Christopher Conlon's Blog, page 4

May 29, 2014

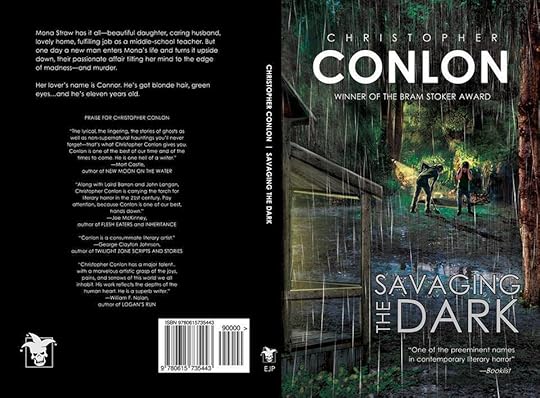

New Novel Now Available - Booklist Starred Review

http://www.amazon.com/Savaging-Dark-Christopher-Conlon-ebook/dp/B00KEZJXVS/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1401410971&sr=1-1&keywords=savaging+the+dark+conlon

Mona Straw has it all—beautiful daughter, caring husband, lovely home, fulfilling job as a middle-school teacher. But one day a new man enters Mona’s life and turns it upside down, their passionate affair tilting her mind to the edge of madness—and murder.

Her lover’s name is Connor. He’s got blonde hair, green eyes…and he’s eleven years old.

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR SAVAGING THE DARK

“If there’s a single author working in the horror genre who deserves wider notice, it might be Conlon, whose astonishing A MATRIX OF ANGELS (2011) is the most wrenching serial-killer novel of the past decade. This follow-up button-pusher would pair perfectly with Alissa Nutting’s controversial TAMPA (2013), if not for the opening scene: a terrified 11-year-old boy gagged and handcuffed to a bed while our narrator, sixth-grade English teacher Mona Straw, licks the dirt from his feet. From there, we backtrack to learn of Mona’s evolving infatuation with student Connor Blue, a kid as average and unremarkable as his teacher. Connor soon graduates from extra study lessons to yard work to an overwhelming sexual relationship, with every step utterly believable as Mona cycles through giddy elation, mordant depression, and, most of all, tortured self-justifications of her actions: ‘The top buttons are undone on the blouse but that’s because I’m just casually hanging around the house, no other reason.’ Conlon’s prose is so sturdy that Mona’s impaired viewpoint (for example, her concern that the power of their relationship is shifting to Connor) almost makes sense before it plunges them both into unavoidable disaster. Conlon writes with literary depth and commercial aplomb; his days of too-little recognition seem numbered.” — Daniel Kraus, BOOKLIST (starred review)

#

January 2, 2014

New Book for a New Year: When They Came Back, Now Available!

It’s winter 1899 in Hardgrove, Nebraska—a lonely little village in the middle of nowhere. Nothing ever happens in Hardgrove; farmers farm, shopkeepers tend to their shops, men gather at Mr. Henry’s Tavern to drink and discuss crop prices.

But things are about to change. It begins with a mysterious rain—an oily black rain that falls from peculiar green clouds and burns the skin. Then, one after another…the people return.

People who are supposed to be dead.

When They Came Back marks the first collaboration between writer Christopher Conlon, “one of the preeminent names in contemporary literary horror” (Booklist), and visionary art photographer Roberta Lannes-Sealey. It’s a story of the living dead told in words and photographs that’s unlike any you’ve ever encountered.

When They Came Back is available in trade paperback for $14.95 from BearManor Media (they also offer a .pdf, if you'd prefer):

It's also available (paperback only) from Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/When-They-Came-Christopher-Conlon/dp/1593933940/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1388694629&sr=1-1&keywords=when+they+came+back+conlon

And from Barnes & Noble:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/when-they-came-back-christopher-conlon/1117672429?ean=9781593933944

Happy new year!

#

November 29, 2013

13 for '13: A Baker's Dozen of My Favorite Reads for 2013

In some ways my list surprises me. In general I read more fiction than anything else, and I perused plenty this year—literary fiction, science fiction, some thrillers and horror—and yet when I look at the list I see that only two novels made it, and no collections of short stories at all. At the same time, my reading of poetry fell off sharply this year—yet there are three poetry titles here. And movie books feel overrepresented to me; I don’t really read that many, or at least I thought that I didn’t. Maybe I do? My list would seem to suggest so.

Anyway, in a kind of free-associational order, here’s my list of Favorite Reads of 2013.

Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 by Thomas Doherty (Columbia University Press) is an excellent study of how in the 1930s the (mostly Jewish) Hollywood moguls attempted to appease Hitler in their desire to hold onto Germany as a lucrative foreign market for their films. Doherty describes early forgotten attempts of American filmmakers to express an anti-Nazi point of view, including the fascinating-sounding I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (I’d love to find a copy of this), and details the bold efforts of Warner Brothers, the only studio to stand up against Hitler through the messages of its movies. (Confessions of a Nazi Spy was the movie that finally broke the blockade and allowed other studios to join the anti-Hitler bandwagon.) This is a fairly academic text, and not what I would call a breezy read, but it does recapture a lost bit of American cultural history. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 is certainly a must-read for students of Hollywood in the 1930s.

Henry Jaglom’s My Lunches With Orson (Metropolitan Books) provides what is in some ways the final missing piece of the puzzle that was, and still is, Orson Welles. These conversations, recorded late in Welles’s life over meals at his favorite Los Angeles restaurant, are the antithesis of the fine extended interviews collected in Peter Bogdanovich’s This Is Orson Welles, where the Great Man was very aware that he was speaking for posterity. The Jaglom volume consists of more casual encounters, and over time it appears that Welles mostly forgot he was being recorded (he insisted that the recorder be hidden). As a result we get Orson with the bark off, sharing his candid opinions of many a Hollywood figure as well as his general views on life. Since this is quite uncensored, a few of the views may strike contemporary readers as slightly racist or homophobic, but that’s the value here: This is the real Orson Welles. With this volume, together with his daughter Chris’s memoir, My Father Orson Welles, we’re finally able to get a deeper look into the private side of this most astonishingly public of men.

William Friedkin’s career has long been something of a mystery to me. Director of two of the seminal classics of ’70s cinema, The Exorcist and The French Connection, he failed to thrive in later decades, never becoming the Scorsese or Spielberg he might have been—but he has continued making movies, not flaming out and vanishing from the industry like some of his colleagues (Michael Cimino of The Deer Hunter comes to mind). In The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir (HarperCollins) the filmmaker discusses the ups and downs of his career with unusual candor, placing much of the blame for his semi-downfall squarely on his own shoulders—specifically, on his feelings of invulnerability after the twin triumphs of Exorcist and Connection. The section on his doomed follow-up to that pair of masterworks, a misbegotten remake of Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear misleadingly titled Sorcerer, is especially gripping. This is a first-rate Hollywood memoir by someone who’s seen it all, and lived to tell the tale.

I discovered Aunt Ada’s Diary: A Life in 1918 Washington, D.C. by Ada Hume Williams (edited by Bonnie Coe, published by CreateSpace) almost by accident, through a brief feature in the Style section of the Washington Post. To a longtime resident of the D.C. area and former D.C. Public Schools teacher such as myself, the book sounded intriguing. It’s the actual diary from the year 1918 of a schoolteacher who lived here. Ada Hume Williams was no great literary stylist, and the diary (written at the rate of a page a day, every day, for one year) offers little insight into Ms. Williams’s psyche. But what it does offer is an absolutely fascinating glimpse into how one working woman in her early 30s lived her life nearly a hundred years ago, in a place only a few miles from where I sit typing this. The daily detail is remarkable—she tells us what happens at school that day, what she eats, whether or not she receives a letter from her “soldier boy.” (Interestingly, Solider Boy was a former student of hers, and much younger than she—yet there is no hint that this relationship caused any kind of scandal. After the war they married.) The diarist frequently visits an elderly neighbor to read to her, in this era before radios were commonly found in people’s homes. But most of all, she goes to “plays”—by which she usually means photoplays, which we call movies. She’s enamored of a now-forgotten silent star, Jack Pickford (brother of Mary), and tells us in detail what films she sees and where. Many of the pictures she attends are now lost—I nearly started drooling when, on May 23, she reports having seen Theda Bara’s Cleopatra (“The production was splendid but I didn’t think she had any real conception of the part”). I was sufficiently intrigued by her description of Mary Pickford’s Stella Maris, in which Mary plays a dual role, that I looked it up—turns out it still exists, it’s on DVD, and Netflix has it, so of course I rented it…and it turned out to be a terrific movie, just as Mrs. Williams said it was. (I’d still rather have Cleopatra, though.) I also read two strong novels by the now-forgotten Ernest Poole, America’s first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, of whose work Mrs. Williams was also a fan. This diary provides an invaluable window into a long-lost time.

At first The Doors Unhinged by Jim Densmore (Percussive Press) may seem like a wholly unnecessary work. Twenty years ago Densmore, drummer for the 1960s rock band The Doors, penned the definitive biography of the group; titled Riders on the Storm, the book was deservedly a bestseller, and remains in print today. It’s about as good a book as any ever written about the world of rock music in that era, so what is there left to say? Plenty, as it turns out. Densmore’s new book details, depressingly, the various legal shenanigans brought to bear in his fellow band members’ attempts to wrest control of the name “the Doors” from singer Jim Morrison’s estate and Densmore himself. Much of the book is taken up with actual trial testimony, and nothing in the volume paints a pleasant picture of the other two Doors—especially late keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who is portrayed as a man completely out of touch with the original artistic vision of the group and instead focused merely on an unending hunt for ways to milk the name and music for “a few more million.” Throughout this, Densmore comes off as a likable, idealistic guy who never got the memo announcing that the values of the ’60s are now considered hopelessly naïve and passé. He’s still a believer—and that makes his account of the pathetic postscript to one of rock’s brighter legacies strangely inspiring.

In its original 1970s edition, Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection by Francis Nevins (Perfect Crime Books) was the first book of literary criticism I ever read. As a young teen I was enamored of the 1975-6 Ellery Queen TV series (still am), and it led me to the many Queen mystery novels, some of which I loved (still do). I found the Nevins book at the library—it was titled Royal Bloodline—and was immediately fascinated: a book about books? It was a new concept to me. Over three decades later Nevins has now given us this revision, and it reminds me of why I responded so strongly to the original (which I haven’t seen since the ’70s). Nevins offers the definitive overview of Ellery Queen’s career, with detailed analyses of every novel and many of the short stories and films. It’s possible to question Nevins’s critical approach at times: he has a tendency to look at the novels almost entirely as puzzles, rarely giving more than cursory consideration to such issues as style or characterization, and occasionally his judgment is so far off as to be baffling—he dismisses as a “mess” the 1930s Queen movie The Mandarin Mystery, when it’s actually a witty and delightful film. But as Francis Nevins himself taught me back in the 1970s, arguing with the critic is one of the delights of reading any book of criticism. This is without question the definitive book on Ellery Queen.

Ten years ago Gauntlet Press and editor Tony Albarella inaugurated a wildly, even recklessly ambitious publishing event: to print every single one of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone television scripts (there are ninety-two of them). The ten-volume series As Timeless as Infinity: The Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling was the result. Appearing annually, the last volume was finally published at the beginning of 2013. (Full disclosure: I helped proofread the first few of the books.) These are large-format hardcovers loaded with extras (photos, production notes, corrections in Serling’s own hand, introductions by various celebrity writers and actors)—and as a result, they’re not cheap. But for the Twilight Zone junkie, Albarella’s volumes are absolutely required reading. From early script drafts to Serling’s private correspondence, everything the TZ nut could want is here, beautifully printed and bound—further evidence of Twilight Zone’s continuing cultural relevance, more than fifty years after its premiere. Tony Albarella has performed a great service in rescuing this material from the obscurity of library collections and dusty personal files. Taken as a whole, As Timeless as Infinity may represent the greatest act of preservation ever bestowed on the written work of any program from television’s infancy.

A major publishing event this year was the appearance from Counterpoint of two volumes, New Collected Poems and This Day: Collected and New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry, which together—and they are really all one big book, hence my combining them here—comprise almost all of Berry’s poetry from his illustrious forty-year career. Many people think of Wendell Berry first as an environmental essayist or as a novelist of rural themes, but for me he is primarily a poet, and these two books confirm his status as a significant one. In a world filled with endless noise and distractions, the poems of Wendell Berry provide a quiet space for reflection and for reconnecting, if only through memory and imagination, with the natural world. His publisher’s claim that the poems represent “one of the greatest contributions ever made to American literature” is a bit much—Berry is too limited in both subject matter and technical skill to be a major poet in the sense of, say, Whitman or Dickinson—and, truth to tell, both of these books are best read in small doses: a few pages each night, say, before bed. Any more than that and the writing invariably begins to grow repetitive. That said, however, as a poet Berry does have a fundamental seriousness that’s lacking in much American verse today (or maybe it’s always been lacking?), and at his best his poems have a kind of meditative profundity—he teaches us the world, and so teaches us our own selves. In one poem, “The Silence,” Berry asks: “What must a man do to be at home in the world?” I would suggest that reading the poetry of Wendell Berry is a good place to start.

In Aimless Love: New and Selected Poems (Random House), Billy Collins proves that he still has it. The most popular American poet since Robert Frost, Collins has made a spectacular career out of his companionable, witty verses—the kind of poetry that poetry people often find suspicious, since it’s easy to understand and can be read by any reasonably literate individual without need of footnotes, essays of explanation, or an advanced degree in Literature. To read a Collins poem is to feel that you have the most agreeable possible friend at your side, a charming conversationalist who’ll keep you smiling (and sometimes laughing out loud), yet whose observations about the world can have an unexpectedly sharp bite too. I’ll confess I was dubious when I saw that one of the new poems in the book, “The Names,” was on the topic of 9/11—could the urbane Mr. Collins, whose best poems generally evoke chuckles, really address an event of that kind of seriousness? But he brings it off masterfully, creating what’s surely one of the most moving works to come out of that tragedy. (“Names lifted from a hat / Or balanced on the tip of the tongue. / Names wheeled into the dim warehouse of memory. / So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.”) I already own most of the work in this volume, but the “new poems” section is really a book unto itself, the selection is so generous (fifty-one poems, over eighty pages), and so it’s still well worth the quite reasonable purchase price. For anyone who believes that American verse has become impenetrable, incomprehensible to anyone but degreed specialists, I would say: “I agree with you, to a point—but you need to try Billy Collins.”

If Billy Collins is poetry’s version of your amiable, amusing, always-charming best friend, Franz Wright is at the exact opposite end of the spectrum: the guy you love like a brother but who will try you to your wit’s end, the guy who borrows your car and wrecks it, who never repays loans, the one who calls you in the middle of the night to talk him down from the window ledge or to bail him out of jail. In F: Poems (Knopf), Wright continues his unique poetic quest into his own psyche, giving us verse that can be both breathtakingly beautiful and breathtakingly downbeat—often in the same poem, sometimes in the same line. (The odd title of this book? Wright refers to it in one poem as his “grade in life.”) This is a writer who never shies away from discussing his own personal demons in his work, and as a result his poems can be painful to read—“Stay” opens with the lines, “The clouds were pretending to be clouds / when in fact they were overheard comments / regarding his recent behavior,” and finishes with “He could tell they were friends / by the marked improvement in their mood / when his was at its most truly desolate.” Yikes. And yet there is great power here, never more so than in the central long poem, “Entries of the Cell,” which may come to be considered Wright’s masterpiece—and in which he asserts, “the soul is a stranger in this world.” Certainly in these works Wright’s soul seems to be.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was my mother’s favorite novel—she re-read it once a year, and I can clearly remember her tattered tan-covered book club edition. Someone by Alice McDermott (FSG) limns some of the same territory of Betty Smith’s great classic, and I have a feeling Mom would have loved it. Our main character, Marie Commeford, remembers her life growing up Irish Catholic in a Brooklyn tenement. The story is told non-sequentially, and, in truth, nothing really happens—nothing exceptional, that is, nothing beyond the typical events of anyone’s life. But this is a novel which takes its strength from its precise rendering of the everyday, the quotidian. Spending time with Marie, listening to her remembrances, has the effect of making her very nearly as real as someone we know in our own lives. Here is the opening paragraph of this beautiful novel: “Pegeen Chehab walked up from the subway in the evening light. Her good spring coat was powder blue; her shoes were black and covered the insteps of her long feet. Her hat was beige with something dark along the crown, a feather or two. There was a certain asymmetry to her shoulders. She had, always, a bit of black hair along her cheek, straggling to her shoulder, her bun coming undone. She carried her purse in the lightest clasp of her fingers, down along the side of her leg, which made her seem listless and weary even as she covered the distance quickly enough, the gray sidewalk from subway to parlor floor and basement of the house next door.” This is, in essence, a one-paragraph master class in the delineation of character and environment in fiction, told with faultless word choice and rhythm. Someone was the best-written new novel I read this year.

Although some of my favorite science fiction writers published books in 2013, including Kim Stanley Robinson and Stephen Baxter, my far-and-away favorite SF novel this year was Transcendental by James Gunn (Tor). The story follows a motley group of creatures from different worlds—including a couple of humans from Earth—as they travel on the interstellar ship Geoffrey toward a mysterious planet said to house something called the Transcendental Machine. The novel itself is structured as a take on The Canterbury Tales (note the name of the ship), with each of our characters getting a chance to narrate his/her/its story in turn. Gunn’s story reminded me in some odd way of Fritz Leiber’s classic short novel The Big Time, in the sense that it’s also a galaxy-spanning tale with huge implications told in a highly intimate way, with a limited setting and very small cast of characters. The twists and turns of this saga are extremely well-handled; as for what happens when they finally reach the target world (I don’t think I’m spoiling anything to tell you that they do reach it)—well, I’ll leave it to you to find out. This novel has had a strange reception online, one which brings to mind the reception of Peter Straub’s marvelous A Dark Matter a few years ago: the professional reviews have mostly been hosannas, with many stating directly that this is surely Gunn’s masterpiece (it is), while many bloggers and customer reviewers seem baffled by the book—and take out their bafflement by writing angry, sarcastic reviews which illustrate little except for the fact that they didn’t understand it. Gunn’s novel is grown-up SF, and yes, a familiarity with The Canterbury Tales might help some readers understand why the book is put together as it is. But make no mistake: Gunn’s novel is an instant classic, one of the most powerful and profound works to come out of the SF field in a generation. That an author now in his 90s could produce such a book is an occasion for nothing but unbridled joy. Renowned SF writer and critic Paul DiFilippo says that Transcendental earns “a permanent rank in the extended canon of our genre.” He couldn’t be more right.

AND NOW (DRUM ROLL, PLEASE)…CONLON’S FAVORITE READ OF 2013…

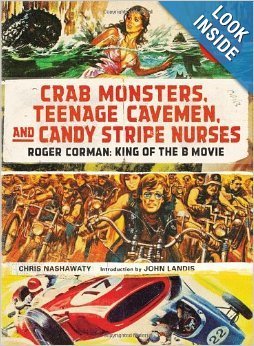

This was a really tough choice this year, and I seriously considered several books on my list for the coveted Favorite Read slot (especially Transcendental). But in the end I decided to go with the book which gave me the most simple, unalloyed delight from page to page, the greatest amount of sheer fun, and the deepest insight into something—or rather someone—I though I already knew all about.

And that book is Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses: Roger Corman, King of the B Movie by Chris Nashawaty (Abrams). This lusciously illustrated tome is more than a coffee table book, though it is that too. In 250 full-color, large-format pages editor Nashawatay gives us not only a vast visual portfolio of the career of B-movie mogul Roger Corman—everything from 1954’s Monster on the Ocean Floor to 2010’s Sharktopus, with original poster art, publicity stills, and behind-the-scenes images—but he also offers a comprehensive George Plimpton-style oral biography of the man and his movies. The interviewees, all graduates of the so-called University of Corman (having gotten their starts with him), reads like a virtual Who’s Who of Hollywood in the past fifty years: Jack Nicholson, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, Ron Howard, Dennis Hopper, Joe Dante, Pam Grier, Diane Ladd, Peter Bogdanovich, John Landis, Richard Matheson, Bruce Dern, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, Penelope Spheeris, William Shatner, Robert Towne, Sylvester Stallone…and the list, believe me, goes on.

Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful.

Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful. It’s my Favorite Read of 2013.

#

August 8, 2013

30 Years Old, Sold But Never Seen!

http://chrisconlon.livejournal.com/16395.html

But digging through a basement closet recently, I found something perhaps almost as interesting: the first story I ever sold.

How can the first story I ever sold not be the same as the first story I ever published?

Ah, therein lies a sad tale.

In the summer of 1983, after a restless, rootless period, I settled in a tiny apartment (hardly more than a closet) in San Luis Obispo, California. I had a job—I was the graveyard shift clerk at a local motel—but managed to get fired after two weeks. After that I lived on what savings I had—enough to pay the minimal rent for a few months, at least—and by selling off my belongings, especially my many LPs, which used to fetch a couple of dollars each at the local record store. (A couple of dollars could feed me for two days. I ate little but macaroni with salt and margarine.) Eventually I sold my car, or rather traded it for cash and a vastly inferior car. The exchange kept me going a while longer.

What was I doing while I was not working? I was writing.

That was the whole point. I wanted to simply write, nothing else. I’d written in elementary school, high school, and community college, but I’d never focused on it. Like lots of artistically-inclined young people, I had my hand in lots of other activities as well—music, filmmaking, theater. Eventually they all fell away, though (mostly because I discovered I had little talent for any of them). All except writing.

For eight months I lived in that little apartment in San Luis Obispo doing little but writing. I worked late, usually not starting until dark. I’d stop when it was time for The Tonight Show, which I watched with vague interest, while waiting for The David Letterman Show, which I loved. After that, bed. I slept late every day. When I got up I would generally walk downtown and spend hours in the library.

The first story I wrote during this period was called “Preparation Room.” It was November 1983; I would have been twenty-one. I proceeded to write many more stories, most of which, thankfully, ceased to exist decades ago in a great throwing-away. But “Preparation Room” I kept, not because of any particular quality it had, but because it had the distinction that it actually sold, to an honest-to-God professional editor of a real, live magazine.

It didn’t sell while I was in San Luis Obispo, though I probably sent it out once or twice. (Those used LP sales often funded the sending-out of manuscripts to editors, back in those pre-Internet days.) But a little later—specifically, in December 1984, after I’d moved to a fogbound California town called Lompoc—it did sell.

Who bought this Conlon masterwork, thus assuring himself a small place in literary history?

“Preparation Room” was purchased by a gentleman named Bill Bottiggi, editor of Tux Magazine. If you’ve never heard of Tux, well, I doubt anyone else has these days either. Tux was what was once called a “girlie” or “skin” magazine. Think Penthouse or Oui, though with far fewer pages and obviously produced on a much lower budget. Still, it was a professional publication with, naturally, lots of full-color photos throughout—photos I shan’t describe—along with, I suppose, articles of some type. You could find it in all the finest liquor stores in Lompoc, and indeed throughout the country. Tux published fiction, so I sent them “Preparation Room.”

“I read your submission with great interest,” Mr. Bottiggi responded, “and in fact would like to buy it for Tux for some future issue. I would pay $200. I’d also like to see other pieces if you’re interested; your ability to evoke that ‘frisson’ makes your fiction of the quality kind.” There was more, but those are the key sentences.

This was it, I knew—the big moment, my first sale! So it wasn’t to The New Yorker—who cared? I knew that Stephen King had gotten his start selling short stories to the girlie mags. Why not me?

I was over the moon.

But it was not to be. A few months later, having heard nothing further from Mr. Bottiggi, I received a form letter which said simply, in all caps: “PLEASE BE ADVISED THAT TUX MAGAZINE IS NO LONGER BEING PUBLISHED.” It had lasted less than a year.

No money. More importantly, no publication.

I was crushed.

I made a few more attempts to place “Preparation Room,” and oddly enough, I had some success, though on a much smaller scale. Having read in Janet Fox’s Scavenger’s Newsletter (genre writers of a certain age will remember this publication) of a new semi-prozine being launched with the wordy title Maniacs, Monsters, & the Macabre (MM&M for short), I sent in “Preparation Room.” I no longer have the documents pertaining to this, but the editor liked it and wrote that it would be appearing in his first issue alongside the works of some fairly well-known people. (One of them, I recall, was J.N. Williamson.) I don’t remember how much money I was promised, but it was probably fifteen or twenty dollars. Still—again, my first sale!

But it was also not to be. Shortly after accepting the story the editor claimed personal and financial problems, and the manuscript was returned to me. MM&M never launched at all.

During this period, however, something had begun to happen to me. Instead of imitating other pulp fiction writers, I’d begun to mine more personal aspects of myself in my fiction. Aided by my discovery of writers such as Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Carson McCullers, my stories had begun to change. They weren’t pulp fiction anymore. They were, or at least aspired to be, literary fiction, with a serious attention to style, characterization, theme. I’d lost interest in the kind of fiction I’d grown up on. Soon enough I was reading James Baldwin, William Styron, Gore Vidal, and finding a fictive world opening to me that was very different from what I’d known in Alfred Hitchcock mystery anthologies and Twilight Zone Magazine.

The first fruit of this personal reinvention was “Consummation,” a story which, for all its florid overwriting, did mark my first step on the artistic path I would ultimately travel. When it was published in 2AM in 1986, there was no turning back for me.

As a result, I lost interest in my earlier stories, which began to seem to me silly and juvenile, nothing but bad imitations of people like Richard Matheson and Robert Bloch. I threw most of them away. But I did keep a few which struck me as less terrible than the rest. I put them in a box where they still reside, decades later—a box now located in my basement.

If you’re hoping for news of any lost gems in that box, I must disappoint you. The stories are not good, and I certainly would never authorize their publication, assuming anybody would be stupid enough to want to try.

But “Preparation Room” has stayed with me. Reading it today—typing it up for this essay—I am, on the one hand, exquisitely embarrassed by it; the story really is warmed-over Robert Bloch, or someone of that ilk. As you peruse it you may find yourself perplexed that Christopher Conlon wrote it at all. It certainly doesn’t read like the work of the author of Midnight on Mourn Street or A Matrix of Angels or whatever. It has no discernible style, no underlying theme of any meaning. It’s simply a grisly little pulp tale that any modestly talented—or modestly untalented—young writer might have come up with.

Yet on the other hand I must admit that I can see why Bill Bottiggi bought, or nearly bought, this story, as did the MM&M editor. It has a certain atmosphere and narrative drive. It knows where it’s going and it gets there, it seems to me, reasonably well. You’ll notice that one of the main characters is a funeral director. I actually interviewed a funeral director in San Luis Obispo to prepare to write this story—I remember him as a heavyset man, and his office as stuffy and cluttered, but he was nice enough to give me a half-hour of his time and tell me some of the funeral industry details which appear in the story. (To make myself seem more credible I told him I was enrolled in a Creative Writing class at the local university, which wasn’t true.) It’s funny, since I would never interview someone for a purpose like that today—I’d just look up the information online. Well…

Here it is. It’s almost certainly the best story from my early, pre-literary days—which, admittedly, isn’t saying a lot. The story is juvenilia. I’ve resisted the temptation to rewrite anything; this is exactly the text which appears on those browning, stained old pages, just underneath Mr. Bottiggi’s acceptance letter and the now rusty paper clip holding everything together.

If you find “Preparation Room” terrible, well, I warned you.

If on the other hand you think it’s the best story I’ve ever written…there’s no need to tell me.

Preparation Room

Copyright ©1983 by Christopher Conlon

The figure moved in the cool semi-darkness, sometimes stopping to contemplate, sometimes smoothing the pillows, sometimes just running his hand along the edges, admiring the fine craftsmanship; sometimes smiling, sometimes dreaming. The craftsmanship, that was the thing, whether they were wood or metal; the craftsmanship.

Sometimes he would take a chair and sit here, hours after the office had closed, just sit here and watch, listen, feel, absorb the little creakings in the room, the tiny humming that passed for silence here. Absorb the cool, the quiet, the peacefulness of the place. This was a place without anxieties, without troubles, this was a place of peace, of tranquility.

But now he simply stood here, looking vaguely out the door, through the foyer, at the front window. There was a darkness coming over the valley, spreading like ink across the mountains around him, but it was not yet dark. It was twilight, his favorite time. He felt good tonight, it had been a good day. In the morning had been the Kerrs’ service, which had gone without a hitch; they had viewed the body and complimented him on a magnificent job. After that he had caught up on his paperwork, and at about two-thirty had received a death call from the hospital, about a woman named Ramsey. He had picked up the body and contacted the family; the boy waited now in the preparation room. Such a young and pretty woman, it was a tragic thing. She had had a brain tumor. He could have dealt with her today, but he hadn’t felt like it. There would be time tomorrow, plenty of time, more than enough time. She waited for him in the cold night of refrigeration, and she could wait longer; she wasn’t going anywhere.

He was lost in his thoughts to such a degree that he did not notice the figure coming up the walk, did not notice it until the door swung open and closed again with a loud snak.

A boy stood there in the foyer. Perhaps seventeen, wearing a large brown coat and blue jeans. He had a long mane of dirty blonde hair brushed back. His face was small, pinched; his eyes green, intense.

Munn stepped to the foyer. “May I help you?”

The boy looked at him. “You’re Munn.”

“That’s correct."

“We need to have a talk. Where can we talk in private?”

He looked around the foyer. “Anywhere. I’m alone here. What is the nature of your business, Mister—?”

“No names.” The boy gestured toward Munn’s office. “In there.”

“Sir, I’ll need to know the nature of…”

The boy shot him a look of knives.

Munn continued: “Are you related to the Ramseys, possibly? I understand that the deceased had a brother. Would that be you?”

He smiled. “In.”

Frowning, Munn followed the boy into the office. Grief or no, he preferred to be treated with respect. Ah well, no matter. After he left, Munn would lock the doors and go home.

He sat behind his oak desk as the boy sat in one of the visitor’s chairs. “How may I help you?”

The visitor ran his eyes around the office. “Not bad,” he said. “What’s in the closet there?”

“Sir, perhaps you’d like…”

“I mean, no kidding, what is it, a portable bar or something? Maybe a TV? What is it?”

Munn swallowed. “It’s a television set. Now, if—”

“Man, a TV, huh? Right here in your office. That’s pretty fine, you know? I bet you have a portable bar, though, don’t you? Where is it?"

“I—”

“Color?”

“The TV, man. Is it color?”

“I’m afraid that—”

“Oh, man, all I want to know is if the set’s color or not!” The boy jumped up, opened the closet door. Munn watched as he searched for the on/off switch, found it, and turned on the set. “See, man, it’s color, what d’you know? Color TV in his own office. Damn,” he said, shaking his head.

“I’ll have to ask that you…”

“What kind of stations do you get here in the valley? Probably not much, unless”—he flipped the channel selector—“damn, I knew it, cable!” He turned up the sound

.

Munn stood up, angry. “Sir, you’ll have to—”

The boy glared at him wildly. “Man, I don’t have to do nothing!”

They stared at each other. The television blared.

“What is it you want?”

He smiled a bit and a tiny, rippling giggle came from his mouth. “Just a few minutes of your time, that’s all. That’s all I want.” Munn looked at him and the boy frowned again. “And I want you to sit down and shut up.”

Munn sat, slowly.

“You got one of those video setups, too, I see, one of those Betamaxes, that’s wild. You really got time to look at those tapes?”

“Often I watch them after hours.”

“After hours,” the boy said, abruptly shutting the television off. “Song sucks, you know?” He dropped himself into the visitor’s chair again, fished in his coat pocket. “What d’you mean, ‘after hours’? How can a guy like you have after hours? People stop dying after five or what?”

“Of—course not. I’m always available by telephone. But the office here closes at five. That’s what I meant.”

“Oh, yeah, I get it.” He took out a cigarette, lit it. “Yeah, after hours, I get it.” He inhaled deeply. “Those Betamaxes, they’re great. I got one myself, you know? Tape football when I’m not home. Great, man. Expensive, though.”

Munn stared at him blankly.

“Man,” the boy continued, “I saw you in the coffin room when I came walking up. You looked like you were in seventh heaven. You got a thing about coffins or something? How much does one of those babies cost, anyway?”

“What is it you—”

With blinding speed the boy reached into his other pocket and whipped out a small dark object, slammed it down on the desk.

It was a videotape.

Munn was silent, staring at the tape.

After a moment, the boy said: “Man, I asked you a question.”

“I—”

“How much do those babies cost, man? I want to know.”

His throat was suddenly dry. He couldn’t breathe. “I—they—”

“Not the whole roll call, man, just an estimate. What’s an average one cost?”

“P-perhaps twelve to fifteen hundred dollars.” His eyes did not leave the tape.

The boy whistled. “Jesus, no kidding? That’s outrageous.”

“What is it that—”

“How do people choose them, anyway? I mean, isn’t a casket a casket? What’s the difference?”

“I…” His heart was pumping hard, much too hard. “Some—families want air tight, so they buy metal. Others prefer the…the craftsmanship—of wood.”

“Oh, yeah, I guess that’s right.” The boy stared at him, a little smile on his face. In the deepening darkness he looked vaguely sinister. He took a drag on the cigarette and dropped the ashes onto the carpet.

“What is that tape—”

“I got more questions, man, you’re interrupting me.” He leaned forward. “What d’you do with them?”

“I…what…?"

“The bodies, you know. The stiffs. What happens to them when you get them?”

“I…young man…”

“I said what happens to them!” He slammed the tape against the top of the desk.

“They…we—pick them up and contact the family, find out what’s to be done. If they’re not—not to be cremated, then we embalm them.”

There was a definite smile on the boy’s face now. “Yeah? How?”

“How—?”

“How do you embalm them, man?”

“An”—he felt sweat dripping off his underarms—“an incision. The jugular vein. As the embalming fluid is pumped in, the blood is pumped out, through the circulatory system.”

“What happens to the blood? Do you keep it?” There was a nervous, jumpy edge to his voice. An anticipation.

“No, it…it goes into the sewer system.”

“Waste of a lot of good blood. Why don’t you give it to the hospitals, man?”

He closed his eyes briefly, willing his heart to beat more slowly. “There’s…there’s too much bacteria.”

“Oh, yeah.”

“Tell me, please, what do you—”

The smile suddenly disappeared. “I’m asking the questions, man. I’m asking the questions.”

Munn sat very still, staring at the videotape.

“Where do you embalm them?”

“What—what we call the preparation room. In back.”

“Yeah? Got any stiffs there now?”

“Please…”

“I said, you got any stiffs there?”

He swallowed. “One.”

“Who?”

“A young”—he cleared his throat—“woman.”

There was silence for a moment.

“You’re a morbid dude, man,” the boy said suddenly. “I mean, how’s it go over at cocktail parties, you being a gravedigger?”

“I’m not a…”

“I bet people freak out, don’t they?”

“S…no, well—s-some.”

“Must be hard for a guy like you to make friends. I mean, who wants a guy like you for a friend, you know? We’re all going to see one of you guys anyway, sooner or later, know what I mean?”

“I—”

“So who wants to see you while they’re alive, you know?”

“Please. Please tell me why you’re here. Is it money you want?”

“Oh, man, everybody wants money.”

“Please, let me just give you…”

“Man…”

“Let me just—”

“Don’t…”

“Anything you—”

“Man, shut your frigging mouth!” The boy stood, paced the room. “Now it’s storytime. I’m going to tell you a story and you’re going to listen. You’re going to sit there, shut up, and listen.”

Munn sat quietly, watching.

“This is a story about a guy,” the boy said, “who was a fifth generation gravedigger, or funeral director, or whatever the hell you call them. Now this guy, he lived alone, see, in a little, backward town, and nobody liked him. He’d tried a couple of other towns, but he just didn’t get along with people, and it wasn’t just because he was a funeral director. Guy was weird, man. Everybody knew it. Tall, thin guy, wore glasses.”

Munn swallowed.

“Now anyway, this guy, see, he had this business, this funeral business, and he ran it all by his lonesome since the time his father died. That was like twenty years ago.” The boy paced. “Twenty years and he never had any friends, and for sure he never had a girlfriend or anything like that. Nothing, man, didn’t even own a damn goldfish. People said he was a fag, but he wasn’t. Just a lonely guy, right? Just a lonely guy trying to reach out and touch someone.” He stopped behind Munn’s desk, spoke quietly. “So, finally, he did. He touched his—customers.”

Munn’s eyes closed and the boy paced again.

“Only that wasn’t enough,” he continued. “Man needs a little enjoyment after a long hard day, so he took up the video habit. Started collecting movies, stuff like that. Bought himself a nice recorder and camera. And pretty soon, he started taking home movies.”

The boy stood at the opposite end of the room, smiled at Munn. He giggled.

“How did you—”

“Aw, never mind that, man.”

Through trembling lips Munn said, “I could take the cassette. It’s right here. I could take it, rip the tape out of it.”

“Oh, yeah,” he answered, waving his hand negligently. “Do your thing, man. I made copies.”

There was a long silence in the room. It had grown almost dark but neither of them moved to turn on a lamp. The boy lit another cigarette, his face glowing in the tiny light as he inhaled.

“What do you want?” Munn asked finally.

The boy smiled a bit, said nothing.

"How much money would it take? And how would I know that you would give me all the copies?”

He laughed a bit. “I guess you wouldn’t.”

“Then?”

He said slowly, quietly, “Maybe we can work something out.”

“What?”

The boy moved toward him, sat in the visitor’s chair. “I don’t want money,” he said flatly.

Munn looked at him. “What, then? What is it you want?”

The boy leaned forward and spoke very quietly.

“I want a piece of the action.”

Munn felt a cold finger run up his spine. “What?”

Intense eyes, burning eyes. “You heard me.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You know exactly what I’m talking about.”

He swallowed. “You’re mad.”

“Yeah? What does that make you, man?”

Munn said nothing.

The boy sat back again. “So what d’you say?”

There was a pause. Munn’s mind was blank.

“C’mon, man, cat got your tongue? What d’you say?”

Finally Munn shook the words out. “You don’t want money.”

“No, man, I got plenty of money. You know what I want.”

Munn could feel the sweat running down his sides and the darkness creeping into the room. There was a siren, somewhere far away.

“Do I have a choice?”

The boy just smiled. There was silence for a moment.

“All right,” Munn whispered.

Without words, the two of them went into the foyer, locked the front doors; then, exchanging only glances, they walked slowly back into the preparation room, the boy whispering softly, and giggling.

---

June 19, 2013

The Oblivion Room: Stories of Violation Now Available!

http://www.amazon.com/Oblivion-Room-Stories-Violation/dp/0615758185/ref=sr_1_39?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1371667995&sr=1-39&keywords=evil+jester+press

The Oblivion Room: Notes on Violation

The Oblivion Room. The grim title is, perhaps, clear enough.

But what of the subtitle—Stories of Violation?

“Violation,” according to the Random House Dictionary of the English Language, refers to “a breach, infringement, or transgression, as of law, rule, promise, etc.” The Online Etymology Dictionary further tells us that the word derives from the fifth century, the original Latin being violationem, from the past participle stem violare: “to violate, treat with violence, outrage, dishonor.” Violent, violence, violate, violation. We think of “violation” today in ways both profound and mundane: He violated me. She was violated. The language of sexual assault, rape. But, just as commonly: That traffic violation cost me fifty bucks. The everyday, the plebian. Even the tagline of a joke—at the American Music Awards Jenny McCarthy grabs and play-kisses an unsuspecting Justin Bieber, who laughs, “I feel violated right now!” A word, a concept that makes us uncomfortable, something too shocking to face directly and so it must be tamed, trivialized, deflected with humor.

Much of the world’s great literature is, at its core, about violation. Violation of trust, of loyalty, of love, of family ties. Violation of the spirit. Violation of the body. Infringement, transgression. Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, and Molly Bloom all violate their marriage vows. The Red Badge of Courage, All Quiet on the Western Front, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Johnny Got His Gun: the manifold violations of war. Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov commits murder, the ultimate violation. Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past features a vast gallery of characters engaged in violations of all types, from Charles Swann and his stalkerish pursuit of Odette (the courtesan who “wasn’t even his type”), to the sexual perversions of the proud reprobate Baron de Charlus. Jay Gatsby tries and fails to violate time itself (“Can’t repeat the past? Why, of course you can!”). Stories of the abused, the downtrodden, the persecuted are all stories of the violated: Oliver Twist, Jean Valjean, Ellison’s Invisible Man, Koestler’s Rubashov. Theater has given us the Tyrone family of Long Day’s Journey Into Night and George and Martha of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Death of a Salesman’s Willy Loman is violated by a society that treats him as disposable, while he in turn violates the trust of his wife and sons; much the same can be said of Blanche duBois, the heroine or anti-heroine of A Streetcar Named Desire, hungrily pursuing underaged schoolboys while at the same time being driven mad by the uncaring and unforgiving society around her. Even a work as seemingly anodyne as Pride and Prejudice contains as its dramatic engine the numerous violations of social protocol committed by the haughty and mysterious Mr. Darcy.

Horror fiction, more than any other kind of writing, is purely and directly about violation. Count Dracula invades England with the specific intent of instituting a reign of vampiric terror, violating the entire country (and as many unsuspecting young maidens as possible). Victor Frankenstein violates natural law in seeking to, and succeeding in, creating life from chunks of the dead; his Creature becomes another example of violator and violated in one being. Poe’s stories are filled with men who commit the most outrageous violations (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Black Cat”) as well as victims who are themselves horribly violated (“The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”). Peter Quint of James’s The Turn of the Screw (perhaps) sexually violates the boy, Miles, who is morally unhinged as a result and (perhaps) becomes a violator himself, mysteriously expelled from school for reasons never satisfactorily explained and pursued by ghosts. Modern horror stories share these same themes, from Matheson’s Scott Carey of The Shrinking Man and Blatty’s demon-possessed Regan MacNeil of The Exorcist—both violated victims—to King’s telekinetic Carrie White, another violated soul turned violator.

In its most debased form, horror fiction focuses on nothing more than violation of the body—so-called “body horror”—which, disconnected from any other meanings or resonances, can only be garish and grotesque. (Think of any slasher film ever made.) Violation of the body is an important component of horror, certainly—the genre couldn’t exist without it—but the great horror stories which utilize it do so only in pursuits of other ends. There is no example of “body horror” more memorable than the shower murder in Psycho (both Hitchcock’s film and Bloch’s novel), yet the scene exists not as an end in itself but as a means to an end. Psycho is ultimately about violations of family love and the consequences that ensue both for the surviving son and for the world outside. We remember the shower scene, yes, as a shocking and unexpected moment of terror; but what sits most deeply in our collective memories about Psycho is really the character of Norman or, in a sense more accurately, the characters of Norman and his mother—violator and violated, hopelessly and eternally entwined.

Shakespeare shows us the limitations of horror focused merely on violations of the body in Titus Andronicus, a play almost without equal in Western literature in its nearly surreal catalog of gruesome horrors (Lavinia is raped, her tongue is torn out and her hands chopped off; Titus himself cuts off one of his own hands as a ransom payment for his sons, who are killed anyway and whose severed heads are sent to his father; as for the meat pies served to Tamora, the Queen of the Goths, the less said the better). Titus Andronicus is certainly memorable, but only as the sight of a traffic accident is memorable; for all its horrific trappings, what we remember from it is merely a series of grotesqueries. On the other hand, when Lear rejects his daughter Cordelia’s expression of love, the effect is emotionally shattering both for the characters and the audience—the world itself reels, becomes unbalanced, blurs to insanity. There is far more cold, unforgettable horror in this play than in Titus, yet King Lear is never classified as “horror” at all and, in fact, features no outward appurtenances of horror other than the scene of the storm on the heath. Its horror derives from, once again, its portrayal of violation—violation deeper than the body: love’s violation—a violating parent, a violated child. In this sense at least, if in no other, there can be said to be a clear throughline from King Lear to Psycho.

The stories in The Oblivion Room all share themes of darkness, devastation, loss—the very building blocks of horror fiction, even if the standard tropes of the field are not always present. While some of the tales (“On Thursday the Stars All Fell from the Sky,” “Grace,” the title story) can obviously be classified as horror, others are really only connected to the genre through the concept of violation—violated worlds (“The Long Light of Sunday Afternoon”), violated love (“Skating the Shattered Glass Sea,” “Welcome Jean Krupa, World’s Greatest Girl Drummer!”). Yet each one has a kind of horror at its base—the sense of something too terrible to face, something that can never be trivialized or tamed.

#

May 21, 2013

The Oblivion Room - Free Giveaway!

Here's a chance to win an advance copy of The Oblivion Room and some other swag courtesy of Evil Jester Press, the book's publisher. Act now, the deadline is short. Here's the press release....

--

The winner of this giveaway will receive a free advance review copy (trade paperback format) of The Oblivion Room signed by Chris (inscribed if you wish), along with a special, unique bonus: several pages of this Bram Stoker Award-winner’s original handwritten notes and first draft of one of the stories from the collection!

“I have an unusual working method, I guess,” Chris says. “Generally I begin in longhand, with a pencil and a legal pad. I compile some very disorganized notes over a period of weeks or months, and then start into the story itself. Only after I feel that I’ve got it ‘up and running,’ so to speak, do I switch over to the computer, typing up what there is of the handwritten draft and then moving forward.” Seeing Chris’s notes and handwritten first-draft pages will provide an invaluable insight into the working processes of an author Joe McKinney calls “one of our best, hands down,” and who Gary A. Braunbeck praises as “a brilliant writer.”

To enter this giveaway, simply send an e-mail with the words “I Want to Win!” typed in the subject heading to wehsconlon[at]aol.com. No text is necessary. One entry per person. All entries must be received by Friday, May 24 2013, 5:00 pm EST. The winner will be chosen at random and notified via e-mail. Winner must respond via return e-mail with name and mailing address within 72 hours of notification or prize will be rescinded and another winner chosen.

That’s it—a free trade paperback of The Oblivion Room, hailed by Michael R. Collings of Hellnotes for its “remarkable stories” and highly recommended for readers seeking “the deeper realms of fear and terror,” along with a sheaf of handwritten notes and first-draft material from the author himself.

Enter to win today!

--

(By the way, the Hellnotes review referred to in the press release can be found here: http://hellnotes.com/the-oblivion-room-stories-of-violation-book-review)

#

April 21, 2013

Olga Klibo, 1914-2013

Voices from the past. Returned to you. And then just as suddenly stilled.

You didn’t know Olga Klibo, and that’s too bad. If you’d known her when I did, in the 1970s, and if you’d been a child too, as I was, you might have learned to love reading and books just as I did: by your weekly visits to the Buellton Library, where Mrs. Klibo was the warm, inevitable presence behind the librarian’s desk, just to the left of the front door. For a little boy like me, Mrs. Klibo didn’t “work” at the library; she was the library. Throughout my entire childhood I never once set foot in the building without her being there, and I never once saw her anywhere else. And so, as happens with kids, I was unable to imagine any other life for her. Mrs. Klibo was the library; the library was Mrs. Klibo.

Back then Buellton, California was a small, semi-rural farm town; the sign on driving in via Route 246 claimed a population of 700. (Later, when I was in high school, that sign was amended to indicate the whopping revised total of 1500.) There wasn’t a lot in Buellton other than its touristy claim to fame, which is still there: Pea Soup Andersen’s, just off Highway 101. Other than that it was a sleepy village—a couple of housing tracts (one of which contained the Conlons), a little shopping center, a restaurant or two, a few bars, an elementary school…and the library.

It didn’t even have its own building, the Buellton Library. It was just one big room within a larger structure which contained various city offices. But it was a magical place for me. My mother and I went there all the time, she for her romance novels and police procedurals, me for my science fiction and Alfred Hitchcock mystery anthologies. I remember the polished hardwood floors, the big overstuffed leather chairs, the rack of LP records that sat just to the right of the entrance. And since I’d never been in any other library in my life, it became the template for all others to follow. The Buellton Library may have been the smallest one I would ever set foot in, but I’ve never loved a library more. The reason was partly the books, of course. But mostly it was Mrs. Klibo.

She had a way about her—a way with children. While I can’t recall any specific conversations I ever had with her, I remember that she was one of the few adults in my life who took me seriously—who genuinely listened to what I said, who talked to me in a warm, attentive way that was the same way she spoke to my mother. Mrs. Klibo didn’t discriminate on account of a patron’s youth, unlike some librarians I encountered later, who often seemed to consider children a burden to have within their hallowed halls. No, Mrs. Klibo was actually interested in what I had to say: what I thought of my latest check-outs, which writers and types of writing I liked best. When I got a little older—about twelve, I think—she explained to me the miracle of library loans: that I could actually get more books by Ellery Queen and Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury than were on her shelves. All I had to do was fill out a simple little form for the book I wanted and it would arrive in a week or two. She showed me how to fill out the form, and never complained when I handed in half a dozen at a go. She knew I wasn’t wasting her time; she knew I would read the books. And I did.

I actually knew little about Mrs. Klibo, as kids generally are ignorant of the lives of the adults they see from day to day. I couldn’t have told you back then if she was married (she was), if she had children (she did), how old she was (born 1914), where she came from (Minnesota), what she did besides being a librarian (bookkeeper for her husband’s welding business, church and museum boards, PTA). All I knew was that she was a tall, plainspoken woman who made me feel welcome at a time in my life when I rarely felt welcome anywhere.

Well, times changed. My mother grew less interested in reading as she blurred into alcoholism, and when I got my driver’s license as a teenager I quickly, alas, abandoned the Buellton Library for the larger and greener book-pastures of Solvang, the next town over, and eventually to the holy grail itself: the main branch of the Santa Barbara Public Library, thirty-five miles away. The tiny Buellton Library came to seem quaint and irrelevant to me. Sometime in the later ’70s I did visit there once more, though, with my mother—I may have driven her there; she still read occasionally, at least. I can remember my shock when I walked in (I’d not been there in maybe three years, a long time at that age) and discovered a different, much younger librarian behind the desk.

“Mrs. Klibo,” she told me pleasantly, “has retired.”

It felt wrong. Terribly wrong. How could there be a Buellton Library without Mrs. Klibo in it?

I never went there again—not as any kind of statement, mind you, but rather simply because I had no reason to. My mother died, I went to college, I moved away. The usual things.

Some four years ago, in a rare fit of nostalgia, I was Googling some names from my very distant past with no real hope of finding anyone. Yet I managed to get a line on Olga Klibo who, it turned out, was still living. She was in her nineties. I couldn’t find an address for her, but eventually got in e-mail contact with her daughter, who told me Mrs. Klibo lived in a senior citizens’ home in Solvang. One thing led to another, and her daughter eventually sent me a lovely photo of Mrs. Klibo, while, on her daughter’s request, I sent a couple of my books, a photo of my mom and me, and a letter to Mrs. Klibo at the rest home.

Mrs. Klibo was unable to respond herself, but her daughter wrote me an e-mail telling me about her mother’s reaction to the package. She remembered me, all right—and I knew she was telling the truth when I was told that she recalled my mother too, quite clearly, while her memories of my father and brother (whom I’d not mentioned) were more vague. (That was exactly right; she’d certainly met them, but neither would have been a regular visitor to the library.) She was, I learned, moved to discover that I’d become a writer. The daughter closed her e-mail by thanking me for “making [her] mother’s week.”

And now Mrs. Klibo has passed on.

I can’t begin to say how happy I am that I made that final contact a few years back, that she remembered me, that she knew and understood what I’d become and the importance of the role she’d—mostly unknowingly—played in my life.

In my novel A Matrix of Angels, about two girls growing up in California in the mid-1970s, there are a couple of references to the main character, Frances, going to the local library and being helped by a certain “Mrs. Klibo.” That book wasn’t yet published when I was in touch with “my” Mrs. Klibo again, but I’m still pleased to remember the reference. Maybe a few library shelves in the world have my novel on them, and so Mrs. Klibo can live on, a little bit, in my pages.

What’s more, the Buellton Library itself now contains a children’s reading room—the Olga Klibo Children’s Reading Room.

Yes, sometimes they can knock you out—voices from the past, returned to you. And then just as suddenly stilled.

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/newspress/obituary.aspx?n=olga-eleonora-petersen-klibo&pid=162934552#fbLoggedOut

#

January 10, 2013

Coming in June from Evil Jester Press...Cover Art by Gary McCluskey!

December 15, 2012

12 for '12: My Favorite Reads of the Year

Last year around this time (December 28th, to be exact) I wrote a column about my favorite reads of 2011, bemoaning the fact that while I had indeed read some great new books that year, they seemed to have been few and far between. In fact, part of my title for that entry was “Best of a Bad Year.”

What a difference a year makes.

I don’t know what happened, but the stars aligned to make 2012 a great year for new books. I’m not the only one to think so; reviewers in both the Washington Post and the New York Times Book Review have, in the past couple of weeks, described 2012 as a banner year. The publishing industry as we’ve long known it may or may not be dying, but plenty of fantastic work appeared this year. (I can’t help pointing out a pair of possible reasons for the superiority of 2012—the fact that I had two books published: my novel Lullaby for the Rain Girl from Dark Regions and my flash fiction collection Herding Ravens from Bad Moon.)

A few notes about what follows. As always, I’ve held myself to this year’s books only; if I were to include everything else I’ve read and been impressed by this year, the list would be nearly endless. I would like to say, though, that my single favorite read of the entire year was almost certainly Mary Shelley’s astonishing, cruelly neglected masterpiece, The Last Man—the story of a plague that wipes out humanity. Published in 1826, this book was a century and a half ahead of its time. I could go on and on about it (and did, in a Goodreads review (http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/371045171).

I also enjoyed a Jack Williamson reading jag very much (especially his early space opera The Green Girl), and finally got around to reading—and loving—Armistead Maupin’s writing, especially his beautiful, suspenseful novel The Night Listener, a wonderful study of truth and falsehood and the reasons that we sometimes don’t want to let go of our most cherished illusions.

Also, bear in mind that I never make any attempt to read a representative sample of anything. What follows is simply a list of the 2012 books I liked the best, that’s all. I’m sure there are dozens of others I would have liked as well, had I managed to find them.

Finally, this list does culminate with my single Favorite Read among the books of 2012. For those of you keeping track at home, this distinguished honor has previously been bestowed on Wild Nights! by Joyce Carol Oates (2008); Endpoint and Other Poems by John Updike (2009); The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse edited by Caroline Franklin (2010); and the art book To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America featuring Ault’s work along with other artists of the ’40s and commentary by Alexander Nemerov (2011).

So, listed in (roughly) the order I read them, here are my Top 12 for ’12.

The Street Sweeper by Elliot Perlman was easily the most emotionally powerful novel of 2012 for me. This seemingly simple tale of a janitor, Lamont Williams, just out of prison and trying desperately to hold onto his probationary job at a Manhattan hospital, begins with Lamont’s newfound friendship with a patient there—a very special patient, as it turns out. The story eventually grows to include the Civil Rights Movement, the Holocaust, and a profound consideration of the humanity of us all. Despite some stilted and hard-to-believe dialogue in places, The Street Sweeper is a passionate saga which I found utterly gripping and deeply moving.

Collected Poems by Jack Gilbert was a no-brainer for me; I’ve loved Gilbert’s poetry since the 1980s, when I first discovered a closeout copy of his Monolithos at Northtown Books in Arcata, California. Gilbert, who died only weeks ago, was a giant of American poetry, yet one who lived his life mostly shunning the spotlight. If there’s any justice in the world, time will grant at least a few of Gilbert’s best works a permanent place in the pantheon of American verse. Here an early Gilbert poem (available on poemfinder.com).

Rain

Suddenly this defeat.

This rain.

The blues gone gray

and the browns gone gray

and yellow

a terrible amber.

In the cold streets

your warm body.

In whatever room

your warm body.

Among all the people

your absence.

The people who are always

not you.

I have been easy with trees

too long.

Too familiar with mountains.

Joy has been a habit.

Now

suddenly

this rain.

2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson was possibly the best science fiction novel I read this year, an engrossing story of terraforming the solar system told with the kind of believable and breathtaking scientific extrapolation Robinson does so well. As usual, the characters are far better developed than in most hard SF, and 2312 immediately earned a spot on my list of top favorite Kim Stanley Robinson novels (a list which includes the Mars Trilogy, admittedly an obvious choice, and the dark horse Antarctica).

Vlad by Carlos Fuentes. How on earth did I reach age 49 (now 50) without ever reading anything by the Mexican grandmaster Carlos Fuentes? I was intrigued by a description I saw of this short novel, so finally decided to take the Fuentes plunge—figuring that if I didn’t like it, well, at least I’d have read something by him. It turned out I loved it. Vlad is a brilliant take on the Dracula myth, reimagining Dracula in modern-day Mexico City. It’s beautifully written (even in translation), elegant, sensuous, and—in at least one particular moment—scary as hell. Vlad quickly led me to much more Fuentes: Aura, Old Gringo, The Death of Artemio Cruz, and others. His death earlier this year was a profound loss for world literature.

The Lives of Things by José Saramago is a posthumously-published collection of the great Portuguese fantasist’s early short stories, and what a collection it is. The great Saramago style is here (in translation), and the delicious uncertainty of whether we’re reading about this world or some other world. “Embargo,” a brilliant allegory involving a man whose car won’t let him leave it, is alone worth the price of the book. For those unfamiliar with the work of the man who must surely have been the greatest dark fantasist of the latter half of the 20th century (sorry, Bradbury fans), The Lives of Things will serve as a perfect introduction.

The Long Earth by Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter. No one is more surprised than I to find a Pratchett novel in my list of favorites of the year; fact is, for all his reputation as a great comedic writer, I’ve never found him funny. (I’ve found him silly. There’s a difference.) I read The Long Earth not because of Pratchett but because of his lesser-known collaborator, Stephen Baxter—who has been for many years one of my favorite hard SF writers. This novel was apparently plotted by Pratchett, and there are some Pratchettesque touches in it, but for the most part this is clearly Baxter’s book, with great speculative ideas, the main one being that there is an infinite number of “earths” which we can access by means of a “stepper”—a device powered by…a potato. (That last touch is surely Pratchett’s.) This is a terrific SF adventure story all the way.

Hiroshima Suite by William Heyen. Surely one of the most criminally underrated poets alive today, William Heyen has for decades been producing masterful verse meditations on the biggest imaginable subjects—the Holocaust (Shoah Train, a finalist for the National Book Award), the coming environmental disaster (Pterodactyl Rose), war (Ribbons), genocide (Crazy Horse in Stillness). Hiroshima Suite follows, for the most part, two people, Mr. Tanimoto, who survives the atomic blast to ferry other survivors across the Ota River, and Mrs. Aoyama, who we meet this way:

Even though in a minute or two she will cease to exist,

we are glad to know about Mrs. Aoyama.

Mrs. Aoyama happened to be pretty much exactly

right below detonation point zero in Hiroshima.

Hers was perhaps the fastest death in history…

George Bellows edited by Charles Brock is the kind of art book about which one can say little but “Wow.” Published in conjunction with a major Bellows retrospective which I saw (several times) at the National Gallery in DC, this book rescues Bellows from his position as a minor artist who created a couple of major paintings of boxers. There was far, far more to this painter who died tragically young, and this book illustrates exactly what. There is no substitute, of course, for seeing the paintings themselves, but anyone with a serious interest in American art should behold this companion volume to the show—and read the perceptive essays included, too.

Patricide by Joyce Carol Oates. Oates’s novels have blown hot and cold for me—You Must Remember This and We Were the Mulvaneys are first-rate, while others can seem rushed, insufficiently revised, even slapdash—and her short stories aren’t always memorable, though some are brilliant. I’ve long thought, however, that the novella is where Oates shines most brightly—and most consistently (witness my selection of Wild Nights! as my Favorite Read of 2008—it’s a collection of novellas). Patricide tells the story of Lou-Lou Marks, a successful academic who lives her life in the shadow of her celebrated author-father Roland. This is a superb story, with one of the most unexpected—and absolutely right—endings I’ve encountered in a long time.

In Time by C.K. Williams. This is another book by one of my long-time favorite poets, but in this case it’s a collection of essays. Williams did publish a new book of verse in 2012, Writers Writing Dying, but I didn’t care for it much—in his late-stage work Williams has taken to that worst of all poetic habits, writing poem after poem on the topic of…poetry. His essays, however, while covering various poets, also include incisive thoughts on Paris, politics, aging, and, most fascinating, a long meditation on the theme of national guilt (“Letter to a German Friend”). A first-rate mind at work. A wonderful book of essays.

Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950 edited by Joseph Goodrich unmasks the gentlemen behind “Ellery Queen,” the joint pseudonym of New York cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee. From the late ’20s to the early ’70s, Ellery Queen was one (two?) of the most popular mystery writers in the world, with sales in the hundreds of millions as well as a radio show in the ’40s, a TV show in the ’50s, lots of B-movies over lots of years, and finally a well-remembered (if short-lived) TV series in the ’70s starring Jim Hutton. Dannay and Lee’s collaboration turns out, however, to have been an extremely stormy one, as these fascinating letters prove.

AND…FINALLY…CONLON’S FAVORITE READ OF 2012…

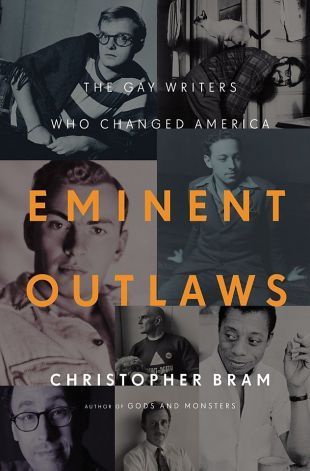

Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America by Christopher Bram. Starting with the post-World War 2 generation (Vidal, Capote, Baldwin and others) and moving through such later figures as Edward Albee, Tony Kushner, Larry Kramer, and Armistead Maupin, Christopher Bram (author of the novel Gods and Monsters) shows how gay writing in America evolved from the dark, coded coming-out stories of Capote’s time to the celebratory gay narratives of Maupin’s generation. The sections on Larry Kramer (author of the play The Normal Heart) and AIDS are especially gripping. Although I already knew much of the material in the first third of the book, Bram’s talents as a storyteller still make it seem fresh, and as I reached the later, less familiar writers, I found myself held by Bram’s sheer storytelling magic. This is a compulsively readable popular literary history which I devoured in very nearly a single sitting— and it’s not a short book.

Of course I would love to sit down with Bram and argue about some of his conclusions. He trashes what I believe is probably Tennessee Williams’s finest play, Suddenly Last Summer, as well as a flawed but fine later Baldwin novel, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone; and he comes to the eccentric conclusion that of the two movies about Truman Capote’s writing of In Cold Blood, the shallow and clichéd Infamous is superior to the magnificent Capote. But that’s part of the fun of any book of this sort—it would have made for dull reading if I’d agreed with every one of his assessments. It’s frustrating too that the book covers only the gay male writers—I found myself wishing that he also followed the narratives of the many important gay women writers of the period. Bram discusses this at the beginning, however, saying that the women really deserve their own book, and he may be correct about that—at any rate, it seems a tad unfair to criticize a book for not being something it’s not trying to be. Bram covers what he chooses to cover superbly. He is, for the most part, a first-rate critic who makes cogent arguments and, to his credit, never stints on his enthusiasms. (One of those enthusiasms is for Armistead Maupin’s books; it was Eminent Outlaws that led me to Maupin’s The Night Listener, one of my favorite non-2012 reads of the year.)

Eminent Outlaws is a book for anyone interested in the serious American fiction of the past sixty years.

It’s my Favorite Read of 2012.

#

December 9, 2012

Blood Relations: The Two Angry Halves of Ellery Queen

Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950. Edited by Joseph Goodrich. Foreword by William Link. Perfect Crime Books, 2012.

Though mostly forgotten today, Ellery Queen is vividly remembered by mystery fans of a certain age. Queen’s detective novels had a long run, from 1929’s “The Roman Hat Mystery” to 1971’s “A Fine and Private Place”’; they sold in the hundreds of millions of copies. There was a popular radio program in the ‘40s, a TV show in the ‘50s, and many B-movies over the years, including a lengthy series for Columbia starring Ralph Bellamy.