Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 179

June 6, 2012

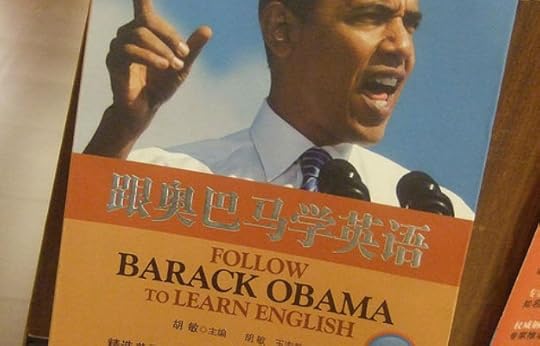

David Sanger's 'Confront and Conceal' made me wonder: Should Barack Obama be seen as our first Asian president?

Here is a link to my review

in today's New York Times of David

Sanger's new

book on President Obama's foreign policy. As I say in the review, the

strongest part of the book is the stuff about the joint Israeli-American

cybercampaign against the Iranian nuclear infrastructure. (Btw, the copyeditor

for the book review told me while editing it that she had checked and this is

the first time the Times has used the

word "cybercampaign" to describe a series of cyberattacks, which surprised me.)

An interesting side observation in the book is Sanger's

comment that Obama's "legendary self-control .

. . makes him seem like a politician from a more buttoned-down,

controlled Asian environment."

I wonder: Is Obama actually our first Asian

president?

Three terms that wouldn't occur to me in describing the U.S.-Pakistan relationship

"We are trying to have an open,

transparent, and mutually beneficial relationship with the U.S. based on our

national interest," the Pakistani prime

minister told officers at that country's Command and Staff college. Well, that

is good news!

But then I read more of his comments and I realized Prime

Minister Gilani probably was engaging in what one of my sisters used to call

"grandma talk," to signify when my mother would say the opposite of what she

actually meant (e.g., "You look thin!"). For example, the Pak PM said, "we

want to play our role in the stability and peace in Afghanistan." And he said

he believes that "our children and the generations to follow will lead a

peaceful and productive life." Just use the Grandma interpreter, and you

will understand what he is saying.

No matter what Gentile and others wish, counterinsurgency just isn't going away

By Col. Robert Killebrew, USA (Ret.)

Director, Best Defense office of Market Garden studies

Even

as the war in Afghanistan continues to boil, the defense intellectual crowd has

wandered into an unnecessary and counterproductive debate about whether the

United States can avoid being involved in future counterinsurgency wars. "Unnecessary and counterproductive" is an appropriate

description of a largely contrived argument that distracts brainpower from

focusing on the real issue -- the changing nature of warfare in the emerging

century.

Of course the U.S. is going to be involved in counterinsurgency

in the future, just as we will be involved in all kinds of wars, period.

Insurgency is one of the oldest forms of warfare -- an uprising against a

government. But the terms under which rebellions are put down are

changing fast. Until very recently, the Westphalian attitude of the times

reinforced the authority of governments to suppress internal rebellions without

too much regard to sensitivities or legal restraints; both the American revolution and Napoleon's war on the Iberian Peninsula, for example, featured

insurgencies that were brutally suppressed by regular forces, but there was no

thought of holding commanders -- much less governments -- responsible for brutal

reprisals.

All that is changing as the world is changing. Nuremburg mattered a lot.

The WWII Germans felt no need for a counterinsurgency doctrine -- their

reaction to resistance in occupied countries was just to round up hostages and

shoot them -- but after the war some commanders were held to account despite the

argument that they were only obeying orders, a legal landmark. Punishing

commanders for massacres was not only simple justice, but an indication that

civilians were no longer just an incidental backdrop to a war. Rather individuals

began to be regarded as having rights that continued even during warfare, and even when they rise against

their rulers. That principle of the universality of human rights in war

is a historic change that is now considered applicable even in modern struggles against the medieval brutalities of al

Qaeda or the Taliban. In the 21st century, international law is

struggling to replace the Westphalian compact as the new firebreak against

indiscriminate barbarism.

This is the nub of the challenge of counterinsurgency (or COIN, as it is known

by its unfortunate acronym). People may rise in rebellion against their

government, or against the government of a conquering power, but the

government's reaction can no longer be to slaughter them wholesale -- as is

happening now in Syria -- for two reasons. First, sanctions to punish

indiscriminate killing are spreading and increasingly effective, as the Syrian

leadership will eventually learn. This is the emergence of the new

sensibility of human rights, which will accompany widespread political changes

in the new century (as we are seeing today in the Arab world). Second,

and more practically, killing alone doesn't work against a determined

opposition -- never has, in fact. Insurgency, which stems from political

dissatisfaction, ultimately requires a political solution, so the greatest part

of any successful COIN campaign requires political solutions that address the

fundamental issue that started the insurgency in the first place, while

security forces -- both military and, increasingly, police -- try to contain

violence and drive it down to tolerable levels.

All this can frustrate soldiers when they get tasked to fight insurgents under

restrictive rules of engagement and with little backing from the political

class. An American military that in the 1990s trained for violent

high-tech short wars has been understandably frustrated to find itself bogged down

in an inconclusive, decades-long war that its political leadership has either

misunderstood or backed away from. The "COIN is dead" school of

military thought is a reaction to that frustration -- and to the damage that our

protracted focus on counterinsurgency has done to other, essential military

capabilities -- but it is wrongheaded for a number of reasons.

First, insurgencies aren't going away, and the United States will fight more of

them. For a variety of reasons, populations and individuals today are more

empowered than ever before, and governments are under more pressure to meet the

expectations of their people. Political dissatisfaction, mass migration,

widespread armaments, and crime are producing an international landscape that

will challenge weak governments for decades, and often insurgencies will be

supported by outside powers hostile to the United States or our friends.

Aggression by insurgency is an old strategy that will recur.

Second, because they're hard doesn't mean we can't win them. In fact,

insurgencies are more unsuccessful than otherwise. When states react to

insurgencies wisely, insurgents are usually defeated. Colombia is in the

process of defeating an insurgency that was threatening its survival a decade ago.

The once-inevitable revolution in El Salvador is long over. The

government of Iraq is consolidating power and looks to be on a success curve.

In all cases, political reforms marched hand with increasing military and

police capabilities and the collapse of the insurgency's outside sponsor. One

significant point for military planners is the degree to which military power

must be blended with the state's police and other civil powers, which until

recently was contrary to U.S. military tradition and practice. Nothing changes

tradition and practice, though, like hard lessons in the field.

Thirdly, American military (and political) planners and doctrine-writers must

understand that the U.S. is not, and never will be, the primary COIN force --

our best course will always be to work "by, with, and through" the host

country in the lead, with Americans playing a supporting role. This is a

profound change for soldiers who are trained to take charge of dangerous

situations. Even in Afghanistan and Iraq, where U.S. forces faced the worst-case

COIN scenario possible -- the absence of a government to support -- ultimate

success has not been, and will not be, possible until the local government

shoulders the load. We were far too slow to understand this in these two

theaters, and too slow to plan and resource local leaders once we did

understand it.

Finally, wars are never fought the same way twice, though armies invariably

prepare for the last one. The American military faces a daunting

challenge -- to correctly draw lessons out of a decade of experience in two wars

that will prepare them for the next one, without falling into the last-war trap

that a decade of war has prepared for us. Additionally, the military

services know they will be the ones on the ground compensating for weaknesses

in the other branches of government. Getting this right in the manuals

will be very tough, and may challenge deeply-held Service beliefs and

organizational imperatives; a noted COIN authority is fond of reminding his

friends "counterinsurgency is more intellectual than a bayonet

charge." That is certainly true -- but no reason to walk away from

it.

June 5, 2012

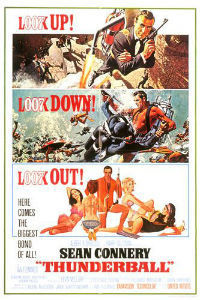

Your questions for Crumpton -- and his answers about Tora Bora, torture, Cheney, 'Thunderball,' and good books on intel

Tom: As I expected, your

questions for former CIA

officer Henry Crumpton, posted as comments or e-mailed to me, were better

than mine. So you guys got to ask most of them. Here goes.

Best Defense reader: Do you know who actually made the decision

not to reinforce your people at the battle of Tora Bora? How engaged were

Secretary Rumsfeld and President Bush in the operational details, and did they

intervene at any point to specify a different approach or overrule General

Franks?

Henry Crumpton: I spoke

with General Tommy Franks, CENTCOM Commander, about the need for more American

forces at Tora Bora within hours of the request from my men in

Afghanistan. The details of that conversation are in the

book. I do not know if he spoke with the president, secretary of defense, or others about my request.

Several days earlier I did have a

conversation with President Bush in the Oval Office about the possibility of

enemy leadership escaping into Pakistan. I showed him maps of the area

with possible escape routes, explaining that it would be impossible to seal

that border although I noted that more recon/interdiction forces would be

helpful. We provided our best intelligence, including confirmation

of UBL's presence, and offered our best recommendation but this was ultimately

a military decision. Finally, please note that the Tora Bora battle was

an overwhelming U.S. victory with hundreds of the enemy killed and no U.S. KIA --

but a victory blemished by UBL's escape.

Best Defense reader: Why haven't we experienced a Mumbai-like

attack, with a suicidal group creating havoc in an urban area with small arms

and explosives? Is something like that not important to any terrorist group (if

not, why not), or are our defenses too effective, or something else?

Crumpton: The Mumbai style attack,

with a team of well trained operatives armed with small arms attacking an urban

area, has not happened primarily because UBL preferred a massive attack inside

the U.S. against an iconic target, an attack with great symbolic and strategic

value. Now that he is dead, there might be emerging AQ leaders who opt

for more traditional commando-like attacks aimed at dispersed, soft targets. The 2009 attack at Fort Hood, with 13 dead, is one example of an

isolated, successful terrorist attack in our homeland. There have been

other attempts, including approximately 10 failed attacks in NYC in the last

decade.

There would have been many more

attempts, some probably successful, if not for our offensive CT operations

abroad. There are daily operations in South Asia, Yemen, Somalia,

and elsewhere, which keep the enemy at bay. Many of the enemy must worry

about surviving (some of them, of course, do not survive) rather than attacking

our homeland.

Tom: I know that torture has long existed and been used by

governments. But I never thought that the United States would make the use of

torture official policy. Do you think I am being naïve?

Crumpton: No, you are not

naive. You raise an important point, which prompts important

questions. What is torture? (My personal view is that none of the

U.S. government approved enhanced interrogation techniques were torture -- except for water

boarding.) Are these techniques effective? (I have no experience in

these operations, but many CIA officers whom I trust believe that they are

useful. In my role as an intelligence customer while coordinator of counterterrorism at the department of state, I benefited from many reports that

came from CIA detainees.) If these techniques are effective, should we

use them? (This is a decision for the U.S. policy makers, reflecting the will of

the American people, because it goes to who we are as a society. The CIA

and even the president alone certainly should not make the decision. In

our deliberations we must ask what price we will pay for intelligence. And, what price will we pay for not using such techniques.)

Best Defense reader: It appears likely [Crumpton] crossed paths with Ali Soufan, the former

FBI agent who has been a critic of CIA. I wonder what Crumpton's opinion of

Soufan's reliability might be.

Crumpton: Yes, I did encounter Ali Soufan when he deployed

as part of a large FBI contingent to Aden, Yemen, in October 2000 to

investigate the al Qaeda attack on the USS Cole. I was there leading the

CIA response team. My impression of him at that time was positive: He was knowledgeable, hard working, and his Arabic language was especially

useful. I have no way of measuring his reliability, however, during that

time or more recently. I have not read his book or otherwise paid

attention to whatever criticism of the CIA he has made.

Best Defense reader: Was Osama bin Laden's significance

known or understood at the time he was in Sudan? Why did President Clinton

decline Sudan's offer to turn him over to us?

Crumpton: The CIA knew about

bin Laden and his emerging role as a terrorist leader when he was in

Sudan. There was extensive intelligence reporting about him. I

cannot measure the specific impact of that intelligence, however, on the policy

makers who received the reporting -- although I can surmise it was minimal

given the weak policy response then and throughout the coming years, until

9/11.

Tom: Was VP Cheney's office a help or a hindrance to your

operations?

Crumpton: The vice-president seemed

quietly supportive of our Afghanistan campaign during the fall of 2001. He seemed to endorse my briefings with nods of approval and occasional

constructive questions and comments. He was always polite and encouraging

to me in these meetings. His leadership role in the U.S. invasion of Iraq,

however, set back our efforts in Afghanistan and hurt our intelligence and

foreign policy relationships with many Middle Eastern and other allies.

Best Defense reader: What do you miss most about the clandestine

life?

Crumpton: My friends in the CIA,

other U.S. government organizations, and foreign allies, including some heroic unilateral

sources. I do not miss U.S. government employment. My 26-year run was

wonderful, the realization of a boyhood dream to serve our nation. But,

now, I love the private sector, especially serving some great clients with great

missions of delivering free market power to many parts of the world. I

also love the creative freedom and opportunities available to a small business

leader and entrepreneur.

Tom: Which national security commentators do you follow, if any?

Crumpton: David Ignatius,

Fareed Zakaria (read his book: The

Future of Freedom), Tom Friedman, Elliot Cohen, Peggy Noonan, Steve

Coll, David Brooks, Lee Kwan Yew, Joseph Nye, Martin Indyk, James Fallows,

Zbigniew Brzezinski, and of course Sun Tzu.

Tom: What is the origin of the feud between you and David Kilcullen?

Crumpton: I did not know there

was a feud. Perhaps a brief history? I met David at a Johns Hopkins

SAIS conference in 2005 and soon thereafter hired him as a strategist working

for me when I was the coordinator for counterterrorism at the department of state. This was an unprecedented bureaucratic and political feat --

hiring an Australian national in that new role -- thanks to the intervention of

DNI John Negroponte and others. This effort, I believe, helped advance

the important security relations with one of our most important and effective

allies, Australia. David proved very competent and worked tirelessly,

helping me develop regionally-based counterterroism strategies.

In early 2007 General David Petraeus

called me and asked if I would loan David to him, to help craft a

counterinsurgency plan for Iraq. I agreed. A couple of years

later, after I had launched my consulting firm, I hired David again. He

worked for me in that private sector capacity for a year, then departed to

pursue other work. I hope that he will continue to contribute to our

collective understanding of irregular warfare.

Best Defense readers: What is your favorite movie about

intelligence operations? Your favorite novel? And which do you think are the

worst?

Crumpton: Movies. Thunderball....okay...okay....not a

great instructive film or a great work of art, but it had a profound influence

upon me as a young boy and helped inform my dreams of national service and

grand adventure. One of the great suspenseful espionage movies: North by Northwest. One of the

worst spy movies: Syriana.

Books. The novel Body

of Lies by David Ignatius,

particularly the focus on the relationship between the CIA operations officer

and foreign liaison chief, and the operations officer and a local unilateral

agent. Other novelists such as Le Carre and Greene are superb artists but

I grow weary of the pitiful moral angst, self-loathing, and pessimism that

permeates their novels. For a great instructive biography, read Sir

Richard Francis Burton by Edward Rice. What a brilliant, brave

operative who epitomized empathetic understanding of diverse cultures and the

collection of deep, profound intelligence. The worst spy book . . . too

many to list.

Best Defense reader: What advice would you give to a young

person who wants to become an analyst for the CIA?

Crumpton: Know yourself. If you don't get that right, nothing else

matters including your analytical judgments, which will be skewed and

contorted. Knowing yourself requires constant testing and measurement,

which only happens in stressful, real-life environments. So get out of the

classroom and employ and hone your intellectual virtue. Then, reflect

upon your actions, recalibrate your course as needed, and practice and practice

with deliberate reasoning, emotional value, and enthusiastic optimism. Never quit -- while remembering that a sense of discipline will keep you alive

and a sense of humor will keep you sane.

Weird stuff on the Kazakh-Chinese border -- and also 'Buddhist vigilantes' in Burma

I usually write this blog around 6 or 7 in the morning.

There are days when my eyes kind of glaze over as I look at the overnight world

news headlines: Bombs in Baghdad, drone strikes in Pakistan, and plane crashes

in Nigeria.

So when some news comes out of an unexpected place, I pay

attention. Few places on the planet can be more remote than a border post

between Kazakhstan and China. That's where 14 soldiers and a game warden recently

were killed in an unexplained incident. Reuters suspects

drug smuggling. For all we know, could be a feud with aliens.

Another item about another obscure location from the same

agency reports that "Buddhist

vigilantes" attacked Muslims in western Burma. Isn't "Buddhist vigilantes" a

bit like "Marine Corps pacifists"?

A hidden cost of the V-22?

The new amphibs (I still think we should just call them

"small carriers") won't

have a well deck. Two questions: Is this to better accommodate the V-22?

And how serious is the

loss of the well?

(HT to "Semp Fi")

June 4, 2012

To fix PME, decide whether you are training or educating officers -- and do it!

By LTC

Jason Dempsey, USA

Best

Defense department of PME reform

The Scales

and Kuehn

discussion on PME has piqued a long-running interest of mine in the failures

of professional military education (PME). While obviously I am more with Scales

in my overall assessment of the system, I think Kuehn's piece helps frame the

debate because it highlights some of the confusion over the purpose of PME.

Specifically, it seems our colleges cannot decide whether they are in the

business of training or educating. This confusion has led to a muddied

curriculum and a faculty that is required to cover both educating and

training, and which as a result fails to do either one very well. This was

briefly mentioned in the panel comments, but I think deserves further

elucidation as the root source of the failure of PME (and I'll limit my focus

here to CGSC).

For

starters, let's look at the faculty. These are typically officers on the verge

of retirement who have been out of the operational force for several years and

are interested in academia, but have not yet completed advanced degrees or had

any classroom experience outside of the military system. This places them on

the fringes of both the operational force and academia. Yet we ask them to

cover both the 'core curriculum' and electives, essentially

guaranteeing mediocrity in both areas. Kuehn's call for a renewed

emphasis on the split between the core and electives portion of CGSC is

refreshing, but doesn't go far enough.

The

'core curriculum' at our service colleges should be restructured with a

singular focus on training officers for the command and/or staff

responsibilities they are about to assume. This is largely the case now, but

the focus should be similar to what occurs at the pre-command courses, where

senior leaders rotate in to provide insights, mentorship, and current

operational perspectives. At CGSC this would mean that commanders and their

staffs at the brigade and battalion levels would be the ones rotating in to

instruct and to facilitate scenario-driven staff exercises. This would ensure

that students received the most relevant training available while reinforcing to the officer corps the importance of taking the time and effort to properly

train the next generation.

As for

the elective portion of PME, at least at CGSC, the list of offerings should be

considered an outright embarrassment. Again, because of not understanding the difference

between training and education, valuable time -- that could be spent broadening -- is

instead spent on 'courses' that are mere recitations of doctrinal manuals or

job descriptions and are about as far as you can get from anything broadening

or academically rigorous ('Logistics for the Battalion XO', etc.). This is not

to say that there are not great instructors and courses out there (the history

departments are indeed strong, and I'd be remiss not to tip my hat to Don

Connelly for carrying the torch for the study of civil-military relations).

But, as Kuehn notes, these few good courses are drowned out in a curriculum

that could only charitably be described as vo-tech for field grades. So long as

we aren't kidding ourselves that this is a broadening experience or equivalent

to education, fine, but if we are serious about the need to get officers to

think critically and out of their comfort zone than it is this portion of PME

that needs the most restructuring.

Personally,

I'd be for replacing the elective periods with sending officers off to get one

year graduate degrees -- let the experts in education educate, while the Army

focuses on training. But in the end, no significant reforms will take place until we

recognize the differences between training and education, and decide which our

PME system should focus on.

Lt. Col. Jason Dempsey is

a career infantry officer and a graduate of a couple levels of PME, including

the infantry officers basic course, the amphibious warfare school at Quantico,

and CGSC. He also holds a PhD from Columbia University and is the author

of Our

Army: Soldiers, Politics and American Civil-Military Relations.

The court-martial of Col. Johnson

The court-martial of Col.

James Johnson III, once the high-flying commander of the 173rd

Airborne Brigade, is scheduled to begin next

week in Germany. (His wife helpfully gave the investigatory report to the Fayetteville

Observer.)

He faces 27 charges of false official statements, forgery,

fraud, conduct unbecoming, adultery and

such. I've been searching my memory and can't remember a similar case. The one

that comes closest is the general who was based in Turkey, retired, and then

about 15 years or so ago got recalled to active duty to face a similar set of

charges.

Chandrasekaran and Coll on Afghanistan

You couldn't find a better duo in journalism to discuss the

Afghan war. Here is your big

chance, later this month.

While I am at it, here is the RSVP form for the CNAS annual conference, the

Woodstock of wonkery. It is on June 13.

June 1, 2012

Were the Israelites a 'Melian'-like group on whose world view our culture stands?

One of my side projects this year has been reading the

entire Bible

cover-to-cover for the first time. Starting at the beginning and staying with

it throughout, I find, makes the whole thing more coherent. (It also sometimes

feels surprisingly current: "Damascus

is waxed feeble, and turneth herself to flee, and fear hath seized on her."

-- Jeremiah 49:24.) I mean, ripped from today's headlines.

The other day I was struck by Jeremiah 46:13, which offers

an aside about the Lord telling the prophet that the "king

of Babylon should come and smite the land of Egypt." That passage reflects

the larger fact that a big chunk of the Old Testament is about the Jews being

squeezed between the Persians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, and the

Egyptians. In other words, about a small, endangered people facing the

predations of empires.

This made me think about the revenge

of the Melians,

another small people

who were caught between greater powers, and who also got squashed. What does it

mean that the Old Testament, the bulk of the central book of our culture, is

written from the point of view not of one of the great powers, but of a small

nation that is eventually destroyed by them? Is this why we instinctively side

with the rebels and against Darth Vader? If so, how does that unconsciously

shape our strategic thinking? Are we inherently more likely to succeed when

aiding rebels than we are when fighting them?

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers