Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 175

June 25, 2012

The Syrian shootdown of the Turkish jet

My first thought was that Syria

shot down the Turkish F-4 because the Turks were

probing Syrian air defenses. But then I remembered that the U.S. aircraft

patrolling the northern Iraq no-fly zone flew out of Incirlik, Turkey, which

meant that they zoomed along the northern Syrian border for years. We must have

learned an awful lot about Syrian operations, and shared almost all of it with

our Turkish friends, and other members of NATO.

So what more might there be

to learn? Probably a probe to see how much deterioration there has been in Syrian

defenses in the last year. But that

would be a good use of a drone, no? (And are we sure there was a pilot in that F-4?)

The Israelis clearly also

know a lot about Syrian defenses.

Meanwhile, Turkish jets conducted

air strikes in northern Iraq.

Interesting neighborhood.

June 22, 2012

Mini 6.22

A few words in defense of Colin S. Gray's essay on COIN and our future strategy

By Adam Elkus

Best Defense COIN respondent

Colin S. Gray's

recent article in Prism, when read in context with his

other works, reveals much about how an inadequate grasp of strategic theory

compromised the counterinsurgency debate. Tom

has graciously provided me space to elaborate on why Gray's corpus

is valuable

for American

defense policy

and strategy.

COIN as Concept Failure

It is pointless to argue, Gray claims, whether or not COIN

has failed or succeeded. This is because COIN is not a concept. Debaters argue for or against COIN, a position as ridiculous as

arguing about whether anti-submarine warfare is inherently good or bad. As Gray

observes, COIN is not an internally coherent set of ideas. It's just a

descriptor for what armies do to counter insurgents. If this sounds a bit

reductive, consider that the enormous losses suffered by the Allies at Cambrai

in 1914 did not constitute proof tank

warfare itself had failed, nor did decisive combined arms tactics in the

Gulf War prove that tank warfare was successful.

The merit or demerit in COIN "cannot sensibly be posed as a

general question." Insurgency has been a constant feature of strategic history,

and will likely continue to

be. Whether or not to intervene in another state's internal politics is a

question best left to historical circumstance and it is impossible to put forth

one policy solution that will hold for any and all cases. In any event, the idea

that one has a choice to engage in COIN is also a matter of context. Domestic

insurgencies always must be countered as a matter of basic political survival.

It is a category error to argue that COIN is inherently more

political than interstate war, as this implicitly uses a war's intensity as the

defining measurement of how much it is dominated by politics. All wars involve

the use of force for political purpose, are shaped by context, and feature two

forces seeking to impose their will on an adversary. In other works,

Gray has sensibly noted that the supposed differences between irregular and

conventional warfare are ultimately cosmetic. Categorizing wars according to

the predominant combat style of one or more of the belligerents leads to

analytical confusion. For example, the idea of "cyberwar" erroneously implies that combat

action will solely be limited to computer hackers volleying computer network

attacks against each other across the digital ether.

Weapons obtain meaning only through the strategic effects

they enable, making it difficult to categorize a war solely through military

technology. In American operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, conventional

platforms, skills, and specialties were used against primitive opponents -- and

tactical innovations pioneered there will likely play prominent roles in major

war. The spectacle of Canadian Leonard tanks firing on Taliban guerrillas and

the reverse engineering of counter-IED technology into tools for destruction

of conventional air defenses should be sufficient demonstration of the

arbitrary distinction between conventional and irregular challenges.

One consequence of this categorical confusion is the idea

that that one side's tactics and technologies should be defeated through

deliberate mirroring. Networks should defeat networks, governments and third

parties must out-govern insurgents, and so on. But there is nothing essential

to a given war's policy or strategy that demands a perfectly symmetrical

response. This is obvious when the enemy is a global terrorist organization -- no

one would argue the U.S. should carry out suicide bombings. It is less obvious

when the enemy is a guerrilla organization contesting control with a government

and a third party force. Counterinsurgents do not have to "out-govern"

insurgents simply because the enemy uses shadow governments for strategic effect.

The enemy does have a vote, but that vote should not unnecessarily narrow

counterinsurgent strategy.

COIN and Strategy

Gray's previous works have emphasized that although the

logic of strategy is timeless, strategy in practice defies the American obsession

with definitive principles of war. Context rules all, and principles of war are

in reality only principles of warfare

valid for certain temporal, political, cultural, and material circumstances.

The only principles of war that truly

survive are so general as to be practical

nubs: war is a political act conducted for political purposes, war is a

cultural undertaking, etc.

The COIN debate has essentially been a tireless search for

eternal principles. But this debate, as Gray, David Kilcullen, Sebastian Gorka

have all argued,

rests on a tiny sliver of contemporary military history. Insurgencies differ

radically according to context in strategic history, and dependence on a small

set of cases (Algeria, Vietnam, Malaya) exacerbates the already Sisyphean

search for principles of COIN warfare. A universally "right" way to conduct

COIN does not exist, not least of which because the idea supposes a Platonic

ideal that can be divorced from political and cultural circumstance. Gray argues that the sheer diversity of

phenomena herded under the common moniker of "insurgency" inherently creates a

plurality of strategic methods that can guide COIN tactics.[[BREAK]]

The diversity of strategic approaches to dealing with

insurgency, Gray points out, means that "best practices" can only be realized

on the level of tactics. As Gulliver of Ink Spots observed,

all armies need to know how to shoot, move, and communicate. Even then, the

usefulness of tactics is contingent on how they enable strategic effect

determined by policy. There are tactical best practices for countering

insurgencies utilized by other powers that American policy has determined to be

out of political bounds. Other governments will reject tactics for what may

seem like completely arbitrary reasons to Americans. The dispute between the U.S.

military and the Afghan government over night raids in Afghanistan is a case in

point -- a tactically sound approach that favors an American strategic objective

may not serve Afghan national and personal interests.

Gray echoes Joshua

Foust and other regional analysts of Afghanistan in noting that discussion

of COIN within the context of current operations has really been a provincial

debate over American COIN doctrine. Policy

and strategy, which by necessity are formed by the conversation between

national interest and regional knowledge, sadly emerged only as adjuncts to

theological debates about COIN tactics. Doctrine is important, but even

successful doctrine is too narrow a prism to look through when examining war.

Gaining Strategic Advantage

What does Gray's view of strategy have to say about how

America should understand the business of winning (or losing) wars that feature

COIN? First, a basic truth of strategy is that it deals with, but is not ruled by, warfare. States can

sometimes win war by dominating the warfare, but this is not always the case.

The Israelis arguably won the warfare in 1973, but the strategic shock

inflicted by the Egyptian assault had far-reaching political effects. Likewise, the Chinese performed poorly

in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese conflict but still rattled

the Vietnamese enough to gain the Chinese political object. Finally, as the

United States discovered at the end of the 1991 Gulf War, even victors do not

always gain peacetime objectives they seek. And success always has some kind of

unintended consequence. Above the tactical level, an objective concept of

victory does not exist. Victory and defeat are governed by only by political

context.

All this is also true of counterinsurgency. Strategy is

enabled by tactics, and military defeat of insurgents does not guarantee

strategic defeat because the physical ability to annihilate them requires a

degree of decision that small-scale counterguerrilla operations cannot always

provide. The Chinese communist ability to survive numerous encirclement

operations in the Chinese civil war, coupled with their greater faculty with local

deal-making among powerful elites, enabled them to survive and eventually

outgrow their nationalist enemies. As Lukas Milevski observed,

battles make up the raw material of warfare but do not necessarily equal the

whole of war. Hit-and-run attacks, sabotage, targeted killings, battle

avoidance, and raw attrition are not chivalrous but also inflict important

physical and psychological losses. The story of guerrilla warfare is mostly

(but not always) a story of erosion. The victor is often the one still left standing.

While guerrillas can sometimes win through strategies of

erosion, so can governments. Destruction of enemy resources, safe havens, and

population control as a means of restricting enemy movements are all ways

governments impose cumulative material, psychological, and political costs on

insurgents. Through controversial, intelligence-based leadership targeting, the

use of "pseudo-gangs,"

and informers are all part of the toolbox governments and their allies use to

gain some measure of control over

the adversary. And control -- gained either through erosion or decisive warfare -- is

crucial to success in COIN. The public are not just spectators to warfare in

COIN, and control is one of the various means governments and insurgents use to

gain support and legitimacy.

Perception, Legitimacy, and Politics

"Legitimacy" should not necessarily be understood solely as

a synonym for "consent of the governed." Rather, legitimacy can have a variety

of meanings among various audiences. But one side's staying power is crucial to

local perception of legitimacy. Gray's most important point is that success in

COIN is not likely if prior or parallel nation-building is a

precondition for victory. Analogies to nation-building in Europe and Asia miss

the point: many of the most successful efforts occurred after a great deal of

bloodletting to gain physical control. Control enables police to create order,

tax collectors to receive revenues, and institutions to be built. And even then

the outcome is not guaranteed. The Union military overawed the South but prewar

political and cultural institutions reasserted themselves with malicious energy

during Reconstruction.

COIN efforts can be crippled by bad politics, but COIN also

suffers when physical control cannot be exercised. While military effects can

sometimes gain political decision, it does not follow that political work can

always compensate for military failures. Tactics must serve strategy, but the

converse is that strategy without sound tactics is also dangerous. One Afghan

example that Gray repeatedly returns to is the failure to destroy the enemy

sanctuary in Pakistan. Strategic defeat of insurgents is impossible without

tactical actions to neutralize the major source of their political power: the

perception they can and will outlast their American adversaries in a war of

attrition.

Perceptions in Afghanistan rest on material realities. The

Taliban are unlikely to perceive themselves to be defeated if they can

regenerate their power in secure sanctuaries. And as Foust suggests,

Afghans are unlikely to be convinced of government staying power if the Taliban

can consistently mount terrorist operations around the pinnacle of Afghan and

Coalition political power in Kabul. It is true that defeat in the battle of

perception can raise the cost of coercion. But good works do not guarantee

cooperation, and accidental cultural gaffes and collateral damage do not

inherently lead to conflict. In fact, sometimes the opposite can occur in both

cases. Why? The behavior of populations in war is motivated by a variety of

factors that include political mobilization, sectarian and family loyalties,

safety, and material interest. Outside forces must deal with these motivating forces but should not assume they can

easily alter them.

The challenge, as in any other kind of war, is to use force

in a manner that enhances rather than detracts from control. This does not mean

assuming that the population is the center of gravity. Taking the human terrain

into account is simply smart politics, something armies and their political

masters should always be cognizant of. Insurgents are successful when they use

existing political forces to their advantage, but governments can also do so

even in when they are unable to obtain consent. Israeli military and civilian

intelligence efforts rest in large part on extensive

exploitation of political and social friction between Palestinians.

Consequently, a popular uprising defeated Hosni Mubarak because he lost control

of Egyptian elite politics.

Finally, as Gray notes, if tactical setbacks cannot be tactically rectified, the problem is the

policy or strategy rather than cultural awareness or COIN deficits. If a

general or a politician cannot solve the problem caused by a "strategic"

corporal, it is not primarily the enlisted man's fault that the war effort

collapsed. In Somalia, the tactical disaster of Mogadishu

would not have mattered if the war had greater support in American domestic

politics. Once the war shifted from a humanitarian operation into military

operations, a gaping hole in the "strategy

bridge" left the entire structure vulnerable to fog and friction and enemy

adaptation.

Conclusion

Gray's essay is first and foremost a plea for COIN theorists

to consider the canon of strategic literature and human experience beyond Iraq

and Afghanistan. We ought to carefully reflect on his words before we find

ourselves encountering the same problems on new military frontiers. Strategic

theory will not guarantee victory, but it can help us shed illusions about what

force and persuasion can and cannot achieve.

Adam Elkus is a PhD student at American University. He

blogs at

Abu Muquwama

,

CTOVision

and

Information Dissemination

on

strategy, technology and international politics.

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: Navy handler Sean Brazas laid to rest and saying goodbye to MWDs Nina and Paco

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

MA2 Sean Brazas, who was

killed in action in Afghanistan on May 30th, was laid to rest this week at

Arlington National Cemetery. Earlier in the week, family and friends from his

hometown in Greensboro, NC gathered for a memorial service. His high school

also paid tribute,

flying its flag at half-mast.

Brazas's parents and sister spoke

to a local news team about their son -- who leaves behind his wife and their

13-month old daughter -- and how proud they were of him. "If I could turn out to

be half the man..." his father started before stopping to regain his composure.

"He got to be married and have a family, just not long enough... At the end of

the day you want your kid back, it's that simple."

Two other fallen servicemen were remembered in a memorial

service held on June 1, on a military base in Afghanistan -- MWDs Nina and

Paco. Both of the dogs' handlers got up and spoke about their fallen partners.

Sgt. Adam Brown, Paco's "one and only handler," said, "There's only a few times

in my life that I've come across an opportunity that's changed my life, Paco

was one of those opportunities." Nina's handler Sgt. Daniel Wilker said he knew

the two shared a special connection when Nina accidentally bit him one of the

first times they trained together. "She laid next to me and had this look on

her face that she was so sorry."

Among the mourners at Arlington National Cemetery and among those

gathered to pay respects in Afghanistan, were fellow canine handlers and their

dogs.

Rebecca Frankel, on leave from her FP desk, is currently writing a book about military

working dogs, to be published by Free Press.

The Rumsfeld-Adelman feud

One of the more interesting relationships in DC is the

running battle between Donald Rumsfeld and his former aide and friend Ken

"Cakewalk" Adelman. As I recall, it went public when Adelman, once a very loud

Iraq hawk, began questioning the Bush

team's conduct of the Iraq war around 2006. For example, he said of the

Bush administration's national security officials that, "They

turned out to be among the most incompetent teams in the postwar era. Not only

did each of them, individually, have enormous flaws, but together they were

deadly, dysfunctional."

The

feud recently surfaced again in the letters section of the Wall Street Journal. One letter this week began, " Ken Adelman's rebuttal (Letters, June

18) of Donald Rumsfeld's June 13 criticism of the United Nations Convention on

the Law of the Sea repeats two persistent myths about this deeply flawed and

unnecessary treaty . . . . "

This may seem an

obscure fight between figures of the past, but could be relevant if Mitt Romney wins the presidential election. He strikes me as the kind

of guy who would think it would be great to have Rumsfeld around as an elder

statesman.

June 21, 2012

Don't just get rid of West Point as a 4-year college, get rid of ROTC, too

By “Townie76”

Best Defense guest provocateur

Three years ago, Tom proposed shuttering West Point as an expensive anachronism. At the time I thought he was barking up the wrong tree, but after reflection upon my own career as an army officer, I think he is on to something. It is not just West Point that should be done away with, it is also ROTC that should go.

Before anyone get's their panties all knotted and wadded up, let me be up front: I am a product of ROTC, and I attended one of the "senior military colleges" -- the Virginia Military Institute. What I am proposing will have an impact on my alma mater, as well as the other "senior military colleges."

I think that America's fiscal resources could be better utilized in the following manner:

1. Those interested in commissioning would enlist in the armed forces, attend basic training, and advanced individual training. They would then be assessed into an officer development program and transferred to the National Guard or Reserves and receive a scholarship that would pay tuition, room and board, and books and laboratory fees at the college or university of their choice. While they could major in any subject they choose, they would be required to complete required courses as part of their development program.

2. They would have four years to complete their degree.

3. They would continue to drill with their assigned National Guard or Reserve unit.

4. Upon receiving their degree they would then proceed to the campus of the USMA at West Point (Naval Academy for USN & USMC; Air Force Academy for USAF) where they would undergo a year long course of instruction and evaluation leading to commissioning. It would be comprised of tactical and academic instruction along with extensive field operations where they would have to demonstrate their mastery of tactics and their leadership ability.

During the year they would receive not only academic evaluations, but also evaluation of their leadership ability through 360 degree assessments. The last three months would be an extended field exercise equivalent to "Ranger School" which all would have to satisfactorily complete in order to be commissioned. At any point up to the day of commission they could be dismissed from the program for academic, conduct, or leadership failures.

5. Once a year the army (navy and marine corps; air force) would commission all the officers of that years cohort of officers of the line. Some would be detailed to the Reserves and National Guard to fulfill their mandatory commitment of 10 years of commissioned service. All would be required to serve a total of ten years as a commissioned officer which could be divided between the active and reserve components.

6. Those who failed to complete their assessment for commissioning would be inducted into the regular army where they would serve for four years until such time they paid back their "college assistance."

It is my humble opinion I would have been a better Lieutenant and a better officer if I had I gone through a "Sandhurst"-like program.

My plan would guarantee that everyone had an appreciation what it was to be "the last man, in the last squad, of the last platoon." Moreover, it would level the playing field, everyone would have the same date of rank and where one went to college would not matter. Most importantly it would give us well-rounded officers who were connected to society and not isolated from it.

After graduating from the VMI, “Townie76” served in both the active and reserves, retiring as a colonel.

A good Army officer goes bad? Or slides back to his old ways? Either way, it's sad

Capt.

Charles Eadie, a previously enlisted soldier who graduated near the top of his West

Point class in 2007, and then went

to the London School of Economics, was busted and charged with selling

anabolic steroids to an

undercover police officer in Columbus, Georgia. He has pleaded not guilty.

Here is

an interview he did about his career when he was deployed to

Afghanistan in 2010. In it, he mentions that he had a "troubled past" and

actually was on probation when he first tried to enlist. "There is definitely a

darker path that I could have taken in life," he says, somewhat ominously.

You BD

hardasses probably all want to throw the book at him. Maybe I am just a softie

but I wonder if he was trying to feel the thrill of living close to the edge, a

bit of the adrenaline of combat.

Why you all were wrong about McGurk

I was surprised when you all wrote so many comments disagreeing with me on Brett McGurk's nomination to be ambassador to Iraq.

Now Fred Kaplan comes forward to explain why you all were wrong.

June 20, 2012

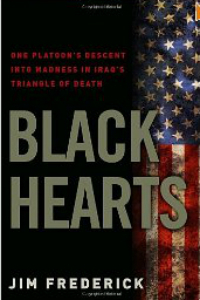

Back to 'Black Hearts': Why this book stands out so much as a study of the Army

By "PKL"

Best Defense guest explicator

Another damn army scandal, another damn book about it; worse, a book

with a lurid title: Black Hearts, and an even more

lurid subtitle: One platoon's

descent into madness in Iraq's Triangle of Death. War weariness

and a proliferation of books about individual actions in Iraq and Afghanistan

seem to have left this book in publishing's

no man's land: number 286,309 in the Amazon hit parade this month. Hard to

understand why more than a quarter million other books at Amazon outsell it.

This seems a pity. Black Hearts is the battle name adopted by the 1st battalion, 2nd brigade combat team, 101st Airborne.

The book by senior Time magazine editor Jim Frederick is described by senior

British war and military correspondent Max Hastings as matching In Cold Blood, Truman

Capote's 1965 account of the murder of the Clutter family on their farm in

Holcomb, Kansas. Three Black Heart soldiers murdered the Iraqi al-Janabi family

of Yusufiyah, a father, mother and six- and 14-year-old daughters. The cousin

who found their corpses in March 2006, demented by grief and his desire to

offer some propriety to the scene, snatched a kettle and ran back and forth to

a nearby stream, gathering water to put out the fire that had consumed every

part of the 14-year-old's upper body, other than her fingertips.

As Frederick recounts matters, the army was called in minutes later,

and contrary to physical evidence on the scene, was content to attribute the

crime to other Iraqis. Then a Black Heart's conscience started to trouble him

and the reality of what happened to the al-Janabis came to light. Those who

entered the house and killed them were prosecuted and in his masterwork,

Frederick sets the incident in the context of army administration as it was in

2006.

Why his book is a masterwork, its ten-page foreword makes clear.

At sundry officer levels, the 101st's leading edge units

were administered in an atmosphere of public insults and sarcasm. 1000 men were

required to do the work that by 2008 was being done by 30,000, and those lonely

first thousand were bleeding heavily. Black Hearts platoons lost their leaders

to enemy action one by one; three months after the al-Janabis died, three

Americans were overrun by insurgents. One died during the battle. The survivors

were later mutilated, beheaded and their bodies were booby-trapped.

In Tokyo, having read reading brief wire service reports about the

al-Janabi family's deaths and the later small battle, Frederick, then Time

Magazine's bureau chief in that city received a phone call from army captain

James Culp, a former infantry sergeant turned lawyer who had been assigned to

defend one of the three Bravo Company men accused of the Yusufiyah atrocity. He

wanted Frederick to come as a reporter, "if not for the sake of my client, then

for the sake of the other guys in Bravo." He did, and later, he gained

assignment to Iraq both as a reporter and, in time, in preparation for what

turned out to be his book.

His research occupied much of the next three years, and what marks the

difference between Black

Hearts and most other books

on similar subjects was that he started contacting101st men to see if they were

willing to talk. Surprisingly, they were.

Frederick writes: "Despondent over being judged for the actions of a

few criminals in their midst, they were eager to share their stories ... They

were generous with their time, unvarnished in their honesty ... arguing that I

could not properly understand the crime and the abduction if I did not

understand their whole deployment.

"[As well,] I could not understand (the errant) 1st platoon if I did not understand 2nd and 3rd platoons, who had labored under

exactly the same conditions but who had come home with far fewer losses and

their sense of brotherhood and accomplishment intact."

In some cases he interviewed individual veterans repeatedly, building

a history, scaffolding it with context. He spoke to relatives of the al-Janabi

dead and attended the trials of the men charged with killing the little family.

He used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain reams of official documents.

"Every opened door led to a new one," his foreword recounts. "Most

soldiers and officers I talked to offered to put me in touch with more. Some

shared journals, letters and emails, photos ... classified reports and

investigations."

Honorable men. The heart and sinew of Black Hearts is those few sentences. The conclusion

of this multidimensional examination of army practice is its head. So also is

its conclusion: "I had thought that the Army way was for everyone to accept a

small piece of the responsibilities for any debacle truly too big to be of one

man's making ... [and so,] make the fiasco something that the army could study

and learn from. But the ordeal generated so much bile and rancor for so many

people that the army seems more interested in forgetting about the tragedy

entirely, than in ensuring that it never happens again ...

"[M]any men feel that blame was unfairly pushed down to the lower

ranks and not shared by a higher command they believed was also culpable."

The ten-page foreword is a clear and fair introduction to the rest of

the book's contents.

Those closing remarks match what General Antonio Taguba told West

Point in an oral history

interview available on the web. If you question Frederick's conclusions as

reported in his book, ponder the calm and confident retired general telling his

interviewer that his investigation of Abu Ghraib satisfied him that army abuses

there were widespread through Iraq, and that, given permission to do so, he

would certainly have sheeted home some responsibility for them to general

Ricardo Sanchez, V Corps' 1st

Armored Division commander

when those abuses were in flower.Keep in mind also that Frederick was writing down his conclusions before

the 5th Stryker

murders of Afghan civilians were widely known, and before this year's Panjwali

massacre, in which 16 Afghan peasants were killed. All these actions were

performed either by an individual or a very small and aberrant criminal group.

Virtually all other soldiers despise them. And, as Frederick suggests, their

recurrence suggests the army isn't very good at forestalling future such

outbreaks, staining as they do the name of an entire military arm of this great

nation.

Keep in mind also that Frederick was writing down his conclusions before

the 5th Stryker

murders of Afghan civilians were widely known, and before this year's Panjwali

massacre, in which 16 Afghan peasants were killed. All these actions were

performed either by an individual or a very small and aberrant criminal group.

Virtually all other soldiers despise them. And, as Frederick suggests, their

recurrence suggests the army isn't very good at forestalling future such

outbreaks, staining as they do the name of an entire military arm of this great

nation.

Skipper of USS Essex dumped the old school way: For lousy ship handling

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers