Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 42

August 20, 2024

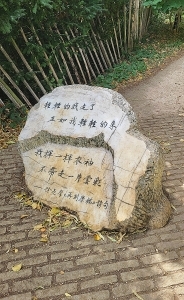

A stone with Chinese characters in a garden in Cambridge

WHEN RABINDRANATH TAGORE (1861-1941) visited China in 1924, he gave a series of lectures in English, which were translated for the Chinese audiences by the talented young poet Xu Zhimo (1897-1931). During a visit to Cambridge (UK) in August 2024, in several shop windows I noticed a book called “Xu Zhimo Cambridge & China” by Zilan Wang. Even though Cambridge has many students and tourists from China, I wondered about it.

Xu Zhimo was born in Haining (China). He studied law in Beijing, then in 1918 travelled to the USA, where he studied for, and was awarded a degree at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. After starting a degree at Columbia University in New York City, he left the USA because he could no longer stand the place. He then travelled to the UK, where he first studied at the London School of Economics, and then at Kings College, Cambridge. It was in Cambridge that he became deeply attracted to poetry, and began writing it. In 1922, he returned to China, where he became an important figure in China’s modern poetry movement. He was a believer in ‘art for art’s sake’ rather than the (Chinese) Communists’ belief that art should serve politics.

When Tagore came to China, the country was in turmoil: there was fighting between rival warlords and the risk of an invasion by the Japanese was great. Xu Zhimo served as one of his oral interpreters, translating Rabindranath’s romantic (English) language into vernacular Chinese. Tagore did not rate his visit to China a great success. He was met with some hostility as Huan Zhao explained in the introduction to an article entitled “Interpreting for Tagore in 1920s China: a study from the perspective of Said’s traveling theory” (Perspectives, Volume 29, 2021 – Issue 4):

“During Tagore’s visit, his initial perceptions of welcome were transformed dramatically into a feeling of rejection, resulting in an unpleasant sojourn. After forty-odd days, Tagore left China, disconsolate, with his mission unaccomplished. Exactly what happened remains unclear. The introductory flyleaf of Talks in China claims his poor reception had much to do with ‘organized hostility from the members of the Communist Party and was labeled as a reactionary and ideologically dangerous.’ Others maintain that Xu, as Tagore’s interpreter, should shoulder much of the responsibility for the visit’s outcome – that Xu’s efforts to enhance his own fame while welcoming Tagore effaced Tagore’s purposes and ideas”

And in the author’s conclusion, the following was written:

“In 1920s China, Tagore’s lectures and Xu’s interpretations faced strong resistance from Chinese intellectuals who sought radical social reform. This resistance interrupted Tagore’s visit and inflicted lasting anguish on his interpreter Xu Zhimo. Although challenged by critics, Tagore’s lectures continued to influence Chinese philosophers, thanks in large part to Xu’s unyielding efforts to expand and explain Tagore’s lectures.”

Xu Zhimo was killed in an air crash in November 1931.

On our recent visit to Kings College in Cambridge, we stopped to look at a large stone on which Chinese writing characters are inscribed. We had passed it on previous visits to the city, but had not investigated it. This time, we noticed a short path leading from the stone into a circular enclosure surrounded bushes and trees. The path is lined with rectangular paving stones on which some lines of a poem by Xu Zhimo is carved. Alternate stones are in Chinese, the others are in English. The words are from Xu’s poem “再别康桥” (Zài Bié Kāngqiáo, which means ‘Taking Leave of Cambridge once more”), which he wrote in 1928. The enclosed area has a small bench upon which we sat, watching a continuous stream of Chinese people visiting the memorial, stopping to look at it respectfully.

August 19, 2024

Georgian lamps in images of Manchester by LS Lowry

THE ARTIST LS LOWRY (1887-1976) often gives prominence to street lamps in his paintings and drawings. In a few of his pictures, he includes overthrow lamps. These are lamps held by semicircular cast iron hoops above gateways or entrances.

An overthrow lamp drawn by Lowry

In his book “Lowry’s Lamps”, Richard Mayson noted that overthrow lamps were Georgian in origin and are more likely to be found in front of elegant houses Bath or London than in Manchester, where Lowry created most of his compositions. Manchester did not have many of these smart dwellings. The few examples of this kind of lamp in Manchester were usually to be found at public spaces, such as parks and cemeteries.

Mayson noted that Kensington Square in London is rich in these lamps. Today, I visited the Square, and found that what he wrote is accurate. By the way, his book is an excellent appreciation of Lowry and his work.

August 18, 2024

History scratched in stone in a village in Hertfordshire

HISTORY SCRATCHED ON A WALL IN HERTFORDSHIRE

I HAVE WRITTEN ABOUT this before, but because I found it so interesting I will write about it again. In August 2024, we revisited the picturesque village of Ashwell in Hertfordshire on our way between London and Cambridge. Apart from being an extremely attractive place, its parish church of St Mary ccontains an intriguing image scratched into the internal surface of the north wall of the bell tower.

The image is a drawing of London’s old St Paul’s Cathedral, which was destroyed during the Great Fire of London (1666). By comparing this picture with other pre-1666 drawings of the old cathedral, it can be seen to be an accurate depiction of the long since destroyed edifice. It is likely that the drawing in Ashwell was scratched into the wall sometime before 1930s, when the old cathedral was modified by Inigo Jones.

Above the image of the old cathedral, there are some inscriptions recoding plagues that occurred during the 14th century, including what is known as the Black Death.

Apart from the drawing and the inscriptions described above, the church contains a few other inscriptions, which have been partially deciphered.

For the information of those visiting the church, it is near to Day’s bakery, where delicious snacks can be purchased. The village also contains a small museum, part of which is housed in a half-timbered building. However, for me, the highlight of the village is the drawing of old St Paul’s Cathedral in the church.

August 17, 2024

A visitor from Persia in a house in Sussex

PETWORTH HOUSE IN West Sussex is a huge palace maintained by the National Trust. It contains an unbelievably remarkable collection of old master paintings, including many by Joshua Reynolds, JMW Turner, and Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641). The paintings and many sculptures were collected by the 3rd Earl of Egremont, George O’Brien Wyndham (1751–1837), who was a patron of JMW Turner and John Constable, both of whom were regular visitors at Petworth House. When we visited the house in August (2024), we saw the paintings by Turner, but did not notice any by Constable. A full list of the paintings in Petworth is listed at: www.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:WikiProject_sum_of_all_paintings/Collection/Petworth_House .

While viewing the overwhelmingly splendid artworks at Petworth, a pair of paintings by Van Dyck intrigued me. Painted in 1622, one depicts Sir Robert Shirley (1581-1628), and the other his wife Lady Theresia Shirley (1589-1668). They are fine portraits, but what interested me was the lives of these two people.

The Safavid dynasty ruled Persia from 1501 until 1736. In 1598, Robert Shirley travelled to Safavid Persia with his brother Anthony to train the Shah’s army in the military techniques used by the English army. It is not clear who put the idea of visiting Persia into the minds of the Shirleys. One suggestion is that it was mooted by the Venetians. The modernisation of the military supervised by the Shirley brothers improved the fighting ability of the Persian army to such an extent that they were able to score a great victory in a war between the Safavids and their Ottoman neighbours in 1612. After Anthony left Persia (in about 1600), Robert stayed behind with 14 other Englishmen. In 1607, he married Sampsonia, whose portrait by Van Dyck hangs in Petworth. She was a Christian lady born into the Circassian nobility of Safavid Persia. After being baptised, she added the name Teresia to her own name, and became known as Lady Teresia Sampsonia Shirley.

The Safavid Shah Abbas (ruled 1587-1629) sent Robert to England in 1608 to encourage King James I to join a confederacy against the Ottoman Empire. While in Europe, Robert visited other rulers for the same reason. Between 1609 and 1613, he lived in Spain. His wife travelled from Persia to join him there. Between 1613 and 1615, Robert was back in Persia. Then, he returned to Europe, and resided in Spain.

It was in Rome in 1622 that Van Dyck painted the portraits of Sir Robert and Lady Teresia now hanging in Petworth. They were dressed in lavish Persian clothes. It has been suggested that these ‘exotic’ outfits attracted Van Dyck, but by 1622 this couple were already sufficiently celebrated to be worthy of the artist’s attention regardless of how they were attired.

Shirley’s final visit to Persia was in 1627, when he accompanied Sir Dodmore Cotton – England’s first ambassador to Persia. However, soon after arriving there, he died in Qazvin (now in northwest Iran). His wife took his remains to Rome in 1658. She retired to a convent in that city, and lived there until her death.

I have discussed only two of the multitude of paintings at Petworth. Most of the others we saw there were not only by great masters, but also worthy of study. Although the design of the rooms in Petworth is not as spectacular as in many other stately homes, the collection within it deserves a leisurely visit. And as there is so much to see in the way of artworks, the visitor should plan to spend several hours there. We were there for three hours and that was hardly long enough.

August 16, 2024

He who lacks imagination

My father, who died at the age of 101 in 2020, often used to say of people who lacked imagination:

“Like a tram he moves in pre-destined grooves”

I do not know whether he invented this short sentence or he had read or heard it somewhere else.

August 15, 2024

The artist Marc Chagall and a church in rural Kent

A TRAGEDY OCCURRED on the 19th of September 1963. Aged 21, Sara Venetia d’Avigdor Goldsmid lost her life in a sailing accident. She was the daughter of Major Sir Henry Joseph d’Avigdor-Goldsmid, (1909-1976) of the Jewish faith and his wife Lady Rosemary d’Avigdor Goldsmid, an Anglican. The family lived at Somerhill, a Jacobean mansion (now a school) near to the church of All Saints at Tudely (just under 2 miles east of Tonbridge). Lady Goldsmid and her daughter Sara used to worship in this small church, which dates to mediaeval times, if not before. Much of the existing structure was constructed in the 13th and 14th centuries, but it was heavily restored in the 18th century.

After Sara’s death, her parents wanted to do something to perpetuate her memory. They and others decided to restore the church. Part of this operation was to replace the existing plain glass east window with a commemorative window, which they asked the artist Marc Chagall (1887-1985) to design for them. This Jewish artist was chosen because Sara and her mother had admired Chagall’s stained-glass at an exhibition they had visited at the Louvre in Paris (France). These included some of the windows that Chagall had created for the synagogue of the Hadassah Medical Centre in Jerusalem (Israel). They were installed in 1962 after having been exhibited not only in Paris but also in New York City.

Chagall created the drawings for the windows, and they were translated into stained-glass by Charles Marq (1923-2006) of Rheims (France). When Chagall visited Tudely, and saw his window after it was installed and dedicated in December 1967, he was so satisfied with it that he offered to create stained-glass images for all the other windows in the church. His offer was accepted. He managed to complete this work, but it was some years before the congregation at Tudely finally agreed to replace the existing Victorian stained-glass windows in the church with those created by Chagall. It was only some time after the church warden, Kenneth Stinton, had seen the Chagall windows on display at the Royal Academy of Arts in Piccadilly in 1985 that the idea of replacing the Victorian windows with Chagall’s became acceptable. They were placed in the church by December 1985.

Many of Chagall’s windows at Tudely are rich in dark blue colouring. Entering the church and finding it suffused with predominantly blue light is like entering an underwater space. This might be intentional as poor Sara d’Avigdor Goldsmid’s life ended beneath the water of the coast near Rye (Sussex). If she saw anything at all as she sunk beneath the sea, it might well have been such a dark blue light. I have visited Tudely’s church several times, and each time the same thought occurs to me. My first visit must have been in the 1980s after December 1985, because I have never seen the church without all the Chagall windows installed.

The church is in a rural setting, surrounded by fields. It has become a tourist attraction, and is occasionally used to hold chamber music concerts, one of which I attended in the early 1990s when I was still practising dentistry in north Kent. Although a little remote, this gem of a church is well worth making an effort to visit it.

August 14, 2024

Workers in London’s Hampstead and the historian Thomas Carlyle

I AM NOT A GREAT fan of the style of painting found in pictures by the Pre-Raphaelite artists. Although not a member of that artistic circle, Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) created paintings in the Pre-Raphaelite style.

The Manchester Art Gallery contains a large collection of Pre-Raphaelite style paintings. Amongst these, one caught my attention. Entitled “Work”, it was painted between 1852 and 1865 by Ford Madox Brown. What interested me is that it depicts a scene in north London’s district of Hampstead.

Detail from “Work”

Detail from “Work”“Work” depicts two labourers (‘navvies) digging a hole in the street as part of the preparations for laying sewers. In the background, there are houses that strongly resemble buildings that can be seen in Hampstead today. The painting was inspired by a book which Brown had read: “Past and Present” by the historian Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) and published in 1843. The author discussed the nobility of labour in this book. Ford Madox Brown included a portrait of Carlyle on the right side of his painting. The canvas “Work” illustrates the contrast of the hard working labourers with the relatively wealthy, inactive bystanders.

An early study for Brown’s “Work” is his painting of Heath Street in Hampstead, which he created between 1852 and 1856 (https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/heath-street-hampstead-study-for-work-205501). The part of Hampstead depicted in “Work” is The Mount, which branches off Heath Street at an extremely acute angle. Brown had made a detailed study of the area in 1852.

Ford Madox Brown lived in many different places, including Manchester. However, I am not sure whether Hampstead was one of them until the end of his life. He did have a studio in Hampstead.He died in Primrose Hill (in his home at 1 St Edmunds Terrace), which is very close to Hampstead.

Lovers of Pre-Raphaelite artworks should not miss a visit to the Manchester Art Gallery. It should also appeal to those interested in modern architecture because the space between two parts of the institution has been roofed over and contains a interesting new staircase and a glass-floored bridge.

Depictions of Hampstead in painting always interest me because I was brought up in that neighbourhood and have researched it in detail whist preparing my book “BENEATH A WIDE SKY: HAMPSTEAD AND ITS ENVIRONS”. My title refers to the artist John Constable and his fascination with the cloudscapes that he could see from Hampstead, where he lived for many years .

August 13, 2024

He painted artworks on the floor using a household broom

ED CLARK (1926-2019) WAS born in New Orleans. He was an Afro-American. In 1944, at the age of 17 he joined the US Army Airforces. After the war, he received US Government financial assistance for further education, help given to those who had served in the military during WW2 (the GI Bill). He studied art in Chicago before moving to Paris (France). He arrived there as a competent figurative painter, but soon became fascinated with abstraction, such as practised by Picasso, Matisse, and Braque.

Although he was a competent portraitist, Clark began to question the value of realistic figurative painting when photography could do the job so well. He moved to creating works that were mainly abstract. Many of his paintings are on display at the Turner Contemporary Gallery in Margate until the 1st of September 2024.

Ed Clark with a broom

Ed Clark with a broomThe paintings that we viewed at Margate are exciting and most of them are almost, if not completely, abstract. For most of his creative life, Clark worked in an interesting way. First of all, he painted with his canvases spread out on the floor. This way, he explained in a film being shown at the exhibition, his paint was not subjected to gravitational pull. Most artists paint on surfaces which are far from horizontal – on easels, for example. This means that the wet paint is subject to gravitational pull before it has dried. By painting on the floor, Clark explained, this small but significant gravitational drag does not occur.

Another distinctive feature of the way Clark worked was his choice of brushes for applying the paint. He did not use artists’ paint brushes. Instead, he threw batches of paint onto his horizontal canvases and worked them into his pictures using ordinary domestic brooms, such as are normally used to sweep the floor. This is illustrated in the film, and the effects he produced using sweeping movements are beautiful and ingenious. In addition to brooms, he also applied paint with his hands, rubbing the paint into the canvas. Clark described that by working on the floor he became more intimately involved with his creations.

We had come to the Turner Contemporary to view some sculptures by Lynda Benglis, and had never heard of Ed Clark. However, after seeing the superb exhibition of his creations, we have become his fans.

August 12, 2024

The Mahatma standing by the cathedral in Manchester

THERE ARE MANY statues depicting Mohandas K Gandhi (the Mahatma; 1869-1948) all over the world. There is one in Manchester close to the city’s cathedral. A small notice next to it notes that it was gifted by the Kamani family to honour their grandfather Bhanji Khanji Kamani (1888-1979). Inaugurated in 2019, it is a project by the Shrimad Rajchandra Mission in Dharampur (Gujarat).

Shrimad Rajchandra (1861-1901) was a Jain philosopher, scholar, and reformer. Gandhi was introduced to him in Bombay in 1891, and the two men wrote to each other when the Mahatma was a lawyer and activist in in South Africa. Gandhi wrote in his autobiography that Shrimad was his “guide and helper” and his “refuge in moments of spiritual crisis”. Well, I did not know that.

As for Bhanji Khanji Kamani, the notice next to the statue in Manchester notes that he was “… a Fellow Scholar of Gandhi.” I am unclear about the meaning of this because Bhanji was about 19 years younger than the Mahatma. I wonder whether he was actually a disciple of Gandhi, rather than a Fellow scholar.

We saw the statue representing a man who advocated peaceful protest on a day when violent protests were predicted all over England.

August 11, 2024

A sculptor who uses both her digits and digital technology

THERE IS AN EXHIBITION of sculptures by Lynda Benglis (born 1941) at the Turner Gallery in Margate (Kent). They are produced using a combination of traditional modelling and modern technology.

First, she makes small versions of these in clay. Then she scans them digitally. Using computer software, she magnifies the 3D (three-dimensional) scan. Next, she uses a 3D printer to create exact but greatly enlarged plastic replicas of the original clay models. These are then used to create the final metal casts – the sculptures seen at the exhibition.