Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 66

January 29, 2014

68 TTPs too many! Or, why lists like that won't help improve our junior officers

By Captain Jordan

Blashek, USMC

Best Defense guest

respondent

Captain

Jesse Sladek is the type of leader I would want as a commanding officer. ‘Just

giving a damn' goes a long way in leadership, and Captain Sladek clearly does. The

learning curve for a new infantry officer is steep, and there is no substitute

for a good company commander to mentor him through the first few months.

That

said, I don't find Sladek's "69 TTPs" particularly useful. They

range from insightful (#61: Often

commanders ... are not tracking the same reality as you), to obvious (#51: Lead

from the front), to uselessly vague (#57:

Be aggressive). The majority are lessons every infantry officer should have

taken away from the schoolhouse.

The

real problem though is that they were written as a list without explanations

for why

each one is important. To give the simplest example, #2 says to "wake up before

0500 five out of seven days a week." Why? What does that have to do with

leadership? The answer might be that a good leader should be the first to

arrive and the last to leave every day because it demonstrates dedication and

earns loyalty. Or perhaps, if your subordinates consistently see you arriving

after them, they will assume you were sleeping while they were working. But

waking up at 0500 just for the sake of getting up early is senseless.

Here's

a more serious example: TTP #65 says, "70% now is better than 100% an hour from

now." But is this always true? The reason it might be true is that in combat

there is a trade-off between time and certainty. When making decisions, platoon

leaders will never have the amount of certainty they want due to the fog of

war. There is risk in acting without enough information, but there is also risk

in waiting too long because the enemy is maneuvering too. Since the enemy

operates in the same environment of uncertainty, we can gain an advantage by

acting more quickly than him if we

have enough information. New platoon leaders should think about how they will know when 70 percent is

enough. This requires critical thought, a nuanced mind, and the ability to ask

the right questions to the right people both in training and in combat.

I

appreciate Captain Sladek's effort to pass on good information. I just would

prefer fewer TTPs with better explanations for why they are good practices. Just

like in a mission statement, the intent -- or the reason why -- is always the

most important part of any task. Lists are great for not forgetting things, but

they're less effective when it comes to learning valuable lessons or thinking

critically. In fact, the military already has far too many lists that feed the

uncritical bureaucratic mentality that Major Matthew Cavanaugh so eloquently

decries in his inaugural post on Warcouncil.org.

So

rather than trying to remember 69 different TTPs, I would suggest that 2nd lieutenants

focus on just one: "Think deeply about your job and figure out the why behind everything."

Everything else is secondary. The best infantry officers are those who

possess a certain mindset developed by thinking deeply about their job, their

leadership style, and the challenges they will face in combat. Adopting

hundreds of tried TTPs will help you as you develop, but it's the ability to

face the confusion of the modern battlefield that matters in the end. That

requires a nuanced mind capable of critical thought and the humility to ask the

right questions. Such character and maturity required for this can't be

assembled from a checklist of TTPs.

Captain Jordan Blashek is an infantry

officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. He served as a weapons platoon commander and

company executive officer in 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, deploying in 2011 to

Southeast Asia and the Horn of Africa on the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit. In

2013, he deployed to Helmand Province, Afghanistan, as an advisor to the Afghan

National Army's 215 Corps. He graduated from Princeton University in 2009 with

a bachelor's degree in international affairs.

Kafka and Orwell: The rest of this headline has been redacted by the NSA

By Ben FitzGerald

Best Defense office of

national security literary affairs

Kafka,

not just Orwell, helps us understand surveillance programs.

Edward

Snowden's revelations have drawn

frequent and understandable references to George Orwell's dystopian vision from

1984, with notable mentions

by Judge

Richard Leon

and Snowden

himself.

Orwell offers a powerful literary metaphor for understanding the perils of a

surveillance state. However another literary master, Franz Kafka, can help us

understand the deeper philosophical and governmental issues at hand today.

In

The Trial, Joseph K begins his

Kafkaesque nightmare in shock at his arrest for an unnamed crime he does not

know he has committed. Unlike Winston Smith, K. "...lived in a country with a

legal constitution, there was universal peace, all the laws were in force..."

making his subsequent treatment all the more horrifying. Judged by an unnamed

organization, K.'s world is turned against him, he is consistently denied

access to information about his case, and any insight he gains simply reveals

more secret bureaucratic machinations, further heightening his helplessness and

isolation.

Storing

and analyzing people's data without their knowledge "affects

the power relationships between people and the institutions of the modern state" in a Kafkaesque

manner, as Daniel

Solove

argues. But the problem goes beyond this argument. Taking a ‘big data' approach

to surveillance moves analysis from causation to correlation. ‘Collecting

everything'

to find potential threats therefore means that the data of the innocent is

being used to find the guilty, analyzing all parties without their awareness.

The

tools for this collection and analysis aren't intentionally overt as in a

totalitarian Orwellian state. Rather, backdoors and bulk collection

techniques subtly leverage the everyday technological tools of free and open

societies. This ‘dual use' subversion means that, like K., we don't just suffer

from the shock of surveillance (or arrest) but from losing trust in our

technology and government while also wondering what other actions are being

taken without our knowledge. As with K., the answers are unknowable. The

director of national intelligence does not provide accurate

testimony

on their surveillance programs and if Apple, RSA, Cisco and their peers were

in fact creating surveillance backdoors with the NSA, they would still be

forced to issue similar denials.

We

do not yet live in an Orwellian state so, in theory, we have legal recourse as

another means to ease our surveillance concerns. Unfortunately, legal process

has been perhaps the most Kafkaesque aspect of this whole affair with ongoing

challenges to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, prohibitions on

businesses reporting

on NSA data requests,

the Department of Justice providing wholly redacted

arguments,

and judges offering circular

arguments.

Considering

Orwell and the technical act of collection is vitally important but focusing

purely on this problem runs the risk of missing deeper issues or, worse,

pushing for reforms that weaken the NSA in areas where it operates legitimately

to protect our national security. Transparency and trust, or the lack thereof,

are at the heart of both Kafka's writing and our current surveillance issues.

Addressing the Kafkaesque aspects of the government wide bureaucracy, policies

and laws behind collection programs offers an opportunity to address these

fundamental issues.

Ben FitzGerald is a senior fellow and director of the technology

and National Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. He spelunks in the relationship between

strategy, technology, and business as it relates to national security. You can

follow him on twitter @benatworkdc.

January 28, 2014

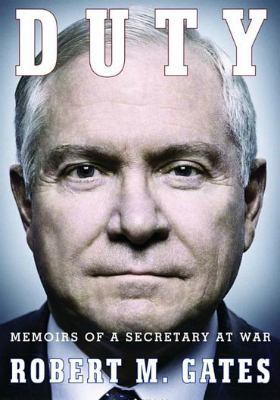

The Gates files (VIIth, and last): Why the Pentagon didn't care about fighting wars

Because, under reforms of the 1950s and

then Goldwater-Nichols, winning wars is not its job.

As my friend and mentor Bob Killebrew

puts it:

"I would just add that by taking the chiefs out of the strategy

business, and making them responsible for building the force, they are no

longer responsible for winning wars (or for strategy) but for the maintenance

and support of their institutions. I suspect this is at least partly why Gates

found such a business-as-usual attitude in the Pentagon, and why you see the SecDef

dealing so much with the combatant commanders and so little with the chiefs.

They are effectively neutered."

Also, just so's youse have it, here's your

last chance to read the review I wrote of Robert Gates's memoir for the New York Times Book Review.

The end.

How to be a platoon leader in 69 steps

On Lulofs' thoughts about war: The good old days you remember? Never happened

By John Haas

Best Defense guest

respondent

Sean Lulofs's "Thoughts about Fallujah" is a welcome

addition to what's becoming a wide-ranging debate over America's strategic

posture at this difficult time in our history. This is a debate we all need to

be having, and Lulofs's sincerely expressed view is an important one to attend

to. It is worthy of our attention if only because it is representative of the

thinking of the vast majority of our fellow citizens.

Lulofs presents us with a jeremiad: Once upon a time,

Americans got the job done; now, "we're just not built to win

anymore." What happened? Don't blame the military -- it is still as

effective as ever, or would be, if only our national leadership wasn't so

"piss-poor." Of course our leaders only become our leaders because

the people have elected them, so they have a share of the blame, too. Our

leaders are more concerned with "public opinion" than doing what

needs to be done to win decisively, says Lulofs. These same people then turn

around and refuse to "hold our leaders accountable for completing the

mission of the war." Of course, that not only the U.S. military, but

militaries worldwide, have routinely blamed the politicians and the people as

insufficiently supportive of their men (and women) under arms should not dissuade us

from considering that, this time, the complaint may be right.

America's military declension, says Lulofs, has been an affair of "the

past 50 years." He appears to hold Eisenhower -- with his willingness to

cut our losses in Korea in 1953 -- responsible for initiating our losing

streak. It's unclear why he begins there. It was Truman, after all, who

"lost" China and went on to reject Douglas MacArthur's victory

strategy in Korea, settling instead for containment in Asia. It was Truman also

who failed to take on the task of driving the Red Army from Eastern Europe,

settling for containment there, too. By my estimate, Lulofs should be claiming

that the United States has labored under a cloud of infamy for at least the

past 70 years. Be that as it may, Lulofs knows who is responsible for America's

decline: Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush, Clinton,

another Bush, and Obama, and all the voters who elected them and then failed to

hold them to account.

Not content to complain, Lulofs points toward a solution, too: If America wants

victories of the sort that gave us "the defeat of the Axis powers" in

World War II -- our last decisive military victory -- it will need to overcome

its "unwilling"-ness to win, rediscover its "willpower,"

and demonstrate "resolve." In other words, international affairs

aren't very different than football games. We may be down for the moment, but

it's still only halftime, and coach is reminding us that if we could only dig

deep, find some gumption, and believe in "true victory" again, the

good old days will come back.

As I said, large numbers of Americans find this sort of analysis thoroughly

attractive: Part Ralph Waldo Emerson, part Émile Coué, part Dale Carnegie,

and thoroughly Hollywood, it's sentimental and naïve talk of the sort we've

used for more than a century to silence our insecurities and convince ourselves

we really can "get out there and shine!" It's also enormously

dangerous. One would think Americans had learned by now that the world isn't as

susceptible as we've wished to "I think I can"-ism.

But, then, what about those good old days? The ones when America won decisive

victories over enemies that only understand "strength and force"?

The first thing to be said is there were precious few of them. Lulofs's notion

of "victory" is at the heart of what Russell Weigley called "the American way of war." Articulated most

forcefully by Douglas MacArthur, it has always been more a dream than a reality -- at times a deadly

aspiration, and also, given our blithe ahistoricism, a myth.

Of the dozens of armed conflicts the United States has engaged in over the

centuries, only three have followed the decisive "victory" script: the

Indian Wars, the Civil War, and World War II. All had unique features that

cannot be replicated by simple force of will.

Each, for example, was perceived at the time as an existential conflict, a zero-sum

game where it was believed that America's future and well-being was at stake. Failure,

we believed, was not an option. (Most historians probably agree with those

estimates, though they might offer some caveats on the Indian Wars.)

That kind of belief, as necessary as it is for sustaining the kind of massive

military efforts required to produce "victory," cannot simply be

willed into existence out of thin air. President Obama can talk until he's blue

in the face, but he will not convince Americans that the United States has an

existential stake in determining which faction of kleptocratic Pashtuns rules Kabul.

These "victorious wars" were massive commitments (well, two of the

three were). Each death in the Iraq War brings immeasurable pain to those

closely involved, but the national commitment to the war is reflected in the

numbers: About one per 20,000 Americans of military age gave the ultimate

sacrifice. One in 25 Americans of military age died in the Civil War; if it

were held today, with losses proportional to our current population, there

would be around 7,000,000 casualties. In World War II, with 12,000,000 men and

women under arms, about one in 160 military age males died, and the financial

burden was huge -- the U.S. government spent more than 120 percent of GDP to

achieve that victory.

Is there any way Americans could come to believe that whatever (considerable)

effort it would take to pacify Ramadi is a rational policy option?

The Civil and Second World Wars each involved an onerous draft, significant

taxes, the reorganization of the private sector around the war effort,

troubling infringements on civil liberties (far beyond merely collecting

metadata), and the mobilization of huge propaganda campaigns to keep the people

in line.

Again, eliminating the most extreme of Sunni Islamists from Fallujah may sound

attractive, but even our most robust effort would still leave only slightly

less extreme Sunni Islamists in charge. I doubt any amount of propaganda will

convince Americans of the wisdom of sacrificing whatever blood and treasure it

would take to secure a more desirable outcome.

If you want a World War II-style victory, you need to put forth a World War

II-level effort. That's simply not going to happen unless we face a World War

II-level threat.

As for the Indian Wars, we will not see their like again, so we should expunge

them from our memories, at least insofar as they beguile us into believing

they're anything like a model for the future. The Indians could offer

courageous and effective resistance on occasion, but the

final outcome was never in doubt. Disorganized (relative to the United States),

out-manned, out-armed, demoralized, and (most of all) devastated by diseases,

the white man was winning the West, no matter what.

I won't elaborate here on the Revolution, 1812, the Mexican War, or Grenada,

but none of them even begin to rise to the level of "decisive military

victories." Indeed, even World War II -- our most iconic war -- didn't end

quite the way we recall. In Europe, it was a Soviet war: Without their effort,

with its massive casualties, eroding the Wehrmacht, it is doubtful the Allies

could have prevailed. Indeed, they might never have gotten off Omaha Beach. In

Asia, even our atomic bombs couldn't compel the Japanese to agree to a truly

unconditional surrender. The threat of Soviet occupation played a much larger

role in Japan's capitulation than we prefer to appreciate.

In sum, the good old days weren't quite what we think, and our recent failures

are more a salutary recognition of reality than a failure to measure up to the

standards of the greatest generation. We have fought the way we've fought for

the past 70 years not because "on or about December 1947, American character changed," but because we are fighting different

enemies with much less at stake. If we ever align the America of our

imaginations with the America that really has been and is, we may find

ourselves waking to a vision that, while less romantically satisfying, might

also find us inflicting less unnecessary tragedy on ourselves in the pursuit of

glories that never were.

John H. Haas

, Ph.D.,

teaches U.S. foreign relations, American history, and the political geography

of North Africa and the Middle East at

Bethel College

in Indiana

.

January 27, 2014

The Gates files (VI): Iran, Pakistan, Doug Lute, and other things that kept him busy

Gates on Iran: "a kind of national security black hole, directly

or indirectly pulling into its gravitational force our relationships with

Europe, Russia, China, Israel, and the Arab Gulf states."

On Pakistan: "I

knew that nothing would change Pakistan's hedging strategy; to think otherwise

was delusional." Later, "I knew they were really no ally at all." (Tom's

question: So how do you leverage a hedging strategy?)

In Afghanistan in

2008, the average size of an IED was 10 kilograms. By 2010, it was three times

that. I didn't know that.

Both Secretary of

State Clinton and Secretary of Defense Gates wanted to fire Karl Eikenberry

when he was U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, but "the ambassador was protected

by the White House." Gates adds that he thought Eikenberry's Afghan policy

"recommendations were ridiculous" and that his "pervasive negativity" permeated

the U.S. embassy.

In something that

might be related, Gates singles out for his disdain Lt. Gen. Doug Lute, the

White House policy coordinator for Iraq and Afghanistan. "Doug turned out to be

a real disappointment in the Obama administration." At one point, he instructed

Gen. James Mattis, then running Central Command, "that if Lute ever called him

again to question anything, Mattis was to tell him to go to hell."

Just a great line:

"I was eating my Kentucky Fried Chicken dinner at home [when] the president

called." That could be the first line of a thriller.

(OK, just one more

Gates item to come.)

Ok, let's talk about the views of NCOs

By

"A. Grumpy Sergeant"

Best

Defense guest grouch

Thanks for asking me as an NCO

how things are going and how we can improve.

Overall I think we're doing okay

in the section. It's good that you introduced yourself to everyone, told us a

bit about yourself, and let us know what your standards and goals for the

section are. I think the most important reason for a successful section or unit

is a healthy NCO-Officer relationship. We both need to know what our respective

roles are and maintain standards (tactical, technical and ethical), and we need

to help each other succeed.

How was my last deployment? If I

may be candid, sir, my last deployment was frustrating. We had a toxic

NCO-Officer situation; as a result the section overall was miserable. Most of

the soldiers left the unit as soon as we returned home and a few left the

military altogether. On the officer's part, he was not very competent in his

branch. And worse, rather than spend time getting up to speed and talking with

his NCOs and lieutenants (most of whom had deployed before and knew some useful

stuff), he avoided interacting with most section members. And because he was

insecure, he didn't hold his NCO to a good standard. I gotta tell you sir: That

was a time I really felt an officer needed to be relieved. And he was a major.

Ultimately I blame his leaders for

tolerating him. Guess they put loyalty over competency, I don't know. Maybe that's

a larger issue with our Army's personnel manning system. Clunky. In World War

II all sorts of officers were relieved.

He also had a bad attitude

towards women and minorities. It's not like he had a poster of Nathan Bedford

Forrest on his wall; it was a subtle (and occasionally nasty) attitude that

affected the way he treated some members of the team. I am tired of having to

give equal opportunity and sexual assault/harassment classes, but the problem

is not just with privates. Anyway, the kicker was, our platoon sergeant had all

the same problems, so it was a perfect storm of toxicity.

To my eternal shame and regret, I

criticized them in the presence of subordinates. Complain upwards, not

downwards, I was taught, and I failed to uphold that standard of

professionalism.

Sir, let me stress the major was

the exception, not the rule. I have served under many good officers -- West

Pointers, former infantry NCOs, ROTC, National Guard, and direct commissions. I

don't assume one category is any worse or better than the other, like some NCOs

do. We have a lot of smart officers who genuinely care about soldiers.

I do think the NCO-Officer

relationship needs to be explained at all levels of leadership. These days it

seems like we learn it in a school for an hour, and then that's it. Of course,

with all the deployments there wasn't much time, but now that they're are

winding down a bit, it's time to do some basics. The NCO-Officer thing needs to

be explained and discussed at all levels -- squad leader, platoon sergeant,

first sergeant, sergeant major, and the same for the Officers Corps.

Sir, I will treat you with

respect, loyalty and integrity. I want our mission and you to succeed, not just

take care of soldiers. I will never again criticize a leader in the presence of

subordinates. I will keep and maintain a leader's book, counsel soldiers in a

timely manner, and know what they're up to, unlike my last platoon sergeant. By

the way, sir, did you know Specialist Jones has a Master's degree in political

science? Yeah, she was a teacher. If we go back to Afghanistan, Sergeant Smith

was a police officer who was born in Turkmenistan. He's a good troop and can

get up to speed quickly on Dari.

Anyway, I don't need

micromanaging, just give me adequate time and resources for a task. By all

means, ask me what's going on, I'll be candid with you and won't give you the

"stay in your lane" comment. Some NCOs misuse that.

And sir, here's that PowerPoint

presentation you asked for. If I may ask a favor, sir, could you not let anyone

else know I know PowerPoint? Thank you, sir.

A "Grumpy Sergeant" is

just that. Grumpy served in the U.S. Army and Army National Guard for 12

years. Grumpy did tours in Iraq and Afghanistan as an NCO and later went back

there as a civilian contractor, which made Grumpy grumpier. These opinions are

Grumpy's alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S Army, the U.S. Army National Guard, the Defense Department, or the U.S.

government.

Tom is again handled gingerly in an official U.S. military pub -- and that's good

In

the new issue of Joint Forces Quarterly,

retired Army Col. George Reed, now at the University of San Diego, writes that, "Former Washington Post journalist and author Thomas Ricks launched a public salvo against the

war colleges in a series of ForeignPolicy.com blogs where he actually called for

their closure, describing them as both

expensive and second-rate. While his criticism is sometimes hyperbolic and

tends to be disregarded by those within the system, he raises some good points

and serves as a watchdog of sorts as evidenced by his recent accounting of

personnel changes that resulted in the reduction of civilian professor

positions at the Army War College."

I

love how I always seem to get such arm's-length faint praise in official

military publications -- Look, I ain't

saying I like the guy, but you got to pay attention to part of maybe one or two

things he says, sir.

As

for closing costly and ineffective military institutions: Perhaps the thoughts do

appear hyperbolic to those of small imagination. Yet in

my experience, what seems unimaginable one year may become reality in another.

For

me, the bottom line is a bit like our discussion of strategy the other day: If

the military establishment begins to feel too comfortable with me, I would feel

I was not playing my role. The founding fathers, in their wisdom, gave us an

adversarial system. If I were bear-hugged by the U.S. military, sought out as a

speaker who would be reassuring and not ruffle any bird colonels' feathers, I

would worry that I was not being sufficiently critical.

So

I will take the uneasiness as a sign of health.

January 24, 2014

If you are comfortable with your strategy, you may not be making very good strategy

The new issue of Harvard Business Review has a good article about how strategy-making

should feel. Usually I am

wary of applying business lessons to military operations, but I do think that

the business world knows a lot about strategy because its leaders have to think

about it every day, while a military leader can slide by for decades without

having to think seriously about it -- or to have his lack of thinking tested by

reality.

Basically, making

strategy should not feel good, avers Roger L. Martin. (The article is titled "The Big Lie of

Strategic Planning," but I don't think that really captures what it is really

about.)

"Fear and discomfort are an essential part of

strategy making," he writes. "In fact, if you are entirely comfortable with

your strategy, there's a strong chance it isn't very good.... You need to be

uncomfortable and apprehensive: True strategy is about placing bets and making

hard choices. The objective is not to eliminate risk but to increase the odds

of success." Indeed, if there is not much risk, there probably isn't much

strategy, he emphasizes: "Strategy involves a bet."

But, you say, you've written strategy documents, and you felt

just fine? Martin suggests that you probably were actually mistaking planning

for strategy. "A common trap," he soothes.

Another insight:

The better your strategy, the shorter it likely will be. "There is no reason

why a company's strategy choices can't be summarized in one page with simple

words and concepts." (Indeed, U.S. strategy in World War II didn't even take up a page.)

The article

reminded me a bit of Michael Porter's classic admonition that, "The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do." Speaking of that approach, there

is a good essay to be written by someone applying that thought to President

Obama's foreign policy: The essence of his administration may be in what it

chose not to do. That's not a bad thing -- I think the same was true of

President Eisenhower's administration. For example, Ike's rejection of the

recommendation of the majority of the Joint Chiefs that he nuke Vietnam. He

wasn't against using nukes, he just thought that ground forces would inevitably

follow, and he was determined not to get involved in another land war on the

periphery of the Communist bloc.

Churchill: The airplane led to the tank

Rummaging around in

early Churchill, I came across his assertion that the military use of the

airplane led to the tank. I hadn't thought about that.

As he explains it,

in World War I, the British use of fixed airfields in Belgium made it necessary

to defend them against German cavalry raids. This led to the use of Rolls-Royce

sedans that had armor affixed to them. Later, armored cars were designed from the

ground up. But then the German cavalry dug ditches across roads to impede them.

This led to the development of armored vehicles with tracks. "The armoured car was the child of the air;

and the Tank its grandchild."

As a general I know

says, all warfare is a lethal version of Rock-Paper-Scissors.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers