Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 174

June 28, 2012

CSBA strategists explain how a weapon can help you win without ever being used

In a new study of strategy in an age of austerity, three CSBA authors, led by Andrew

Krepinevich, state that the B-1 bomber imposed disproportionate costs on the

Soviet military, forcing it to invest in air defenses "at the expense of

offensive capabilities, thereby pushing the superpower competition in a highly

favorable direction." Very Sun Tzu-ish!

They also argue that

given the basic resiliency of the United States, "a strategy that plays for

time or envisions the capability to contest a long-term competition appears to

be relevant today."

Another good line:

"Strategy is about taking risks and deciding what will not be done as well as

what will." This was the essence of the decisions Marshall and Eisenhower

contemplated in World War II: What was essential (keeping the Soviets in the

war, for example) vs. merely important (lots of other things).

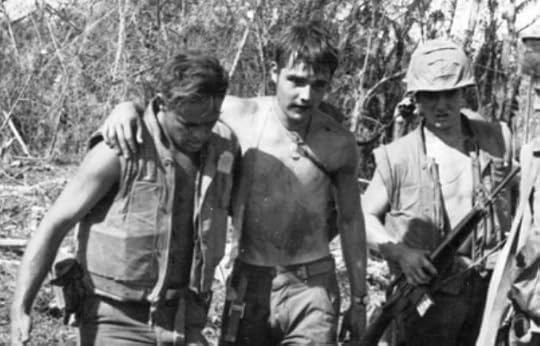

Comment of the day: How a platoon sergeant talks to his men about their loads

This was posted the other day by

"Platoon Sergeant"

in the discussion of the photo

of the two loaded American soldiers taking a break in Zabul Province:

There is something I say to my soldiers when we get ready to patrol: "You are carrying 70 pounds of the

lightest sh*t the army has ever designed. I've been in for 11 years now

and we are light years ahead of what I had when I was a private. There is still

huge areas of improvement to be made in the area of load carriage, there are a

lot of better options available off the shelf that big army wont buy. There are

some good reasons for this, as well as some bad ones. I don't know enough

about procurement to give everyone an education.

We as an army have ignored up

until recently that body armor changes how a pack interfaces with your body. Go

to any light infantry unit in the army and you will see the most commonly

personal bought item is an aftermarket assault pack. The issued assault pack is

a carry-on bag for mid-tour leave, it lacks the necessary adjustment points for

good load carriage. Some go all the way with rucksacks, I personally

bought a Kifaru Armor Grip bag, specifically designed to work with body armor

and still carry weight on your hips instead of shoulders. It was a big

investment but it paid for itself when I had to air assault 112 pounds plus

body armor and basic load in it. The molle ruck is a great pack without armor, it's

hot garbage once you put an IBA, IOTV or PC on. My unit just spent $800 dollars

from ATS for a custom designed 60 mm mortar pack for my soldiers. I can't tell

you why the army has never thought of making a pack for mortars.

The plate carrier was a great

idea for Afghanistan (personally I would wear it all the time) but we bought a

poorly designed piece of equipment. Instead of buying one with a cummerbund

that distributes the load better, we bought one that just hangs off your

shoulders. I couldn't tell you why, SOCOM has been using one with a cummerbund

for years.

The army will never get away from

carrying heavy stuff, ammo is heavy, rockets are heavy, mortars are heavy, we

could be carrying them better but we're not. The army is not concerned about your

knees or back, despite the fact that the government will be paying our

disability for the rest of our lives. I've never understood that.

(HT to WOI)

June 27, 2012

Congress and defense: Somebody finally steps up to explain how this thing works

One of the puzzlements I've had for some time is why there are so few experts on

the politics of defense, especially in the role of Congress plays. One of the few people

who genuinely has studied this subject (which is different from participating

in it) is Pat Towell,

who covered the politics of defense for decades until going upmarket and

working for the Congressional Research Service.

I mention this because I've just been reading Towell's essay

in a fairly new book, Congress and the Politics of National

Security. I covered the military for decades, but I didn't realize it

until reading the essay that the Armed

Services Committees are anomalies, having unique and far more intrusive

powers than do other committees. "The Constitution assigns Congress a degree of

authority over the organization and equipage of the armed services that has no

parallel in terms of the relationship of the legislative branch with other

executive branch agencies," he writes. "The Senate Armed Services Committees

draws particularly strong leverage from the fact that promotions for military

officers-unlike those for civil servants-require Senate confirmation."

He also makes the broader point that congressional power is

more negative than positive. "In general, it is far easier for Congress to

block a presidential initiative than to force some course of action on a

reluctant executive, simply because it is easier to mobilize a blocking

coalition."

One quibble: He says that "talented members" still seek

seats on the armed services panels. I wonder if that is still true. From what

I've seen, since the end of the Cold War, congressional leaders have been

stuffing freshman onto those committees.

I think there is a great dissertation to be done on

successful congressional interventions in the Pentagon acquisition process.

Imposing the cruise missile on a reluctant air force is one such example.

Towell touches on this in an interesting passage about air mobility and

strategic lift, but I would bet there is much more to be said.

The two times he saw his father cry

From a guest post on James Fallow's blog by Eric

McMillan, who is writing a novel about his tours of duty in Iraq, one spent

commanding a Stryker company.

"Two

years after I came home from Iraq and a year before my wife and I found out

that we were expecting a child, I stood beside my father at his mother's

funeral. He didn't cry. I didn't think that odd. I am, after all, my father's

son. I've seen him cry only two times in my entire life: When he sent me off to

war in Iraq, and when he watched me go back a second time."

Are the strategic costs of Obama's drone policy greater than the short-term gains?

By Joseph

Singh

Best

Defense department of remote-controlled warfare

The

international laws governing the use of force are fundamentally outdated,

reflecting a lost age of acutely-defined zones of war and peace, according to a

speaker at this week's panel discussion on armed drones and targeted killing.

Hosted by the German Marshall fund, the event was run under Chatham House

rules, thus none of the speakers will be identified in this post.

While

both panelists supported a convention governing drone usage, there are

convincing reasons to suspect that new international laws enacted to reflect a

changing global environment will remain wholly ineffective. Any legal framework

governing drone use will confront the perennial challenge of state behavior in

an anarchic system: Irrespective of the international laws and norms in place,

states will disregard codes of conduct if they perceive them to be contrary to

their national interests.

We know

that current international rules technically prohibit targeted killings, just

as the U.N. charter prohibits war. Even the federal government imposes its own

ban on assassinations. Issued by President Reagan, Executive Order 12333

strictly prohibits target killings, asserting that "no person employed by or

acting on behalf of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire

to engage in, assassination."

However,

the expansion of drone use under the Obama administration does not result from

a murky international laws. It simply proves that a new legal framework will

fail to chart new norms on future drone use. Give a lawyer the task of

justifying any policy "and he will find the legal regime," said one of the

panelists.

The

debate over the use of drones has often been misconstrued as a debate on the

ethics, legality and unintended consequences of using remotely piloted vehicles

to engage hostiles abroad. Yet drones have been used by nations for decades and

their specific technological attributes should not be the focus of debate.

Instead, killing by drone speaks to a larger question of defining the

conditions under which nations should deploy such force.

Panelists

noted that in Afghanistan, ISAF has been very effective at using drones as part

of the larger military campaign. Strict rules govern the use of drones under

ISAF command. Under no conditions, for example, are drones used to attack

buildings, given the possibility that unidentified civilians may be inside.

Such rigidity results not solely from a belief in abiding by the rules of war,

but from a conviction that any civilian deaths threaten greater

instability. In the hinterlands of Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen, where ground

troops are unable to help vet potential targets or engage with local populations

to redress errors, drones have struck more fear and resentment in local

populations than confidence, one panelist concluded.

One

panelist said that new norms governing drone use are necessary to ensure the

security of America and her closest allies. I am not so sure. U.S. drone

activities could hypothetically be used to justify targeting American civilians

by hostile states, but America's military dominance should always deter such

behavior. Instead, limits on the drone program are necessary for America's

strategy in the Middle East, in order to rectify the long-term trend towards

radicalization that is seeded by short-term gains in targeted killing.

In a

post-Afghanistan and post-Iraq world, the use of drones speaks to a wider

unwillingness to use large-scale, high-risk military force to project American

power abroad, as both panelists noted. Drone technology allows the president to

remain active in the fight against terrorism without having to make unpopular

and costlier "boots on the ground" commitments. Ultimately, however, the Obama administration must confront the difficult truth that what is a useful tactic

in a broader military campaign cannot be substituted for an overall strategy.

While

targeted killings constitute a centuries-old practice in international

relations, the rapid rise in drone strikes raises important questions for the

Obama administration. Are the strategic gains achieved through drone deployment

sustainable given rising public outcry over targeted killings in Pakistan,

Somalia, and Yemen? Can targeted killing programs co-exist with efforts to help

support good governance, when those programs are perceived to undermine U.S.

credibility? Will those nations continue to tacitly permit the U.S. to operate

drones in their airspace when their public condemnations prove insufficient for

satisfying domestic audiences?

In the

near term, targeted killing has crippled Al Qaeda's leadership, and may serve

as an immediate deterrent to future recruits. Yet a whack-a-mole approach to

confronting the world's largest terrorist network should not be considered an

effective long-term strategy. Incentives to change these norms will only follow

an honest assessment of the long-term strategic benefits and drawbacks of an

expansive use of drones.

June 26, 2012

The hubris of the Obamites on Vietnam: Just because you weren't there doesn't mean you won't make the same mistakes

Vietnam? What's that? Obama

administration officials ask the

estimable James Mann.

"What does that

have to do with me and the world we're living in today?" inquires Susan Rice,

American ambassador to the United Nations.

Remarks like that

worry me. Just because you weren't alive during the Vietnam War doesn't

mean you won't go down that road. I generally am a fan of the Obama administration, on both domestic and foreign policy. But the one thing that

gives me the creeps is their awkward relationship with senior military

officials. Mistrusting the Joint Chiefs, suspecting their motives, treating

them as adversaries or outsiders, not examining differences -- that was LBJ's

recipe. It didn't work. He looked upon the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a political

entity to be manipulated or, failing that, sidelined. That's a recipe for

disaster, especially for an administration conspicuously lacking interest in

the views of former military officers or even former civilian Pentagon

officials.

In our system, White House officials have the upper hand in

the civilian-military relationship, so it is their responsibility to be steward

of it. That's the price of "the

unequal dialogue." If the relationship is persistently poor, it is the

fault of the civilians, because they are in the best position to fix it. The

first step is to demand candor from the generals, and to protect those who

provide it. Remove those who don't.

Anytime anyone tells me that the lessons of Vietnam are

irrelevant, that's when I begin looking for a hole to hide in.

The soldier's load: A response from an officer in Afghanistan who is a climber

By Lt. Lucas Enloe

Best Defense guest columnist

I can definitely understand Mr.

Woods' perspective, from a number of

levels. Having carried rucks weighing upwards of

60 pounds up mountains,

I can certainly say that it sucks. I'll admit

that I haven't done any

rucking in Afghanistan yet, where it would only

suck even more. That

said, Mr. Woods' argument that applying the

philosophy of extreme

alpinism would significantly reduce soldier

loads is wrong. As an avid

alpine mountaineer myself, I can safely say that

even the extremest of

alpiners would still be forced to carry heavy

packs on extended trips.

Take, for example, an 8-day trip up and around

Mt. Rainier. Even when

climbing with some incredibly talented and

experienced mountaineers, the

average pack weight was about 65 pounds. Food

weighs a lot. And that was

operating under the convenience of being able to

melt snow to get fresh

water. Soldiers in Afghanistan don't have that

luxury.

Imagine all the food, water, and gear a hiker

would need for even a

short three-day hike. Now add a weapon, your

basic combat load of ammo,

radios, and a week's worth of batteries. And

contrary to Mr. Woods'

point, even if I was carrying no extra weight,

I'd still need a

significant amount of water, you know, because

I'm doing combat patrols

at 7,000 feet in 95 degree weather. The problem

isn't that soldiers and

NCOs are taking more than they need, the problem

is that what they need

is pretty heavy. As much as I would like to say

"Yeah, let's make our

weapons and ammo and armor and water

lighter!" I know the ridiculous

amount of time and money it would take to do

that.

Mr. Woods then argues that somehow the 60 pound

ruck is a major cause of

difficulties in counterinsurgency operations,

and then implies (I think)

that we should do without body armor or helmets.

I don't think I need to

go into more detail other than to say that I

strongly disagree.

Unfortunately Mr. Woods' lack of military

experience is the primary

reason for a large part of his argument being

infeasible.

That's not to say that all of Mr. Woods' points

are wrong. The Army has,

to an extent, recognized the need for lighter

gear in Afghanistan (see

the introduction of plate carriers, M240Ls,

etc...), but I think it can

do better. By studying the design of similar

gear in the civilian

sector, I think we can make the load easier on

our soldiers. Take, for

example, the shape and design of our rucks. If

you compare your standard

issue ruck with some large-capacity expedition

packs made by companies

like Gregory or Arcteryx (or Mystery Ranch,

whose packs I've seen

running around in Afghanistan), and you'll notice

that the Army's ruck is

much rounder, whereas the packs are narrower,

but taller. Having carried

both I can say with absolute certainty that my

civilian pack is far

superior to my issued ruck. I think that by

studying the design

philosophy of civilian mountaineering equipment

the Army can continue to

improve our gear.

Again, though, any major changes in gear take

time and money. Until

then, we'll have to continue to rely on the NCO

corps to train our

Soldiers, both physically and mentally, to deal

with the burden they'll

bear in combat. I definitely welcome any disagreements

or other

perspectives on this issue.

Lucas Enloe is an Army 1LT currently in Afghanistan. He has

years of experience in walking uphill.

Wisdom from Cairo on changes in Egypt: Keep in mind how peaceful it has been

From a report

by the International Crisis Group:

... what is most surprising, arguably, is that there has not been more violence

-- that Egyptians, by and large, have engaged in spirited debate, taken to the

streets peacefully and participated in electoral politics. Morsi's victory,

though a bitter disappointment to a large number of Egyptians, is a signal of a

continued transition. Yet all this is enormously fragile, a brittle reality at

the mercy of a single significant misstep.

June 25, 2012

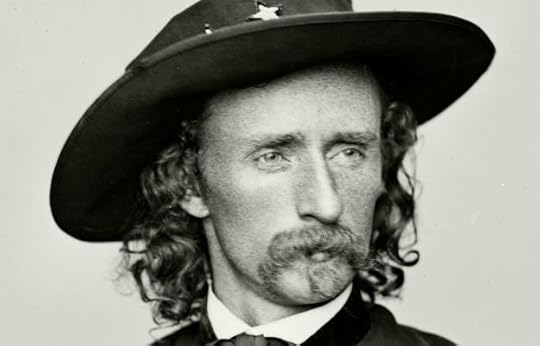

Quit picking on poor Gen. Custer, he was just following Army doctrine of his time

By "Tyrtaios"

Best Defense department of

military revisionism

In the spring of 1876, a three-pronged campaign was launched by the U.S. Army to drive the Lakota (Sioux) back

to their reservation.

The first prong, under General John Gibbon, marched east from Fort Ellis

(near Bozeman, Montana). The second prong, led by General Alfred Terry (that

also included Lieutenant Colonel George Custer), headed west from Fort Lincoln

(near Bismarck, N. Dakota), while the third prong consisted of General George

Crook's force moving up north from Wyoming into Montana.

Unknown to Terry and Gibbon, on June 17, Crook encountered a camp near the

Rosebud Creek in southern Montana, and a battle ensued lasting about six hours. Although Crook was not defeated by the standards of the day, having held

the battlefield, it demonstrated the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne would fight

long and ferociously, and must have given Crook pause, as he decided

to withdraw his force to Wyoming. This broke one side of the triangle the

three prongs were supposed to create.

Meanwhile, while Crook was retiring back into Wyoming, Terry was moving

west up the Yellowstone River to the Little Bighorn with the 7th Cavalry, with George Custer scouting up ahead in advance after leaving Terry's sight on 22

June.

On the morning of the 25th, the 7th Cavalry was at a fork between the

Rosebud and the Little Bighorn Rivers, known as the Crow's Nest, where Custer

observed another large camp. It's possible there was a haze by the time Custer came to the Crow's Nest that prevented him seeing how very large the camp actually was.

Concerned the Sioux and Cheyenne might escape, and appreciating the element of

surprise, Custer decided to attack and moved down into the valley of the Little

Bighorn. However, prior to moving, Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to

beak-off and head to the southwest with three companies to block what was seen

as a likely escape route. A few more miles from the Little Bighorn,

Custer again divided his command, ordering Major Marcus Reno to take three

companies along the river bottom and attack the village on its southern

tip, while Custer would lead the five remaining companies and follow Reno in

support.

As a side note, George Custer's two brothers, Thomas, a two-time recipient of

the Medal of Honor during the Civil War, and the youngest of the three, Boston,

were also with him.

Following the top of the ridge to an intermittent tributary of the Little

Bighorn, Custer may have finally realized the gravity of the situation as the

north end of the village came into view. We know this, and that he must

have become concerned, because he sent a message back to Benteen stating,

"Benteen, come on. Big village, be quick, bring packs, P.S. Bring packs."

The trooper Custer chose to deliver that message was bugler John Martini,

and he would be the last, with certainty, to see George Custer and his fellow

troopers alive. It is at this point that all movements by Custer and his

force are speculation, as no white survivors lived to tell the tale.

Unfortunately, Sioux and Cheyenne accounts of the battle were discounted at the time,

exacerbated probably by the Indians' fear of retribution in coming forward with

their accounts, and/or confused by language barriers, which created

inaccuracies, further complicated by fading memories as time went on.

Was George Armstrong Custer imprudent in dividing his command? Most people

with a passing familiarity with the events will immediately accuse Custer of

poor judgment, and say yes.

However, say what you will about the man's flamboyance and previous dash

toward battle, Custer was no fool in the real sense of the word, and he was a

fine cavalry commander. Some historians are reviewing his importance

at Gettysburg -- where he thwarted J.E.B. Stewart, who was coming around to support

Pickett.

One could argue Custer's tactics on June 25, 1876 were consistent with army

doctrine for that period in time, and appropriate for the situation as he at

first grasped it to be. It may be that Custer's biggest mistake was trusting

his subordinate commanders could, or even would support him as planned, and at

some early moment while the Indian attack built momentum, he must have

recognized his plan was faltering, and the luck he had been once famous for was

evaporating.

"

Tyrtaios

"

is

a retired Marine

with interest in events where quick decision

-

making might have changed

outcomes

.

What NDU looked like from the Pentagon: A big fat pain in the butt

A former Pentagon official writes:

[Y]ou probably should have mentioned that the

'real reason' everyone hates NDU is because it's where the OSD SES/seniors go

to 'hide' after their political appointments/connections expire with a change

of administration. [T]his typically happens after the election, but before the

new crowd of appointees arrive. [T]hen, from NDU, these guys thumb their noses at

the JCS and the new political appointees at OSD, and hope they can survive -- at

NDU -- until their team returns. [T]he JCS especially hates this -- and you can't

really blame them. [I]f there is any partisan difference in this practice, the

dem[ocrat]s to it way more than the rep[ublican]s do, probably because more dem[ocrat]s typically

originate from academia. [I]'ve watched this happen over the last 30 years, and

had to deal with it when I was [at OSD].

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers