Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 64

February 7, 2014

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: The Real Reason Why the Taliban Capture of a Military Dog is News

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

There has been a lot of response to the Taliban's recently

released video footage in which it touts the capture of what it originally

claimed was a U.S. military dog called Colonel. Thursday morning's initial

reports lacked much in-depth reporting and it turns

out the dog is thought to have been attached to British

forces and originally went missing in December after a NATO mission gone wrong.

The majority of headlines and discussion were focused not on the validity

of the reports or the video, but just the news that a war dog was captured.

Later commentary yesterday, like this Washington Post

blog post,

attempted to broaden the discussion by asking the question: "Why do we

care about this dog?" I take issue with this on a few levels, but on its

face this is not a totally worthless question to ponder. However, in this

instance it's the wrong question. It begs an answer that needs no

validation. You don't have to be a dog lover to understand that. You don't even

have to weigh the ethics of waging war or the cost of life -- whether soldier,

civilian, or canine -- to understand that. Yes, it pulls heartstrings to see

this dog, confused and uncomfortable. But the gut twist of this footage doesn't

begin and end with the emotion of seeing a dog in the hands of men who may very

well end his life. It's not just a hit to our collective morale.

The question we should be asking -- and forgive me, for I am

repeating

myself -- is this: Why does the Taliban care about this dog?

Why does the Taliban think that releasing a video of this

dog is going to make a difference to the U.S. military? For anyone who might

scoff or pass this off as a clumsy move on behalf of a few Taliban fighters who, by

showing off a handful of weapons and a dog, believed they scored a victory

against their enemy, seriously underestimates how seriously NATO forces need

and rely on these dogs. They also underestimate how good these dogs are at

their job, how many lives they save, and how much the men and women on the

ground value them -- consider them a fellow soldier more than a tool or piece

of equipment.

I hate to say it, but the Taliban got it right when they

banked they'd gotten their hands on something of unquantifiable value. And

that's a bit of news worth noting.

February 6, 2014

Future of War: Rosa Brooks smacks down 19th c. industrial era theories about warfare

The promised smackdown arrives.

Everyone knows that the character of war changes constantly but

that the nature of war is

immutable. Why do they know this? Because they were told so at war college.

Everyone, that is, except my FP

& Future of War teammate

Rosa von Brooks. She's read all the books and she

comes away unpersuaded. For example, she writes, "Take

cyberwar: Much of what is often spoken of under the 'cyberwar' rubric is not

violent in the Clausewitzian sense of the word. Cyberattacks might shut down the New York Stock Exchange and cause untold

financial damage, for instance, but would we say that this makes them violent?"

She notes that Clausewitzian strict

constructionists will then respond, "You can blather on all you

want about cyberwar or financial war, but if what you're talking about is not

both violent and political, it's just not 'war,' but something else."

Not so fast, she

counters. "But there are many other

ways to

understand and define violence. Consider various forms of psychological torture

or abuse. Or consider cyberattacks that lead to loss of life as an indirect

result of extended power outages: Why not view such attacks as a form of

violence if they lead predictably to loss of life?"

Then Brooks gets all neo-Westphalian on their

asses. "It is the state that creates and defines the role of the military....

It is also the state that defines the legal contours of war." So, for a truly

subordinate military, war might be war, but war is what your civilian superiors

say it is.

I can't do the piece justice with this summary,

so if you are gonna comment, please read the whole thing

first. Brooks, considered by some to be a leading candidate to become the next

president of Robot Rights

Watch, the cool new NGO, also provides links at the end to some of

her other writings.

Meanwhile, two other FPsters

have been dishing some good stuff lately.

Phil Carter, noting the Army's continuing campaign against

drinking too much alcohol, wondered why the Army is palling

around around Budweiser.

Stephen Walt compiled a list of the 10 biggest mistakes

of the Afghan war. This is the best such list I've ever seen. (Here's a weak dissent from

someone who doesn't seem to appreciate the difference between a genuine

coalition and a lot of caveated window-dressing.)

And in the Twitty world, I seem to have accumulated 1,000

followers. But a friend of mine tells me they might not all be real. If you are

not real, you probably should stop reading this blog.

Old soldiers don't die...

They're

colonels in the Army Reserves?

I

hear his lectures on World War I are great. "There we were, facing the Boche..."

The Future of War (no. 4): We need to protect our personnel from the moral fallout of drone and robotic warfare

By Lt. Col. Douglas Pryer, U.S. Army

Best Defense guest columnist

Until last year, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders required "actual or threatened death

or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others" for

a diagnosis of PTSD. How is it that drone operators can suffer PTSD without

experiencing physically traumatic events? The answer lies in the concept of

"moral injury."

Dr. Jonathan Shay

popularized the term "moral injury" in his book Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and

the Undoing of Character. To Shay, it is the moral component -- the

perceived violation of "what's right" -- that causes the most harmful and

enduring psychological effects from PTSD-inducing events. Dr. Tick, another

psychologist who has counseled hundreds of combat veterans, holds a similar

view. Tick contends that PTSD is best characterized not as an anxiety disorder,

but as an identity disorder stemming from violations of what you believe that

you yourself (or other people that you identify with) could or should have

done.

Other

mental health practitioners describe moral injury as something distinct from

PTSD, which they see as caused by physical reactions to physical stressors. But

moral injury, as Dr. Brett Litz and other leading experts in the field recently defined it, is "perpetrating, failing to

prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held

moral beliefs and expectations." Moral injury may follow a physical event, but

it can also follow events that are not physically traumatic at all.

Litz and his colleagues agree that, while PTSD and

moral injury share symptoms like "intrusions, avoidance, numbing," other

symptoms are unique to moral injury. These other symptoms include "shame,

guilt, demoralization, self-handicapping behaviors (e.g., self-sabotaging

relationships), and self-harm (e.g., parasuicidal behaviors)." They also

advocate different treatments for moral injury. While PTSD sufferers may be

helped via such physical remedies as drugs and the "Random Eye Movement"

treatment, those who suffer from moral injury require counseling-based

therapies.

There may be no stronger

case for the existence of moral injury than that presented by drone operators

who, far removed from any physical threats to themselves, suffer symptoms

associated with PTSD. Indeed, if moral injury is distinct from and not a

component of PTSD (as Dr. Brett Litz and his colleagues claim), it is

reasonable to conclude that drone operators are misdiagnosed as having PTSD: They

actually suffer from moral injury.

The

growing case for the existence of moral injury reinforces the idea that what

the military now calls the "human domain" of armed conflict is the most crucial

aspect of war -- even, paradoxically, of war waged via remote-controlled

machines. Lt. Col. (ret.) Pete Fromm, Lt. Col. Kevin Cutright, and I argued in

an essay that war is a moral contest started, shaped, and ultimately

settled by matters residing within the human heart. A group can be defeated in

every measurable way. It can have its immediate capacity to wage war destroyed.

However, if this group's members feel that it is right for them to continue to

fight, they will find the means to do so. There is often little difference

between believing that it is right to fight and possessing the will to fight,

we argued.

I

applied this idea to remote-controlled warfare in another essay, "The Rise of the Machines: Why

Increasingly 'Perfect' Weapons Help Perpetuate Our Wars and Endanger Our

Nation." Here, I argued that our nation needs to pay much closer

attention to the moral effects of our use of remote-controlled weapons. The Law

of Armed Conflict always lags behind the development of technology, I wrote,

and we should take little comfort in the fact that international treaty does not

yet clearly prohibit our use of armed robots for transnational strikes in

places like Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia.

There

is, for example, a profound perceptual problem related to one nation's warriors

remotely killing enemy warriors at no physical risk to themselves. You can

argue that this is a stupid perception with no historical basis in the Just War

Tradition, but the reason for the absence of this idea from this tradition is

clear: This technology is new. If you were to imagine robots attacking America

and the American military as unable to fight back against the humans

controlling these robots, it becomes easier to appreciate why many foreigners

(even many living in allied nations) consider transnational drone strikes to be

dishonorable, cowardly, or worse, inhuman acts.

I

concluded in this essay that armed robots should only be used in support of

human warriors on the ground, except in those cases when a strong argument can

be made to the world that a terrorist represents such a threat to the United

States that we have the right to execute this terrorist wherever he may be. The

alternative, I argued, is to ultimately create more enemies than we eliminate

with these weapons -- and to help set the conditions for forever war.

But our use of remote-controlled weapons must also account

for the long-term psychological effects of drone operators' perceptions of

right and wrong. International and local evaluations of wars or tactics as

illegitimate or unjust often derive from common human perceptions that U.S.

servicemembers can look within themselves to find. As Dr. Shay wrote in his conclusion to Odysseus

in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming, a book

about the inner struggle of ancient and modern warriors to recover from war:

"Simply, ethics and justice are preventive psychiatry." In the case of drone

operators, care must be taken to ensure operators can be convinced that it is

politically legitimate and morally just to kill their human targets and that

they do not intentionally or negligently kill non-combatants.

In closing, the idea that history is cyclical is an ancient

one. Hindus have long believed that this is the case. More recently, the Zager

and Evans 1968 hit song, "In the Year 2525," described civilization as

advancing technologically only to arrive at its starting point. This idea is

certainly proving true with regard to the psychological impact of war on those

who wage it. Soon, just as cavemen did long ago, America's remote-control

warriors will be able to look people in the eyes when they kill them.

Unless we turn America's servicemembers into psychopaths

devoid of conscience (a cure far worse than the ailments inoculated against),

we can be sure of one thing: The human cost to our side of this type of warfare

will never be as cheap as technocrats dream it will be.

Lt. Col.

Douglas Pryer is a U.S. Army intelligence officer who has won a number of

military writing awards and held command and staff positions in the United

States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

The views expressed in

this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or

position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S.

government.

February 5, 2014

The Future of War?: Expect to see urban, connected, irregular 'zombie' conflicts

By

David Kilcullen

Best

Defense future of war entrant

Thinking about future wars starts with

understanding current trends that are shaping conflict. Here are a few to

consider.

The first two are urbanization and population

growth. Since the industrial revolution, world population has shot up, from 750

million in 1750, to 3 billion in 1960, to 7 billion today. By mid-century there

will be 9.5 billion people on the planet, 75 percent of them in large cities.

Most will be coastal (80 percent of people already live within 50 miles of the

sea), with the fastest growth in the least developed parts of Africa, Asia, and

Latin America. The next 30 years could see 3 billion new urban-dwellers in the

developing world. The planet's most fragile cities may have to absorb the same

number of people that it took all of human history to generate, across the

entire globe, right up until 1960.

Edgar Pieterse, head of the Africa Center for

Cities, talks of "dramatic, disruptive change in only one generation" while the

urban theorist Mike Davis has written of an emerging "planet of slums" -- and

it's a fair bet that this will affect conflict, making wars even more coastal

and urban than they've always been, and further blurring the boundaries between

crime and warfare.

A newer, more disruptive trend is the explosion

in connectivity that has occurred in the same areas of the developing world

over the past decade. In 2000, for example, fewer than 10 percent of Iraqis had

cellphone reception, while Syria, Somalia, and Libya had no significant

cellphone systems at all -- Syria had just 30,000 cellphones for 16 million

people, while Libya had only 40,000. Ten years later, there were 10 million

cellphone subscribers in Iraq and 13 million in Syria, while Internet and

satellite TV access had massively expanded. Nigeria went from 30,000 cellphones

to 113 million in the same decade.

Connectivity has huge effects on conflict:

democratizing and weaponizing communications technology, and putting into the

hands of individuals a suite of lethal tools that used to belong only to

nation-states.

In August 2011, for example, in the Libyan

coastal city of Misrata, school children used mobile phones to mark Gaddafi

regime sniper positions on Google Earth, allowing French warships off the coast

to target them. In the same battle, rebels used smartphone compass apps and

online maps to adjust rocket fire in the city's streets. Syrian fighters use

iPads and Android phones to adjust mortar fire, and video game consoles and

flat-screen TVs to control homemade tanks. Snipers use iPhone apps and cellphone

cameras to calculate, then record, their shots.

The technology writer John Pollock has

brilliantly described the role of online activists in the Arab Spring, not only

for political mobilization, but also for logistics and tactical coordination --

as in April 2011 when Libyan rebels, at night in the open field, planned an

assault on a rocket launcher via a multinational Skype hookup. None of this

would have been possible a decade ago.

This democratized connectivity will

increasingly allow distant players to participate directly in conflicts. For

nation-states, we see this "remote warfare" trend in the Predator remotely

piloted aircraft, which can be flown from the other side of the planet through

satellite uplinks. But non-state groups can play the same game: In 2009, Iraqi

insurgents pointed ordinary satellite TV dishes at the sky, then used

Skygrabber, a $26 piece of Russian software, to intercept the Predator uplink.

The guerrillas had hacked the Predators's control system, far easier than

shooting down the actual aircraft.

There are constants in war, alongside these new

trends. Most wars are, and have always been, "irregular" -- conflicts where a

major combatant is a non-state armed group. Over the past 200 years, only about

20 percent of wars were state-on-state "conventional" conflicts -- the other 80

percent involved insurgents, militias, pirates, bandits, or guerrillas. Indeed,

interstate conventional war, though incredibly dangerous, is happening less and

less frequently, though irregular wars and intrastate conflicts remain common.

Irregular conflicts tend to be "zombie wars"

which keep coming back to life just as we think they're over. Iraq is a case in

point: By late 2009, through urban counterinsurgency, partnership with

communities, and intensive reconciliation efforts, U.S. forces had severely

damaged al Qaeda and brought civilian deaths to the lowest level in years: Only

89 civilians were killed across all of Iraq in December 2009, down from over 1,000

per month in mid-2008, and a shocking 3,000 per week in late 2006. But rapid

and complete U.S. withdrawal in 2010 -- combined with sectarian politics and

the reinvigoration of al Qaeda through the Syrian war -- pulled the rug from

under local communities, reviving a conflict that a succession of U.S. leaders,

on both sides of politics, have been incorrectly claiming was over ever since

May of 2003. Likewise, in places like Afghanistan, Colombia, Somalia, Congo,

the Central African Republic, Mali, and Sudan, current outbreaks are not new --

rather, they're revivals of generations-old conflicts that keep coming back.

Colombia's FARC rebel movement, for example, turns 60 in 2014.

A final constant worth mentioning is what we

might call "conflict entrepreneurs" -- fighters who aren't so much trying to

win a war, but prolonging it to generate wealth or authority in fragmented

societies. Somali clans, Afghanistan's Haqqani network, and gangs like Kenya's

Mungiki or Mexico's Zetas fall into this category: They fight not for victory,

but to keep conflicts going for their own benefit. Turning conflict

entrepreneurs into stakeholders in stability is a huge and daunting task.

What does all this suggest about future war?

Well, as America and its allies pass -- thankfully -- away from an era of

large-scale intervention in overseas counterinsurgencies, it's tempting to

think that each year's crop of new irregular wars is just so much background

noise that we can afford to ignore. Unfortunately, that's not true anymore, if

it ever was: In an increasingly urbanized, massively connected world, where

empowered individuals and non-state groups will access communications and

weapons technology that used to be the preserve of nation-states and future

conflicts will leap international boundaries, we ignore these conflicts at our

peril.

One crystal clear lesson for future war emerges

from the last decade. This is that unilateral intervention in other people's

wars is not the way to go -- and neither is large-scale counterinsurgency

which, though doable, is extraordinarily difficult, and far from desirable in

humanitarian, financial, or political terms. Interventions, particularly

counterinsurgencies, must be an absolute last resort. But ignoring future

conflicts doesn't work either -- urban, zombie, irregular crime-wars, that leap

national boundaries and feature non-state groups with technology and

connectivity only states used to have, will spread rapidly, sucking in

surrounding regions, as Syria is doing now, and as Afghanistan did before 9/11.

Dr.

David Kilcullen

is a former Australian soldier,

diplomat, and policy advisor for the United States and other governments. He is

the founder and non-executive chairman of

Caerus

Associates

,

a research and design consultancy, and the author, most recently, of

Out

of the Mountains

.

The Future of War essays: The attack of the robot rats in the Korean War of 2019

By Col. Gary Anderson, USMC (Ret.)

Best Defense future of war department, red team director

The bomb that killed the president of

the United States on May 31, 2019, was small but powerful. So was the

one that killed two members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and blew the legs of

their chairman during their weekly meeting at the Pentagon. The question of how

someone could penetrate the security of the two most secure buildings in

Washington might have triggered conspiracy theories for decades to come if

events halfway around the world in Korea, where similar explosions disabled key

American and South Korean military command posts, had not provided an ominous

answer. Simultaneously, much of Seoul was leveled by a devastating massive

artillery and rocket barrage. All this was the first stage of the Second Korean

War.

The North Korean force that crossed the

Demilitarized Zone, and overran most of South Korea within two weeks has been

described as a "horde." In reality, it was smaller than the U.S. and South

Korean force that opposed it. To be sure, the vast number of armed North

Koreans who followed the assault force was larger than the allied force, but it

was primarily tasked with population control, exterminating South Korean

political and intellectual leadership, and providing security against stay-behind

resistance fighters as well as American and South Korean Special Forces. In

reality, what caused the havoc in Washington and Korea was a revolution in

military affairs that Western planners had overlooked.

While the United States concentrated on

large robotic unmanned aerial systems to gather intelligence and deliver

precision weaponry, the North Koreans were going small with ground robotics.

The devices that infiltrated the Pentagon and the White House were about the

size of a small cell phone and were camouflaged to look like rodents. Indeed,

one alert White House aide spotted one of the devices, but instead of sounding

the alarm, she called for a General Services exterminator. The North Koreans

had also developed highly lethal enhanced explosives as payloads to be carried

aboard the tiny robotic assassins.

Half a world away, the counterparts of

the Washington assassins were similarly small. Instead of carrying explosives

they carried miniature cameras and transmitters that allowed them to send

pictures and even sound from their target locations. There were hundreds of

these devices. They had been planted by sleeper agents, and were located at

every key road intersection, bridge, cloverleaf, and airfield. The devices were

transmitting by satellite relay to the commanders of the North Korean assault

columns. Every time an allied unit tried to maneuver through one of these key

points or launch aircraft from airfields, they were instantly targeted by enemy

artillery. Except for the robots equipped for sabotage and assassination, which

were fairly complex to allow infiltration, these forward observer robots were

relatively simple. Once hidden in their overwatch locations, they were just

mobile enough and smart enough to move to more secure locations if they

perceived proximate danger. They too were roughly disguised as rodents, and so the

Americans began to call them "rats."

In addition, the North Korean tactical

commanders knew where the Americans and South Koreans were not located, which enabled them to find gaps and maneuver around and

behind the allies. When the U.N. forces tried to counter these maneuvers, they

found themselves pinned down by deadly indirect fire. Within 14 days, the

allies found themselves holding on to an enclave around the port of Pusan. The

situation did not begin to stabilize until the allies began using dogs,

detector devices, and even children to find and eliminate the tiny robotic

spies. Once again, the adaptability and resourcefulness of American soldiers

and Marines compensated for the lack of foresight of their leaders. But a long

slog lay ahead if the South was to be re-liberated.

As with the Germans in the Second World

War, the North Korean blitzkrieg was not a revolution in military affairs with

wonder weapons. The northerners had used existing technology in a combined arms

approach that created strategic surprise among their opponents who had counted

on technology and an all seeing overhead operational picture. Instead, it was

the North Koreans, moving through a cloud of instantaneous real-time intelligence,

who achieved information dominance.

Ironically, the Americans had

experimented with this concept in the latter years of the 20th century,

but it was abandoned after 9/11. There was much more money in large automated

airborne systems. The world saw that the Americans spent billions, but were beaten

by a foe that invested millions.

Gary Anderson is a retired Marine Corps colonel. He teaches red teaming

at the George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs.

The Future of War essays: It's back to the beginning, or, 'The nearness of you'

By Lt. Col. Douglas

A. Pryer, U.S. Army

Best Defense guest

columnist

Technology is quickly reversing a psychological trend that

has existed since cavemen first threw rocks at each other many tens of

thousands of years ago.

The French strategist Ardant du

Picq wrote: "To fight from a distance is instinctive in man. From the

first day he has worked to this end, and he continues to do so." Distance

not only provides warriors with a sense of safety, but it reduces their

psychological resistance to killing other human beings.

However,

today, while many of America's drone operators sit physically safe in trailers

in Nevada, their human targets on the other side of the planet appear no

further away than if these operators were watching them through the sights of

an M16 rifle. Although the physical distance between warrior and target has

reached its physical limit (on this planet anyway), the subjective distance

between the two is rapidly closing. This trend will continue for the

foreseeable future, as sensors rapidly improve in response to the need to limit

noncombatant casualties -- a need that is a condition of military success for a

mature democracy like the United States in a world increasingly "flattened" by

another growth industry, information technology.

It is not

hard to imagine someday drones that are the size of a bullet, that transmit

both color video and audio feeds, and that hover just feet away from human

targets before entering their bodies. When this happens, there may be little to

subjectively distinguish the combat experience of a drone operator and that,

say, of a G.I. during World War II who stuck his bayonet in the guts of an

enemy soldier.

In his 1995 book, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of

Learning to Kill in War and Society, psychologist

and former infantry officer David Grossman postulated that the physically closer a warrior

is to the person they are killing, the greater their natural resistance to

killing, and thus the greater their risk of psychological injury should they

kill. In a graph, Grossman depicted warriors' resistance to killing increasing

the closer they come to their human targets. The least resistance is felt

within those warriors who kill at maximum range (bombers and artillery). Inner

resistance steadily increases from there to those who kill with long-range

weapons (sniper, missiles), then mid-range weapons (rifles), then hand-grenades,

then close-range weapons (pistols), and, finally, those who kill in

hand-to-hand combat.

Grossman's

hypothesis is but a general rule. The small percentage of warriors who are

psychopaths are obvious exceptions to this rule. Different levels of resilience

among individuals account for other exceptions.

To illustrate the latter, in his

2005 book, War

and Soul: Healing Our Nation's Veterans from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, the psychologist Dr. Edward

Tick gave the examples of a World War II bomber pilot and a nuclear weapons aircraft

inspector, who both suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The pilot told Tick that he had refused to open his aircraft's bay doors and drop bombs

on a German city. With his crew chief screaming at him, he finally did it.

Afterwards, he was haunted by his belief that he was a "mass murderer." The

inspector had examined nuclear bombs onboard B-52s, a "maximum range" weapon.

He had not killed anyone, but he could not shake the judgment that he had

conspired "to threaten the world."

Such

anecdotes can be contrasted with stories of warriors who killed in

close-quarters combat without incurring psychological injury. Nonetheless,

despite many exceptions, the weight of evidence strongly supports the general

validity of Grossman's theory.

During

the current global conflict that, for one side anyway, is increasingly

remote-controlled, a revision of Grossman's hypothesis is in order: It is not

the actual physical distance, but rather the subjective distance between normal

human beings that determines their inner resistance to killing each other.

This

suggested revision does not mean that a drone operator and an infantryman

experience the exact same thing when they kill a human target of similar shape,

size, and resolution. The drone operator's adrenaline levels are unlikely to be

as high, since he is not himself in any physical danger. His senses are not as

immersed in the graphic sights and sounds of battle. And he just does not

"feel" as close to the enemy through his other senses. His experience is

diluted. He is, in effect, sipping reality through a straw. Thus, "subjective"

distance is related to, but not entirely the same thing as, "apparent" or

"visible" distance.

Most

people would agree that reality as we experience it is fundamentally

subjective, making this revision both obvious and intuitively true. The scanty

evidence published thus far on the negative mental outcomes associated with

drone operations very roughly corroborates this revision, too.

There

are, for example, numerous anecdotal accounts of drone operators suffering from

such negative psychological outcomes as PTSD and depression despite their

physical distance from the battlefield. Brandon Bryant, for example, worked as

a drone operator at a Nevada Air Force base. When he left his squadron, he was

presented a certificate in which his squadron claimed 1,626 kills over a period

of several years. Bryant has since been diagnosed with PTSD. In an interview,

he described seeing three men hit with a missile and being able to see one guy

running forward, bleeding out, while missing his right leg. "People say that

drone strikes are like mortar attacks," he said. "Well, artillery doesn't see

this. Artillery doesn't see the results of their actions. It's really more

intimate for us, because we see everything."

A staff sergeant

supervising support to drone crews and mission planners was one of the many

military servicemembers Peter Singer interviewed for Wired for War: The

Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century. "What angers me is that as a service," she said, "we are not doing a

good job on PTSD [among drone pilots and operators]. People are watching

horrible scenes. It's affecting people. Yet we have no systematic process on

how we take care of our people."

The

U.S. Air Force has released some quantitative data on these negative

psychological outcomes. For example, the service reported in December 2011 that, of 900

drone pilots and operators surveyed, 4 percent were at high risk of developing

PTSD. It also stated that 25 percent of Global Hawk operators and 17 percent of Predator and

Reaper pilots suffer from clinical distress, which is "defined as anxiety,

depression, or stress severe enough to affect an operator's job performance or

family life." It also reported that 65-70 percent of those with signs of mental

illness are not seeking treatment for their condition.

However,

compare the low percentage of drone operators at high risk of PTSD to the 12-17 percent of soldiers and Marines returning from Iraq and

Afghanistan who, based on their responses to post-deployment questionnaires,

fell into the same high-risk group. There is clearly a qualitative

psychological difference between the experiences of drone operators and ground

troops (such as the latter's greater subjective closeness to their targets and

their experiencing other potential sources of trauma like roadside bombs and

being shot at).

Consider

also the study that the U.S. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center published

earlier this year titled, "Mental health diagnoses and counseling

among pilots of remotely piloted aircraft in the United States Air Force."

This

study reported that, between October 2003 and December 2011, USAF personnel

operating drones in Afghanistan and Iraq suffered negative mental outcomes at

rates comparable to pilots of manned aircraft in these two countries -- pilots

who predominantly flew missions like close-air support, casualty evacuation,

and reconnaissance missions.

You

would expect, according to Grossman's theorem, that the pilots of manned

aircraft suffer adverse psychological outcomes as a group less than ground

troops due to their greater physical distance from the enemy. And, according to

my revision, you would expect manned-aircraft pilots to suffer worse outcomes

than drone operators due to their increased subjective proximity to the

battlefield.

A

drone mission, though, lasts much longer than a manned-aircraft mission, and

drone operators more routinely inflict death, either via missiles or by cueing

the actions of ground troops. They also more frequently observe potentially

troubling events. For every potential source of trauma that a manned-aircraft

pilot experiences, a drone operator probably experiences two or three such

events. Thus, in this case, quantity counterbalances quality (the subjective

intensity of the experience).

I

know this analysis is less than foolproof. Yes, it is self-evident that ground

troops are, as a rule, physically and subjectively closer to human targets than

manned aircraft pilots who, in turn, are subjectively closer to their targets

than drone operators. However, what percentage of the servicemembers in the

above surveys actually killed someone? Of these, what percentage suffered which

negative psychological consequences at what distances from the person they

killed?

These

data just have not yet been published. As data slowly comes to light, though,

I'm confident that it will show that this proposed revision -- like Grossman's

original theory -- holds generally true.

Lt. Col.

Douglas Pryer is a U.S. Army intelligence officer who has won a number of

military writing awards and held command and staff positions in the United

States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The views expressed in

this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or

position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S.

government.

February 4, 2014

Can cutting drone money be a good idea? And is the Navy taking the lead in drones?

Cutting drone spending doesn't strike me as wise. It does strike me

as being additional evidence of the Pentagon's being locked in the present

("readiness") instead of thinking about tomorrow ("preparedness").

The only possible

argument I could see is that we have invested enough in current generation

technologies, and should hold back on acquiring more while the field develops.

That would be more plausible if acquisition of the old manned systems also were

being stopped.

As I understand it,

drone R&D will start to decline while acquisition increases. One can only

hope that means snazzy new super-fast long-range stealthy

drones are being purchased,

as well as other innovative types. As an article by Matthew Hipple in the February issue of Proceedings puts it, "Short-term drone development

should concentrate on areas where autonomy is easiest and expendable platforms

are most useful, giving drones a space for more successful and immediate

growth."

In another article

in the same issue, retired Navy Capt. Edward Lundquist makes a good argument

that the next big surge in jointness should be in ensuring that our drones in

the air, on land, and under water can communicate with each other. He quotes

Eric Pouliquen of the "future solutions" branch at NATO's transformation office

in Norfolk, Virginia as saying that, "It would not make sense that we develop a

set of standards for something that swims that is completely different from a

vehicle that is on land, for example."

I get the sense that

the regular Navy is getting back into the game, after a couple of decades of taking a back

seat to the Army, Marine Corps, and Special Operators.

(One qualm: Why

isn't NATO's transformation office in Silicon Valley? I mean, my Quaker

ancestors landed not far from Norfolk, but they had the sense to head West, and southeast Virginia today is

one of the most backward-looking parts of the country, and indeed is thousands

of miles from the nation's major technology centers.)

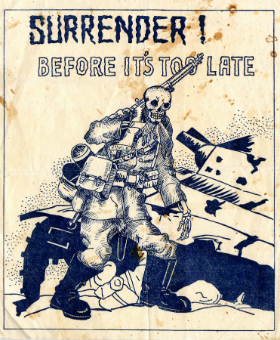

Tom surrenders, starts Twitting

A lunch talk the other day with a couple

of friends (@jackshafer and @timothynoah1) persuaded me that I should

drop my ban on social network junk and dive into the Twitter pool. Not quite

sure how they did that. I came away thinking I was being a snob for refusing to Twit. Or maybe I just ate a bad chili pepper.

So I am now @tomricks1.

I fear I may have just jumped on a tiger. Before I finished filling out the damn profile on Friday I

had 100 followers. The following morning I got suspended by Twitter, not sure

what I did. Now back up and running.

Leaked Taliban inspector general report: We may have too many literate fighters

The

Taliban's inspector general has compiled a scathing report that charges the

organization's leaders with recruiting too many men who can read and write,

Pashtun insiders familiar with the document said yesterday.

The

internal study notes that the Taliban's greatest gains have come when its

members are uneducated, and questions as "fundamentally unsound" the recent

decision to permit university graduates to join the organization, albeit on

double secret probation. "Who knows what thoughts may have been put in their

heads?" asked the Taliban official, Gulam Nabi, who is Afghan but who like many

Americans goes by two names.

The

report, which was provided to the Best Defense by a usually reliable source in

an unreliable mud hut near Lashkar Gah, also discerned weak oversight and

accountability in preventing educated men from joining. Yet it also questioned

the goal of Taliban chief Mullah Omar to achieve 100 percent illiteracy within

three years, saying that target may be "unrealistic and unattainable."

Addressing the issue of whether forces unable to keep written records could

keep reliable track of their weapons inventory, the Taliban IG noted that there

is not one instance over the last 2,500 years of an illiterate Afghan ever

losing track of his weapon: "His women? Perhaps. His sheep? It happens. His

sword or rifle? No. Not gonna happen."

The

report concludes by warning that if current trends in literacy continue, parts

of its fighting force could become as ineffective as Afghan National Security Forces.

In a

related story, al Qaeda yanked the accreditation of its Syrian affiliate, stating

that the branch had fallen out of compliance with several key tenets of

membership. Some of the violations were purely technical, such as killing rival

leaders without first informing its higher headquarters.

Author's note: Yes, this post is

my salute to

DuffelBlog

.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers