Christopher Conlon's Blog, page 5

November 23, 2012

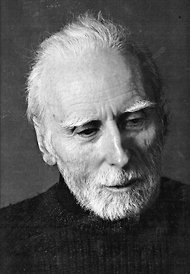

Jack Gilbert 1925-2012

Jack Gilbert died a couple of weeks ago—on November 13, to be precise, at age 87. His was a long and productive life, one devoted almost entirely to poetry; yet, as several writers have put it, he and his career existed practically “off the grid.” Eschewing the usual paths to power and fame in verse (no running an MFA program for him) and publishing very little—only five full-length collections of new work in fifty years—Gilbert nonetheless maintained a kind of cult following. Since I first discovered his work in the mid-1980s (through a copy of his collection Monolithos at Northtown Books in Arcata, California), he’s been one of the basic poets of my life. If you’re unfamiliar with this great contemporary master, I can only urge you to pick up one of his books—The Great Fires is my own favorite.

Here are the first lines of one of his better-known poems, “A Brief for the Defense.”

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

Otherwise the mornings before summer dawn would not

be made so fine. The Bengal tiger would not

be fashioned so miraculously well. The poor women

at the fountain are laughing together between

the suffering they have known and the awfulness

in their future, smiling and laughing while somebody

in the village is very sick. There is laughter

every day in the terrible streets of Calcutta,

and the women laugh in the cages of Bombay.

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

(Complete poem here: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/a-brief-for-the-defense/)

Originally from Pittsburgh, Gilbert was a restless traveler his entire life. In a (very positive) review of Gilbert’s Collected Poems in the New York Times, David Orr wrote that Gilbert “sounds like a man who’s spent a lot of time on a Greek island doing nothing but cleaning squid, having affairs and thinking about poetry and purity.” Indeed, that’s exactly what he does sound like, and that’s exactly the life Gilbert led for many years on an island in the Aegean. Later he resided in Massachusetts, but when I picture Jack Gilbert in my mind I invariably see him sweeping the inside of a small hut on that Greek island, sunlight pouring through the dusty windows, some fruit in a bowl on the good plain table in the center of the room.

It’s a Good Life

for Jack Gilbert

copyright © 2012 by Christopher Conlon

Living in the stone hut on the island in the Aegean so many years brought him a closeness to things, to rocks and bushes and brush. When he swept his stone floor he would find pieces of poems in the dust and polish them so that they gleamed like the glittering lights of passing ships at dusk. It got so there was no difference between him and the outward materials of life and there came to be a great profound sensuality between him and the vast world of things. When he wrote of scorpions or stones the writing held an electric eroticism that sparked and crackled like tiny thunderclaps on the bright pages of the sea. When he died the light under his door mourned and the spiders spun silently in remembrance.

#

September 30, 2012

Blogdanovich and the Greatest Film Ever Made

The once-a-decade Sight & Sound critics’ poll of the greatest films ever made is old news by now, the headline having been that longtime Number One Greatest Film Citizen Kane has been displaced after many decades by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (if you haven’t seen the poll: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news/50-greatest-films-all-time).

But I only recently discovered that the famed film director, producer, actor, historian etc. Peter Bogdanovich keeps a blog—called, inevitably, “Blogdanovich”—and that in an August entry he discussed this poll, making some salient points and a few that, to me, are not quite so salient. The full blog entry is here (http://blogs.indiewire.com/peterbogdanovich/the-sight-and-sound-poll).

In brief, Mr. Bogdanovich reveals that he was asked to participate by creating his own top ten list of the greatest films of all time. He tried, he writes, but he “found the exercise impossible to complete.” He arrived at the conclusion that “the whole rating idea is anti-artistic, anti-film culture, just absurdly reductive.”

Of course Mr. Bogdanovich is perfectly correct about this.

He is also perfectly wrong.

Of course any attempt to rank artistic works is doomed from the outset, whether it’s a Greatest Films of All Time list or the winner of the Best Picture Oscar. For that matter, one can say the same thing about the Emmys, the Tonys, and Golden Globes. We can add in the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Edgar Award, the Hugo, the Nebula, the World Fantasy Award, the Golden Spur, the Bram Stoker Award, any critic’s top ten or twenty or hundred list of anything…novels, poems, plays, paintings, sitcoms, porn films, anything at all that exists at any point within the sphere of “artistic endeavor.”

All such lists are rubbish, and they’re all wrong.

Unless, of course, you are the one who made the list.

Naturally these lists are subjective; they can’t be anything else. A large poll like Sight & Sound’s tries to locate some generalized agreement among many assumedly informed individuals, but one could have asked other, similarly informed individuals and no doubt have gotten a much different list of the Greatest Films of All Time.

But I can’t go along with Mr. Bogdanovich’s assessment that such an endeavor is “anti-artistic” and “absurdly reductive.”

The truth is, such lists—and awards like the ones I’ve listed—are nothing but a snapshot in time: how certain individuals responded to a particular question at a particular moment. They mean nothing else. Politics often play into people’s choices, along with personal hostilities and resentments. Orson Welles had alienated much of Hollywood at the time he was making Kane, and he paid for it by having his film win no Oscar except Best Screenplay (which was really a way of acknowledging old Hollywood pro Herman Mankiewicz, its co-author). The Best Picture winner, How Green Was My Valley, is a nice little sentimental picture, but history has surely shown how wrong the judgment of the Academy voters was that year.

You want wrong, though? How about this: though it only won a single statuette, at least Kane received nine nominations, many in major categories including Best Picture, Actor, and Director. But the current “greatest film of all time,” Vertigo, received only two, both in minor categories (Art Direction, Sound)—and lost both.

So the awards are useless, right? Not really. They’re valuable if, for nothing else, generating discussion. After all, what better way is there to get people thinking about Citizen Kane than to tell them that it won no major awards in its year of release? Or that Alfred Hitchcock never won an Academy Award—and was not even nominated for Vertigo?

Anyway, can there even be something like a “greatest film of all time”? What does it mean? “Greatest” in what sense? Most entertaining? (In that case Star Wars or Titanic or Gone With the Wind would likely be most filmgoers’ top choice; Citizen Kane wouldn’t even make the top hundred.) Most historically important? Most technically innovative? There’s no answer.

Except that you have an answer, don’t you?

Of course you do.

For you, the greatest film of all time is the one you enjoyed the most, that had the greatest emotional impact on you, the one you remember most vividly, the one you can watch again and again and never become bored.

You see, that’s where lists like this have value—as discussion generators.

Don’t see your favorite movie on the list? Well, what does that say about the list and the people who voted on it? For that matter, what does it say about you? If you’ve never seen Vertigo, don’t you want to, now that you discover that it’s the “greatest”? Doesn’t that ranking make you at least a little curious? And if your own choice doesn’t appear on the list, don’t you want to coattail your friends and say, “Forget Sight & Sound! You want great? I’ll show you the greatest movie ever made! Sit down with me and watch Showgirls!”

Of course, I say all this as a preening film-school type who can always look at a list like this and feel confident that many of my own favorite movies will be on it. Looking at such a list helps reinforce my ego, my calm assurance that I, naturally, have the finest taste in the world. If your favorite movie is Ernest Goes to Camp or Troll 2, however, this might not be true.

There’s much I could say about many of the films listed in the poll, but I’ll just say this. When I was about eleven, I began to discover the works of Alfred Hitchcock through reruns of his movies on TV (also his TV show and the mystery anthologies that carried his name). By the time I was twelve or so I had seen and fallen in love with Lifeboat, Notorious, Shadow of a Doubt, Frenzy, The Birds, and, of course, Psycho.

