12 for '12: My Favorite Reads of the Year

Last year around this time (December 28th, to be exact) I wrote a column about my favorite reads of 2011, bemoaning the fact that while I had indeed read some great new books that year, they seemed to have been few and far between. In fact, part of my title for that entry was “Best of a Bad Year.”

What a difference a year makes.

I don’t know what happened, but the stars aligned to make 2012 a great year for new books. I’m not the only one to think so; reviewers in both the Washington Post and the New York Times Book Review have, in the past couple of weeks, described 2012 as a banner year. The publishing industry as we’ve long known it may or may not be dying, but plenty of fantastic work appeared this year. (I can’t help pointing out a pair of possible reasons for the superiority of 2012—the fact that I had two books published: my novel Lullaby for the Rain Girl from Dark Regions and my flash fiction collection Herding Ravens from Bad Moon.)

A few notes about what follows. As always, I’ve held myself to this year’s books only; if I were to include everything else I’ve read and been impressed by this year, the list would be nearly endless. I would like to say, though, that my single favorite read of the entire year was almost certainly Mary Shelley’s astonishing, cruelly neglected masterpiece, The Last Man—the story of a plague that wipes out humanity. Published in 1826, this book was a century and a half ahead of its time. I could go on and on about it (and did, in a Goodreads review (http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/371045171).

I also enjoyed a Jack Williamson reading jag very much (especially his early space opera The Green Girl), and finally got around to reading—and loving—Armistead Maupin’s writing, especially his beautiful, suspenseful novel The Night Listener, a wonderful study of truth and falsehood and the reasons that we sometimes don’t want to let go of our most cherished illusions.

Also, bear in mind that I never make any attempt to read a representative sample of anything. What follows is simply a list of the 2012 books I liked the best, that’s all. I’m sure there are dozens of others I would have liked as well, had I managed to find them.

Finally, this list does culminate with my single Favorite Read among the books of 2012. For those of you keeping track at home, this distinguished honor has previously been bestowed on Wild Nights! by Joyce Carol Oates (2008); Endpoint and Other Poems by John Updike (2009); The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse edited by Caroline Franklin (2010); and the art book To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America featuring Ault’s work along with other artists of the ’40s and commentary by Alexander Nemerov (2011).

So, listed in (roughly) the order I read them, here are my Top 12 for ’12.

The Street Sweeper by Elliot Perlman was easily the most emotionally powerful novel of 2012 for me. This seemingly simple tale of a janitor, Lamont Williams, just out of prison and trying desperately to hold onto his probationary job at a Manhattan hospital, begins with Lamont’s newfound friendship with a patient there—a very special patient, as it turns out. The story eventually grows to include the Civil Rights Movement, the Holocaust, and a profound consideration of the humanity of us all. Despite some stilted and hard-to-believe dialogue in places, The Street Sweeper is a passionate saga which I found utterly gripping and deeply moving.

Collected Poems by Jack Gilbert was a no-brainer for me; I’ve loved Gilbert’s poetry since the 1980s, when I first discovered a closeout copy of his Monolithos at Northtown Books in Arcata, California. Gilbert, who died only weeks ago, was a giant of American poetry, yet one who lived his life mostly shunning the spotlight. If there’s any justice in the world, time will grant at least a few of Gilbert’s best works a permanent place in the pantheon of American verse. Here an early Gilbert poem (available on poemfinder.com).

Rain

Suddenly this defeat.

This rain.

The blues gone gray

and the browns gone gray

and yellow

a terrible amber.

In the cold streets

your warm body.

In whatever room

your warm body.

Among all the people

your absence.

The people who are always

not you.

I have been easy with trees

too long.

Too familiar with mountains.

Joy has been a habit.

Now

suddenly

this rain.

2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson was possibly the best science fiction novel I read this year, an engrossing story of terraforming the solar system told with the kind of believable and breathtaking scientific extrapolation Robinson does so well. As usual, the characters are far better developed than in most hard SF, and 2312 immediately earned a spot on my list of top favorite Kim Stanley Robinson novels (a list which includes the Mars Trilogy, admittedly an obvious choice, and the dark horse Antarctica).

Vlad by Carlos Fuentes. How on earth did I reach age 49 (now 50) without ever reading anything by the Mexican grandmaster Carlos Fuentes? I was intrigued by a description I saw of this short novel, so finally decided to take the Fuentes plunge—figuring that if I didn’t like it, well, at least I’d have read something by him. It turned out I loved it. Vlad is a brilliant take on the Dracula myth, reimagining Dracula in modern-day Mexico City. It’s beautifully written (even in translation), elegant, sensuous, and—in at least one particular moment—scary as hell. Vlad quickly led me to much more Fuentes: Aura, Old Gringo, The Death of Artemio Cruz, and others. His death earlier this year was a profound loss for world literature.

The Lives of Things by José Saramago is a posthumously-published collection of the great Portuguese fantasist’s early short stories, and what a collection it is. The great Saramago style is here (in translation), and the delicious uncertainty of whether we’re reading about this world or some other world. “Embargo,” a brilliant allegory involving a man whose car won’t let him leave it, is alone worth the price of the book. For those unfamiliar with the work of the man who must surely have been the greatest dark fantasist of the latter half of the 20th century (sorry, Bradbury fans), The Lives of Things will serve as a perfect introduction.

The Long Earth by Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter. No one is more surprised than I to find a Pratchett novel in my list of favorites of the year; fact is, for all his reputation as a great comedic writer, I’ve never found him funny. (I’ve found him silly. There’s a difference.) I read The Long Earth not because of Pratchett but because of his lesser-known collaborator, Stephen Baxter—who has been for many years one of my favorite hard SF writers. This novel was apparently plotted by Pratchett, and there are some Pratchettesque touches in it, but for the most part this is clearly Baxter’s book, with great speculative ideas, the main one being that there is an infinite number of “earths” which we can access by means of a “stepper”—a device powered by…a potato. (That last touch is surely Pratchett’s.) This is a terrific SF adventure story all the way.

Hiroshima Suite by William Heyen. Surely one of the most criminally underrated poets alive today, William Heyen has for decades been producing masterful verse meditations on the biggest imaginable subjects—the Holocaust (Shoah Train, a finalist for the National Book Award), the coming environmental disaster (Pterodactyl Rose), war (Ribbons), genocide (Crazy Horse in Stillness). Hiroshima Suite follows, for the most part, two people, Mr. Tanimoto, who survives the atomic blast to ferry other survivors across the Ota River, and Mrs. Aoyama, who we meet this way:

Even though in a minute or two she will cease to exist,

we are glad to know about Mrs. Aoyama.

Mrs. Aoyama happened to be pretty much exactly

right below detonation point zero in Hiroshima.

Hers was perhaps the fastest death in history…

George Bellows edited by Charles Brock is the kind of art book about which one can say little but “Wow.” Published in conjunction with a major Bellows retrospective which I saw (several times) at the National Gallery in DC, this book rescues Bellows from his position as a minor artist who created a couple of major paintings of boxers. There was far, far more to this painter who died tragically young, and this book illustrates exactly what. There is no substitute, of course, for seeing the paintings themselves, but anyone with a serious interest in American art should behold this companion volume to the show—and read the perceptive essays included, too.

Patricide by Joyce Carol Oates. Oates’s novels have blown hot and cold for me—You Must Remember This and We Were the Mulvaneys are first-rate, while others can seem rushed, insufficiently revised, even slapdash—and her short stories aren’t always memorable, though some are brilliant. I’ve long thought, however, that the novella is where Oates shines most brightly—and most consistently (witness my selection of Wild Nights! as my Favorite Read of 2008—it’s a collection of novellas). Patricide tells the story of Lou-Lou Marks, a successful academic who lives her life in the shadow of her celebrated author-father Roland. This is a superb story, with one of the most unexpected—and absolutely right—endings I’ve encountered in a long time.

In Time by C.K. Williams. This is another book by one of my long-time favorite poets, but in this case it’s a collection of essays. Williams did publish a new book of verse in 2012, Writers Writing Dying, but I didn’t care for it much—in his late-stage work Williams has taken to that worst of all poetic habits, writing poem after poem on the topic of…poetry. His essays, however, while covering various poets, also include incisive thoughts on Paris, politics, aging, and, most fascinating, a long meditation on the theme of national guilt (“Letter to a German Friend”). A first-rate mind at work. A wonderful book of essays.

Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950 edited by Joseph Goodrich unmasks the gentlemen behind “Ellery Queen,” the joint pseudonym of New York cousins Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee. From the late ’20s to the early ’70s, Ellery Queen was one (two?) of the most popular mystery writers in the world, with sales in the hundreds of millions as well as a radio show in the ’40s, a TV show in the ’50s, lots of B-movies over lots of years, and finally a well-remembered (if short-lived) TV series in the ’70s starring Jim Hutton. Dannay and Lee’s collaboration turns out, however, to have been an extremely stormy one, as these fascinating letters prove.

AND…FINALLY…CONLON’S FAVORITE READ OF 2012…

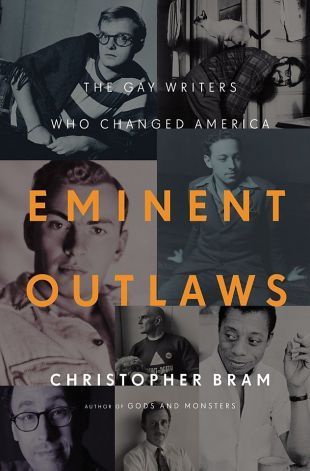

Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America by Christopher Bram. Starting with the post-World War 2 generation (Vidal, Capote, Baldwin and others) and moving through such later figures as Edward Albee, Tony Kushner, Larry Kramer, and Armistead Maupin, Christopher Bram (author of the novel Gods and Monsters) shows how gay writing in America evolved from the dark, coded coming-out stories of Capote’s time to the celebratory gay narratives of Maupin’s generation. The sections on Larry Kramer (author of the play The Normal Heart) and AIDS are especially gripping. Although I already knew much of the material in the first third of the book, Bram’s talents as a storyteller still make it seem fresh, and as I reached the later, less familiar writers, I found myself held by Bram’s sheer storytelling magic. This is a compulsively readable popular literary history which I devoured in very nearly a single sitting— and it’s not a short book.

Of course I would love to sit down with Bram and argue about some of his conclusions. He trashes what I believe is probably Tennessee Williams’s finest play, Suddenly Last Summer, as well as a flawed but fine later Baldwin novel, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone; and he comes to the eccentric conclusion that of the two movies about Truman Capote’s writing of In Cold Blood, the shallow and clichéd Infamous is superior to the magnificent Capote. But that’s part of the fun of any book of this sort—it would have made for dull reading if I’d agreed with every one of his assessments. It’s frustrating too that the book covers only the gay male writers—I found myself wishing that he also followed the narratives of the many important gay women writers of the period. Bram discusses this at the beginning, however, saying that the women really deserve their own book, and he may be correct about that—at any rate, it seems a tad unfair to criticize a book for not being something it’s not trying to be. Bram covers what he chooses to cover superbly. He is, for the most part, a first-rate critic who makes cogent arguments and, to his credit, never stints on his enthusiasms. (One of those enthusiasms is for Armistead Maupin’s books; it was Eminent Outlaws that led me to Maupin’s The Night Listener, one of my favorite non-2012 reads of the year.)

Eminent Outlaws is a book for anyone interested in the serious American fiction of the past sixty years.

It’s my Favorite Read of 2012.

#