Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 219

November 9, 2011

19 true things generals can't say in public about the Afghan war: A helpful primer

As a public service, Best

Defense is offering this primer for generals on their way to Afghanistan.

Here is a list of 19 things that many insiders and veterans

of Afghanistan agree to be true about the war there, but that generals

can't say in

public. So, general, read this now and believe it later-but keep your lip

zipped. Maybe even keep a printout in your wallet and review before interviews.

My list of things to remember I can't say

Pakistan

is now an enemy of the United States.

We

don't know why we are here, what we are fighting for, or how to know if we are

winning.

The

strategy is to fight, talk, and build. But we're withdrawing the fighters, the

Taliban won't talk, and the builders are corrupt.

Karzai's

family is especially corrupt.

We

want President Karzai gone but we don't have a Pushtun successor handy.

But

the problem isn't corruption, it is which corrupt people are getting the

dollars. We have to help corruption be more fair.

Another

thing we'll never stop here is the drug traffic, so the counternarcotics

mission is probably a waste of time and resources that just alienates a swath

of Afghans.

Making

this a NATO mission hurt, not helped. Most NATO countries are just going

through the motions in Afghanistan as the price necessary to keep the US in

Europe

Yes,

the exit deadline is killing us.

Even

if you got a deal with the Taliban, it wouldn't end the fighting.

The

Taliban may be willing to fight forever. We are not.

Yes,

we are funding the Taliban, but hey, there's no way to stop it, because the

truck companies bringing goods from Pakistan and up the highway across Afghanistan

have to pay off the Taliban. So yeah, your tax dollars are helping Mullah Omar

and his buddies. Welcome to the neighborhood.

Even

non-Taliban Afghans don't much like us.

Afghans

didn't get the memo about all our successes, so they are positioning themselves

for the post-American civil war .

And

they're not the only ones getting ready. The future of Afghanistan is probably

evolving up north now as the Indians, Russians and Pakistanis jockey with old

Northern Alliance types. Interestingly, we're paying more and getting less than

any other player.

Speaking

of positioning for the post-American civil war, why would the Pakistanis sell

out their best proxy shock troops now?

The

ANA and ANP could break the day after we leave the country.

We

are ignoring the advisory effort and fighting the "big war" with

American troops, just as we did in Vietnam. And the U.S. military won't act any

differently until and work with the Afghan forces seriously until when American

politicians significantly draw down U.S. forces in country-when it may be too

damn late.

The

situation American faces in Afghanistan is similar to the one it faced in

Vietnam during the Nixon presidency: A desire a leave and turn over the war to

our local allies, combined with the realization that our allies may still lose,

and the loss will be viewed as a U.S. defeat anyway.

Thanks to several people who contributed to

this, from California to Kunar and back to DC, and whose names must not be

mentioned! You know who you are. The rest of you, look at the guy sitting to

your right.

Gray and strategy (IV): The airpower view of the world is essentially nonsense

It is rare to see a careful strategic writer denounce a

point of view so absolutely: "What is the strategic worldview of the air

person? In effect, he or she sees the world as akin to a dartboard ... Needless to say, perhaps, such a view is nonsense. But, it has always lurked

more or less explicitly in the belief structure of true believers in victory

through air power." (P. 113)

Meanwhile, the Air Force practiced

bombing Santa Claus.

Civil-military relations and OWS: Maybe Metzenbaum was right about John Glenn

By Jim Gourley

Best Defense directorate

of civil-military relations

Several recent

posts on this blog have dealt with the financial exigencies of the defense

establishment, the operations

and resourcing

of its component services, success of its attendant

contractors and the consequences

to its individual members in the context of America's worsening economic

milieu. Adjacent to this discussion is the emergent trend of greater numbers of

military veterans joining the "Occupy Wall Street" movement. In the background

of these complimentary events stand troubling statistics. Military veterans are

currently 2.6 percent more likely to be unemployed than civilians. As discussed by the

Joint Chiefs of Staff before Congress last

week, if budget cuts move forward as planned, more than 57,000 active duty

personnel will be added to the ranks of the jobless. Despite recent action by

the Obama administration to catalyze hiring of veterans, there

is evidence that the private sector is less interested than ever in hiring

people with military experience. And that favorite parachute of separated

military members, civilian government service, is too tattered to

provide any guarantee of safety. Even that pot of gold at the end of the

rainbow, the twenty-year retirement payout, has been drawn precariously close

to the chopping block.

So it is with great

shock that I observe the proliferation of so much anti-OWS media among military

members and veterans, and the especially vitriolic tone expressed in their

discourse. I have listened to many friends and acquaintances deride the

protestors as college punks, effete snobs, and even "commie liberals"

who are simply whining when they should be getting to work and actually doing

something with their lives -- like military members. Some have even gone so far

to point out that those protestors dissatisfied with their "safe cubicle

jobs" should join the overstretched and undermanned military; a puzzling

recommendation in light of the aforementioned looming personnel cuts. When I

have mentioned the involvement of veterans in the OWS movement to these

acquaintances, they have responded by devaluing the service of these veterans

(as has

been attempted even on this blog, regarding Scott

Olsen) and claiming that the groups to which they belong and political

causes they advocate are radical, unworthy, or otherwise invalid. This

inconsistency in recognizing common ground with fellow veterans, the apparent

disregard for just how little security exists in military service, and the

extreme degree of self-righteousness demonstrated by military members in the

conduct of this dialogue has led me to conclude that there exists a definitive

financial metric in the often discussed gap between military and civilian

society.

To put it

succinctly, Howard Metzenbaum was right when he questioned John Glenn's work

history.

Metzenbaum ran

against Glenn in the 1974 campaign for one of Ohio's Senate seats. During one

of their debates, Glenn issued his now famous "Gold Star Mother"

speech, in which he challenged Metzenbaum to tell injured service members, the

families of dead astronauts and mothers of fallen troops that military members

had never "held a real job." However, the voting public missed a

cleverly subtle misquote by Glenn amidst his soaring oratory filled with the

language of freedom and patriotism. What Metzenbaum actually said was that

Glenn had never "made a payroll." He believed that, for all Glenn's

courage and dignified service, he was not in touch with the plight of the

average working class American citizen. That Metzenbaum lost the election

largely on the basis of this debate is especially ironic in the context of his

long record of fighting for workers' rights.

To be sure, the

military member endures great personal risk and hardship. There is no disputing

that too many are called upon to make the ultimate sacrifice, and the

sacrifices of countless others are priceless. But the hard truth of the matter

is that our entire country faces extraordinary economic hardship, and service

members and veterans must be included in the discussion of dollars and sense. To

that end, a

recent report by the Congressional Budget Office finds that military

members are paid considerably well -- and in some cases better -- compared to

their civilian counterparts. Even the authors of the paper admit that it is

hard to compare the value of military members' service against civilians,

though, due to separation from family, harsh working conditions, and health

consequences. Service in time of war is the flag around which derisive military

members rally. They respond to the OWS movement's "I am the 99 percent"

motto by citing that only one percent of the American population "makes

the sacrifice to defend freedom." Tired recitations of Orwell and Father Dennis

O'Brien seem to follow as surely and rhythmically as Jill came tumbling after. But

if the combat tour is the hill this argument stands on, it breaks its crown

before it even starts. The club of hallowed warriors whose financial security

should remain indemnified is much more exclusive than 1 percent. Since the Korean War,

fewer

than 35 percent of all active duty service members have ever been deployed outside

the United States. Less than

half of all uniformed service members deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq

between 2001 and 2004.

This is to say

nothing of how military employment compares to circumstances in the civilian

market, and this is where Metzenbaum's observations become more relevant. While

the combat troop must contend with enemy fire and IEDs, they have never had to

worry about health insurance. Only recently were they given a scare as to

whether their next paycheck would hit on time. The emotionally overwrought news

and social media campaign about the dire straits our troops would be left in if

the "government failed them, even as they fight for us" ought to be

illuminating, but the military community seems to have failed to hold the

mirror up to face facts. They have lost perspective of their place in the world

amidst the constant drumbeat of patriotism, long march of military discounts

and society's constant refrain to "support our troops." On the

financial level, the truth is that they

live on no different terms than the rest of Americans. In the civilian

world, they stand a higher chance to

live on much worse terms.

Military members

are quick to grouse these days that support for the wars has dried up since the

national dialogue has turned to Wall Street. It's the "we're already being

forgotten" tune. But in actuality it's the military that's forgetting. For

nearly a decade, the armed forces have enjoyed the support of American

solidarity on a near-unprecedented level. There can be no doubt that many of

the people attending 'Occupy' movements around the country at one time or

another found a way to express their support of service members. It is certain

that, not so long ago, the veterans in the crowd stood next to those who remain

in uniform. Whether military members support the movement or its beliefs is a

matter of personal choice. But the viciousness demonstrated in the commentary

of many military members is contradictory to the obligations of basic human

compassion. The front lines of combat are difficult and dangerous. Honor and

respect is owed to those who serve there. But there is also honor in every

other kind of honest labor. It is unconscionable for one to demand special

tribute for service to country by fighting on the front line, and then deny a

person's right to fight against indignity while working

on the checkout line. Military members have had to make difficult choices

and regrettable sacrifices. But the majority of them have never had to make a

payroll. They should not take for granted the plight of those that do.

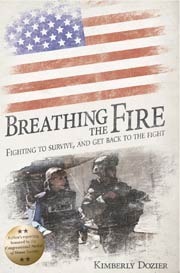

Kim Dozier's book about being blown up

This

is the best book I've read about being blown up in Iraq, nearly dying, and

recovering. Kim, one of the more courageous people I've ever met, is donating

all profits to charities for wounded soldiers. So what are you waiting for? Click here!

November 8, 2011

A few thoughts on that CNAS study about how to reduce military and vet suicides

By Stacy Bare

Best Defense guest commenter

The Center for a New American

Security hosted a policy briefing recently titled, "Losing the Battle:

The Challenge of Military Suicide." I was excited to see a room full of

200+ people discussing the challenges around preventing military and veteran

suicides. CNAS is a well-respected think tank and also published a policy brief

of the same title on the subject. What would we learn? How would the national

dialogue around military and veteran suicide be impacted? Would we find

innovative new ideas for possible solutions?

Here's the catch though, the discussion was not, in my mind, so much about the

concern for the unnecessary death of hundreds and thousands of men and women,

but to ensure that men and women would keep enlisted. To quote from page one of

the report, which can be found here,

"If military service becomes associated with suicide, will it be possible to

recruit bright and promising young men and women at current rates?...Can the

all-volunteer force be viable if veterans come to be seen as broken

individuals?"

So what: If too many of us commit suicide we'll be forced to have a

conscription military?

And now to the answers:

What would we learn?

Not a lot of new information if you've been following the national dialogue,

but I'll recap it here:

Last year 295 members of all services committed suicide

The VA's best guess is that 18 veterans a day are committing suicide

The VA's best guess comes from a 2009 report, meaning it was using 2008 data

or pre-economic crash; it would be a safe assumption to make that we are losing

more than 18 veterans a day to suicide

The DoD is investigating and working on a number of medical studies relating

to brain trauma and suicide

The Army has instituted a 15 minute on-line survey returning combat soldiers

are supposed to take that will help identify

50 percent of all military suicide victims were seeking mental health at the time of

death

How would the national dialogue be impacted? [[BREAK]]

I left the briefing frustrated and angry, because I do not think the national

dialogue will be impacted at all by the policy briefing and conversation that

was had yesterday. The framework around the discussion is entirely wrong and

the CNAS briefing only helped to reinforce the false assumptions of the debate,

and that is, that the onus of reintegration and mental health falls squarely on

the shoulders of the Department of Defense (DoD) and Veterans Administration

(VA).

Until we shift the paradigm to ensure the burden of reintegration and mental

health is shared at least equally by, if not more so, by the community at

large, I do not see a likely decrease in the numbers of veteran or active duty

suicides.

Community participation and coordination of community and veteran service

organizations to allow for more community involvement and a concentrated effort

on understanding and better meeting veteran and military service members needs

will help 'win the battle'.

I appreciate the work the panelists are doing and what they're trying to do. I

certainly do not think funding should be cut from the DoD or VA. In some

places, it needs to be expanded and communities need to be let in to take care

of their troops, their veterans, and their military families.

As a society, we've asked for men and women to volunteer to become trained

killers. Men and women who are ready to execute the violent, deadly, and often

messy tasks required of our existing national defense and foreign policy goals.

We've gone, we've done our duty, we're doing the best we can to take care of

our own, but its time for communities to step up and do their duty in return

and to have this be recognized as the solution at the highest levels. Many

communities and community organizations are stepping up, but our policy makers

and national thinkers are still missing the boat.

What innovative ideas and recommendations did we hear?

You can read the policy brief here

and make your own mind up, but I did not hear anything that I thought would

work. No game changers in here folks, just some common sense ideas that you may

be shocked were not already implemented.

Here are a few ideas that I think might be effective at curbing veteran suicide

and that could really impact the national dialogue:

Stop going to war

Incentivize healing and do not take veteran benefits away because they get

better

Streamline the paperwork process for getting help in the VA

Encourage community organizations to coordinate veteran and military services

Honor military service through participating in the freedoms and privileges

we helped to defend, such as voting, using public lands

Treat veterans like people, not monsters and give us a fair playing field

Recognize your involvement in this war as a citizen or resident of our

country

Learn about the military, its history, its rank structure, its branches, so

you can speak intelligently and with the same vocabulary as service members

Do not equate playing high school football or other sports with the camaraderie

of military service

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed someone

We can stop 18 veteran suicides a day, we can beat this problem, but we all

need to participate, not just the military. On Nov. 8, honor a veteran,

vote.

Stacy Bare served as a

captain in the U.S. Army from 2000-2004 and again from 2006-2007. He served as

the Counter Terrorism Team Chief in Sarajevo, Bosnia, in 2003-04 and as a Civil

Affairs Team Chief in Baghdad, Iraq, from 2006-07. He is now the Military

Families and Veterans Representative for the Sierra Club. Stacy is 6'8"/260+

and might have played for the All Blacks

but for his love of veterans and rock climbing.

Barno: Generals who can't handle dealing with the media aren't very good generals

By Lt. Gen. David Barno,

USA (Ret.)

Best Defense office of flag officer affairs

The recent firing of Maj.

Gen. Fuller by ISAF commander Gen. John Allen once again has thrust the

interaction between the media and our senior military leaders into the public

sphere. For a General Officer (not a lieutenant)in today's world, effectively

dealing with the media and conducting all manner of operations in a media

intense environment is a core competency. If GOs are unable to navigate that

environment today, they simply should not be GOs. The trend toward "press

avoidance" by more and more generals as an escape route reflects a GO

population that is out of its depth in understanding and dealing with the

Fourth Estate -- and, arguably, therefore also in communicating to the American

people. Avoiding the press is in many ways an abdication of commanders'

fundamental responsibility to tell the story of their command or mission to the

our citizenry and to our lawmakers, almost all of whom learn these things only

through the news.

Understanding the global media environment and maintaining the daily

situational awareness of what's going on around them is a fundamental of

strategic leadership in 2011. GOs who are less than 3-dimensional leaders will

have difficulty with this -- it would be interesting to dissect MG Fuller's

background to see if anything in his unusual rise through acquisition ranks to

become the deputy US General training Afghans ever exposed him to anything 3-dimensional

as opposed to 1-D or 2-D largely job-focused tasks.

It is also worth reminding generals of

an obvious point: Even When you are in the depths of an interview, you always

have the opportunity to say nothing! Not answering a question designed to

elicit a "newsworthy" remark is perfectly acceptable - most

especially when you are asked to opine on something that, even though you may

have strong personal feelings, has little or nothing to do with either your job

or the ostensible purpose of the interview. Not answering baited questions is a

level 101 skill - and reflects a smart choice and one much different than

simply parroting command talking points or being "shaped" by a

zealous PAO minder.

The bottom line is that Generals have

to have their wits about them and see where they and their interactions with

media fit in the macro environment - that messy collage of national politics,

ambitious reporters, newsmaking goals, U.S. government and host nation

sensitivities, and the enemy's media game plan. If you can't fit all those

pieces together and operate in that environment, first, you shouldn't try and second,

you probably shouldn't be a general officer in the complex and very public

world of 2011.

IMHO, this is really not all that

stunningly hard to figure out and be ready for - and it's absolutely part of

your job these days as a guy or gal wearing stars on your shoulders.

Inskeep's excellent book-length profile of Karachi, the key to Pakistan: A review

By Ahmed Humayun

Best Defense guest reviewer

America's decade-long war in South Asia

has prompted a spate of books that purport to explain how Pakistan really

works. Though everyone agrees that insurgent-infested and nuclear-armed

Pakistan is tremendously important to U.S. interests, few have been able to

unravel the country's byzantine complexity. In the excellent Instant

City: Life and Death in Karachi,

Steve Inskeep sidesteps the machinations of Pakistan's national politics, the

grinding geopolitical competition in Afghanistan, and the apocalyptic scenarios

of terrorists seizing nuclear weapons, and focuses instead on scrupulously

narrating the everyday stories of the beleaguered citizens who inhabit Pakistan's

most important city. This ostensibly narrow approach ends up illuminating a

vast landscape, showing how decaying institutions have constrained Pakistani

aspirations in tragic and tortuous ways.

According to Inskeep, an "instant

city" is characterized by above average population growth relative to the

rest of the country, often due to mass migration induced by severe political

and economic unrest. Pakistan's partition from India in 1947 produced millions

of desperate refugees on both sides of the bloody border; as a result, Karachi's

population doubled overnight. Pakistan's largest city and a financial and

industrial hub, Karachi still lures migrants in search of economic

opportunities from all across the country. The unremitting influx has

overwhelmed an inadequately resourced government's ability to provide basic

services. The yawning gap between what people need and what the state can

deliver, exacerbated by deep ethnic and sectarian cleavages, has spawned crime

and corruption and violence. Karachi is a sprawling urban mess that cannot be cleaned

up by a municipal authority which is hapless when it is not perfidious.

Nonetheless, desperate people keep

streaming in and the city totters forward. Inskeep is best when delineating the

tactics Karachites use to forge ahead in the face of improbable odds. The katchi

abadis -- so-called 'temporary settlements' comprised of shacks made of mud

and timber -- are technically illegal because they are created by people simply

squatting on vacant land; in reality they house as many as half of the city's

population. Bereft of amenities such as water and energy, residents devise expedient

workarounds -- for example, by planting hooks on main electrical lines,

siphoning off power, and bribing the police to look the other way. Over time,

the process of illegal settlement has become regularized: profiteering land

developers -- who include the local government, political parties, and the

police -- have gained control over vast swathes of real estate which they rent

out to individual residents and communities. As Karachi's titular government

flails, an alternative form of government -- predatory but characterized by

certain informal rules -- has sprung up. [[BREAK]]

A few courageous souls fight the social

consequences of a crumbling state. A wealthy philanthropist couple is devoted

to providing affordable and healthy housing for the poor. An octogenarian

humanitarian annually collects millions of dollars in contributions that funds

a vast array of social services -- even as he himself does not own a house,

living in sparsely furnished rooms at his work headquarters. A doctor in charge

of the emergency department at Jinnah Hospital attends to the victims of a

sectarian suicide bombing even after the hospital itself is attacked just a few

hours later.

For those steeped in Karachi's lore,

such stories are unsurprising. Unfortunately, the rewards for heroism in such a

city are sparse. Life in urban South Asia rarely resembles Oscar-baiting

fantasies like the Academy Award winning Slumdog Millionaire, and

Inskeep is not in the business of selling uplifting bromides to his readers.

Again and again, Karachites striving to create a better life for themselves and

for their communities are thwarted by forces much larger than themselves. In

one of the book's most haunting stories, a social activist named Nisar Baloch

tries to save a public park in his neighborhood from unlawful encroachment. The

day after he denounces the land grab in a press conference he is murdered. Who

killed Baloch? No one can tell Inskeep for sure, but his dogged investigation

locates clues scattered like crumbs. The local government is dominated by the

Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) - a powerful provincial political party whose

votes are critical to the fragile coalition government steered by the ruling

Pakistan People's Party (PPP). The MQM was doling out the park land to its

constituency, the ethnic Mohajirs. Baloch belonged to a different ethnic group

that has tense relations with the Mohajirs in that neighborhood. Although

Baloch was a dedicated member of the PPP and his death led to spontaneous riots

and protests, his party stayed silent and the encroachment continued.

Instant City

pivots on Dec. 28, 2009 -- a day Inskeep says "almost everyone in Karachi

remembered" -- when extremists bombed a religious procession on Ashura, the

annual Shiite day of mourning. Inskeep describes the events of that day and the

lives that intersected with it, using their stories as a window into the

tensions roiling Karachi. This narrative strategy succeeds in riveting the

reader's attention before deftly segueing to broader geographic, political, and

historical factors that influence the city.

Yet the structure of Inskeep's tale has

some flaws. Anti-Shiite terrorism is a longstanding part of Karachi's history

and deserves to be highlighted, but the city is too vast to be filtered through

the prism of one day's events. Inevitably several of the book's chapters,

though well-crafted vignettes in their own right, are disconnected from each

other. Furthermore, although Inskeep provides an intriguing definition of what

constitutes an "instant city," his discussion of the concept is

underdeveloped. His preferred method is to compare Karachi to other "instant

cities" -- for example, he suggests that post-partition migration to

Karachi fueled ethnic tensions similar to Chicago in the 1830s -- but these

fleeting analogies are sometimes superficial.

Instant City's

real strength lies in conveying powerful stories through cinematic prose. At

his best, Inskeep conjures up the visceral experience of life in Karachi with

all its incongruities, its brooding intensity, and yes, its flashes of vitality

and fun. Reading the book I often felt transported back to the early 1990s when

I attended middle school in Karachi. When school was shut down -- due to

strikes or municipal crises or any number of other reasons I was oblivious to

then -- we would illegally play cricket on the roads, skirting the honking cars

that crossed red stoplights and thundered across our makeshift pitches. We

survived and even enjoyed ourselves along the way. Instant City is full

of keenly observed insights about a battered and bloodied city that still hasn't

quite given up.

Ahmed Humayun is

a fellow at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding.

November 7, 2011

The future of the force: Better think twice before cutting lots of heavy ground units

Here is an excerpt

from an e-book,

The Wounded Giant: America's Armed

Forces in an Age of Austerity, to

be published

next week by Penguin Press.

By Michael O'Hanlon

Best Defense guest

commentator

During the Vietnam War,

the United States Army's active-duty forces were almost a million and a half

soldiers strong. In World War II, the number had approached six million (not

counting the Army Air Force or other services). Under Ronald Reagan, the figure

was more like 800,000. After reducing that strength when the Cold War ended to

less than half a million, and after considering Donald Rumsfeld's ideas in

early 2001 to cut even more, the nation built up its standing Army by almost

100,000 troops over the last decade, while modestly increasing the size of the

Marine Corps from about 170,000 to 200,000 active-duty Marines as well. We are

now on a downward slope again. But how low can we go?

It is easy to see the

pros and cons of deeper cutbacks. On the favorable side, we are a nation tired

of war, and especially tired of long counterinsurgency missions in distant

Asian lands -- not for the first time in our history. In addition, we have

oceans to protect us from most potential adversaries, and high-technology

weapons to try to keep the peace without putting U.S. troops on the ground in

distant lands. On the other hand, in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade,

we have relearned the lesson that if you want to enhance the stability of a

faraway land, you cannot do it with the "shock and awe" of air and missile

strikes alone. In addition, if you go in too small, you may only worsen the

situation and have to salvage it with larger forces later. Moreover, the size

of armies needed to help stabilize such places is partly a function of the size

of their populations, not just the quality of our technology or our troops on a

person-by-person basis. In a world with more than six billion people, hundreds

of millions of whom are still living in turbulent places that could threaten

U.S. interests, it is not clear that the American Army can keep getting

smaller.

And even if we try simply

to avoid manpower-intensive war in the future, we may just fail. We have tried

that approach before, deciding that as a nation we were simply done with

certain forms of combat. But then we have usually wound up being forced by the

course of history to re-learn old lessons and re-create old capabilities when

our crystal balls proved to be cloudy, and our predictions about the nature of

future combat proved wrong. The stakes involved in faraway lands in the age of

transnational terrorism and nuclear weapons are too high for us to blithely

assume that we've seen the last of complex ground missions in distant lands

just because we don't happen to like them. [[BREAK]]

The U.S. military today is indeed the second largest

military in the world, after China's. But it is only modestly larger than those

of North Korea, India, and Russia. The size of its active-duty Army also only

modestly surpasses that of South Korea and Turkey, among others. So as we begin

the debate about its future size, we are not exactly beginning with a huge

force as a starting point.

Nevertheless, the U.S.

military probably can become smaller as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wind

down. We should not rush into this, and we should not adopt the attitude some

advocate that America's main overseas capabilities be reduced principally to

Air Force and Navy capabilities. The latter services are formidable and

essential. But "standoff" warfare featuring long-range strikes from planes and

ships cannot address many of the world's key security challenges today -- and

possible scenarios in places like Korea and South Asia, discussed further

below, that could in fact imperil American security. In the 1990s, advocates of

military revolution often argued for such an approach to war, but the

subsequent decade proved that for all our progress in sensors and munitions and

other military capabilities, we still need forces on the ground to deal with

complex insurgencies and other threats.

An emphasis on standoff

warfare is sometimes also described as a strategy of "offshore balancing" by

which the distant United States steps in with limited amounts of power to shape

overseas events, particularly in Eurasia, rather than getting involved directly

with its own soldiers and Marines. But offshore balancing is too clever by

half. In fact, overseas developments are not so easily nudged in favorable

directions; proponents of this approach actually overstate American power. It

also suggests a lack of real American commitment. That can embolden adversaries

and worry friends to the point where, among other things, they may feel obliged

to build up their own nuclear arsenals -- as the likes of South Korea, Japan,

Taiwan, Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia might well do absent strong security

ties with America.

All that said, we will

have to streamline in the years ahead. This is not really for any lack of

manpower to people a larger Army and Marine Corps. We have nearly five million

young people reaching eighteen every year, and need to recruit only about

200,000 at present for the current military. Although many of the remaining 4.8

million do not qualify for today's force due to their lack of fitness,

educational attainment, or other characteristics, ways could be found to make

more of them eligible -- such as my friend Marshall Rose's idea of premilitary

fitness camps that could whip out-of-shape young men and women into shape

with incentives for positive completion. At present, however, and certainly for

as long as the U.S. economy remains weak, availability of manpower will not be

our limiting factor. Rather, it is that the expense of having people in uniform

has become so great that we must not have more troopers than we need.

As such, once the wars

wind down, we should reverse the recent increases in the active forces of the

U.S. Army and Marine Corps and return to Clinton and early Bush levels. That

would mean roughly 15 percent cuts, relative to current combat force structure

-- roughly twice the cut currently planned by the services. There was in fact a

reasonable amount of bipartisan consensus on those earlier force levels, with

defense secretaries Aspin, Perry, Cohen, and Rumsfeld all supporting them over

a ten-year period. These reductions in ground forces would not quite achieve 15

percent reductions in costs, as certain nonlinearities exist. New weapons must

still be developed regardless of how many will be purchased; weapons unit costs

tend to go up when fewer are purchased; some support activities like

intelligence do not decline automatically when force structure is cut. But

savings would be 10 to 12 percent in the ground forces, or $15 billion to $18

billion in annual spending. Commensurately, Air Force tactical combat forces

might be cut 10 percent.

To give a sense of the

respective facts and figures, today's U.S. Army has about 550,000 active-duty

soldiers. In addition, as of early 2011 data, another 110,000 reservists had

been temporarily activated -- nearly 80,000 from the National Guard and just

over 30,000 from the Army Reserve. The U.S. Marine Corps is about 200,000

strong, with another 5,000 Marine reservists temporarily activated. By

contrast, the active Army of 2000 was 472,000 strong and the Marine Corps

numbered 170,000. Excluding activated reservists, therefore, making 15 percent

personnel cuts would reduce current levels approximately to those of a decade

ago.

Today's Army likes to

organize its forces and measure its strength more in terms of brigades than the

old standard of divisions; there are usually now four brigades to a division,

and the former have been turned into units that are independently deployable

and operable in the field. Today's ground forces include forty-five brigade

combat teams in the active Army as well as twenty-eight in the National Guard.

The Army also has thirteen combat aviation brigades in the active force and

eight in the reserve component. The Marines, organized somewhat differently and

using different terminology to describe their main formations, have eleven

infantry regiments as well as four artillery regiments. Roughly speaking, a

Marine Corps regiment is comparable in size and capability to an Army brigade.

Throughout the 1990s,

U.S. ground forces were sized and shaped primarily to maintain a two-war

capability. The wars were assumed to begin in fairly rapid succession (though

not exactly simultaneously), and then overlap, lasting several months to

perhaps a year or two. Three separate administrations -- Bush 41, Clinton 42,

and Bush 43, and a total of five defense secretaries -- Cheney, Aspin, Perry,

Cohen, Rumsfeld -- endorsed some variant of it. They formalized the logic in

the first Bush administration's 1992 "Base Force" concept, the Clinton

administration's 1993 "Bottom-Up Review" followed four years later by the first

Quadrennial Defense Review, and then Secretary Rumsfeld's own 2001 QDR. These

reviews all gave considerable attention to both Iraq and North Korea as

plausible adversaries. More generally, though, they postulated that the United

States could not predict all future enemies or conflicts, and that there was a

strong deterrent logic in being able to handle more than one problem at a time.

Otherwise, if engaged in a single war in one place, the United States could be

vulnerable to opportunistic adversaries elsewhere. With Saddam Hussein gone,

this deterrent logic can be adjusted, a point to which we return below.

In these debates in the

dozen years following the Cold War and Desert Storm, most considered actual

combat in two places at once unlikely. Few predicted prolonged wars in two

places at once. Yet we got exactly that in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last

ten years. Of course, many disagreed with the decision to go to war in Iraq in

particular. But the basic fact that conflict is unpredictable -- that, to quote

the old aphorism, "You may not have an interest in war but war may have an

interest in you" -- endures.

The Obama administration

appears to agree; as its 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review Report states,

after successfully concluding current wars, "In the mid- to long term, U.S.

military forces must plan and prepare to prevail in a broad range of operations

that may occur in multiple theaters in overlapping time frames. This includes

maintaining the ability to prevail against two capable nation-state aggressors.

. . . "The Obama QDR is actually somewhat more demanding than the military

requirements that guided American planners between 1991 and 2001. It adds a

stabilization mission and smaller operations on top of the two-war requirement,

though it may be overestimating the capacities of its force structure in doing

so.

In my judgment, though, a

two-land-war capability is no longer appropriate for the age of austerity. The

"one war plus several missions" framework proposed here for sizing combat

forces -- "one plus two" for short, if the two is understood as two relatively

significant efforts -- is designed to be a prudent but still modest way to ensure

this type of American global role. It is prudent because it provides some

additional capability if and when the nation again engages in a major conflict,

and because it provides a bit of a combat cushion should that war go less well

than initially hoped. It is modest, verging on minimalist, however, because it

assumes only one such conflict at a time (despite the experience of the last

decade) and because it does not envision major ground wars against the world's

major overseas powers on their territories.

More specifically, if

there ever was conflict pitting the United States against China or Iran, for

example, it is reasonable to assume that the fighting would be in maritime and

littoral regions. That is because the most plausible threat that China would

pose is to Taiwan, or perhaps to neighboring states over disputed sea and

seabed resources, and because the most plausible crisis involving Iran would

relate either to its nuclear program or to its machinations in and about the

Persian Gulf waterways. It is reasonable for the United States to have the

capability for just one ground war at a time as long as it can respond in other

ways to other possibly simultaneous and overlapping challenges abroad.

Having such a single

major ground-war war capability is somewhat risky, underscoring the risks of

even deeper defense cuts than I am outlining here. But it is hardly radical or

unprecedented. During the Cold War, American defense posture varied between

periods of major ambition -- as with the "2½ war" framework of the 1960s that

envisioned simultaneous conflicts against the Soviet Union (probably in

Europe), China in East Asia, and some smaller foe elsewhere -- and somewhat

more realistic approaches, as under Nixon, which dropped the requirement to 1½

wars. Nixon's "1 war" would have been conflict in Europe against the Warsaw

Pact, a threat that is now gone. His regional war capability, or his "½ war"

posture, was therefore similar to what I am proposing here. Nor does this

proposal lead to a dramatically smaller ground force. Having the capacity to

wage one major regional war with some added degree of insurance should things

go wrong, while sustaining two to three protracted if smaller deployments, is

only modestly less demanding than fighting two regional wars at once.

Unfortunately, today's world does not allow a prudent decision to go to an even

less demanding strategic construct or an even smaller force.

This one-war response

capability needs to be responsive and highly effective to compensate for its

modest size. That fact has implications in areas like strategic transport,

discussed further in the next chapter. It also has implications for the

National Guard and Reserves. They remain indispensable parts of the total

force. They have done well in Iraq and Afghanistan, and merit substantial

support in the years ahead -- better than they have often received in our

nation's past. But they are not able to carry out prompt deployments to crises

or conflicts the way that current American security commitments and current

deterrence strategy require. As such, we should not move to a "citizens' army"

that depends primarily on reservists for the nation's defense.

Translating this new

strategy -- one war, plus several smaller missions -- into force planning

should allow for roughly 15 percent cutbacks. Army active-duty brigade combat

teams might number about thirty-eight, with the National Guard adding

twenty-four more. Combat aviation units might decline to eleven and seven

brigades in the active and National Guard forces, respectively. The Marines

would give up perhaps two units, resulting in ten infantry and three artillery

regiments respectively in their active forces, while keeping their three

divisions and three associated Marine Expeditionary Forces. This force would be

enough to sustain about twenty combat brigade teams overseas indefinitely, and

to surge twenty-five to thirty if need be. If the United States found itself in

a major operation, it could and should begin to reverse these cuts immediately,

building up larger active ground forces as a hedge against the possibility that

the new operation (or additional ones) could prove longer or harder than first

anticipated. But that would take some time, roughly two to five years to make a

meaningful difference, and as such the peacetime cuts should not go too far.

The above deployment math

is based on the principle that active forces should have roughly twice as much

time at home as on deployment and that reservists should have five times as

much time at home as abroad -- even in times of war. That would be enough for

the main invasion phase of the kinds of wars assumed throughout 1990s defense

planning and the invasion, occupation, and stabilization of Iraq actually

carried out in 2003; force packages ranging from fifteen to twenty brigades

were generally assumed or used for these missions. So the smaller force could

sustain an Iraq-like mission for months or even years while also doing smaller

tasks elsewhere.

This capacity falls short

of the twenty-two brigades deployed in 2007-8 just to Iraq and Afghanistan, to

say nothing of Kosovo or Korea, where additional brigade-sized forces were also

present in that time period. If multiple long crises or conflicts occurred in

the future, we would have to ratchet force strength back up. Thankfully, the

Army and Marine Corps of the last ten years proved they can do this. They added

that 15 percent in new capability within about half a decade without any

reduction in the excellence of individual units.

Somewhat greater savings

-- $5 billion to $8 billion more per year -- could be realized if the same

capability was retained but more of it was located within the Army National

Guard. Rather than downsize from forty-five active brigade combat teams and

twenty-eight Guard teams to respective figures of thirty-eight and twenty-four,

as recommended, one might reduce the active brigades down to just twenty-eight

in number for example. The active-duty Army would wind up totaling fewer than

400,000 soldiers with this proposal. The overall U.S. military might compensate

by adding not just ten but twenty National Guard brigade combat teams to its

force structure, for a total of forty-four. That would keep unchanged the total

Army ability to carry out a long-term deployment at acceptable deployment rates

for reservists. (In other words, it would add enough additional Guard brigades

that their numbers would compensate for the fact that they couldn't be used as

often as active units.) This would amount to a major shift in the character of

the American Army and would place huge faith in the reserve component.

Arguably, the reserve component has proven in recent years that it is up to the

task. With twenty-eight active brigades, the Army would still have enough

capability to conduct two or three missions while having perhaps fifteen to

twenty active-duty brigades ready for quick deployment to a war. However, if a

war did begin, the Army would need to move very fast to mobilize a dozen or

more Guard brigades to allow them the time needed to train properly so that they

could replace the initial response force within a year or so if the operation

was not quickly concluded. I am uncomfortable with this degree of reliance on

the reserves given the time pressures involved, but it is worth acknowledging

that the option does exist.

Some might question

whether we even still need a one-war capability. Alas, it is not hard to

imagine plausible scenarios. Even if each specific case is unlikely, a number

of scenarios cannot be ruled out. What if insurgency in Pakistan began to threaten

that country's nuclear arsenal, and the Pakistani army concluded that it needed

our help in stabilizing their country? Far-fetched at present, to be sure -- but

so was the idea of war in Afghanistan if you had asked almost any American

strategist in 1995 or 2000. Or perhaps, after another Indo-Pakistani war that

reached the nuclear threshold, the international community might be asked to

lead a stabilization and trustee mission in Kashmir following a ceasefire -- not

an appealing prospect to anyone at present, but hard to rule out if a nuclear

exchange put the subcontinent on the brink of complete disaster. What if Yemen's

turmoil allowed al-Qaeda to set up a major sanctuary there like it did in

Afghanistan fifteen years ago? What if North Korea began to implode and both

South Korea and the United States felt the need to restore order before the

former's estimated nuclear arsenal of perhaps eight bombs wound up in the wrong

hands?

Consider the Korea case

in more detail. This would not necessarily be a classic war; it could result,

for example, from an internal coup or schism within North Korea that

destabilized that country and put the security of its nuclear weapons at risk.

It could result somewhat inadvertently, from an exchange of gunfire on land or

sea that escalated into North Korean long-range artillery and missile attacks

on South Korea's close-by capital of Seoul. If the North went down this path,

something that its brazen 2010 sinking of the South Korean navy ship Cheonan

and subsequent attacks on a remote South Korean island that together killed

about fifty South Koreans suggest not to be impossible, war might occur out of

an escalatory dynamic the two sides lost control over. Certainly the way in

which North Korea remains a hypermilitarized state, devoting by far the largest

fraction of its national wealth to its military of any country on Earth, while

accepting that many of its people wallow in poverty or even starve, should make

one worry somewhat. Perhaps Pyongyang might be inclined to try to use that

military -- in an attempt at brinkmanship or extortion that was foolish to be

sure, but that could still prove quite dangerous. It is largely because of such

possibilities that the United States should not abandon its South Korean ally,

even though that nation is now far stronger than it used to be and stronger

than North Korea. The risks of deterrence failure would be too great, given

Pyongyang's proclivities to attempt brinkmanship and intimidation. If we did

break the alliance, hypothetically speaking, another likely outcome would be

South Korean development of a nuclear arsenal, with further erosion of global

nonproliferation standards as a result. It is not a risk worth taking now.

It is also possible that

if North Korea greatly accelerated its production of nuclear bombs, of which it

is believed to now have about eight, or seemed on the verge of selling nuclear

materials to a terrorist group, the United States and South Korea might decide

to preempt with a limited strike against DPRK nuclear facilities. North Korea

might then respond in dramatic fashion. Such a war cannot be ruled out.

Given trends in the

military balance over the years, the allies would surely defeat North Korea in

such a war and then occupy its country and change its government. North Korea's

weaponry is more obsolescent than ever, it faces major fuel and spare parts

shortages in training and preparing its forces, and its personnel are

undernourished and otherwise underprepared. Yet horrible things could still

happen en route to allied victory. The nature of the terrain in Korea means

that much of the battle would ultimately be infantry combat. Whatever its other

problems, North Korea's rifles still shoot and its soldiers are still

indoctrinated with the notion that they must defend their homeland at all

costs. North Korea has built up fortifications near the DMZ for half a century

that are formidable and could make the task of extricating its forces difficult

and bloody. North Korea also has among the world's largest artillery concentrations,

and could conduct intense shelling of Seoul in any war without having to move

most of its forces at all.

Even nuclear attacks by

the North against South Korea, Japan, or American assets could not be

dismissed. Sure, outright annihilation of Seoul or Tokyo would make little

sense, as the United States could and almost surely would respond in kind, and

allied forces would track down the perpetrators of such a heinous crime to the

ends of the Earth. Any North Korean nuclear attack on a major allied city would

mean certain ultimate overthrow of the offending regime, and almost surely

death (or at least lifetime imprisonment) for its leaders once they were found.

But the point about nuclear war is that it wouldn't necessarily start that way,

and therefore it is not so easy to dismiss out of hand. Perhaps North Korea

would try to use one nuclear bomb, out of its probable arsenal of eight or so,

against a remote airbase or troop concentration. This could weaken allied

defenses in a key sector, while also signaling the North's willingness to

escalate further if necessary. It would be a hugely risky move, but not totally

inconceivable given previous North Korean actions.

Possible Chinese

intervention would have to be guarded against too. To be sure, in the event of

another Korean war, Beijing is not going to be eager to come to the military

defense of the most fanatical military dictatorship left on the planet. But it

also has treaty obligations with the North that may complicate its

calculations. And it is going to be worried about any possibility of American

encroachment into North Korean lands near its borders. For all these reasons, a

Korean war could have broader regional implications -- and pose huge threats to

great-power peace. This worry requires that Washington and Seoul maintain close

consultations with Beijing in any future crisis or conflict. But it also

suggests that U.S. and South Korean forces would want to have the capability to

win any war against the North quickly and decisively. That would reduce the

odds that China would decide to establish a buffer zone in an anarchic North

Korea with its own forces in a way that could bring Chinese and allied soldiers

into close and tense proximity again. If China insisted on creating such a

buffer zone temporarily, by the way, it would be preferable to allow the PRC to

do so rather than fight it to prevent such a possibility, in my judgment -- to

avoid turning this conflict scenario into a possible repeat performance of the

first Korean War.

So what does this all add

up to, in terms of American force requirements for a possible future Korean

contingency? Again, let me underscore my hope that such a horrible war will

never occur, and indeed my prediction that it will not. But hope is not a

strategy, as Colin Powell liked to say, and in addition often the best way to

preserve the peace when dealing with a state like North Korea is to be

absolutely clear in one's own resolve and absolutely prepared in military

terms. To accomplish this, necessary U.S. forces would have to be quite

substantial. They might focus principally on air and naval capabilities, given

South Korea's large and improved army. But they should also involve American

ground forces, since a speedy victory would be of the essence, and since as

noted the fighting could be quite difficult and manpower intensive. While South

Korea is very capable, and has a better military than does North Korea, it

would be important to win fast to limit damage to Seoul and to seal off North

Korea's borders in order to prevent the smuggling out of nuclear materials.

American ground forces

would also be important because American mobile assets (such as the 101st air

assault division and Marine amphibious forces) provide capabilities that South

Korea does not itself possess in comparable numbers. Perhaps fifteen to twenty

brigade-sized forces and eight to ten fighter wings, as well as three to four

carrier battle groups, would be employed, as all previous defense reviews of

the post-Cold War era have concluded. American forces might not be needed long

in any occupation, given South Korea's large capabilities, but could be crucial

for a few months.

U.S. Forces that were 15

percent smaller than today's would admittedly be hard-pressed in certain other

scenarios. They probably could not stabilize a country like Iran, for example.

In the unlikely but not impossible event that, due to dramatic Iranian

escalation in use of terrorism or weapons of mass destruction, we felt the need

to intervene on the ground in that country, a smaller U.S. Army and Marine

Corps would be a disadvantage. There is no denying it.

Even in this case,

however, we would not lack options. We would retain the ability, even without

allied help on the ground, to overthrow a regime such as that in Tehran that

carried out a heinous act of aggression or terror against American interests in

the future. Such a deterrent could also be useful against any other powerful

extremist government with ties to terrorists and nuclear ambitions or

capabilities, should it someday take power in another country (above and beyond

a current case like North Korea). The force would not be enough to occupy and

stabilize a country like Iran thereafter. And leaving it in chaos would hardly

be an ideal outcome. But this capability could nonetheless be a meaningful

deterrent against Iranian extremism, as we could defeat and largely destroy the

Revolutionary Guard and Qods Forces that keep the current extremists in power

if it ever became absolutely necessary. That translates into a meaningful deterrent

capability -- which is of course what we are after, since dissuading the

extremists in Tehran from worse behavior in the first place is our real goal.

To the extent the international community as a whole then saw the

reestablishment of order in Iran as important, it could if desired help provide

ground forces in a subsequent coalition to stabilize the place -- a job that

could require half a million total troops. (Thus, even today's American ground

forces would in fact be inadequate to the job of stabilizing Iran, which with

80 million people is three times as populous as either Iraq or Afghanistan.)

For missions like helping

stabilize a large collapsing state, perhaps Pakistan or Nigeria, smaller U.S.

ground forces could well prove sufficient as part of a coalition. That is, they

might suffice if part of the security forces of the state at issue remained

intact, or if a broader international coalition of states contributed to the

operation.

Consider one of these -- the

Pakistan scenario -- in more detail. Such a scenario is extremely unlikely; for

all its challenges, Pakistan does not appear on the verge of collapse. It is

also important to underscore, especially in this period of fraught

U.S.-Pakistan relations, that any international effort to help Pakistan restore

order to its own territory could only be carried out with the full

acquiescence, and at the invitation of, its government. That is because there

is no scenario I can imagine in which Pakistan's army would entirely melt away,

meaning that it would be a force we would have to reckon with and in fact want

to work with regardless of circumstances. It is also because the country is so

huge that the task would be unthinkably demanding, even with today's military,

if the U.S. and international roles were not primarily in support of indigenous

efforts. Even independent American writers like me can worry Pakistanis with

discussion of such scenarios, and the May 2011 killing of bin Laden only

exacerbates the Pakistani sensitivities to any discussion of scenarios that

would infringe upon their sovereignty. But we cannot avoid the issue.

Of all the military

scenarios that undoubtedly would involve U.S. vital interests, a collapsed

Pakistan ranks very high on the list. The combination of Islamic extremists and

nuclear weapons in that country is extremely worrisome. Were parts of Pakistan's

nuclear arsenal ever to fall into the wrong hands, al-Qaeda could conceivably

gain access to a nuclear device with terrifying possible results. The Pakistan

collapse scenario appears somewhat unlikely given the country's traditionally

moderate officer corps; however, some parts of its military as well as the

intelligence services, which created the Taliban and have condoned if not

abetted Islamic extremists in Kashmir, are becoming less moderate and less

dependable. The country as a whole is sufficiently infiltrated by

fundamentalist groups -- as the attempted assassinations against President

Pervez Musharraf in earlier days, the killing of Benazir Bhutto in 2007, and

other evidence make clear -- that this terrifying scenario should not be

dismissed.

Were Pakistan to

collapse, it is unclear what the United States and like-minded states would or

should do. As with North Korea, it is highly unlikely that "surgical strikes"

to destroy the nuclear weapons could be conducted before extremists could make

a grab at them. The United States probably would not know their location -- at

a minimum, scores of sites controlled by special forces or elite army units

would be presumed candidates -- and no Pakistani government would likely help

external forces with targeting information. The chances of learning the

locations would probably be greater than in the North Korean case, given the

greater openness of Pakistani society and its ties with the outside world; but

U.S.-Pakistani military cooperation, cut off for a decade in the 1990s, is

still quite modest, and the likelihood that Washington would be provided such

information or otherwise obtain it should be considered small.

If a surgical strike,

series of surgical strikes, or commando-style raids were not possible, the only

option would be to try to restore order before the weapons could be taken by

extremists and transferred to terrorists. The United States and other outside

powers might, for example, respond to a request by the Pakistani government to

help restore order. Given the embarrassment associated with requesting such

outside help, the Pakistani government might delay asking until quite late,

thus complicating an already challenging operation. If the international

community could act fast enough, it might help defeat an insurrection. Another

option would be to protect Pakistan's borders, therefore making it harder to

sneak nuclear weapons out of the country, while providing only technical

support to the Pakistani armed forces as they tried to quell the insurrection.

Given the enormous stakes, the United States would literally have to do

anything it could to prevent nuclear weapons from getting into the wrong hands.

Should stabilization

efforts be required, the undertaking could be breathtaking in scale. Pakistan

is a very large country: its population is over 175 million, or six times Iraq's;

its land area is roughly twice that of Iraq; its perimeter is about 50 percent

longer in total. Stabilizing a country of this size could easily require

several times as many troops as the Iraq mission, and a figure of up to one

million is plausible. However, that assumes complete collapse.

Presumably, any chaos

within Pakistan would be localized and limited, at least at first. Some

fraction of Pakistan's security forces would remain intact, able and willing to

help defend their country. Pakistan's military includes more than half a

million soldiers, almost 100,000 uniformed air force and navy personnel,

another half million reservists, and almost 300,000 gendarmes and Interior

Ministry troops. Nevertheless, if some substantial fraction broke off from the

military -- say, a quarter to a third -- and was assisted by extremist

militias, it is quite possible the international community would need to deploy

100,000 to 200,000 troops to restore order quickly. The U.S. requirement could

be as high as 50,000 to 100,000 ground forces. The smaller force discussed here

could handle that.

As noted, another quite

worrisome South Asia scenario could involve another Indo-Pakistani crisis

leading to war between the two nuclear-armed states over Kashmir, with the

potential to destabilize Pakistan in the process. This could result, for

example, from a more extremist leader coming to power in Pakistan. Imagine the

dangers associated with a country of nearly 200 million with the world's

fastest-growing nuclear arsenal, hatred of India as well as America, and claims

on land currently controlled by India. I do not suggest that we should create

the option of directly attacking such a hypothetical future Pakistan. That

said, some scenarios could get pretty hairy -- for example, if that future

government in Islamabad had ties to extremists and thought about supporting

them militarily. Certainly if such a future government was involved directly or

indirectly in attacking us, we would need options to respond. These should

include the possibility of a naval blockade and scale up from there as

necessary, along the lines of the capabilities discussed above regarding Iran.

Even more plausibly, it

is easy to see how such an extremist state could take South Asia to the brink

of nuclear war by provoking conflict with India. Were that to happen, and

perhaps a nuke or two even popped off above an airbase or other such military

facility, the world could be faced with the specter of all-out nuclear war in

the most densely populated part of the planet. While hostilities continued,

even if it would probably avoid taking sides on the ground, the United States

might want the option to help India protect itself from missile strikes by

Pakistan. It is even possible that the United States might, depending on how

the conflict began, consider trying to shoot down any missile launched

from either side at the other, given the huge human and strategic perils

associated with nuclear-armed missiles striking the great cities of South Asia.

The United States might or might not be able to deploy enough missile defense

capabilities to South Asia to make a meaningful difference in any such

conflict. But certainly if it had the capacity, one can imagine that it might

be prudent to employ it in certain circumstances.

It is also imaginable

that, if such a war began and international negotiators were trying to figure

out how to end it, an international force could be invited to help stabilize

the situation for a number of years. India in particular would be adamantly

against this idea today, but things could change if war broke out and such a

force seemed the only way to reverse the momentum toward all-out nuclear war in

South Asia. American forces would quite likely need to play a key role, as

others do not have the capacity or political confidence to handle the mission

on their own.

With forty-nine brigade

equivalents in its active Army and Marine Corps forces, and another twenty-four

Army National Guard brigades, the United States could handle a combination of

challenges reasonably well. Suppose for example that in the year 2015, it had

one brigade in a stabilization mission in Yemen, two brigades still in

Afghanistan, and two brigades as part of a multinational peace operation in

Kashmir. Suppose then that another war in Korea breaks out, requiring a peak of

twenty U.S. combat brigades for the first three months, after which fifteen are

needed for another year or more. That is within the capacity of the smaller

force -- though just barely. Specifically, after the initial surge to Korea,

the United States would by these assumptions settle back into a set of missions

that required twenty brigade equivalents in all for some period of a year or

more. The ground forces designed here would be up to the task.

Of course, with different

assumptions it would be possible to generate different force requirements,

making my recommended force look too small or alternatively bigger than

necessary. But the demands assumed above are not capricious. They are based on

real war plans for Korea, and very plausible assumptions about two to three

possible missions elsewhere. And they do not take the U.S. military too far

below levels that have recently been necessary for Iraq and Afghanistan, given

that recent history should remind us of any overconfidence about predicting the

end of the era of major ground operations abroad.

One final important point

demands attention in this analysis of scenarios around the world: what is the

role of U.S. allies in each of them? The fact that America has so many allies

is extremely important -- it signals that most other major powers around the

world are at least loosely aligned with America on major strategic matters.

They may not choose to be with us on every mission, as the Iraq experience

proves. But when America is directly threatened, as in 9/11, the Western

alliance system is rather extraordinary. This has been evidenced in Afghanistan,

where through thick and thin, even at the ten-year mark of the war, the

coalition still includes combat forces from some forty-eight countries.

Yet how much help do

these allies tend to provide? Here the answer is, and will remain, more

nuanced. The other forty-seven nations in Afghanistan have, in 2011,

collectively provided less than one third of all foreign forces; the United

States by itself provided more than two thirds. Still, more than forty thousand

forces is nothing to trivialize.

The allies have taken the

lead in Libya in 2011. But this may be the exception that proves the rule -- the

mission that they led was a very limited air campaign in a nearby country. The

French also helped depose a brutal dictator in Ivory Coast in 2011, and some European

and Asian allies as well as other nations continue to slog away in peace

operations in places such as Congo and Lebanon. The Australians tend to be

dependable partners, Canada did a great deal in Afghanistan and took heavy

losses before finally pulling out its combat forces in 2011, and over in Asia,

the Japanese are also showing some greater assertiveness as their concerns

about China's rise lead to more muscular naval operations by Tokyo.

For future American

strategy, however, we should keep our expectations in check. Overall, the

allies are not stepping up their game to new levels. Any hope that the election

of Barack Obama with his more inclusive and multilateral style of leadership

would lead them to do so are proving generally unwarranted. NATO defense

spending is slipping downward, from a starting point that was not very

impressive to begin with. The allies were collectively more capable in the

1990s, when they contributed most of the ground troops that NATO deployed to

the Balkans, than they are now.

The fraction of the NATO

allies' GDP spent on their armed forces has declined to about 1.7 percent as of

2009, well under half the U.S. figure. That is a reduction from NATO's earlier

figure of 2.2 percent in 2000 and about 2.5 percent in 1990. Secretary Gates

accordingly warned of the possibility of a two-tier alliance before leaving

office in 2011. Yet NATO is still an excellent insurance policy should trouble

loom in the future with China, Russia, or another power. As a time-tested

community of democracies sharing common values and historical experiences, the

alliance offers America a very useful anchor in sometimes unstable Eurasian

waters.

The bottom line is this:

When allies feel directly threatened, as Japan and South Korea sometimes do now,

they will pony up at least to a degree. South Korea in particular can be

counted on to provide many air and naval forces, and most of the needed ground

forces, for any major operation on the peninsula in the future. (South Korea is

less enthusiastic about being pulled into an anti-China coalition, and

Washington needs to watch not only the substance but even the tone of its

comments on this subject.) Taiwan would surely do what it could to help fend

off a possible Chinese attack, not leaving the whole job to the American

military in the event that terrible scenario someday unfolds, though it is

probably underspending on its military (see below for more on this). Many if

not most NATO forces will be careful in drawing down troops from Afghanistan,

making cuts roughly in proportion to those of the United States over the next

two to three years.

In the Persian Gulf, both

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have impressive air forces, with at

least one hundred top-of-the-line aircraft each. Both countries could certainly

help provide patrols over their own airspace as defensive measures in a future

conflict. If they had already been directly attacked by Iran, they might also

be willing to carry out counterstrikes against Iranian land or sea targets. But

again there are limits. Neither country trains that intensively on a frequent

basis with the United States to the point where combined combat operations in

limited geographic spaces would be an entirely comfortable proposition. To put

it more bluntly, we might have a number of friendly-fire incidents and shoot

down each other's planes. Even more concerning, if Iran had not actually

attacked their territories, Saudi Arabia and the UAE might prefer to avoid

striking Iran themselves first -- since once the hostilities ended, they would

have to coexist in the same neighborhood again. For that and other reasons, it

is not completely clear that we could count on regional allies to do more than

the very important but still limited task of protecting their own airspace. We

could hope for more, but should not count on it for force-planning purposes. A

similar logic would apply to Japan in the event of any war against China over

Taiwan.

Britain can be counted on for a brigade

or two -- five thousand to ten thousand troops, perhaps -- for most major

operations that the United States might consider in the future. Some new NATO

allies like Poland and Romania, and some aspirants like Georgia, will try to

help where they can, largely to solidify ties to America that they consider crucial

for their security. The allies also may have enough collective capacity,

and political will, to share responsibility for humanitarian and peace

operations in the future, though here frankly the record of the entire Western