Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 62

February 17, 2014

Another reminder that making strategy is often a matter of deciding what not to do

And deciding

what not to do may be the hardest thing of all for the American military to do,

because foregoing something may feel a bit like failure. But

as they say, if it doesn't make you a bit uneasy, it probably is planning, not strategy.

Seymour Hersh offers an explanation of why the Bay of Pigs attack was curtailed

According

to Seymour Hersh's Dark Side of Camelot, the Bay of Pigs attack of April 1961 was supposed to be

preceded, the day before, by the assassination of Fidel Castro. "The assumption

that Castro would be dead when the first Cuban exiles went ashore, and the fact

that he was not, may explain Kennedy's decision to cut his losses. The Mafia

had failed [to kill the Cuban leader] and a very much alive Castro was rallying

his troops." So, Hersh says, Kennedy cancelled the second planned airstrike by

B-26 bombers.

Hersh

also says that after the blunders of the Bay of the Pigs and then the Vienna

summit, at which JFK was verbally slapped around by Khrushchev, Kennedy decided

that he needed to escalate in the Vietnam War to show that he was indeed a

tough guy.

February 14, 2014

Where is the tipping point for America's trust in the military? And are we near it?

By Jim Gourley

Best Defense chief military culture correspondent

Back in 2011,

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Martin Dempsey wondered aloud at a National Guard

leadership conference why the U.S. military had scored the highest among

Americans polled on what institutions they trusted most. "Maybe if I knew

what it would take to screw it up, I could avoid it," he said.

The numbers haven't

wavered outside of statistical error since then. Despite highly unfavorable

public opinion of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, polls by Gallup and Pew back in June showed public confidence in the

military holding above 75 percent. The implication appears to be that no one

blames the military for failing to achieve distinct victory. It leads one to

wonder just what the American people will blame the military for. In the last

year, the military has run some of the biggest governmental scandals this side

of the fiscal cliff. To recap, by service:

Air Force

Two high-profile

sexual assault fiascos, one of which by a sexual assault prevention officer

A massive cheating

conspiracy among nuclear missile officers

Shady handling of pilot deaths in the F-22

The discovery they

lied about the severity of a B-2 crash years ago

The revelations of

the Air Force Academy's secret informant program

Navy

A bribery scandal involving top-ranking officers, high-level

security clearances, millions of contract dollars, hookers, and Lady Gaga

tickets

Nuclear reactor

officers cheating on their tests (what is it about cheating on nuke exams?)

Marines

The incompetence of two generals leading to an attack that destroyed eight aircraft

and killed two Marines.

Potential undue

command influence of a trial by the commandant

Potential

tampering with evidence in a trial by the commandant

Potential cover ups by the commandant

Petty, vindictive

reprisals against the press for covering the commandant's indiscretions ...

probably enacted by the commandant

Army

A $34 million

dollar contract for a building in Afghanistan the military will never use

A recruiting fraud

scandal running up a $100 million tab

The discovery that

a four-star general turned the National Security Agency into the biggest

American diplomatic catastrophe since Dick Cheney.

"Minor"

sexual indiscretion among senior officers is so rampant that it's futile to try

to parse out cases among each service.

Then there's the massive waste occurring in the Defense Department's accounting

systems. But with tens of billions involved, there's plenty for everyone to lay

claim to. Dempsey's question almost deserves a comedic rephrasing. "What's

a military gotta do around here to lose the public trust?" Or is it

perhaps that we've run out of other places to put it, and it's going to rest

with the military no matter what?

The hidden costs of NSA surveillance

What

are the long-term costs to the United States if some in Europe use NSA surveillance

to grab advantage in the Internet market?

On

that study, @kristin_lord tweets, "Revelations of large-scale surveillance

call into question US-centric model of global Internet governance says EU."

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: Two bullets, two legs, one team

By Rebecca

Frankel

Best Defense

Chief Canine Correspondent

On Jan. 19, Sgt. Eric Goldenthal and his dog

Corky were leading a patrol with Green Berets in the Kaspia province of

Afghanistan when they came under attack. Two bullets hit -- one struck

Goldenthal in the leg, another hit Corky in his.

Despite his injury, Goldenthal's only concern

was for his dog: "I just kept asking if he would be alright. I was worried

about his leg," he told the Military Times. The Army handler had

volunteered for this deployment, an "assignment with Special Forces" that began

in September. Their deployment was cut short and just last week both Goldenthal

and Corky came back to the United States. And both walked off the aircraft that delivered them home to Fort

Leonardwood, albeit with the help of crutches and a hot pink bandage.

Goldenthal and Corky, a yellow Labrador, have

been working together for more than a year. Their relationship -- and their

strength as a detection team -- was summed up by their kennel master, Sgt. 1st

Class Brandon Collins:

That day's events speaks volumes. That was

actually the third incident on that day within a few hours. They had already

found multiple explosive devices, thankfully nobody was injured by those

devices. It took three ambushes in order to stop them. Our job is important

because nobody was killed that day, not one person.

February 13, 2014

What does it mean that SpecOps have captured the imagination of the country?

By Adam Johnson

Best Defense guest columnist

I

agree with the notion that American culture

tends to adore the elite Special Operations Forces (SOF) of our day.

After

being commissioned in the U.S. Army, I was initially assigned to the 82nd

Airborne Division at Fort Bragg. One thing I noticed upon my arrival, as my

platoon sergeant pointed out, was that none of the soldiers in our infantry

platoon enlisted into the U.S. Army to become 82nd Airborne Paratroopers -- all

aspired to become Army Rangers, Green Berets, etc., but were unsuccessful in

those endeavors or transferred from other units.

Although

joining a specially selected and well-trained unit is a noble venture, this

trend speaks volumes about the desires of the current generation, my generation.

I vividly recall my platoon sergeant describing a time when young Americans

enlisted to become paratroopers because the maroon beret was considered elite. Maybe that is the

case now, but during my time at Fort Bragg, enlisting to become a paratrooper

seemed to be the next best thing due to an immense desire to work for a

specialty unit "across the street."

"Be

all that you can be" typically meant joining the ranks of the conventional

military in the 1980s and 90s. Both times and culture have changed since then,

and this cultural shift is indicative of the age that we live in. So what

influenced this change? I'd point toward the media.

When

was the last time that Hollywood produced a film about a regular military

unit?... chirp, chirp ... It's been a while. In fact, the only film that I can

recall is Band of Brothers, and its first episode premiered prior to

9/11. Sure, there were other

war and military films released over the last two decades, but they didn't

receive nearly the appeal as those featuring SOF units did. From Lone Survivor (Navy Seals), The Monuments Men (special soldiers

selected to rescue art), Zero Dark Thirty

(Navy Seals), 300: Rise of an Empire

(Spartans), and on and on, recent war movies tend to focus on elite units.

Quite frankly, Americans perceive them as more sexy.

The

media has also been privy to increased levels of questionably classified

information that has intentionally or unintentionally placed SOF units in the

limelight. For instance, I recall the shock when President Obama announced that

Navy Seals conducted the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. The shock factor not

only resulted from the results of the raid, but also from highlighting the unit

that conducted it. Again, an appeal toward a special operations unit.

All of

the media coverage, movies, and attention propagate the glamour of special

operations units and have, in part, influenced this change in heart. However,

the simple fact remains: Not everyone in the military can be special.

Adam

C. Johnson is a former military officer and graduate of West Point. He

currently works at a think tank in Washington, D.C.

Applying Clausewitz to life other than war

The other day it struck me that

Clausewitz's classic observation that war makes even easy tasks difficult also

applies to being depressed.

I wonder if some of his other classic

thoughts can be similarly applied to other aspects of life. None occur to me.

Is there anything else, for example, besides war that is an extension of

politics by other means?

Marine Corps HQ gets some sense, ends its jihad against Marine Corps Times

At least

publicly. It was just bad optics.

And the

commandant should be recognized for doing the right thing, albeit after doing

the wrong thing.

Meanwhile, there is a

good interview with the commandant in the February issue of Leatherneck magazine, the other Marine

journal, in which said General Amos laments "a lack of discipline, personal

standards and appearance" in the Corps.

He also discloses that there are 144 same-sex couples on

active duty in the Marines, of which "less than 25" are Marine-Marine

marriages. (The others are partnered with civilians or members of another

service, he said.) I hadn't seen those numbers before.

I was down at Quantico yesterday. Most of my conversations

were off the record, but I was impressed to see that two senior NCOs are now

attending the Marine Corps Command and Staff College.

The Future of War essays (entry no. 6): Bet on surprises, and get ready to adapt

By Jeff Williams

Best Defense future

of war entry

So we have the question of what will future war look like? In

our look at war, it is difficult to think of a conflict that transformed itself

into an event so completely different from the early notions of all the

combatants at its outset than the First World War. By contrast, the Second

World War -- excluding the development of nuclear fission -- seems in

retrospect more a qualitative refinement of the notions, concepts, and

appliances of war developed in 1914 -1918.

That experience leads one to wonder if a new war will end up

being as much of a surprise how it unfolds as World War I was to its warring

contenders? Will we find that our nation's current stock of weapons and

doctrines are more of a look back into the past, or that they are a discerning

glimpse into the future?

Could our preconceptions about how a future war will evolve

be confirmed much in the same manner as the U.S. Navy's pre-World War II wargaming

which foretold the actual pattern of the Central Pacific offensive, leading to

Japan's doorstep? Like previous wars, will we have time to correct material and

doctrinal shortcomings or will we be stuck with the force we have rather than

the one we need?

In history we find if not explicit answers to our questions,

at least some plausible hints about future war. In the First World War, the

process of rethinking war began with the very first encounter battles in

Alsace. These rethinks did not always lead to success, but nonetheless

continued throughout the war for all sides so that the end of the war was a

very different thing than its beginning. Virtually all the preconceptions and

notions about what war would look like in August of 1914 were violently torn

away and the war took a course of its own, as wars tend to do.

Traditionally, the shifting dynamics of war have played to

America's strong suit of innovation, flexibility and great organizational

aptitude. Yet one cannot help but wonder if in a future war we may not have the

time to regroup and realign our forces to whatever the stark new reality

happens to be.

Will connectivity, networks, and profuse real-time

communications ease the burden on commanders as is intended or, ironically,

will they have the opposite effect? Too much information and too little time

could make for a whole host of difficulties that may dramatically shape the

character of future war.

However, one aspect of the phenomenon of war remains

absolute to this day and will as long as man uses war as an instrument of

policy. The character and the nature of war may change but Clausewitz's dictum

that "the ultimate objective of war is to impose your will upon the enemy" will

remain firm and unchallenged.

If war is in our future, what we will require from our

leadership is, in Clausewitz's fine phrase, "a far-reaching act of judgment" to

appreciate the kind of war they are embarking on and not mistake it for

something other than it is. Not as easy as it sounds, but in the long run

probably the single most crucial consideration the state can make once a

decision for war has been made.

Jeff Williams is a

retired Wall Street type.

February 12, 2014

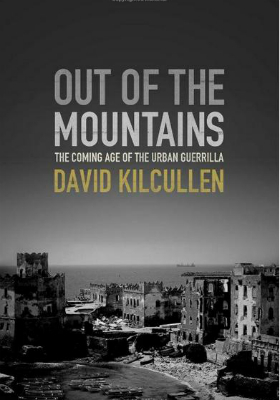

Kilcullen speaks: On COIN going out of style, his recent book, Syria, and more

Best

Defense: What do you make of the whole "anti-COIN" movement?

David Kilcullen:

It's natural for people to ask "What comes after Afghanistan?" and "Was it all

worth it?" There's a legitimate questioning of whether the right decisions were

made in orienting the military to COIN in 2005-6. Also, people are looking at

Iraq these days and wondering whether we lost friends and colleagues in vain.

As you know, I've argued, ever since the first

paper I wrote for the U.S. government back in 2003, that COIN is a last resort

that we should only undertake when some very onerous preconditions have been

met -- to do with the host government's willingness to reform, and its

political viability, and political will at home.

In Afghanistan, in particular, the military has

done all that was asked of it, and much, much more. And yet we're seeing a lot

of difficulty in translating that military success into political stability. It

makes no sense to blame the military for that -- instead we need to ask

ourselves whether we as a nation expect of the military something that it's not

designed (and, in a democracy, not allowed) to do: to forcibly create a

particular political outcome. The military can and successfully does create the

conditions for a stable political situation -- but creating the conditions for

something doesn't guarantee that outcome, as both Iraq and Afghanistan show. In

other words, I don't think the military necessarily has a problem executing

COIN, rather I think the nation may have a problem translating COIN success (or

indeed, military success generally) into long-term political stability.

That may mean COIN is not a viable approach for

us, even when all those preconditions are met. So, I think the jury is still

out on COIN as a military technique (it's not a strategy as such) and therefore

the debate is a valid one -- and the so-called "anti-COIN" movement is a valid

and valuable part of that debate.

BD:

Do you think it has more of a case on Afghanistan than it did on Iraq?

David

Kilcullen: There's a school of thought that says

Afghanistan proves COIN can't work, and another that the Iraq "surge" proves it

can. In my view, each side is overstating its case -- in Iraq, we did a lot of

things that weren't in the COIN manual, and much of the turnaround began (for

example, with the Marines in Anbar, or certain units in Baghdad) in 2006,

before the COIN doctrine came out. Also, the Awakening (the uprising of the

Iraqi tribes against al Qaeda) was a huge part of it, so there was much more

going on than just a new COIN doctrine. There's a correlation in time and space

between success on the ground and introduction of COIN doctrine, but

correlation is not causality.

In Afghanistan, by contrast, when General

McChrystal was appointed in 2009 and told he would be executing a "fully

resourced COIN strategy," he did a detailed analysis based on COIN doctrine and

decided he needed something like 80,000 additional troops to do it. He was told

to not even ask for that amount, so he requested 40,000, and in the end got 30,000

extra troops for only 18 months, with about another 7,000 added later during

the surge. So, vastly fewer troops than COIN doctrine requires, for a much,

much shorter time -- the doctrine talks about campaigns lasting 10-15 years,

not 18 months. We've never had anything close to the doctrinal troop strength

or timeframe that COIN calls for.

So, saying that Iraq proves that COIN works is

a gross oversimplification, and saying Afghanistan proves it doesn't work is

just plain wrong: If you give the patient half the dose for one-tenth the time,

and she still gets sick, you can't then say that proves antibiotics don't work....

Likewise if you give the campaign half the troops that the doctrine calls for,

for one-tenth of the time, you can't say the campaign proves anything much

about the doctrine.

BD:

A larger question: What do you make of intellectual fashion in military

culture? Why do ideas seem to take hold with such ferocity and then are

discarded before they are half-understood?

David

Kilcullen: The military is skeptical of untried ideas

for good reasons: They can get you killed. Picture yourself climbing a cliff,

hauling yourself up from hand-hold to hand-hold, and some good idea fairy

rappels down and hangs comfortably next to you, offering helpful new

rock-climbing techniques. You're not going to be too receptive. You'll be like,

"Hey man, just let me just get to the top of this cliff and then we can discuss

it." Troops in combat are like that -- they want to be shown that something

works before they discard proven techniques built on lessons that are literally

written in their friends' blood. On the other hand, when people realize

something really does work, they embrace it enthusiastically because it has an

immediate, life-saving effect. I saw this first-hand with units in both Iraq

and Afghanistan, who were initially, very properly, skeptical of COIN until

they saw it could work, and then they suddenly "got religion."

More broadly, there's definitely a pattern of

military fads and fashions, just like in other human endeavors. Before COIN it

was "Transformation," before that the "Revolution in Military Affairs" and the

"System-of-Systems," and so on. Right now there's a fashion to reject

everything of the last decade and focus on "returning to real soldiering." But

there's also a groundswell of anger and disillusionment at the junior officer

and senior enlisted level. That's actually positive, because real innovations

in military thought come not from academics and generals or admirals but from

angry junior leaders with combat experience.

Think of the Western militaries after the First

World War -- cavalry generals like Douglas Haig were slapping each other on the

back, saying "trench warfare worked;" it was the more junior officers -- guys

like Billy Mitchell, Liddell Hart, Manstein, Guderian, Rommel, Tukhachevsky -- who

looked at the hell they'd just been through and said, "There has to be a better

way." And it was from that anger at the junior levels in the 1920s that ideas

like Blitzkrieg and Strategic Air Forces and Maneuver Warfare came about.

Likewise, it was junior Marine officers -- lieutenant colonels and below -- in

the 1930s, in a time of real resource constraint with the Great Depression, who

came up with innovations in amphibious operations like the Higgins Boat, and

from that came, in part, MacArthur's successful island-hopping campaign in the

Pacific, and the Normandy landings. There are a lot of angry, skeptical people

out there now, at that same lieutenant colonel and below level, and we have to

listen to them because it's from these guys that the new ideas will come.

And as part of that, we have to be ready to

move away from what we think we know -- including COIN. COIN, in its 21st

century reincarnation, was an adaptation we made, under fire, to fix a problem

we should never have gotten ourselves into in Iraq. To the extent that it

hardens into some kind of eternal dogma, we need to be very wary of it, because

the next big challenge might be an insurgency, but it might not. Even if it is

an insurgency, it may or may not be amenable to the techniques that are in the

current COIN doctrine.

Part of this is what I discuss in my latest

book, pointing out that in a future megacity, population-centric COIN

techniques -- as written in FM 3-24, anyway -- are simply not going to work,

because of the scale. So we need to think of new approaches.

BD:

What motivated you to write

your most recent book

?

David

Kilcullen: In part, it was the experience of being out

in Afghanistan, where I've worked on and off since 2005, and realizing that

much of the violence there is created by economic, tribal, and

contracting-driven patterns of conflict, and very little of it is directly

connected to Islamist extremism, the Taliban, al Qaeda, and so on. In an

earlier book (The Accidental Guerilla),

I showed how a lot of the people we fight are fighting us not because they hate

the West, but because we're there, in their face, looking for a completely

different set of enemies who hide in their societies. In this book I've tried

to lay out some ways of thinking about these conflicts that make more

real-world sense than just thinking about "terrorists" or "insurgents."

But as I researched the book, going to places

like Colombia, Somalia, Libya, Sri Lanka, and looking at megacities like Rio

and Dhaka and Mumbai and Lagos, I realized that while we've had our heads down

chasing bad guys around Iraq and Afghanistan, the world has changed a great

deal. For starters, we're looking at 3 billion new urban-dwellers by mid-century,

virtually all of them in developing-world coastal cities: That's the same

number of people it took all of human history to generate, across the entire

planet right up until 1960. And these people are connected, electronically -- with

each other and with the broader global system -- to a radically unprecedented

degree.

So I ended up writing about future cities -- not

offering answers, but trying to ask some questions about urbanized conflict in

the generation after Afghanistan. And patterns like coastal urbanization,

population growth and -- most importantly, and the only really new factor -- massively

expanded electronic connectivity turn out to have a major impact on that future

environment.

Though, obviously, my start point is guerrilla

warfare, I end up arguing that there's a paradox here: On the one hand, history

teaches us that the military is going to get dragged into messy irregular

conflicts, and those conflicts will increasingly be in highly connected coastal

megacities. So if you're in the military, you'd better be thinking about that.

On the other hand, there never has been, and never will be, a purely military

solution to any of these problems. Militarizing them, sending the military in

to "solve" something that may be insoluble, is a really problematic approach.

Particularly in a lot of the places where I've worked, sending the local

military (or heavily armed police) into someone's neighborhood doesn't make

them safer -- it just offers them lots of attractive new opportunities to get

shaken down. So I suggest some ideas drawn from urban design, around community

mapping, participatory development, urban metabolism, and co-design, which the

evidence suggests are likely to work better.

COIN in megacities, though, is a really, really

bad idea -- you could lose an entire division in some of these new coastal

cities and most people who live there wouldn't even know it was there. There's

an issue of scale here that has never really been faced in COIN theory, which of

course was designed primarily for rural agrarian conflicts in the mid-20th

century. There will certainly be future insurgencies in megacities -- but COIN

as we currently understand it may not be the right way to counter that threat

in urban fighting.

BD:

Speaking of urban fighting, what are you thinking about Syria? Do you see a way

out?

David

Kilcullen: Unfortunately, no. Syria is, first and

foremost, a human tragedy of immense proportions. Over the past year we've seen

a massive deterioration in human security, with a lot of international

humanitarian assistance not reaching the most vulnerable populations, and not

much of an end in sight. It's what we might call an escalating stalemate: no

prospect of outright victory for either side, little prospect for a negotiated

peace, and yet violence levels that keep ratcheting up. For ordinary Syrians,

it's tragic.

Geopolitically, we're also seeing some

extraordinarily negative effects from the conflict -- it's a key factor in the

rise in civilian casualties in Iraq, for example, and has also destabilized

Lebanon, parts of southern Turkey, and several other neighboring countries. It

has revived al Qaeda in Iraq and given it new strength. Less negative but

politically problematic, we've seen the emergence of a de facto autonomous

Kurdistan across northern Iraq and northeastern Syria. A few weeks ago, the

Kurdish Regional Government began exporting oil without approval from Baghdad,

while civilian councils in northeastern Syria call themselves the councils of

"western Kurdistan."

Equally transformative is the sheer pace and

scale of foreign fighter flows into Syria, which dwarf anything we saw in Iraq

by a factor of 10 or more. Those fighters come from North and West Africa, from

across the Middle East and Central Asia, and of course from the European Union,

which effectively has a land border with Syria through Turkey. And then there

are the Chechens and Daghestanis who've come to Syria to fight a Russian ally

and train for jihad. This will have a long-term regional, and possibly global

effect that's only now starting to become apparent.

Bottom line, I think the conflict has a long

way to run, it has some troubling spillover effects, and little prospect of a

peaceful resolution any time soon.

BD:

Do you have any major lessons learned from Syria?

David

Kilcullen: Yes, lots -- and in fact Caerus Associates is

publishing its key research findings this week, based on a study of how the

conflict has developed in Aleppo over the past several months. Beyond what I've

already mentioned, one observation is that we're seeing a whole new class of

Salafi jihadist groups emerge in Syria, with Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic

Brigades. Unlike their rivals (the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Shams, ISIS,

which is basically al Qaeda in Iraq, version 2.0), we've seen these new groups

learn from the experience of being defeated in Iraq in 2008-09 and develop a

set of humanitarian, governance, and administrative capacities that they're

using to good effect to build support from the population. Meanwhile ISIS has

been following the same old Iraqi script of beheadings, bombings, kidnappings,

and torture -- alienating people to the point where al Qaeda Central just

disowned them for being too extreme. Ouch.

BD:

What is next for you?

David

Kilcullen: Well, it's nearly four years since I founded

Caerus Associates, and the company has grown into a small but capable R&D

firm that works across Africa, Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East on

some pretty sophisticated modeling and analysis of difficult and dangerous

environments. Caerus works for NGOs, international organizations, aid agencies,

and corporate clients, and of course for governments including the U.S.

government. Virtually none of that is my doing -- I've been lucky enough to

gather a really capable leadership team at Caerus, and our research and field

teams have achieved a level of talent and capability I could never have

imagined.

As a founder it's always difficult to know when

to step back from your start-up and let the company blossom and develop beyond

your original vision. This year, in part because of my impending U.S.

citizenship, I've decided it's time to do that, so we've consolidated the two

halves of the company (R&D and field research) under Dr. Erin Simpson as

CEO. Erin has done an outstanding job leading our U.S. government R&D

company for the past two years, and I have great confidence in her and the

management team to take this to the next level.

I plan to be around to support the team without

telling them what to do or how, but my focus is shifting to academic writing

and teaching, and working with philanthropic foundations in the United States,

Africa, and Latin America. I'm also working with a couple of new start-up

companies, one in the United States and one in Europe. It all keeps me running

around madly from place to place...

BD:

What is your favorite book of the last year?

David

Kilcullen: Hmmm, that's a tough one, so many great books

came out in 2013.

I particularly enjoyed Stig Hansen's new book Al Shabaab in Somalia,

which paints a detailed picture of how al-Shabab is evolving as African Union

peacekeepers push them out of major cities, and they begin to go regional

across Africa.

I'm also halfway through two fascinating new

books -- Salvadoran writer Oscar Martinez's The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging

Narcos on the Migrant Trail, which chronicles

his underground journeys with illegal immigrants across Central America's

people-smuggling networks, and Ian Buruma's wonderfully written Year Zero: A History of 1945,

about the reconstruction and stabilization challenges, and the humanitarian

catastrophes, of the end of World War II -- a valuable reminder that not much

of what we're dealing with today is new.

BD:

Thank you.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers