Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 221

November 1, 2011

Colin Gray's essays on strategy (II): Why 3 strategic classics remain relevant

In his 14th essay, Colin

Gray makes a good argument that all you really need to do to understand

strategy is read and re-read Thucydides, Sun Tzu, and Clausewitz. "These three

books constitute the strategic canon," he advises.

He adds an interesting thought: "It is only the generality

of strategic ideas in the three classics that saves them from utter irrelevance

to the supremely pragmatic and ever changing world of the practicing strategist."

I'd go a step farther and say that their very generality is what makes them so

useful. War is chaotic, crammed with startling details and unexpected turns. In

2004 and 2005, as I was writing Fiasco

and so trying to understand the war in Iraq, I took all those details and

developments and sat down with Clausewitz and T.E. Lawrence for a month. Both

books helped me "make sense" of what I had seen -- Clausewitz in strategic terms,

Lawrence more on the tactical and cultural.

Cronin reviews a new RAND report on the possibility of a U.S. conflict with China

It is always nice to see a

RAND document that actually come to some conclusions, however tentative.

Maybe they are outgrowing the motto, "RAND -- Providing an intellectual hospice

for the conventional wisdom."

By Patrick Cronin

President, Best Defense Academy of Frenemy-American

Relations

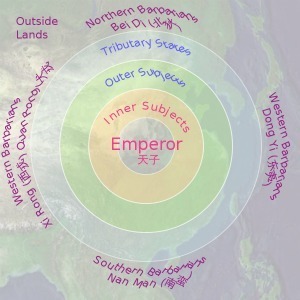

China

appears well on its way to becoming America's next peer competitor. Over the

next twenty years, a modernizing People's Liberation Army will challenge

regional militaries and better keep foreign powers out of its near seas. As a

result, according to a new RAND report, the

U.S. Armed Forces will "become increasingly dependent on escalatory options for

defense and retaliatory capabilities for deterrence."

In "Conflict with

China: Conflict, Consequences and Strategies for Deterrence," James

Dobbins, David Gompert, David Shlapak, and Andrew Scobell consider triggers for

U.S.-China conflict and their operational and strategic implications.

The paper first examines "occasions for conflict" and

includes situations involving the Korean

Peninsula, Taiwan,

cyberspace, the South China Sea, Japan,

and India.

The scenarios, all judged to be plausible if unlikely, are listed in descending

order of probability, with conflict over North Korea thought to contain

"significant potential" for escalation.

Similar hazards entail the other potential confrontations

considered by the authors. Thus, the discussion on cyberspace suggests how

China's putative success in stealing others' electrons could precipitate

kinetic action. For instance, a Chinese attempt to disrupt U.S. communications and intelligence could

catalyze attacks on satellites and a blockade on China's vital sea lines of

communication. The latter refers to an abiding Chinese concern over its

so-called "Malacca dilemma," a reference to how closure of the critical Malacca Strait

joining the Indian and Pacific oceans might cripple resource-dependent China. Such a

scenario could well be casualty-free and yet bring about monumental economic

loss and regional upheaval.

The 25-page report's sheer economy of verbiage is one of its

strengths. While the authors no doubt could have amplified on the scenarios -- from

the East China Sea to the Indian Ocean or Iran to Pakistan -- an exhaustive

review of potential conflicts would have added little to the conclusions. Their

main interest is to think through operational implications of current trends. [[BREAK]]

And

the impact on future military operations is sobering. A reduced ability to

project power to defend allies and partners in East Asia

would drive our military procurement in the direction of "enhanced weapons,

ranges, geography, and targets" to ensure the survivability of our platforms

and bases. Further, we would need improved means of eliminating critical "Chinese

forces, launchers, sensors, and other capabilities," even eventually "Chinese

satellites and computer networks."

Chinese

military gains appear to target the Achilles' heel of U.S. modern networked battle

systems, and it is a logical deduction to assume a comparable set of Chinese

capabilities could be similarly put at risk. But looking ahead that may be as

good as it gets, as the authors assume an almost inexorable Chinese ability to

further close the qualitative military gap with America. "Barring unforeseen

technological developments that assure survivability for U.S. forces and C4ISR," they write, "it will not

be possible or affordable for the United States to buck these

trends."

This

will leave the United States

with a bleak choice between escalation (and deterrence based on Chinese fear of

escalation) and acquiescence to a rising China. Escalation is inherently

risky and could lead to nuclear war, and the latter cedes American power and

hands to China

precisely what it may wish to achieve with its growing military might.

The

throwback to bipolar strategic logic will seem anachronistic to some but is

arguably a helpful refresher on just what a rising China will mean with respect to our

military preponderance in the Asia-Pacific region. Unfortunately, especially

without a renewal of the American economy in the years ahead, the United States'

options for dealing with these challenges are somewhat underwhelming.

The

authors focus on three ideas: economic interdependence, building partnership

capacity, and drawing China

into more cooperative security endeavors. All of these are unobjectionable and

sound general activities to be undertaken. The high degree of economic

interdependence is certainly a barrier to conflict. As one leading Chinese

scholar recently told me, "We are not worried about military tensions provided China stays on

track to become your largest trading power." But it would have been useful if

authors had also considered how such strong economic ties could make it seem

safer to conduct a balance of power competition, as geopolitics and

globalization coexist.

The

second notion of building partnership capacity is worthwhile. However, it also

has serious limits, because every nation in the region wishes to avoid

offending a rising China

that is also its largest or second largest trading partner. It is easier for Vietnam

to buy Russian Kilo-class submarines

than front-line American hardware. Similarly, note that U.S. military transfers to the Philippines have thus far been limited to a

1960s-era Hamilton

class Coast Guard cutter). As with pressure on U.S.

arms sales to Taiwan, China may well believe that over time it can

demand reduced U.S.

military cooperation with its neighbors.

The

authors also call for modifying the U.S.-China strategic relationship. That is

fine, too, but before one does that, it's worth reflecting on whether any

coherent framework exists and, if so, whether that framework is genuinely

shared across policy elites even within the current administration. It is here

that the authors' call for persuading China to buy-into a more cooperative relationship

in the region is sensible if not all that compelling (and ultimately the test

is whether such reasoning is compelling to the Chinese, not other Americans). At

a minimum, we should not delude ourselves into thinking that China will embrace our pivot to Asia if only we

invite China

to join in more multilateral security ventures. Chinese leaders are simply apt

to see any strengthening of America's role in the region as antithetical to

their national interests. As my colleague Robert Kaplan has written, the

Indo-Pacific region is witnessing a triumph of realism.

In

sum, the idea of mutual economic assured destruction, investing in partners,

and cooperative security are at best necessary but insufficient elements of a

strategy. They hardly seem a substitute for the kinds of new forces and

operational adaptations implied in the report's analysis. Economic cooperation

alone is insufficient to bar the outbreak of hostilities. So, we can agree with

the authors that while the likelihood of conflict between the United States and China should not be exaggerated,

neither should it be summarily dismissed. The distillation of the authors'

thinking incorporated into this useful paper should be a starting point for

deeper analysis.

October 31, 2011

My favorite Marine photo from WWII

By Eric

Hammel

Best Defense guest photo curator

Tom has kindly asked me to select and

discuss my "favorite" photo from my latest -- and probably final -- book,

Always

Faithful: U.S. Marines in World War II Combat, The 100 Best Photos.

Each photo in the book bears a caption that identifies only the operation in

which it was taken. It is left to the reader to decide what they see in the

photo, not read what I think.

I don't have a favorite. I selected

each of them from a collection numbering in the thousands, which I have been

over many times during the past six or seven years. But some have more meaning

to me than others. The selection you see here is one that holds great personal

significance. It is of a handful Marines about to crest a hill on Okinawa. My

late father fought on Okinawa as a U.S. Army combat medic attached to an infantry

company. He was wounded and evacuated. He arrived home just in time to start my

personal ball rolling. I think of my father every time I see this photo.

What I see is a technically deficient

photo; it's overexposed. But it perfectly captures an important truth about

combat, and life: beware what's on the other side of the hill. A little of the

body language the combat photographer captured suggests the caution veterans

exhibit when they sense or anticipate danger. But look more closely: they're

up, they're advancing, they're ready for anything. In a moment they will be

gone.

" ...will be gone." On a meta

level, this photo represents -- to me -- the imminent passing of the World War

II generation. These were the men who raised me, who taught me, who mentored

me, who inspired me. And, for the most part, they have already advanced into

the great light that will take us all -- willingly, bravely, realistically,

with heads held high.

21: For real this time

The 21st Navy skipper

of the year was fired, for "poor personnel management." (As I noted the other day, that guy down in Norfolk actually had been counted by Navy Times as fired back in the spring, so he wasn't no. 21.) This time it was

the CO of the minesweeper Fearless.

Also, the skipper of the USS Momsen,

who had been charged with rape, etc., pleaded guilty and was sentenced

to 10 years behind bars, with the understanding as part of the plea that he

would serve 42 months.

Retired Navy

Capt. John Byron comments:

In the scheme of things, this is a pretty tough

sentence. 42 months incarceration, probation for the rest of the ten years, maybe

registered sex offender, loss of some benefits and retirement, professional

disgrace, doubtless fallout in his family life. There are many other ways this

could have been handled, from start to finish. That it was seen as an egregious

felony is credit to the Navy system and this person's chain of command.

The plea deal kept the two women off the

witness stand. Would guess that was a major consideration for the prosecution.

The message this sends to the fleet is inescapable: we meant what we said.

I'm

proud of my Navy.

(2 HTs to RD)

Van Creveld's deceptively simple for formula for measuring military power --and Peter Mansoor's rip on van Creveld

For some reason, in my research for my book on American

generalship, I read a lot about military effectiveness over the summer -- parts

of the

classic Millett and Murray series and of John Ellis' Brute

Force, plus the conclusion of Martin van Creveld's

Fighting

Power. I finally realized that the issue was not really central to my

book, but the books still were worth reading.

Here is van Creveld's deceptively simple formula: "the

military worth of an army equals the quantity and quality of its equipment

multiplied by its fighting power." (P. 174) (Paul Gorman had something

similar in his on-line papers.) The question, of course, is how does one

create and assess this fighting power? -- and that issue is what his book

explores.

That said, check out this crack by Professor Doctor Colonel Peter Mansoor

on page 255 of The

GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of American Infantry Divisions, 1941-1945:

Few American commanders of the World War II era would agree

with authors such as Martin van Creveld that the Germany army was more

effective. While the cream of the Wehrmacht, the panzer and panzer grenadier

divisions, were more combat-effective organizations and a match for the divisions

of the Army of the United States, the bulk of the German army was not composed

of these units. The average German infantry division could not defeat an

American infantry division in battle, while American infantry divisions consistently

proved their ability to accomplish their missions against the enemy divisions

in their front.

October 28, 2011

Colin Gray's 40 maxims on strategy: 3 big reasons the Americans screwed up in Iraq

40 Maxims on Strategy

would be a much better title for Gray's book than the actual one, which is Fighting

Talk: Forty Maxims on War, Peace and Strategy. I was put off by that

title but bought the book after I saw Gen. Mattis recommend it.

It is good stuff. Here are some of the things I underlined:

The socio-cultural context has been emphasized here because

it has been, and remains, the prime area of strategic weakness in the behavior

of the U.S. superpower.

(p. 5)

... strategy must convert one currency (military behavior)

into another (political effect).

(p. 11)

Competent strategy is all but impossible in the absence of a

continuous dialogue between policymakers and soldiers.

(p. 12)

Tom again: These aren't the only reasons, of course. But

they are a good start.

Gray also made me think I should go back and read Thucydides

again. Last time I used a tiny print Penguin Classic edition because I was

reading it on my commute on the Metro. This time I think I will try the big

fat Landmark edition with all the maps, which I have lying around

somewhere.

America is muddling through middling relationship with the Middle Kingdom

By Peter Bacon

Best Defense Academy of Frenemy-American Relations

At SAIS the other day, the Kettering Foundation and the

Institute for American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS)

held a high-powered conference on the future of U.S.-China relations, featuring

pretty much all the big names in the China racket. If you weren't selected to

be one of the illuminati, here is what you missed:

--Professor David Lampton of SAIS summed up the conference's

assessment of Sino-American relationship as "not in the best of times, but not

in the worst of times." Both Professor Lampton and Rear Admiral Eric McVadon

both identified believe that the relationship has evolved over the past decades

from a one-dimensional, anti-Soviet Cold War partnership to a "three-legged

stool," of security, economic, and culture relations. Elites within both

countries bolstered this relationship: Tao Wenzhao, a senior fellow at CASS,

argued that the recent meetings between elites such as Hu Jintao and President

Obama, and between Joe Biden and Hu's putative successor Xi Jinping augured

well for future

Sino-American relations. Indeed, Wenzhao remarked that one Chinese official

observed that "Mr. Jinping [had] never spent so much time with a foreign guest"

as he did with Biden. The conference's keynote speaker, former National

Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, similarly identified the Hu-Obama

communiqué issued during the two leaders' meeting as "a real blueprint of

strategic objectives shared and 34 tangible paragraphs elaborating on them and

tasks ahead for the relationship."

--The panelists overall still felt quite uneasy about the

future of the Sino-American relationship. Stephen Orlins, President of the

National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, memorably remarked on his experience

on Chinese television when he was asked by a Chinese audience member "why every

U.S. policy was designed to oppose China's rise." Tellingly, Orlins continued,

"everyone in the audience [stood] up and [started] to applaud." Brzezinski,

similarly, wondered whether the anti-China rhetoric from the field of

Republican candidates could engender "a more Manichean vision of the world"

within the American government. Panelists on public perceptions of the United

States and China confirmed this: Yuan Zheng, a Senior Fellow from CASS, found

in studies from 2008 to 2010 that "ordinary Chinese have mixed feelings towards

the US, just as [ordinary Americans] with China." Indeed, he continued, "56 percent of

those Chinese surveyed felt that American policy was two-sided, geared towards 'cooperation

and containment.'" Andrew Kohut, President of the Pew Research Center, also

pointed out that 58 percent of Americans felt that the United States needed to get

tougher with China on trade, while 56 percent of Americans simultaneously felt that

the United States and China needed to build better relations.

--Panelists and speakers at the conference argued that these

ambivalent tensions necessitated a global condominium between America and

China, or, in the words of Brzezinski, "to act towards each other as though we

were part of a G-2 without proclaiming ourselves to be a G-2." This "basic generalization"

of Brzezinski followed on statements made by other speakers such as David

Lampton and Tom Fingar of Stanford University who both argued that without

Sino-American cooperation and leadership, problems of international economic

management, collective security, or climate change would not be dealt with.

Fingar further argued that each power needed to pursue this cooperative

partnership even if we had not reached a state of mutual trust between the two

powers. The "very real, very now" nature of issues such as climate change and

its impact on national security and ever-changing threats to global security

necessitated a partnership even as publics and elites remained distrustful of

each other.

Rebecca's war dogs of the week: Stupid Labradors become bilingual aces

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense goddess of dogginess

It

seems that India is attempting to infuse its military workings dogs with a

little James Bond style mojo.

According

to reports out this week, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) is claiming to

have a one-of-a-kind elite war-dog team. Details of

this new force, comprised of six Labrador Retrievers called Bomb Drop Dogs

(BBD) who've been trained at the ITBP's National Training Centre for Dogs,

range from the intriguing to the insignificant bordering on painfully obvious.

According

to a report in the Telegraph, India's BBDs boast a

variety of Mission Impossible worthy skills including the ability to: "carry

explosives in their teeth, sneak into terrorists' lairs, drop remote-controlled

bombs, hide secret cameras, understand instructions in English and Hindi and

interpret body language."

But

in a statement to The Pioneer that outlined the scope of this

program and its aims, the Additional Director General of the ITBP, Dilip

Trivedi, said that the team of six BBDs would go a

long way to "minimise casualties of our soldiers" because BBDs could "approach

the target and secretly plant explosives. When it goes off, the terrorists

would be exposed and thus easily targeted. As they are smaller in size to men,

these canines are not easily spotted by the enemy. According to the situations,

they further lower themselves and approach targets by crawling." (This is the

painfully obvious part, History of Military Working Dogs 101.)

Still,

another, more compelling point of view was given to the Telegraph by the Indo-Tibetan Police Force's spokesman, DK

Pandey (who was also sure to make assurances about the focus on the dogs'

safety):

It's

the first time in India such a dog squad has been successfully trained in

dropping of bombs, video and audio devices and other equipment inside enemy

hideouts. They will be carrying them in their mouth and drop it inside the

suspected hideout and when [the dogs] report back to their handler and

commander, then only the next step will be taken -- triggering the blast through

remote control,' [Pandey said.]

While

noteworthy, I'm not ready to concede that India's BBDs yet have a paw up in the

wide world of MWDs. While I don't doubt that these Labs are highly trained or

that these dogs are capable of learning such intricate tasks, India's BBD force

still appears to be in the early stages. There are no reports that this

training has been put to use or proven successful and effective in the field.

Let's put this one in the wait-and-see pile.

Rebecca's war dogs of the week: Stupid Labradors become bilingual James Bonds

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense goddess of dogginess

It

seems that India is attempting to infuse its military workings dogs with a

little James Bond style mojo.

According

to reports out this week, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) is claiming to

have a one-of-a-kind elite war-dog team. Details of

this new force, comprised of six Labrador Retrievers called Bomb Drop Dogs

(BBD) who've been trained at the ITBP's National Training Centre for Dogs,

range from the intriguing to the insignificant bordering on painfully obvious.

According

to a report in the Telegraph, India's BBDs boast a

variety of Mission Impossible worthy skills including the ability to: "carry

explosives in their teeth, sneak into terrorists' lairs, drop remote-controlled

bombs, hide secret cameras, understand instructions in English and Hindi and

interpret body language."

But

in a statement to The Pioneer that outlined the scope of this

program and its aims, the Additional Director General of the ITBP, Dilip

Trivedi, said that the team of six BBDs would go a

long way to "minimise casualties of our soldiers" because BBDs could "approach

the target and secretly plant explosives. When it goes off, the terrorists

would be exposed and thus easily targeted. As they are smaller in size to men,

these canines are not easily spotted by the enemy. According to the situations,

they further lower themselves and approach targets by crawling." (This is the

painfully obvious part, History of Military Working Dogs 101.)

Still,

another, more compelling point of view was given to the Telegraph by the Indo-Tibetan Police Force's spokesman, DK

Pandey (who was also sure to make assurances about the focus on the dogs'

safety):

It's

the first time in India such a dog squad has been successfully trained in

dropping of bombs, video and audio devices and other equipment inside enemy

hideouts. They will be carrying them in their mouth and drop it inside the

suspected hideout and when [the dogs] report back to their handler and

commander, then only the next step will be taken -- triggering the blast through

remote control,' [Pandey said.]

While

noteworthy, I'm not ready to concede that India's BBDs yet have a paw up in the

wide world of MWDs. While I don't doubt that these Labs are highly trained or

that these dogs are capable of learning such intricate tasks, India's BBD force

still appears to be in the early stages. There are no reports that this

training has been put to use or proven successful and effective in the field.

Let's put this one in the wait-and-see pile.

October 27, 2011

Hey, it turns out that income inequality really is a major national security issue

About a year

ago, when I began thinking aloud in this blog

about income inequality as a national security issue, I worried if that

argument was a stretch. So I was pleased to see George Packer sprinkle holy water on it in the new issue of Foreign Affairs:

This inequality is the ill that underlies all

the others. Like an odorless gas, it pervades every corner of the United States

and saps the strength of the country's democracy. But it seems impossible to

find the source and shut it off. For years, certain politicians and pundits

denied that it even existed. But the evidence became overwhelming. Between 1979

and 2006, middle-class Americans saw their annual incomes after taxes increase

by 21 percent (adjusted for inflation). The poorest Americans saw their incomes

rise by only 11 percent. The top one percent, meanwhile, saw their incomes

increase by 256 percent. This almost tripled their share of the national

income, up to 23 percent, the highest level since 1928.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers