Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 40

September 10, 2024

A circular church close to London’s Leicester Square

I HAVE WRITTEN about this place before, but because it is so lovely, I will write about it again. Located in Leicester Place, which runs north from Leicester Square, it is the francophone Roman Catholic church of Notre Dame de France. Constructed earlier than the mid-19th century, it was originally a visitor attraction known as Burford’s Panorama. In 1865, the French Church bought the building and with the help of the architect Louis-Auguste Boileau (1812-1896), it was converted into a church. He retained the circular plan of the former Panorama and kept its dome. It was the first church in London to incorporate cast-iron structural elements. Badly damaged during WW2, it was rebuilt between 1953 and 1955 under the supervision of the Greek born architect Hector Corfiato (1892-1963).

By Timur D’Vatz

The church is a peaceful haven in a busy district of London. During the day, there are usually several homeless people lying asleep on the pews. Until our recent visit in August 2024, we usually made a beeline for a side chapel on the north side of the church. The walls of this small chapel are covered with coloured line drawings by Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). Depicting the Annunciation, Crucifixion and Assumption, Cocteau completed them in a week during 1962. In addition to the walls, Cocteau painted a wooden panel to cover the front of the chapels altar. This has been removed because it covered a mosaic created in 1954 by the Russian born artist Boris Anrep (1883-1969), who is best known for his mosaics on the floor of the National Gallery. The wooden panel can now be viewed in an alcove next to the chapel. After we had paid homage to the Cocteau drawings, we decided to look at some of the other artwork in the church.

There is a large tapestry above the high altar. It is based on the theme ‘Paradise on earth’, and was created in 19 by Dom Robert de Chaumac (1907-1977), a Benedictine monk from France. He was a friend of Jean Cocteau. Between 1948 and 1958, Dom Robert lived at Buckfast Abbey in Devon. The tapestry was woven in France in 1954. High up on the southeast wall of the church there is an attractive painting depicting the Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt. It was painted in 2016 by Timur D’Vatz, who was born in Moscow (Russia) in 1968. Between 1983 and 1987, he studied art at the Republican College of Art, Tashkent, and between 1993 and 1996, he studied at London’s Royal College of Art. He arrived in London from Moscow in 1992. In 2004, he acquired a studio in France.

Two polygonal incised stone ambos (lecterns) can be seen, one on each side of the high altar. The one on the north side has carvings and names of New Testament figures, and that on the south has Old Testament names and figures. I have not yet found out who designed or made these elegant geometric items. Likewise, I do not know who created the illustrated tiles that can be found at each of the Stations of the Cross.

The façade of the church is worth examining. High above the entrance to the church, there is a large carved stone bas-relief depicting Our Lady of Mercy. It was created in 1953 by the French sculptor Georges Saupique (1889-1961). Below this and flanking the entrance, there are two attractively carved pillars with eight scenes from the life of Mary. These were carved by students from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (France).

September 9, 2024

Some old baggage discovered in an attic and a Roman toga

WHEN MY FATHER sold our family home in Hampstead Garden Suburb in the early 1990s, he gave some of his unwanted possessions to some neighbours, who still live opposite. They stored much of it in their attic. Recently, a plumbing problem required them to empty the attic. Soon after this, we paid them a visit as we had not seen them since before the start of the covid19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns. Amongst the stuff they removed from their attic, they found a sturdy, brown leather suitcase in a well-worn canvas protective covering. The covering was stencilled with the letters ‘BSY’, these being my father’s initials.

The canvas case bears an oval label, which was provided by the “Holland-Afrikalijn”. It states that the suitcase was “For the cabin” and the name of the ship’s destination was “Southampton”. The ship carrying this case was the “Jagersfontein”, and the label bears the date “3/9/55”, There is another torn label, which was issued by South African Railways and what is left of it is “T Elizabeth”, which probably was “Port Elizabeth” before it was torn. This suggests that the case must have travelled to and/or from Port Elizabeth by rail. A third label, which is circular and was stuck on by the shipping company bears a large capital “Y”.

By September 1955, I was three years (and a few months) old. That year, my parents, who were born in South Africa, took me from London, where we lived, to be shown to family and friends in that country. I remember almost nothing of that visit apart from two things. One of them was getting my small foot caught in the groove of the tram-like track of a mobile dockside crane. The other thing was being afraid of the cacti in a greenhouse in a park in Port Elizabeth, the city where my father’s sister and his mother resided.

I know that we also visited King Williams Town, where many of my mother’s family lived. This visit was recorded in a 1955 issue of the town’s “Cape Mercury” newspaper. I discovered it while I was researching information about my mother’s grandmother, who lived in the town. The newspaper article, which is full of small inaccuracies, described me as being “… an adorable little son, aged three …”.

The Jagersfontein has an interesting history (http://ssmaritime.com/fontein-ships-1.htm). Built in Danzig (Germany) in 1939 and given another name, it was badly damaged during WW2, and it sunk. In 1947, she was recovered from the sea, towed to Holland, and refurbished by the Dutch. In September 1947, she began sailing again, as a passenger-cargo liner.

During the voyage from Southampton to South Africa, I crossed the Equator for the first time in my life. My mother told me that when the ship carrying us crossed the Line, a fancy-dress party was held for the children onboard. Some of the parents knew that this would happen and had come prepared with fancy-dress costumes for their children. However, my mother was unaware that this would happen. Being a creative person, she took some of the white bed linen from our cabin, and fashioned a Roman toga for me to wear at the party.

My mother died 44 years ago. Only a few days before we saw the suitcase at our old neighbours’ home, I was rummaging through some photographs that I had not seen since her death. It shows me in my rapidly fashioned bedsheet toga, standing between two larger children dressed up to depict Belisha beacons (that mark so-called ‘zebra’ pedestrian crossings). A small cloth with black and white stripes, representing a zebra crossing, separated the two beacons. Behind the three of us are some adults, whom I cannot recognise.

Empty, the leather case, which looks almost new, weighs 6.3 kilogrammes (13.9 lb). In 1955, passengers travelling by ships such as the Jagersfontein did not need to worry about the weight of their luggage. There were plenty of porters to carry it. We have been given the suitcase, which our daughter is keen to have because it is a family heirloom with sentimental value. Along with the photograph and the newspaper cutting, the case is a wonderful reminder of my first ever travel adventure.

September 8, 2024

West of London but not an attraction for tourists

OVER THE YEARS. We have made many visits to Slough, a town in Berkshire, just west of Heathrow Airport. It would usually not figure on tourists’ lists of places that they feel they must see. And there is little in Slough that would entice people to visit the place. Yet, since the early 1970s, we have visited there often.

My PhD supervisor, Robert Harkness, and his wife, Margaret, lived in the countryside not far from Slough. They used to travel between Slough and Paddington stations when they were travelling to and from University College London (‘UCL’). While I was studying with them, they became my close friends. Until they died in the early years of this century, I, and then later my wife and our daughter, often spent weekends in their large Victorian home, Margaret, who played the violin, was involved with the Slough Philharmonic Orchestra (Slough Philharmonic Society). For many years, she not only played in the second violin section but also, she was the orchestra’s honorary accountant. We were often invited to the orchestra’s concerts, many of which were held in concert halls in Slough. A few of the concerts were held in Slough’s ‘posh’ neighbour Eton.

Because Robert and Margaret lived near Slough and we visited them often, we hired a storage unit (‘godown’) in Slough. We could combine visiting our friends with making trips to add things to our storage place. Sadly, Robert and Margaret are now no more than fond memories. However, our storage locker remains in Slough. So, visits to the town continue.

Recently, the company that stores our stuff moved from the edge of Slough to a place closer to the centre. It has a good car park and is close to a wonderful range of food shops. Slough has many inhabitants whose ancestors hail from the Indian Subcontinent and a sizeable Polish population. On the outskirts of Slough, there is at least one large Polish sporting/country club. Near our newly located storage place, there are two well-stocked Polish food supermarkets, which sell many products including things that would not be found at the nearby halal food shops and eateries. In addition to food shops catering for people of Indian and Pakistani origins, there are gift shops where decorated Hindu idols can be bought. There is also a jewellery store whose gold and diamond-studded items are just like what I have seen in India.

Drab as Slough undoubtedly is, the ethnic mix of its inhabitants add a welcome touch of colour and exoticism to the place. Having said that, I am not sure that I would recommend going there unless you have a reason to do so.

September 7, 2024

Tablet the cat

September 6, 2024

Stafford Cripps, Mahatma Gandhi, and an art gallery in London’s Islington

JUST OVER SEVEN years ago, I bought a book, which I put on a bookshelf without reading it, and then forgot about it. This September (2024) I found it whilst sorting through our book collection. It is a biography of the British politician Stafford Cripps (1889-1952), who visited India in March 1942. Winston Churchill had sent him there to negotiate with leading Indian Nationalists (including Gandhi, Jinnah, and Nehru) to keep them loyal to the British war effort in exchange for self-government when WW2 was over. It was up to Cripps, then a Labour politician, to formulate the proposed deal. The mission was not a success because Churchill thought that Cripps had offered the Indians too much, and the Indians thought his offer was not enough: they wanted independence immediately.

There have been many books written about Stafford Cripps. The one I found in my collection, “Stafford Cripps. A biography”, was published in 1949, when Cripps was still alive. When I looked at the book after ‘discovering’ it, what surprised me was the name of its author: Eric Estorick.

Until I looked at the book today (3rd of September 2024), I had only associated the name Estorick with a fine museum of 20th century Italian art – The Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art. This is housed within Northampton Lodge, a Georgian building which was once the home and offices of the architect Sir Basil Spence (1907-1976), who was born in Bombay. This is in Canonbury, which is just north of Islington. The collection was established by the American Eric Estorick (1913-1993) and his German-born English wife Salome (1920–1989) after WW2.

Eric Estorick was none other than the author of the biography of Cripps, which I ‘unearthed’ today. Born in Brooklyn (NY), son of Jewish emigrés from the Russian Empire, he was awarded a PhD in sociology at New York University. In 1947, he married Salome (née Dessau), who was an artist. Eric’s interest in art began before that when he met the American photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). The Estoricks began collecting art soon after the end of WW2. During their honeymoon, the Estoricks were introduced to the works of the Italian Futurists. The Collection contains several good examples of their works. In 1960, Eric opened the Grosvenor Gallery in London’s Davies Street. His first exhibition was a display of modern sculpture. It was in his gallery that my mother exhibited some of her sculptures in 1965, in an exhibition called “Fifty Years of Sculpture. Some aspects 1914-1964”. She must have been introduced to Eric at the time.

Apart from his interests in art, Eric Estorick was a prolific author. In addition to writing three books about Stafford Cripps, he wrote others about politics as well as art. One of his books, which was published privately, was a history of the Marks and Spencer firm, in which he worked for some time. It was in that company that Salome Estorick had worked. Marks and Spencer had been a customer of her father’s textile manufacturing firm.

Having found my copy of Estorick’s book and skimmed its contents, I will not be putting it into our storage unit as I had originally intended, but will begin reading it soon.

September 5, 2024

Caught in time in west Buckinghamshire

DUE TO BE DEMOLISHED in 1900, the newly established National Trust (founded in 1895) saved it from this terrible fate that year. The building is a long, narrow half-timbered, brick and wattle structure in the attractive village of Long Crendon in the west of Buckinghamshire. Built sometime between the 14th and 15th century, it served as the manorial courthouse.

Meetings of the manorial court of Long Crendon are believed to have begun before the 13th century. Until 1233, they were held in the lord of the manor’s house, which was demolished that year. In 1275, the manor was divided equally among three female heirs, and courts were held in the farmhouses of their families. By 1558, the courts of the three lords of the manors combined, and it must have been around this time that the courthouse began being used for judicial procedures. The building was not only used by the court but also as a facility for the poor. By the 19th century, it was used by one family to store wool. Some historians question this. In Victorian times the courtroom was used as a Sunday school and a place where occasional public lectures were given.

In 1900, the National Trust purchased the venerable edifice and began repairing it to keep it standing. The Arts and Crafts architect and designer Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) and his wife lived in the courthouse. They used to invite groups of apprentices from London for arts-based holidays lasting a fortnight. In 1902, the Ashbees, whose bohemian activities disturbed the locals, left for Chipping Camden where they established the Guild of Handicrafts. In 1918, Ashbee was sent to Jerusalem as civic adviser to the British Administration for Palestine. In 1937, the courthouse became used as a clinic by the area’s District Nurse. This continued after the NHS was established in 1948. The courtroom then served as a Welfare Clinic.

Between 1985 and 1987, the building was intensively restored. Now, the long room, which occupies most of the upper floor, and was once the court room, is now a village museum. It is reached by a steep flight of wooden stairs. The upper rooms are the only part of the building open to the public. The long courtroom has a timber floor made with irregularly shaped planks. The arched ceiling is supported by massive timber crossbeams. Each one differs in shape from the others. Various exhibits and boards with historic photographs line the walls of this otherwise empty room, in which long ago trials were held.

We visited Long Crendon to see the courthouse. However, many other buildings in this village are incredibly picturesque and well-worth exploring.

September 4, 2024

About Space at an exhibition in a gallery in south London’s Bermondsey

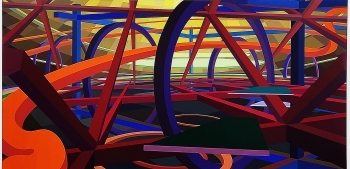

THE TROUBLE WITH temporary exhibitions is that they come to an end. So, if you miss it, you might never see the same works of art together again. I am very pleased that we just managed to catch a superb exhibition at the White Cube gallery in Bermondsey on its final day (1st of September 2024). Called “About Space”, it is a show of paintings by an artist, of whom I had not come across before: Al Held (1928-2005).

Al Held was born in Brooklyn (NYC). His Jewish family was impoverished during the Great Depression and had to survive on welfare payments. Having served in the US forces during WW2, he was eligible (under the terms of the GI Bill) for financial assistance with his education after the war. He studied painting first in New York City, and then in Paris (France). Over the years, he explored different styles of painting, and after exhibiting at major art museums in the USA, his work began to be shown at prestigious galleries outside the USA.

The paintings on display at the White Cube date from the 1960s onwards. Many of them are huge, dwarfing the viewers. A few are smaller. All of them are visually spectacular. Although two-dimensional, they depict complex three-dimensional abstract imaginary constructions. Viewing these amazing compositions is like looking through a huge window at the kind of fantastical geometric abstracted landscapes that might now be produced by digital means. As the title of the exhibition implies, Held’s paintings are literally about space. Painted with precision, these compositions explode with energy.

I am glad that we did not miss the exciting experience of seeing these paintings created by a man, who had shown no interest in art until he left the US Navy in 1947. It was his friend the artist Nicholas Krushenick (1929 – 1999), who inspired him to take up art, and I am very pleased that he did.

September 3, 2024

From the Dominican Republic to South London via the USA

FIRELEI BÁEZ WAS born in the Dominican Republic in 1981. She studied art in the USA, where she now lives and works. The South London Gallery (‘SLG’) in South London’s Peckham district is hosting her first solo exhibition in the UK. The show continues until the 8th of September 2024. The exhibition is distributed between the main gallery building and a converted fire station, which is a few yards away.

The large exhibition space in the main building is occupied by a wonderful immersive installation. The viewer walks beneath a huge blue canopy with multiple small oval holes suspended from the ceiling. Light filters through the material of the canopy producing the effect of sunlight dappled by leaves of trees, creating the feeling that one is walking in a forest. Recordings of bird sounds enhance this illusion. On the walls of the room there are large, boldly coloured aluminium cut outs, representing silhouettes of Ciguapas – figures from the folklore of the Dominican Republic.

In the converted former fire station, there are yet more works by Firelei Baez. On the ground floor, there are huge floor-to-ceiling, extremely colourful abstract paintings. The artist’s idea is to immerse the viewer in an excitingly vibrant sea of colours. The first floor has two galleries. In one, there are large, richly coloured silhouettes depicting Ciguapas. In the other, there are many pages from books, which the artist has transformed by overlaying parts of each of them with paint or ink. In doing this, she provides the viewer with alternative versions of what was originally on the page before she added her artwork. Although libraries and book-collectors might well object to extracting pages from books and then painting over them, the effects Firelei produced are both witty and attractive. In addition, they make you think twice about what was originally on the page.

For a north Londoner like me, Peckham seems to be a distant part of the world, but actually it is not to difficult to reach it by public transport. And many of the exhibitions we have viewed at SLG, including the one described above, makes the trip to Peckham well worth making.

September 2, 2024

Do you have middle name(s) and do they embarrass you?

FREQUENTLY PEOPLE HAVE more than one name other than their family name (surname). For example, I am Adam Robert Yamey. My father, an economist, had suggested that I should be called Adam Smith Yamey to commemorate the famous early economist Adam Smith. I would not have minded that, but my mother was not happy with the idea, so I learned much later. More famous examples include the painter John Mallord William Turner and the politicians Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. My PhD supervisor at University College London had even more ‘middle’ names. He was Robert Douglas Mignon Innes Kerr Harkness. Often, the middle names are those in memory of ancestors. Such must have the case for Robert Harkness, as well as for Churchill and Gandhi.

Photo source: wikipedia

My mother hated her middle name. It was Bertha. I often wondered why she had been given that name. When I began researching the history of my mother’s family, I discovered why she might have had that name on her birth certificate. Her mother had a cousin called Bertha. The reason my mother disliked this name was that during WW1, the Imperial German Army had a large canon, the 42 centimetre kurze Marinekanone 14 L/12, which was manufactured by the Krupp company in Essen (Germany). What upset my mother was that the artillery piece was commonly known by its nickname ‘Big Bertha’. My mother was born only two years after WW1 ended, and the Big Bertha must have been reasonably well-known when she started going to school. You can imagine how much teasing she got when the other pupils discovered her middle name.

Do you have a middle name (or several middle names) and does it (or they) embarrass you?

September 1, 2024

The white cliffs

These steep white rocks

Fall into the briny channel

They’re England’s sharp edge

Photograph taken at Folkestone (Kent)