The Books of 2011: Best of a Bad Year

Is it possible that I’m getting old?

Well, for another seven months or so I’ll remain on the right side of 50, but still, thinking about writing a blog on my favorite books of 2011 has made me suspect a creeping curmudgeonliness lurking within the black and bitter recesses of my heart.

Truth is, I didn’t like very much of what I read in 2011. Naturally I encountered lots of good books this year, and re-read several old favorites; but I’m talking here about new books—ones with 2011 copyright dates. For some reason it seemed an unusually weak year to me.

Now I’m not a professional book reviewer, and I never make any effort in any year to read a representative sampling of anything. For all I know, 2011 may be looked at by future generations as the greatest year in publishing history. But in terms of what I read…not so much. I did find a few outstanding titles—books I really liked—and one I loved so much it became the immediate, obvious choice for Conlon’s Favorite Book of the Year. But I felt let down by many new books, including ones by long-time favorite writers of mine.

Here are a few that come to mind.

Now in his 80s, Donald Hall brought out what was announced as his final poetry collection, The Back Chamber; while there are certainly meritorious individual poems therein, I found this slim volume to be surprisingly feeble, mostly covering familiar topics (Jane Kenyon, Eagle Pond) in ways far less memorable than what we find in his earlier work. Readers should seek out Hall’s searing verse-memoir Without, along with his greatest-hits collection White Apples and the Taste of Stone, for the best examples of this great American poet’s work.

Joyce Carol Oates, possibly the finest fiction writer this country currently has, published a collection called Give Me Your Heart: Tales of Mystery and Suspense in 2011. Oates is always worth reading, but I recall thinking that this was a lesser book from her, and looking over the Table of Contents now I see that I can actually remember only one of these stories, the erotically charged and thoroughly disturbing “Strip Poker.” Yet there are ten stories in the book. I read them all. Where did the other nine go?

In recent years I’ve become a fan of Cherie Priest’s “Clockwork Century” books, a Steampunk series that commenced with Boneshaker and continued with Dreadnought and the novella Clementine. I greatly enjoyed all of these inventive, zombie-laced bits of fanciful Victoriana—so why did Priest’s latest, Ganymede, fall so completely flat for me? It’s possible it’s not the author’s fault; in truth, I rarely read series books, and when I do, I usually check out after the second or third volume (this happened with Alexander McCall Smith’s “No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency” books, for instance). Maybe I’ve just gone to the Clockwork Century well one too many times at this point. Whatever the reasons, I must classify Ganymede as a disappointment.

Another old favorite, the great Richard Matheson, published his first novel in a long while this year, Other Kingdoms, and while it marked a considerable improvement over his previous couple of efforts, it’s undeniably a slight story—a readable little fantasy tale, nothing more. I can’t recommend it with any particular enthusiasm.

I didn’t care much for a memoir about one of my old favorites, either. Alexandra Styron’s Reading My Father focuses, of course, on her dad William Styron, author of Sophie’s Choice, Darkness Visible, and The Confessions of Nat Turner. Styron (the elder) was a formative writer for me, the quality of his prose a revelation in that period, the early ’80s, when I was transitioning from reading genre fiction to more literary work—Sophie’s Choice, in particular, was an unforgettable, transformative experience. I’m not sure how well Mr. Styron’s works will age—are aging, even now—but at least in memory, he remains a central writer of my life. His daughter, herself the author of one mildly well-received novel, seems to promise in her early pages some shocking revelations about The Great Man, but all we really get are her impressions that he could be self-absorbed (big surprise), insensitive (even bigger), and boorish (biggest of all). I was left with the thought that this memoir had no real point other than to get its author another book contract. (Memo to Alexandra Styron: My dad was way worse than yours.)

Of course I made efforts to branch out this year, as I always do, to try writers I’d never read—ones who either received rapturous reviews that caught my eye or else were recommended by friends. These writers included Madison Smartt Bell, Rachel Simon, and John R. Little, but The Color of Night, The Story of Beautiful Girl, and Ursa Major all left me disappointed. None seemed fully realized visions of what the books appeared to be trying to do, and none left me wishing to read more by their respective authors.

I read a number of new anthologies this year, mostly in genre fiction. Of these, the best was probably Jonathan Strahan’s Engineering Infinity, a gathering of (mostly) “hard” science fiction stories which features outstanding new work by Stephen Baxter, Charles Stross and others, yet which—like virtually all original anthologies—seemed to me very uneven, with too many stories that didn’t really fit into the editor’s self-described concept of the book at all.

Well, then, what did Conlon like this year?

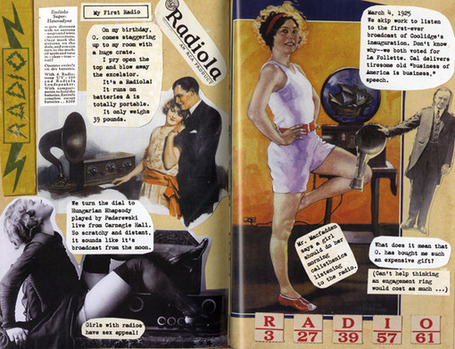

Caroline Preston’s The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt: A Novel in Pictures was pleasing. This volume follows the life of the eponymous Frankie in the 1920s, from her childhood in New Hampshire through Vassar College, Greenwich Village, and Paris. But The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt takes the form of exactly that, Frankie’s scrapbook—hundreds of vintage photos, news items, advertisements and so on, all with Frankie’s ongoing narration typed out and pasted in. The story itself isn’t much more than a straightforward period romance, and the book’s promotional materials oversell the volume as the “first-ever scrapbook novel” (it’s really just a variation on the standard graphic novel), but it’s a lot of fun—certainly a must-read for anyone interested in the 1920s. (And while you’re at it, if you’d really like to immerse yourself in the ’20s, when you go to pick up The Scrapbook of Frankie Pratt at your local…er, not Borders, but maybe B & N, or an independent bookseller, why not stop by your local movie house to check out either Hugo—a pretty good movie, based on a fanciful reimagining of the life of early filmmaker George Méliès—or, even better, the transcendently wonderful The Artist, a silent-film romance of sorts set in 1920s Hollywood, and far and away Conlon’s choice for Favorite Movie of the Year?)

Anyway, moving right along: Horoscopes for the Dead by Billy Collins was my favorite book of poems this year. Collins has often been called the most popular American poet since Robert Frost, and this book reminds us why. No one I can think of in American verse today has the easy, urbane charm of Collins; no poet feels like better company. Horoscopes for the Dead is a somewhat darker book than the ones that have come before, with more concern toward aging and death, but it’s a fine volume that any poetry reader should enjoy.

Norman Prentiss, author of one of my favorites from last year—the novella Invisible Fences—returned in 2011 with Four Legs in the Morning, a suite of three stories about the mysterious and powerful Dr. Sibley, Chair of the English and Classical Literature Department at Graysonville University. These are fantasy/horror tales of a high order, filled with inventiveness and wit. I can’t say I’m a huge fan of the odd-sized edition I received (it measures roughly 5 x 9, and is just as awkward to hold in your hands as those dimensions imply—frankly, it made me long for an ebook version), but the volume is enhanced by excellent illustrations by Steven Gilberts.

I also enjoyed All the Lives He Led, the latest science fiction novel by Frederik Pohl, one of the grandmasters of the field. Now in his 90s, Pohl weaves an exciting tale here, surely his best novel in at least twenty years. In 2079 much of the United States is reeling from the dual effects of terrorism and the after-effects of a massive eruption at Yellowstone which has covered most of the western U.S. in volcanic ash and led to acid rain and crop failures worldwide. Our main character, Brad Sheridan, lives a life of petty crime on Staten Island until he escapes to Egypt and then Italy, getting a job at, of all things, a theme park at Pompeii—where he eventually becomes aware of a huge terrorist plot, one conceived on an unprecedented scale. I loved Pohl’s typically ironic tone in this book, and other than its somewhat rushed conclusion, All The Lives He Led seemed to me to fire on all cylinders.

Possibly my favorite novel of 2011 was no real surprise—since falling in love with the work of the great Portuguese fantasist José Saramago a few years ago, I’ve read little by him I didn’t think was first-rate (and I’ve read nearly everything by him available in English). Cain, advertised as his final novel—Saramago died in 2010—is a wild, ribald, and thoroughly profane retelling of portions of the Bible from the point of view of the eternal wanderer himself, Cain, who encounters Noah, Job, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and other Biblical highlights, all the while arguing with God about what all of it is supposed to mean. Though Christians who lack a funny bone may have trouble with this book, I found it utterly delightful from first page to last.

As it turned out, though, my Favorite Book of 2011 was neither fiction nor poetry. (By the way, for those of you keeping score at home, my previous Favorite Book of the Year choices were Wild Nights! by Joyce Carol Oates [2008], Endpoint and Other Poems by John Updike [2009], and The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse edited by Caroline Franklin [2010].)

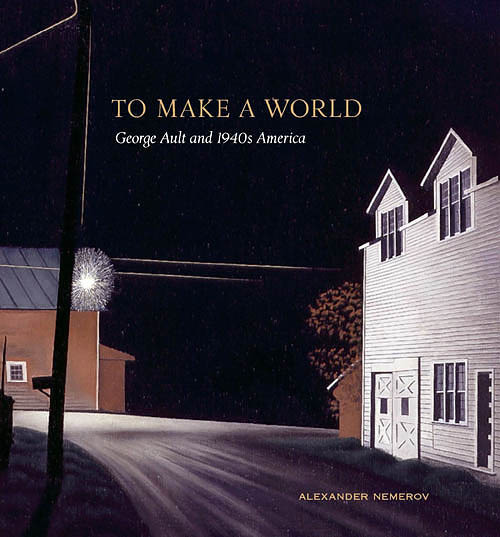

Instead, my Favorite Book of 2011 was the companion volume for my favorite exhibition of 2011, which I saw three times at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum in D.C.—To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America, by Alexander Nemerov.

Truth is, I had never even heard of George Ault before I saw a review of this exhibition in the Washington Post. This surprised me, since I tend to like American art of the mid-twentieth century (think Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth), just as I’m also fond of mid-century American music (Copland, Bernstein, Roy Harris), theater (Williams, Miller), fiction (Capote, Vidal, McCullers), poetry (Weldon Kees, Winfield Townley Scott), radio drama (Corwin, Oboler)—and, of course, movies. To Make a World—both the exhibition and the book—makes a world of a case for Ault, a relatively little-known realist painter who was born in Cleveland in 1891 but spent much of his life in New Jersey and, finally, Woodstock, New York, where he created many of his best paintings and died, apparently a suicide, in 1948. In some ways Ault’s paintings are reminiscent of Hopper’s—that same sense of isolation and alienation among the soulless structures of modern America—but Ault is more rural in orientation (and, it must be admitted, less adept at depicting the human form). His five paintings of the crossroads at Russell’s Corners in Woodstock—one is reproduced on the cover of the book—are surely his masterpieces, each with a brooding silence fully the equal of Hopper’s. To see them displayed together at the American Art Museum was a profound experience; to study them gathered in this book is only slightly less so.

But To Make a World, exhibition and book, focuses not just on Ault, but on numerous lesser-known American artists of the period as well, and I found myself moved by the canvases of Rockwell Kent, Raphael Gleitsmann (below), Kelly Fearing, and Charles Sheeler, among others. The reproductions of some of these are, alas, a bit darker than they should be, but the book still manages to effectively document and discuss the works of these numerous masterful yet half-forgotten artists. The cogently-written text by Alexander Nemerov makes all sorts of unexpected, illuminating connections.

To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America is a volume I’ve already returned to many times, and will again. It’s my Favorite Book of 2011.

Here’s to good reading in 2012....

#