13 for '13: A Baker's Dozen of My Favorite Reads for 2013

Book-wise, 2013 was a happy year. Not only did I have a new fiction collection released—The Oblivion Room: Stories of Violation, Evil Jester Press—but I read lots of worthwhile tomes of various types, including some brand-new 2013 releases. (I’m also counting very late 2012 releases here.) As I’ve done for the past several years, now that we’re close to year’s end I’ll list my top favorites among the new books here—with the usual disclaimer that I never make any attempt to read a representative sampling of anything. These are simply the new titles that most impressed me of the many that came under my jaded eyes in the past year. At the end of the list appears my single Favorite Read of 2013. (For the record, my previous #1 Favorite Reads have been Wild Nights! by Joyce Carol Oates [2008]; Endpoint and Other Poems by John Updike [2009]; The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse edited by Caroline Franklin [2010]; the art book To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America [2011]; and Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America by Christopher Bram [2012].)

In some ways my list surprises me. In general I read more fiction than anything else, and I perused plenty this year—literary fiction, science fiction, some thrillers and horror—and yet when I look at the list I see that only two novels made it, and no collections of short stories at all. At the same time, my reading of poetry fell off sharply this year—yet there are three poetry titles here. And movie books feel overrepresented to me; I don’t really read that many, or at least I thought that I didn’t. Maybe I do? My list would seem to suggest so.

Anyway, in a kind of free-associational order, here’s my list of Favorite Reads of 2013.

Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 by Thomas Doherty (Columbia University Press) is an excellent study of how in the 1930s the (mostly Jewish) Hollywood moguls attempted to appease Hitler in their desire to hold onto Germany as a lucrative foreign market for their films. Doherty describes early forgotten attempts of American filmmakers to express an anti-Nazi point of view, including the fascinating-sounding I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (I’d love to find a copy of this), and details the bold efforts of Warner Brothers, the only studio to stand up against Hitler through the messages of its movies. (Confessions of a Nazi Spy was the movie that finally broke the blockade and allowed other studios to join the anti-Hitler bandwagon.) This is a fairly academic text, and not what I would call a breezy read, but it does recapture a lost bit of American cultural history. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 is certainly a must-read for students of Hollywood in the 1930s.

Henry Jaglom’s My Lunches With Orson (Metropolitan Books) provides what is in some ways the final missing piece of the puzzle that was, and still is, Orson Welles. These conversations, recorded late in Welles’s life over meals at his favorite Los Angeles restaurant, are the antithesis of the fine extended interviews collected in Peter Bogdanovich’s This Is Orson Welles, where the Great Man was very aware that he was speaking for posterity. The Jaglom volume consists of more casual encounters, and over time it appears that Welles mostly forgot he was being recorded (he insisted that the recorder be hidden). As a result we get Orson with the bark off, sharing his candid opinions of many a Hollywood figure as well as his general views on life. Since this is quite uncensored, a few of the views may strike contemporary readers as slightly racist or homophobic, but that’s the value here: This is the real Orson Welles. With this volume, together with his daughter Chris’s memoir, My Father Orson Welles, we’re finally able to get a deeper look into the private side of this most astonishingly public of men.

William Friedkin’s career has long been something of a mystery to me. Director of two of the seminal classics of ’70s cinema, The Exorcist and The French Connection, he failed to thrive in later decades, never becoming the Scorsese or Spielberg he might have been—but he has continued making movies, not flaming out and vanishing from the industry like some of his colleagues (Michael Cimino of The Deer Hunter comes to mind). In The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir (HarperCollins) the filmmaker discusses the ups and downs of his career with unusual candor, placing much of the blame for his semi-downfall squarely on his own shoulders—specifically, on his feelings of invulnerability after the twin triumphs of Exorcist and Connection. The section on his doomed follow-up to that pair of masterworks, a misbegotten remake of Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear misleadingly titled Sorcerer, is especially gripping. This is a first-rate Hollywood memoir by someone who’s seen it all, and lived to tell the tale.

I discovered Aunt Ada’s Diary: A Life in 1918 Washington, D.C. by Ada Hume Williams (edited by Bonnie Coe, published by CreateSpace) almost by accident, through a brief feature in the Style section of the Washington Post. To a longtime resident of the D.C. area and former D.C. Public Schools teacher such as myself, the book sounded intriguing. It’s the actual diary from the year 1918 of a schoolteacher who lived here. Ada Hume Williams was no great literary stylist, and the diary (written at the rate of a page a day, every day, for one year) offers little insight into Ms. Williams’s psyche. But what it does offer is an absolutely fascinating glimpse into how one working woman in her early 30s lived her life nearly a hundred years ago, in a place only a few miles from where I sit typing this. The daily detail is remarkable—she tells us what happens at school that day, what she eats, whether or not she receives a letter from her “soldier boy.” (Interestingly, Solider Boy was a former student of hers, and much younger than she—yet there is no hint that this relationship caused any kind of scandal. After the war they married.) The diarist frequently visits an elderly neighbor to read to her, in this era before radios were commonly found in people’s homes. But most of all, she goes to “plays”—by which she usually means photoplays, which we call movies. She’s enamored of a now-forgotten silent star, Jack Pickford (brother of Mary), and tells us in detail what films she sees and where. Many of the pictures she attends are now lost—I nearly started drooling when, on May 23, she reports having seen Theda Bara’s Cleopatra (“The production was splendid but I didn’t think she had any real conception of the part”). I was sufficiently intrigued by her description of Mary Pickford’s Stella Maris, in which Mary plays a dual role, that I looked it up—turns out it still exists, it’s on DVD, and Netflix has it, so of course I rented it…and it turned out to be a terrific movie, just as Mrs. Williams said it was. (I’d still rather have Cleopatra, though.) I also read two strong novels by the now-forgotten Ernest Poole, America’s first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, of whose work Mrs. Williams was also a fan. This diary provides an invaluable window into a long-lost time.

At first The Doors Unhinged by Jim Densmore (Percussive Press) may seem like a wholly unnecessary work. Twenty years ago Densmore, drummer for the 1960s rock band The Doors, penned the definitive biography of the group; titled Riders on the Storm, the book was deservedly a bestseller, and remains in print today. It’s about as good a book as any ever written about the world of rock music in that era, so what is there left to say? Plenty, as it turns out. Densmore’s new book details, depressingly, the various legal shenanigans brought to bear in his fellow band members’ attempts to wrest control of the name “the Doors” from singer Jim Morrison’s estate and Densmore himself. Much of the book is taken up with actual trial testimony, and nothing in the volume paints a pleasant picture of the other two Doors—especially late keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who is portrayed as a man completely out of touch with the original artistic vision of the group and instead focused merely on an unending hunt for ways to milk the name and music for “a few more million.” Throughout this, Densmore comes off as a likable, idealistic guy who never got the memo announcing that the values of the ’60s are now considered hopelessly naïve and passé. He’s still a believer—and that makes his account of the pathetic postscript to one of rock’s brighter legacies strangely inspiring.

In its original 1970s edition, Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection by Francis Nevins (Perfect Crime Books) was the first book of literary criticism I ever read. As a young teen I was enamored of the 1975-6 Ellery Queen TV series (still am), and it led me to the many Queen mystery novels, some of which I loved (still do). I found the Nevins book at the library—it was titled Royal Bloodline—and was immediately fascinated: a book about books? It was a new concept to me. Over three decades later Nevins has now given us this revision, and it reminds me of why I responded so strongly to the original (which I haven’t seen since the ’70s). Nevins offers the definitive overview of Ellery Queen’s career, with detailed analyses of every novel and many of the short stories and films. It’s possible to question Nevins’s critical approach at times: he has a tendency to look at the novels almost entirely as puzzles, rarely giving more than cursory consideration to such issues as style or characterization, and occasionally his judgment is so far off as to be baffling—he dismisses as a “mess” the 1930s Queen movie The Mandarin Mystery, when it’s actually a witty and delightful film. But as Francis Nevins himself taught me back in the 1970s, arguing with the critic is one of the delights of reading any book of criticism. This is without question the definitive book on Ellery Queen.

Ten years ago Gauntlet Press and editor Tony Albarella inaugurated a wildly, even recklessly ambitious publishing event: to print every single one of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone television scripts (there are ninety-two of them). The ten-volume series As Timeless as Infinity: The Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling was the result. Appearing annually, the last volume was finally published at the beginning of 2013. (Full disclosure: I helped proofread the first few of the books.) These are large-format hardcovers loaded with extras (photos, production notes, corrections in Serling’s own hand, introductions by various celebrity writers and actors)—and as a result, they’re not cheap. But for the Twilight Zone junkie, Albarella’s volumes are absolutely required reading. From early script drafts to Serling’s private correspondence, everything the TZ nut could want is here, beautifully printed and bound—further evidence of Twilight Zone’s continuing cultural relevance, more than fifty years after its premiere. Tony Albarella has performed a great service in rescuing this material from the obscurity of library collections and dusty personal files. Taken as a whole, As Timeless as Infinity may represent the greatest act of preservation ever bestowed on the written work of any program from television’s infancy.

A major publishing event this year was the appearance from Counterpoint of two volumes, New Collected Poems and This Day: Collected and New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry, which together—and they are really all one big book, hence my combining them here—comprise almost all of Berry’s poetry from his illustrious forty-year career. Many people think of Wendell Berry first as an environmental essayist or as a novelist of rural themes, but for me he is primarily a poet, and these two books confirm his status as a significant one. In a world filled with endless noise and distractions, the poems of Wendell Berry provide a quiet space for reflection and for reconnecting, if only through memory and imagination, with the natural world. His publisher’s claim that the poems represent “one of the greatest contributions ever made to American literature” is a bit much—Berry is too limited in both subject matter and technical skill to be a major poet in the sense of, say, Whitman or Dickinson—and, truth to tell, both of these books are best read in small doses: a few pages each night, say, before bed. Any more than that and the writing invariably begins to grow repetitive. That said, however, as a poet Berry does have a fundamental seriousness that’s lacking in much American verse today (or maybe it’s always been lacking?), and at his best his poems have a kind of meditative profundity—he teaches us the world, and so teaches us our own selves. In one poem, “The Silence,” Berry asks: “What must a man do to be at home in the world?” I would suggest that reading the poetry of Wendell Berry is a good place to start.

In Aimless Love: New and Selected Poems (Random House), Billy Collins proves that he still has it. The most popular American poet since Robert Frost, Collins has made a spectacular career out of his companionable, witty verses—the kind of poetry that poetry people often find suspicious, since it’s easy to understand and can be read by any reasonably literate individual without need of footnotes, essays of explanation, or an advanced degree in Literature. To read a Collins poem is to feel that you have the most agreeable possible friend at your side, a charming conversationalist who’ll keep you smiling (and sometimes laughing out loud), yet whose observations about the world can have an unexpectedly sharp bite too. I’ll confess I was dubious when I saw that one of the new poems in the book, “The Names,” was on the topic of 9/11—could the urbane Mr. Collins, whose best poems generally evoke chuckles, really address an event of that kind of seriousness? But he brings it off masterfully, creating what’s surely one of the most moving works to come out of that tragedy. (“Names lifted from a hat / Or balanced on the tip of the tongue. / Names wheeled into the dim warehouse of memory. / So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.”) I already own most of the work in this volume, but the “new poems” section is really a book unto itself, the selection is so generous (fifty-one poems, over eighty pages), and so it’s still well worth the quite reasonable purchase price. For anyone who believes that American verse has become impenetrable, incomprehensible to anyone but degreed specialists, I would say: “I agree with you, to a point—but you need to try Billy Collins.”

If Billy Collins is poetry’s version of your amiable, amusing, always-charming best friend, Franz Wright is at the exact opposite end of the spectrum: the guy you love like a brother but who will try you to your wit’s end, the guy who borrows your car and wrecks it, who never repays loans, the one who calls you in the middle of the night to talk him down from the window ledge or to bail him out of jail. In F: Poems (Knopf), Wright continues his unique poetic quest into his own psyche, giving us verse that can be both breathtakingly beautiful and breathtakingly downbeat—often in the same poem, sometimes in the same line. (The odd title of this book? Wright refers to it in one poem as his “grade in life.”) This is a writer who never shies away from discussing his own personal demons in his work, and as a result his poems can be painful to read—“Stay” opens with the lines, “The clouds were pretending to be clouds / when in fact they were overheard comments / regarding his recent behavior,” and finishes with “He could tell they were friends / by the marked improvement in their mood / when his was at its most truly desolate.” Yikes. And yet there is great power here, never more so than in the central long poem, “Entries of the Cell,” which may come to be considered Wright’s masterpiece—and in which he asserts, “the soul is a stranger in this world.” Certainly in these works Wright’s soul seems to be.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was my mother’s favorite novel—she re-read it once a year, and I can clearly remember her tattered tan-covered book club edition. Someone by Alice McDermott (FSG) limns some of the same territory of Betty Smith’s great classic, and I have a feeling Mom would have loved it. Our main character, Marie Commeford, remembers her life growing up Irish Catholic in a Brooklyn tenement. The story is told non-sequentially, and, in truth, nothing really happens—nothing exceptional, that is, nothing beyond the typical events of anyone’s life. But this is a novel which takes its strength from its precise rendering of the everyday, the quotidian. Spending time with Marie, listening to her remembrances, has the effect of making her very nearly as real as someone we know in our own lives. Here is the opening paragraph of this beautiful novel: “Pegeen Chehab walked up from the subway in the evening light. Her good spring coat was powder blue; her shoes were black and covered the insteps of her long feet. Her hat was beige with something dark along the crown, a feather or two. There was a certain asymmetry to her shoulders. She had, always, a bit of black hair along her cheek, straggling to her shoulder, her bun coming undone. She carried her purse in the lightest clasp of her fingers, down along the side of her leg, which made her seem listless and weary even as she covered the distance quickly enough, the gray sidewalk from subway to parlor floor and basement of the house next door.” This is, in essence, a one-paragraph master class in the delineation of character and environment in fiction, told with faultless word choice and rhythm. Someone was the best-written new novel I read this year.

Although some of my favorite science fiction writers published books in 2013, including Kim Stanley Robinson and Stephen Baxter, my far-and-away favorite SF novel this year was Transcendental by James Gunn (Tor). The story follows a motley group of creatures from different worlds—including a couple of humans from Earth—as they travel on the interstellar ship Geoffrey toward a mysterious planet said to house something called the Transcendental Machine. The novel itself is structured as a take on The Canterbury Tales (note the name of the ship), with each of our characters getting a chance to narrate his/her/its story in turn. Gunn’s story reminded me in some odd way of Fritz Leiber’s classic short novel The Big Time, in the sense that it’s also a galaxy-spanning tale with huge implications told in a highly intimate way, with a limited setting and very small cast of characters. The twists and turns of this saga are extremely well-handled; as for what happens when they finally reach the target world (I don’t think I’m spoiling anything to tell you that they do reach it)—well, I’ll leave it to you to find out. This novel has had a strange reception online, one which brings to mind the reception of Peter Straub’s marvelous A Dark Matter a few years ago: the professional reviews have mostly been hosannas, with many stating directly that this is surely Gunn’s masterpiece (it is), while many bloggers and customer reviewers seem baffled by the book—and take out their bafflement by writing angry, sarcastic reviews which illustrate little except for the fact that they didn’t understand it. Gunn’s novel is grown-up SF, and yes, a familiarity with The Canterbury Tales might help some readers understand why the book is put together as it is. But make no mistake: Gunn’s novel is an instant classic, one of the most powerful and profound works to come out of the SF field in a generation. That an author now in his 90s could produce such a book is an occasion for nothing but unbridled joy. Renowned SF writer and critic Paul DiFilippo says that Transcendental earns “a permanent rank in the extended canon of our genre.” He couldn’t be more right.

AND NOW (DRUM ROLL, PLEASE)…CONLON’S FAVORITE READ OF 2013…

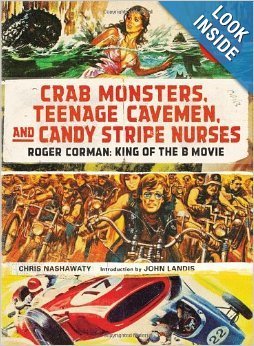

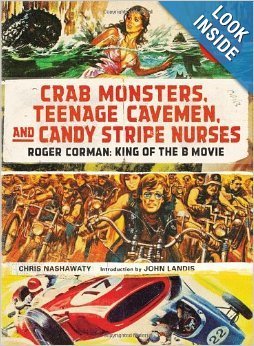

This was a really tough choice this year, and I seriously considered several books on my list for the coveted Favorite Read slot (especially Transcendental). But in the end I decided to go with the book which gave me the most simple, unalloyed delight from page to page, the greatest amount of sheer fun, and the deepest insight into something—or rather someone—I though I already knew all about.

And that book is Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses: Roger Corman, King of the B Movie by Chris Nashawaty (Abrams). This lusciously illustrated tome is more than a coffee table book, though it is that too. In 250 full-color, large-format pages editor Nashawatay gives us not only a vast visual portfolio of the career of B-movie mogul Roger Corman—everything from 1954’s Monster on the Ocean Floor to 2010’s Sharktopus, with original poster art, publicity stills, and behind-the-scenes images—but he also offers a comprehensive George Plimpton-style oral biography of the man and his movies. The interviewees, all graduates of the so-called University of Corman (having gotten their starts with him), reads like a virtual Who’s Who of Hollywood in the past fifty years: Jack Nicholson, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, Ron Howard, Dennis Hopper, Joe Dante, Pam Grier, Diane Ladd, Peter Bogdanovich, John Landis, Richard Matheson, Bruce Dern, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, Penelope Spheeris, William Shatner, Robert Towne, Sylvester Stallone…and the list, believe me, goes on. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful.

Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful.

It’s my Favorite Read of 2013.

#

In some ways my list surprises me. In general I read more fiction than anything else, and I perused plenty this year—literary fiction, science fiction, some thrillers and horror—and yet when I look at the list I see that only two novels made it, and no collections of short stories at all. At the same time, my reading of poetry fell off sharply this year—yet there are three poetry titles here. And movie books feel overrepresented to me; I don’t really read that many, or at least I thought that I didn’t. Maybe I do? My list would seem to suggest so.

Anyway, in a kind of free-associational order, here’s my list of Favorite Reads of 2013.

Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 by Thomas Doherty (Columbia University Press) is an excellent study of how in the 1930s the (mostly Jewish) Hollywood moguls attempted to appease Hitler in their desire to hold onto Germany as a lucrative foreign market for their films. Doherty describes early forgotten attempts of American filmmakers to express an anti-Nazi point of view, including the fascinating-sounding I Was a Captive of Nazi Germany (I’d love to find a copy of this), and details the bold efforts of Warner Brothers, the only studio to stand up against Hitler through the messages of its movies. (Confessions of a Nazi Spy was the movie that finally broke the blockade and allowed other studios to join the anti-Hitler bandwagon.) This is a fairly academic text, and not what I would call a breezy read, but it does recapture a lost bit of American cultural history. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 is certainly a must-read for students of Hollywood in the 1930s.

Henry Jaglom’s My Lunches With Orson (Metropolitan Books) provides what is in some ways the final missing piece of the puzzle that was, and still is, Orson Welles. These conversations, recorded late in Welles’s life over meals at his favorite Los Angeles restaurant, are the antithesis of the fine extended interviews collected in Peter Bogdanovich’s This Is Orson Welles, where the Great Man was very aware that he was speaking for posterity. The Jaglom volume consists of more casual encounters, and over time it appears that Welles mostly forgot he was being recorded (he insisted that the recorder be hidden). As a result we get Orson with the bark off, sharing his candid opinions of many a Hollywood figure as well as his general views on life. Since this is quite uncensored, a few of the views may strike contemporary readers as slightly racist or homophobic, but that’s the value here: This is the real Orson Welles. With this volume, together with his daughter Chris’s memoir, My Father Orson Welles, we’re finally able to get a deeper look into the private side of this most astonishingly public of men.

William Friedkin’s career has long been something of a mystery to me. Director of two of the seminal classics of ’70s cinema, The Exorcist and The French Connection, he failed to thrive in later decades, never becoming the Scorsese or Spielberg he might have been—but he has continued making movies, not flaming out and vanishing from the industry like some of his colleagues (Michael Cimino of The Deer Hunter comes to mind). In The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir (HarperCollins) the filmmaker discusses the ups and downs of his career with unusual candor, placing much of the blame for his semi-downfall squarely on his own shoulders—specifically, on his feelings of invulnerability after the twin triumphs of Exorcist and Connection. The section on his doomed follow-up to that pair of masterworks, a misbegotten remake of Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear misleadingly titled Sorcerer, is especially gripping. This is a first-rate Hollywood memoir by someone who’s seen it all, and lived to tell the tale.

I discovered Aunt Ada’s Diary: A Life in 1918 Washington, D.C. by Ada Hume Williams (edited by Bonnie Coe, published by CreateSpace) almost by accident, through a brief feature in the Style section of the Washington Post. To a longtime resident of the D.C. area and former D.C. Public Schools teacher such as myself, the book sounded intriguing. It’s the actual diary from the year 1918 of a schoolteacher who lived here. Ada Hume Williams was no great literary stylist, and the diary (written at the rate of a page a day, every day, for one year) offers little insight into Ms. Williams’s psyche. But what it does offer is an absolutely fascinating glimpse into how one working woman in her early 30s lived her life nearly a hundred years ago, in a place only a few miles from where I sit typing this. The daily detail is remarkable—she tells us what happens at school that day, what she eats, whether or not she receives a letter from her “soldier boy.” (Interestingly, Solider Boy was a former student of hers, and much younger than she—yet there is no hint that this relationship caused any kind of scandal. After the war they married.) The diarist frequently visits an elderly neighbor to read to her, in this era before radios were commonly found in people’s homes. But most of all, she goes to “plays”—by which she usually means photoplays, which we call movies. She’s enamored of a now-forgotten silent star, Jack Pickford (brother of Mary), and tells us in detail what films she sees and where. Many of the pictures she attends are now lost—I nearly started drooling when, on May 23, she reports having seen Theda Bara’s Cleopatra (“The production was splendid but I didn’t think she had any real conception of the part”). I was sufficiently intrigued by her description of Mary Pickford’s Stella Maris, in which Mary plays a dual role, that I looked it up—turns out it still exists, it’s on DVD, and Netflix has it, so of course I rented it…and it turned out to be a terrific movie, just as Mrs. Williams said it was. (I’d still rather have Cleopatra, though.) I also read two strong novels by the now-forgotten Ernest Poole, America’s first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, of whose work Mrs. Williams was also a fan. This diary provides an invaluable window into a long-lost time.

At first The Doors Unhinged by Jim Densmore (Percussive Press) may seem like a wholly unnecessary work. Twenty years ago Densmore, drummer for the 1960s rock band The Doors, penned the definitive biography of the group; titled Riders on the Storm, the book was deservedly a bestseller, and remains in print today. It’s about as good a book as any ever written about the world of rock music in that era, so what is there left to say? Plenty, as it turns out. Densmore’s new book details, depressingly, the various legal shenanigans brought to bear in his fellow band members’ attempts to wrest control of the name “the Doors” from singer Jim Morrison’s estate and Densmore himself. Much of the book is taken up with actual trial testimony, and nothing in the volume paints a pleasant picture of the other two Doors—especially late keyboardist Ray Manzarek, who is portrayed as a man completely out of touch with the original artistic vision of the group and instead focused merely on an unending hunt for ways to milk the name and music for “a few more million.” Throughout this, Densmore comes off as a likable, idealistic guy who never got the memo announcing that the values of the ’60s are now considered hopelessly naïve and passé. He’s still a believer—and that makes his account of the pathetic postscript to one of rock’s brighter legacies strangely inspiring.

In its original 1970s edition, Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection by Francis Nevins (Perfect Crime Books) was the first book of literary criticism I ever read. As a young teen I was enamored of the 1975-6 Ellery Queen TV series (still am), and it led me to the many Queen mystery novels, some of which I loved (still do). I found the Nevins book at the library—it was titled Royal Bloodline—and was immediately fascinated: a book about books? It was a new concept to me. Over three decades later Nevins has now given us this revision, and it reminds me of why I responded so strongly to the original (which I haven’t seen since the ’70s). Nevins offers the definitive overview of Ellery Queen’s career, with detailed analyses of every novel and many of the short stories and films. It’s possible to question Nevins’s critical approach at times: he has a tendency to look at the novels almost entirely as puzzles, rarely giving more than cursory consideration to such issues as style or characterization, and occasionally his judgment is so far off as to be baffling—he dismisses as a “mess” the 1930s Queen movie The Mandarin Mystery, when it’s actually a witty and delightful film. But as Francis Nevins himself taught me back in the 1970s, arguing with the critic is one of the delights of reading any book of criticism. This is without question the definitive book on Ellery Queen.

Ten years ago Gauntlet Press and editor Tony Albarella inaugurated a wildly, even recklessly ambitious publishing event: to print every single one of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone television scripts (there are ninety-two of them). The ten-volume series As Timeless as Infinity: The Twilight Zone Scripts of Rod Serling was the result. Appearing annually, the last volume was finally published at the beginning of 2013. (Full disclosure: I helped proofread the first few of the books.) These are large-format hardcovers loaded with extras (photos, production notes, corrections in Serling’s own hand, introductions by various celebrity writers and actors)—and as a result, they’re not cheap. But for the Twilight Zone junkie, Albarella’s volumes are absolutely required reading. From early script drafts to Serling’s private correspondence, everything the TZ nut could want is here, beautifully printed and bound—further evidence of Twilight Zone’s continuing cultural relevance, more than fifty years after its premiere. Tony Albarella has performed a great service in rescuing this material from the obscurity of library collections and dusty personal files. Taken as a whole, As Timeless as Infinity may represent the greatest act of preservation ever bestowed on the written work of any program from television’s infancy.

A major publishing event this year was the appearance from Counterpoint of two volumes, New Collected Poems and This Day: Collected and New Sabbath Poems by Wendell Berry, which together—and they are really all one big book, hence my combining them here—comprise almost all of Berry’s poetry from his illustrious forty-year career. Many people think of Wendell Berry first as an environmental essayist or as a novelist of rural themes, but for me he is primarily a poet, and these two books confirm his status as a significant one. In a world filled with endless noise and distractions, the poems of Wendell Berry provide a quiet space for reflection and for reconnecting, if only through memory and imagination, with the natural world. His publisher’s claim that the poems represent “one of the greatest contributions ever made to American literature” is a bit much—Berry is too limited in both subject matter and technical skill to be a major poet in the sense of, say, Whitman or Dickinson—and, truth to tell, both of these books are best read in small doses: a few pages each night, say, before bed. Any more than that and the writing invariably begins to grow repetitive. That said, however, as a poet Berry does have a fundamental seriousness that’s lacking in much American verse today (or maybe it’s always been lacking?), and at his best his poems have a kind of meditative profundity—he teaches us the world, and so teaches us our own selves. In one poem, “The Silence,” Berry asks: “What must a man do to be at home in the world?” I would suggest that reading the poetry of Wendell Berry is a good place to start.

In Aimless Love: New and Selected Poems (Random House), Billy Collins proves that he still has it. The most popular American poet since Robert Frost, Collins has made a spectacular career out of his companionable, witty verses—the kind of poetry that poetry people often find suspicious, since it’s easy to understand and can be read by any reasonably literate individual without need of footnotes, essays of explanation, or an advanced degree in Literature. To read a Collins poem is to feel that you have the most agreeable possible friend at your side, a charming conversationalist who’ll keep you smiling (and sometimes laughing out loud), yet whose observations about the world can have an unexpectedly sharp bite too. I’ll confess I was dubious when I saw that one of the new poems in the book, “The Names,” was on the topic of 9/11—could the urbane Mr. Collins, whose best poems generally evoke chuckles, really address an event of that kind of seriousness? But he brings it off masterfully, creating what’s surely one of the most moving works to come out of that tragedy. (“Names lifted from a hat / Or balanced on the tip of the tongue. / Names wheeled into the dim warehouse of memory. / So many names, there is barely room on the walls of the heart.”) I already own most of the work in this volume, but the “new poems” section is really a book unto itself, the selection is so generous (fifty-one poems, over eighty pages), and so it’s still well worth the quite reasonable purchase price. For anyone who believes that American verse has become impenetrable, incomprehensible to anyone but degreed specialists, I would say: “I agree with you, to a point—but you need to try Billy Collins.”

If Billy Collins is poetry’s version of your amiable, amusing, always-charming best friend, Franz Wright is at the exact opposite end of the spectrum: the guy you love like a brother but who will try you to your wit’s end, the guy who borrows your car and wrecks it, who never repays loans, the one who calls you in the middle of the night to talk him down from the window ledge or to bail him out of jail. In F: Poems (Knopf), Wright continues his unique poetic quest into his own psyche, giving us verse that can be both breathtakingly beautiful and breathtakingly downbeat—often in the same poem, sometimes in the same line. (The odd title of this book? Wright refers to it in one poem as his “grade in life.”) This is a writer who never shies away from discussing his own personal demons in his work, and as a result his poems can be painful to read—“Stay” opens with the lines, “The clouds were pretending to be clouds / when in fact they were overheard comments / regarding his recent behavior,” and finishes with “He could tell they were friends / by the marked improvement in their mood / when his was at its most truly desolate.” Yikes. And yet there is great power here, never more so than in the central long poem, “Entries of the Cell,” which may come to be considered Wright’s masterpiece—and in which he asserts, “the soul is a stranger in this world.” Certainly in these works Wright’s soul seems to be.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was my mother’s favorite novel—she re-read it once a year, and I can clearly remember her tattered tan-covered book club edition. Someone by Alice McDermott (FSG) limns some of the same territory of Betty Smith’s great classic, and I have a feeling Mom would have loved it. Our main character, Marie Commeford, remembers her life growing up Irish Catholic in a Brooklyn tenement. The story is told non-sequentially, and, in truth, nothing really happens—nothing exceptional, that is, nothing beyond the typical events of anyone’s life. But this is a novel which takes its strength from its precise rendering of the everyday, the quotidian. Spending time with Marie, listening to her remembrances, has the effect of making her very nearly as real as someone we know in our own lives. Here is the opening paragraph of this beautiful novel: “Pegeen Chehab walked up from the subway in the evening light. Her good spring coat was powder blue; her shoes were black and covered the insteps of her long feet. Her hat was beige with something dark along the crown, a feather or two. There was a certain asymmetry to her shoulders. She had, always, a bit of black hair along her cheek, straggling to her shoulder, her bun coming undone. She carried her purse in the lightest clasp of her fingers, down along the side of her leg, which made her seem listless and weary even as she covered the distance quickly enough, the gray sidewalk from subway to parlor floor and basement of the house next door.” This is, in essence, a one-paragraph master class in the delineation of character and environment in fiction, told with faultless word choice and rhythm. Someone was the best-written new novel I read this year.

Although some of my favorite science fiction writers published books in 2013, including Kim Stanley Robinson and Stephen Baxter, my far-and-away favorite SF novel this year was Transcendental by James Gunn (Tor). The story follows a motley group of creatures from different worlds—including a couple of humans from Earth—as they travel on the interstellar ship Geoffrey toward a mysterious planet said to house something called the Transcendental Machine. The novel itself is structured as a take on The Canterbury Tales (note the name of the ship), with each of our characters getting a chance to narrate his/her/its story in turn. Gunn’s story reminded me in some odd way of Fritz Leiber’s classic short novel The Big Time, in the sense that it’s also a galaxy-spanning tale with huge implications told in a highly intimate way, with a limited setting and very small cast of characters. The twists and turns of this saga are extremely well-handled; as for what happens when they finally reach the target world (I don’t think I’m spoiling anything to tell you that they do reach it)—well, I’ll leave it to you to find out. This novel has had a strange reception online, one which brings to mind the reception of Peter Straub’s marvelous A Dark Matter a few years ago: the professional reviews have mostly been hosannas, with many stating directly that this is surely Gunn’s masterpiece (it is), while many bloggers and customer reviewers seem baffled by the book—and take out their bafflement by writing angry, sarcastic reviews which illustrate little except for the fact that they didn’t understand it. Gunn’s novel is grown-up SF, and yes, a familiarity with The Canterbury Tales might help some readers understand why the book is put together as it is. But make no mistake: Gunn’s novel is an instant classic, one of the most powerful and profound works to come out of the SF field in a generation. That an author now in his 90s could produce such a book is an occasion for nothing but unbridled joy. Renowned SF writer and critic Paul DiFilippo says that Transcendental earns “a permanent rank in the extended canon of our genre.” He couldn’t be more right.

AND NOW (DRUM ROLL, PLEASE)…CONLON’S FAVORITE READ OF 2013…

This was a really tough choice this year, and I seriously considered several books on my list for the coveted Favorite Read slot (especially Transcendental). But in the end I decided to go with the book which gave me the most simple, unalloyed delight from page to page, the greatest amount of sheer fun, and the deepest insight into something—or rather someone—I though I already knew all about.

And that book is Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses: Roger Corman, King of the B Movie by Chris Nashawaty (Abrams). This lusciously illustrated tome is more than a coffee table book, though it is that too. In 250 full-color, large-format pages editor Nashawatay gives us not only a vast visual portfolio of the career of B-movie mogul Roger Corman—everything from 1954’s Monster on the Ocean Floor to 2010’s Sharktopus, with original poster art, publicity stills, and behind-the-scenes images—but he also offers a comprehensive George Plimpton-style oral biography of the man and his movies. The interviewees, all graduates of the so-called University of Corman (having gotten their starts with him), reads like a virtual Who’s Who of Hollywood in the past fifty years: Jack Nicholson, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, Ron Howard, Dennis Hopper, Joe Dante, Pam Grier, Diane Ladd, Peter Bogdanovich, John Landis, Richard Matheson, Bruce Dern, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, Penelope Spheeris, William Shatner, Robert Towne, Sylvester Stallone…and the list, believe me, goes on.

Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful.

Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses makes a case for Corman not as a great filmmaker himself—he was not, though he managed some highly memorable films from time to time (The Intruder, X—The Man With the X-Ray Eyes, the Vincent Price/Edgar Allan Poe series)—but rather as a brilliant conduit for talented people who otherwise might not have gotten their collective feet in the door of mainstream Hollywood. The stories these celebrated individuals have to tell about their former boss are always engaging, and frequently hilarious. Just as importantly, they all—every single man and woman among them—speak highly of Corman and clearly understand the role he played in their lives and careers. Director Joe Dante says, “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them.” This book collects the words of those who went on to something else and are grateful about it. Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses is a wonderful celebration of the good, the bad, and the straight-up crazy of Roger Corman’s career, and it’s a book for which every movie fan will feel grateful. It’s my Favorite Read of 2013.

#

Published on November 29, 2013 13:32

No comments have been added yet.