Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 181

May 29, 2012

Nothing about NATO here. How come?

I wrote nothing about the

recent NATO summit -- and not a single reader asked how come. That's

interesting because clearly the readers of this blog are interested in national

security issues.

I suspect that you, like me, just found the whole thing

boring. In fact, the main thing that interests me about Europe right now is its

economic crisis, not its security pretenses.

That said, I still believe what one sage once told me about

the purpose of NATO: "They keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the

Germans down."

May 25, 2012

A Memorial Day thought: Maybe Pittard really does speak for us on suicides

By Jim Gourley

Best Defense no. 1

commenter

There is profound irony in the recent unfortunate

remarks made by Major General Dana Pittard the week before Memorial

Day. After attending the funeral service of a

soldier who'd committed suicide, the 1st Armored Division commander issued a

post on his official blog describing suicide as "an absolutely selfish

act."

"I am personally fed up with soldiers who are choosing to take their own

lives so that others can clean up their mess." He wrote. "Be an adult, act like an adult, and

deal with your real-life problems like the rest of us."

Pittard later retracted

his statements with "deepest

sincerity and respect," but he did not explicitly apologize. Just as notable was the absence of any

remarks from senior army leadership disavowing that Pittard's comments in any

way represent official army policy or views. Perhaps it would have mitigated the damage done by the ill-conceived

remarks, but the fact that no one said anything -- especially so close to a time

when we are about to remember those who have made the ultimate sacrifice in

service to their country -- may in fact be the bitter medicine we need to

take.

The truth is that Pittard's comments actually do serve as a

representation of the military's perception and approach to suicide in an

indirect yet disturbing way. The remarks

themselves were odious, but the loudest statement was the muted response from

army leadership. It is incredible that,

after a decade of war in Afghanistan, it was unclear to Pittard that such views

are not only unacceptable but wholly incorrect. It is equally shocking that no other senior leader felt compelled to

issue an immediate and damning response. It is not the case that Pittard's remarks are generally accepted as

correct (though more than one senior leader likely agrees with them), but it is

painfully evident that senior leaders have not determined what the correct

perspective is. They certainly have not

articulated it.

On the whole, Americans take off work for Memorial Day but they don't

actually take the time to remember. We

visit cemeteries and monuments to talk about the price of freedom, but we don't

reflect on the cost of war. We hail

those who made the ultimate sacrifice, but we don't consider how to account for

the sacrifices of those who died by their own hand. It is a bureaucratic bridge too far for the

army to ever establish a connection between combat events and an active duty

service member's suicide in garrison, let alone the suicide of a veteran after

separation. Yet countless are the

mothers, fathers, spouses, and children who will say that these men and women

"died over there" and "never really came home." That leaves us with the prospect that this

weekend we'll remember fewer than ten

percent of the service members who made the ultimate sacrifice over the

last ten years. It's not something we

like to talk about. So we don't.

This irony will be the enduring, tragic legacy of our wars in

Afghanistan and Iraq. I have written

about the issue at length on this blog.

The Department of Defense, VA, and multiple independent researchers have

made an exhaustive effort out of collecting data on combat trauma and

suicide. Yet for all the statistical

certainty with which we can speak about suicide among veterans and service

members, we are paralyzed when it comes to determining how we feel about it as

a country. The people we've lost to

suicide knew how they felt when they joined the military. It's reasonable to assume most of them did

not feel selfish. They definitely knew

how they felt the moment they took their own lives.

The Pittard episode is an allegory for America's response to service

member and veteran suicide. I neither

believe him nor the majority of American citizens to be malevolent. Nor do I believe that the thoughts he

expressed were motivated by cruelty. But

cruelty does not require intent, and it is often the consequence of a

neglectful or inconsiderate mindset.

Having committed it accidentally, we view the cruelty as something best

forgotten quickly. Pittard did exactly

that, trying to move on without dwelling further on the past. He immediately followed his retraction with

comments about this weekend's upcoming Memorial Day events at Fort Bliss,

seemingly oblivious to any connection between the two. Like anyone else caught in a public gaffe,

Pittard would like to carry on as if nothing happened.

In this way, he is the avatar for our collective discomfort with our

treatment (or lack thereof) of those living with combat trauma. With the exception of a few landmark

occasions like Memorial Day and September 11, this has been the

standard practice of Americans for the last ten years. How ironic then that we should refer to

combat trauma as an "invisible wound" and over 6,000 veteran suicides

each year as the "unseen tragedy."

In that way, a nation's day of remembrance would take on an unbearable

melancholy were its citizens brought to remember that the preponderance of its

fallen service members died on home soil. By living in denial we protect the greater population from bearing that

burden of remembrance. Therein lies the final irony of Pittard's remarks. Any rebuke of his momentary lapse in judgment

would necessarily be an indictment of our decade of willful negligence. Maybe the senior leadership was hesitant to

say that he does not speak for us because they know that he speaks from among

us. In that regard, our silence is bred

of shame.

Memorial Day: The heart of a Ranger

Read this short

comment from Michael Yon, dammit.

War Dog of the Week: Tam, the dog who would not leave his handler behind

By Rebecca Frankel

Best Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

Lance Corporal James Wilkinson was a mere two meters away

when a roadside bomb

exploded, sending shrapnel spray into his hip and stomach, severing the

femoral artery in his leg. The blast launched Wilkinson off his feet, and though

he was able to take stock of the severity of his wounds, he blacked out before

he could call for help.

When he came to he found Tam, the yellow Labrador who'd been

his bomb-sniffing partner during their three months in Afghanistan, standing

over him. After the explosion Tam, who had not been injured in the attack, stuck

close by his handler through the billowing black smoke and barked "like mad,"

not only bringing Wilkinson back to consciousness, but also drawing their

fellow soldiers to his aid. They treated him quickly, applying a tourniquet to

his leg and getting him onto the U.S. Black Hawk helicopter that

brought him swiftly to Camp Bastion's military hospital.

The doctors who repaired the extensive damage done to his

hip and leg told Wilkinson, a dog handler with the 104 Military MWD Squadron of

the British Army, that if he'd arrived at the hospital "a minute later he would

be dead." His surgeries lasted an entire day.

Originally from Yorkshire, Wilkinson, 26, is still working

through his recovery. "It is a slow process," he told

reporters, "but I am getting there. I am

walking, which is the main thing. A lot of guys who get caught by IEDs

(improvised explosive devices) end up losing a leg or both."

Unfortunately, his career as a military

dog handler is over. Wilkinson suffered nerve damage in his leg

and still has shrapnel in his body. The Army has classified him as

"non-deployable." His wife Kerry has left the Army and hopes that her husband

will decide to join her in civilian life and return to his former job as a

gamekeeper. They are expecting their first child this summer. But Kerry, who

was also a handler with the 104, knew Tam and saw

the connection between her husband and his canine

partner. "They had a great bond. Jim loved that dog."

There is no questioning the role the dog played in saving

this soldier's life. Of Tam, Wilkinson says, "He was my world. He was a good

companion and I trusted him."

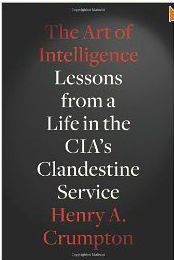

What would you ask Hank Crumpton?

This is your big chance. I expect to do an e-mail interview

in the next few days with former CIA clandestine operator and counter-terror

chief Henry

Crumpton. It occurred to me that many of you, with all your varied

experiences, probably would have better questions than me.

So send your questions along, and I will add them to my

pile, and select the best 10.

May 24, 2012

Obama and American exceptionalism at AF Academy: Will we bear any burden?

The

president was selling red meat at the Air Force Academy graduation yesterday. I guess this is part of running toward the

center as the general election campaign begins.

Yesterday's

Blue Plate Special was American

exceptionalism, with all the trimmings. You can see how this Kennedy-esque

stuff might drive both the isolationist right and the pacifist left nuts. I

liked it better when he was channeling

Lincoln:

" You would think folks understand a basic truth

-- never bet against the United States of America. (Applause.) And

one of the reasons is that the United States has been, and will always be, the

one indispensable nation in world affairs. It's one of the many examples

of why America is exceptional. It's why I firmly believe that if we rise

to this moment in history, if we meet our responsibilities, then -- just like

the 20th century -- the 21st century will be another great American century. That's the future I see. That's the future you can

build. (Applause.)

. . . I see an

American century because no other nation seeks the role that we play in global

affairs, and no other nation can play the role that we play in global

affairs. That includes shaping the global institutions of the 20th

century to meet the challenges of the 21st. As president, I've made it

clear the United States does not fear the rise of peaceful, responsible

emerging powers -- we welcome them. Because when more nations step up and

contribute to peace and security, that doesn't undermine American power, it

enhances it.

. . . And finally, I see an American century

because of the character of our country -- the spirit that has always made us

exceptional. That simple yet revolutionary idea -- there at our founding

and in our hearts ever since -- that we have it in our power to make the world

anew, to make the future what we will. It is that fundamental faith --

that American optimism -- which says no challenge is too great, no mission is

too hard. It's the spirit that guides your class: "Never

falter, never fail." (Applause.)

That is the essence

of America, and there's nothing else like it anywhere in the world.

A reading list: The best books on PTSD

By Lt. Col. Robert Bateman, USA

Best Defense department of strategical

and historical affairs

Now, obviously

(given my own book which dealt heavily with the topic of veterans who falsely

claim PTSD), I agree that there is room in the system for correction. Sometimes

it is too easy to fool the VA, for example.

But just as with

the machining tolerances within the extremely reliable AK-47, you need some

slack in the system to ensure that everyone who should be taken care of

actually is taken care of. The AK never jams because it is machined to a looser

standard than our own Western, weapons. A little extra gas escapes, and because

of this the weapon does not have the amazing accuracy of our weapons. But also

because of this slack built into the system, you know that when you pick up an

AK out of the dirt, that it WILL fire every single bullet in the magazine. An

American weapon, picked up out of the dirt or dust or swamp, not so much. The

American weapon must be clean, and well cared for, because there is no

tolerance built into the system, which means some rounds won't fire, and that

can be a bad thing.

Much the same

might apply to the definitions of PTSD and how they are applied. Do we want the

"perfect" system, which sometimes causes catastrophic jams, or do we want a

system that has some leaks and inefficiencies, but works for 100 percent of the rounds

you put through it?

In partial answer to a colleague's query, let me offer a short annotated

bibliography.

Eric Dean, Shook

Over Hell, Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Harvard

University Press, 1997): This is a pretty decent book, although the author is

not entirely conversant in the then-latest medical scholarship. Also, frankly,

he could have done entirely without the opening and closing artificiality of

examining PTSD from Vietnam. It was enough that he uncovered, and demonstrated

the broad and then-well-known phenomena of "nostalgia." Essentially,

from all contemporary descriptions, this was PTSD as it was diagnosed in the

post-Civil War era in the United States. Given this evidence of widespread PTSD

(including cases ending in suicide) in the Civil War generation, were they just

softer than the Mexican-American War and War of 1812 generations?

Peter Barham, Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War (Yale

University Press, 2004): The focus here is on those slackers and weak-willed

types, the Edwardian Tommies who fought in the trenches of WWI for the

British. Barham's work is dense, but readable, and discusses the

evolution of attitudes towards these "slackers." (Or, as was the case

with much of the military -- then and perhaps now -- who want to ignore the

issue, the lack of evolution.) The work focuses upon asylums, mostly after the

war.

Peter Leese, Shell Shock, Traumatic Neurosis and the British Soldiers

of the First World War (Palgrave MacMillan, 2002): Covers much of the

same ground, but more in depth on how the topic was dealt with during WWI, with

only about 54 pages devoted to post-WWI period. Still, it's a shorter and

somewhat more digestible book, so if you wanted just one book on the topic as

it related to the British in WWI and after, I'd go with this one. Since Leese

(writing from his faculty position in Krakow, Poland) and Barham (writing,

then, in the UK) were writing at nearly the same time, their works overlap, but

not excessively so, and they do not reference each other.

Now, on the changing of attitudes towards all veterans and their malaise,

there has been some evolution. For a good multinational examination of the

history, I recommend a fairly dense academic anthology: David Gerber,

ed., Disabled Veterans in History (University of Michigan

Press, 2000). Fascinating, if constrained by the nature of an anthology, I'll

list just a few chapter titles and let you decide if you want the book.

"Heroes and Misfits: The Troubled Social Reintegration of Disabled

Veterans of World War II in The Best Years of Our Lives" by

the editor, Gerber. Geoffrey Hudson, "Disabled Veterans and the State in

Early Modern England." Isser Woloch, " 'A Sacred Debt': Veterans and

the State in Revolutionary and Napoleonic France." etc.

Now, on the

American side of the equation we have some pros and we have some cons. It is

also an area where my personal interaction puts me in the middle, and so my

analysis here must be balanced against my personal friendship with both,

opposing, authors.

First, and foremost, are Jonathan Shay's books, Achilles in

Vietnam and his later Odysseus in America. (Personal

disclaimer: I know, and like, Jonathan. He has been to my house, broken bread

with me and drunk my scotch. He is a good, honest, and truly dedicated health

care provider who really cares about his patients, and the modern American

fighting man.) Shay wrote, movingly, about the plight of men who had

experienced serious combat in Vietnam and who, as a result, had "difficulties."

He linked these stories with the stories of the Iliad and

the Odyssey, arguing that there is evidence, from his perspective

as a psychiatrist, to argue that both tales contain evidence that PTSD is a

part of the human condition. In other words, that it is a normal and

predictable byproduct of what happens when large numbers of humans are exposed

to extremes of violence. In his second book Shay was arguing for better

psychological PRE-battle training, not just for compassionate reasons (his motivation),

but for combat effectiveness (which he knew would appeal to the military). Shay

is not a trained classical historian, or a historian at all. But his books

contribute greatly to the literature and in the latter case provide at least

one decent roadmap on how we might reduce PTSD before it occurs, instead of

trying to treat it afterwards. How can that be wrong? Unfortunately, and

perhaps sadly, it appears clear that in his first book he was taken for a ride

by at least a couple of his patients at the Veterans Administration clinic

where he worked who told him tales that he was not qualified to question or

disbelieve. At least that was the contention of the other author/friend of

mine, whom I also believe.

The other, critical work on the topic of modern, or at least post-Vietnam

PTSD, is also by a man I call friend. B.G. Burkett, a former stockbroker from

Texas, was an entirely normal Vietnam vet who, by his own admission, spent an

entirely uneventful year in Vietnam doing base work. He was annoyed, then moved

to anger, by the phenomena of fake veterans who were stealing the headlines in

the 80s and 90s for their misbehavior. So, unlike many others, B.G. started

doing the hard research work to expose these fakes, expose the problems of the

media (who are supposed to be skeptical from the outset) falling for obvious

fakes, and the VA and psychiatry's complicity in expanding and enabling fakes

to claim VA benefits for combat they never saw. The end result of his 80-90 percent

useful efforts (my highest rating) was the standout self-published book, Stolen

Valor. In which, for example, B.G. convincingly exposes the fakes that

Jonathan fell for, as well as a whole host of fakes who fooled journalists and

the VA system.

It was his work

that inspired my own research techniques and methods when uncovering the

personality at the core of the No Gun Ri story, Ed Daily.

Finally, two great works which, together, give you the history of both the

psychology and the psychiatry, as well as the history, of the developing

treatments for combat veterans dealing with their memories of war.

Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely, Shell Shock to PTSD, Military Psychiatry

from 1900 to the Gulf War (Psychology Press, East Sussex, 2005)

actually dips back a little further, with accounts going back to the Crimean,

but mostly starting with the Boer War. It is a solid, if stolid, multi-national

examination, albeit with a 75 percent tilt towards diagnoses and treatment as it

related to British/Commonwealth forces. It can be a bit of heavy-going, and if

you've already read everything else on the list to this point, you could skip

this one. Alternately, just read this one and skip the others. But if you do

so, understanding will be a little thin. At least that would be the case

without the last, and best, of the lot.

Ben Shephard, A War of Nerves, Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the

Twentieth Century, (Harvard, 2001): Without a doubt one of the most

fascinating works I've read. Shephard writes in an easy, engaging, and yet

detailed "voice" on the topic of the changes, over time, to the

diagnoses applied to those "mentally softer" Tommies and Doughboys of

WWI, the weak-willed and selfish Tommies and GI's of WWII, and the Grunts of

Vietnam. (Again, to be absolutely clear, I am using these terms sarcastically,

and if you are historically astute, a tad ironically. Shephard never said such

things.) Fairly equally balanced between the U.S. and the U.K., what is really

interesting in this book is that Shephard delves into the history of the

psychiatrists themselves. How did the "DSM" (Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), first published in 1952, updated as

"DSM II" in 1968, and so on, come to be? What were the "inside

baseball" things going on within the field of psychiatry, as well as the

political implications of the actions and motivations of the most prominent

psychiatrists in, say, 1967, and how did these affect the definitions and

descriptions of the "disorder" (originally known as

"Post-Vietnam Stress Disorder" but then later, for political and

other reasons, renamed PTSD and now, again, changed to PTS or PTSS)? All

fascinating stuff, and probably your one-stop shop to learn about the answers

to all of your questions.

Hope this is

useful.

LTC Robert Bateman, has written books and

articles on military history and military theory, as well

as immeasurable amounts of snarky commentary in every outlet from Armor magazine to Parameters, from the Marine Corps Gazette to USNI Proceedings. He was once an honest infantryman, but is

now a strategist, serving in England after a recent one-year vacation

in Afghanistan.

Ignatius: To figure out where Syria is going, watch the big Sunni tribes

Who ever thought the 21st century would see us monitoring

the tribal politics of the Levant? David

Ignatius writes,

"Two big Sunni tribes,

the Shammar and the

Dulaim, stretch from northern Saudi Arabia through western Iraq and Jordan and

up into Syria. Some observers say these tribes have sworn a blood oath against

Assad. If so, a decisive phase of the Syrian war may have begun."

May 23, 2012

Kurds, oil, and Exxon

Joel Wing offers up a good

overview of Kurdish oil deals, along with some interesting maps. (I hadn't

realized, for example, that one of the blocks Exxon bought is right on the

outskirts of Mosul -- that's playing with fire.) The bottom line, it seems to

me, is that the Kurds have found a way to benefit from the dithering and

stalemates of Baghdad: They continue to talk to the central government while

acting as if they were an independent entity.

It all makes me want to sit down sometime this summer and

read Steve Coll's new

book on Exxon.

Today's odd fact: The American Revolution living into the 20th century

"The last surviving

dependent of the Revolutionary War continued to receive benefits until 1911,"

according to

a book on the Bonus March I've been reading. In other words, the last

dependent of a Revolutionary War veteran died just over 100 years ago.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers