David W. Tollen's Blog, page 3

January 16, 2020

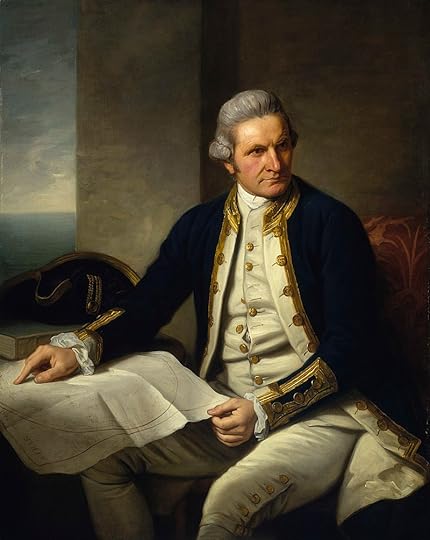

This week in history: Captain Cook

This week in history, the United Kingdom’s Captain James Cook celebrated two accomplishments. In 1773, he led the first known expedition to sail south of the Antarctic Circle. Cook and his crew were trying to find an imagined continent called Terra Australis – or to prove that it didn’t exist. Scholars had long believed the Earth must be “balanced,” with the same amount of land in the northern and southern hemispheres. The south had too little, so there had to be a missing continent. But Cook sailed to every predicted location of Terra Australis (“southern land”) and found nothing but open water, more or less disproving the theory. (Cook did not find Antarctica, though he suspected its existence. But this actual southern continent was too small to support the Terra Australis “hemisphere balance” theory.)

Cook’s second achievement this week came in 1778. He and his crew became the first known Europeans to visit the Hawaiian Islands. He called them the “Sandwich Islands,” after the Earl of Sandwich, but fortunately the name didn’t stick. Sadly, Hawaii was Cook’s last port of call. The Hawaiians were friendly during the initial British visit. But relations soured on a second visit in 1779, leading to violence and deaths on both sides, eventually including the captain himself.

The post This week in history: Captain Cook appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

January 10, 2020

This week in history: Louis Braille

Bronze bust of Louis Braille, created by Frédéric-Étienne Leroux (1887)

This week in 1809, Louis Braille was born in a small French town called Coupvray. He’s known for creating the braille reading and writing system for the visually impaired. Louis lost his eyesight at age 5. At age 10, he enrolled in one of the first schools for blind children. The school used the “Haüy system” for reading, named after its inventor, the school’s founder. Books were simply printed with raised letters the reader could feel. But the Haüy books were very heavy, and the students had a hard time reading them. Braille wanted something better. In 1821 he stumbled across a military communication system designed for silent night reading. It used raised dots and dashes on thick paper. This “night writing” was too complex, but it inspired Braille. By 1824, at just 15 years old, he had created his own, far better system.

Braille eventually became a professor at his childhood alma mater, but the faculty didn’t adopt his system during his lifetime. They liked the cumbersome Haüy system. Eventually, the students themselves insisted on braille, and the school adopted it two years after its inventor’s death. Today, braille is the world’s primary reading system for the visually impaired.

The post This week in history: Louis Braille appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

January 3, 2020

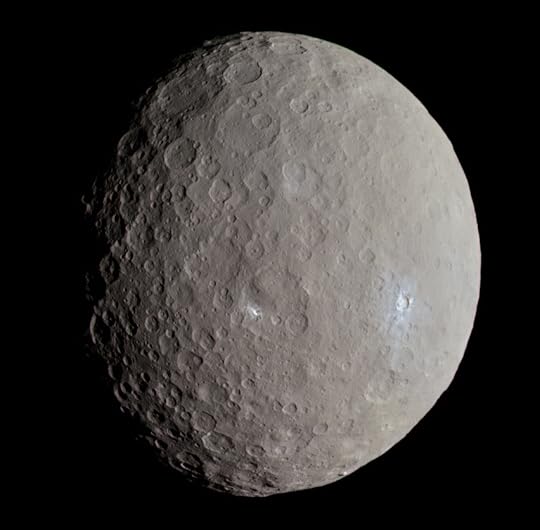

This week in history: Ceres

Ceres

This week in 1801, astronomer-priest Giuseppe Piazzi discovered a new astronomical body between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. He named it Ceres Ferdinandea. Ceres was the ancient Roman goddess of agriculture and motherhood – the Latin version of the Greeks’ Demeter, mother of Hades’ wife Persephone. So in choosing Ceres, Piazzi followed tradition: naming astronomical bodies after Roman gods (e.g., Venus, Jupiter, Saturn). In choosing Ferdinandea, however, Piazzi departed from tradition. The name honored Ferdinand III, king of Piazzi’s homeland, Sicily – who was also Ferdinand IV of Naples. The astronomers of other nations declined to honor King Ferdinand, so only the name Ceres stuck. Piazzi originally reported Ceres as a comet, but he suspected it was a planet, and other astronomers soon agreed. By the 1850’s, however, star-watchers had discovered many other small astronomical bodies orbiting between Jupiter and Mars, and they coined a new terms for the whole group: asteroids. Ceres has been considered an asteroid ever since. But Ceres stands out from its crowd, since it’s the biggest asteroid and the only one to be rounded (globe-shaped), due to its own gravity. As a result, Ceres’ status changed again in 2006, when astronomers demoted Pluto from planet status and created a new category: dwarf planet. Dwarf planets are globe-shaped bodies that don’t orbit a planet – they’re not moons – but that have not cleared their orbit of other objects, the way full planets do. Pluto’s demotion outraged many astronomy fans, but Ceres had been promoted. Today, it’s the only object classified as both an asteroid and a dwarf planet.

Photo by Justin Cowart, used with permission under CC BY 2.0

The post This week in history: Ceres appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

December 23, 2019

This week in history: Hagia Sophia

Photo by Arild Vagen, used with permission under CC BY-SA 3.0

This week in 537, eastern Roman emperor Justinian I completed the Hagia Sophia: the great cathedral of his capital, Constantinople. Upon completion and for centuries thereafter, it was the largest building in the world. Justinian’s realm was the eastern half of the original Roman Empire, and the Hagia Sophia became the central cathedral of the Eastern half of the Roman Christian church, seat of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Eventually, the two great sections of the church broke into the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, led by the Patriarch of Rome – a.k.a. the Pope. The Hagia Sophia remained the central cathedral of the Eastern church until 1453, when Constantinople fell to Muslim invaders and became the capital of the Turks’ Ottoman Empire. The conquerors converted the cathedral into a mosque and added its now-iconic minarets: the slender towers you see on many mosques, used for the call to prayer. In the 1930’s, however, the new, secular state of Turkey closed the mosque and transformed it into the Ayasofya Muzesi, or the Museum of the Hagia Sophia. You can visit the museum to this day, in Istanbul, the Turkish name for Constantinople.

The post This week in history: Hagia Sophia appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

December 17, 2019

This week in history: The Boston Tea Party

“Americans throwing the cargoes of the Tea Ships into the River at Boston” from

The History of North America by W.D. Cooper published in 1789

This week in 1773, the Sons of Liberty disguised themselves as Native Americans, boarded British ships in Boston Harbor, and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water. The Boston Tea Party escalated the colonists’ struggle against the Tea Act, which the British Parliament had passed in May, imposing a tax on tea. The colonists had long enjoyed a period of “benevolent neglect”—low taxes and little interference from their government in London—but those days had recently come to an end. Parliament needed money and looked to its American colonies for a contribution. To the colonists, this was “no taxation without representation,” since the colonies had no Members of Parliament and so no vote or voice. To the British, the taxes were more than fair, since the colonists had long enjoyed the benefits of the British Empire, including military protection from the French and Native Americans, without shouldering the cost. Neither side ever budged, so we now remember the Boston Tea Party as a key step toward rebellion and the American War for Independence.

The post This week in history: The Boston Tea Party appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

December 12, 2019

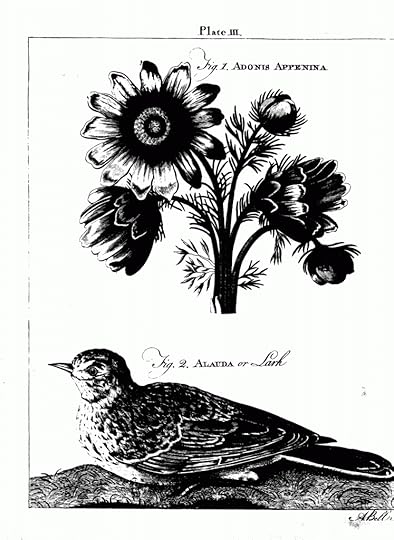

This week in history: Encyclopaedia Britannica

This week in 1768, Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell of Scotland published the first edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. It had just 3 volumes—quite a contrast to the thirty-two volumes of the fifteenth and final edition, published in 2010. Despite small beginnings, Britannica quickly gained a reputation for excellence and was soon considered the most authoritative English language encyclopedia. Ironically given the name, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. has become an American company. Sears Roebuck bought the rights in 1920, and the company now operates out of Chicago.

Sadly, the information economy offers little market for large collections of large books, so the 2010 edition was the last hard copy. But the company now publishes Encyclopædia Britannica Online. It’s going strong, though it faces fierce competition from free online encyclopedias like Wikipedia – which benefits from a staff of 7.7 billion potential writers, since it’s open source – and Ancient History Encyclopedia.

This image is a copperplate from the first edition, engraved by Andrew Bell.

The post This week in history: Encyclopaedia Britannica appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

December 3, 2019

This week in history: Napoleon III

This week in 1852, Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte became Emperor of France. His father was the younger brother of the original Napoleon. And his mother was the daughter of the famous Josephine – the long-term mistress and eventually wife of the first Napoleon — by her other (first) husband. To capitalize on his famous uncle’s reputation, the new emperor took the name Napoleon III. (In theory, the first Napoleon’s four-year-old son had ruled for about two weeks in 1815, as Napoleon II.)

Napoleon III had been elected President of France in 1848, but by 1852, he had termed out and so couldn’t be reelected. So proclaiming the Second French Empire was his alternative to retiring.

The emperor actually supported popular sovereignty around Europe, as well as national self-determination – like the original Napoleon. He also modernized the French economy. He stimulated the stock marketing, vastly increased France’s railway network, built roads and canals, and invested in education. Napoleon III also increased French power – but not enough. A giant was rising to the east, as Prussia worked to unite the German principalities into a single country. The Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, and the emperor promptly lost to the forces of the Prussian king and his mighty chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. Napoleon III was captured and dethroned, leading to the establishment of the French Third Republic – as well as the German Empire (with the former Prussian king as its first Kaiser, or Emperor). Napoleon III died in exile in 1873.

The post This week in history: Napoleon III appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

November 26, 2019

This week in history: Thespis

Photo by Sailko, used with permission under Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5)

This week in 534 BCE, Thespis of Icaria became the first person we know of to portray a character on stage in ancient Greece. He sang about myths to an audience in Athens. But rather than just narrating by song, he played the various characters in the story, using masks to differentiate them. Thespis also won Athens’ first recorded “Best Tragedy” competition. Then he took it on the road, performing in the various Greek city-states with his masks, props, and costumes. Thespis changed theatrical story-telling in the ancient world – and today, we use “thespian” as a synonym for actor, in his honor.

The post This week in history: Thespis appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

November 18, 2019

This week in history: Queen Elizabeth I

This week in 1558, Elizabeth Tudor was declared queen of England and Ireland, following the untimely death of her half-sister, Queen Mary. Elizabeth was the daughter of King Henry VIII by his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Her first and most important job as queen was to marry and produce an heir. Her sister Mary had married the King of Spain (leading to an unhappy long-distance marriage), and Elizabeth could have chosen a foreign royal too. Many of her advisors, on the other hand, preferred a noble English husband. Either way, conventional wisdom demanded marriage, since a kingdom without an heir is unstable, and since a mere woman can’t reign alone. Yet after Elizabeth had flirted with various foreign and English suitors for years, it became clear the queen would never marry. It’s not that Elizabeth disliked men. In fact, she apparently had a taste for big, athletic bad boys. Rather, the queen probably felt that, in a man’s world, a husband would steal some of her authority. And for an energetic, forceful, and smart ruler like Queen Elizabeth, that was unacceptable. So she reigned alone and became known and loved as the Virgin Queen (though her actual virginity seems doubtful). And she ruled well, blazing her own trail as a ruling queen without husband or heir. Her forty-five-year reign saw a steady rise in English might and witnessed the defeat of Europe’s greatest power – as Elizabeth’s navy (and bad weather) foiled a Spanish invasion and destroyed the Spanish Armada, in 1588. The Elizabethan era also saw a great flowering of English culture, including the rise of English drama and the start of Shakespeare’s career.

The queen’s refusal to marry, however, was not without consequences. She did not need a man to help her rule, but she did need an heir. Controversy about succession swirled around her later years. She ultimately let it be known that the king of Scotland would succeed her. King James was the son of Queen Elizabeth’s cousin and defeated rival, Mary Queen of Scots. So he descended from Henry VII, Elizabeth’s grandfather and the founder of the Tudor dynasty. Queen Elizabeth never did officially name James her heir, but when she finally died in 1603, King James took the throne, and the union of England, Ireland, and Scotland began.

The post This week in history: Queen Elizabeth I appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

This week in history: Queen Elizabeth

This week in 1558, Elizabeth Tudor was declared queen of England and Ireland, following the untimely death of her half-sister, Queen Mary. Elizabeth was the daughter of King Henry VIII by his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Her first and most important job as queen was to marry and produce an heir. Her sister Mary had married the King of Spain (leading to an unhappy long-distance marriage), and Elizabeth could have chosen a foreign royal too. Many of her advisors, on the other hand, preferred a noble English husband. Either way, conventional wisdom demanded marriage, since a kingdom without an heir is unstable, and since a mere woman can’t reign alone. Yet after Elizabeth had flirted with various foreign and English suitors for years, it became clear the queen would never marry. It’s not that Elizabeth disliked men. In fact, she apparently had a taste for big, athletic bad boys. But the queen apparently felt that, in a man’s world, a husband would steal some of her authority. And for an energetic, forceful, and smart ruler like Queen Elizabeth, that was unacceptable. So she reigned alone and became known and loved as the Virgin Queen (though her actual virginity seems doubtful). And she ruled well, blazing her own trail as a ruling queen without husband or heir. Her forty-five-year reign saw a steady rise in English might and witnessed the defeat of what was then Europe’s greatest power – as Elizabeth’s navy (and bad weather) foiled a Spanish invasion and destroyed the Spanish Armada, in 1588. The Elizabethan era also saw a great flowering of English culture, including the rise of English drama and the start of Shakespeare’s career.

The queen’s refusal to marry, however, was not without consequences. She did not need a man to help her rule, but she did need an heir. Controversy about succession swirled around her later years. She ultimately let it be known that the king of Scotland would succeed her. King James was the son of Queen Elizabeth’s cousin and defeated rival, Mary Queen of Scots. So he descended from Henry VII, Elizabeth’s grandfather and the founder of the Tudor dynasty. Queen Elizabeth never did officially name James her heir, but when she finally died in 1603, King James took the throne, and the union of England, Ireland, and Scotland began.

The post This week in history: Queen Elizabeth appeared first on DavidTollen.com.