Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 39

September 19, 2024

Mr Postman

Post a letter

In this very small red mail box

Make someone happy

September 18, 2024

William Morris lived here in Oxfordshire but did not make wallpaper

THE NATIONAL TRUST looks after a house in Oxfordshire, which was once owned by William Morris. When I came across this property, Nuffield Place, I was surprised, because I believed that the artist and socialist William Morris (1834-1896) had lived in properties in Hammersmith, Walthamstow, Bexleyheath, and Gloucestershire, but not in Oxfordshire.

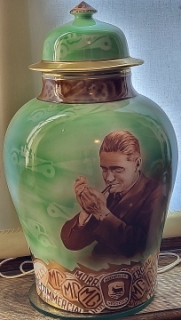

Nuffield Place was the home of another William Morris, who became Baron Nuffield in 1934, and later in 1938, Viscount Nuffield. He lived from 1877 until 1963. At the age of 15, he set up his own bicycle repair business. By 1901, he had a bicycle repair and sales shop on the High Street in Oxford. Two years later, he was manufacturing motorcycles. In 1903, he married Elizabeth Anstey (1884-1959), a seamstress whom he met when both were members of a cycling club. They never produced children.

By 1909, he had set up the Morris Garage in Oxford, and was selling and repairing cars. In 1913, he and his small team of workers had built the first car he had designed. By the time the First World War had begun he had acquired larger premises in Cowley on the edge of Oxford. He was already producing cars that were affordable to the popular market, but during the war, his factory switched to producing products needed for the war effort. While doing this, which was not very profitable, he developed much experience in the techniques of mass-production. One of the many models turned out by the Morris factory was the Morris Oxford. This car has made its mark in India because it was the prototype for the Hindustan Ambassador, which was made in India between 1957 and 2014.

After WW1, Morris began making huge numbers of affordable Morris cars, which sold well. William Morris became incredibly rich. However, he was a modest man and extremely generous. He spent most of his money on philanthropy, particularly in the medical field. Many of the institutions he paid for, which bear the Nuffield name, including Oxford’s Nuffield College, still exist. The number of ways in which he helped are far too numerous to be listed. As a child, he wanted to study medicine, but economic circumstances did not allow that to happen. However, because of all he did to promote healthcare and medical research, he was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1948.

Nuffield Place, the house which William Morris purchased in 1933 and lived in for the rest of his life, was built for the shipping magnate Sir John Bowring Wimble, also chairman of an insurance company, in 1914. It was designed by Oswald Partridge Milne (1881-1968), who worked in the office of Edwin Lutyens between 1902 and 1904. When Sir John died in 1927, his widow sold the house, which was then called ‘Merrow Mount’, to Morris in 1933.

The house is spacious and must have been comfortable to live in, but it is remarkably modest to have been the sole residence of a man as wealthy as the automobile manufacturer William Morris. We were shown around it by a knowledgeable lady, who helped us to appreciate how modest were the lives led by William and Elizabeth Morris. Among the many things that interested me was William Morris’s bedroom. In one corner of it, there is what looks like a wardrobe. However, when the doors are open, it can be seen to be filled with tools and a workbench. Morris had his own workshop in his bedroom. His wife continued her seamstress skills, and many chairs were covered with textiles she had worked on. The house contains many books on a variety of subjects including history and politics. One bookshelf is filled with medical treatises. Morris, although he never became a doctor, was interested in reading about medicine.

Nuffield Place contains an iron lung machine, such as was used to help sufferers of poliomyelitis to breathe. On learning that there was a shortage of these machines in Britain, Morris used his factories to produce many of them to distribute to hospitals that needed them. The model he helped design, and his factories manufactured, has some curious details. The handles that were used to adjust the apparatus look just like car door handles. And some other components on the iron lung look very much like the hinges of car doors. These iron lungs were a valuable contribution to the treatment of diseases such as polio.

I could describe much more of what we saw at Nuffield Place, but it would be better if you visit the it. Lovers of gardens will also enjoy visiting this house owned by a William Morris, who did not design flowery wallpapers.

September 17, 2024

Is SITE-SPECIFIC art really such a new idea

RECENTLY, WE HAVE viewed two exhibitions, one in Cambridge and the other in Dulwich (South London), which contain site specific works. The website of New York’s Guggenheim Museum (www.guggenheim.org/artwork/movement/s...) defines site specific art as follows:

“Site-specific or Environmental art refers to an artist’s intervention in a specific locale, creating a work that is integrated with its surroundings and that explores its relationship to the topography of its locale, whether indoors or out, urban, desert, marine, or otherwise … No matter which approach an artist takes, Site-specific art is meant to become part of its locale, and to restructure the viewer’s conceptual and perceptual experience of that locale through the artist’s intervention.”

It seems that site-specific art is the name given to a relatively recent artistic trend or movement.

By Megan Rooney

In Cambridge’s Kettle’s Yard, we saw a room whose walls were entirely covered by paintings created by the artist Megan Rooney. She spent several days painting on the walls. When the exhibition is over (on the 6th of October 2024), the walls will be whitewashed, and her site-specific creation made especially for the room will disappear. At Dulwich Picture Gallery, there is a room whose walls have been decorated by the Japanese artist Yoshida Ayomi. Her beautiful evocation of cherry blossom was made specially for the room in which it can be seen. Her site-specific work will be removed when the exhibition is over on the 3rd of November 2024. These two artworks, like those of the artist Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935–2020), who temporarily covered buildings with sheets of various materials, are classed as site-specific. Currently, it seems to me that site-specific artworks are usually temporary in nature.

Michelangelo covered the walls and ceilings of Rome’s Sistine Chapel with paintings. Likewise, the ceiling in the Residenz, a palace in Würzburg, were covered by paintings created by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and his sons specially for the room. Should these examples and many others like them be considered ‘site-specific’ art, or is the term only to be applied to creations of artists made during the 20th and 21st centuries? Probably not, because those who commissioned frescoes and murals for rooms many centuries ago, usually hoped that the artworks would outlast them and their creators. The artists who have made site specific art currently and in the recent past do not always expect them to last for as long as those made several centuries ago.

September 16, 2024

Opera performed by puppets in a restaurant in Chicago

When I was eleven years old, we stayed in Chicago (Illinois) for three months.

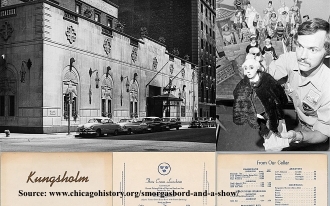

One evening, our parents took us to something wonderful. It was at the Kungsholm Restaurant in the centre of Chicago. After dining at its self-service Danish ‘smörgåsbord’ (a kind of buffet), we were ushered into a small theatre. The lights went down, and the curtains of a small stage opened. Then we watched a whole opera performed by puppets operated by people out of sight below the stage. I do not recall which opera we watched, but I do remember at the end of the performance, the puppeteers raised their heads above the stage. As my eyes had become used to the short puppets during the opera, the heads of the puppeteers looked gigantic.

For more information about Kungsholm, see:

September 15, 2024

A hidden oasis close to Piccadilly in London’s Mayfair

WE VISIT DOVER Street in London’s Mayfair frequently to view exhibitions at the commercial art galleries along it. Laid out in the late 17th century, the street is named after Henry Jermyn (c1636-1708), 1st Baron Dover, who was a member of the syndicate that developed the area in which it is located.

Despite having walked along this street countless numbers of times, it was only this September (2024) that we spotted the entrance to a narrow alley way on the west side of the street between numbers 41 and 43. The alley is called Dover Yard. The first 12 yards of this passageway are covered by a high barrel vaulted, brick-lined ceiling. Then, after a short stretch open to the sky, one enters a wide yard made attractive with plenty of plants.

The yard itself is surrounded by modern buildings. In the 1970s, the yard, which has existed since the 18th century, was bought by developers and used as service area and parking lot (www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/londons-alleys-dover-yard-w1-64590/). It was redeveloped recently, and is now flanked by the elegantly designed Nightingale coffee bar and restaurant (part of 1 Hotel Mayfair) on the north side, and Dovetail, a Michelin-starred restaurant, faces it. West of the wide yard, there is another narrow alleyway leading to Berkely Street. It has become a peaceful, almost hidden oasis in the heart of a busy part of Mayfair not far from Piccadilly.

As is often the case when revisiting places we thought we knew well in London, we come across places like Dover Yard, which we have passed often but never noticed. Although we did not try it, the Nightingale looks like it would be a very pleasant place to stop for refreshment.

September 14, 2024

British weather

Clouds grey and white

Always very unpredictable

That’s British weather

September 13, 2024

Discovering a garden in London’s Piccadilly

WE HAVE WALKED along Jermyn Street and visited Christopher Wren’s church of St James (Piccadilly) innumerable times without being aware that right next to both, there is an attractive public garden. It was only today (the 10th of September 2024) that we first became aware of its existence. The place in question is Southwood Garden. It lies west of the church and along part of the north side of Jermyn Street.

For 200 years the plot to the west of the church was used as a burial ground. At the end of WW2, the newspaper proprietor and Labour politician Viscount Southwood (1873-1946) paid to have the burial ground made into a garden to commemorate the bravery and courage of the people of London. The garden was opened in 1946 by Queen Mary (the wife of King George V).

The garden is approached by short flights of steps, which flank a small pond with a fountain. The pond is flanked by bronze sculptures of two children, each riding on the backs of a pair of dolphins. There are two other sculpted children, one on each side of the steps. At the top of the steps, there is a stone inscribed with “Viscount Southwood”. The few steps lead to a paved area, at the back of which there is an inscribed plaque explaining that Viscount Southwood provided the garden that stands on what had been a bomb-damaged burial ground. Another couple of steps at the southeast corner of the paved area lead up to the well-tended grassy, rectangular garden.

In addition to the sculptures of children astride dolphins, there is another bronze sculpture in the garden. It depicts a standing woman holding some leaves in her right hand. It is called “Peace”. All the sculptures at Southwood Garden were made by the English sculptor Alfred Frank Hardiman (1891-1949).

How could we have missed this delightful garden? There are two possible reasons. First, you cannot see it from Jermyn Street. Second, the fountain and entrance to the gardens are almost hidden behind the food stalls, which are set up during the day in the paved courtyard on the north side of the church. Well, I am pleased that we have ‘discovered’ it at last.

September 12, 2024

Modernism in Ghana and India in a museum in London’s South Kensington

UNTIL THE 22nd OF SEPTEMBER 2024, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London’s South Kensington is hosting an exhibition called “Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence”. It focuses on two countries: Ghana and India. It was the exhibits relating to India that interested me most, although those connected with Ghana were also intriguing.

The Royal Institute of British Architects describes Modernism as follows:

“Rejecting ornament and embracing minimalism, Modernism became the single most important new style or philosophy of architecture and design of the 20th century. It was associated with an analytical approach to the function of buildings, a strictly rational use of (often new) materials, structural innovation and the elimination of ornament.” (www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/modernism).

Modernism began both in the USA and Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Its better-known pioneering exponents include Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, Maxwell Fry, Louis Kahn, and Eero Saarinen. The Modernist architects, like the abstract painters of the early 20th century, broke with traditional approaches to form and style.

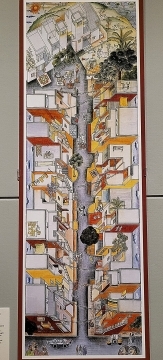

On the 15th of August 1947, India became independent. The country was no longer ruled by foreigners. Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) became India’s first Prime Minister, a position he retained until his death. His vision for India was for it to shake off the shackles of the past (both colonial and traditional) to become a modern state. This extended to architecture in his new India. He invited Modernist architects including Le Corbusier and his cousin Perre Jeanneret to design a new city in the Punjab (following the loss of Lahore to Pakistan): Chandigarh. This is illustrated well in the V&A exhibition. Le Corbusier wanted to create his ideal of a city, which included forbidding street markets and cows to wandering in its streets. His pupil and collaborator, Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, who died in 2023, had a more human approach to architecture. Having seen some of his buildings, notably in Ahmedabad and Bangalore, I would say that Doshi developed an architectural opus, which might be loosely described as ‘user-friendly Corbusier’. Incidentally, Doshi was also taught by Louis Kahn, who worked in India, notably in Ahmedabad.

A label in the exhibition noted that in 1959, at a conference about national identity in Indian architecture, Nehru urged Indian architects not to be “imprisoned by tradition”, but to experiment as had been done at Chandigarh (built between 1951 and 1956). Examples of this experimentation can be seen in the exhibition.

Naturally, since Nehru’s death, there have been many changes in India. I notice new changes every time we make our annual trips to the country. Nehru’s vision of a secular India has been replaced by a different vision in the minds of the leaders of the present Indian Government. Modernism’s internationalist aspects, which attracted Nehru and some of his successors, appear to have lost their appeal currently in India.

Immediately after gaining independence, both Ghana and India favoured Modernism in architecture. The exhibition at the V&A shows that even before independence, architects (almost all European) in Ghana had been building in the Modernist style, but specially adapted to cope with intense heat and high humidity. Ghana’s first leader, Kwame Nkrumah, encouraged the continuation of this architectural style. The exhibition includes a fascinating video about this. In India, Modernism seems to have been introduced post-independence. Both leaders wanted to project visions of a emerging modern countries, freed from the constraints of colonialism. Yet both promoted an architectural style developed largely by architects who came from countries that had had colonies in Asia and Africa.

Before ending this piece, I must not forget to mention two exhibits, which caricatured the great British colonial architect, Edwin Lutyens, who was certainly not a Modernist. One of them is a model of Lutyens’s head which has been combined with a model of one of his imperial buildings in New Delhi. The other, which is painted in the style of a Mughal miniature, shows Lutyens offering a model of the (British) Viceroy’s House (in New Delhi) to the Viceroy.

The exhibition was fascinating. Despite its rather obscure title, a good number of viewers were there during the Monday mid-afternoon when we visited it.

September 11, 2024

Three hares or rabbits sharing three ears between them in a church in Buckinghamshire

WE HAVE COME ACROSS this type of curious motif once before in the parish church at Long Melford (Suffolk), and recently (September 2024) in the parish church at Long Crendon (Buckinghamshire). The motif consists of three hares (or rabbits) in a circle and joined by their ears which form a triangle at the centre of the design. Each creature appears to have two ears, but between them, they share only three ears. At Long Melford, this image can be seen in a small piece of mediaeval stained glass in a window on the north side of the church. At Long Crendon, it can be seen on a small 14th century tile close to the high altar.

According to the guidebook we obtained in the church at Long Crendon, the three hare/rabbit motif is only seen in a few places in Britain (including 12 of the Stannary villages in Devon and Cornwall, Long Melford, Lavenham, and Chester Cathedral). Also, it stated that it can be seen:

“… in a few places stretching from China to Europe along the Silk Road.”

Well, this got me very interested, and I did a little research on the Internet. Soon, I came across a website, “Three Hares Project” (www.chrischapmanphotography.co.uk/hares/page7.htm). This site contains a mine of information including a map showing where the motif has been found along the Silk Route and other places.

The earliest examples that have been found are on the ceilings of Buddhist caves near Dunhuang in China. They been dated as having been placed there between 581 AD and 907 AD. The three hares have also been found on a late 12th or early 13th century Iranian tray made of brass inlaid with copper. Another example was found painted on the ceiling panel that once used to adorn an 18th century German synagogue. The authors of the website noted:

“The three hares are also found in glass and ceramic wares from the Islamic world.”

So, it appears that the motif that we have seen in churches was not confined to Christian usage.

As to the meaning of the three hares/rabbits motif, the website offered the following:

“… as yet, we have not come across a contemporary written record of its meaning … The hare is strongly represented in world mythology and from ancient times has had divine associations. Its elusiveness and unusual behaviour, particularly at night, have reinforced its reputation as a magical creature. The hare was believed to have mystical links to the female cycle and to the moon which governed it.”

What it meant to Christians, who placed the motif in their churches, was suggested on the website. It said that the ancients believed that the hare was hermaphroditic, and could give birth to its offspring without need for copulation. In relation to this, the learned Thomas Browne (1605-1682) wrote in 1646 in his “Pseudodoxia Epidemica”:

“THE double sex of single Hares, or that every Hare is both male and female, beside the vulgar opinion, was the affirmative of Archelaus, of Plutarch, Philostratus, and many more. Of the same belief have been the Jewish Rabbins: The same is likewise confirmed from the Hebrew word; which, as though there were no single males of that kind, hath only obtained a name of the feminine gender.” (https://penelope.uchicago.edu/pseudodoxia/pseudo317.html).

This belief might have led Christians of old to compare the hare to the Virgin Mary and the birth of her well-known son.

Another less likely possibility is that the three creatures have something to do with representing the Holy Trinity.

Whatever its meaning, I find the motif of three hares sharing three ears almost as fascinating as the eagle with one body and two heads (the double-headed eagle, such as seen, for example, on the flag of Albania and the crest of the Indian State of Karnataka).

September 10, 2024

A circular church close to London’s Leicester Square

I HAVE WRITTEN about this place before, but because it is so lovely, I will write about it again. Located in Leicester Place, which runs north from Leicester Square, it is the francophone Roman Catholic church of Notre Dame de France. Constructed earlier than the mid-19th century, it was originally a visitor attraction known as Burford’s Panorama. In 1865, the French Church bought the building and with the help of the architect Louis-Auguste Boileau (1812-1896), it was converted into a church. He retained the circular plan of the former Panorama and kept its dome. It was the first church in London to incorporate cast-iron structural elements. Badly damaged during WW2, it was rebuilt between 1953 and 1955 under the supervision of the Greek born architect Hector Corfiato (1892-1963).

By Timur D’Vatz

The church is a peaceful haven in a busy district of London. During the day, there are usually several homeless people lying asleep on the pews. Until our recent visit in August 2024, we usually made a beeline for a side chapel on the north side of the church. The walls of this small chapel are covered with coloured line drawings by Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Depicting the Annunciation, Crucifixion and Assumption, Cocteau completed them in a week during 1962. In addition to the walls, Cocteau painted a wooden panel to cover the front of the chapels altar. This has been removed because it covered a mosaic created in 1954 by the Russian born artist Boris Anrep (1883-1969), who is best known for his mosaics on the floor of the National Gallery. The wooden panel can now be viewed in an alcove next to the chapel. After we had paid homage to the Cocteau drawings, we decided to look at some of the other artwork in the church.

There is a large tapestry above the high altar. It is based on the theme ‘Paradise on earth’, and was created in 19 by Dom Robert de Chaumac (1907-1977), a Benedictine monk from France. He was a friend of Jean Cocteau. Between 1948 and 1958, Dom Robert lived at Buckfast Abbey in Devon. The tapestry was woven in France in 1954. High up on the southeast wall of the church there is an attractive painting depicting the Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt. It was painted in 2016 by Timur D’Vatz, who was born in Moscow (Russia) in 1968. Between 1983 and 1987, he studied art at the Republican College of Art, Tashkent, and between 1993 and 1996, he studied at London’s Royal College of Art. He arrived in London from Moscow in 1992. In 2004, he acquired a studio in France.

Two polygonal incised stone ambos (lecterns) can be seen, one on each side of the high altar. The one on the north side has carvings and names of New Testament figures, and that on the south has Old Testament names and figures. I have not yet found out who designed or made these elegant geometric items. Likewise, I do not know who created the illustrated tiles that can be found at each of the Stations of the Cross.

The façade of the church is worth examining. High above the entrance to the church, there is a large carved stone bas-relief depicting Our Lady of Mercy. It was created in 1953 by the French sculptor Georges Saupique (1889-1961). Below this and flanking the entrance, there are two attractively carved pillars with eight scenes from the life of Mary. These were carved by students from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (France).