Cameron Conaway's Blog - Posts Tagged "mindfulness"

Screen time

Imagine a new kind of screen time, one where your inner thoughts are displayed on a real-time billboard for all to see. Would you be proud of how you think about yourself?

The distractions of today make it easier than ever to neglect three critical aspects of understanding our inner worlds:

1) getting distance from our thoughts to realize we are not our thoughts;

2) reflecting on our thoughts to recognize patterns, especially negative refrains; and,

3) developing mental habits that serve rather than hinder our goals.

To take back control we must recognize thoughts for what they are—projections onto our internal billboards. Yes, they may be comprised of a dizzying area of complex experiences and signals, but a newfound strength can arise when we realize we are the projector not the projected.

The distractions of today make it easier than ever to neglect three critical aspects of understanding our inner worlds:

1) getting distance from our thoughts to realize we are not our thoughts;

2) reflecting on our thoughts to recognize patterns, especially negative refrains; and,

3) developing mental habits that serve rather than hinder our goals.

To take back control we must recognize thoughts for what they are—projections onto our internal billboards. Yes, they may be comprised of a dizzying area of complex experiences and signals, but a newfound strength can arise when we realize we are the projector not the projected.

Published on January 13, 2020 08:08

•

Tags:

mental, mindfulness, strength, thinking

How we work our ladder

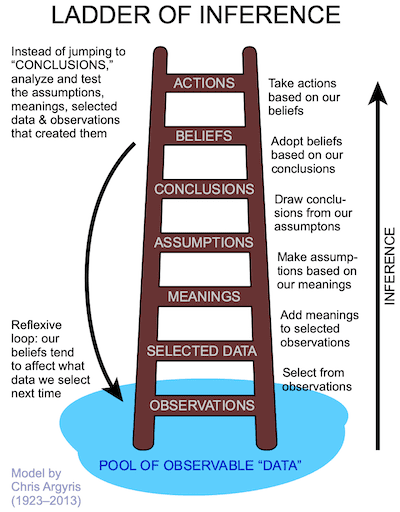

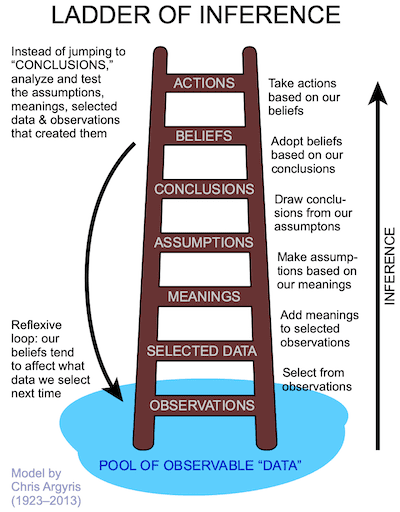

We’re hardwired to judge and quickly make decisions. Today, however, it could be argued that this hardwiring is more of a detriment than a benefit. Too often, we gather questionable data, believe in it because it fits our pre-existing biases, and then seek out additional questionable data that validates this belief.

The late Chris Argyris, a former Harvard Business School professor, developed the “ladder of inference” to describe the process of our mental reasoning. It looks like this:

While running from predators or assessing the potential for violence of a nearby tribe are no longer priorities for most of us, we’re still prone to walk up and down the ladder far too quickly. This can result not only in miscommunication and broken relationships, but also in the development of increasingly extreme positions—something many of today’s politicians love to exploit.

The next time you find yourself judging or “knowing” something too quickly, first thank yourself for recognizing what happened, then ask yourself where you are on the ladder.

Note: for a more in-depth read on the ladder of inference, check out The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization.

The late Chris Argyris, a former Harvard Business School professor, developed the “ladder of inference” to describe the process of our mental reasoning. It looks like this:

While running from predators or assessing the potential for violence of a nearby tribe are no longer priorities for most of us, we’re still prone to walk up and down the ladder far too quickly. This can result not only in miscommunication and broken relationships, but also in the development of increasingly extreme positions—something many of today’s politicians love to exploit.

The next time you find yourself judging or “knowing” something too quickly, first thank yourself for recognizing what happened, then ask yourself where you are on the ladder.

Note: for a more in-depth read on the ladder of inference, check out The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization.

Published on January 15, 2020 08:55

•

Tags:

mindfulness, reasoning, thinking

Transforming the second arrow

In Buddhist literature, the second arrow refers to the controllable negative states of mind that can arise due to the suffering caused by the more or less uncontrollable first arrow.

We've all been caught in the throes of the second arrow. Here are a few personal examples. Try to plug relatable details of your stories into mine.

As the featured speaker at an event about masculinity, I made a thoughtless statement that both hurt me immediately after I said it and landed badly with the crowd. I knew better, but the words were now out in the world. There was no going back. That was the first arrow.

The second arrow followed swiftly after that in the form of my mind judging my performance as I was performing. Rather than having the presence of mind to acknowledge the mistake publicly and confidently move on, I became trapped in my inner world—at once trying to deliver a riveting speech while fending off a constant internal voice belittling my performance.

It was the second arrow, not the first, that rattled me into ultimately underdelivering for my audience.

The second arrow also struck when I lost my third mixed martial arts fight. The first arrow, for me, was the loss. I had trained for years and felt the sting of defeat.

The second arrow lasted for months as I harshly blamed myself for letting down so many people who had supported me. As with the speaking example, rather than feeling the initial sting of the loss and then pivoting to see it as a learning opportunity and as a chance to show gratitude to my supporters, I turned inward and sunk into a depression as the second arrow of blame and regret grew deeper.

If you think about it, there have likely been times in your life when a significant portion of your inner voice was the language of the second arrow. Over time, through meditation and other contemplative practices, we can build a self-awareness strong enough to recognize the second arrow as it's hurtling toward us.

The end goal, however, isn't to mask the second arrow or dwell in our self-awareness; it's to nurture our self-awareness so we can move from recognizing the second arrow mid-flight to positively transforming what it becomes.

We've all been caught in the throes of the second arrow. Here are a few personal examples. Try to plug relatable details of your stories into mine.

As the featured speaker at an event about masculinity, I made a thoughtless statement that both hurt me immediately after I said it and landed badly with the crowd. I knew better, but the words were now out in the world. There was no going back. That was the first arrow.

The second arrow followed swiftly after that in the form of my mind judging my performance as I was performing. Rather than having the presence of mind to acknowledge the mistake publicly and confidently move on, I became trapped in my inner world—at once trying to deliver a riveting speech while fending off a constant internal voice belittling my performance.

It was the second arrow, not the first, that rattled me into ultimately underdelivering for my audience.

The second arrow also struck when I lost my third mixed martial arts fight. The first arrow, for me, was the loss. I had trained for years and felt the sting of defeat.

The second arrow lasted for months as I harshly blamed myself for letting down so many people who had supported me. As with the speaking example, rather than feeling the initial sting of the loss and then pivoting to see it as a learning opportunity and as a chance to show gratitude to my supporters, I turned inward and sunk into a depression as the second arrow of blame and regret grew deeper.

If you think about it, there have likely been times in your life when a significant portion of your inner voice was the language of the second arrow. Over time, through meditation and other contemplative practices, we can build a self-awareness strong enough to recognize the second arrow as it's hurtling toward us.

The end goal, however, isn't to mask the second arrow or dwell in our self-awareness; it's to nurture our self-awareness so we can move from recognizing the second arrow mid-flight to positively transforming what it becomes.

Published on January 16, 2020 10:17

•

Tags:

mindfulness, second-arrow, self-awareness

The ripple effect of wise speech

Last year, I attended a workshop led by Donald Rothberg about cultivating wise speech. A meditation teacher for over 35 years, Rothberg’s communication style was an embodiment of the lessons he shared.

At its core, wise speech is about practicing this vow from Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh:

“Aware of the suffering caused by unmindful speech and the inability to listen to others, I vow to cultivate loving speech and deep listening….”

Rothberg shared many insights and practical strategies, including the Four Guidelines for Wise Speech, which have since become a habit (as well as sticky notes posted on the wall above my work computer). They are as follows:

1. Truthfulness

2. Helpfulness

3. Kindness

4. Clear Intention (including good timing, appropriateness, non-distractedness)

The key here is more about consistent practice than discovering your take on the word-level meanings (although that is important).

Many of my work calls take place via computer-to-computer video conversations. Right before each call, I take a few deep breaths and then spend 10-20 seconds internalizing each guideline.

As seemingly insignificant as that sounds, this time allows me to check-in with how I’m feeling—a critical first step to ensuring that my inner suffering (such as unrelated negativity or frustration, for example) doesn’t manifest in some form that causes suffering for the recipient. Wise speech is all about entering into conversations with our best and most authentic intention—which demands feeling our feelings, not faking kindness.

Herein lies part of the ripple effect: I didn’t realize how good the practice of wise speech would make me feel as it’s happening. Before developing this practice, I thought wise speech was mostly a way to improve the life of the recipient.

The ripple continues from there, as my now outwardly projected inner sense of awareness and well-being is absorbed by the recipient who then (as I’ve been told now on several occasions) extends that energy into their next interaction.

It’s a glimpse into what Thich Nhat Hanh refers to as interbeing, a concept describing our interconnectedness. In this case, however, the concept is made small enough to feel real, and practicing it only takes a few minutes each day.

At its core, wise speech is about practicing this vow from Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh:

“Aware of the suffering caused by unmindful speech and the inability to listen to others, I vow to cultivate loving speech and deep listening….”

Rothberg shared many insights and practical strategies, including the Four Guidelines for Wise Speech, which have since become a habit (as well as sticky notes posted on the wall above my work computer). They are as follows:

1. Truthfulness

2. Helpfulness

3. Kindness

4. Clear Intention (including good timing, appropriateness, non-distractedness)

The key here is more about consistent practice than discovering your take on the word-level meanings (although that is important).

Many of my work calls take place via computer-to-computer video conversations. Right before each call, I take a few deep breaths and then spend 10-20 seconds internalizing each guideline.

As seemingly insignificant as that sounds, this time allows me to check-in with how I’m feeling—a critical first step to ensuring that my inner suffering (such as unrelated negativity or frustration, for example) doesn’t manifest in some form that causes suffering for the recipient. Wise speech is all about entering into conversations with our best and most authentic intention—which demands feeling our feelings, not faking kindness.

Herein lies part of the ripple effect: I didn’t realize how good the practice of wise speech would make me feel as it’s happening. Before developing this practice, I thought wise speech was mostly a way to improve the life of the recipient.

The ripple continues from there, as my now outwardly projected inner sense of awareness and well-being is absorbed by the recipient who then (as I’ve been told now on several occasions) extends that energy into their next interaction.

It’s a glimpse into what Thich Nhat Hanh refers to as interbeing, a concept describing our interconnectedness. In this case, however, the concept is made small enough to feel real, and practicing it only takes a few minutes each day.

Published on January 20, 2020 11:50

•

Tags:

communication, mindfulness, wise-speech

Slowing down to wake up

The core of my online poetry class, now 3,500+ students strong, is the concept of slowing down to wake up.

It has applications just about everywhere. Consider how it works when we approach that red light we always seem to get. When we slow down and come back to our breath, we can see there’s a far better use of our finite energy on this earth than burning it in the frustration we typically feel in this moment. That’s waking up.

The practice remains, I believe, an untapped resource for writers, which is why I built an entire class around it.

The most powerful entertainment and technology giants would prefer we keep going fast and remain asleep as we consume their content. The more going fast becomes a habit for us, the more profitable it is for them. As such, I see slowing down to wake up both as a radical act of defiance and as a radical act of self-compassion.

It has applications just about everywhere. Consider how it works when we approach that red light we always seem to get. When we slow down and come back to our breath, we can see there’s a far better use of our finite energy on this earth than burning it in the frustration we typically feel in this moment. That’s waking up.

The practice remains, I believe, an untapped resource for writers, which is why I built an entire class around it.

The most powerful entertainment and technology giants would prefer we keep going fast and remain asleep as we consume their content. The more going fast becomes a habit for us, the more profitable it is for them. As such, I see slowing down to wake up both as a radical act of defiance and as a radical act of self-compassion.

Published on January 23, 2020 09:46

•

Tags:

mindfulness, self-compassion

DMAIC for your mind

I’ve been reading about Six Sigma lately. It’s a set of techniques and tools for optimizing process performance and attaining perfection — defined in this case as no more than 3.4 defects per million opportunities.

Think of it as a process for improving process. It’s underpinned by an improvement cycle referred to as DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control). Here’s a glimpse into how it looks:

The more I read, the more I wonder about DMAIC’s application for improving our habits of thought, the thinking processes we may want to improve.

While contemplative and therapeutic practices are the foundation in this regard, might there be room to embed within those a cycle similar to DMAIC?

So few of us get to the Define stage, where we’ve mapped out which parts of our thinking we want to improve. Maybe it’s a recurring negative thought or a recurring thought that adds no value to our life but takes up a significant amount of our mental energy.

From there, we could move to Measure. This is where a practice like meditation would be critical as it allows us to watch our thoughts coming in like waves. During a 20-minute meditation, for example, we could measure the times this thought enters our thought-stream.

The next step, Analyze, would be about getting to the root cause. Why does this thought capture so much of our attention? This is where working with a trained therapist could be incredibly beneficial. And their influence would be important as well for the Improve phase. Once we’ve discovered the cause, how can we form new mental habits?

Control, then, would be about continuing the practice and working to discover other ways of thinking we’d like to improve.

The idea needs to be fleshed out more (for example, I don’t think it’d be a healthy thing to refer to our natural habits of thought as “defects”), but it seems there could be some potential for those wanting to improve and optimize their inner worlds.

Think of it as a process for improving process. It’s underpinned by an improvement cycle referred to as DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control). Here’s a glimpse into how it looks:

The more I read, the more I wonder about DMAIC’s application for improving our habits of thought, the thinking processes we may want to improve.

While contemplative and therapeutic practices are the foundation in this regard, might there be room to embed within those a cycle similar to DMAIC?

So few of us get to the Define stage, where we’ve mapped out which parts of our thinking we want to improve. Maybe it’s a recurring negative thought or a recurring thought that adds no value to our life but takes up a significant amount of our mental energy.

From there, we could move to Measure. This is where a practice like meditation would be critical as it allows us to watch our thoughts coming in like waves. During a 20-minute meditation, for example, we could measure the times this thought enters our thought-stream.

The next step, Analyze, would be about getting to the root cause. Why does this thought capture so much of our attention? This is where working with a trained therapist could be incredibly beneficial. And their influence would be important as well for the Improve phase. Once we’ve discovered the cause, how can we form new mental habits?

Control, then, would be about continuing the practice and working to discover other ways of thinking we’d like to improve.

The idea needs to be fleshed out more (for example, I don’t think it’d be a healthy thing to refer to our natural habits of thought as “defects”), but it seems there could be some potential for those wanting to improve and optimize their inner worlds.

Published on January 29, 2020 09:49

•

Tags:

mindfulness, six-sigma, thinking

3 common barriers to the examined life

Socrates is often credited with saying, "The unexamined life is not worth living."

While many of us strive to live by this quote, there isn't much out there about the barriers that prevent us from examining our lives (let alone strategies for how to help us break through these barriers).

Here are 3 common barriers, plus some insight based on what's worked for me:

1. Dogma. It fills up more of our thinking than most of us would like to admit. Whether it's a Bible verse or a mantra from Tony Robbins, it's important to see these as gateways to inner work—not as the inner work itself. Dogma, at its best, serves as a gateway. At its worst, it serves as a crutch. The examined life examines crutches and uses them strategically, not as defaults.

2. Lack of privilege. It takes a certain degree of privilege to have the space necessary to observe how we live. If you're reading this post on Goodreads there's a good chance you have enough to get started.

3. Negativity bias / self-judgement. While examining, it's critical to be aware of and work to break free from negative energies so you can view your life objectively. The alternative is getting stuck in thought patterns that propel you towards questioning and criticizing yourself rather than discovering opportunities for growth. There is a fine line here, and it continues to demand a lot of my energy to remain on the positive side.

While many of us strive to live by this quote, there isn't much out there about the barriers that prevent us from examining our lives (let alone strategies for how to help us break through these barriers).

Here are 3 common barriers, plus some insight based on what's worked for me:

1. Dogma. It fills up more of our thinking than most of us would like to admit. Whether it's a Bible verse or a mantra from Tony Robbins, it's important to see these as gateways to inner work—not as the inner work itself. Dogma, at its best, serves as a gateway. At its worst, it serves as a crutch. The examined life examines crutches and uses them strategically, not as defaults.

2. Lack of privilege. It takes a certain degree of privilege to have the space necessary to observe how we live. If you're reading this post on Goodreads there's a good chance you have enough to get started.

3. Negativity bias / self-judgement. While examining, it's critical to be aware of and work to break free from negative energies so you can view your life objectively. The alternative is getting stuck in thought patterns that propel you towards questioning and criticizing yourself rather than discovering opportunities for growth. There is a fine line here, and it continues to demand a lot of my energy to remain on the positive side.

Published on January 30, 2020 18:59

•

Tags:

mindfulness, reflection