Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 217

November 17, 2011

Col. Abrams on firepower and mobility

While

I was doing some hole-plugging research the other day at the Army's great

Military History Institute (and also having a few Belgian beers with a few Best

Defenders), I read Col. Creighton

Abrams' 1953 Army War College paper on "Mobility and Firepower."

The

paper is well done, reflecting critical thinking and informed analysis. I

wouldn't call Abrams an intellectual--he actually writes better than most of

that sort, with clear sentences and verbs pushing nouns along the page. "There

is more to mobility than a truck that will go 40 mph or a tank that will go 25

mph. It is more than good planning, more than tanks themselves. It is even more

than movement alone, because there must be power with movement." (P. 7)

So

what is firepower and mobility all about? Not unlike Andy Krepinevich, Abrams

emphasizes organization (logistics, reconnaissance, protection by infantry),

and communications. "In the German attack in France, in World War II, the

French had twice as many tanks as the Germans (4500-2200). In addition, the

French tanks were superior in armament and armor. Guderian credits much of the

success of the German operation to its superior communications, an item on

which the Germans had spent much time and effort." (P. 9)

By

the way, to file under the "it can happen to anybody" heading: The printed

title page of the paper identifies Col. Abrams' branch as "Infantry." This has

been crossed out and corrected. I liked this because I used to remind myself as

a reporter when I was getting messed around by the Army that it wasn't personal,

they treat everyone this way. Even old Thunderbolt. (Except for when they

basically threw out my FOIA requests filed when I began writing 'Fiasco.' In

that case, I suspect that for several years during the reign of Rumsfeld the

Loud, the Pentagon engaged in reckless disregard for the law in the way it

handled FOIA filings. After the book was published I got a response basically

telling me to get lost with my FOIA requests.)

The legend of Squeaky Anderson, the poacher of Alaska -- and a Navy officer

Another

thing I read at Carlisle was the oral history of Lt. Gen. George Forsythe, who

during World War II served for a bit in Alaska, and in the 1970s helped create

the All Volunteer Army.

Forsythe

was impressed that when the Navy began planning amphibious operations in the

Aleutians, it sought out a fish poacher named Squeaky Anderson,

who made his living seining in areas that legally were limited to fishing by

Native American tribes, as well as by poaching sea otter pelts and such, and

sometimes selling rotten salmon, and perhaps

walking off with anything that wasn't nailed down in the harbor. In the

process of poaching and evading the Coast Guard, Forsythe said, Anderson had

learned all the rocks, reefs, currents, and hiding spots along the islands. The

Navy made him a lieutenant commander, and Squeaky brought along his little

fishing boat on a lot of the subsequent operations, in part because that is

where he kept his booze.

Apparently

the short, fat Anderson went to become a respected beachmaster in several

Pacific landings, most notably Saipan and Iwo Jima, where he was instant

recognizable for his usual uniform of cut-off shorts, dirty baseball cap, black

shoes, and red face.

A few words in defense of West Point: They sure do Model United Nations well

I've

bashed West Point and the rest of the professional military educational

establishment quite a bit in this blog, so I welcomed this chance to let a CNAS

colleague say a few nice words about the USMA.

By

Peter Bacon

Best

Defense guest columnist

Last

week the program Parks and Recreation showcased one

of the nerdiest extracurricular activities of all: Model United Nations.

This activity, known for its geeky high school and college students and its

focus on international affairs, offers some surprising insights into the state

of civil-military relations and international affairs education in this

country. I know -- I spent three years in college competing as a delegate.

At the college level, some of the best teams for Model UN

are from our military academies. West Point's team is consistently rated as one

of the best programs in the country; the other service academies that field

teams, the Air Force and Naval Academies, always put up solid teams and

delegates. In part, these delegates excel because they are instructed in

leadership in the classroom and on the parade field. Nice uniforms, including

the renowned cadet gray, also help make a good first impression. But most of

all, these delegates excel because they know just that much more about the military-aspect of international affairs

than the average college student. Civilian delegates understand the bare

minimum of military culture and tactics: civilians will illustrate their basic

grasp by making arguments in committee amounting to "bomb this, not that" or

"move X troops here." Service academy delegates, meanwhile, will explain

complex military and diplomatic operations to committees ranging from 30 to

300. Routinely, this means that civilian students fail to question any

military-related policies of West Point or Naval Academy delegates. As a

testament to this, most committees will give a military delegate a portfolio

related to the military, such as Secretary of Defense or a military commander.

It's not hard to see why this happens: civilian students

simply do not learn anything about

this facet of our society. Foreign policy classes focus more on flighty theory

than actual practice. History classes barely focus on hard

military or diplomatic history. When I led delegates as an undergraduate,

one of the things that I struggled with was teaching freshmen straight out of

high school about general military capabilities simply because they knew so little about the topic.

The service academies, specifically West Point, are trying

to correct this educational imbalance: West Point's Model UN team set up its own

conference, dedicated primarily to educating civilians about the military.

I had the privilege of attending the conference in April: the Cadets made a

great effort to create realistic committees and instruct civilian students

about the military. From panels and speakers to eating alongside cadets and

learning about military culture and doctrine, the conference was, by the

accounts of my teammates, both "fantastic" and "eye-opening."

West Point has hopefully set a precedent that will follow:

directly engaging civilians, in an era when few ever interact at length with

members of our military, may be the only way to get them educated about

military affairs.

November 16, 2011

How to fix the Army in 66 easy steps (I)

By "Petronius Arbiter"

Best Defense department of Army affairs

A few small things, some annoyances, and some big fixes that

could make a good Army better:

Philosophy

CSA

position needs to be Commandant-like, commanding the Army, not just directing

the Army staff, assigning Generals or formulating the Army budget. Army

structure should empower him to do so.

Don't

be afraid to admit mistakes, acknowledge that the institution made a mistake

and then fix it, even if it means going back to the way something was in the

past or even getting a black eye.

Do

not, I say again, do not, have a regulation/policy/or law that you are

unwilling or reluctant to enforce; examples, enforcement of the height/weight

program, or the prohibition of cell phone use in moving autos. To do less is to

violate the first principle of leadership and makes a mockery of the

institution. Enforce unilaterally, not out of convenience. Perfect example is

the inability to enforce the Army height/weight standards in order to maintain

force structure manning for deployments. Cynics develop over things like that.

Eliminate

NCO business or NCO time as an institutional mantra. It becomes Army business

or all our business, focused on one solution and focus.

Do

nothing in the Army that does not build soldiers' and officers' confidence in

themselves and their units.

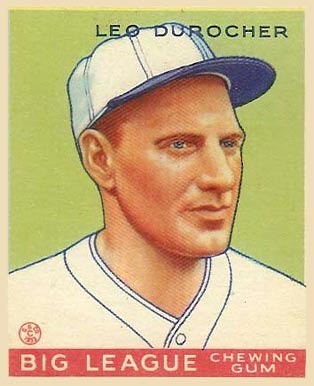

Gray and strategy (V): A rare lapse in his understanding of the American psyche

Colin

Gray concludes his 30th maxim, about the persistence of thuggishness in

world politics, with this quotation: "Nice guys finish last." He attributes

this to "Popular American saying."

This is one of the rare lapses in his

book, and a bit ironic given his emphasis on the need for cultural

sensitivity in making and implementing strategy. In this case, he gets the

words right but the attribution wrong, and if you know your baseball history,

that's significant. The crack about "nice guys finishing last" is not a folk

saying broadly popular with Americans, it was an riposte made by Leo Durocher,

a brawling baseball manager with a distinctly dark view of the world -- and of how to play

baseball: "Win any way you can as long as you can get away with it." So I

would say that the comment isn't so much reflective of American views -- which

tend to be more optimistic, law-abiding and meliorist -- as of the hard-bitten

minority that believes that to get along in the world, you have to kick, bite

and gouge every inch of the way. Or, as Durocher once confessed, "If I were

playing third base and my mother was rounding third with the run that was going

to beat us, I would trip her."

North Korea: Land of totalitarian magic

By Joseph Natividad

Best Defense Pyongyang deputy bureau chief

An English literature professor from Southern California by day and a

world-class magician by night, Dale Salwak holds the distinction of being the

only American invited to perform his act in North Korea. At SAIS recently,

Salwak chronicled his experiences in Pyongyang in 2009 and this past April for

the Grand Magic Show, the largest ever in the country's history. His

perspective on North Korea offered a look beyond stereotypes of a totalitarian

system, mass famine, and nuclear proliferation, and focused instead on magic as

a great leveler which emphasized entertainment value before political

differences between two countries.

--Magic, as a trade, is taken very seriously in North Korea. Similar in

structure to the Chinese system, admission into its exclusive society is

followed by a father-son bond of lifelong apprenticeship. Isolated from the

West and having limited or no access to DVDs, books and the Internet, North

Korean magicians have devised their own methods to magic that have long been

known to performers like Salwak. A typical range of acts includes balancing

telephones on handkerchiefs and life-sized dolls performing choreographed dance

routines to traditional music. The local performers Salwak encountered on his

trips cherished every new trick acquired and pleaded with him to share current

"world trends" on magic.

--The culmination of Kim Jong Il's investment in the arts took place this past

April at the Grand Magic Show, a tribute to the late Kim Il Sung. Like his

father, Kim Jong Il appears to hold a great interest in magic and the circus,

dating back to the country's early history of Soviet influence. In a place

where high-tech entertainment is hard to come by, the Grand Magic Show dazzled

a crowd of 150,000 at May Day Stadium, which is the site of the Arirang Games,

an annual two-month-long gymnastics festival also in honor of Kim Il Sung. As a

spectator at the Grand Magic Show, Salwak watched as the country's most famous

magician, Kim Chol, appeared in a cloud of smoke and fireworks, forcing a bus

full of giddy local residents to levitate several feet above the ground, and

later, make a horse, an elephant and a helicopter materialize out of thin air.

What would have otherwise invoked a roaring response from a typical American

audience, the crowd respectfully cheered with subdued, tepid applause.

November 15, 2011

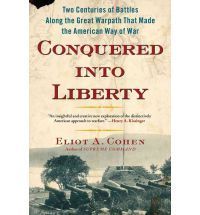

The Best Defense interview: Cohen's new book about the wars of the Great Warpath

Last week I

participated in a discussion of Eliot

Cohen's new book about America's warpath between Albany, New York, and

Montreal, Canada. One of the subjects was the similarity between that era and

today's, with sustained limited wars provoked by acts of terror. Cohen made a

couple of comments that struck me:

-- When Champlain

traveled with Indians south from Canada into hostile territory, "it's not

Champlain who is the actor, it's the Indians who are the actors. The Indians

are manipulating him." Likewise, these days, it's not always about us. In the

post-9/11 world, "we are a powerful piece often being moved around their

chessboard."

--The French

did much better than the British/Americans in dealing with the Indians -- but

eventually the British/Americans got "good enough" at it to use their other

advantages to prevail

--"One of

the great strategic virtues is empathy."

I asked an

old friend to interview Professor Cohen about his new book:

Magua:

Were you inspired to write this

book by the movie version of 'Last of the Mohicans'? If not, why not?

Eliot Cohen: No, no, no. The movie is

not all that great, and James Fenimore Cooper's book is pretty problematic too

-- wooden dialogue, implausible characters, unbelievable action. But he got the

landscape right. On the other hand, it's still in print, which is more than you

can say of most other books coming on two centuries since pub date. But there

is a kernel of truth here. Kenneth Roberts was a wonderful historical novelist

whom I read when I was a teenager, and between that and a visit to Fort

Ticonderoga at age ten I got hooked. Took me some four decades to go from

fascination to published book, however.

Magua:

Hmm. [Speaking Huron] Magua is glad this guy writes books better than he

reviews movies. [Returning to the white man's tongue] Tell us a bit about this

French-Canadian character who keeps popping up, would you?

EC:

That would be La Corne St. Luc. He led raiding parties

against the Americans in three wars (King George's War, the French and Indian

War, and the Revolution) although he also offered to join them when it looked

as though we were about to take Canada in 1775. He was a brilliant leader of

Indians and may have had a role in the massacre at Fort William Henry in 1757. In

1761 he figured New France was finished and set sail for France. He was

shipwrecked off what is now Cape Breton Island, saw his two sons slip out of

his grasp and drown just before he got on shore, pulled together the half dozen

survivors, built a fire, found some Indians to take care of them, and then hiked

fifteen hundred miles or so to Quebec -- in the dead of winter -- to get more

help. Smart enough to slip away from Major General John Burgoyne's army

invading New York from Canada in 1777, just before it was surrounded and forced

to surrender to the last man. Died in 1784, aged 73 (a very ripe old age by

contemporary standards) one of the richest men in Canada, with a pretty young

wife. Quite a guy.

Magua:

The French were in so much better a position militarily. How did they blow

their hold on North America?

EC:

Numbers had a lot to do with it -- there were only 80,000 French Canadians and

about fifteen times as many English-controlled colonists in the 1750s. But the

more important explanation is the Royal Navy, which pretty much throttled the

colony during the Seven Years (French and Indian) War, and the willingness of

the British to pour vast resources into the conquest of North America. By 1759,

when Quebec fell, there were easily four or five times as many British as

French soldiers in North America, and Quebec was cut off and starving. But the

French put up a ferocious fight, and might have hung on another year or so. And,

in the supreme irony, at the decisive battle outside Quebec in 1759 their

combination of French troops, Canadian militia, and Indians actually

outnumbered the British army (almost all regulars) under James Wolfe.

Magua: Is there a

lesson for our times here?

EC:

I am wary of the idea of lessons. What the book shows, though, is just how

deeply our way of war is rooted in our past. What is now the United States has

been involved in every major global conflict since the end of the seventeenth

century, and the Great Warpath was, in many ways the decisive theater for the

North American bits of those conflicts. A lot of the ways we think about and

approach warfare emanate from the two centuries I discuss in the book,

including the paradoxical notion that one can conquer a nation into liberty. On

that particular point, see the chapter about the siege of St. Johns in 1775.

Magua:

What's the one question you wish someone would ask about this book?

EC: What was the most fun

about researching and writing it? Two answers: (a) leaving behind the pundits

(particularly the monomaniacs and wingnuts) of contemporary political discourse

and spending time -- in my head, that is -- with some great historians and

truly remarkable historical characters, including La Corne St. Luc, Benedict

Arnold, Ethan Allen, and many more; (b) walking the ground, to include

snowshoeing the Battle on Snowshoes and sailing the battle of Valcour Island.

If the book inspires lots of people to go poking around the places I write

about, I will be delighted.

Wanat: It's back

The new issue of Vanity Fair has a good overview piece by Mark "Black Hawk Down"

Bowden about the

Wanat battle and its effect on those who fought it, oversaw it and

questioned it. Here's a link

to the article.

Meanwhile, Rand Corporation surfaces

with a report

on what Wanat might tell us about small unit operations in Afghanistan. I gave

it a skim and can't tell what, if anything, to make of it. I don't want to keep

on beating up on poor Rand, but I find their reports tend to be mushy. I read

so much stuff that I want people to get to their essential points clearly,

quickly and emphatically -- as Col. Creighton Abrams did in an Army War College

paper that I was reading yesterday in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. More on that

later.

Ten tips for that Marine staff sergeant: Or, what I learned about life on terminal leave

Here's a response to yesterday's

query from a Marine staff sergeant about what today's job market it like.

It is written by a Marine officer who recently made the leap to the civilian

workplace.

By Sydney Farrar

Best Defense guest advice columnist

1. Learn to market yourself in the language of

the business world. Many Marines and veterans struggle with transposing their

experiences, i.e. billet accomplishment, into the language of corporate

America. The military may not like to call officers and SNCOs "managers" but in

the eyes of many in the business world that is exactly what we are. I know we

are "leaders," but don't be afraid to use the "m word." As an

example, for grunts it often takes some creative thinking to turn a range you

planned and coordinated into business verbiage but it's more than likely that

you overcame multiple "budgetary, resource, and manpower issues" just to pull

off a single live-fire exercise. It matters. When you are writing your resume

it might be worth the time to tailor a resume for each job you want to apply

for. Don't just use a generic resume. Take the extra time to carefully read

each job description, responsibilities, etc. and then tailor your resume for

that job based on your experiences, deployments, and billets.

2. Do research and find out what companies are

actively recruiting veterans. Most companies have recruiters and H.R.

specialists devoted entirely to veterans. Reach out to them and find out about

recruiting events. For officers MOAA has events that might be worth looking

into. For junior officers membership is free. If you are thinking about a

federal job remember you must use a federal resume. If you aren't familiar with

federal resumes and/or job descriptions reach out to someone. USAJOBS.gov is

still a cumbersome website but it is getting better.

3. Having a clearance is huge. It means a

company spending less money than someone without one and the fact you can get

to work faster is a strong selling point. Get a JPAS letter from your S-2 and

be sure to include your security clearance level and dates on your resume. It is

a must if you want to transition to the contracting or government consulting

world.

4. While you are still in uniform use tuition

assistance to take self-paced Microsoft Office certifications. It would look a

lot better on a resume if you had a certification with Excel and PowerPoint

that just listing you are "proficient." The business world revolves around

Excel and PowerPoint and no matter how many rosters and live-fire confirmation

briefs you made you probably aren't anywhere near as skilled as you think you

are. Completing the certifications while still on active-duty can save you a

lot of money. Also, look into courses for SharePoint, Photoshop, etc.

5. Try and get strong letters of

recommendations from someone who can truly speak to your ability. Your company

commander or battalion commander might not be the best person despite their

rank. Also, if you list someone as a reference please make sure they are aware

of it. Sounds obvious but you would be surprised. Companies do call your

references so make sure anyone you list has your most up-to-date resume,

billet, etc. information handy. [[BREAK]]

6.

Market you ability to learn quickly and adapt, work in a fast-paced

environment, and strong work ethic assuming you have those things. A lot of

companies are willing to hire veterans in entry level positions because of the

aforementioned abilities and capabilities and teach you what they need you to

know. You may have to sell your potential not necessarily what you did in the

past. Even after ten years at war, a lot of people still have no understanding

of the military structure, so be sure to explain your billet and

responsibilities and, relating back to my second point, how they relate to the

job you are applying to.

7. Be humble! As an officer or SNCO you may

have to start in an entry-level position. If you really are as good as you say

you are then your ability will speak for itself and you will do good things and

rise to the top. It might be hard and incredibly frustrating being the junior

guy or girl in a four man team when you were a former company commander or

platoon sergeant but you need to be prepared for that possibility and accepting

of it. Just perform and hopefully you will be awarded accordingly. Also, if

there is any idea or sense of entitlement because of your service then it needs

to be dropped. People can sense it and while your service is something to be

proud but don't let it lead to being condescending. There is a lot of

competition in the job market and you have to prove yourself all over again.

8. Network. This can't be stressed enough. Talk

to former Marines and veterans and find out what worked for them when they

transitioned to the private sector. I would even cold call someone or e-mail

them even if you don't know them personally but you know they are a veteran or

former Marine. Marines are always willing to take care of each other. At least

that was my experience. Employee referrals can go a long way. Reach out to

former commanders that you know are no longer in uniform. A friend of a friend

could mean a job.

9. Be patient. You more than likely won't find

a position right away. Have a financial plan in place in the event that you

cannot find a job. Don't count out the Reserves either. The Marine Corps is

really hurting for infantry officers and SNCOs in the Reserves. Just having the

drill weekend pay check once a month could help ease your financial situation

and buy you some more time. The other great thing about the Reserves is

networking. Talk to your peers if you do transition and find out what they do.

There is a wealth of knowledge, experience, and opportunity in the Reserves.

10.

If you are going to use the GI Bill right away then have a plan of attack. I

can't tell you how many times I asked Marines that were transiting what their

plan was and it was to just "go back to school." Not acceptable. Work with the

school you want to apply to and find out what assistance they have for

veterans. The UNC, California, and Texas schools systems have outstanding

opportunities. There is an article in the New York Times about Columbia's

outreach to veterans. Also, odds are that your SAT/ACT scores are out of

date so start studying now while you are still in uniform and getting a pay

check. Depending on operational tempo do not wait until you EAS to make a plan.

By that point you are way behind schedule. You can get free SAT/ACT study

guides while on active-duty from the learning resource and career centers.

Command permitting, you could even use tuition assistance for an EMT course,

etc. Take SEPS/TAPS early and use the resources provided. Don't take it two

weeks before you EAS. There is a lot of vocational training and resources that

you won't have once you EAS.

The author is a former active duty

Marine infantry officer recently hired by a Fortune 500 consulting firm. He is

now a Reservist. The views of the writer represent the individual and not the

views of the United States Marine Corps of the Department of Defense.

November 14, 2011

A Marine staff sergeant inquires: What's it like out there in the civilian workplace?

Here's a question from a Best Defender that I answered, but

am passing along (with the permission of the sender).

I am a Staff Sergeant with 12 years in the Marine Corps

whose "fun meter" has bottomed out. I have received a B.S. in Finance

and am working on a HR certification. I read your post from November 2nd about

a former Captain having difficulty with veteran hires and it concerned me.

I have spent the last few years preparing myself to separate from active

service and am excited about a future working for a company where I can truly

feel like my efforts are helping the company succeed. Is the idea that I can

leave the military and become an all-star for a company a fantasy in today's

business climate?

My response was that it's tough out there, but that he might

have luck with a company with a reputation for hiring Marines. Suggestions?

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers