David W. Tollen's Blog, page 2

April 9, 2020

Follow-up to REAL theories for the origin of April Fool’s Day

Last week, I posted this article that had 3 real theories on the origins of April Fool’s Day, and 3 fake theories. Below are the 3 true theories:

1. In 1582, France switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, which moved New Year’s Day from March to January. People who still celebrated in March were mocked as fools.

3. Ancient Romans celebrated Hilaria on the vernal equinox, in late March, to honor mother goddess Cybele. The ritual included dressing up in disguises.

5. Mother Nature often “fooled” ancient and medieval people in the northern hemisphere around the time of the vernal equinox, in late March, through shifting weather patterns that rarely seemed to match the season.

These I made up (mixing truth and fiction).

2. In 1319, authorities in Dresden and the surrounding German towns executed nearly 700 Jews and lepers, after a teenage boy claimed the two groups had plotted to poison the wells. On April 6 of 1322, the boy admitted that he had fabricated the claim. [The truth: this sort of accusation against lepers and particularly Jews was common during the middle ages, particularly in response to plague. But the whole Dresden story and the connection to April Fool’s is made up.]4. The pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons worshipped a trickster god named Lôgna – their version of the Norse god Loki – and they celebrated his holiday in early April. [The Anglo-Saxons did worship Lôgna, and he was their version of Loki. But the rest is made up.]6. During the 1490’s, a Dutch tradesman named Willem Cruyff claimed to be the true duke of Burgundy and attracted a following with promises of tax relief. Authorities executed him on March 31 or April 1 of 1497, along with six of the “fools” who followed him. [Fake monarchs cropped up here and there in European history, and they sometimes led rebel movements—like the fake Peter III in Russia. But the whole Willem Cruyff story is made up, as is his name.]

How did you do? Were you able to figure out which were fact and which were fiction?

The post Follow-up to REAL theories for the origin of April Fool’s Day appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

April 1, 2020

Which of these are REAL theories for the origin of April Fool’s Day?

Historians debate the origins of April Fool’s Day, with three possible explanations. Which of the following are real; which three are actual theories for the holiday’s origin?

In 1582, France switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, which moved New Year’s Day from March to January. People who still celebrated in March were mocked as fools.

In 1319, authorities in Dresden and the surrounding German towns executed nearly 700 Jews and lepers, after a teenage boy claimed the two groups had plotted to poison the wells. On April 6 of 1322, the boy admitted that he had fabricated the claim.

Ancient Romans celebrated Hilaria on the vernal equinox, in late March, to honor mother goddess Cybele. The ritual included dressing up in disguises.

The pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons worshipped a trickster god named Lôgna – their version of the Norse god Loki – and they celebrated his holiday in early April.

Mother Nature often “fooled” ancient and medieval people in the northern hemisphere around the time of the vernal equinox, in late March, through shifting weather patterns that rarely seemed to match the season.

During the 1490’s, a Dutch tradesman named Willem Cruyff claimed to be the true duke of Burgundy and attracted a following with promises of tax relief. Authorities executed him on March 31 or April 1 of 1497, along with six of the “fools” who followed him.

Check back next week, on April 8, for the correct answers!

(Using search engines would be cheating!)

The post Which of these are REAL theories for the origin of April Fool’s Day? appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

March 20, 2020

This week in history: Uncle Tom’s Cabin

This week in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe published her anti-slavery novel, UNCLE TOM’S CABIN. Beecher Stowe was a teacher at Hartford Female Seminary in Connecticut. She originally published her most famous work as a 40-week serial in “The National Era,” an abolitionist periodical. Publisher John Jewett saw potential and proposed that Stowe turn the serial story into a book. He had good reason. The story was so popular that, if the magazine ever published without a new chapter, it received multiple protest letters. So Beecher Stowe published. She sold 3,000 copies the first day, and UNCLE TOM’S CABINE soon sold out of its first print-run. The novel ultimately became the second best selling book in the United States for the entire of the 19th Century, just behind the Bible.

Many scholars believe UNCLE TOM’S CABIN laid the groundwork for the surge in abolitionist votes that triggered the American Civil War. The story revealed the cruelty and barbarity of slavery.

The post This week in history: Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

March 13, 2020

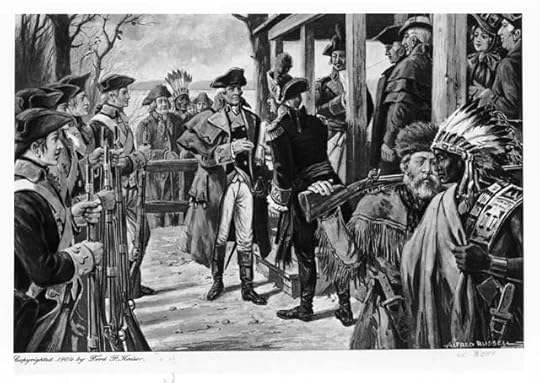

This week in history: Louisiana Purchase

This week in 1804, the Louisiana Territory transferred from French to U.S. sovereignty, with the change marked by a ceremony in St. Louis. The territory had actually changed hands before, from France to Spain and then, as late as 1800, back to France. France’s First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte (later emperor), had planned to reestablish a French colony in North America, but he found himself short of resources, thanks to troubles at home and war with Britain (and ultimately just about everyone else). Hard up for cash, Napoleon had sold the Louisiana Territory to the U.S.’s President Thomas Jefferson. The two republican leaders’ original plan just involved the purchase of New Orleans. But in 1803, French Treasury Minister Francois Barbe-Marbois had offered the whole, vast Louisiana Territory to the American negotiators, James Monroe (later President) and Robert Livingston. They jumped at it. In fact, President Jefferson exceeded his authority by committing to the purchase without Congress’ consent, but he could not pass up the chance to double America’s possessions.

The St. Louis ceremony this week in 1804 is called Three Flags Day. First, Spain formally transferred the territory back to France, symbolically completing the transaction agreed in 1800. The Spanish lowered their flag, and the French raised theirs – for 24 hours. Then, the French lowered their flag and America’s stars and stripes rose over the Louisiana Territory – presumably forever.

The post This week in history: Louisiana Purchase appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

March 5, 2020

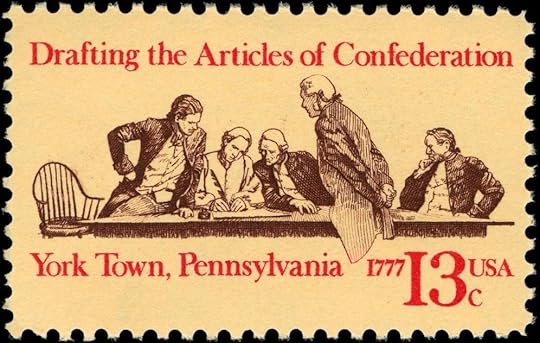

This week in history: the Articles of Confederation

This week in 1781, the Articles of Confederation went into effect in the United States, following ratification by the 13 colonies – a.k.a. states. Work on the Articles had begun in 1776, around the time of the Declaration of Independence. Completion took a year and a half, until November 5 of 1777 – for two reasons: uncertainty about what to include, as well as several moves from city to city, to avoid advancing British troops. In the end, the final draft included state sovereignty, en bloc voting by state in a unicameral Congress, and terms that left western land claims unresolved – up to individual states.

The Articles were submitted to the states in late November of 1777. Virginia was the first state to ratify, in December, while Maryland was the last, in 1781. During the years the states worked on ratifying the Articles, the U.S. government took them as the country’s de facto structure. When Congress received word on March 1, 1781 that Maryland had finally ratified the Articles, it announced them as the law of the land. The Articles of Confederation remained America’s governing law until 1789, when today’s Constitution was ratified.

Image is a 1977 commemorative stamp marking the bicentennial of the Articles of Confederation.

The post This week in history: the Articles of Confederation appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

February 21, 2020

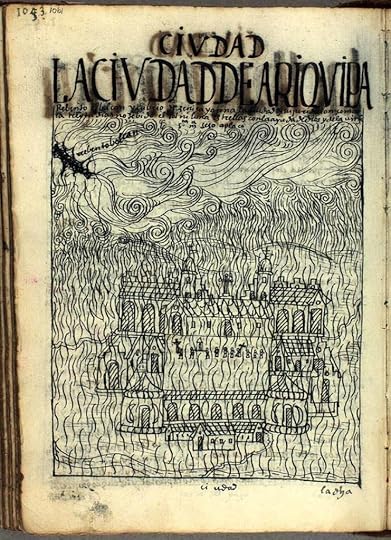

This week in history: Huaynaputina

This week in 1600, South America experienced the most violent volcanic eruption in its recorded history. The volcano known as Huaynaputina, in Peru, exploded, and the impact was global. The surrounding area was devastated, of course – much of it buried in six feet of volcanic ash and rock. But the eruption also altered global climate, as major volcanoes sometimes do – with ash and other particulates flung into the sky blocking sunlight around the world, leading to falling temperatures. That in turn brought famines, floods, droughts, and waves of cold weather to various regions in the northern hemisphere. In fact, the eruption of Huaynaputina and other volcanoes around the same time probably contributed to the Little Ice Age: a period of historic cold weather around the world, from the 1600’s to, arguably, the 1800’s.

The image above is an artist’s depiction of Arequipa, the city closest to Huaynaputina, showing ash falling on the city following the eruption.

The post This week in history: Huaynaputina appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

February 14, 2020

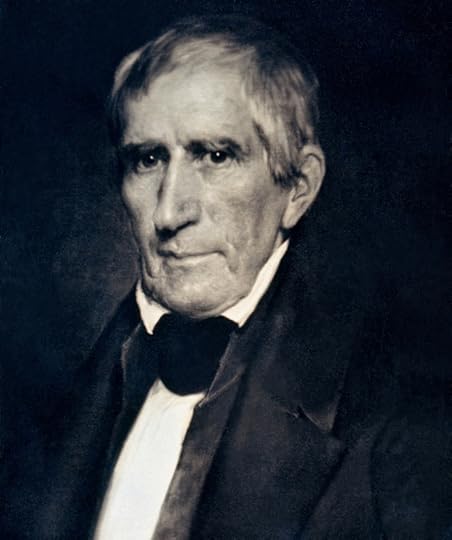

This week in history: William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison, America’s 9th President, was born this week in 1773. Harrison probably would not be pleased to learn his greatest legacy: establishing the system for presidential succession, by dying in office. The Constitution has surprisingly unclear terms about succession, so when Harrison died in 1841, no one knew if the Vice President would become President or just exercise some or all of the President’s powers. Harrison’s Vice President, John Tyler, brought order to confusion by claiming a constitutional mandate and taking the oath of office as President. Vice Presidents have seamlessly succeeded to the presidency ever since, whenever the chief dies in office.

Harrison was a successful general, best known for the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, where he defeated Tecumseh, the leader of a Native American tribal federation. The battle gave the future President a nickname, and during the 1840 election, his ticket’s campaign slogan was “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.” Harrison turned 68 shortly after winning the election, making him America’s oldest President until Ronald Reagan (140 years later). He died because he insisted on giving his extremely long inaugural speech – the longest in U.S. history – outside on a cold and rainy day. He contracted pneumonia soon after the inauguration and died 31 days later.

The post This week in history: William Henry Harrison appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

February 5, 2020

This week in history: Groundhog Day

This past Sunday, the U.S. and Canada celebrated Groundhog Day (along with the Super Bowl). According to legend, if a groundhog sees its shadow on February 2nd, after emerging from its burrow, winter will continue for six more weeks. If the groundhog sees no shadow, spring will arrive early. So Groundhog Day involves a reversal of assumptions: clear weather on 2/ 2 means more winter, since clear skies lead to shadows, while cloudy weather means an early spring.

Groundhog Day owes its origins to Candlemas Day, a German festival celebrated on February 2nd. German folklore said winter would drag on if Candlemas Day was clear and sunny, but spring could come early if not. The tradition took that idea a step further by assigning various animals the role of weather-checker. If a bear saw its shadow on Candlemas – or a fox, badger, or hedgehog – the weather must be clear and winter would continue. German immigrants brought the tradition to Pennsylvania during the 1700s. These were the Pennsylvania Dutch, and their name is an anglicization of “Deutsch,” the German word for German. The Pennsylvania Dutch found hedgehogs in short supply in Pennsylvania, so they swapped out their traditional weather-checkers for the more abundant groundhog. The traditional spread across North American during the mid-1800s.

Bill Murray’s movie, Groundhog Day, features a beast named Punxsutawney Phil. He’s a real animal (said to be immortal), living in Punxsutawney, Pa, which celebrates Groundhog Day every year, with Phil making his appearance at a spot called Gobbler’s Knob.

Photo originally by April King & cropped for this blog post, used with permission under CC BY-SA 3.0

The post This week in history: Groundhog Day appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

January 31, 2020

This week in history: the Diet of Worms

This week in 1521 saw the opening of the Diet of Worms: the great meeting of the princes of the Holy Roman Empire to address the turmoil created by Martin Luther. Luther was a clergyman and professor who had repeatedly criticized the Church and attacked its doctrines. His aggressive and outspoken writings had found sympathetic ears across Germany and the rest of the empire, striking fear in the Catholic establishment. Emperor Charles V presided over the Diet, in the city of Worms in the German Rhineland, and he summoned Luther to answer for his views. Luther naturally feared that attending the Diet would lead to his death, but his patron and protector, Elector Frederick III of Saxony, negotiated safe passage to and from the meeting. The princes, who included many of Germany’s great bishops, demanded that Luther renounce his attacks on the Church. Luther refused, so the Diet condemned him. On May 25, the emperor issued the Edict of Worms: “[W]e forbid anyone from this time forward to dare, either by words or by deeds, to receive, defend, sustain, or favor the said Martin Luther. On the contrary, we want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic, as he deserves, to be brought personally before us …, whereupon we will order the appropriate manner of proceeding against the said Luther. Those who will help in his capture will be rewarded generously for their good work.” Worse for Luther, his opponents privately agreed to breach the safe conduct and arrest him as he left Worms. But Elector Frederick rescued his client, staging a pretended attack on Luther on the road, “abducting” him, and spirting him away to the safety of Wartburg Castle. There, Luther lived on under the Elector’s protection and continued his written attack on the Catholic Church. His influence soared, launching Protestant movement across Europe.

Luther at the Diet of Worms, painting by Anton von Werner (1877)

The post This week in history: the Diet of Worms appeared first on DavidTollen.com.

January 25, 2020

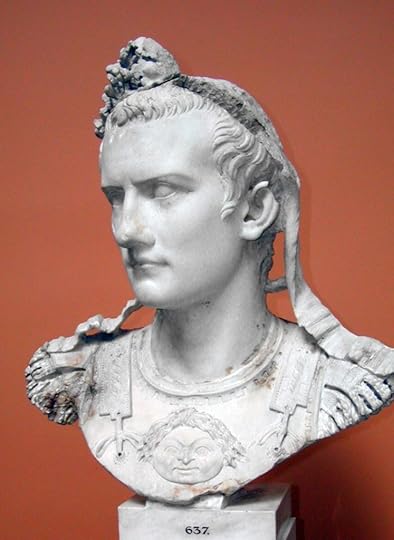

This week in history: Caligula

This week in 41 CE, a faction Roman leaders assassinated their emperor, Caligula. The emperor had oppressed the nobles and the Senate (though not necessarily the common people), so this was not the first plot against his rule. The trigger for this final and successful conspiracy isn’t entirely clear, but Caligula had recently announced plans to move his seat of power from Rome to Alexandria, in Egypt. That would have robbed the Roman elite of much of their power. Another theory suggests Caligula was just too dangerous, since he was mentally imbalanced and possibly insane. His enemies claimed Caligula considered himself a god – and not just holy and exalted, like the two Roman emperors before him, but actually a living deity, on par with Jupiter and Minerva. They also say he slept with his sisters, as gods do, made his horse a senator, declared war on Neptune, and worst of all, executed high-ranking Romans on a whim. Whatever the cause, a faction of the imperial Praetorian Guard and some senators attacked Caligula as he addressed a troupe of actors near his palace. Caligula’s more loyal German guard – foreigners from the wild lands of the north – arrived quickly to rescue the emperor, but too late: the conspirators had stabbed him 30 times. The conspirators also killed Caligula’s wife and young daughter, no doubt to avoid repercussions, but they did not catch the emperor’s old uncle, the lame, stammering scholar Claudius. Loyal member of the Praetorian Guard escorted Claudius to safety and soon proclaimed him emperor. So it fell to Claudius to execute the conspirators and restore order, and possibly sanity, to the Roman Empire.

Bust of Caligula image by Louis le Grand, used with permission under CC BY-SA 3.0

The post This week in history: Caligula appeared first on DavidTollen.com.