Cromwell Road, where it remains today.”

Because of its relocation to London, the chapel is the only example of an Italian Renaissance chapel to be seen outside Italy. Moving this chapel was a less ambitious achievement that what can be seen at the Met Cloisters in Manhattan. At this museum, several entire cloisters, which had been removed from France, have been reassembled for visitors to see. Heaven forbid that the Italians will begin demanding to return the chapel, and that the French will seek repossession of their cloisters. I feel that these repatriations are even less likely than the Elgin Marbles being sent back to Greece.

October 4, 2024

A cultural centre beneath a Victorian clocktower in Croydon

THE DAVID LEAN cinema, where we watched a superb film called “Coming to America” (made in 1988), is within a complex known as the Croydon Clocktower. In the heart of Croydon, this cultural centre is housed in what was originally constructed as the district’s Town Hall.

The Town Hall is a magnificent – exuberant – example of Victorian brickwork. It was constructed to the designs of a local architect, Charles Henman, and inaugurated by the Prince of Wales in 1896. There is a large statue of his mother, Queen Victoria, outside the façade on Katherine Street.

Until the 1980s, the enormous edifice was used for local government purposes. In the late 1980s, and early 1990s, the interior was renovated. Areas that were no longer needed for council business were repurposed as a public library, a café, a museum, and the David Lean cinema. A large room, which retains its original interior décor, the Braithwaite Hall, continues to be used for concerts, theatrical shows, and other public functions. It looked to me that the inside of the building had been hollowed out to create a spacious central atrium with a glass roof, which can be overlooked from galleries surrounding it on each floor. The result is pleasing to the eye. From the outside of the building, you would not expect to see this kind of atrium. The Town Hall complex is now known as the Croydon Clocktower, the name referring to the building’s high brick clock tower.

The film we watched in the small David Lean cinema was wacky but wonderful – a complete contrast to an incredibly slow-moving Taiwanese film, “Days”, which we watched a few days later.

A very slowly moving film from Taiwan

MOST FILMS WE have watched at the Garden Cinema near London’s Holborn have been excellent or extremely excellent. Today, we watched a Taiwanese film called “Days”, directed in 2020 by Tsai Ming-liang. It is one of the slowest moving films I have ever seen. It was not devoid of interest, but it was almost sleep inducing. Lasting about 2 hours, it felt like months, not days.

October 3, 2024

Remembering Princess Diana

October 2, 2024

A nude in London’s Hyde Park cast from cannons

A HUGE STATUE OF a naked man holding up a shield in his left hand stands opposite the London Hilton Hotel, across Park Lane. It looks as if he is defending himself from missiles being hurled from the upper floors of the hotel. Depicting the ancient hero Achilles, it is the Wellington Monument, commemorating the victories of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, and his men who helped achieve them.

The statue was designed by the sculptor Richard Westmacott (1775-1856), it was inaugurated in 1822 by King George IV. On its granite base, there are the names of four of Wellington’s military victories: Salamanca, Vittoria, Toulouse, and Waterloo. The statue was financed by donations given by British women.

Although I think that the statue is unattractive, there are two things about it that I find interesting. It was the first public nude sculpture in London since ancient times. Despite the presence of a fig-leaf, this caused quite a bit of controversy when it was unveiled. The other thing that attracted my attention is that the sculpture was cast from the enemy’s cannons captured at the four places mentioned above, and then melted down.

There is a phrase ‘from swords to ploughshares’. The Wellington Monument must be one of the few examples of ‘from cannons to nudes’.

September 30, 2024

Narrative art in the round at London’s Barbican Centre

THE CURVE AT London’s Barbican Centre is as its name suggests, a curved space. When the Centre was built, the Curve was designed as a space to act as a sound barrier or buffer to contain the sounds emanating from the concert hall that it surrounds. Nowadays, it is used as a space for temporary exhibitions. Until the 5th of January 2025, the Curve will contain an exhibition, “It will end in tears”, of paintings Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, who was born in Botswana in 1980.

Ms Sunstrum’s paintings are on grainy wooden panels, and are truly wonderfully executed. The series of paintings are all linked by a narrative – an imagined story of a woman who lands in a colonial country in Africa in the early to mid-20th century, and has an adventure that ends up with a court case. For this exhibition, the Curve has been divided by wooden partitions into a series of rooms, connected to each other by an elevated walkway. Each room is designed to resemble a different stage set. For example. one is a kitchen. and another is a courtroom. The viewer walks along the walkway from room to room, seeing the series of paintings arranged in the order that the story unfolds. The heroine of the story is an imagined woman named Bettina. The artist created Bettina in her own image – each depiction of Bettina is the artist’s self-portrait. The resulting set of pictures along with the wooden partitions makes for an enjoyable and intriguing experience.

The paintings are like ‘stills’ from a movie. Although their style and subject matter is completely different, I was reminded of series of paintings such as those by Vittore Carpaccio (c1460-c1525) in Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (in Venice), which show scenes from a legend with a Christian religious theme.

Ms Sunstrum’s site-specific exhibition at the Curve is what the series of guidebooks issued by the Michelin tyre company would describe as “vaut la détour” (‘worth the detour’).

A baptismal font in with stone carvings a church in Hertfordshire

WARE IS AN ATTRACTIVE small town on the River Lea in Hertfordshire. Coaches travelling between London and Kings Lynn passed through Ware because it was on the route of the Old North Road (now followed approximately by the modern A10). The parish church of Ware, St Mary the Virgin, is large and spacious as befits the size of the town. Much of what we can see today was built over several centuries, from the 12th to the 15th. It was the church’s stone font that attracted my attention.

The octagonal font is believed to have been donated to the church in 1408 by the then Lord of the Manor, Thomas Montagu (1388-1428), Earl of Salisbury. Each of its eight sides contains fine bas-relief carvings. Many of them depict saints connected with birth, baptism, and childhood. For example, ther is a carving of St Christopher carrying the young Jesus across a river. Most of the faces on the carvings are in remarkably good condition considering their age and that they were in place long before the iconoclastic activities of Protestants took place. The church’s guidebook mentioned that in the 1540s, the faces of the statues were attacked, but fortunately the workmen, who might well have been men of Ware, responsible for defacing did a “token job”, only defacing the faces of the Virgin and St Margaret because they could be seen by people entering the church. Luckily for us living in the 21st century, these workmen managed to protect what is an attractive piece of church art.