Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 33

November 16, 2024

Bringing a forgotten artist out of the shadows

THE BEN URI Gallery and Museum began its life in 1915 as a place where Jewish immigrant craftsmen and artists could exhibit their works. At that time, mainstream British artistic institutions were reluctant to include artists from recently arrived minority immigrant communities. Things have moved on a long way since then, and the organisation no longer confines itself to Jewish artists. Ben Uri’s remit:

“… has expanded to include relevant works by immigrant artists to the UK from all national, ethnic and religious origins, who have helped to enrich our cultural landscape.” (https://benuricollection.org.uk/)

My mother, the painter and sculptor Helen Yamey, was born in South Africa, and came to England in 1948. She was an immigrant artist.

When I was researching her life to write her biography, I discovered something about her which I had not known before. It was that during the first half of the 1960s, her sculptural work was chosen to be exhibited in several prestigious exhibitions. She exhibited alongside now famous artists such as Elisabeth Frink, Anthony Caro, David Annesley, Eduardo Paolozzi, Menashe Kadishman, William Tucker, Phillip King, David Hockney, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Paula Rego, Bridget Riley, Duncan Grant, and Jean Arp. As a youngster in the early 1960s, I was unaware that my mother’s work was rated as highly as those with whom she exhibited. It was only when writing her biography to accompany some photographs of her work, which had recently come into my possession, that I realised that although she was now forgotten by the art world, she had achieved something quite significant in the artistic world of the early 1960s. Having learned this about her artistic prowess, I discussed the matter with my daughter, who is a curator and a historian of art. In turn, she mentioned it to the current director of the Grosvenor Gallery in Mayfair. He suggested that I should contact the Ben Uri to find out whether they had any information about my mother.

The Ben Uri had no material about my mother, and were interested when I sent them information about her association with the Sculpture Department of St Martins School of Art and the exhibitions in which her work was shown. They decided to add her to their already extensive database listing immigrant artists from of 100 countries. After donating a copy of my book to the Ben Uri’s research library and having been interviewed by one of the organisation’s researchers, they added my mother, a long-forgotten sculptor, to their database. In addition, the researcher, Ms Milcic, has added an 800-word profile of my mother and her art to one of their websites. It can be read online here: https://www.buru.org.uk/contributor/helen-yamey- . This webpage also gives links to a site where some pictures of my mother’s sculptures can be viewed.

It gives me great satisfaction that my mother’s works, which had become largely forgotten, have at last been given some of the prominence they deserve. The reasons why she became forgotten and many other details about her life can be found in my recently published book “Remembering Helen: My Mother the Artist” (available from Amazon: www.amazon.co.uk/REMEMBERING-HELEN-MY-MOTHER-ARTIST/dp/B0DKCZ7J7X/)

Pleasing pictures in a gallery next to London’s Fitzroy Square

AT FIRST SIGHT, there seems to be little content in the 17 paintings on show at the Tristan Hoare Gallery in London’s Fitzroy Square until the 13th of December 2024. It is not long before you realise that these images that contain larges expanses of colour are quite pleasing and visually intriguing. The artworks, all of which were created in 2024, are by Vipeksha Gupta (born 1989) who lives and works in New Delhi (India). As I looked at her work, I was reminded of the paintings by Mark Rothko in which the viewer is confronted with large areas of colour. In Rothko’s case, the borders between one colour area and its neighbour are deliberately ‘fuzzy’, whereas Vipeksha Gupta defines these transitions more sharply, yet not completely abruptly.

The gallery’s website (https://tristanhoaregallery.co.uk/exhibitions/71-ebullience-vipeksha-gupta/overview/) explained:

“The subtle abstraction of her work is seen within the repeated marks, geometries and the resistant voids made within the material. The surfaces of these works are generated through the iteration of small units into patterns that the artist then proceeded to render dynamic through gestures of rupture, incision, or slippage. She created folds, hinges or selvages of light, around which darkness could pivot and ripple. Gupta carefully plays with the structure of the paper, creating an interplay between illumination and shadow. This use of light shifts the narrative of her work as these folds generate movement, granting fluidity to the deep and mesmerising colours which she carefully crafts.” Abstraction is art often a creator’s way of distilling the essence of something that could also be represented more obviously as a recognisable physical object or scene. In Gupta’s case, she seems to be experimenting with her media (Fabriano paper [handmade with cotton fibre], paint pigments, graphite, and charcoal) to create subtly interesting visual effects for the eyes of the paintings’ viewers to enjoy. In this, she is successful. What at first viewing appeared to be organised areas of colour can be seen to be more complex and interesting the longer one looks at them. In addition, these paintings are somewhat soothing to look at.

November 15, 2024

Haiku for a heron

November 14, 2024

I wondered if it was worth reading books by Charles Dickens?

WHENEVER CLASSIC BOOKS were recommended to me during my childhood, I never bothered to read them because I hated to be told what to read by people who had no idea what interested me. Therefore, until a couple of months ago I had not read anything by highly acclaimed British authors such as the Brontes, Thomas Hardy, Jane Austen, Scott, Trollope, Thackeray, and Dickens. I have read and enjoyed English translations of French authors including Balzac, Flaubert, and de Maupassant.

This summer (2024), we paid a visit to the delightful coastal town of Broadstairs in Kent. This place is rich in souvenirs of the author Charles Dickens (1812-1870). It was in this town that he worked on several of his novels. After our brief visit to Broadstairs, I was suddenly filled with the desire to begin reading something by Dickens to see what I have been missing for so many years, and to discover whether I ought to have followed the many recommendations I was given (during my youth) to read his work. I began with “Nicholas Nickleby” because some of it had been written in Broadstairs. After reading and enjoying this 600-page novel, I moved on to “Martin Chuzzlewit” (762 pages), which I have just finished. That I have already begun reading “Oliver Twist”, another novel by Dickens, shows that I have begun to like Dickens’s writing.

I do not find that reading Dickens is easy-going. Often, he says what could be said in a few words in many sentences, thus spinning out the story. Another problem is keeping track of the vast numbers of characters in the stories. It felt to me that every few pages, a new character is introduced. Some of them appear for a few pages and then disappear for a long time, only to reappear much later. So, when they do reappear, it is sometimes difficult to remember anything about them. As for the plots, they are complex, but fascinating. Despite the lack of conciseness, the huge number of characters, and the length of the novels, Dickens knew how to keep the reader engaged from start to finish. He had to do this because at first his stories were published as monthly episodes in magazines. If he had not kept his readers engaged one month, then they might not have bought the next episode a month later. Even though the plot acquires more and more sometimes seemingly unconnected strands, I felt instinctively that eventually they would coalesce. How Dickens kept track of what he was writing and did not ‘lose the plot’ amazes me. And how well he holds the reader’s attention is also a marvel.

Dickens’s mastery of detail amazes me. It is fascinating to read how parts of London, which I know well, were when Dickens was writing about them. His minute descriptions of aspects of daily life in early Victorian England are of great interest. His ability to portray villainous people is something else I have enjoyed. The villains and crooks are, for me, the most enjoyable of the characters in the two novels I have already read. Page after page, I realised that in the end they would receive their comeuppance, but how this happens eventually is a wonderful surprise that is revealed in the final pages of the books. Would I recommend reading Dickens? Well, I have been enjoying what I have read so far. To those who read quickly, I would strongly suggest trying Dickens. But for those who read slowly, I am not so sure. My reading habits have changed over the years. Had I attempted Dickens when I was younger, I doubt I would have read an entire novel. Now, in my retirement, I find that I am reading faster. Although Dickens should not be read too fast because of the incredibly large amount of detail he includes, I find that I can now cope with his writing and enjoy it. I am glad that I ignored the many who tried to persuade me to read Dickens when I was a child. I am pleased that at long last I have discovered how much fun it is to read his novels. I shall certainly be carrying something by Dickens to read during my next long-haul aeroplane journey.

November 13, 2024

Advertising in India a few months after the country became independent

IN AUGUST 1947, India and Pakistan became independent sovereign nations. Following this, vast numbers of Sikhs and Hindus fled from Pakistan to India, and many Muslims fled in the opposite direction. This mass migration of people was accompanied by unbelievably horrific incidents of violence; many lost their lives on both sides of the frontier. Meanwhile, in much of India, daily life for many went on without incident. A yearly publication was published in Bombay from 1919 until 1979. It was called “Times of India Annual”, but between 1942 and 1948, it was called “Indian Annual”. The 1948 issue of “Indian Annual” was published by the Times of India soon after Independence was achieved in 1947. I have a copy of this beautifully illustrated issue. In common with many magazines, it is amply supplied with advertisements. Studying these was interesting because although some of them seem to have recognised that India was independent of both the British Empire and separate from Pakistan, others have not taken this into account.

I imagine that many of the readers of the 1948 Indian Annual were Indians. The magazine includes advertisements for many products used by Indians. Many of these commercials depict faces or people. Some of them show people with faces that look Indian. These include the adverts for Firestone tyres, the India Tea Marketing Expansion Board, Cyclax (beauty products), Tata Steel, Saba Radio Company, and Himanlal Manchand (jewellers). Others feature people with faces that are unmistakably (white) European, for example: Ovaltine, Terra Trading Corporation (modern Czechoslovak glassware), Argoflex (cameras), Rogers (soft drinks), Yardley (beauty products), Rendells products (feminine hygiene), and Virol (a health product). Either these companies that used European faces were recycling pre-existing company advertising material or not sensitive to the fact that India was then independent, or both. Another possibility is that these companies were appealing to the spending abilities of the many European people who were to continue living in India until well into the 1970s. For even after Independence, there were institutions (e.g., some clubs and schools) in India that for many years were only for Europeans, but excluded Indians.

Several of the advertisements in the 1948 publication listed the cities where they had branches. Some of these listings ignored the fact that India and Pakistan were no longer parts of one country. Ovaltine was distributed by a company that had branches in Bombay, Calcutta, Karachi (Pakistan), and Madras. The mechanical and construction engineers Garlic &Co had branches in Indian cities and also in Lahore. And Modern Trading Company listed offices in Bombay, New Delhi, Karachi (Pakistan), Calcutta, and Lahore (Pakistan). Another advertisement, that for the Chicago Telephone & Radio Co. Ltd, includes listings of offices both in India and Pakistan. The Rootes Group, which manufactured cars like the Humber, the Hillman, and the Sunbeam Talbot, list their (I quote) “Distributors in India” as being in towns such as Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Rawalpindi. Had the advertiser not realised that these towns were now no longer in India, but in Pakistan? In all the cases I have mentioned in this paragraph, the advertising agencies seemed to have ignored the fact that what had once been (greater) India was now India and Pakistan. Given what was happening in the way of the misery caused by the partition of India at the time the Annual was published, it seems odd or even insensitive that the advertisements display no sign that the Subcontinent had been divided.

After Independence, Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to move India into what he perceived as the ‘modern era’. Some of the advertisements reflect this both in their design and the products they were promoting. The advert for Godrej shows some tubular household furniture of a design that many would have considered avant-garde in 1948. An advertisement for Indian-made Panama cigarettes is reminiscent of the Italian Futurist style. Likewise, for the Tata steel advertisement. This has futurist features but also veers towards the Soviet Socialist Realism style.

Finally, we come to a very interesting advert, that for the Bombay based Himanlal Manchand jewellers. It depicts Indian warriors on horses and is covered with crests of various rulers of Princely States and that of the Governor of Bombay, which is accompanied by the words:

“By appointment to H.E. Rt. Hon’ble Sir John Colville, Governor of Bombay”

Sir John Colville (1894-1954) was appointed Governor of Bombay in March 1943. He held this post even after India became independent, and was replaced by Raja Maharaj Singh in early January 1948. The jewellers were also by appointment to the princely rulers of Baroda, Jodhpur, Cooch-Behar, Jubbal, Jaipur, Indore, Palanpur, and Dewas. These maharajahs had been the rulers of ‘semi-autonomous’ (vassal) states within the British Empire. All of those listed became incorporated into the India which came into existence in August 1947. Their rulers were recognised officially by the Indian government until 1971. Between 1947 and 1971, these and other rulers of princely states received a privy purse from the Indian government. In 1971, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi put an end to the majority of these payments and de-recognised their titles and put an end to all of their royal privileges. So, in 1948 when Himanlal Manchand placed their full page coloured advertisement in 1948, they were entitled to show off their appointments to Indian royalty. The advertisements alone make the 1948 Indian Annual an interesting curiosity. The articles in the magazine along with many of its fine illustrations make it into a real treasure of great historical interest. While writing this piece, I discovered that the 1949 issue can be read online (https://archive.org/details/dli.venugopal.824/page/n91/mode/2up) . Skimming through this, I noticed that some companies still depicted European faces in their adverts and others included cities in Pakistan in the lists of their branches. This was despite the fact that since October 1947 Pakistan had been fighting a war over Kashmir. This only ended on the 1st of January 1949.

November 12, 2024

Residences close to the railway tracks in north London

LIVING NEAR BUSY railway lines can be a noisy experience. The American-born architect Neave Brown (1929-2018), who worked for the London Borough of Camden, understood this when he designed a housing estate that is situated beside a curve of the railway between Kilburn High Road and South Hampstead stations. Six parallel tracks carry trains regulatly past this site. So, living alongside these tracks could be far from peaceful.

Side of the block facing the railway tracks

Side of the block facing the railway tracksNeave Brown designed a public housing estate next to this curve. Called the Alexandra and Ainsworth estate, it was designed in the Brutalist style of architecture, but in such a way that the buildings themselves muffle the sounds coming from the railway tracks. How he did this is well explained in a Wikipedia article:

“The higher, eight-story block directly adjacent to the railway line is organised in the form of a ziggurat, and acts as a noise barrier that blocks the noise of the trains from reaching the interior portion of the site, and its foundations rest on rubber pads that eliminate vibration.”

This step-like construction is both impressive and sculptural. Far from being inhuman as many Brutalist constructions can be, the estate, which is rich in vegetation, looks like a pleasant place to live. This contrasts with the pairs of tower blocks that stand on the other side of the tracks. As one of its residents, the architect Lefkos Kyriacou wrote (http://alexandraandainsworth.org/history/):

“… Alexandra Road still retains its cinematic wonder but having suffered the problems that have blighted much of Britain’s post-war social housing it is emerging from the shadows, not only as a valuable part of our national heritage but as a viable example of how mass housing can succeed.”

What is more, and this is a measure of its success, I have read that Neave Brown’s estate has suffered far less from vandalism than almost all of Camden’s other residential estates.

November 11, 2024

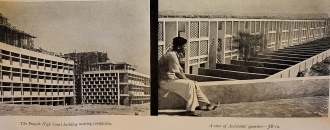

Photographs of Chandigarh in an old Indian magazine

DURING MY TEENAGE years, I had the idea that later I might train to become an architect. I enjoyed drawing, and read books about twentieth century architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier. When the Bauhaus exhibition was held at the Royal Academy in London (September to October 1968), I visited it three times. My enthusiasm for becoming an architect ended after lunch one day when walking from the Highgate School dining hall back to the classrooms. Suddenly, I thought that instead of designing great buildings such as those created by the architects, whom I had read about, I might end up designing extensions and garages for people’s houses. This fleeting thought made me give up the idea of becoming an architect. However, since then, I have continued to enjoy looking at, and reading about, architecture.

One of the 20th century architects who intrigues me much is Le Corbusier. I have seen many of his creations in France and a few in the Indian city of Ahmedabad. But I have never been to Chandigarh in the Punjab. It was to be the new capital of the Indian Punjab. The old capital, Lahore, found itself in Pakistan after 1947. This was a new city that Le Corbusier helped to design in the 1950s – both the layout and many of its buildings. Last year, I acquired a copy of a magazine called “Times of India Annual”. I have the 1955 edition. Although much of Chandigarh was already built by 1955, it was far from completed. The magazine contains an illustrated article by the British Modernist architect Edwin Maxwell Fry (1899-1987).

The article is illustrated with photographs that show both the novel designs employed for residences as well as some of the larger buildings including the Punjab Engineering College, the High Court, and a school. Several of Le Corbusier’s major projects such as the Palace of Assembly and his Open Hand Monument are not illustrated because they had not been completed by 1955. The Secretariat Building designed by Le Corbusier was complete when the article was published, but has not been included amongst its illustrations. The pictures tend to concentrate on the designs for dwellings that were economical without seeming mechanical or inhuman.

Having a great interest in Le Corbusier and Chandigarh, I was excited to find an article written by Fry, one of the city’s planners, at a time when the place was still in its infancy. For three years, he and his wife Jane Drew (1911-1996) worked with Le Corbusier on the planning of Chandigarh. Knowing that, I thought it would be interesting to see what Fry wrote in the magazine. Sadly, Fry’s article’s content is rather anodyne and self-congratulatory. Nevertheless, I am pleased that I have the magazine because apart from Fry’s article, it contains a wealth of other material – both written and illustrative.

November 10, 2024

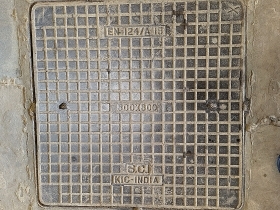

From West Bengal (India) to a floor in north London

KENWOOD IN NORTH London (next to Hampstead Heath) is a delightful place to visit at all times of the year. Amongst its attractions are a collection of fine paintings within Kenwood House; architectural features designed by Robert Adam; beautiful grounds with a lake; some modern sculptures; and a refreshment complex housed in the former servants’ quarters and stables. Close to the cafeteria, there are some toilets for use by visitors.

After visiting the ‘gents’ toilet, I looked down at the floor of the passageway leading to it, and saw a square, metal manhole cover. It had some lettering on it. Amongst the lettering, I noticed the following “KIC-INDIA”. Seeing this made me wonder if this manhole cover in north London had been made in India.

When I returned home, I looked at the Internet to see whether I could find out anything about the connection of this manhole cover with India. KIC-INDIA refers to an ironworks in India called KIC Metaliks Ltd (www.kicmetaliks.com), whose office is in Calcutta (Kolkata) in West Bengal. The company website revealed:

“K I C Metaliks Limited, founded in 1986 and headed by entrepreneur Radhey Shyam Jalan, is a leading pig iron manufacturer in West Bengal headquartered in Kolkata. Publicly listed on the BSE, the company has over 35 years of experience catering to hundreds of satisfied customers using cutting-edge technology. Its factory in Durgapur produces pig iron with a current capacity of 2,35,000 MTPA. The company takes a prudent yet ambitious approach to capacity expansion to become a dependable pig iron supplier.”

The company was formerly known as ‘Kajaria Iron Casting Limited’, and its plant is at Durgapur, 100 miles northwest of Calcutta. While searching the Internet, I came across other examples of KIC manhole covers in the British Isles, including at Bangor (County Down), South Shields (Tyne and Wear), and Plymouth (Devon).

Often when I am out walking, I look down at manhole covers. Sometimes they have interesting designs on them. When I spotted the KIC manhole cover at Kenwood today (6th of November 2024), it was the first time I had seen one made in India set into a floor in England.

November 9, 2024

Watch where you step!

A man walking in Bangalore

Fell through a hole in the floor

As he dropped down

He began to frown

Then the poor fellow was seen no more

November 8, 2024

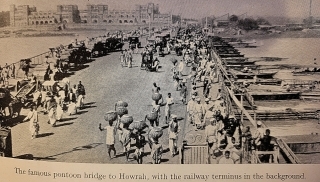

A bridge across the river in Calcutta

I HAVE BEEN to Calcutta (Kolkata) several times, and each visit I am impressed by the Howrah Bridge. It is a suspension type balanced cantilever bridge that carries pedestrians and road traffic across the Hooghly River, which is part of the mighty Ganges. This massive bridge contains 26,500 tons of steel riveted together – it contains no nuts and bolts. When it was opened for use in 1943, it was the world’s third largest cantilever bridge.

Before the present bridge was constructed, there was another bridge that crossed the Hooghly. Unlike the existing bridge, its roadway was close to the water. It was a pontoon bridge. Its roadway rested on floating pontoons. It had a section that could be opened to allow the passage of large vessels travelling along the Hooghly. The pontoon bridge was completed and ready for use in 1874. It served its purpose until the current bridge was opened in 1943.

The pontoon bridge

Recently, I obtained a book called “Wonderful India”. Inside its front cover, a former owner of the book had handwritten “LW Morris, Royal Air Force, Calcutta-July 1943”. The current bridge was opened in February 1943. The book does not contain a picture of that bridge, Instead, it contains a photograph of its predecessor, the pontoon bridge, with the caption:

“The famous pontoon bridge to Howrah, with the railway terminus in the background.”

I am guessing that had the new bridge been near completion when this book was compiled, it would have included this wonder of bridge engineering. As the book has no date of publication, the inclusion of the pontoon bridge rather than the suspension type cantilevered bridge, I feel that the book must have been compiled long before the new bridge was near completion, That the book includes a photograph of another bridge across the Hooghly: The Willingdon Bridge (also known as ‘Vivekananda Setu’). As this bridge (upstream from the Howrah Bridge) was completed in 1931, it would seem that “Wonderful India” was published sometime between 1931 and early 1943.

Crossing the Howrah Bridge as a pedestrian is a thrilling experience. One shares the footway with many other people. A large proportion of them are carrying loads on their heads, The water is far below one side of the footway, and the wide roadway is on the other. From the footway, one can see a huge flower market and several bathing ghats lining the riverbank. A steady stream of traffic flows across the bridge, including buses painted in many colours; ancient, yellow-painted Ambassador taxi cabs; hand-hauled carts; trucks; and other motor vehicles. And all of this crosses a stretch of the holy Ganges River. Although traversing the present Howrah Bridge is a memorably enjoyable event, which I am happy to repeat whenever I visit the city, crossing the former pontoon bridge must have been at least as exciting.