At age eighteen I finally saw Citizen Kane thanks to my videotaping a late-night TV screening, and I went completely mad for it. I loved the film so much that on more than one weekend night I would come home from my job as busboy at the Valley Steak House—usually around ten or eleven p.m.—pop open a can of Coke (caffeine seemed to have no effect on me in those days), and plug my home-taped VHS of Kane into my RCA top-loading VCR. I would watch it straight through.

Then I would rewind the tape and watch it straight through again.

By eighteen I knew that the two greatest moviemakers in the history of the world were Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles.

By choosing Vertigo as Number One and Kane as Number Two, the critics of the world have finally caught up with what I knew when I was still a teenager.

Thanks, film critics of the world. I always knew I was right!

#

August 5, 2012

A New Interview

A new interview with me, conducted by indie publisher and writer JW Schnarr, has just gone up, and you can find it right here: http://jwschnarr.blogspot.com/2012/08/an-interview-with-bram-stoker-winner.html

Enjoy!

July 16, 2012

New Collection Up For Pre-Order!

I’m pleased to announce that my forthcoming collection of flash fiction, Herding Ravens: Bon-Bons and Cold Cuts, is now available for pre-order from the estimable horror and dark fantasy publisher Bad Moon Books. The book, featuring evocative interior art by Daryl Earnest and a spectacular cover by John Pierro, features over two dozen of my “bon-bons,” very short stories of the weird and wild. Read all about it on the Bad Moon Books website:

http://www.badmoonbooks.com/product.php?productid=3190&cat=0&page=1

Note that this link takes you to the pre-order page for the signed, limited edition hardcover, which Bad Moon has priced at $30.00. If you’re looking for an edition a bit lighter on the wallet, check out the $18.00 trade paperback edition:

http://www.badmoonbooks.com/product.php?productid=3191

Both editions of Herding Ravens are scheduled for release in August. Pre-ordering now guarantees that you’ll receive your copy—which is especially important with the hardcover, since the final print run is determined by the number of pre-orders Bad Moon receives.

The Town Elders

From Herding Ravens: Bon-Bons and Cold Cuts

Bad Moon Books, 2012

Copyright © Christopher Conlon

In their wisdom the town elders decreed that an ice skating rink would be built, and it was. Hundreds of happy skaters, loving couples, single men and women, teenagers, families with small wobble-walking children, came from miles around bundled in their snow clothes to enjoy gliding about on the ice under blue and white winter skies. Unfortunately the rink had been built, for reasons only the town elders might have been able to explain, over the top of a small lake, and as the weather turned from winter to spring skaters began to notice cracks which were at first no more than tiny pencil-scratches in the ice but which soon expanded to highly dangerous crevices and chasms. Skaters began to disappear under the ice into the lake, at first occasionally, and then on an alarmingly regular basis.

When blossoms began opening all over town and the weather had turned the warm of sandals and shorts, the ice rink was dismantled entirely and the same persons who had enjoyed the winter skating, that is, those who still survived, came to the lake, disrobing almost completely and allowing the sun to bronze their skin for hours on end. They ate from picnic baskets and cooked hamburgers on small barbeques. Many of them swam delightedly in the lake, paddling this way and that and playfully splashing each other. One problem, which the town elders failed entirely to solve, was that at times corpses left over from the fiasco of the skating rink would suddenly surface, and at the most inopportune times. It became an embarrassment and something of a public relations problem, never more so than when a young woman dragged a male corpse to shore, proclaiming it to be what remained of her first and indeed only true love, thereupon carrying the disintegrating thing over her shoulders to the local courthouse where she demanded that the town elders allow her to marry it. She was informed that the law did not allow for the marriage of woman to corpse, and this created a small but similarly embarrassing civil rights kerfuffle. The woman ultimately decided to cohabitate with her dearly beloved, a decision which generated some controversy in itself—but not, the town elders were certain, on the level that would have occurred had they allowed the two of them to enter into the state of holy matrimony.

One odd aspect to this entire problem of the corpses in the lake was that the lake never seemed to tire of disgorging corpses onto the shore. After a time it became embarrassingly apparent that far more deceased persons were washing up onto the sands than had vanished from the ice rink during the winter. The town elders formed a committee to study this apparently impossible problem, but no final report from this committee is known to have been issued, or if issued, it appears to have been lost.

In the meantime winter came again and the lake was once more crusted over with smooth, inviting ice. Again came the young lovers and the men and women and the families with their small wobble-walking children. But now some noticed odd round bumps appearing on the surface of the ice, bumps which slowly split the ice in places through which strange things, at first unrecognizable, began to grow. Some persons believed that the growths might be some new strain of cauliflower or tomato, but soon enough it became apparent that the growths were in fact human beings. One would see the clear ice-encrusted outlines of a forehead, a temple, a set of ears, frost-filled strands of hair. This for the town elders was the ultimate humiliation, and it was quickly decided that something would have to be done. Fortunately there was a course of action readily and even obviously available to them, and they took it. The town elders began to cultivate this unprecedented winter crop.

One would see them late at night in their heavy coats tilling the ice rink with shovels and hoes, always careful to smooth the ice again after pulling nature’s peculiar yield from the ice. Eventually the story, which was true, went around that the crops were in fact delicious to eat when prepared properly, and soon the townspeople themselves were tending what was now less a skating rink than a glorious winter garden. Neighbors laughed and joked about this unexpected bounty and exchanged recipes enthusiastically.

If you ever decide to go to the town, by all means do so in the depths of winter. Buy one of the readily-available cookbooks for sale at various shops near the garden, and then go and collect some winter crops for your own dinner. There’s more than enough for everyone. Indeed, the supply is ample and even, at times, overwhelming. The heads of teenaged girls are said to be especially succulent when stewed for several hours with carrot and onion in chicken stock. Or snap off a handful of baby fingers, which are simple to gather and requite no preparation at all. The town elders assure us that they are delicious straight from the ice, sweet and with an unexpected tanginess.

[image error]

#

June 26, 2012

Behind a Dark Star: Remembering Sal Mineo

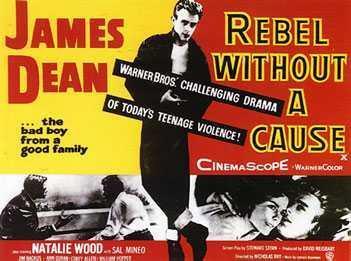

Perhaps no Hollywood legend is stranger than the fate of the three stars of that doom-haunted teenage classic, 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause.

You remember the film, of course. James Dean, in his image-defining role, plays alienated adolescent Jim Stark, whose family has just moved to a new town because of some “trouble” the boy had gotten into before, when he “messed a kid up” in some undisclosed but presumably violent manner. But his new life starts out extraordinarily badly: when we first see him he’s drunk and passing out in an alley, upon which time the cops pick him up and take him in; at the police station he first sees Judy (Natalie Wood), a bad girl type picked up for “wandering around at one o’clock in the morning,” and Plato (Sal Mineo), a deeply troubled younger boy who has, we learn, shot a litter of puppies for no apparent reason. The teen angst only builds from there, as the next morning Jim quickly runs afoul of his new school’s dominant gang and finds himself in a variety of dangerous situations, including a knife fight and “chickee run” with the gang’s leader, Buzz. Eventually Jim, Judy, and Plato all repair to a conveniently-located derelict mansion and play at fantasies of being a proper family—husband, wife, son—until fate, in the form of the gang and then the police, closes in.

Rebel Without a Cause, for all its melodramatic corn, is an unforgettable film, and one that can still speak to young people today. In it, James Dean defined the teen rebel for all time: angst-ridden, alienated, yet strangely beautiful—and so damn cool in his red windbreaker, white T-shirt, and pegged blue jeans!

Dean is so iconic in Rebel that it makes me wonder: Am I the only person on earth to think that the real star of this film is not the intense but scenery-chewing Mr. Dean, nor even the histrionic Natalie Wood, but rather Sal Mineo, whose turn as Plato hits exactly the right note of loneliness, neediness, desperation, even incipient psychosis—a performance so real that even today it’s sometimes painful to watch?

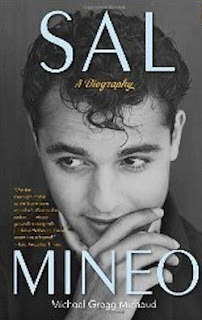

Born into a poor Italian immigrant family in the Bronx in 1939, Mineo was sixteen when he shot Rebel Without a Cause (so unlike most of moviedom’s “teenagers”—Dean, for instance, was twenty-four). Alas, Rebel—only his third movie—came to define his spotty career. As Michael Gregg Michaud illustrates in his fine book, simply titled Sal Mineo: A Biography, the young star did enjoy a brief period as a teen idol for a few years after Rebel, making numerous B-movies and a few big ones (he has a small part in Dean’s last picture, Giant); thousands of girls belonged to the official Sal Mineo Fan Club, and he even became a singing star, recording several modest hits—the biggest, a rather awful number called “Start Movin’ (In My Direction),” made it to #9 on the Billboard chart in 1957. (You can hear it on YouTube if you’re feeling masochistic—Mineo knew he was no singer, but his studio insisted.) Some of what was dubbed “Mineo Mania” by the fan magazines of the time may have been displaced passion for the late James Dean, but much of it was real, too. Mineo had an undeniably unique quality on film—an angelic little-boy face somehow infused with a knowing sensuality, mixed with a screen personality that exuded danger and vulnerability at the same time.

[image error]

Things went pretty well for Mineo for a few years after Rebel. One of his standout roles came in The Gene Krupa Story (1959), in which his dedication as an actor is obvious—he not only learned to play the drums in order to portray the great jazz drummer, but he learned Krupa’s spectacular solos beat for beat. It’s amazing to watch Mineo in the musical sequences—by their nature drums are an instrument that can’t be easily faked, and what we hear on the soundtrack is actually Krupa, but Mineo matches the playing almost perfectly—playing which includes some of the most sensational jazz solos ever recorded. There is no cheap cutting-away, no use of low angles to keep us from seeing what’s really happening, no sudden close-ups of what are obviously somebody else’s hands holding those flying sticks—Mineo is doing it. The movie itself is only a typical bio-pic of its time, but the musical scenes represent an astonishing feat of seriousness in an actor’s preparation and performance.

In 1960 Mineo appeared in Exodus, and earned his second Academy Award nomination (the first was for Rebel). After that, professionally speaking, it was a long downward slide. By the late ’60s he was doing game shows and small guest-starring roles on minor TV dramas; he even appeared as a talking orangutan in a brief role in Escape from the Planet of the Apes.

His personal life also underwent profound changes in this period. In his glory days Mineo was a confirmed womanizer, and enjoyed a long and intense relationship with actress Jill Haworth, his co-star in Exodus. By 1963, however, different feelings had begun to emerge in him, and an affair with future teen heartthrob Bobby Sherman began for Mineo what became a virtually complete switchover sexually to the company of men. This is an intriguing aspect of the actor’s life I wish Michaud had delved into further—I found myself wondering what was happening emotionally to this ill-educated poor boy from the Bronx as his feelings edged away from what was culturally acceptable toward what was strictly forbidden, even unmentionable. In any event, he quickly became, if anything, even more sexually busy with men than he had been with women. (This put me in mind of a line from Tennessee Williams’ Memoirs: “When I came out, it was with a hell of a bang.”)

But his career continued its decline. Unlike the professional troubles of so many Hollywood stars, though, Mineo’s did not stem from drink or drugs; they appear to have been the result of nothing more complicated than the fact he was difficult to cast, being much too small and boyish for most leading-man roles. His physical appearance doomed him to play, mostly, not the hero, but the hero’s best friend; not the villain, but the villain’s crazy sidekick.

But his career continued its decline. Unlike the professional troubles of so many Hollywood stars, though, Mineo’s did not stem from drink or drugs; they appear to have been the result of nothing more complicated than the fact he was difficult to cast, being much too small and boyish for most leading-man roles. His physical appearance doomed him to play, mostly, not the hero, but the hero’s best friend; not the villain, but the villain’s crazy sidekick.

Yet Michaud’s biography makes Sal Mineo an appealing guy, an intensely creative soul bursting with movie and theatre ideas (he got his start as a child actor in the original Broadway production of The King and I and directed plays late in life), an artist who never stopped trying, always moving forward into the next project with enthusiasm and hope.

But today Sal Mineo is remembered for only two things: Rebel Without a Cause—and the fact that he was stabbed to death in a parking lot off Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard in 1976.

Thus Mineo turned out to be Part 2 of the Rebel “curse” in which each star suffered an unnatural premature death: first was Dean in a car crash in 1955, last was Wood drunk off a boat in 1981. Given how dark and nihilistic all three of the teen protagonists are in Rebel, these coincidences of fate are at least slightly bizarre, and can hardly help but add a level of sadness and grotesquerie to any viewing of the film now.

Mineo was 37 when he was killed. The semi-forgotten star died tens of thousands of dollars in debt.

Nor did Mineo’s killing, a completely random act by a violent petty thief named Lionel Williams—who didn’t even know he’d murdered somebody famous until he saw coverage of the case on TV later—have any cultural or symbolic resonance that might have enhanced the actor’s posthumous reputation. (This can certainly happen—witness the postmortem legends of Marilyn Monroe, John Lennon, Tupac Shakur, or indeed James Dean, all of whom died in ways that seemed either gruesomely appropriate or bitterly ironic, and whose manners of death only increased their fame.) Ultimately Mineo seemed just another Hollywood has-been who came to a bad end. In that he shares a great deal with another half-forgotten star who died in a randomly bizarre way—Oscar winner Gig Young, who for unknown reasons murdered his wife and then committed suicide in 1978 (and who is also the subject of a very good biography, Final Gig by George Eels). In both cases the deaths seemed random, meaningless, disturbing. But not disturbing in ways that led to discussions of larger societal issues such as, say, the objectification of women (Monroe), the legacy of the sixties (Lennon), urban violence (Shakur), or wild untamed youth (Dean). In Mineo’s case, as in Young’s, there seems almost nothing to say.

And that’s too bad, because Sal Mineo was a fine actor who deserved better—a better life, a better career, and most certainly a better death. But so it was. And if, in terms of his acting, he is remembered for nothing besides Plato, the most poignant of the three unhappy teenagers in the classic Rebel Without a Cause, it’s worth noting that such a small but real legacy is more than most actors leave behind.

Perhaps it’s enough.

#

April 4, 2012

Update on My Forthcoming Book

Work on what should be my next book, a collection of flash fiction from Bad Moon titled Herding Ravens: Bon-Bons and Cold Cuts, proceeds apace. The terrific Daryl Earnest is more than halfway done with the drawings now, and the volume should be released this summer. Here’s a story from the book, complete with Daryl’s art.

Political Poem

copyright © Christopher Conlon

She stepped into the shower and as the water sprayed her skin she began rubbing her arms with two coarse rags. She rubbed and rubbed until her arms were exhausted, long after the skin had been pulled apart like webbing and blood had run down her belly and legs. After many days of this rubbing she at last reached the final layer, past muscle and gristle and bone: and she found that she was, in the end, colorless; or, if not colorless, then a wispy indistinguishable color, like the stark edge of a desert horizon. Having succeeded as far as this, she rubbed the rest of her body clean of color as well: face, breasts, thighs, feet: and when she stepped out of the shower at last and looked into the mirror she saw only a hint of shape or form, like puffs of sculptured steam. Her dress fell through her body so she went naked into the street and found that no one else saw her and when they bumped into her it was as if they hadn’t touched anything solid but rather a mysterious hesitation in the air they walked in.

After many days and nights naked on the streets, hungry, shivering in the cold, she at last saw a few others like her huddling in doorways and under park benches. They looked like creatures made of water and she learned from watching them that they could not eat food, swallowing instead only tasteless unsatisfying shadows. Day after day she grew weaker and eventually she tried to speak to another of the water people but found that he—it was a man, she thought, but then again perhaps not—was strengthless, hollow, mute. Finally she knelt in the doorway where she had been living and waited, feeling doors flying wide inside her head. She crumpled then, tumbling weightlessly down the dark streets, shredding apart as she rolled.

[image error]art copyright Daryl Earnest#

March 13, 2012

Lullaby for the Rain Girl - New Novel Now Available

I’m happy to be able to announce that, after several delays, the signed and numbered hardcover edition of my new novel, Lullaby for the Rain Girl, is now available from Dark Regions Press. Complete information is here: http://www.darkregions.com/lullaby-for-the-rain-girl-by-christopher-conlon/

So what’s it about? Lullaby for the Rain Girl focuses on high school teacher Ben Fall’s relationships with the three women in his life—one of whom is alive, one of whom is dead, and one of whom is…well, something else. It’s my largest novel yet—at 120,000 words it’s nearly the length of Midnight on Mourn Street and A Matrix of Angels combined—and it’s my first one with a supernatural theme.

The well-trafficked website Horror Librarian calls Lullaby for the Rain Girl “an unsettling story that mesmerizes the reader as the threads of past and present are drawn together, with loose ends that suggest various possible realities…those seeking an unsettling, emotionally involving, and often mysterious story will have a treat in store. Recommended.”

Here’s a peek at the opening pages of Lullaby for the Rain Girl.

*

The buckets and pans are still catching the rain that drips and trickles around us, but if the storm keeps up like this much longer I don’t know.

The power has been out for hours. Yet I know this building has backup generators. By candlelight I telephone downstairs to the lobby again and again. No answer. Thunder, fierce and sudden, roils around us, shaking the walls and rattling the pictures in their frames.

Finally I get up and move to the window, look the eight floors below at a street dotted sparsely with headlights that float like spirits in the rainbroken dark.

Such a long, long drop. So lonely a fall...

“Ben?”

I go to her, touch her hair. Seated, she pushes her face into the belly of my shirt. Lightning flashes: the room glows blue-white.

“I’m scared, Ben.”

“Don’t be. The building won’t collapse.”

“It feels like it will.”

“It’s all right.” I tousle her hair and step away again.

“Don’t leave me. Please.”

“I’m right here.”

“I can hardly see you.”

I sit next to her again with a sigh and touch her hand on the tabletop. She grabs my fingers and clings to them.

“Ben, there are so many things I don’t understand.”

“Do you think that I do?”

“Yes,” she says. “No. I don’t know.”

“I don’t understand anything. Not a thing.”

“Do you think the morning will ever come?”

“Yes.”

“Will it be sunny? And nice?”

“Maybe. It’ll be morning, anyway.”

“Please don’t let go of my hand.”

“I won’t.”

We listen to the rain spray the window, drip into the buckets.

“I wish we could go somewhere else,” she says.

“Where?”

“Anywhere. Anywhere but here.”

“We can’t.”

“I know. But—we can’t be here forever. We’ll get out somehow. Won’t we?”

“If we don’t, someone is bound to come get us. After the storm has passed.”

Lightning sparks the sky once more. In that instant my eyes happen to be on the window and—ah—I see the girl suspended there, hovering outside, staring into the apartment. Her dark eyes are enormous, glistening. Hungry.

But before the lightning has gone black, before I can stand or cry out, she’s vanished again.

Impossible, of course. She wasn’t there. She couldn’t have been there.

“We’re okay here,” I say at last, trying to convince myself. “We’re safe. We’ll be all right here ’til morning.”

“Morning,” she whispers intensely. “Yes, morning. Until morning.”

I feel her warm hand around mine and clasp it tight.

After a while I hear the quiet sound of weeping in the room. For some time I fail to comprehend that the sound is coming from me.

…continued in Lullaby for the Rain Girl, now available from Dark Regions Press.

« Previous | Next »

« Previous | Next »#

February 5, 2012

Silence: A Primer

Last week I was urging a friend to see the stupendously wonderful, Golden Globe-winning, Oscar-nominated film The Artist, which, if you’ve been paying any attention at all to recent films, you know is a black-and-white silent movie—a French-made tribute of sorts to early Hollywood, a comedy-drama about a silent-era star, George Valentin, who faces career catastrophe with the coming of sound while watching new star Peppy Miller, who had appeared as a mere extra in his movies, ascend the heights of celebrity.

Yes, the story has been told before—in a sense it’s A Star is Born redux—but The Artist makes it fresh through its brilliantly original approach. It’s silent, yes, but not really silent—writer/director Michel Hazanavicius knows exactly when to use sound in this “silent” movie, to amazing effect. I found myself transfixed from first frame to last (even as it sometimes felt as if I was watching a very loose adaptation of my own book, Gilbert and Garbo in Love).

[image error]

Anyway, once I was done raving about this amazing film to my friend, he said something that brought me up short.

“I’m not sure I’m sophisticated enough for that movie,” he said.

Though the concern is misguided—I know a sixteen-year-old girl who saw the film and not only loved it, but said, “after ten minutes you forget it’s silent”—his comment did get me thinking.

I thought even more as I visited a few film sites—imdb.com, others—and looked at the online conversations about The Artist. Oh, plenty of people were raving about it, sure. But again and again I saw comments like this one:

“It’s black and white? And SILENT? NO WAY would I pay to see that!!!!!!”

I can hardly tell you how depressing I find such remarks.

The recent news story about filmgoers in England who demanded their money back upon learning that The Artist was silent is equally depressing. (Not after they’d seen the film, mind you—just after they’d learned it was silent.)

I guess such people should go back to Adam Sandler or The Green Lantern or whatever it is they think constitutes great filmmaking.

Of course matters are not helped by latter-day professional critics who increasingly dismiss silent films. Many of today’s younger critics seem almost entirely unfamiliar with silent movies, other than an obligatory viewing of Birth of a Nation and maybe a couple of comedies by Chaplin or Keaton. But even some of our most distinguished elder critics are culpable—I’m thinking here particularly of David Thomson, author of countless books on film, who—obviously trying to rationalize his indifference to silent movies—has attempted to claim that they’re not really movies at all, rejecting them as “pre-cinematic.”

I have no idea of Thomson’s opinion of The Artist, but his view of silent movies generally is utter, contemptible rubbish.

“Silent” films were never truly silent, of course—live music always accompanied them, sometimes played by a full orchestra in major cities. Live sound effects, too, were often part of the “silent” movie experience. These films are as fully cinematic as any ever made, and in some ways more so—no less an authority than Alfred Hitchcock, who got his start in the silent days, referred to them as “pure cinema,” and always strived as much as possible to minimize the dialogue in his films. (Give a look to Psycho or The Birds with this in mind sometime. There are amazingly long stretches in those movies with no dialogue at all, and the great set-pieces—the two murders in Psycho, the various attacks in The Birds—are entirely wordless.)

On matters of film, frankly, I’ll take the word of Alfred Hitchcock over that of David Thomson any day.

And yet, the obvious resistance to The Artist does point up just how disconnected many moviegoers feel from silent cinema, which to them may seem as remote as Shakespeare or Sophocles. I daresay millions of people have never seen a single silent movie in their lives (and no, Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie doesn’t count).

It’s certainly true that, given my lifelong love of the form, I walked into the theater prepared to adore The Artist, and I did. But other people may feel intimidated, like my friend—fearing they’re not “sophisticated” enough for it. On the other hand, like the girl I mentioned earlier, lots of folks may see it and love it—and suddenly find themselves curious about movies from the silent era, wanting to see some.

So, whether you want to brush up on silent films to prepare for The Artist, or, having already fallen in love with the movie, you want to see more examples of silent cinema, here are some suggestions on how to get started. These are the silent movies I think everyone should see—not to become “sophisticated,” but to simply experience some of the finest films ever made.

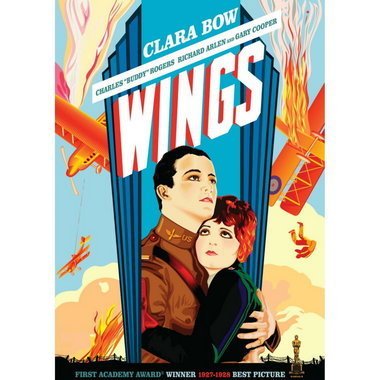

Since I mentioned the Oscars at the beginning of this, why not begin your immersion into the silent world with the first-ever Best Picture Oscar winner? Wings, from 1927, is a delightful, rip-roaring melodrama featuring Buddy Rogers, Richard Arlen and Clara Bow about two friends who enlist in the Air Corps during World War I—and the girl they leave behind (but not for long: she becomes a nurse and joins the war effort herself). Wings is as enjoyable a mass-entertainment drama as the silent era ever offered. The (authentic) aerial photography is jaw-dropping even today, the story is engrossing, and hell—Clara Bow!

Bow was the biggest female star of the period—yes, her movies made more money than Garbo’s—and this movie will leave you in no doubt as to why. Even today, Clara Bow is so vivacious, so charming, so downright sexy, that it’s impossible to take your eyes off her. If you find yourself enjoying Wings primarily for the incandescent Clara (really, Hollywood would not see her equal until the arrival of Marilyn Monroe), the movie to see next is her signature piece—1927’s It. No, not the Stephen King thriller—It is an utterly charming romantic comedy about lovelorn Clara’s desire for her handsome boss, and it earned her the title “the ‘It’ Girl” forever after. The media still regularly anoints new “‘It’ Girls,” but not one of them has been fit to shine Clara’s dancing shoes. Trust me on this…or, better yet, don’t. See Wings and It and decide for yourself.

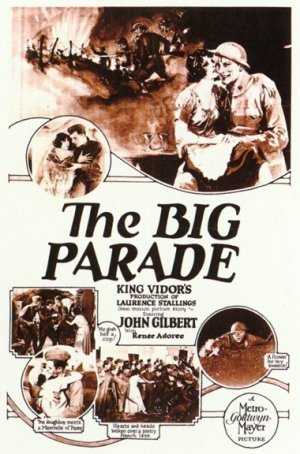

If, on the other hand, it turns out you like Wings mostly for the story, I’d strongly recommend King Vidor’s The Big Parade (1926) next—also a World War I drama, this one with John Gilbert as a foot soldier. The Big Parade is actually a better film than Wings, but in some ways it’s a little less fun—it’s actually quite grim for the most part, and has much to tell us even today about the horror and futility of war. One scene in particular, involving two soldiers in a trench—one alive, one dead—is devastating. (It was copied, almost exactly, in the early sound classic All Quiet on the Western Front.) John Gilbert is superb in The Big Parade, as is his female foil, the wonderful Renee Adoree.

Of course, any neophyte in silent cinema owes it to him/herself to take in, early and often, as much as they can of the two great early comedians, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Their names are invariably linked today, but in the silent era Chaplin was a much bigger star—the biggest star in Hollywood, in fact. In the decades since, Keaton has come to be seen as Chaplin’s equal, and fans will argue—probably until judgment day—about which one was “better.” It’s a meaningless question, because both were comedic geniuses, and the major works of both have fully stood the test of time.

For Chaplin, I recommend starting with his 1925 masterpiece The Gold Rush—but be sure to get hold of the true original film, not the 1942 reissue which Chaplin tampered with, adding a ghastly narrated soundtrack and shortening the movie by quite a bit. In The Gold Rush Chaplin, in his familiar “Little Tramp” persona, plays a prospector in the Gold Rush days. Bears, starvation, and shoe-eating ensues, to unforgettably side-splitting effect. And, as always with Chaplin’s features, there is an object to the tramp’s affections—in this case a cynical “dance hall girl” whose treatment of Charlie is heartbreaking…at first. Chaplin was the first filmmaker to successfully combine knockabout comedy with deeply emotional stories—a combination we take for granted today, but Chaplin did it first, and did it best. If you love The Gold Rush, immediately check out Chaplin’s other classics—The Kid, Modern Times, and my personal favorite, City Lights. (For that last one, bring hankies.)

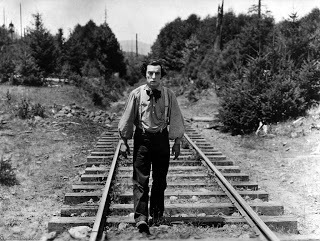

Keaton, “the Great Stone Face,” made a number of classic comedies in the ’20s, but most would agree that his Civil War epic The General (1926) is his masterpiece. This story—based loosely on a real incident—features Buster as a Southern train engineer whose train gets stolen by Northern troops. The first half of the film has Buster chasing the thieves, desperately trying to get his beloved General back—and the second half has him being chased in turn, having successfully hijacked the train back again. Keaton was a stickler for authentic period detail, and at times The General—hilarious as it is—plays almost like a Civil War docudrama. The climactic scene, in which a pursuing train attempts to cross a burning bridge, is widely believed to have been the single most expensive shot of the silent era. I won’t reveal anything more except to say that, yes, they really did it—it’s not a special effect—and your jaw will drop with amazement even as your sides hurt with laughter. If you find yourself liking Keaton, by all means continue on to Our Hospitality, College, and Steamboat Bill Jr. (The famous shot of the wall of a house crashing down on Keaton comes from this movie—he’s saved by one small window that happens to be open. The wall was real, weighed tons, and would have instantly killed him if the engineers’ measurements had been off by only a few feet. Again, it’s not a special effect.)

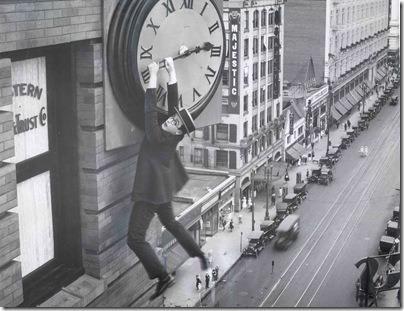

While you’re in a comedic mood, be sure check out the third of the great comedians, Harold Lloyd. He’s not as well remembered as the other two, but his great classic Safety Last is the ultimate example of his unique brand of “thrill comedy,” featuring the legendary sequence with a bespectacled Harold hanging off the arm of a giant clock. (If you’ve seen the recent Hugo, you’ve seen a brief clip of the scene.)

If you’re a fan of the aforementioned Alfred Hitchcock, by all means check out what would today be called his “breakout” film, 1926’s The Lodger. This brilliant exercise in creepiness—a handsome young man checks into a lodging house, but is he “The Avenger,” the mysterious murderer who preys on young women?—set the template for the filmmaker Hitchcock would become, and is enormously effective in its own right. Don’t miss the scene in which the characters “listen” to the footsteps of the mysterious man in the room above—said “listening” conveyed visually through the use of a glass floor, through which we can see the Lodger pacing back and forth.

Speaking of disturbing things, Broken Blossoms (1919) is a must-see—possibly the most emotionally affecting melodrama of the entire silent era. Lillian Gish plays a poverty-stricken young girl who lives with her savagely abusive father in a shack in oceanfront London. Into her life comes a gentle Chinese immigrant who shows her kindness and love—but this masterful film does not go where you think it will. D.W. Griffith, the pioneering moviemaking genius, supplies Broken Blossoms with incredibly gorgeous visuals, and this tale of interracial love is quite advanced for its time.

Despite the casual use of some unfortunate racial epithets typical of the period, and a certain degree of stereotyped ancient-wisdom-of-the-East behavior from the “Yellow man” (played well by the thoroughly un-Asian Richard Barthelmess), Broken Blossoms is a deeply humanistic film, a beautiful story beautifully told.

Enough?

I could go on, believe me.

I haven’t even gotten to Erich von Stroheim and his epic Greed, the most butchered-by-the-studio major film in movie history…and yet still one of the greatest. Or Lon Chaney, one of the finest actors ever to grace the screen—surely you should see The Phantom of the Opera, one of the most frequently revived of all silent dramas, but also a lesser-known Chaney effort called The Penalty, in which he plays—and I am not making this up—a legless gangster who gets around on little tiny crutches. It must be seen to be believed—one of the most deliriously creative, nearly surreal movies ever released by a major studio.

And how can I end without mentioning Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s vision of a future society made up of the idle rich, who live above ground in the sunshine, and the poor, who toil endlessly in factories underground? The visuals of this astonishing film have influenced every science fiction moviemaker since (after you watch Metropolis, take another look at Blade Runner), and only recently have twenty-five minutes of footage cut from the movie shortly after its release been found and reintegrated into it, giving us a more-or-less complete Metropolis for the first time since 1927.

Well, all right. Enough.

A final note. Silent films were, for the most part, poorly preserved over time, when they were preserved at all; many important movies are considered permanently lost. (My kingdom for the Theda Bara Cleopatra!) When seeking out these films on DVD, it’s important to be sure you’re getting high-quality releases—all too often what comes out from cheap public domain outfits are nothing but chopped-up, spliced, scratched, faded old prints that will quickly alienate you from the idea of ever watching another silent movie. Kino and Flicker Alley are two of the major restorers of silent films—you’ll always be in good hands with them. The major studios—MGM, 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers—release high quality products too. Basically, if you’ve never heard of the company, or the film is being offered at a suspiciously cheap price, it’s probably a low-end product that should be avoided.

In 1950 another classic tribute to Hollywood’s silent days, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, premiered. In it, the washed-up silent star Norma Desmond angrily dismisses sound movies by saying, “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces!” She was right. And that’s one of the lessons both of The Artist and of the original silent films to which it pays tribute. Pick up Wings, or The Gold Rush, or The General, or Metropolis—any of the movies I’ve mentioned. Watch how the faces tell the story. And notice how quickly you forget that you’re not hearing any dialogue.

Silent films were as legitimate a medium for telling a story as any other, and uniquely perfect for some (Chaplin’s Little Tramp is unimaginable in sound). The best of these films deserve rediscovery by wide audiences.

If you don’t believe me, just watch The Artist.

#

January 28, 2012

Earnest Art!

Click on the art itself to see it enlarged. I'll re-post the story it illustrates, "The Town Elders," below.

Artwork copyright Daryl Earnest. Visit Daryl's Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100002237918033&sk=info#!/profile.php?id=100002237918033&sk=wall

[image error] Herding Ravens

The Town Elders

copyright © Christopher Conlon

In their wisdom the town elders decreed that an ice skating rink would be built, and it was. Hundreds of happy skaters, loving couples, single men and women, teenagers, families with small wobble-walking children, came from miles around bundled in their snow clothes to enjoy gliding about on the ice under blue and white winter skies. Unfortunately the rink had been built, for reasons only the town elders might have been able to explain, over the top of a small lake, and as the weather turned from winter to spring skaters began to notice cracks which were at first no more than tiny pencil-scratches in the ice but which soon expanded to highly dangerous crevices and chasms. Skaters began to disappear under the ice into the lake, at first occasionally, and then on an alarmingly regular basis.

When blossoms began opening all over town and the weather had turned the warm of sandals and shorts, the ice rink was dismantled entirely and the same persons who had enjoyed the winter skating, that is, those who still survived, came to the lake, disrobing almost completely and allowing the sun to bronze their skin for hours on end. They ate from picnic baskets and cooked hamburgers on small barbeques. Many of them swam delightedly in the lake, paddling this way and that and playfully splashing each other. One problem, which the town elders failed entirely to solve, was that at times corpses left over from the fiasco of the skating rink would suddenly surface, and at the most inopportune times. It became an embarrassment and something of a public relations problem, never more so than when a young woman dragged a male corpse to shore, proclaiming it to be what remained of her first and indeed only true love, thereupon carrying the disintegrating thing over her shoulders to the local courthouse where she demanded that the town elders allow her to marry it. She was informed that the law did not allow for the marriage of woman to corpse, and this created a small but similarly embarrassing civil rights kerfuffle. The woman ultimately decided to cohabitate with her dearly beloved, a decision which generated some controversy in itself—but not, the town elders were certain, on the level that would have occurred had they allowed the two of them to enter into the state of holy matrimony.

One odd aspect to this entire problem of the corpses in the lake was that the lake never seemed to tire of disgorging corpses onto the shore. After a time it became embarrassingly apparent that far more deceased persons were washing up onto the sands than had vanished from the ice rink during the winter. The town elders formed a committee to study this apparently impossible problem, but no final report from this committee is known to have been issued, or if issued, it appears to have been lost.

In the meantime winter came again and the lake was once more crusted over with smooth, inviting ice. Again came the young lovers and the men and women and the families with their small wobble-walking children. But now some noticed odd round bumps appearing on the surface of the ice, bumps which slowly split the ice in places through which strange things, at first unrecognizable, began to grow. Some persons believed that the growths might be some new strain of cauliflower or tomato, but soon enough it became apparent that the growths were in fact human beings. One would see the clear ice-encrusted outlines of a forehead, a temple, a set of ears, frost-filled strands of hair. This for the town elders was the ultimate humiliation, and it was quickly decided that something would have to be done. Fortunately there was a course of action readily and even obviously available to them, and they took it. The town elders began to cultivate this unprecedented winter crop. One would see them late at night in their heavy coats tilling the ice rink with shovels and hoes, always careful to smooth the ice again after pulling nature’s peculiar yield from the ice. Eventually the story, which was true, went around that the crops were in fact delicious to eat when prepared properly, and soon the townspeople themselves were tending what was now less a skating rink than a glorious winter garden. Neighbors laughed and joked about this unexpected bounty and exchanged recipes enthusiastically. If you ever decide to go to the town, by all means do so in the depths of winter. Buy one of the readily-available cookbooks for sale at various shops near the garden. And then go and collect some winter crops for your own dinner. There’s more than enough for everyone. Indeed, the supply is ample and even, at times, overwhelming. The heads of teenage girls are said to be especially succulent when stewed for several hours with carrot and onion in chicken stock. Or snap off some baby fingers, which are simple to gather and requite no preparation at all. The town elders assure us that they are delicious straight from the ice, sweet and with an unexpected tanginess.

#

January 13, 2012

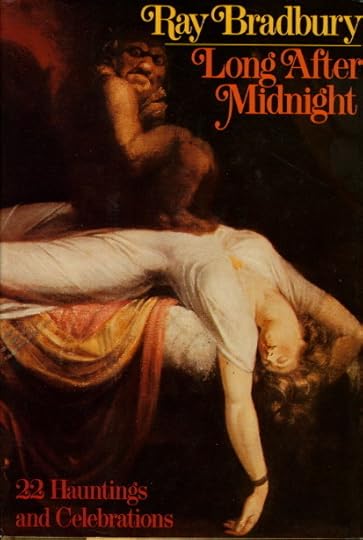

Long After "Long After Midnight": Bradbury Reconsidered

Not long ago, in a moment of minor personal crisis, I found myself hungering after the literary equivalent of comfort food.

Something familiar, but not too familiar—not familiar to the point of boredom. Yet something that would give me a predictably pleasant lift.

Wandering our basement library (which contains some 3000 of those bulky pre-Kindle items earlier generations called “books”), I came across the perfect thing: a copy of Long After Midnight by Ray Bradbury.

But not just any copy. My Long After Midnight is the first edition, published by Knopf, and in fact, it’s the first brand-new hardcover I ever bought. The book is in very good condition, and the dust jacket is nearly perfect, having had a Brodart jacket protector applied to it a few years later, when I was in college and began doing such things.

The price indicated on the front jacket flap, $7.95, raises a smile with me today. The back flap reads “9/76,” and that’s about right: I have a feeling that I purchased the volume shortly after my fourteenth birthday, around the time I entered high school. Most likely I did so with some birthday money (I’m an August baby). I can remember being in the bookstore, which was on State Street in downtown Santa Barbara, though the name of the shop has vanished from my memory. I recall how special I felt, picking up from the display table such an expensive item, a brand-new hardcover book, and taking it to the counter to pay for it. My dad was with me, which is further evidence that this must have been birthday-related: my father wouldn’t have been caught dead in a bookstore otherwise.

I owned hardcover books already, of course, but they were of two varieties: 1) thrift-store purchases, a quarter for, say, a beat-up old Perry Mason novel; or, 2) book-club reprints, received in the mail and, I’d begun to recognize by comparing them to the editions found in the local library, distinctly cheap in their paper and bindings. By the time I was thirteen or so I understood the difference between a cruddy book-club job and a real publisher’s edition.

I no longer recall how I discovered the work of Ray Bradbury but, like many young kids with a burgeoning love for the “dark fantastic,” I went through a major phase of reading him—he was one of the main conduits in my transitioning from reading mostly books my mother liked (primarily mysteries, Ed McBain and Dell Shannon) and striking out on my own, into unknown territories. Childhood is, of course, the ideal time to discover Bradbury’s work (and science fiction/fantasy in general), and I fell thoroughly in love with this master of plot and prose through the usual channels: The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451, The Illustrated Man, S is for Space, R is for Rocket.

Long After Midnight, then, has retained a special place in my collection, and it has another significance as well—it was also the first book I ever got signed by its author. This happened in 1983, at Santa Barbara’s Andromeda Bookstore. I remember little of the event except that the line was long, customers were limited to one book each, and I was surprised when I finally made my way to the front to see how puffy and red-faced Mr. Bradbury looked. It was suddenly obvious to me that the author photos on his books were some years out of date.

I would love to be able to report that this one-time meeting between a present literary titan and a future one was a memorable exchange of witticisms or profound philosophical ideas, but in fact what it amounted to was a nervous young fellow who simply pushed his book toward The Great Man and said, “Hi,” to which said Great Man responded memorably, “Hi.” He signed the book with a big purple marker, adding the date: “6/18/83.”

He handed the book back to me. I said, “Thank you.”

And that was it.

Oh, well.

Still, though the book has had a proud place on my shelves for decades, I realized something as I pulled it down recently, searching for that literary comfort food.

I had not actually read this book since I bought it way back in 1976.

Read it all the way through, I mean. It has certainly come off the shelf now and then over the years, and I’ve poked around in it. One or two of the stories therein are among my favorites by Bradbury; I’ve read them many times, even taught them. But I’d never revisited the vast majority of the tales in Long After Midnight. I had no memory of what most of them were about.

My search for literary comfort food was over.

In the next couple of days I re-read Long After Midnight straight through. It proved to be an odd experience—exhilarating at times, exciting, amusing, sometimes disappointing, and occasionally downright baffling.

For Long After Midnight is later Bradbury, not the Bradbury of the early classics. This often seems to be something considered almost unmentionable, but the truth is, like many first-rank artists, Ray Bradbury had a finite period of greatness. It began in the mid-1940s, as he commenced writing his initial series of peerless horror tales (“The Small Assassin,” “The Emissary,” countless others), and ended in the mid-1950s—say the late 1950s, if one wants to be generous. Everything that followed proved to be mere postscript.

If that sounds unnecessarily harsh, it isn’t meant to be; I’m in no way saying that Bradbury has written nothing of quality in the past half-century. But literary genius does tend to have an expiration date. Yes, Henry James managed to have an early, middle, and late period, and created masterpieces in all of them; but far more common is the writer who burns brightly for a few years and then sinks back into lesser work. Ernest Hemingway is a classic example of the phenomenon. So is my favorite playwright in the world, Tennessee Williams, whose great period exactly coincided with Bradbury’s. Arthur Miller, too. In fact, most writers with major reputations and long careers build those reputations in relatively brief periods when they create the works by which they will be remembered.

Ray Bradbury will not be remembered by the material in Long After Midnight, but the strengths and weaknesses of the volume seem to me to reveal much about Bradbury as a writer.

There are twenty-two stories in Long After Midnight. Here is the Table of Contents:

The Blue Bottle

One Timeless Spring

The Parrot Who Met Papa

The Burning Man

A Piece of Wood

The Messiah

G.B.S.—Mark V

The Utterly Perfect Murder

Punishment Without Crime

Getting Through Sunday Somehow

Drink Entire: Against the Madness of Crowds

Interval in Sunlight

A Story of Love

The Wish

Forever and the Earth

The Better Part of Wisdom

Darling Adolf

The Miracles of Jamie

The October Game

The Pumpernickel

Long After Midnight

Have I Got a Chocolate Bar For You!

When reading through this collection it’s frequently obvious, even without looking up the copyright dates, which stories were new to this mid-’70s volume and which were leftover tales from his earlier period. Long After Midnight begins with “The Blue Bottle,” a curious choice, since it’s clearly an old one (from 1950, in fact), and not especially strong. The main appeal of the tale is that it reads almost like a story cut from The Martian Chronicles. On the dead Mars of the future two Earthmen, Craig and Beck, search for the possibly mythological “blue bottle,” made by Martians of Martian glass, and said to have the ability to grant its holder any wish. The story’s setting is not quite that of The Martian Chronicles—mention is made of how, after the First Industrial Invasion of Mars, the human race “moved on toward the stars.” But the description of the fragile glass cities and the ancient Martian civilization can’t help but toss anyone familiar with the Chronicles back to that world:

“Under the cool double moons of Mars the midnight cities were bone and dust. Along the scattered highway the landcar bumped and rattled, past cities where the fountains, the gyrostats, the furniture, the metal-singing books, the painting lay powdered over with mortar and insect wings. Past cities that were cities no longer, but only things rubbed to a fine silt that flowed senselessly back and forth on the wine winds between one land and another, like the sand in a gigantic hourglass, endlessly pyramiding and repyramiding.”

The narrative voice is unmistakable, and “The Blue Bottle” is beautifully written; but in the end it’s clear enough why Bradbury didn’t make a few simple adjustments to the tale and retrofit it into The Martian Chronicles. It just isn’t that memorable. As a result, Long After Midnight kicks off on an odd note, a nostalgic one, but not one all that lasting. (This is doubly puzzling because for some reason, later in the book appears one of Bradbury’s best-known horror tales, “The October Game”—it would have made a far more powerful opening. But it’s strange that this oft-anthologized tale is there at all; it’s the only well-known story in the collection, and even in 1976 was available in many other places.)

But it’s when we get to the current stories, those written in the latter ’60s and early ’70s, that Long After Midnight gets into some of its deepest trouble.

Mind you, there are good stories among the later ones here. “The Utterly Perfect Murder” is a gem, a tale of a middle-aged man who returns to his home town to settle an old score and is horrified by what he finds there. “Punishment Without Crime” is also very good, a virtual sequel to Bradbury’s famous “Marionettes, Inc.,” in which a man “murders” a perfect replica of his wife—a replica created for exactly that purpose—and then discovers things working out quite differently from what he’d expected. “Interval in Sunlight,” the longest story in the book, is an incisive and disturbing psychological study of what today would be called a codependent relationship—a marriage in which abuser and abused seem hopelessly locked together for all time.

But many of the later efforts suffer from the usual problems of Bradbury’s post-1950s writing—slight story concepts, sloppy sentimentality, overworked metaphors, overwrought prose. Nowhere are these difficulties more obvious than in “A Story of Love” (a tale whose bad title tells you something important about what’s to follow). This effort is set in Bradbury’s legendary Green Town, and details the burgeoning love of schoolboy Bob Spaulding for his new teacher, Ann Taylor—and, perhaps, her love for him. (Don’t worry; this being Bradbury in his sentimental mode, nothing icky will happen.) The story opens with…well, allow me to simply quote the second paragraph:

“Everyone remembered Ann Taylor, for she was that teacher for whom all the children wanted to bring huge oranges or pink flowers, and for whom they rolled up the rustling green and yellow maps of the world without being asked. She was that woman who always seemed to be passing by on days when the shade was green under the tunnel of oaks and elms in the old town, her face shifting with the bright shadows as she walked, until it was all things to all people. She was the fine peaches of summer in the snow of winter, and she was cool milk for cereal on a hot early-June morning. Whenever you needed an opposite, Ann Taylor was there. And those rare few days in the world when the climate was balanced as fine as a maple leaf between winds that blew just right, those were the days like Ann Taylor, and should have been so named on the calendar.”

Whoo, boy.

There are several words I can think of to describe this kind of prose. One would be “purple.” Another: “fey.” A third: “Please-stop-writing-like-this-or-I-will-start-screaming.”

Okay, I cheated on that last one.

Alas, this kind of flowery, pseudo-lyrical balderdash mars many of the stories in Long After Midnight, and reminds me why I stopped reading Bradbury’s newer work many years ago. The Bradbury of the early 1950s would never have allowed many of these stories into print, or at least he would have excised much of the windy emptiness of the prose.

I don’t know what I thought of such prose then, in 1976, when I took the volume home and read it cover to cover. I remember that I was disappointed with the book as a whole, even as I liked some of the individual stories: overall, it didn’t seem a waste of my $7.95-plus-tax, even as I recognized that it was a far cry from the great Bradbury books I’d previously encountered. A few of the stories, like the aforementioned “Interval in Sunlight,” must have gone over my head—I doubt I understood much of what Bradbury was writing about. Others contained references I couldn’t possibly have grasped, as with “G.B.S.—Mark V,” about a robot George Bernard Shaw, or “Forever and the Earth,” about a space-age resurrection of Thomas Wolfe. I’m quite sure I’d never heard of those people then, and as a result Bradbury’s tributes to them couldn’t have meant anything to me.

But other stories, many of them, failed for me then for the same reasons they fail today: Slightness, soppiness, overwriting to the point of absurdity. One more painful example will suffice, this from “The Better Part of Wisdom”—and keep in mind as you read it that this is actually appears in the dialogue. Yes, a human being is supposed to be saying these words, in which an old man remembers a brief childhood friendship:

“We walked the shore, and that’s all there was, the simple thing of us upon the shore, and building castles or climbing hills to fight wars among the mounds. We found an old round tower and yelled up and down from it. But mostly it was walking, our arms around each other like twins born in a tangle, never cut free by knife or lightning. I inhaled, he exhaled. Then he breathed and I was the sweet chorus…We found ourselves laid out with sweet hilarity, eyes tight, gripped to each other’s shaking, and the laugh jumped free like one silver trout following another. God, I bathed in his laughter as he bathed in mine, until we were weak as if love had put us to the slaughter and exhaustions. We panted then like pups in hot summer, empty of laughing, and sleepy with friendship. And the weather for that week was blue and gold, no clouds, no rain, and a wind that smelled of apples, but no, only that boy’s wild breath.”

Yep…okay.

I read somewhere that when W.H. Auden was unhappy with something he read, he would tell the author: “I’m sorry, my dear, but it won’t do.”

This writing won’t do.

Then, to be perfectly honest—and I know this will be sacrilege to some—I have never liked or responded to Bradbury’s writings about children. Again and again when reading books like Dandelion Wine and Something Wicked This Way Comes I find myself shaking my head in disbelief at how the children are portrayed. (For a quick refresher course in the weird unreality of Bradbury’s child characters, take a gander at the 1980s movie adaptation of Something Wicked, which he scripted. One cannot envy the lot of the kids in the film who were made to utter that dialogue.) No, it won’t do. Children don’t think like that, they don’t talk like that, they don’t act like that. The children in Bradbury’s stories aren’t children, they are a grown man’s gauzy and rose-colored recollection of what it is to be a child. It rings false every time, just as those lines from “The Better Part of Wisdom” do.

Other stories in Long After Midnight, while not filled with the kind of wild rhetorical buzzkill I’ve just quoted, are poor simply because they’re so slight, so trivial. “Darling Adolf,” “The Miracles of Jamie,” and “Have I Got a Chocolate Bar For You!” fit into this camp, tales so flimsy that one wonders why Bradbury bothered to write them and, having written them, why he bothered to publish them.

And yet there are also moments in Long After Midnight which amaze and exhilarate.

“The Burning Man” is another gem, a brief story which asks “if there is such a thing as genetic evil in the world,” and delivers a memorably ghastly answer. (This story was adapted, and quite well, into one of the few worthwhile segments of the 1980s Twilight Zone revival series.)

“The Pumpernickel” is a lovely, low-key tale about a man’s memories which reminds me of some of Bernard Malamud’s classic short works.

And then there is the title story, which is both grim and unforgettable. “Long After Midnight” opens with several policemen and paramedics at a cliff, where they make a grisly discovery:

“The slender weight was a girl, no more than nineteen, in a light green gossamer party frock, coat and shoes lost somewhere in the cool night, who had brought a rope up to these cliffs and found a tree with a branch half over the cliff and tied the rope in place and made a loop for her neck and let herself out on the wind to hang there swinging. The rope made a dry scraping whine on the branch, until the police came, and the ambulance, to take her down out of space and place her on the ground.”

These grizzled professionals speculate a bit about the girl as they cut her down, load her dead body into the ambulance, and drive off into the night toward the morgue. Little else happens in the story.

…Little else, that is, except a final sudden revelation which changes—or possibly does not change—the men’s entire perspective, and ours, on what has happened, and what it means.

When I got to the end of this powerful and indescribably moving tale back in 1976, when I was all of fourteen, I knew I’d read something I would never forget. And I never have. “Long After Midnight,” the story, made me think differently about some very important things in life and society.

What things?

Well, you’ll have to read the story for yourself.

And so in Long After Midnight, the collection, Bradbury’s magic still works, if only sputteringly, sporadically. Thirty-five years later, I’ve discovered that I was both very wrong about these stories and very right: the worst are worse than I remembered, the best better than I’d dared hope.

In any event, this volume of literary comfort food—my first new hardcover, my first signed book—will, barring fire or flood, retain its place of honor in the basement library until, I suppose, my dying day. I don’t know if I’ll ever read it straight through again. But from time to time I’ll bring it down from the shelves and find my way to the pages, and there are many of them, that let me remember Bradbury as he once was—and, by 1976, still occasionally could be.

#