Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 218

November 14, 2011

Former Army combat hospital commander convicted on several charges

The colonel was a grabber,

groper, and porn dog. Convicted on 14 charges, among them violating a "joint

ethics regulation, which was for having pornographic photos on his government

computer; sexually harassing three women, which is maltreatment; assault

consummated by battery on five women, which is not sexual; and numerous counts

of making inappropriate sexual comments and showing inappropriate photos," he gets 3 months in the hoosegow, a $30,000 fine,

and retirement from the Army.

No spin, maybe, but lots of junk

That's the National Park Service verdict

on Bill O'Reilly's error-filled history of the assassination of President

Lincoln. My favorite example: He has the president meeting in the Oval

Office-which didn't exist until the 20th century.

November 11, 2011

Thoughts of a military parent provoked by the Arlington funeral of my son's comrade

For personal reasons, I've been thinking a lot this week

about the families of those who deploy. So I was especially grateful to General

Barno for sharing this.

By Lt. Gen. David Barno,

USA (Ret.)

Best Defense guest columnist

Last month, I attended the funeral of Captain John

"Dave" Hortman, age 30, at Arlington National Cemetery. Dave was an Army

aviator, a decorated helicopter pilot with three combat tours in Iraq. He was

killed in a training crash at Fort Benning, Georgia on Aug. 8, scarcely 48

hours after the headline-grabbing crash of a CH47 helicopter in Afghanistan

that claimed the lives of 30 Americans. Dave's death and that of his co-pilot,

CW3 Steve Redd, garnered few headlines.

Dave and Steve were members of the Army's most secretive

helicopter unit, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment

(Airborne), the "Night Stalkers". Both were AH6M "Little Bird" pilots, flying

the Army's smallest and most nimble helicopter. They died flying in a routine

training event -- a fact that in some ways only adds to the anguish of their

deaths at a very young age.

Steve Redd, from Lancaster, CA was an experienced

special ops attack helicopter pilot, 19-year Army veteran, and fully mission

qualified aviator with thousands of flying hours. He had just remarried the

week prior to the crash. The photos accompanying his obituary -- of a laughing,

youthful 37-year old in Army Dress Blue uniform -- were taken at his wedding.

He left behind six children and stepchildren, and an amazing history over the

past decade that included nine deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

I accompanied my son and his fiancé to the funeral. My

son was in Afghanistan when his friend Dave died. As a fellow Little Bird

platoon leader, he led the memorial service in Afghanistan for Dave with the

deployed members of their unit -- a very tough experience for him. He had

redeployed back to the United States just in time to attend his friend's

funeral at Arlington. His fiancé -- herself a former Army scout helicopter

pilot, with two combat tours -- joined him. Both of them were very close to

Dave and his girlfriend.

Waiting around before the funeral's start with members

of Dave's and my son's unit provided me a brief glimpse into the parallel

universe occupied by so many in our military today -- particularly our special

operators. Dave's young fellow special ops pilots were gathered in their formal

dress blue uniforms, chests covered with ribbons, with gold-trimmed rank

epaulets dating from the Civil War on their shoulders.[[BREAK]]

Conversations before funerals are always awkward, but

this group was on tragically familiar ground. The 160th Regiment has

a large, black memorial stone on their closely guarded compound at Fort

Campbell. On it are the chiseled names of every one of the 91 aviators lost over

the thirty years of this unique unit's existence -- before the impending

additions of Dave and Steve.

Whereas chitchat before a civilian funeral might turn to

sports or the weather to skirt the somber import of the setting, the informal

repartee among this group was a bit different. Chief among the topics of these

fit and healthy young men was how remarkably well Dave had prepared his last

will and testament to cushion the blow of his death for family and friends.

Each of these young men in blues were now going to take

time to refine their own already up-to-date wills to better prepare in infinite

detail for the unthinkable. Hand-written farewell letters to family, sequences

of songs at the funeral, and how -- exactly -- the family was to be notified,

with whom present and in support -- all topics not common conversations among

young men and women attending funerals in Boise or Boston. Mixed in were

thoughts of future assignments, next deployments, decisions on getting married

or getting out of the Army, combined with updates on friends and classmates,

former unit members and mutual acquaintances. This was a military crowd, and

the year was 2011, and the last ten years of life for this group meant just one

big thing: war and training, training and war.

And of course, talk about Dave Hortman. Dave was a 2004

West Point grad, and a number of his friends and classmates -- those not

deployed -- were there to see him off. Dave's mother and stepfather were

present and surprisingly composed, along with his sister. A sizable contingent

from his hometown of Inman, SC, were there; Dave was the president of his Byrne

High School student body, class of 1999. And Dave's long-standing girlfriend was there,

herself an Army officer just back from Afghanistan, who had only two days

together with Dave before he headed off for his final mission.

As our group of about 70 followed the silver hearse

in our cars, conversations fell off. About a quarter mile from the gravesite,

we left our vehicles behind and proceeded forward on foot. A brief, solemn

ceremony marked the transfer of Dave's flag-draped casket from the hearse to a

horse-drawn artillery caisson, a nod to the past. Salutes were rendered by the

Army's 3rd U.S. Infantry, the "Old Guard," accompanied by subdued martial

music. A team of perfectly groomed horses capped by riders clad in formal Army

blues led our procession forward, followed by a somber Army marching band and a

platoon of Old Guard infantrymen with bayonet-tipped rifles sparkling in the

sunlight.

The troops' measured steps echoed off the blacktop road,

and many in our mixed crowd of dark suits and ties, dress blues and berets, and

cadet white over gray, fell unconsciously into step. As our small group moved

closer to the grave site, I noticed a small uniformed figure wearing four-stars

unexpectedly materialize in our midst. General Marty Dempsey, 37th Army Chief of Staff and his wife Deanie, had quietly joined our sad procession,

silently melding in with fellow mourners.

At the grave site, more salutes were rendered. The Old

Guard teams split up, expertly placing the casket over the open grave, while

the mounted caisson team quietly receded. A squad of infantry stood to one

side, ready to fire the traditional three volleys of seven in final salute. A

bugler, also bedecked in dress blues with bright ribbons, stood under nearby

trees, nearly out of sight. An unseasonably cool breeze rustled the leaves.

As the family took their seats opposite the casket

carrying the final remains of Dave Hortman, the crowd closed in, stepping

around the sticky mud from recent rains. An unrelenting parade of airliners

descending for landing at nearby Reagan National Airport bored through the sky

just overhead. The adjacent highway curving toward the nearby Pentagon provided

a muted backdrop of midday traffic. Closer in, the gravestones nearby marked

the final resting places of all too many young men and women, killed in action

in Iraq or Afghanistan. Dave would lie among those he served and supported,

fellow young warriors.

A clergyman from Dave's hometown gave a prayer, but his

words fell on many ears that were already numb. Colonel Matt Moten, who had

been Dave's sponsor and mentor on the West Point faculty while Dave was a

cadet, offered a touching eulogy recounting the impressive series of highlights

marking Dave's short life. The downcast mourners lifted their heads a bit,

hearing again about the love Dave engendered in his fellow cadets, fellow

pilots, fellow human beings.

Unsaid among the prayers or the tribute was the

inevitable crushing sense that this remarkably promising young man, and the

unique book that was his life, had now been forever destroyed with no new

chapters ever to be written. No marriage. No kids. No grandchildren. No more

choices or new possibilities. No more shared love, shared dreams, shared

sunsets.

The firing party volleyed off their 21 shots in three

sets with perfect precision. The bugler beautifully drew out the last notes of

"Taps." The soldiers at graveside precisely folded Dave's last flag and

presented it to Dave's company commander, a burly major with a chest covered in

combat ribbons. He knelt to present it to Dave's mom with words heard in

gentle, daily repetition at Arlington: "On behalf of a grateful nation..."

The crowd began to break up.

As our small groups quietly began the short walk back to

our cars, many paused to speak to Dave's mom. My son introduced himself, and

shared a few quiet words. He had gotten to know Dave when they were both

together in "Green Platoon," the six-month long, painfully intensive training

program required before Night Stalkers can begin operational flying. My future

daughter-in-law drifted toward Dave's grief-stricken girlfriend. They embraced

and shared quiet words, smiles, tears. My son joined them.

And my thoughts, unspoken, forged silently, caught in shared

glances between every military parent present: "And there, but for the grace of

God..." Sweating out that next night overwater training flight, that next live

fire exercise, the next combat deployment.

Holding our breaths, hanging on for a very, very long

war.

Guess what? I'm not crazy, I'm not using anti-depressants, and I'm not homeless -- I just happen to be a vet of Second Fallujah

There's a memorable line here: "I was able to graduate

college not despite being a combat veteran, but exactly because I am one."

By Edgar Rodriguez

Best Defense guest columnist

Every year, Veterans' Day stirs up mixed feelings for me. On

one hand, I am proud that our country takes a day out to honor those that have

served in uniform. On the other hand, I am dismayed that too often praise for

veterans feels empty and insincere. It is insincere because most Americans only

have a vague idea of the struggles that veterans go through. This lack of

understanding is particularly true in regards to combat veterans, a group that

I am a part of. I fought in the Second Battle of Fallujah in 2004 as a Navy

Corpsman attached to a Marine Corps unit. (Corpsman is Navy terminology for

medic.)

In meeting people I often find that they cling to two

stereotypes about combat veterans. One is of a broken-down drunk and the other

is of the post-military Rambo-like figure that is inches away from losing

control because he cannot readjust to American society. Often, they are

surprised that I do not fit into these stereotypes making comments like "You

don't look like a combat vet." Sometimes, people also ask strange questions

ranging from the highly inappropriate "Have you ever killed anyone?" to the

downright idiotic "What did you guys do on the weekends over there?" (Military

personnel typically work everyday when deployed to combat zones).

But most of all, I have found that people are often

genuinely perplexed that I have been able to be successful after leaving the

military "despite" being a combat veteran. It is almost as if I am obligated to

be doomed because of my combat service. I first encountered this attitude

during the final months of my enlistment. After informing my Chief of my

decision to leave the military he did everything he could to convince me it

would be a mistake. He even went as far as making me see our Command Master

Chief and speaking with him about my decision.

In my meeting with the Master Chief, he spoke of sailors that

he knew that had gotten out with intentions of becoming successful but had

their hopes dashed because they did not know how to function outside of the

military, emphasizing that as a combat veteran I would be especially prone to

failure. After sharing these sad stories with me he then went about offering me

pretty much anything I could have wanted as long as I reenlisted, at the end

saying, "Don't throw your career away Rodriguez. You could be a Master Chief!"

I thanked the Master Chief for meeting with me, but I told him that I still

intended to leave the military, leaving him noticeably disappointed. While I

know that the Master Chief only had the best of intentions, I found it unusual

and disheartening that he thought I could accomplish amazing things in uniform

but at the same time accomplish nothing worthwhile out of uniform.

As disheartening as the meeting with the Master Chief was, I

would later be grateful for it. The meeting prepared me for the array of uncomfortable

situations I encountered after leaving the military. Once, during a doctor's

appointment, the physician was surprised that I was a combat veteran and at the

same time had no prescriptions for Zoloft or Prozac, saying, "Are you sure you

were there?" Last year, during a research program at the University of

Maryland, I attended a group lunch with two professors that I was working with.

At one point one of them told me that if I had any issues that I should talk to

his assistant. I told him that the program administrators handled all the

administrative issues. To which he replied, "No, I mean if you have any veteran

issues. Like if you go crazy or something."

In speaking with fellow veterans I have found that these

sort of situations are not unique. These misunderstandings occur because the

gap between veterans and nonveterans has grown to the extent that most

Americans view veterans as an abstract idea instead of fellow citizens.

Currently, veterans are 2.6 percent more likely to be unemployed than

nonveterans and every day an average of 18 veterans commits suicide. I don't

believe that a society that truly understands and does right by its veterans

would have these sort of issues.

Society's lack of understanding makes the trauma of combat

worse for veterans. As a combat veteran, I understand this intimately. Before

Fallujah, I had intended to make the military a career. After Fallujah, I

decided to leave. I left because while I was always proud to be a Corpsman,

after Fallujah, I found that I had stopped enjoying it. Like many veterans, I

signed up for the GI Bill upon entering the military, although I doubted I

would ever use it. However, unsatisfied with the options left for me after the

military I decided to use it and give college a shot. It didn't look like I had

much of a chance of succeeding. There weren't any college graduates in my

family and I myself barely graduated high school.

I started off at my hometown community college and while I

did well, I found it academically unchallenging. I wanted something better so I

transferred to another community college eventually transferring to the

University of Florida. At the University of Florida I accomplished my goal of

getting a degree, graduating with high honors with majors in Political Science

and Linguistics. And I am proud to say that I was able to graduate college not

despite being a combat veteran, but exactly because I am one. Combat is one of

the most intense experiences a person can go though and it changes a person

forever. But while combat is an intense and negative experience, it does not

have to be destructive, it can it be constructive. If anything good can be

taken from war, then that must surely be it.

In the past, when speaking to people about the struggles

veterans face, I would sometimes say, "People are all about supporting the

troops, so long as they don't actually have to care." And while that statement

may seem mean and cynical, I thought it held a great deal of truth. I still do.

In my opinion, what veterans need are not acts of empty gratitude,

holidays, or memorials. What veterans need more then anything is to know that

they still have a stake in their own country after they've served. It is

something simple, but it is also something profoundly important.

Edgar Rodriguez is a Iraq War veteran and a University of

Florida graduate. He fought in the Second Battle of Fallujah in 2004 while

attached to the ground combat element of the 31st Expeditionary Unit. He

lives and works in Washington, D.C.

What we owe our returning veterans

By Tori Lyon

Best Defense guest columnist

As our troops come

back from Iraq, one measure of our integrity as a nation is how effectively we

welcome them home. Beyond a chorus of respect from business, government and

citizens for our troops, they are coming back to grim economic and social

realities leaving them more likely to be unemployed and homeless than average

Americans.

The vast irony is

that many service members who heeded the call to action post 9/11 are suffering

from the effects of an 11.7 percent unemployment rate, physical and mental injuries,

and terrible difficulties reengaging in the social and familial rhythms of

civilian life.

The result: a

disproportionate number of homeless veterans between the ages of 18-30. A new study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and Department of Veterans Affairs noted that while young veterans make up

only about 5 percent of the nation's veteran population, they constitute nearly 9 percent of

all former service members who are homeless. This doesn't count those who

"couch surf" with friends and family.

The problem will

not abate as another 50,000 troops stream home from Iraq and Afghanistan over

the next two years. How can we rise to the occasion to serve our veterans with

the same honor and dignity that they have shown us?

Based on Jericho

Project's 28-year

experience in helping formerly homeless individuals transform their lives -- and

our work in providing permanent supportive housing and comprehensive counseling

to over 200 veterans -- we believe that today's young veterans do not have to

experience the chronic homelessness that shamefully plagues those from the Vietnam era.

Instead, speedy and

intensive support can steer our homeless and at-risk veterans through the

challenges of transition and ensure that they do not settle into a permanent

state of homelessness. To accomplish this, start with the stabilizing

foundation of supportive housing within a community of veterans. Then, give

veterans access to the expertise needed to successfully tackle complex issues

such as substance abuse, mental health, and family isolation. And finally,

provide real-world counseling to fast-track veterans to jobs, internships, and

education where they can regain their confidence and get back on their feet.

Overall our young

veterans are known for their discipline, leadership, and courage. While

otherwise stressful, life in the military is also extremely structured. It

provides housing, training, employment, and community. So when a serviceperson

comes home it is an icy plunge into the relative chaos of finding affordable

housing, attainable jobs, and even coping with the anxiety of a crowd or loud

noise.

For those returning

to troubled homes or neighborhoods that were under-resourced to begin with, the

journey can be fraught with additional threats. While these veterans have become

accomplished, skilled teammates and leaders in the military, often their home

lives and neighborhoods now have even less margin for coping with joblessness,

addictions, and inadequate education.

What can be done? The

military can better prepare veterans for their return. Admirably the Department

of Defense is considering revamping its exit process to better connect

returning veterans to services and resources they need. We can also do a better

job of identifying those people who are at risk of homelessness

and introducing them to services early in the re-entry process. This can go far

in helping them to avert a condition that no veteran should bear.

At the same time,

employers can bring veterans' resumes to the top of the pile. Today's young

veterans make great hires, bringing maturity, crisis management skills and

loyalty to the table.

The Department of

Veterans Affairs has called for zero homeless veterans by 2015. With 75,000 veterans still on the

streets on any one night, it is a tall order, but together with the strategic

support of the government, businesses, social services and private citizens, it

is one that we must deliver.

Tori Lyon is

Executive Director of

Jericho Project

, a New York-based nonprofit ending

homelessness at its roots.

One way to observe Veterans' Day this weekend: Watch a great old war movie

We were sitting around CNAS this

week jiving about a

goofy list of best war movies that ran in the LA Times, and quickly drew up a counter-list

of our 10 favorite movies about the military.

One concern I have is that some

people will think watching a movie to commemorate veterans is disrespectful, or

in bad taste. I think not. Why? Because Memorial Day is our time to remember

the dead. Veterans' Day, by contrast, I think is to remember, thank, and

welcome home those who served and survived -- and so is both a commemoration and a

celebration. But I know others view this differently -- in fact, this came up last

night at a discussion I was at a Johns Hopkins SAIS.

World War II

Saving Private Ryan

Worth it for the first and last half hours alone. The middle

is actually pretty typical stuff.

Band of Brothers

Actually a television miniseries, but still one of the best

war films ever made.

Twelve O'clock High

Striking especially for its clear-eyed depiction of combat

stress.

Downfall

Hitler in the bunker. Contains one of the most parodied

scenes ever. See if you can find it.

Irregular warfare

The Wind That Shakes

the Barley

The Irish civil war actually didn't last long or kill many

people, compared to anything else on this list. But this is a powerful tale of

how revolutions eat their own.

The Battle of Algiers

Also one of the best movies ever made, plain and simple.

Bonus fact: Some of the actors actually are Algerian fighters playing the roles

they played in real life.

Zulu

A film any young officer should watch. A clinic on the

effectiveness of massed firepower.

Cold War

Dr. Strangelove

Stanley Kubrick proves it possible to make a humorous film

about nuclear war. Slim Pickens tops it off -- and a young James Earl Jones makes

an appearance.

Vietnam War

Apocalypse Now

Long and uneven -- like a lot of great art.

Post-Cold War world

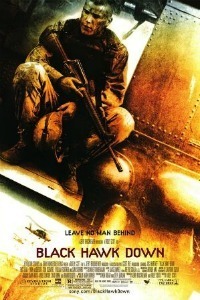

Black Hawk Down

About Mogadishu 1993. When Andrew Exum's wife wanted to know

what modern light infantry combat is like, he showed her this.

November 10, 2011

Israel striking Iran: Maybe it will happen?

Longtime grasshoppers know I've been skeptical

about Israel actually carrying through on threats to strike Iran in an attempt

to degrade the Iranian nuclear weapons program.

But I've heard two comments lately that have me

recalibrating a bit:

With the U.S. military out of Iraq in about six weeks,

there is a new opportunity for a direct flight straight across Iraq. "We have

no authorities or arrangements to defend the [Iraqi] skies," a U.S. Air Force

general helpfully

notes. The Iraqi military isn't capable of stopping an Israeli air flotilla

or maybe even detecting it, if done right. Israel even could put up some

refuelers over the western desert, with some fighters protecting them. And

maybe even take over an airstrip out there to use for emergency landings, or

combat search and rescue. If you find this argument persuasive, then New Year's

Eve may be the time to do it. I mean, who is going to stop them? Syria has its

own problems, and Saudi Arabia probably would be happy to help.

Also, I think the more Israel talks about doing it, the

more inured Iranian air defenders become.

But keep in mind that Fuller was right, and Afghan security forces really are bad

Ok, we had some fun yesterday

with the defenestration of General Fuller, but this note arrives this morning

and it is sobering:

Fuller told the truth

on this one and was mangled as a result. It's no secret that the Afghans want

to drain every last dime out of the US and the ISAF nations.

The major problem

with the Afghan National Security Forces -- other than the rampant corruption,

attrition and neptotism -- is the utter lack of institutional control in almost

all of their organizations. This is an inward-looking problem, however. The

major outward-looking problem associated with the ANSF is that we have built

multiple organizations that have no chance at long-term success because they

cost too much to sustain. Once the money dries up, the ANSF is toast and

everyone who worked in Kabul or with the Afghans at the Corps level or above

knows this.

Fuller was relieved

not because he told the truth - the Generals are not idiots who don't understand

what the situation with the ANSF is and will be. He was fired because he took

his frustrations out in public and embarrassed the Afghan Government, the US

government and military and the ISAF leadership.

Congress knows

everything that is going on with the ANSF. A DoD special Inspector General

makes quarterly visits to Kabul and releases quarterly

reports that are available on-line. If they wanted to end this kabuki

dance, they could slash funding and tell the Afghans to deal with the

consequences. Instead, we continue to pump money into the system. There are

systemic problems with the ANSF that have no solutions - unless you really want

to station 50,000 US Troops there for the next 30 years.

Two ways to access that 1983 Army War College paper on bad brigadier generals

In response to popular demand by you demanding Best

Defenders, the Army has created two ways to read that 1983 report I discussed

the other day about how one-quarter

of new brigadier generals were considered stinkers by battalion commanders who

had served under them.

One way is to click on this

link for a PDF. Or, if you are feeling particularly adept, you can follow

these instructions offered by the friendly folks at the Army's Military History Institute:

"Actually, anyone can access it from any computer. Just lead them to the

research portion of our website www.acho.army.mil & have them follow the instructions:

1. Click on the big "Digitized Materials" button

2. Enter the name "Reid, Tilden R." in the white

search box & click the "search all digitized material" box

immediately below

3. Scroll down the

results list and open the document!"

Army commander in Germany bounced

He acted inappropriately.

That is such a Washington word. I wish the Army would stop using weasel words.

Kind of amazing how many people are stepping down, maybe

seeing their public lives coming to an end these days. Paterno and his

president. Papandreou. Eddie Murphy. Heavy

D. Herman Cain? Rick

Perry? Berlusconi?

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers