Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 68

January 20, 2014

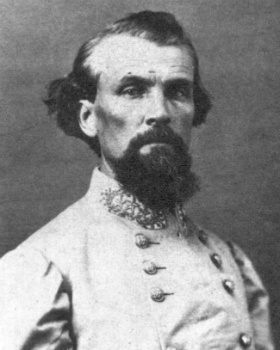

It's high time to dump the Confederate names tarring the honor of our Army

By "Soldiers Diary"

Best Defense guest columnist

It's 2014 and we still have Army bases named in honor of generals who

fought for the Confederacy. It's

ridiculous, absurd, and time that these bases be renamed.

Jamie Malanowski last year wrote a fantastic op-ed for the New York Times titled "Misplaced

Honor." He detailed the numerous Army bases, mostly in the South, that are named after generals

who fought for the South and were responsible for the deaths of tens of

thousands of Americans. These bases

include Fort Lee, Fort Hood, and Fort Bragg, to name but a few.

As we observe Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the U.S. Army should take a

hard look at the names of Army installations across the United States and

rename those installations.

It would be fitting to change Fort Bragg to Fort Gavin, the first

commander of the 82nd Airborne Division and World War II hero. Fort Hood could be renamed Fort Patton, Fort

Rucker could be renamed Fort Marshall, and you could even rename Fort Lee, Fort

Calrissian. It sounds ridiculous at

first, but not after taking into consideration the fact that Lando is not

responsible for more American soldiers' deaths than were Nazi Germany and

Imperial Japan combined. Nor did he lead a force in order to preserve a slavery-based

economy.

We can still honor the soldiers who fought for the South, and monuments

on the battlefields like Gettysburg are still appropriate. However, in 2014, having bases named after

the leadership of the Confederacy is just a bit outdated. I do not speak for African-American soldiers,

but I wonder if anyone has ever asked them if they feel it is appropriate.

This is not all the Army and the other services should do to advance in

to the 21st century. Other forms of

absurdity continue that the military should take a stand against. A start would be to end support such as

providing a color guard for professional football games that involve the team

from Washington D.C. Call a spade a

spade, recognize that the term "Redskin" is a derogatory

term, and end support for that football team until Dan "Chainsaw" Snyder also realizes

it is 2014.

"Soldiers Diary"

is an active-duty Army officer. This article represents his own views, which do

not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Defense Department, or Dan

Snyder .

The Future of War (IV): What should replace the current authorization of force?

By the Future

of War

team, New America Foundation

Best Defense office of the future

A pivot point for serious consideration of some of the issues

discussed so far in this series was provided by President Obama's speech at the National Defense

University in Washington in May, which was designed to lay the political

groundwork to wind down America's longest war: the war that began on 9/11. The

most significant aspect of the speech was the president's case that the

"perpetual wartime footing" and "boundless war on terror"

that has permeated so much of American life since 9/11 should come to an end.

Obama argued that the time has come to redefine the kind of conflict in which

the United States is engaged, saying, "We must define the nature and scope

of this struggle, or else it will define us." This is why the president

focused his speech on a discussion of the 2001 Authorization for the Use of

Military Force (AUMF)

that Congress passed days after 9/11 and that gave George W. Bush the authority

to go to war in Afghanistan against al Qaeda and its Taliban allies.

Few,

if any, in Congress who initially voted for the AUMF understood at the time that

they were voting for a virtual blank check that has provided the legal basis

for more than a decade of war. It is a war that has expanded in recent years to

other countries in the Middle East and Africa, such as Yemen and Somalia.

Some

argue that when U.S. combat troops finally withdraw from Afghanistan in

December 2014, the nation will no longer be at war, and the 2001AUMF should be

repealed -- or be deemed to have effectively expired. Others argue that the end

of the conflict in Afghanistan will not mark the end of U.S. efforts to use

military force against terrorists in other parts of the globe, and that we need

some sort of new AUMF to structure (and constrain) such future uses of force.

But what, if anything, should the United States replace the 2001

AUMF with? There are a host of

nitty-gritty policy questions we can help address:

Both of the Special Operations raids against al Qaeda members

and allies in Libya and Somalia in early October were conducted under the AUMF.

How does one get congressional buy-in for a new legal framework that might

constrain such raids?

What should the United States do about the 40 or so prisoners at

Guantanamo Bay who are deemed "too dangerous to release," but are not

chargeable with a crime, and who would theoretically have to be released if the

present AUMF expired?

And how exactly would the end of the present AUMF affect the CIA

drone program, which is somewhat dependent on those authorities?

Although a number of scholars and think tanks are looking at what

should come after the AUMF, much of this work is being done in a conceptual

vacuum. While the "Future of War" project will engage on the AUMF and related

immediate policy questions, our recommendations on these issues will be

grounded in our broader study of how warfare and the state are changing.

The Future of

War project is led by Peter Bergen, director of national security

studies at the New America Foundation, and the author of several books. This series was drafted by him and the

team's other members: Rosa Brooks, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Sascha Meinrath,

and Tom Ricks.

The Gates files (IV): Boy, does he hate attending those international conferences

Gates on the annual Munich Security Conference: "incredibly

tedious."

Gates on NATO meetings: "excruciatingly boring."

The Conference of Defense Ministers of

the Americas: "boring beyond words, and little ever results."

(And even more to come)

January 17, 2014

Hey Tom, I'm finding this blog a bit boring lately, with too many similar points of view on the same damn subjects

By "

A Reader Becoming Less Faithful"

Best Defense guest

columnist

Why? It is the same topics each

time. My point about challenging the paradigm is that it would not be just

challenging the left/right paradigms, it should challenge both.

For instance, we talk of

leadership in the ranks, but would it be out of line to have someone actually

come out and document the correlation between the GOs who talk a big game once

in retirement, but refused to speak up while on AD?

On the topic of suicide,

why are we not questioning how so many people with so many pre-enlistment

issues actually get in the military and why the go there in the first place?

(Over 50 percent of all military suicides are by folks who never deployed to

anywhere.)

On retirement, there

have been some interesting takes, but none that factor in the collateral

problems that go with a military career into that "benefits" package.

On the UCMJ, I have

never seen an article from anyone (right or left) explaining why it is so

important in certain areas, yet I have seen articles bemoan the suicides of

folks who were harassed due to falling asleep on watch in a combat zone.

On the female topics,

no one and I mean no one has addressed how much women have been accommodated in

terms of quotas, standards, set asides, frat, pregnancy, etc...

On Gitmo? Has anyone

explained the Geneva Conventions and written on why, how, and where they are

needed and how they could and should apply to the POWs? No, we only get stories

that Gitmo is wrong, that they should be charged as criminals, etc...even in

the right-wing pages you mostly only see them calling for blood, no mention of

how the Geneva should be applied and why then it would be wrong to let those

folks go.

I guess what I am saying

is that with the talent pool you have available, the blog has the ability to be

a lightning rod that questions the CW and should be able to bring realistic

questions and answers, but at times be honest that there may not be one.

Heck Tom, your pet peeve

on procurement and O&M, there has to be someone who can attack it in a

manner to make folks understand that just cutting it is not the answer and that

massive reform is needed, but usually all the authors do is say "cut the

budget" thinking that the military will react like a private business, but

it can't since it is not a private business. I bet if people knew that 800k of

the folks in the O&M budget are civilians they would gasp! Sorry for the

rant, the blog is awesome, you have been seriously kind enough to even engage

us and I really do think you are one of the few journalists who actually gives

a shit.

I think I am just

searching for a blog that is not afraid to step on those third rails, but do so

in a way that forces others to look as well.

"A.R.B.L. Faithful" is

an active-duty servicemember.

The Future of War (III): Some questions for consideration in light of the changes

By the Future

of War

team, New America Foundation

Best Defense office of the future

Law,

institutions, and political organizations always lag behind changing

technologies. While no one can predict with any certainty precisely how evolving

technologies will change the future shape of law and political structures, New

America's "Future of War" project will map out the key conceptual and legal

questions that we need to grapple with as we move forward.

Changing technologies are

simultaneously increasing and decreasing state power; how will these

countervailing trends change the nature of state power vis à vis other states

and non-state actors?

Will

they drive changes in how states interact with one another? On the one hand,

wealthy and powerful states -- in particular, the United States -- now have

unprecedented means of exercising power. Massive surveillance power,

space-based weapons systems, and so on remain within the sole province of

powerful states. Even drones are primarily tools of powerful states, since only

those states have the anti-aircraft capabilities to prevent incursions by

"foreign" drones and the broad-based intelligence capabilities that permit

drones to target specific individuals. On the other hand, individuals and

non-state organizations can confound state power in new ways, both through the

use of sophisticated cyber tools and through the dispersed and decentralized

use of simple, low-tech weapons such as IEDs, which are difficult to track and

control.

As technologies of

violence and control change, so do the concepts of "war" and "peace." Does

"armed conflict" versus "unarmed conflict" still make sense as a distinguishing

category? Should we seek to develop rules governing the "state use of force

across national borders"?

If we retain existing

constructs of war and peace, how do we define these? In the "war" against al Qaeda

and its allies, "the battlefield" is potentially anywhere on the globe and "the

enemy" is not another army but a loosely associated group of individuals of

varying nationalities. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were armed conflicts,

but as a legal matter, is the United States in an "armed conflict" with

suspected violent extremists living in Bosnia, or with militant leaders in

Pakistan's tribal regions? Are we in an armed conflict with suspected al Qaeda

"associates" in Somalia? Is a U.S. drone strike in

Somalia a lawful strike against an enemy combatant in an armed conflict, or the

illegal, immoral murder of a human being in a foreign country (and a possible

violation of sovereignty and the United Nations Charter to boot)?

How do we decide who is a

combatant in this new kind of armed conflict, which is not fought by uniformed armies? How do we

define "direct participation in hostilities" when any "hostilities" might be

months or even many years in the future, and might involve anything from the

destruction of a privately owned power plant to an internet denial-of-service

attack? If we're truly in a "war," it's surely

reasonable to consider an al Qaeda operative with bombs strapped to his chest a

combatant who can be targeted or killed. But what about an al Qaeda financial

supporter, or a propagandist who sets up web sites urging violent jihad? Are

the drivers, bodyguards, servants, and wives of al Qaeda leaders combatants?

Would a Somali tribal militant whose operations are wholly confined to Somalia

be considered a combatant if he belongs to an organization that is loosely

affiliated with al Qaeda?

How do we protect

human rights and human dignity in this murky world? If we can't figure out

whether or not there's a war -- or where the war is located, or who's a

combatant in that war and who's a civilian -- we have no way of deciding

whether, where, or to whom the law of war applies. But if we can't figure out

what law applies, we lose any principled basis for making the most vital

decisions a democracy can make, such as: When can lethal force be used inside

the borders of a foreign country? Who can be imprisoned, for how long, and with

what degree, if any, of due process? What matters can the courts decide and

what matters should be beyond the scope of judicial review? When is government

action and administrative procedure guarded by national security interests and

when must government decisions and their basis be submitted to public scrutiny?

And ultimately: Who lives, and who dies?

How does the migration of war

into the cyber domain complicate these questions? Just as the law lags far behind

advances in drone technology, so too the law has

little to say about cyberwar, particularly in determining when and if a cyberattack

is an "act of war." (Similarly, despite the increasing militarization of

space, space law is only in its infancy.) There has

been some discussion about these issues at the Pentagon, but very little in the

public space. But it's important to consider, for instance, whether a

large-scale Stuxnet-like attack on U.S. infrastructure would be an act of war

or not. Would it depend on whether the attack was unleashed by a state, an

organization, or an individual? How would one define "combatants" and civilians

in a cyberconflict?

What does civilian control of

the military mean in the context of these rapidly changing technologies? Consider cyber: There are

reports of a confrontation three years ago between the Obama White House and

the Pentagon over the issue of the pre-authorization of responses to a cyberattack.

The Pentagon argument was that it simply couldn't wait for the White House to

review the situation and decide to act. The White House ultimately responded

that the Pentagon would have to wait for the president to get involved, just as

it does with nuclear weapons. This exchange illustrates some of the new

questions being raised as warfare evolves that are not being answered in a sufficiently

coherent way.

How can we prevent

interstate conflict in a world in which norms of state sovereignty are changing

and eroding? Both human rights norms and security concerns have challenged

traditional understandings of state sovereignty, which is increasingly viewed

as a privilege earned by states that "follow the rules" and potentially waived

by those that do not. In many ways, the shift away from absolutist conceptions

of state sovereignty has been a positive development from a human rights perspective.

But with the U.N. Security Council politicized and often paralyzed, powerful

states -- such as the United States -- have increasingly taken it upon

themselves to determine when it is appropriate to use force inside the borders

of another state, a practice that jeopardizes the already fragile post World

War II collective security bargain.

In

addition to grappling with such large-scale conceptual questions, New America's

"Future of War" project will engage with current policy debates that relate to

these broader questions.

The Future of

War project is led by Peter Bergen, director of national security

studies at the New America Foundation, and the author of several books. This series was drafted by him and the

team's other members: Rosa Brooks, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Sascha Meinrath,

and Tom Ricks.

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: A Fitting Farewell for Kaiser, Plymouth, MA Police Dog

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief

Canine Correspondent

On May 29, 2013, one

of the handlers in the Plymouth Police Working Dog

Foundation posted news that his canine partner, Kaiser, a two-and-a-half year old

German Shepherd had been diagnosed with kidney disease. Kaiser had "battled this disease

with vigor and toughness," the likes of which his handler Plymouth Police patrolman Jamie

Lebretton had never seen before. But alas "the disease has taken the upper hand

forcing him out of his craft and ultimately out of this world." It was a gut-wrenching choice for Lebretton, but he decided that his

dog was suffering undeservedly and two days later they would be putting Kaiser

to sleep.

The notices (and the story) that then unfolded on the stream

of this Facebook page were as personally raw as they were moving to read, even

though this happened more than six months ago.

On May 31, 2013:

K9 Kaiser

End of Watch

5/31/13

1213 hrs

Then sometime later that day, Lebretton posted this message:

"RIP my boy. I could not have asked

for a better partner or friend. May you rest easy and wait for me at that

sacred bridge. I will be there my friend. I will be there. I will never forget

you or our accomplishments. You made me a better person, a better handler, and

a better cop. Till we meet again kai. I love you and will miss you daily.

...And to my boys and blue. Never in my career have i

ever been so proud. You out did yourselves today. I could not have asked for a

better send off. Kaiser truly was part of

the department and loved being a police dog. My fellow K-9 handlers, you are a

cut above and showed everyone what being a handler is all about...our pups. I

thank each of you and you have my respect forever.

...Lastly, to all of you who sent

your regards over the past few days...I thank you. I read every single post and

listened to every message. Kaiser served you well and the streets of Plymouth

were safer when he was on patrol. The compassion was overwhelming and i am

humbled at the support from perfect strangers."

Lebretton's humble thanks perhaps bely the true range the

impact Kaiser's parting had made. By June 1, 2013, the department posted that

they had received condolences from: "the great people

of Plymouth, MA ... throughout the USA and even Ireland, Afghanistan, Brazil,

Norway, UK, Canada, Russia, Bosnia, and even the outreaches of Australia." Animal

Planet Romania even posted a message about Kaiser on their Facebook page.

More stirring than these posts

was the photo (the lede image here) of the final sendoff this police department

gave Kaiser as he and Lebretton took their final steps together. We

"like" these posts; we share these stories because they're touching and because

we care about these men, their dogs, and their service. But this photo shows us

in one single moment (or frame) what these dogs mean to their fellow officers.

I don't consider it a stretch to include police dogs in our war-dog

posts. They may not be in a "combat zone" or part of a branch in the U.S.

military, but the working dog community is an inclusive one -- it's not overstating

the kinship to say that they're all part of the same family.

RIP Kaiser.

January 16, 2014

The Gates files (III): Fights with the Air Force, DOD personnel officials, the VFW

Gates came to believe that

extending the tours of soldiers in Iraq carried a huge cost. "I believe those

long tours significantly aggravated post-traumatic stress and contributed to a

growing number of suicides." (This made me wonder if there has been a study

looking to see if there is a correlation between Army suicides and the duration of tours. I asked around with

some smart guys and couldn't find any.)

One reason he

cancelled parts of the ballistic missile defense program: They "simply couldn't

pass the giggle test."

PowerPoint was

"the bane of my existence

in Pentagon meetings." But he didn't ban them, as other senior officials have

done. (And they also said, send me the slides ahead of time and I will read

them -- but I won't sit in the dark while you read them to me.)

Why he was

skeptical of the Air Force's bid to control drone capacity: "The Air Force was

grasping for absolute control of a capability for which it had little

enthusiasm in the first place."

He came to loathe

the office of the Pentagon's undersecretary for personnel and readiness.

"Virtually every issue I wanted to tackle ... encountered active opposition,

passive resistance or just plain bureaucratic obduracy from P&R."

The VFW and the

American Legion were major pains. "The organization were focused on doing

everything possible to advantage veterans, so much so that those still on

active duty seemed to be of secondary importance."

The problem with

generals: "In war, boldness, adaptability, creativity, sometimes ignoring the

rules, risk taking, and ruthlessness are essential for success. These are not

characteristics that will get an officer very far in peacetime."

(And still more to

come...)

Rangers are NOT leading the way

By Col. Ellen Haring, U.S. Army

Reserve

Best Defense guest columnist

January 24, 2014 marks the one-year anniversary of the

elimination of the military's official policy that kept women from accessing

nearly a quarter of a million military jobs. So, what has changed for military

women in the past year? Not a lot. The military services and Special Operations

Command were given three years to open up all positions or to request, by

exception, to keep some positions closed. So far, no requests have been made to

keep any positions closed, but few positions have actually been opened.

On July 2, 2013, a 7th Infantry Division (ID) operations

order encouraged soldiers to apply for the Army's Ranger School. According to

the order that went to all soldiers in a subordinate intelligence brigade at

Joint Base Lewis-McCord, the unit is looking to "increase Soldier leadership

skills across the Brigade". There is one catch to this leadership opportunity. Women

still need not apply.

According to the Army's Ranger training brigade website,

Rangers are soldiers who are highly trained in the principles of leadership and

individual combat skills. "Graduates return to their units to pass on these

skills." The website outlines the physical and mental qualifications required

to attend this leadership course. Ranger School accepts servicemen from all

services and all specialties. The single qualifying distinction is that all men

are eligible but not one woman is eligible regardless of her mental and

physical qualifications. Male chaplains and doctors attend Ranger School but

women fighter pilots, military police, artillery, and engineer soldiers are

excluded.

When Army leaders are asked why women are excluded from

Ranger School, the answer is that Ranger School is a sourcing mechanism for the

Ranger Regiment and Ranger billets and since women aren't assigned to these

positions they don't need to attend Ranger School. This is a grossly

disingenuous answer and is refuted by the evidence. Even before the combat

exclusion policy that prohibited women from serving in combat units was lifted,

Ranger School was widely understood to be a leadership course and many men who

undertake the course have no intention of joining the Ranger Regiment and are

never assigned to a Ranger billet. The soldiers that the 7th ID intelligence

brigade was recruiting were not headed to a Ranger unit. They were expected to

return to their intelligence brigade and use their newly acquired skills to

improve their units.

Furthermore, Ranger School completion becomes a performance

evaluation discriminator in the minds of many operational commanders. As a

member of a chaplain's promotion board recently observed, chaplains who wear

the storied Ranger tab are consistently rated higher than their non-Ranger qualified

peers. Ranger School may make these chaplains better leaders or it may simply

be that they are perceived to be better leaders as a result of being Ranger

qualified. Regardless of the reason, women who are never afforded the

opportunity to attend Ranger School are at a disadvantage when compared to

their Ranger-qualified peers.

Women attend and graduate from the challenging Air Assault

and Airborne courses. Some go on to become High Altitude, Low Opening (HALO)

parachute jump masters. Women become Pathfinders where they are dropped into

remote locations and navigate through harsh terrain to establish day and night

landing zones to facilitate follow-on forces. In recent years, women became

Sappers after completing the grueling month-long Sapper course. Sappers are

soldiers who are trained in navigation and demolition techniques and are often

inserted behind enemy lines. These are tough schools and the Army has managed

to include women in all of them with no degradation of standards.

It has been one year since the combat exclusion policy was

lifted but women are still excluded from Ranger School. This should have been

one of the easy openings. Ranger School has long had well defined entry and

graduation requirements. There is no need to either validate or establish

non-existent standards. Standards already exist. Just open the school and let

women compete on an equal footing with men. Opening Ranger School now will give

women the opportunity to prove that they are soldiers capable of any test. It

will put to bed any lingering doubts about whether or not women can serve in

the combat arms. If women can graduate from Ranger school, then surely they can

capably serve in combat units.

Ellen Haring in a West

Point graduate and a colonel in the Army Reserve. She is a senior fellow at

Women in International Security.

What says revolutionary Maoism better than a pure gold statue of the guy?

The

Chinese press revealed that last year, when police raided the house of Chinese

Lt. Gen. Gu Junshan, they seized tons of luxury goods, including an expensive

wine cellar and a pure gold statue of Mao Zedong.

January 15, 2014

The Future of War (II): As the nature of war changes, the familiar dividing lines of our world are blurring across the board

By the Future of War

team, New America Foundation

Best

Defense office of the future

Changes in the nature of warfare profoundly shape both the manner

in which the state is organized and the law itself. An obvious example of this

is how the adoption of gunpowder warfare and the emergence of small standing

armies helped to produce the absolute monarchies of the 16th and 17th

centuries. In turn, the levee en masse -- the mass mobilization of

conscripts -- by Napoleon's revolutionary armies helped spell the beginning of

the end for those monarchies. The

need to raise and maintain ever-larger armies also required the creation of the

apparatus of the modern state such as a census, universal taxation, and basic

education.

Today, we are at another major inflection point, one in which technology is reshaping the way wars

are fought. The future

of warfare will be shaped by the role of ever-smaller drones; robots on the

battlefield; offensive cyber war capabilities; extraordinary surveillance

capabilities, both on the battlefield and of particular individuals; greater

reliance on Special Operations Forces operating in non-conventional conflicts;

the militarization of space, and a Moore's Law in biotechnology that has

important implications for bio-weaponry.

Consider a few examples:

The Manufacture of Life: Scientists can now manufacture living

organisms, including new viruses. These breakthroughs are useful to scientists

but also, potentially, to terrorists or unscrupulous states.

Drones: Drones allow us to assassinate individuals a world away by remote

control and they are proliferating in unexpected ways. Already, the brief

monopoly that the United States, Britain, and Israel have had on armed drones

has evaporated. China

took the United States by surprise in 2010 when it unveiled 25 drone models at

an air show, some of which were outfitted with the capability to fire missiles.

This year, the Chinese disclosed that they had planned to assassinate a

notorious drug lord hiding in a remote part of Burma with an armed drone but

opted to capture him instead.

Just as

the U.S. government justifies its CIA drone strikes in Pakistan and Yemen with

the argument that it is at war with terrorists such as al Qaeda and its

affiliates, one could imagine that China might strike Chinese Uighur

separatists in exile in Afghanistan with drones under the same rubric.

Similarly, Iran, which claims to have armed drones, might attack Iranian

Baluchi nationalists along its border with Pakistan.

Yet the

Pentagon, with characteristic short-term thinking that focuses too much on

"readiness" and not enough on "preparedness," seems lately to be shying away

from fully embracing drones, cutting spending on them while continuing to

devote billions of dollars to manned warplanes.

Cyber-siege: One potential technique in the new world of warfare is what New

America's Director of the Open Technology Institute Sascha Meinrath terms

"cyber-siege"

war. Presently, we conceptualize most hacking attacks as opportunistic, meaning

they concentrate on the softest identifiable targets. However, Meinrath

predicts that an enemy undermining the core functionality of our computer systems

could harm our increasingly tech-reliant society and that would then lead to a

more massive, far-reaching, and invasive cyberattack. The NSA's multi-year

strategy to undermine commercial encryption is just such a "cyber-siege" on

fundamental technological functionality. Meinrath believes we must assume that

other nation states and non-governmental forces are working along the same

lines. Is China, for instance, putting "backdoors" in hardware chipsets?

A cyber-siege

isn't won or lost based upon singular battles. Instead, we have to think about

how we're bolstering defenses writ large -- something that the United States is

not doing. Instead, the U.S. focus is disrupting small networks of

cyber-criminals. If the United States really wanted to protect the country and

the privacy of individuals from what's next, we'd be thinking in terms of

standardizing and "hardening" computer systems for everyday products (i.e.,

cars, appliances, home security systems, etc.); compartmentalizing data (to

prevent grabbing huge amounts of customer data at once); disclosing when

breaches occur (to acknowledge weaknesses and shore up defenses), and

protecting consumer data (whether health, banking, or social networking).

The scientific manufacture of life, the proliferation of drones,

and increasing opportunity of cyber-siege are just the tip of the iceberg. The

evolution of surveillance technologies, space weapons, and autonomous unmanned

systems of all sorts are also transforming warfare.

New technologies have also democratized mass violence, enabling

non-state actors to use and threaten lethal force on a scale previously

associated only with states. The 9/11 terrorist attacks shattered the

comfortable assumption that the United States faced only conventional state

adversaries. Since 9/11, the United States has fought conflicts of various

types against a variety of networks of non-traditional combatants, such as al Qaeda

and its allied groups in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen.

New America's "Future of War" project will not only look at how

wars will be fought but who will fight them -- and what rules will

govern the conduct of warfare.

Taken together, recent changes both in the technological drivers

of warfare and the enemies we face have erased the boundaries between what we

have traditionally regarded as "war" and "peace," military and civilian,

foreign and domestic, and national and international.

They have blurred the

lines between military law and

criminal law as the United States grapples with how to prosecute members of

al Qaeda who are part of a criminal enterprise that is also at war against the

United States and her allies.

They have blurred the

lines between military and civilian roles, such as the delivery of aid and

development. Consider the case of members of Provincial Reconstruction Teams in

warzones such as Afghanistan where they are essentially armed social workers.

They have blurred the

lines between public and private. Private contractors now handle a

considerable number of military functions that would previously have been the

purview of government employees. This raises a thicket of thorny legal and

accountability questions: For instance, could a contractor involved in the CIA

drone program be charged with murder if a civilian is killed in a drone attack?

They have blurred the

lines between the military and the intelligence community. It is no longer

even a cause for much comment that the CIA has become something of a

paramilitary organization, which, even taking the most conservative estimates,

has killed around 3,000 people in drone strikes in Pakistan and Yemen under

President Obama alone.

They have blurred the

lines between domestic and foreign. The most well funded Pentagon spying

agency, the NSA, was set up to counter the threat posed by the nuclear-armed

Soviet Union. In part due to the near-impossibility of cleanly distinguishing

between "domestic" and "foreign" communications, the NSA has now collected the

telephone metadata of hundreds of millions of ordinary American citizens.

They have eroded

traditional conceptions of sovereignty. With more and more states

developing technologies that enable them to "reach inside" other states with

relatively little immediate risk (whether using drone technologies, space-based

surveillance systems or cyber tools), the nature and meaning of sovereignty is

being transformed.

And so on. As Charles Tilly observed, "War made the state, and

the state made war." If war is changing, then the state will change, and so will the

non-state organizations that increasingly challenge those states and the

international organizations that seek to channel state behavior. What these

changes will look like is hard to predict, but they are likely to be as

profound as the shift from the pre-Westphalian world to the modern world of

nation-states.

The Future of War project is led by Peter

Bergen, director of national security studies at the New America

Foundation, and the author of several

books. This series

was drafted by him and the team's other members: Rosa

Brooks, Anne-Marie

Slaughter, Sascha

Meinrath and Tom

Ricks.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers