Christopher Conlon's Blog, page 6

December 28, 2011

The Books of 2011: Best of a Bad Year

Is it possible that I’m getting old?

Well, for another seven months or so I’ll remain on the right side of 50, but still, thinking about writing a blog on my favorite books of 2011 has made me suspect a creeping curmudgeonliness lurking within the black and bitter recesses of my heart.

Truth is, I didn’t like very much of what I read in 2011. Naturally I encountered lots of good books this year, and re-read several old favorites; but I’m talking here about new books—ones with 2011 copyright dates. For some reason it seemed an unusually weak year to me.

Now I’m not a professional book reviewer, and I never make any effort in any year to read a representative sampling of anything. For all I know, 2011 may be looked at by future generations as the greatest year in publishing history. But in terms of what I read…not so much. I did find a few outstanding titles—books I really liked—and one I loved so much it became the immediate, obvious choice for Conlon’s Favorite Book of the Year. But I felt let down by many new books, including ones by long-time favorite writers of mine.

Here are a few that come to mind.

Now in his 80s, Donald Hall brought out what was announced as his final poetry collection, The Back Chamber; while there are certainly meritorious individual poems therein, I found this slim volume to be surprisingly feeble, mostly covering familiar topics (Jane Kenyon, Eagle Pond) in ways far less memorable than what we find in his earlier work. Readers should seek out Hall’s searing verse-memoir Without, along with his greatest-hits collection White Apples and the Taste of Stone, for the best examples of this great American poet’s work.

Joyce Carol Oates, possibly the finest fiction writer this country currently has, published a collection called Give Me Your Heart: Tales of Mystery and Suspense in 2011. Oates is always worth reading, but I recall thinking that this was a lesser book from her, and looking over the Table of Contents now I see that I can actually remember only one of these stories, the erotically charged and thoroughly disturbing “Strip Poker.” Yet there are ten stories in the book. I read them all. Where did the other nine go?

In recent years I’ve become a fan of Cherie Priest’s “Clockwork Century” books, a Steampunk series that commenced with Boneshaker and continued with Dreadnought and the novella Clementine. I greatly enjoyed all of these inventive, zombie-laced bits of fanciful Victoriana—so why did Priest’s latest, Ganymede, fall so completely flat for me? It’s possible it’s not the author’s fault; in truth, I rarely read series books, and when I do, I usually check out after the second or third volume (this happened with Alexander McCall Smith’s “No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency” books, for instance). Maybe I’ve just gone to the Clockwork Century well one too many times at this point. Whatever the reasons, I must classify Ganymede as a disappointment.

Another old favorite, the great Richard Matheson, published his first novel in a long while this year, Other Kingdoms, and while it marked a considerable improvement over his previous couple of efforts, it’s undeniably a slight story—a readable little fantasy tale, nothing more. I can’t recommend it with any particular enthusiasm.

I didn’t care much for a memoir about one of my old favorites, either. Alexandra Styron’s Reading My Father focuses, of course, on her dad William Styron, author of Sophie’s Choice, Darkness Visible, and The Confessions of Nat Turner. Styron (the elder) was a formative writer for me, the quality of his prose a revelation in that period, the early ’80s, when I was transitioning from reading genre fiction to more literary work—Sophie’s Choice, in particular, was an unforgettable, transformative experience. I’m not sure how well Mr. Styron’s works will age—are aging, even now—but at least in memory, he remains a central writer of my life. His daughter, herself the author of one mildly well-received novel, seems to promise in her early pages some shocking revelations about The Great Man, but all we really get are her impressions that he could be self-absorbed (big surprise), insensitive (even bigger), and boorish (biggest of all). I was left with the thought that this memoir had no real point other than to get its author another book contract. (Memo to Alexandra Styron: My dad was way worse than yours.)

Of course I made efforts to branch out this year, as I always do, to try writers I’d never read—ones who either received rapturous reviews that caught my eye or else were recommended by friends. These writers included Madison Smartt Bell, Rachel Simon, and John R. Little, but The Color of Night, The Story of Beautiful Girl, and Ursa Major all left me disappointed. None seemed fully realized visions of what the books appeared to be trying to do, and none left me wishing to read more by their respective authors.

I read a number of new anthologies this year, mostly in genre fiction. Of these, the best was probably Jonathan Strahan’s Engineering Infinity, a gathering of (mostly) “hard” science fiction stories which features outstanding new work by Stephen Baxter, Charles Stross and others, yet which—like virtually all original anthologies—seemed to me very uneven, with too many stories that didn’t really fit into the editor’s self-described concept of the book at all.

Well, then, what did Conlon like this year?

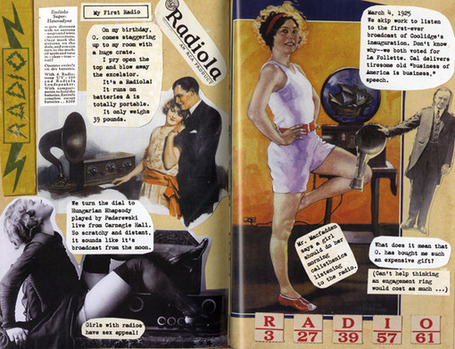

Caroline Preston’s The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt: A Novel in Pictures was pleasing. This volume follows the life of the eponymous Frankie in the 1920s, from her childhood in New Hampshire through Vassar College, Greenwich Village, and Paris. But The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt takes the form of exactly that, Frankie’s scrapbook—hundreds of vintage photos, news items, advertisements and so on, all with Frankie’s ongoing narration typed out and pasted in. The story itself isn’t much more than a straightforward period romance, and the book’s promotional materials oversell the volume as the “first-ever scrapbook novel” (it’s really just a variation on the standard graphic novel), but it’s a lot of fun—certainly a must-read for anyone interested in the 1920s. (And while you’re at it, if you’d really like to immerse yourself in the ’20s, when you go to pick up The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt at your local…er, not Borders, but maybe B & N, or an independent bookseller, why not stop by your local movie house to check out either Hugo—a pretty good movie, based on a fanciful reimagining of the life of early filmmaker George Méliès—or, even better, the transcendently wonderful The Artist, a silent-film romance of sorts set in 1920s Hollywood, and far and away Conlon’s choice for Favorite Movie of the Year?)

Anyway, moving right along: Horoscopes for the Dead by Billy Collins was my favorite book of poems this year. Collins has often been called the most popular American poet since Robert Frost, and this book reminds us why. No one I can think of in American verse today has the easy, urbane charm of Collins; no poet feels like better company. Horoscopes for the Dead is a somewhat darker book than the ones that have come before, with more concern toward aging and death, but it’s a fine volume that any poetry reader should enjoy.

Norman Prentiss, author of one of my favorites from last year—the novella Invisible Fences—returned in 2011 with Four Legs in the Morning, a suite of three stories about the mysterious and powerful Dr. Sibley, Chair of the English and Classical Literature Department at Graysonville University. These are fantasy/horror tales of a high order, filled with inventiveness and wit. I can’t say I’m a huge fan of the odd-sized edition I received (it measures roughly 5 x 9, and is just as awkward to hold in your hands as those dimensions imply—frankly, it made me long for an ebook version), but the volume is enhanced by excellent illustrations by Steven Gilberts.

I also enjoyed All the Lives He Led, the latest science fiction novel by Frederik Pohl, one of the grandmasters of the field. Now in his 90s, Pohl weaves an exciting tale here, surely his best novel in at least twenty years. In 2079 much of the United States is reeling from the dual effects of terrorism and the after-effects of a massive eruption at Yellowstone which has covered most of the western U.S. in volcanic ash and led to acid rain and crop failures worldwide. Our main character, Brad Sheridan, lives a life of petty crime on Staten Island until he escapes to Egypt and then Italy, getting a job at, of all things, a theme park at Pompeii—where he eventually becomes aware of a huge terrorist plot, one conceived on an unprecedented scale. I loved Pohl’s typically ironic tone in this book, and other than its somewhat rushed conclusion, All The Lives He Led seemed to me to fire on all cylinders.

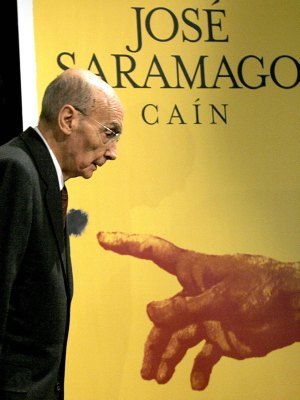

Possibly my favorite novel of 2011 was no real surprise—since falling in love with the work of the great Portuguese fantasist José Saramago a few years ago, I’ve read little by him I didn’t think was first-rate (and I’ve read nearly everything by him available in English). Cain, advertised as his final novel—Saramago died in 2010—is a wild, ribald, and thoroughly profane retelling of portions of the Bible from the point of view of the eternal wanderer himself, Cain, who encounters Noah, Job, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and other Biblical highlights, all the while arguing with God about what all of it is supposed to mean. Though Christians who lack a funny bone may have trouble with this book, I found it utterly delightful from first page to last.

As it turned out, though, my Favorite Book of 2011 was neither fiction nor poetry. (By the way, for those of you keeping score at home, my previous Favorite Book of the Year choices were Wild Nights! by Joyce Carol Oates [2008], Endpoint and Other Poems by John Updike [2009], and The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse edited by Caroline Franklin [2010].)

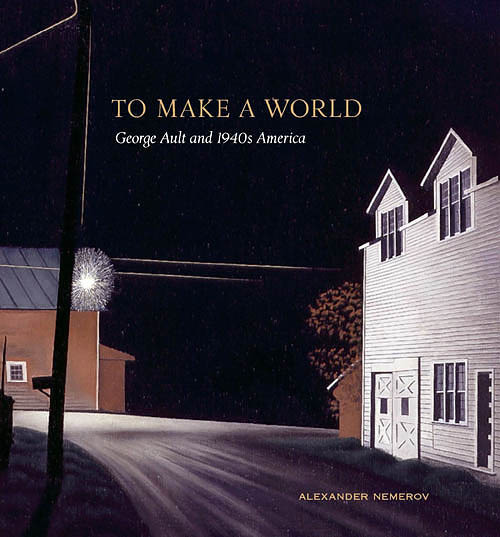

Instead, my Favorite Book of 2011 was the companion volume for my favorite exhibition of 2011, which I saw three times at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum in D.C.—To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America, by Alexander Nemerov.

Truth is, I had never even heard of George Ault before I saw a review of this exhibition in the Washington Post. This surprised me, since I tend to like American art of the mid-twentieth century (think Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth), just as I’m also fond of mid-century American music (Copland, Bernstein, Roy Harris), theater (Williams, Miller), fiction (Capote, Vidal, McCullers), poetry (Weldon Kees, Winfield Townley Scott), radio drama (Corwin, Oboler)—and, of course, movies. To Make a World—both the exhibition and the book—makes a world of a case for Ault, a relatively little-known realist painter who was born in Cleveland in 1891 but spent much of his life in New Jersey and, finally, Woodstock, New York, where he created many of his best paintings and died, apparently a suicide, in 1948. In some ways Ault’s paintings are reminiscent of Hopper’s—that same sense of isolation and alienation among the soulless structures of modern America—but Ault is more rural in orientation (and, it must be admitted, less adept at depicting the human form). His five paintings of the crossroads at Russell’s Corners in Woodstock—one is reproduced on the cover of the book—are surely his masterpieces, each with a brooding silence fully the equal of Hopper’s. To see them displayed together at the American Art Museum was a profound experience; to study them gathered in this book is only slightly less so.

But To Make a World, exhibition and book, focuses not just on Ault, but on numerous lesser-known American artists of the period as well, and I found myself moved by the canvases of Rockwell Kent, Raphael Gleitsmann (below), Kelly Fearing, and Charles Sheeler, among others. The reproductions of some of these are, alas, a bit darker than they should be, but the book still manages to effectively document and discuss the works of these numerous masterful yet half-forgotten artists. The cogently-written text by Alexander Nemerov makes all sorts of unexpected, illuminating connections.

To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America is a volume I’ve already returned to many times, and will again. It’s my Favorite Book of 2011.

Here’s to good reading in 2012....

#

December 21, 2011

A New Collection Coming

As 2011 rapidly lurches towards its end, I’m delighted to be able to say that if everything happens as it’s supposed to I will have not one, not two, but three new books out in 2012.

You already know about one, my novel Lullaby for the Rain Girl, coming from Dark Regions Press. (And if you don’t know about it, you have but to scroll down these blog entries to be enlightened.) I’m not quite ready to start talking about another, except to say that it will be a New & Selected Poems volume—more on that soon….

But today I can reveal a bit about the third. Titled Herding Ravens, it will appear in mid-2012 from Bad Moon Books, the multiple Bram Stoker Award-winning publisher of such fine genre writers as Clive Barker, Gene O’Neill, Mike Arnzen, Lisa Morton, and many more. Herding Ravens is something unique—the first-ever collection of what I call my “bon-bons,” very short, very strange little tales, usually under a thousand words each, which do things and go places my other fiction doesn’t.

What kind of story am I talking about? Rather than try to describe them, maybe I should just show you an example. Here’s one that appeared in the Dark Discoveries anthology The Bleeding Edge.

The Town Elders

copyright © Christopher Conlon

In their wisdom the town elders decreed that an ice skating rink would be built, and it was. Hundreds of happy skaters, loving couples, single men and women, teenagers, families with small wobble-walking children, came from miles around bundled in their snow clothes to enjoy gliding about on the ice under blue and white winter skies. Unfortunately the rink had been built, for reasons only the town elders might have been able to explain, over the top of a small lake, and as the weather turned from winter to spring skaters began to notice cracks which were at first no more than tiny pencil-scratches in the ice but which soon expanded to highly dangerous crevices and chasms. Skaters began to disappear under the ice into the lake, at first occasionally, and then on an alarmingly regular basis.

When blossoms began opening all over town and the weather had turned the warm of sandals and shorts, the ice rink was dismantled entirely and the same persons who had enjoyed the winter skating, that is, those who still survived, came to the lake, disrobing almost completely and allowing the sun to bronze their skin for hours on end. They ate from picnic baskets and cooked hamburgers on small barbeques. Many of them swam delightedly in the lake, paddling this way and that and playfully splashing each other. One problem, which the town elders failed entirely to solve, was that at times corpses left over from the fiasco of the skating rink would suddenly surface, and at the most inopportune times. It became an embarrassment and something of a public relations problem, never more so than when a young woman dragged a male corpse to shore, proclaiming it to be what remained of her first and indeed only true love, thereupon carrying the disintegrating thing over her shoulders to the local courthouse where she demanded that the town elders allow her to marry it. She was informed that the law did not allow for the marriage of woman to corpse, and this created a small but similarly embarrassing civil rights kerfuffle. The woman ultimately decided to cohabitate with her dearly beloved, a decision which generated some controversy in itself—but not, the town elders were certain, on the level that would have occurred had they allowed the two of them to enter into the state of holy matrimony.

One odd aspect to this entire problem of the corpses in the lake was that the lake never seemed to tire of disgorging corpses onto the shore. After a time it became embarrassingly apparent that far more deceased persons were washing up onto the sands than had vanished from the ice rink during the winter. The town elders formed a committee to study this apparently impossible problem, but no final report from this committee is known to have been issued, or if issued, it appears to have been lost.

In the meantime winter came again and the lake was once more crusted over with smooth, inviting ice. Again came the young lovers and the men and women and the families with their small wobble-walking children. But now some noticed odd round bumps appearing on the surface of the ice, bumps which slowly split the ice in places through which strange things, at first unrecognizable, began to grow. Some persons believed that the growths might be some new strain of cauliflower or tomato, but soon enough it became apparent that the growths were in fact human beings. One would see the clear ice-encrusted outlines of a forehead, a temple, a set of ears, frost-filled strands of hair. This for the town elders was the ultimate humiliation, and it was quickly decided that something would have to be done. Fortunately there was a course of action readily and even obviously available to them, and they took it. The town elders began to cultivate this unprecedented winter crop. One would see them late at night in their heavy coats tilling the ice rink with shovels and hoes, always careful to smooth the ice again after pulling nature’s peculiar yield from the ice. Eventually the story, which was true, went around that the crops were in fact delicious to eat when prepared properly, and soon the townspeople themselves were tending what was now less a skating rink than a glorious winter garden. Neighbors laughed and joked about this unexpected bounty and exchanged recipes enthusiastically. If you ever decide to go to the town, by all means do so in the depths of winter. Buy one of the readily-available cookbooks for sale at various shops near the garden. And then go and collect some winter crops for your own dinner. There’s more than enough for everyone. Indeed, the supply is ample and even, at times, overwhelming. The heads of teenage girls are said to be especially succulent when stewed for several hours with carrot and onion in chicken stock. Or snap off some baby fingers, which are simple to gather and requite no preparation at all. The town elders assure us that they are delicious straight from the ice, sweet and with an unexpected tanginess.

----

A handful of my bon-bons have been published here and there, but the vast majority of them have never been seen anyplace—making Herding Ravens an almost all-new collection of my fiction, a collection totally unlike my previous ones.

But what really excites me about Herding Ravens is that Bad Moon has commissioned a wonderful artist, Daryl Earnest, to provide an illustration for every story—some 26 in all. Here’s his rendering (not done specifically for my book) of a certain gentleman whose spirit looms large over the stories in the collection.

I was lucky enough to be able to briefly interview Daryl just after he received news that he would be doing the art for Herding Ravens. Here’s our exchange:

CC: Daryl, what is your background in art, and how does that connect to your interest in horror and fantasy fiction?

DE: I have just your standard school art education, just to high school and no further. This is probably unique to me, but I didn't do well in the structured classes I was a part of; I spent most of my time rebelling against the whole concept of "to be artistic, you have to draw the same still-life, use the same colors,” etc. I suppose I drove my teachers as crazy as they drove me!

I was just always drawn to the horror/dark fantasy side, probably because I was a Bernie Wrightson FREAK as a kid...still am, for that matter; it's just now I've had a chance to see more and develop more influences, people like Franklin Booth and Virgil Finlay, and many more. Plus, one of the earliest books I ever remember reading was Stephen King's The Stand;I was obviously WAY too young to fully understand it, but I loved what I DID get...plus, it had some great Wrightson art! And lastly, I can't forget those great old Weird Tales and EC comics reprints I got my hands on..."A little irony's good for the blood", indeed….

CC: You've mentioned to me that you've wanted to break into book illustration for a long time. Can you talk about that?

DE: Again, this goes back to when I was growing up, but you always want to do what you love, and I always loved those WILD panels and covers I saw in the books I read; to the point that I made up my mind one day that I'm good enough to do this...and here we are!

CC: How do you do your work as an artist? What's the process from the start to the finished piece?

DE: I guess that since I'm not "formally" trained, I probably have a pretty unorthodox approach to my work. Basically, when I get an idea, I grab a stray piece of paper and scribble something somewhat rough out, sort of a "proof of concept,” and if I like where's it's going, I grab my sketchpad and pencil and proceed from there. I think I'm one of the lucky few who has a solid idea from the get-go, so I don't usually make many changes from when I start to when I finish.

CC: Thanks for your time, Daryl—I know your art for the collection is going to be great!

---

I’ll post updates on Herding Ravens as events warrant. In the meantime, please check out Daryl’s Facebook page for many more examples of his fantastic (in both senses of the word) art.

http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100002237918033#!/profile.php?id=100002237918033&sk=info

#

November 12, 2011

All Our Sons: Joe Paterno, Joe Keller

I was pondering this question last weekend at a performance of Arthur Miller’s cerebral drama After the Fall at Theater J in Washington, DC. It’s a fine production, skillfully directed, well acted, and featuring a truly beautiful set design. But you may be forgiven if you’ve never even heard of After the Fall—it’s not one of Miller’s better-known works, certainly nowhere near the Olympian fame of Death of a Salesman, say, or The Crucible. Written in 1963 (the premiere came a year later), After the Fall is a semi-autobiographical work which takes place in the mind of its protagonist, Quentin, a New York Jewish intellectual examining his life and relationships. Though Quentin is a lawyer rather than a writer, it’s impossible to miss the connections to Miller’s own life, especially when Quentin remembers the break with a friend who named names before the House Un-American Activities Committee, just as Miller’s great pal Elia Kazan did; and, most especially, in the scenes detailing Quentin’s relationship with his unstable, suicidal second wife, Maggie, an internationally famous singer addicted to drugs and alcohol.

Need I remind the patient reader that Arthur Miller’s second wife was Marilyn Monroe?

[image error]

After the Fall isn’t a great play, in large part because it’s simply too personal: for all of Miller’s later denials, it’s impossible to watch it without thinking that everything Quentin says is what Miller really thought, and that the relationships are more or less as they were with their real-life analogues. It’s unfair, of course, and many a writer living a less celebrated life than Mr. Miller’s has no doubt gotten away with the same kind of mildly-disguised autobiography without anyone being the wiser. But when the play premiered in New York only a year and a half after Monroe’s suicide, critics savaged it as crass and tasteless exploitation.

That charge isn’t fair—the play is in many ways brilliantly written—but it’s unlikely that After the Fall will ever be truly embraced by audiences, at least until Miller’s life, and Monroe’s, are completely forgotten. And it’s going to be a long time before that happens.

Still, I’ve found myself thinking a lot about Miller and his career in the week since I saw the play. But not because of the production itself.

I’m thinking of Arthur Miller because of Joe Paterno.

I’ll confess right here and now that until the Penn State football scandal broke, I had never even heard of Joe Paterno. I’d barely even heard of Penn State, and hadn’t the slightest idea they had a world-class football team. Really, I don’t do football. My ignorance of the sport is almost total—though, like anyone who has grown up male in America, I do know the basic rules of the sport thanks to any number of pickup games at recess when I was in middle school. So, yes, I know what “second and six” means. I know how many points a touchdown gets you. I know what a “point after” is. But beyond that very basic level, the world of football is dark to me—as are a lot of other worlds, alas. (Can someone please tell me who the hell “Kim Kardashian” is?)

But there’s something primal about the Penn State scandal, and Coach Paterno’s role in it—something that’s very much akin to the world of Arthur Miller’s work, which was always filled with moral and ethical dilemmas his characters had to face. To be specific, Paterno’s downfall very closely mirrors that of one of Miller’s finest creations, Joe Keller, the protagonist of one of Miller’s greatest plays, All My Sons.

All My Sons was the drama that, in 1947, made its young author famous. It focuses on a day and night in the life of the Keller family, seemingly ordinary middle-class Americans whose paterfamilias, Joe, harbors a terrible secret. As the play proceeds, hints at the nature of the secret begin to be revealed as Joe, the owner of a successful machine-parts factory, is involved in emotional exchanges with his wife, Kate, and particularly his son Chris, a war hero who has come back to America disillusioned and sick at the sight of an America in which “there was no meaning” to the war. “Nobody was changed at all,” Chris bemoans. To the average American, he says, the entire conflict “was a kind of a—bus accident.” Eventually it becomes clear that Joe’s crime was to knowingly sell defective airplane parts to the Army during the war—parts which failed, leading to the deaths of twenty-one men.

Why did he do it?

Because he panicked. In the midst of frantic wartime production, he had to make a fast decision about what to do with the bad parts—and he made the wrong decision, the exact kind of defining moral moment so common in Miller’s writing. From Keller’s perspective, he had built his business for his sons, and he had to do anything he could to save it. Those other boys, those twenty-one American pilots who went down in flames? They weren’t family. It wasn’t pretty, maybe, but he had a choice to make and he made it—“for you,” he tells Chris. “A business for you.”

Confronted by his horrified son, Joe tries to justify his actions: “I’m in business, a man is in business; a hundred and twenty-one cracked, you’re out of business; you got a process, the process don’t work, you’re out of business…they close you up, they tear up your contracts, what the hell’s it to them? You lay forty years into a business and they knock you out in five minutes!”

Do you see what I’m getting at here?

Joe Paterno, it seems, put forty-six years into his “business”—a beloved figure, “a big man,” just as Joe Keller was. Yet at some point in 2002 Joe Paterno was faced with a moral choice—and he made the wrong choice.

True, Paterno’s choice was not as catastrophic as Keller’s. No one died as a result of it. And it’s certainly important to remember that Paterno himself did not abuse a single child. But when faced with the information that a coach was abusing young boys—information presented to him in the form of eyewitness testimony of a ten-year-old being raped in a locker-room shower—Joe Paterno thought it was adequate to mention it to his superior and then drop the matter completely and forever. He did what he was legally required to do, and absolutely nothing else.

So was Paterno as bad as Joe Keller? No. But then there’s something appalling about trying to quantify moral demerits in these situations. And after all, if Paterno followed the letter of the law, then what’s the problem?

Again, Miller’s play addresses this question directly, when Joe talks to his son Chris near the end, pointing out that plenty of others were doing just what he did (just as plenty of others apparently knew about Jerry Sandusky, the abusive coach on the Penn State staff).

Given that lots of others were doing it, “Why,” Joe asks Chris plaintively, “am I bad?”

To which Chris offers this devastating rejoinder: “I know you’re no worse than most, but I thought of you as better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Countless people—players, coaches, fans—saw Joe Paterno as their father. If not literally, then certainly as an example of a beloved father figure. Joe Pa. A great man. Countless people saw Joe Keller the same way.

One article on the Paterno scandal quotes the coach as saying, “Success without honor is an unseasoned dish; it will satisfy your hunger, but it won’t taste good.”

I wonder what Joe Paterno’s success tastes like now.

At the end of All My Sons, Keller finally drops his defenses and admits defeat, realizing his disastrous error—that his flesh-and-blood children were not his only responsibility, his only “sons.”

“They were all my sons,” he acknowledges

.

I wonder if Joe Paterno understands, even now, that all those abused boys were his sons, too.

What makes a great work of literature great? One element is what might be called continuing relevance. When we recognize a human tragedy from literature played out in life, even decades or centuries after the fictional work was created, then we may be in the presence of a great work. All My Sons is a great work

.

Joe Paterno might want to read it.

#

October 20, 2011

A New Interview About the New Novel

Interview by Chris Morey. Reprinted from the Dark Regions Newsletter, October 13, 2011.

How would you describe your new novel “Lullaby for the Rain Girl”?

That’s a tougher question than you might imagine! Again and again in my writing life reviewers have called my work “unclassifiable,” and I guess it is, at least in terms of narrow genre definitions. Mort Castle calls “Lullaby for the Rain Girl” both a “contemporary metaphysical mystery” and a “modern fantasy,” but then rejects both definitions as too limiting. I would say that it’s a story of a man’s relationships with three women, one of whom is alive, one of whom is dead, and one of whom is…well, I’ll leave that for the reader to find out. The novel has a supernatural component—a first for me—but at its core it’s an emotional story about an aging man’s attempts to come to terms with his life and the people in his life, past and present.

How did the novel come about? What spawned the ideas?

Again, that’s not easy to answer. “Rain Girl” is by far my longest and most ambitious novel—at over 120,000 words it’s as long as my first two novels combined—and takes place in two different eras, the early 1980s and the end of the ’90s. What I’d been considering for a long time is what I think of as one of the great literary themes—the way the past imposes itself on the present. You see it everywhere, from “Oedipus Rex” by Sophocles right up to Peter Straub’s wonderful novel “A Dark Matter.” No matter how hard we try to avoid them, the birds—our birds, the birds of our past—invariably come home to roost. My book is very much about that, about how a man’s actions two decades before play out and resonate in unexpected ways later.

I was also thinking about ghost stories, the nature of ghosts, the way that, to me, most ghost stories tend to be in some way unsatisfactory. Usually I just don’t buy that the reason the ghost is haunting the characters in the story is really all that important, you know? I mean, you’re a ghost, you have an entire spirit-world to explore…infinity is laid out at your ghostly feet…and the best you can think of to do is to hang around your old house jumping out at people? What kind of an afterlife is that? Why would ghosts even care about the living at all? So I wanted to write a story in which the haunting would be fully justified, completely believable. But in doing so I discovered that the conventional type of ghost simply didn’t work. I had to create an entirely new kind of creature and, really, an entirely different kind of ghost story. “Lullaby for the Rain Girl” is the result.

If you could describe your writing style in three words, what words would they be?

Let’s see, the words I notice reviewers using most often are “elegant” and “literary,” which are probably pretty good. “Emotional,” too. I don’t write pulp fiction. I don’t write commercial fiction. I don’t write for “markets.” I write what’s inside me, and it often comes from very deep, uncomfortable places. After the piece is finished I have a look around to see if someone might like to publish whatever it is I’ve come up with. Mine is a completely different approach from what a lot of writers in this field do. That’s not a value judgment, just a different attitude.

What authors have inspired you most throughout your life?

Oh man, how much time do you have? Let’s start with Poe, my first favorite writer, whose stories and poems absolutely changed my life when I first discovered them around age eleven. Move to Rod Serling and the Southern California Group in general, particularly the “Twilight Zone” writers—Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, George Clayton Johnson. The early Bradbury. And then, a little later, a variety of literary writers who work the darker side of the street—Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, William Styron, Carson McCullers. And, though he wasn’t exactly an “author,” I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Alfred Hitchcock. No storyteller has meant more to me throughout my life than Hitchcock.

To those unsure about ordering “Lullaby for the Rain Girl,” what would you tell them?

I’d say that if graphic horror and gore are your bag, I am not your writer. My stories are always emotional at their core—human stories about human beings with very human flaws and foibles. They’re about style, mood, atmosphere. The horror writers I love are not part of the blood ’n’ guts crowd. To me there is more worthwhile reading in a single page of Poe or Stoker or Mary Shelley or Lovecraft than in reams of pages by any number of so-called “splatter” writers. If horror doesn’t have a core of humanity, then to me it’s worthless--any kind of writing without that human core is worthless, really. But if human stories are your bag, emotional stories, then you might like “Lullaby for the Rain Girl.” I hope a few adventurous readers will give it a try.

For information on how to pre-order "Lullaby for the Rain Girl," please visit http://www.darkregions.com/lullaby-for-the-rain-girl-by-christopher-conlon/.

#

October 11, 2011

My New Novel, Up For Preorder

http://www.darkregions.com/lullaby-for-the-rain-girl-by-christopher-conlon/

Why preorder, you ask? Why not just wait for the book to come out? Well, this is a very limited hardcover edition, and while there will be an e-book some months after the hardcover release, there’s no guarantee of any future paperback version. So if you want a physical copy (and Dark Regions does beautiful books, real collector’s items), this is your best—and possibly only—chance of getting one. Lullaby for the Rain Girl is my most ambitious novel yet, and at 120,000+ words it’s approximately the length of my first two novels combined. So this is a big one!

While you’re considering that, I’d also like to point out that a nice little profile of me, focusing on my life in poetry, just went up on the D.C. Examiner website. It’s here:

http://www.examiner.com/poetry-in-washington-dc/profile-of-a-dc-poet-christopher-conlon

Finally, in the category of “exclusives,” I do want to let you know that there should be two more Conlon books coming in 2012, in addition to Rain Girl. One is a collection of flash fiction; the other, a “new and selected poems.” I'll pass on information about these just as soon as everything’s official….

#