Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 59

March 3, 2014

Ukraine: Call me a crazy optimist, but I think that in the long run, Putin and his kleptocratic pals will be the losers here

I spent a good part

of the weekend reading various punditry on the Ukrainian situation. The Russian

takeover of Crimea is awful, but I do believe that Putin's Russia will be the long-term loser in this situation. If the

Europeans needed a reminder of why they need NATO, they just got it. And I think they do need such a notice every couple

of decades or so that the purpose of NATO is to keep the Americans in, the Russians

out, and the Germans down.

As one smart officer

I know put it yesterday, "Putin remains what he

always was -- an opportunistic, self-promoting, KGB lieutenant colonel who

believes that he is some sort of great statesman. He rules Russia by co-opting

as much of the population as he can into his preferred game of corruption,

graft, cons, and bribes and by intimidating the rest to keep quiet. His

brazenness is belied by his vulnerability -- and by the vulnerability of

oligarchs gathered around him. The sad truth is that he and his clique are

destroying Russia more surely and rapidly than any action that the US and our

allies (or, for that matter, China, Muslim separatists, Ukrainian nationalists,

etc.) ever could."

Bottom line: No,

this is not 1914. Nor is it 1938. Lots of panicky customers out there selling

the West much too short. This just may be the last gasp of a sick, Ottoman-like

empire. Let's not get too flighty.

On how to respond to

Vlad the Invader, I am, with Garry Kasparov, a "banks not tanks" guy. The way

to inflict genuine costs on Putin and his buddies is with a financial squeeze.

This situation is a challenge to the European Union to step up and do the right

thing: Stick it to the Russian kleptocracy. We can help by providing

information and by shining a bright light on what Russia is doing.

This is also a real

opportunity for the WikiLeaks/Snowdenistas to leak material damaging to the

Russian oligarchy, like who has all the money and how they get it out and where

it is now. What a wonderful way to bring together the leftist information types

and the rightist hawks.

Cohen: Why ex-Defense Secretary Gates was wrong to publish that memoir now

Some little grasshoppers will remember that I am a fan

of the memoirs of Robert Gates. But my friend

Eliot Cohen argues powerfully in the Weekly

Standard that Gates was wrong to publish them now:

The publication of this memoir now is a breach of

faith and a violation of propriety that is hard to understand. If Gates

believes that Obama is a disastrous president, surely he should have published

this book in 2012, when it might have influenced the presidential election. If

he is merely (and appropriately) contributing to our understanding of history,

he should have waited until Obama leaves office. If he thinks he can change the

president's modus operandi and worldview by publishing it now, he is deluding himself.

Tom again: This is a strong

argument, but I am not sure if the last sentence is correct. I think Gates

could have an influence on Obama's behavior, especially his tendency to favor

the advice of political hacks over foreign policy experts.

NB: Unfortunately, money-losing

unprofit magazine does not provide link.

Not making this up: Marine sex assault lawyer faces charge of bad butt touching

The Marine Corps

can't catch a break these days. One of their top lawyers dealing with sex

assault issues now faces a charge of inappropriate butt touching. How do they select these guys?

February 28, 2014

The Future of Warfare (12): It's coming to a neighborhood near you -- the homeland

By Major Daniel Sukman

Best Defense future of war entry

A lot has been written on the future of warfare and the inevitable

rise of unmanned and autonomous robots and other systems on the battlefield. This

will prove to be correct, as we have already witnessed the first wave with the

advent of drone warfare over the last decade. What will be different in the

future is the location of warfare, specifically for America. Taking in the

second-, third-, and fourth-order effects of drones and other lethal autonomous

systems, future warfare will increasingly occur in the homeland.

During the Vietnam War and the recent conflicts in Iraq and

Afghanistan, America's adversaries have learned that the most effective way of

attacking the U.S. strategic center of gravity (the support of the American

people), has been through attrition warfare. The more soldiers, airmen, sailors,

and Marines that appear on television or come home in a body bag, the lower

support for action overseas becomes. Drone warfare, and the introduction of

unmanned autonomous systems on the battlefield, be they supply trucks or tanks,

will remove the danger to American servicemembers on the battlefield. Adversaries

will look for asymmetric ways to attack American servicemembers, and the most

effective way to do it will be in the United States.

America's adversaries, although they will continue to look for

devastating terrorist-type attacks as we saw on 9/11 or even at the Boston

Marathon, will look for "legitimate targets" outside air bases in

Nevada from which drones are being operated. They will seek to target

headquarters of contracting companies such as Booz Allen or Blackwater (or

whatever they are called now). The attacks will not occur on the bases, but

rather when targets of opportunity present themselves. A drone operator

stopping at the local 7-11 after a shift is one example of many.

The targeting of individuals away from the battlefield is not new

to warfare, in fact it has been demonstrated in the past few years with the assassination

of nuclear scientists in Iran. There is no reason to think that our enemies

won't adopt these types of tactics to target individuals in the homeland. This

will be different from what we have seen from al Qaeda, in that nations that

the United States engages in hostilities with will look to conduct these

asymmetric attacks. They will not be limited to non-state actors.

The U.S. military must prepare for the warfare of the future, and

can do so in a number of ways. First is to ensure that soldiers overseas still

are at risk on the battlefield. We must ensure that our warriors in uniform are

viewed as warriors in the eyes of our enemy. Second, we should look at the

force protection measures we offer those in uniform within the homeland. Historically

a law enforcement-type mission, those that are conducting combat operations

from within the continental United States need to have the situational

awareness that in the future they may become legitimate targets, not only in

the eyes of our enemies, but in the eyes of the broader international

community. If today a member of the Taliban were to ambush a drone operator on

a Nevada highway, could he make a case in court that he is a legitimate actor

on the battlefield and should be considered a POW with all the rights and

protections that come with that status?

The U.S. military must form partnerships and work with law

enforcement agencies within the United States in the area of protection. This is

not a future in which the United States abandons the principle of Posse

Comitatus, rather it is a future where law enforcement has a larger and more

proactive role in America's conflicts.

War in the homeland is a scary thought. Outside of major terrorist

attacks, for the most part the homeland has been secure since the War of 1812. Although

we continue to fight the War on Drugs, the War on Poverty, the War on the

Middle Class, and the War on Christmas in the homeland, the American Way of War

is to play away games against other nations. If we are not careful in the way

we pursue unmanned and autonomous systems, that piece of the American Way of

War may change forever.

Major

Daniel Sukman, U.S. Army, is a strategist at the Army Capabilities Integration

Center, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command at Fort Eustis, Virginia. He

holds a B.A. from Norwich University and an M.A. from Webster University. During

his career, MAJ Sukman served with the 101st Airborne

Division (Air Assault) and United States European Command. His combat

experience includes three tours in Iraq.

This article represents the

author's views and not necessarily the views of the U.S. Army or Department of

Defense. And yes, this is

his second entry

in

the contest.

If Iraq was in Ukraine, Thailand, or Venezuela, we'd be paying attention

But no one here cares

that dozens of people are getting killed there on an almost daily basis. We've moved on.

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: Postcard from the past, a war-dog wedding

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

In 1976, Air Force handlers Charlotte Sandwick and Keith

Hyland were married at the chapel at Yokota Air Force Base in Japan. It was a

war-dog wedding through and through -- their nuptial party was made up of

fellow handlers of the 475th AB Wing Security Police and in attendance, of

course, were all their dogs.

Though it's just a snapshot, this photo (featured on a

series of dog-handler Facebook pages this week), and its headline -- "Dogs

go to marriage" -- were irresistible. Both the bride and groom were Air

Force handlers in the 1970s, airmen first class. We talk a lot here about how

the military dogs tight-knit community rallies in times of need and remembrance,

but we'd be remiss not to showcase the happy occasions too.

Hat tip: Military Working Dogs FB group, The U.S. War

Dogs Association

February 27, 2014

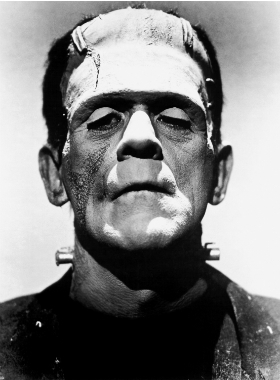

FoW (11): Enhancing human performance

By Daniel P. Sukman

Best Defense Future

of War entrant

One of the primary elements of military research and

development is how to enhance human performance in combat, from better

equipment, weapons with longer reach, lighter loads to carry, better

physiological preparation, to all-encompassing physical enhancements. Today,

with advancements in science and technology, the U.S. military is at a crossroads

in determining how far to go in considering how to attain soldiers, airmen,

Marines, and sailors who can physically outperform our potential adversaries. To

borrow from the Olympic motto, the future of war will demand "faster, stronger,

and higher."

The limits of enhanced human performance needs to be where

the enhancements negatively effect a person the day after they leave the U.S.

Military. Although the military is a profession, unlike doctors and lawyers,

serving as a soldier does not encompass the entirety of adulthood. Most servicemembers

will leave service in their early twenties, and even those who put in 20-30

years of service will still depart with half a lifetime remaining on earth. The

complexity of the issue revolves around the argument that although certain

human enhancements may negatively affect your life after the service, it may

extend your life so you reach that point. Looking at the different ways we can

influence the human body to survive and win on future battlefields is the next

step in the evolution of the American way of war.

To meet the demands of the future battlefield, the means of

altering the human body and mind that we as a society should find acceptable

needs to be examined. To highlight the complexities, I offer the following

"lists of things" that enhance human performance, be it in the office, cockpit

or sports field. Think about what is considered "legal" what is "ethical" and

why.

Coffee, soda,

Snickers bars, amphetamines, Ritalin

Cold medicine, Human

Growth Hormone (HGH), performance enhancing drugs (PEDs), anabolic steroids,

pain killers

Vaccinations, Tommy

John surgery, Lasik eye surgery, Blood Doping/EPO, training at high altitude

As you look at each list, you can see a variety of methods,

be it ingestion of caffeine, or a surgery that physically alters your god-given

natural abilities. Some methods on the list are banned by the Olympics (cold

medication) and professional sports (deer antler spray) but remain legal for

the general populace, others are encouraged (Tommy John surgery), while others are

illegal to obtain on your own. Some of the items, such as coffee and soda, are

even banned by some religions due to the caffeine within those drinks.

An unspoken truth is that soldiers, like athletes, do not

have to be convinced to take performance enhancing drugs. Legions of staff

officers start their day with pots of coffee followed by the nicotine rush

contained in dip and other smokeless tobacco products. Similarly, the use of

drugs such as Ambien to promote sleep in stressful situations or when travelling

long distances is widely used in the armed forces. Pilots have a long history

of taking "no doze"-type pills and even amphetamines when required to fly long

distances. A "Red Team" member worth his salt would do well to find an

asymmetric way to limit coffee to staffs and energy drinks and dip to young

soldiers.

Sleep plans, or as those in the military call it "fatigue

management," is a vital part of any combat mission planning. In the 2012 Marine

Corps S&T Strategic Plan, planning for sleep is as vital as "planning for

food, fuel, ammunition or other essential logistical supplies." There may be a

risk of addiction that must be balanced, however, with the pharmaceutical

agents that exist to enhance the effectiveness of sleep during combat. If those

drugs enhance the decisions of leaders, or allow soldiers to operate at higher

altitudes, and if that, in turn, will save U.S. lives in battle, those methods

should be pursued.

In the sport of cycling, taking Erythropoietin (EPO)to raise

red blood cell counts, thus improving oxygen delivery to the muscles, is

officially banned (as Lance Armstrong is well aware of) but it is quite legal

to train at high altitude or sleep in a hyperbaric tent, which achieves exactly

the same result physiologically. Should the U.S. military, in preparation for

combat in places such as Afghanistan take EPO, or limit itself to train in

areas of high altitude? Why not allow soldiers in combat to take EPO if it will

enhance their performance and increase the odds of completing missions and coming

home alive?

Aside from biological enhancements, actual physical changes

to servicemembers can be envisioned in the future. Today we are able to replace

lost limbs on our wounded warriors, but can we add to or change (permanently)

physical characteristics of our servicemembers to provide them with one-on-one

overmatch against potential adversaries? If we can change the skin composition

to be tougher and more resistant to bullets and shrapnel, should we do so? Of

course, as Patrick Lin noted in his article "Could

Human Enhancement Turn Soldiers into Weapons that Violate International Law? Yes" in

the January 2013 issue of The

Atlantic, doing so might embolden our adversaries to engage in harsher

tactics and procedures when fighting U.S. forces. Sleep deprivation may not

torture you if you physically don't require sleep.

Enhancements in human performance, be it physical or mental,

can occur long before it becomes a necessity due to a catastrophic injury

incurred in training or in combat. If technology would allow for soldiers to

have surgery to increase their running pace, or for a plate to be inserted into

the knees or back that makes a parachute landing fall easier, or carrying a 70

pound rucksack not all that difficult, why not perform that surgery "left of

the boom," so to speak.

Mental enhancements can be a necessity in the fast-paced

ever-changing complex world of combat. This complex world demands rapid

decision-making more often than not with imperfect information and

intelligence. Should the use of certain drugs to focus the attention of

decision makers (e.g. Ritalin) and better prepare forces for combat be

encouraged? I am not advocating making military leaders walking drug stores,

but if more focused mental preparation and planning of combat can save lives,

why not offer the best enhancements modern science can provide?

The question becomes, should servicemembers be required to

risk their long-term health in pursuit of short-term physical and mental

enhancements. Professional athletes are largely prohibited from doing this, hence

the ban on PEDs and anabolic steroids. However, soldiers, Marines, airmen, and

sailors are expected as part of their service to put both their health and

lives at risk. As Clausewitz wrote,

war is violence." The future of warfare will require stronger, faster soldiers

who have more endurance; however we must be careful not create a new generation

of East German Olympic swimmers.

As the science and technology of warfare continues to

proliferate around the world, the assumption should be made that adversaries of

the United States and our allies and partners will not limit themselves with

ethical considerations in how they enhance the performance of their

footsoldiers. U.S. soldiers will not go into combat high on khat, but should

acknowledge that certain adversaries in Africa may be as we saw in Task Force

Ranger in 1993. Performance enhancing drugs, stimulants, and other narcotics

will certainly be used by our adversaries, and we should develop training and

strategy that accounts for this. We must also prepare for adversaries who have

access to advanced technologies who may use nanotechnology, or even

pharmaceuticals such as Adderall to increase their cognitive performance.

Risk of each human enhancement must be a paramount factor in

considering what we can do with servicemembers. For example, steroids can cause

terrible health problems, like liver and kidney failure, while the risks of eye

surgery are much lower both in terms of probabilities and effects. By this

standard, we accept greater risk in the now, in that performance will be

reduced in warfare; however the risk is greater of catastrophic injury or death

when involved in combat operations.

What side of the risk coin

should we as a military profession find easier to accept?

Major Daniel Sukman, U.S. Army, is a strategist at the Army

Capabilities Integration Center, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command at

Fort Eustis, Virginia. He holds a B.A. from Norwich University and an M.A. from

Webster University. During his career, MAJ Sukman served with the 101st

Airborne Division (Air Assault) and United States European Command. His combat

experience includes three combat tours in Iraq. This

article represents the author's views and not necessarily the views of the U.S.

Army or Department of Defense.

Tom note: Got your own views of the future of war?

Consider submitting an essay

. The contest remains open for at least another few weeks. Try to keep it

short -- no more than 750 words, if possible. And please, no footnotes or

recycled war college papers.

Kicking the Guard out of attack helos is part of a set of good moves for the Army

By Maj. Crispin Burke,

U.S. Army

Best Defense guest

columnist

Make

no mistake: Army Aviation will feel the effects of sequestration and be forced

to cut back, along with the rest of the Army. However, if the Army concentrates

on putting trained and qualified people

in the right organizations, armed

with the right equipment, Army

Aviation can weather today's budget cuts, and move forward into the 21st century.

A

bold new proposal would do just that -- completely revamping the Army's

aviation brigades in both the active and reserve components by divesting some

aircraft, reallocating others, and by integrating Unmanned Aerial Systems

(colloquially called "drones") with manned aircraft.

According to the proposal, recently reviewed by

the secretary of defense, the Army would retire its entire fleet of single-engine

helicopters, including 368 OH-58D scout helicopters, 228 elderly OH-58A/Cs, and

182 TH-67 trainers -- a grand total of 778 aircraft. To compensate for the

losses, the Army would radically re-shuffle its remaining dual-engine aircraft

-- replacing the active-duty OH-58 losses with AH-64 Apache helicopters drawn

from the National Guard and Reserve, and by moving many of the newly-acquired

LUH-72 Lakotas to the training role.

The

plan, of course, is not without its detractors. According to Politico, fifty state governors voiced their dismay over the loss of the

Guard's Apache helicopters in a letter to President Obama. Indeed, each

aircraft lost represents not just a machine, but an aircrew, a team of

maintainers, and plenty of jobs, livelihoods, and families affected.

Moreover,

the loss of the OH-58D is certainly a bitter one. But budget cuts are coming,

and Army Aviation is left with few alternatives, following the failure of both

expensive replacements (Comanche in 2003), and off-the-shelf options (Armed Recon Aircraft in 2008 and Armed Aerial Scout in 2013). It's

important to note, though, that reconnaissance involves more than just aircraft

-- it's trained and qualified people, and fortunately, OH-58 pilots are among

the most experienced in the Army. The OH-58 community has an incredible warrior

ethos, and despite the loss of a beloved airframe, their expertise will matter most. We shouldn't fear aircraft transitions

-- after all, were we a less capable force when we transitioned from Hueys to

Black Hawks, or from Cobras to Apaches?

Of

course, once Army Aviation gives people the right training to do the job, it's

time to focus on the organizations --

perhaps the most audacious step in the way forward. The Army National Guard

would face some difficult challenges, particularly as its Apache pilots

transition to a new aircraft (the UH-60 Black Hawk), and with it, a new

mission.

Fortunately,

Black Hawks are far more useful for homeland defense and providing defense

support for civil authorities (Title 32). The Guard would be receiving 111 of

them to offset the loss of the Apaches. Moreover, the Guard would still be able

to provide Title 10 to overseas fights through its remaining fleet of Black

Hawks and CH-47 Chinooks. In fact, proportionally speaking, the Army National

Guard would suffer less than the

active component, in terms of total aircraft loss (just 17 percent of the Guard

force, compared with to nearly 30 percent of the active component).

With

regards to the active component, the Army has also taken the unprecedented step

of pairing unmanned aircraft with manned aircraft. Each newly-formed Attack

Reconnaissance Squadron would consist of three troops of eight AH-64 Apaches

apiece. Each troop, in turn, would be augmented with a platoon of four Shadow

drones, many of which would be culled from deactivated BCTs. Each aviation

brigade, additionally, would receive a company of 12 armed Grey Eagle UAS, a true

medium-altitude, long endurance (MALE) airframe. It's an

acknowledgement that unmanned aviation is here to stay -- manned and unmanned

crewmembers will train, deploy, and fight alongside one another on a permanent

basis. In fact, the Army is arguably far ahead of the other services in this

regard.

Once

we have the right people, placed in the right organizations, the equipment falls into place. If all goes

as planned, the rotary-wing community will be an entirely dual-engine force. Students

will begin their aviation career in the LUH-72 Lakota, recently acquired by the

Army, with a proven track record in medical evacuation and law enforcement.

Old-timers

may lament the Lakota's glass cockpit, dual engines, and GPS, but the fact of

the matter is every single combat aircraft in the conventional U.S. Army's

inventory has these features. We need to seriously rethink what we should

expect from students in flight school. Whereas, 10 years ago, the use of GPS

would have been verboten, today, it's

a necessity, as GPS approaches dominate the instrument routes. Moreover, while

students may no longer perform autorotations all the way to the ground, they'll

have to learn to identify engine malfunctions in a multi-engine aircraft, a

skill which takes a considerable amount of time to learn as students progress

to new airframes.

All

told, reducing and simplifying the Army Aviation rotary-wing fleet -- from

seven airframes to four -- will save the community billions of dollars over the

years, and we'd be a much more modern and powerful force for it.

The

choice is clear -- proven people,

strong organizations, the right equipment.

Major Crispin Burke is

a serving U.S. Army officer. Direct all angry comments towards his Twitter

account, @CrispinBurke.

The Future of War (no. 10): Let's figure out how not to get into one with China

By Sean Kelleher

Best Defense future of war entry

Several recent commentaries on

the emerging Air-Sea Battle doctrine have emphasized the escalatory risks of

launching massive conventional attacks against an adversary's home territory

when the adversary has a range of retaliatory means at its disposal, including

nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles (see the Diplomat, USNWC). These risks deserve close consideration,

but they are not uniquely characteristic of Air-Sea Battle, rather they are

endemic to any strategy aimed at achieving decisive victory.

The American military puts on its

best performances when it goes for the jugular: Grant's multi-pronged invasion

of the Confederacy, Winfield Scott's march to Mexico City, and the initial phases

of the 2003 invasion of Iraq are all model operations. This record is

consistent with the historical experiences of other armies; Alexander marched

into the heart of the Persian Empire, Genghis Khan had no patience for borders,

and Napoleon won most of his victories in other peoples' countries. The attack

component of Air-Sea Battle fits nicely into this pattern; massive cyber,

electronic, air, and missile strikes paralyze an opponent's capacity to

coordinate its forces, followed by attacks on now isolated targets. It aims for

decisive victory in multiple domains of warfare and, assuming appropriate

intellectual and material investments, the Pentagon has a good chance of

converting the nascent idea into an operational reality (useful

documents: DOD-JOAC, CSBA 1, CSBA 2, Danger Room).

One may reasonably ask whether

the probability of total war with China is high enough to justify a massive investment

in the war-fighting tools that would be needed to win it. However, if we assume

that the investment is justified, Air-Sea Battle is a sound idea. Yes,

there are escalatory risks, but as long as the military infrastructure in

China's coastal provinces is central to the PLA's operations, Washington will

have to be prepared to destroy it. There is no polite way to bomb another

country, and, in my decidedly non-expert opinion, much of the criticism of

Air-Sea Battle is not about the doctrine itself, but about the wisdom of

fighting China.

The most salient criticism of the

doctrine is not its expansive scope, but its limited purview. Basing our

fortunes on an aggressive naval/air/cyber strategy assumes that a U.S.-China

conflict will not involve land battles in Asia, or attacks in the Eastern

Pacific. But what if we have to help Russia protect Siberia's resources from a

Chinese invasion, or if we need to evict PLA soldiers from Taiwan and Okinawa? Also,

what if Chinese submarines launch cruise missiles against the West Coast, while

ballistic missiles reign down on Pearl Harbor? Faced with a conflict akin to

the World Wars, Air-Sea Battle would have to be combined with other operational

concepts to create an effective strategy.

At bottom, if current economic

and military trends persist for several decades, and Washington and Beijing go

to war in the grand style, there will be a dramatic risk of escalation. But the

origin of the risk will be the conflict itself, not the strategies used to

fight it (for economic projections, and U.S.-Soviet Union comparisons, see

these posts: 1, 2).

This author, adverse to expending

vast intellectual and material resources on a perpetual arms race, let alone

living through World War III, favors radical diplomatic initiatives to develop

a deeply cooperative relationship between America and China. I have proposed

some ideas on this matter in earlier posts (here and here), but on further reflection I suspect that to break out of the security

dilemma, the United States will need to make some big, unilateral concessions

to assure China that it is not interested in military conflict.

For example, it could permanently withdraw several carrier battle groups from

the region, perhaps retiring one or two of them. Such actions would cause howls

of protest at home and among our allies in the region, and they would leave our

allies vulnerable for a period of time. Indeed, for these maneuvers to be

credible, Washington might have to stomach a fair amount of aggressive Chinese

bullying in the region; it should only reverse course if China seriously

threatens the political integrity of other countries. In other words, part of

this strategy involves an admission by America that China is the leading power

in the Asia-Pacific, and that other states in the region need to adapt to that

reality. Hopefully, after a few years, Beijing would begin to trust that Washington's

priorities have changed and to believe that it can devote more energy to

collaborating with America, and less to military preparations.

Another possibility is that other

Asian states would form a balancing coalition against China; this development

would not improve matters, since such a coalition could pose a major threat to

Chinese security. Perhaps an even worse eventuality would be if these states

aligned themselves with Beijing, instead of making the military investments

required for a credible balancing strategy. In light of these

possibilities, an integral part of the U.S. strategy would be getting its

allies to accept a fair amount of political indignity for a few years, in the

hope of creating a better regional order in the long term.

Risks and challenges abound, but

if I am correct that such concessions will be necessary to put the U.S.-China

relationship on a new, more cooperative footing, then much better to make them

now, while Washington has a major power advantage over Beijing, than in a

couple of decades, when the capability gap may have significantly narrowed.

In many ways, this strategy runs

counter to the liberal internationalist project, which is founded on the

global, stabilizing presence of America's armed forces. But if we want China to

be a full member of a liberal order, rather than an outsider like the Soviet

Union during the Cold War, we and our allies will have to risk a substantial

measure of security now in the hope of building a lasting and productive peace.

Sean Kelleher

is an attorney in Washington D.C. who has an M.A. in international politics. He

works on document review projects, blogs at

A Vegan View of World Politics

, and is writing a book on U.S. foreign policy.

February 26, 2014

Is it a great World War II website, or a great way to waste a month? Perhaps both

All 79 volumes of the official Army history of World War II are now available through one big fat link.

I could waste weeks on this site.

Yes, I confess: I

fear we focus too much on World War II in general. I once vowed to stop reading

about World War II and the Civil War until I knew more about other wars,

especially in other countries.

But how can you

resist this stuff? You can't go wrong reading the specialized volumes here for

valuable background on virtually any aspect of how a big military operates in

wartime. There is, for example, an entire volume on U.S. military operations in

the Middle East, and four times that many on military medicine in World War II.

How many books have you read about military medicine in combat conditions?

And the New York Times certainly could have used

this link the other day. And in an editorial today. Especially Chapter VI.

Bonus: Here is Adm.

Chester Nimitz's operational diary for World War II, now online.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers