Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 34

November 7, 2024

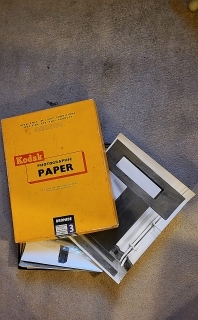

Finding a box of photographs and rediscovering a forgotten artist

UNTIL ABOUT 1991, my widowed father resided in my childhood home in northwest London. For as long as I can remember, there was a collection of black and white photographs in a cardboard Kodak photographic paper box. The photographs contained images of sculptures, which my mother Helen Yamey (1920-1980) had created at St Martins School of Art in London during the later 1950s and first half of the following decade. In 1991, my father married again, and moved from our childhood home to another address. Every now and then, after my father moved, I used to ask him what had happened to the photographs. He used to reply that he did not know where they were. Maybe, he suggested, they were stored somewhere in the garage of his new home. He died in 2020. After that, I thought that it was extremely unlikely that I would ever set eyes on the photographs again.

A year or two after my father’s demise, his widow, my stepmother, arranged to meet me at a café. When she arrived, she was carrying a plastic carrier bag, which she handed to me. To my great delight, I found that it contained the Kodak box filled with photographs of my mother’s sculptures. I posted a few of these images on the Internet. Some months after that, my friend Edesio mentioned that he was impressed by the images of my mother’s sculptures, and suggested to me that I should write something about my mother and her art. This I have done.

When I began writing my mother’s biography, our daughter Mala, who is an art historian and a curator, sent me a pdf file containing the contents of a catalogue of an exhibition held at London’s Grosvenor Gallery in the 1960s. It contained mention of some of my mother’s work that appeared in the exhibition. Mala did a little more research and discovered the existence of catalogues of other exhibitions in which my mother’s sculpture was included. I investigated these catalogues and came across a few more, I was surprised by what I discovered.

During the first half of the 1960s, my mother’s sculptures were selected to appear in exhibitions alongside artworks created by artists, many of whom are now quite famous. These include, to mention but a few, David Hockney, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Howard Hodgkin, Bridget Riley, Kim Lim, and LS Lowry. These exhibitions were held when I was between 8 and 13 years old. In those days, I was not particularly interested in my mother’s artistic activities and was too young for the names of these artists to mean anything to me. In addition, I do not recall even having been told that my mother was participating in exhibitions, let alone showing her work alongside that of these now famous creators. So, until I studied these catalogues more than 40 years after my mother died, I had no idea that for a while she was in the vanguard of 20th century British sculpture. Had I not been stimulated into beginning to write about her, I would not have known that my mother, who never boasted about her achievements, had been an artist of such a high calibre.

I have written my memories of my mother in a book called “Remembering Helen: My Mother the Artist” (available from Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0DKCZ7J7X/) . In it I have tried to describe her upbringing; what she was like as a mother; and her achievements in the world of sculpture. I have included many of the images I found in the box of photographs, and our daughter has written some insightful notes on her grandmother’s sculptural styles and the techniques. I hope that my book will help bring my mother’s artistic achievements out of obscurity. Modest as she was, I feel that it would be good if she were to get at least a little of the fame she deserved.

November 6, 2024

Two festivals

November 5, 2024

Off with his head in the centre of Norwich

THE CHURCH OF St Peter Mancroft stands above the marketplace in the centre of Norwich. Built between 1430 and 1455, it is an elegant example of the Perpendicular style. It was constructed to show off the wealth of the 15th century citizens of Norwich. It is filled with interesting features. I will discuss two of them.

The church contains a Resurrection tapestry, which is in fine condition. It was woven by Flemish weavers in 1573, and might have once been used as an Easter Day covering for the front of the high altar. The tapestry depicts the Easter story in three episodes. The central panel shows Christ emerging from his tomb. In another panel of the tapestry, Jesus is depicted as a gardener, which is how he appeared to Mary after he had left his tomb (John, chapter 20).

The tapestry is kept at the west end of the church close to the font. The other feature that I will describe is in the chancel in the eastern half of the church. It is a memorial to the polymath and writer Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), who was a parishioner of St Peter Mancroft. He was buried in the church and lay undisturbed until 1840, when workmen accidentally broke open his coffin. Then, his skull was removed from the rest of his skeleton for phrenologists to study it. It was only in 1922 when the detached skull was reburied in St Peter Mancroft, but not in the same place as the rest of Browne’s body. The burial register for 1922 recorded the skull as being aged 317 years,

Browne, who was interested in everything in a scholarly way, would most likely have approved of having his skull investigated by phrenologists.

Although visiting the Anglican cathedral is one of the highlights of a trip to Norwich, St Peter Mancroft should not be missed.

November 4, 2024

Souvenirs of imperialism at the British Museum

THE BRITISH MUSEUM contains many objects that were obtained when much of the world was part of the British Empire. Over the past couple of years, the artist Hew Locke (born 1959) has been selecting items in the museum’s collections and putting them together in a special exhibition called “What have we here?”. The exhibition will continue until the 9th of February 2025.

The items he has chosen are exhibited alongside sculptures and other artworks he has created in recent years. Each of the museum objects that Locke has chosen is accompanied by a short text that places the exhibit in the context of British imperialist exploits and exploitation. This has been done sensitively and gives the viewer an idea of what the objects meant to their original owners and why British collectors deemed them worthy of bringing home to England as ‘souvenirs’ of their activities in far off lands.

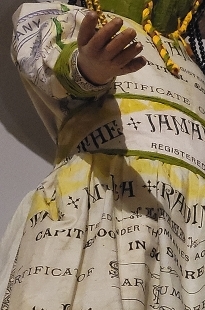

Interspersed amongst the exhibits chosen from the British Museum’s collection there are artworks by Hew Locke. Each of these beautiful things has been created to illustrate aspects of colonialism. For example, the model boats he has made symbolise exploration, trade, and the transport of goods and people (often against their will). There are also several historic companies share certificates on which Locke has added paintings. The shares were issued by companies that used slave labour. Perched above the display cabinets are a series of well-crafted but grotesque models of people, often dressed in clothes made from fragments of company documents. They represent the people who were downtrodden by their imperialist rulers.

In this exhibition, Locke neither seeks revenge nor condemns the activities of the colonialists. Instead, he tries to improve our understanding of what happened, hoping that history will not repeat itself. As with many other of Locke’s creations, this exhibition at the British Museum is both imaginative and eye-catching. It is well worth a visit.

November 3, 2024

Pasternak, Mandelstam, and Stalin: was the pen mightier than the sword?

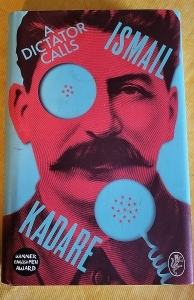

LIFE IN STALIN’S Russia was extremely precarious for writers. One small mistake could lead to imprisonment and/or assassination. This was also the case in Enver Hoxha’s Albania, as the country’s famous author Ismail Kadare (1936-2024) knew only too well.

In 1934, the author Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) is widely believed to have received an unexpected telephone call from no lesser person than Russia’s dictator Joseph Stalin. What Stalin said to Pasternak and how Pasternak replied is the subject of a novel, “A Dictator Calls”, published in 2022 and written by Ismail Kadare. The author convincingly demonstrates that nobody can recall what was said during this brief but significant telephone conversation that occurred in 1934. Kadare provides 13 versions of what might have happened during this three-minute telephone call. At one point, he questions whether the call ever happened, but I felt after reading the book that it was likely to have happened.

A common theme amongst the 13 recollections of this telephone call is that Stalin was calling to find out Pasternak’s views on the poet Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938). At the time of the call, Mandelstam, who had recently written a poem critical of Stalin, was in prison. It seems from what Kadare has written in his novel, which is based on facts (such as they are), that Stalin might have been hoping the Pasternak would say something that might help save his fellow author, the poet Mandelstam. In this fascinating novel, I felt that Kadare was questioning whether omnipotent dictators like Stalin and Hoxha feared, possibly secretly, the power of critics such as the poet Mandelstam, or in the case of Albania, Kadare. As with so many of Kadare’s novels, this relatively new one gives the reader some insight into the nature of secrecy, the contortion of truth, and uncertainty, which prevailed in regimes such as Stalin’s Russia and Hoxha’s Albania. Although difficult to understand in places, “A Dictator Calls” is a fascinating novel, which kept me intrigued all the way through it.

Kadare’s novel has been translated from Albanian into English by John Hodgson. I feel that a good translation should read in such a way that one cannot realise that it is a translation. It should read as if it were originally written in the language into which it was translated. Hodgson has achieved this very successfully.

November 2, 2024

From India’s Punjab to London’s Primrose Hill

WHEN THE PUNJAB WAS divided (by the British) between Pakistan and India in 1947, its former capital, Lahore, became a Pakistani city and the Indian part of the region was left without a capital. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, decided that instead of assigning an existing city to become the capital of India’s Punjab a new city should be created. It was to symbolise the birth of modern India. A team of architects led by the Swiss born Le Corbusier began designing the new city, Chandigarh, in the early 1950s. In late 1953, it became the capital of India’s Punjab, which was later further divided into Punjab and Haryana states.

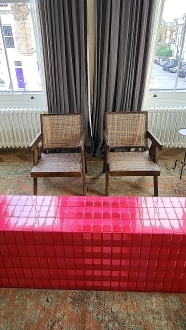

Amongst those who were on the team designing Chandigarh was Le Corbusier’s cousin, the architect Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967). He designed much of the furniture installed in the buildings created in Chandigarh. According to one source (www.worldofinteriors.com/story/pierre-jeanneret-and-le-corbusier-chandigarh-furniture):

“Pierre Jeanneret, was strongly influenced by local materials and craftsmanship, with a Modernist twist. Due to the vast scale of what needed to be created for an uninhabited city – from Palace of Assembly chairs to university cafeteria tables and and linen baskets – Jeanneret experimented with what was on hand. Iron Sikh Sarbloh bowls became lampshades; mango tree trunks became tables. Readily available materials such as bamboo, teak, rope and wicker were woven into the designs.”

Recently, I saw a couple of examples of this furniture on display at a special exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Today, the 29th of October 2024, we visited an exhibition, “Syncretic Voices:Art & Design in the South Asian Diaspora”, in a private house near London’s Primrose Hill. What made it special for me is that there were many examples of Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture on display. The exhibition ends on the 1st of November 2024.

The house near Primrose Hill is owned by Rajan Bijlani, whose parents came from India to the UK in 1975. Rajan has been collecting Jeanneret’s Indian furniture for some time, and he showed it to us. Of particular interest was a table with a zinc table-top, which was once used in the Punjab University cafeteria in Chandigarh. Many of the other pieces on display were chairs and stools. There was also a shelving unit designed to hold files. Most of the furniture came from various government buildings in Chandigarh. Some of the pieces still have their original inventory numbers painted on them.

The furniture is in several rooms of the house. The walls of these rooms are decorated with attractive modern artworks by several artists of Indian origin including Vipeksha Gupta, Rana Begum, Soumya Netrabile, Tanya Ling, Harminder Judge, and Lubna Chowdhary. Rajan told us that they were all for sale and he was holding them as consignments from various galleries. He is also selling some of his Jeanneret furniture. Rajan showed us around and was a perfect guide. It was a great pleasure and privilege to have been able to see his beautifully designed home and the fascinating furniture and other artworks displayed within it. If you wish to see this exhibition before it closes, visit: https://www.rajanbijlani.com/about

November 1, 2024

Wonderful India (as it was) in English, Bengali, and Urdu

IN A SECONDHAND BOOKSHOP in Thame (Oxfordshire) I purchased a book called “Wonderful India”. It must have been published by 1943 because inside its front cover there is the name of its first owner, LW Morris, and next to that he added “Royal Air Force, Calcutta, July 1943”. The book is trilingual. Its text is written in Bengali (Bangla), English, and Urdu. It was published by The Statesman and Times of India Book Department. The Statesman is a newspaper that was founded in 1818, and published simultaneously in Calcutta, New Delhi, Siliguri and Bhubaneswar. The Times of India was founded 20 years later. The gloriously illustrated book, which covers pre-Partition India, as well as Sri Lanka, Burma, and Nepal, contains no text in Hindi. In British India, the official languages were English and Standard Urdu, and later Standard Hindi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Languages_with_legal_status_in_India#History). Oddly, for many years Bengalis were opposed to using their language as an officially recognised one, for a long time preferring to use Persian for formal (especially commercial) use (https://thespace.ink/bengali-and-persian-in-british-raj/). Yet despite this, the book I found favours Bengali and omits Hindi. I suspect that because the book might well have been published in Bengal, the Bengali script has been included. Hindi written in the Devanagari script only became the official language of India in September 1949, several years after “Wonderful India” was published.

Dhaka (now in Bangladesh)

The book covers all the regions of pre-Independence India as well as some of its neighbours. It is rich in black and white photographs, many of which are superb examples of photographic technique. Each picture is captioned in Bengali, English, and Urdu. The only pieces of prose are the general introduction (which includes a photograph of Mahatma Gandhi) and introductory paragraphs at the beginning of each section. The Urdu introduction is at the rear of the book, and is next to a picture of Jawaharlal Nehru. There is no picture of any member of the British Indian hierarchy.

Bangalore, a place which I have visited often, is given only one sentence at the beginning of the section on Mysore and Coorg:

“The British retain some territory at Bangalore, which is the administrative headquarters of the state, while Mysore is the capital.”

There are three photographs of the city, Sadly, not the most interesting in the book. To compensate for this, the book is filled with pictures of touristic sights and daily life of India as it was before WW2 had ended. The book provides a fascinating window on a part of the world that has in many aspects changed beyond recognition.

October 31, 2024

A wall of art on London’s Portobello Road

MORLEY COLLEGE WAS founded in 1889 by Emma Cons (1838-1912), who was an artist, social reformer, and suffragette. The college was established to provide education to diverse groups of people living in London. It was named after the wool manufacturer and Liberal MP Samuel Morley (1809-1886), who endowed much money to Emma for the creation of her college. It is one of the oldest of Britain’s providers of education for adults. Its first branch was, and still is, in Lambeth. There are now other branches including one at Wornington Road in North Kensington.

In North Kensington, the stretch of Portobello Road between Golborne Road and Raddington Road is lined by a wall along most of its east side. Students from Morley College have created a series of pictures that are supposed to capture the vibrant atmosphere of Portobello Road and North Kensington, and do so successfully. These images have been attached at intervals along the wall. The collection has been given the name “Street Art Market -Portobello Wall (2024-2025)”. It is one of a series of annual public art commissions, the first of which appeared in 2009. The idea behind this ongoing project is to liven the rather dull stretch of Portobello Road that connects the two popular street markets, one on Portobello Road, and the other on Golborne Road. The result is usually very pleasing, and, surprisingly, does not attract the activities of graffiti ‘artists’, who often deface public surfaces with their spray paints.

October 30, 2024

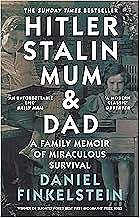

Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad

I have just finished “Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad” by Daniel Finkelstein.

Based on the true story of his parents and other family members, this is a page-turner. His mother’s family, German Jews, were caught up in Hitler’s genocidal activities. His father’s family were sucked into Stalin’s notorious Gulag system. Many members of the author’s family lost their lives during WW2. However, some of them survived. Finkelstein guides the reader effortlessly through the history of this horrific period of Europe’s history. Meticulously researched, this is an engaging read and very fascinating.

I can strongly recommend this book.

October 29, 2024

The Imaginary Institution of India at London’s Barbican Centre

THE OBJECTS IN an exhibition are usually chosen to fit in with a particular theme. An exhibition might be based on the work of an individual artist or a group of artists; on a style of art (e.g., Impressionism or Expressionism or portraiture); on a specific genre (e.g., etchings or sculpture or paintings or photographs); a period of history. It is the latter theme – a period of history – which has been adopted to create a superb exhibition, “The Imaginary Institution of India” at London’s Barbican gallery. This show is on until the 5th of January 2025.

The theme connecting the artworks on display at this exhibition is India during the period from 1975 to 1998. You might well wonder why these years have been singled out. Some landmarks during these years include Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s proclamation of a state of emergency in 1975; problems in West Bengal (in 1979); the founding of the BJP party; inter-communal problems; the attack on the Golden Temple in Amritsar (1984); the toxic leakage at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal; Hindu-Muslim tensions in Ayodhya; the destruction of the Babri Masjid (in Ayodhya); terrorist attacks in Bombay; and India’s successful underground nuclear tests. These events and many others occurred during the period covered by the exhibition.

The works on display at the exhibition are, according to the Barbican’s useful handout (a booklet), expressions of the various artists’ reaction to the events and social upheavals occurring in India during the years 1975 to 1998. The booklet describes what the exhibition’s organisers believe were the artists’ (political) messages being expressed in their creations. Interesting as these observations are, the works on display can be enjoyed without having any knowledge of what might have or might not have been going through the artists’ minds while they were producing their artworks. The exhibition provides a wonderful display of the excellence of Indian art produced during the period covered by the show.

I had not heard of most of the artists apart from MF Hussain, Bhupen Khakar, Sudhir Patwardhan, and Arpita Singh. The works that I liked most are by Patwardhan, Singh, Gieve Patel, and some lovely bronzes by Meera Mukherjee. I was also impressed by a set of collages by CK Rajan. That said, almost every work on display is worth seeing. The only disappointment for me was a video-based installation by Nalini Malani.

The Barbican has displayed these works in this exhibition both brilliantly and dramatically. I hope that the seemingly specialised nature of the theme of the exhibition (and its rather odd name) will not deter people from experiencing this superb collection of artworks.