Silence: A Primer

Last week I was urging a friend to see the stupendously wonderful, Golden Globe-winning, Oscar-nominated film The Artist, which, if you’ve been paying any attention at all to recent films, you know is a black-and-white silent movie—a French-made tribute of sorts to early Hollywood, a comedy-drama about a silent-era star, George Valentin, who faces career catastrophe with the coming of sound while watching new star Peppy Miller, who had appeared as a mere extra in his movies, ascend the heights of celebrity.

Yes, the story has been told before—in a sense it’s A Star is Born redux—but The Artist makes it fresh through its brilliantly original approach. It’s silent, yes, but not really silent—writer/director Michel Hazanavicius knows exactly when to use sound in this “silent” movie, to amazing effect. I found myself transfixed from first frame to last (even as it sometimes felt as if I was watching a very loose adaptation of my own book, Gilbert and Garbo in Love).

[image error]

Anyway, once I was done raving about this amazing film to my friend, he said something that brought me up short.

“I’m not sure I’m sophisticated enough for that movie,” he said.

Though the concern is misguided—I know a sixteen-year-old girl who saw the film and not only loved it, but said, “after ten minutes you forget it’s silent”—his comment did get me thinking.

I thought even more as I visited a few film sites—imdb.com, others—and looked at the online conversations about The Artist. Oh, plenty of people were raving about it, sure. But again and again I saw comments like this one:

“It’s black and white? And SILENT? NO WAY would I pay to see that!!!!!!”

I can hardly tell you how depressing I find such remarks.

The recent news story about filmgoers in England who demanded their money back upon learning that The Artist was silent is equally depressing. (Not after they’d seen the film, mind you—just after they’d learned it was silent.)

I guess such people should go back to Adam Sandler or The Green Lantern or whatever it is they think constitutes great filmmaking.

Of course matters are not helped by latter-day professional critics who increasingly dismiss silent films. Many of today’s younger critics seem almost entirely unfamiliar with silent movies, other than an obligatory viewing of Birth of a Nation and maybe a couple of comedies by Chaplin or Keaton. But even some of our most distinguished elder critics are culpable—I’m thinking here particularly of David Thomson, author of countless books on film, who—obviously trying to rationalize his indifference to silent movies—has attempted to claim that they’re not really movies at all, rejecting them as “pre-cinematic.”

I have no idea of Thomson’s opinion of The Artist, but his view of silent movies generally is utter, contemptible rubbish.

“Silent” films were never truly silent, of course—live music always accompanied them, sometimes played by a full orchestra in major cities. Live sound effects, too, were often part of the “silent” movie experience. These films are as fully cinematic as any ever made, and in some ways more so—no less an authority than Alfred Hitchcock, who got his start in the silent days, referred to them as “pure cinema,” and always strived as much as possible to minimize the dialogue in his films. (Give a look to Psycho or The Birds with this in mind sometime. There are amazingly long stretches in those movies with no dialogue at all, and the great set-pieces—the two murders in Psycho, the various attacks in The Birds—are entirely wordless.)

On matters of film, frankly, I’ll take the word of Alfred Hitchcock over that of David Thomson any day.

And yet, the obvious resistance to The Artist does point up just how disconnected many moviegoers feel from silent cinema, which to them may seem as remote as Shakespeare or Sophocles. I daresay millions of people have never seen a single silent movie in their lives (and no, Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie doesn’t count).

It’s certainly true that, given my lifelong love of the form, I walked into the theater prepared to adore The Artist, and I did. But other people may feel intimidated, like my friend—fearing they’re not “sophisticated” enough for it. On the other hand, like the girl I mentioned earlier, lots of folks may see it and love it—and suddenly find themselves curious about movies from the silent era, wanting to see some.

So, whether you want to brush up on silent films to prepare for The Artist, or, having already fallen in love with the movie, you want to see more examples of silent cinema, here are some suggestions on how to get started. These are the silent movies I think everyone should see—not to become “sophisticated,” but to simply experience some of the finest films ever made.

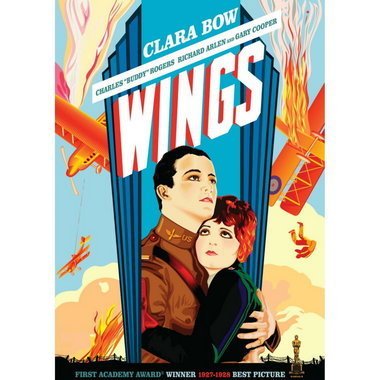

Since I mentioned the Oscars at the beginning of this, why not begin your immersion into the silent world with the first-ever Best Picture Oscar winner? Wings, from 1927, is a delightful, rip-roaring melodrama featuring Buddy Rogers, Richard Arlen and Clara Bow about two friends who enlist in the Air Corps during World War I—and the girl they leave behind (but not for long: she becomes a nurse and joins the war effort herself). Wings is as enjoyable a mass-entertainment drama as the silent era ever offered. The (authentic) aerial photography is jaw-dropping even today, the story is engrossing, and hell—Clara Bow!

Bow was the biggest female star of the period—yes, her movies made more money than Garbo’s—and this movie will leave you in no doubt as to why. Even today, Clara Bow is so vivacious, so charming, so downright sexy, that it’s impossible to take your eyes off her. If you find yourself enjoying Wings primarily for the incandescent Clara (really, Hollywood would not see her equal until the arrival of Marilyn Monroe), the movie to see next is her signature piece—1927’s It. No, not the Stephen King thriller—It is an utterly charming romantic comedy about lovelorn Clara’s desire for her handsome boss, and it earned her the title “the ‘It’ Girl” forever after. The media still regularly anoints new “‘It’ Girls,” but not one of them has been fit to shine Clara’s dancing shoes. Trust me on this…or, better yet, don’t. See Wings and It and decide for yourself.

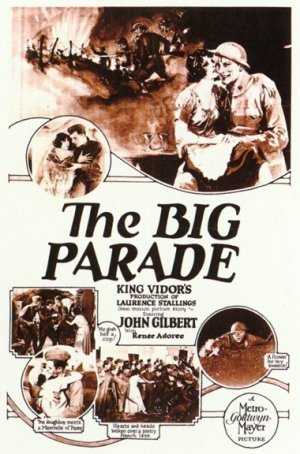

If, on the other hand, it turns out you like Wings mostly for the story, I’d strongly recommend King Vidor’s The Big Parade (1926) next—also a World War I drama, this one with John Gilbert as a foot soldier. The Big Parade is actually a better film than Wings, but in some ways it’s a little less fun—it’s actually quite grim for the most part, and has much to tell us even today about the horror and futility of war. One scene in particular, involving two soldiers in a trench—one alive, one dead—is devastating. (It was copied, almost exactly, in the early sound classic All Quiet on the Western Front.) John Gilbert is superb in The Big Parade, as is his female foil, the wonderful Renee Adoree.

Of course, any neophyte in silent cinema owes it to him/herself to take in, early and often, as much as they can of the two great early comedians, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Their names are invariably linked today, but in the silent era Chaplin was a much bigger star—the biggest star in Hollywood, in fact. In the decades since, Keaton has come to be seen as Chaplin’s equal, and fans will argue—probably until judgment day—about which one was “better.” It’s a meaningless question, because both were comedic geniuses, and the major works of both have fully stood the test of time.

For Chaplin, I recommend starting with his 1925 masterpiece The Gold Rush—but be sure to get hold of the true original film, not the 1942 reissue which Chaplin tampered with, adding a ghastly narrated soundtrack and shortening the movie by quite a bit. In The Gold Rush Chaplin, in his familiar “Little Tramp” persona, plays a prospector in the Gold Rush days. Bears, starvation, and shoe-eating ensues, to unforgettably side-splitting effect. And, as always with Chaplin’s features, there is an object to the tramp’s affections—in this case a cynical “dance hall girl” whose treatment of Charlie is heartbreaking…at first. Chaplin was the first filmmaker to successfully combine knockabout comedy with deeply emotional stories—a combination we take for granted today, but Chaplin did it first, and did it best. If you love The Gold Rush, immediately check out Chaplin’s other classics—The Kid, Modern Times, and my personal favorite, City Lights. (For that last one, bring hankies.)

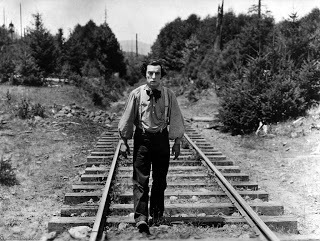

Keaton, “the Great Stone Face,” made a number of classic comedies in the ’20s, but most would agree that his Civil War epic The General (1926) is his masterpiece. This story—based loosely on a real incident—features Buster as a Southern train engineer whose train gets stolen by Northern troops. The first half of the film has Buster chasing the thieves, desperately trying to get his beloved General back—and the second half has him being chased in turn, having successfully hijacked the train back again. Keaton was a stickler for authentic period detail, and at times The General—hilarious as it is—plays almost like a Civil War docudrama. The climactic scene, in which a pursuing train attempts to cross a burning bridge, is widely believed to have been the single most expensive shot of the silent era. I won’t reveal anything more except to say that, yes, they really did it—it’s not a special effect—and your jaw will drop with amazement even as your sides hurt with laughter. If you find yourself liking Keaton, by all means continue on to Our Hospitality, College, and Steamboat Bill Jr. (The famous shot of the wall of a house crashing down on Keaton comes from this movie—he’s saved by one small window that happens to be open. The wall was real, weighed tons, and would have instantly killed him if the engineers’ measurements had been off by only a few feet. Again, it’s not a special effect.)

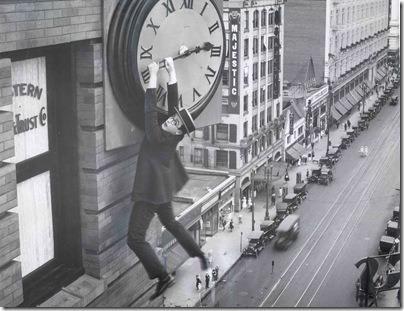

While you’re in a comedic mood, be sure check out the third of the great comedians, Harold Lloyd. He’s not as well remembered as the other two, but his great classic Safety Last is the ultimate example of his unique brand of “thrill comedy,” featuring the legendary sequence with a bespectacled Harold hanging off the arm of a giant clock. (If you’ve seen the recent Hugo, you’ve seen a brief clip of the scene.)

If you’re a fan of the aforementioned Alfred Hitchcock, by all means check out what would today be called his “breakout” film, 1926’s The Lodger. This brilliant exercise in creepiness—a handsome young man checks into a lodging house, but is he “The Avenger,” the mysterious murderer who preys on young women?—set the template for the filmmaker Hitchcock would become, and is enormously effective in its own right. Don’t miss the scene in which the characters “listen” to the footsteps of the mysterious man in the room above—said “listening” conveyed visually through the use of a glass floor, through which we can see the Lodger pacing back and forth.

Speaking of disturbing things, Broken Blossoms (1919) is a must-see—possibly the most emotionally affecting melodrama of the entire silent era. Lillian Gish plays a poverty-stricken young girl who lives with her savagely abusive father in a shack in oceanfront London. Into her life comes a gentle Chinese immigrant who shows her kindness and love—but this masterful film does not go where you think it will. D.W. Griffith, the pioneering moviemaking genius, supplies Broken Blossoms with incredibly gorgeous visuals, and this tale of interracial love is quite advanced for its time.

Despite the casual use of some unfortunate racial epithets typical of the period, and a certain degree of stereotyped ancient-wisdom-of-the-East behavior from the “Yellow man” (played well by the thoroughly un-Asian Richard Barthelmess), Broken Blossoms is a deeply humanistic film, a beautiful story beautifully told.

Enough?

I could go on, believe me.

I haven’t even gotten to Erich von Stroheim and his epic Greed, the most butchered-by-the-studio major film in movie history…and yet still one of the greatest. Or Lon Chaney, one of the finest actors ever to grace the screen—surely you should see The Phantom of the Opera, one of the most frequently revived of all silent dramas, but also a lesser-known Chaney effort called The Penalty, in which he plays—and I am not making this up—a legless gangster who gets around on little tiny crutches. It must be seen to be believed—one of the most deliriously creative, nearly surreal movies ever released by a major studio.

And how can I end without mentioning Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s vision of a future society made up of the idle rich, who live above ground in the sunshine, and the poor, who toil endlessly in factories underground? The visuals of this astonishing film have influenced every science fiction moviemaker since (after you watch Metropolis, take another look at Blade Runner), and only recently have twenty-five minutes of footage cut from the movie shortly after its release been found and reintegrated into it, giving us a more-or-less complete Metropolis for the first time since 1927.

Well, all right. Enough.

A final note. Silent films were, for the most part, poorly preserved over time, when they were preserved at all; many important movies are considered permanently lost. (My kingdom for the Theda Bara Cleopatra!) When seeking out these films on DVD, it’s important to be sure you’re getting high-quality releases—all too often what comes out from cheap public domain outfits are nothing but chopped-up, spliced, scratched, faded old prints that will quickly alienate you from the idea of ever watching another silent movie. Kino and Flicker Alley are two of the major restorers of silent films—you’ll always be in good hands with them. The major studios—MGM, 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers—release high quality products too. Basically, if you’ve never heard of the company, or the film is being offered at a suspiciously cheap price, it’s probably a low-end product that should be avoided.

In 1950 another classic tribute to Hollywood’s silent days, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, premiered. In it, the washed-up silent star Norma Desmond angrily dismisses sound movies by saying, “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces!” She was right. And that’s one of the lessons both of The Artist and of the original silent films to which it pays tribute. Pick up Wings, or The Gold Rush, or The General, or Metropolis—any of the movies I’ve mentioned. Watch how the faces tell the story. And notice how quickly you forget that you’re not hearing any dialogue.

Silent films were as legitimate a medium for telling a story as any other, and uniquely perfect for some (Chaplin’s Little Tramp is unimaginable in sound). The best of these films deserve rediscovery by wide audiences.

If you don’t believe me, just watch The Artist.

#