Terri Windling's Blog, page 80

January 26, 2018

Quote of the Day

"The most important thing is to hold on, hold out, for your creative life, for your solitude, for your time to be and do, for your very life." - Clarissa Pinkola Est��s

The photograph is of Andrew Wyeth's studio.

Wild prayer

After weeks of rain storms, yesterday there was blue sky and a rainbow over our village. In a long, dark season of water-soaked fields and foot trails ankle-deep in mud, it felt a blessing.

Today, it is clear over Meldon Hill, though a bank of dark clouds hovers over the moor. Sun or rain, I am ready for both. Rainbow-blessed and vision restored, I'm reminded to love the earth's full palette: the delicacy of winter blue, the wet vibrancy of green and gold, but also the spectrum of color that gives us grey days, comfortless as they sometimes seem. Grey is the color of mist, mystery, mythic entrances to the Otherworld. Grey is the hidden and the unseen -- which we sometimes need to be ourselves.

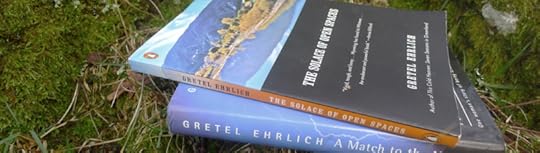

In her essay collection Wild Comfort, Kathleen Dean Moore takes sorrow and the hardships of life into nature, seeking clarity, solace, and a form of prayer unattached to the religion she was raised in and no longer practices. Alone in her kayak on a small mountain lake, she is enclosed in the grey world of falling snow, cut off from sight of the land by the storm. In the thick of the snow squall, she writes:

"a frog began to sing. It must have been a tree frog, Hyla regilla. Of course I couldn't see it; I couldn't see anything but snow beyond my vanished bow. But I knew that song, and I could imagine the tiny frog up to its eyes in water, snowflaked falling on its head fiery green enough to melt the snow.

"As long as the frog sings, I will not be lost in the squall. The song tells me where the cattails are, and the cattails mark the shore. I am sure of this much, that Earth lights these small signal fires -- not for us, but among us -- and we can find them if we look. If we are not afraid, if we keep our balance, if we let our anxious selves dissolve into the beauties and mysteries of the night, we will find a way to peace and assurance. Signal fires burn all over the land."

Here is the prayer Moore finds in the middle of the storm, and that she offers to us:

"May the light that reflects on this water be a wild prayer. May water lift us with its unexpected strength. May we find comfort in the 'repeated strains of nature,' the softly sheeting snow, the changing seasons, the return of blackbirds to the marsh. May we find strength in light that pours under the snow and laughter that breaks through the tears. May we go out into the light-filled snow, among meadows in bloom, with a gratitude for life that is deep and alive. May Earth's fires burn in our hearts, and may we know ourselves to be part of this flame -- one thing, never alone, never weary of life."

May it be so. Mitakuye Oyasin.

The two passages quoted above are from Kathleen Dean Moore's essay "Never Alone or Weary" in Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature (Trumpeter Books, 2010); the poem in the picture captions is from The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov (New Directions, 2013); all rights reserved by the authors. I wrote about rainbows in my own personal symbology here, back in 2010.

January 25, 2018

Ursula Le Guin on the truth of fantasy

Like just about everyone else in the Mythic Arts field, I've been rocked by the death of Ursula Le Guin -- not only one of the greatest writers of our age, but also a vital, necessary figure for my generation of fantasy writers, editors, and illustrators. We entered the field in the late '70s and '80s when women were few and still unwelcome by a daunting number of professional colleagues, readers, and reviewers. Ursula was a guiding light, encouraging some of us directly, and many more through the pages of her books. In honor of her influential presence in American Arts & Letters for half a century (her first novel was published in 1966), I've gathered together all of the posts from the Myth & Moor archives related to her work. You'll find them here. The following post first appeared on Myth & Moor two years ago:

From The Language of the Night by Ursula K. Le Guin:

"I believe that maturity is not an outgrowing but a growing up: than an adult is not a dead child, but a child who has survived. I believe that all the best faculties of a mature human being exist in the child, and that if these faculties are encouraged in youth they will act wisely and well in the adult, but if they are repressed and denied in the child they will stunt and cripple the adult personality. And finally, I believe that one of most deeply human, and humane, of these faculties is the power of imagination: so that it is our pleasant duty, as librarians, or teachers, or parents, or writers, or simply as grownups, to encourage that faculty of imagination in our children, to encourage it to grow freely, to flourish like the green bay tree, by giving it the best, absolutely the the best and purest, nourishment that it can absorb. And never, under any circumstances, to squelch it, or sneer at it, or imply that it is childish, or unmanly, or untrue.

"I believe that maturity is not an outgrowing but a growing up: than an adult is not a dead child, but a child who has survived. I believe that all the best faculties of a mature human being exist in the child, and that if these faculties are encouraged in youth they will act wisely and well in the adult, but if they are repressed and denied in the child they will stunt and cripple the adult personality. And finally, I believe that one of most deeply human, and humane, of these faculties is the power of imagination: so that it is our pleasant duty, as librarians, or teachers, or parents, or writers, or simply as grownups, to encourage that faculty of imagination in our children, to encourage it to grow freely, to flourish like the green bay tree, by giving it the best, absolutely the the best and purest, nourishment that it can absorb. And never, under any circumstances, to squelch it, or sneer at it, or imply that it is childish, or unmanly, or untrue.

"For fantasy is true, of course. It isn't factual, but it's true. Children know that. Adults know it too and that's precisely why many of them are afraid of fantasy. They know that its truth challenges, even threatens, all that is false, all that is phony, unnecessary, and trivial in the life they have let themselves be forced into living. They are afraid of dragons because they are afraid of freedom.

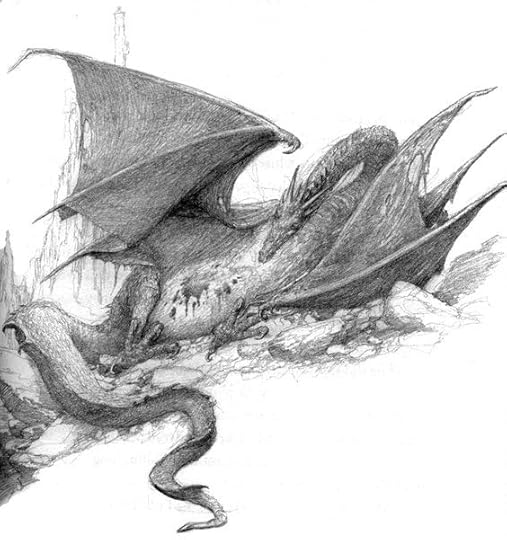

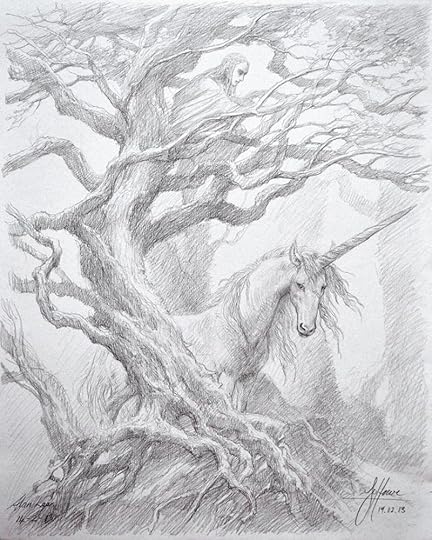

"So I believe that we should trust our children. Normal children do not confuse reality and fantasy -- they confuse them much less often than we adults do (as a certain great fantasist pointed out in a story called 'The Emperor's New Clothes'). Children know perfectly well that unicorns aren't real, but they also know that books about unicorns, if they are good books, are true books. All too often, that's more than Mummy and Daddy know; for, in denying their childhood, the adults have denied half their knowledge, and are left with the sad, sterile little fact: 'Unicorns aren't real.' And that fact is one that never got anyone anywhere (except in the story 'The Unicorn in the Garden,' by another great fantasist, in which it is shown that a devotion to the unreality of unicorns may get you straight into the loony bin.) It is by such statements as, 'Once upon a time there was a dragon,' or 'In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit' -- it is by such beautiful non-facts that we fantastic human beings may arrive, in our peculiar fashion, at truth."

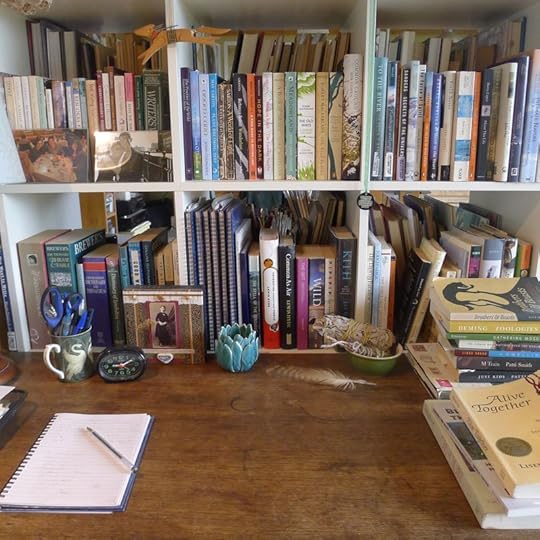

Words: The passage above is from "Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?" by Ursula K. Le Guin, which first appeared in PNLA Quarterly 38 (1974), and can also be found in her essay collection The Language of the Night (GP Putnams, 1979). Drawings: The two dragon drawings are by Alan Lee, and the unicorn drawing by Alan Lee & John Howe. Photographs: A quiet morning the studio. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artists.

Words: The passage above is from "Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?" by Ursula K. Le Guin, which first appeared in PNLA Quarterly 38 (1974), and can also be found in her essay collection The Language of the Night (GP Putnams, 1979). Drawings: The two dragon drawings are by Alan Lee, and the unicorn drawing by Alan Lee & John Howe. Photographs: A quiet morning the studio. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artists.

January 24, 2018

Breaking open

From Wild Comfort by Kathleen Dean Moore:

" 'There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature,' Rachel Carson wrote. 'The assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.'

"I have never felt this so strongly as I do now, waiting for the sun to warm my back. The bottom may drop out of my life, what I trusted may fall away completely, leaving me astonished and shaken. But still, sticky leaves emerge from bud scales that curl off the tree as the sun crosses the sky. Darkness pools and drains away, and the curve of the new moon points to the place where the sun will rise again. There is wild comfort in the cycles and the intersecting circles, the rotations and revolutions, the growing and ebbing of this beautiful and strangely trustworthy world.

"I settle back on the rock and drag my sleeping bag over my knees. Diffuse light silvers the water; I can just make out a dragonfly nymph that crawls toward the surface with no expectation of flight beyond maybe a tightness in the carapace across its back. No matter how hard it tries or doesn't, there will come a time when the dragonfly pumps the crinkles out of its wings, and there they will be, luminous as mica, threaded with lapis and gold.

"No measure of human grief can stop Earth in its tracks. Earth rolls into sunlight and rolls away again, continents glowing green and gold under the clouds. Trust this, and there will come a time when dogged, desperate trust in the world will break open into wonder. Wonder leads to gratitude. Gratitude into peace."

Where, or how, do you find wild comfort?

The passage above is from Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, essays by Kathleen Dean Moore (Trumpeter Books, 2010); all rights reserved by the author. The text is the picture captions is adapted from a post after winter storms in 2012.

January 23, 2018

On a dark day in Devon

"This far north, the changes from winter to spring and from summer to autumn are rapid," wrote Sharon Blackie in 2012, when she was living on a croft in Scotland's Outer Hebrides. "In spring, a sudden clatter of light announces that winter is over; then one day around the beginning of September you wake up to find that summer slipped away while you weren't paying attention. There is none of the drawn out descent that characterizes the long sleepy slide into autumn in more southerly places.

"And so now here we are, entering that Long Darkness....In places like this, at this time of year, there are no distractions from being. And so we are now becoming engaged in our own responses to this lengthening darkness, to the more vivid reality of simply being. The process reminds me of the work I used to do as a narrative therapist, using personal storytelling and mythmaking with people undergoing life crisis or transitions. That descent into the underworld which underpins our most compelling myths and fairy stories is a real phenomenon for everyone -- whether or not we choose to heed the 'call to adventure.' For me, such descents have always been a time of deep excitement mixed with a little apprehension at whatever I might be allowing to enter next into my life. Though now, of course, I'm describing a different kind of descent, a seasonal -- annual -- descent into another mode of being as the year closes in and headspace opens up."

"This Outer Hebridean darkness is one of the inextricable links between place, weather and seasons which play a major role in our imaginative lives. Because weather and seasons are the foundations of our sense of belonging to a place. Curiously, perhaps, weather is rarely mentioned in writing about the sense of place. And yet, it is weather that largely shapes a place and its landscape.

"The islands of the Outer Hebrides, for example, are as they are precisely because of centuries of wind and driving rain. The land is boggy, treeless, hard, pared to the bones -- and possessed of a vivid, uncluttered clarity precisely for that reason. It's always surprising that so many people who come to live in these islands begin to long for periods of hot dry wind-free sunshine and to complain bitterly about the weather, as though the weather could somehow be extracted and then you'd be left with a place that was so much more reasonable to live in. But hot dry sunshine isn't the Outer Hebrides, it's Provence or Tenerif...or so many other places, but not this place."

"Weather is what you walk in, along with landscape, when you walk in a place. It isn't something accidental that happens to you as you walk on the surface of the earth: it's intrinsic. Anthropologist Tim Ingold writes about this in his book, Being Alive:

" 'To inhabit the open is not, then, to be stranded on a closed surface but to be immersed in the incessant movements of wind and weather, in a zone wherein substances and medium are brought together in the constitution of beings that, by way of their activity, participate in stitching the textures of the land....Sea and land are engulfed in a wider sphere of forces and relations comprise the weather-world. To perceive and to act in the weather-world is to align one's own conduct to the celestial movements of sun, moon and stars, to the rhythmic alterations of night and day and the seasons, to rain and shine, sunlight and shade.' "

"All over the world," wrote Gretel Erhlich in Orion Magazine in 2004, "the life of rocks, ice, mountains, snow, oceans, islands, albatross, sooty gulls, whales, crabs, limpets, and guanaco once flowed up into the bodies of the people who lived in small hunting groups and villages, and out came killer-whale prayers, condor chants, crab feasts, and guanaco songs. Life went where there was food. Food occurred in places of great beauty, and the act of living directly fueled people���s movements, thoughts, and lives.

"Everything spoke. Everything made a sound -- birds, ghosts, animals, oceans, bogs, rocks, humans, trees, flowers, and rivers -- and when they passed each other a third sound occurred. That���s why weather, mountains, and each passing season were so noisy. Song and dance, sex and gratitude, were the season-sensitive ceremonies linking the human psyche to the larger, wild, weather-ridden world....

"When did we begin thinking that weather was something to be rescued from?"

The passage by Sharon Blackie is from the Editorial page in EarthLines Magazine, November 2012. The passage by Gretel Ehrlich is from "Chronicles of Ice" in Orion Magazine, November 2004. The poem in the picture captions is from The Wrong Music by Olive Fraser (Canongate, 1989). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates.

January 22, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, women's voices from America....

Above: "Little Lies" by I'm With Her, a trio comprised of bluegrass & folk musicans Sara Watkins, Sarah Jarosz, and Aoife O'Donovan. The song is from their much-anticipated first album as a trio, See You Around, which comes out next month.

Below: "��migr��" by Alela Diane, a singer/songwriter from Portland, Oregon. The song appears on her fifth album, Cusp, due out next month. The album, she says, is an exploration of motherhood in many different guises, inspired by her second daughter's birth.

Above: "Let Them Be All" by Kyle Carey, a singer/songwriter inspired by both the American and Gaelic folk traditions. It comes from her fine second album, North Star. Carey's third album, The Art of Forgetting, is just about to be released.

Below: "At The Purchaser's Option" by Rhiannon Giddens, the brilliant young singer/songwriter/fiddler/banjo player from North Carolina who was awarded a MacArthur "genius grant" last year. (And well deserved too.) The song comes from her new album Freedom Highway (2017).

Above: Tish Hinojosa's now-classic song about migrants on the American/Mexican border, "Donde Voy (Where I Go)." She's accompanied by Mavin Dykhus in this performance, which was filmed on tour in Germany.

Below: "Going Home" performed by singer/songwriter/banjo player Abigail Washburn with . The song is from their terrific new album, Echo in the Valley (2017).

Below, to end with: "True Freedom" by Native American musician and activist Pura F��, of the Tuscarora Nation. This lovely performance was filmed two years ago at The Alhambra in Paris.

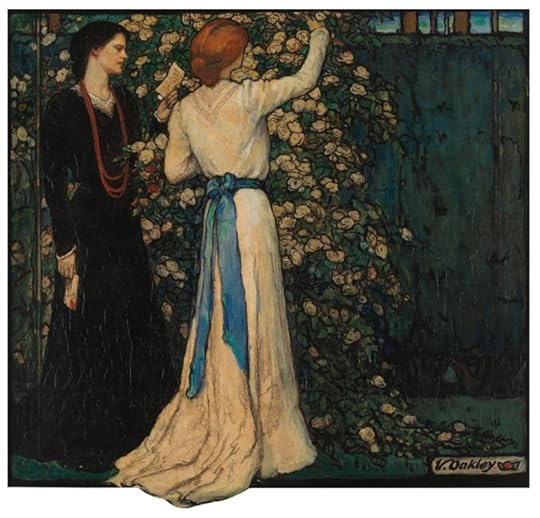

The art today is by American painter, illustrator, muralist and stained glass designer Violet Oakley (1874-1961). Oakley was one of The Red Rose Girls: three women artists who lived and worked communally at the Red Rose Inn near Philadelphia in the early 20th century. (The others were Jessie Willcox Smith and Elizabeth Shippen Green.) Read "The Exceptional Life & Polictical Art of Violet Oakey" by Carrie Rickey if you'd like to know more about Oakley, and Alice A. Carter's book wonderful book, The Red Rose Girls.

January 20, 2018

Women's March 2018

Sending love, solidarity, and flowers (in suffragette white) to everyone who is participating in the Women's March in the United States (today), the United Kingdom (tomorrow), or wherever else in the world you are gathering. I'm grateful for you all.

In 1922, writer & activist Winifred Holtby wrote in a letter to The Yorkshire Post:

"I am a feminist because I dislike everything that feminism implies. I desire an end to the whole business, the demands for equality, the suggestion of sex warfare, the very name feminist. I want to be about the work in which my real interests lie, the writing of novels and so forth. But while the inequality exists, while injustice is done and opportunity denied to the great majority of women, I shall have to be a feminist. And I shan't be happy till I get ... a society in which there is no respect of persons, either male or female, but a supreme regard for the importance of the human being. And when that dream is a reality, I will say farewell to feminism, as to any disbanded but victorious army, with honour for its heroes, gratitude for its sacrifice, and profound relief that the hour for its necessity has passed."

Like Holtby, I would prefer to focus on "the writing novels and so forth," but the work of social change is far from done. I am proud to call myself a feminist, today and every day.

The white roses were given to me by my British mother-in-law on the day of the American election in 2016. She knew how much it meant to me to vote for a woman candidate, and how devastated by the outcome I was. The picture on the wall is by our friend and neighbor Alan Lee: the cover image for JRR Tolkien's posthumous book The Children of H��rin. Howard posed for the central character in the picture some years ago, and we treasure it.

January 5, 2018

The world is a proliferation

It's taken me a long while to be receptive to the work of Scottish novelist and playwright Ali Smith, almost as if I had to learn how to read her -- but Smith's Autumn is the book that taught me how to do so, and now I'm hooked on them all. (I blush to think that I felt the same about Virginia Woolf when I was young. Thank heavens that changed.)

Another favorite writer, Olivia Laing (author of To the River, The Lonely City, etc.), noted this in a profile for The Guardian:

"I���ve known Smith since I was 17 (her partner, the artist and film-maker Sarah Wood, is my cousin). In the 1990s we used to write each other letters. Recently I unearthed a blurry photograph she sent me 20 years ago of a cat���s tail dangling over a sofa. 'I have a long-term plan to write a novella for each season,' she���d written on the back. 'It seems to me the seasons are so gifted to us that it���s a kind of duty, a very nice one.'

"Though she jokes now that she sounds like Katherine Mansfield pretending to be charming, this talk of gifts and duties gets to something essential about Smith. She believes in unselfish communal values such as altruism and generosity and has an infectious faith in hospitality, be it to new ideas or strangers. In addition to writing eight novels and five collections of short stories, she has fought against the mass closure of public libraries ('libraries matter because we���re living in an age of disinformation') and the proposed scrapping of the Human Rights Act; is a patron of the charity Refugee Tales and a staunch advocate for young writers and writers who have fallen out of fashion. She���s not, in short, an artist who seeks to wall herself off from the world."

Even in the Mythic Fiction field, where we render life through myth and metaphor, many of us are likewise determined not to wall ourselves off from the world but to use our art to guide each other through the dark. Smith shows how to do so without slipping from storytelling into didactism.

From Autumn, Smith's poetic and powerful "post-Brexit" novel, published last year:

"Her mother sits down on the churned-up ground near the fence. I���m tired, she says. It���s only two miles, Elisabeth says. That���s not what I mean, she says. I���m tired of the news. I���m tired of the way it makes things spectacular that aren���t, and deals so simplistically with what���s truly appalling. I���m tired of the vitriol. I���m tired of the anger. I���m tired of the meanness. I���m tired of the selfishness. I���m tired of how we���re doing nothing to stop it. I���m tired of how we���re encouraging it. I���m tired of the violence there is and I���m tired of the violence that���s on its way, that���s coming, that hasn���t happened yet. I���m tired of liars. I���m tired of sanctified liars. I���m tired of how those liars have let this happen. I���m tired of having to wonder whether they did it out of stupidity or did it on purpose. I���m tired of lying governments. I���m tired of people not caring whether they���re being lied to any more. I���m tired of being made to feel this fearful. I���m tired of animosity. I���m tired of pusillanimosity. I don���t think that���s actually a word, Elisabeth says. I���m tired of not knowing the right words, her mother says. "

Lord, yes.

From Public Library & Other Stories:

"Elsewhere there are no mobile phones. Elsewhere sleep is deep and the mornings are wonderful. Elsewhere art is endless, exhibitions are free and galleries are open twenty-four hours a day. Elsewhere alcohol is a joke that everybody finds funny. Elsewhere everybody is as welcoming as they���d be if you���d come home after a very long time away and they���d really missed you. Elsewhere nobody stops you in the street and says, are you a Catholic or a Protestant, and when you say neither, I���m a Muslim, then says yeah but are you a Catholic Muslim or a Protestant Muslim? Elsewhere there are no religions. Elsewhere there are no borders. Elsewhere nobody is a refugee or an asylum seeker whose worth can be decided about by a government. Elsewhere nobody is something to be decided about by anybody. Elsewhere there are no preconceptions. Elsewhere all wrongs are righted. Elsewhere the supermarkets don���t own us. Elsewhere we use our hands for cups and the rivers are clean and drinkable. Elsewhere the words of the politicians are nourishing to the heart. Elsewhere charlatans are known for their wisdom. Elsewhere history has been kind. Elsewhere nobody would ever say the words bring back the death penalty. Elsewhere the graves of the dead are empty and their spirits fly above the cities in instinctual, shapeshifting formations that astound the eye. Elsewhere poems cancel imprisonment. Elsewhere we do time differently. Every time I travel, I head for it. Every time I come home, I look for it."

And so do I.

From Girl Meets Boy: The Myth of Iphis:

"And it was always the stories that needed the telling that gave us the rope we could cross any river with. They balanced us high above any crevasse. They made us be natural acrobats. They made us brave. They met us well. They changed us. It was in their nature to."

From Autumn:

"It's a question of how we regard our situations, how we look and see where we are, and how we choose, if we can, when we are seeing undeceivedly, not to despair and, at the same time, how best to act. Hope is exactly that, that's all it is, a mater of how we deal with the negative acts towards human beings by other human beings in the world, remembering that they and we are all human, that nothing human is alien to us, the foul and the fair, and that most important of all we're here for a mere blink of the eyes, that's all."

From Autumn:

"There's always, there'll always be, more story. That's what story is."

And from a fine interview with Smith in 2014 by Alex Clark:

"Smith describes herself as 'a really uncool, geeky enthusiast.' Was she aware of the power of books from a young age? 'Oh, always!" she laughs. 'I was profoundly changed by Charlotte's Web. When you fall in love with a book something especially interesting and exciting is happening because of the way language works on us as human beings. And I love language. And I also love butterflies, and cloud-shapes, and types of train. What can I say? The world is a proliferation."

Words: Follow the links above to read the full articles by Olivia Laing and Alex Clark. The poem in the picture captions is from the Food/Land issue of of the Canadian magazine Guts (Fall, 2015); all rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: Dartmoor ponies on Chagford Commons on a winter's day.

January 4, 2018

Vade mecum

Robert Macfarlane's "Word(s) of the Day" is one of the delights of Twitter (a medium that swings from soul-enriching to soul-crushing, depending on how you curate your Twitter feed). Yesterday Robert offered vade mecum: a Latin term, he explained, meaning: "literally 'go with me'; figuratively a book that one keeps by one���s side or close to hand -- so that it may be readily consulted for guidance or inspiration. A lodestone text to which one returns. What���s your vade mecum?"

Despite my fierce passion for books, his question is one I find difficult to answer. There are just so many books that I return to again and again -- from fantasy to realist fiction, from folklore studies to nature writing, from artist and writer biographies to poetry. To chose a single lodestone text is impossible for me: influence and inspiration is everywhere. As soon as I come up with single title, a dozen others crowd close behind it, and then a dozen more.

I like these words by British novelist Ali Smith, who was posed a similar question in an interview last year:

"What book has most inspired me? The question just made my brain explode into fizzing little pieces. I can't choose one. There are so many. I think I've been by everything I've ever read one way or another, and I don't mean just books, I mean things on hoardings, things on the sides of pencils, things that catch your eye on the sides of buses, the words FRAGILE BREAK GLASS on the front of a firehose cabinet in an Italian hotel. My partner Sarah just said, stop being inspired by everything. Is this piece of newspaper really inspiring to you? Yes, I said, so don't throw it away. (She threw it away anyway, but that was inspiring too, because it inspired me to write this paragraph.) Inspiration is everywhere. It's as everday as what it means, which is literally in-breath, the act of breathing in. If we think about it like that, inspiration becomes not just natural, first nature, but how we live, how we stay alive -- a matter of heart, blood, rhythm."

Indeed.

What do you think, dear readers? Do you have a vade mecum (or two, or three), and if so, what?

Or does the question make your brain go into meltdown, as it does to mine?

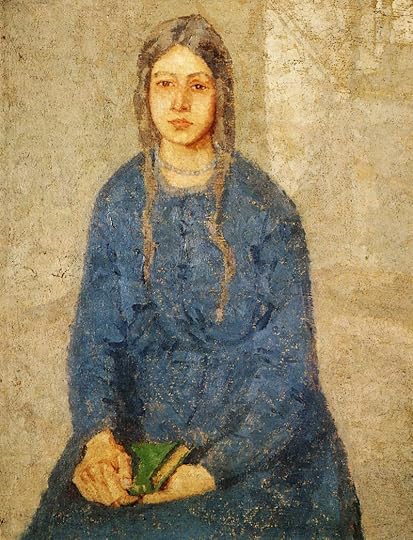

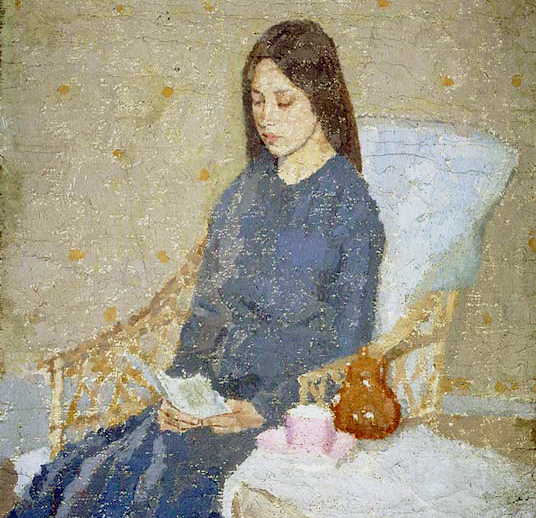

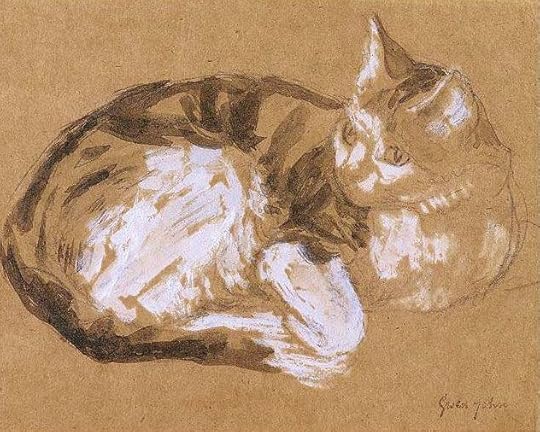

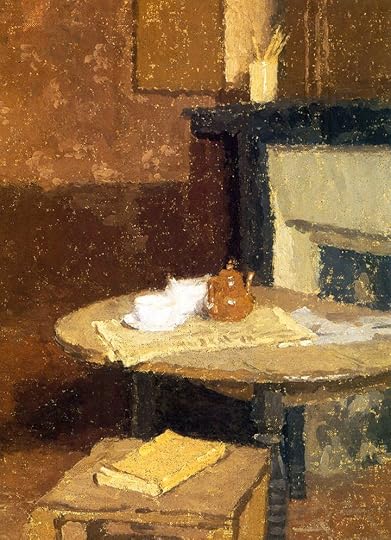

The imagery today is by the great Welsh painter Gwen John (1876-1939), who is one of my all-time favourite artists. I wrote more about Gwen back in the autumn of 2011. You can find the post here.

With thanks to the good folks at #WomensArt, who reminded me today of my love for Gwen's work. And, of course, to Robert Macfarlane, author of The Wild Places, The Lost Words, etc.

With thanks to the good folks at #WomensArt, who reminded me today of my love for Gwen's work. And, of course, to Robert Macfarlane, author of The Wild Places, The Lost Words, etc.

January 2, 2018

First day back in the studio

Over the last few days, I've been asking friends how they feel about New Year's celebrations, and from my small sampling (mostly of writers and artists) this is what I've learned:

The vast majority answered with the equivalent of a shrug: The New Year's holiday? They could take or leave it. A smaller (but emphatic) group detest it for a variety of reasons: the social pressure to be happy on New Year's eve, the guilt-tripping nature of New Year resolutions, the arbitrary designation of the year's end in the Gregorian calendar, or simply the bad timing of yet another celebration on the heels of Christmas. I found just a small minority who genuinely love New Year's Eve and Day, and I'm in the latter category. In fact, it's my favorite holiday (despite spending it in bed with flu again this year), and so I've been thinking about the reasons why -- especially since I generally mark the changing of the seasons by the pagan, not the Christian, calendar.

I grew up with the Pennsylvania Dutch traditions of my mother's large extended family: nominally Christian, but rich in folklore, folk ways, and homely forms of folk magic. One of those traditions was my mother's practice of taking down the Christmas tree on New Year's day, cleaning the house from top to bottom, and then opening the kitchen door (with a great flourish) to sweep the old year out and welcome in the new: my mother, my great-aunt Clara, and I each taking turns with the broom. Christmas was a hard time for my mother and always ended in tears, but she would rally by New Year's day, relishing the act of making order out of chaos: a woman's ritual, shared only with me and not my brothers. (Boys doing housework? Unthinkable in that time and place.)

At some point in the midst of all that cleaning, my mother and I would sit down at the kitchen table, eat the last of the kiffles (a traditional cookie made only a Christmas; it is bad luck to eat them past New Year's Day), and talk about plans for the year ahead. These were not New Year's resolutions, exactly; no lists were made, nothing was written down. It was more like a verbal conjuring, a vision of what we'd do differently and better, spoken at the right folkloric time when words held the power of an incantation: the pause between the old year and the new when anything seemed possible.

My mother was a great believer in new beginnings, in a way that was both painful and brave. We moved around a lot when I was young, in search of work for my stepfather -- whose alcoholism and violent temper ensured that employment never lasted long. In each new place my mother would mentally sweep her troubles out the kitchen door and make a brand new start: each house, each job, each new school for my brothers and me would be different, better, and we'd finally settle down. In fact, each house was worse than the last, but she'd swiftly set about transforming it, making small amounts of money go a long, long way: she'd paint the rooms (in surprising colors, dictated by the paint choices in the bargain bin), make new curtain in cheery fabrics edged with Ric Rac and Pom Pom trim, scour yard sales for lamps and dishes (constantly broken in drunken rages). For a while she'd be happy and fiercely optimistic...until the usual troubles caught up with us. There would be fights, and tears, and everything would shatter. My mother would collapse, her husband disappear to his bars. Then she'd pick herself up, we'd move again, and she'd start afresh with quiet courage.

During those years, I moved even more often than my mother did, bouncing between her, my grandparents and other relatives, with a couple of stints in foster care -- and so I needed my mother's lesson in embracing change rather more than most. Many people from peripatetic childhoods react with a deep dislike of change. My own reaction is a mix of opposites. My childhood has left me with a soul-deep need for home, place, and community -- yet I also love stepping into the unknown and using the act of re-location as a catalyst for transformation and renewal. In this I am my mother's daughter. I like transitions, beginnings, the changing of the seasons, the turning of the calendar's pages. As I wrote in a previous New Year post:

"I have a great affection for those moments in time that allow us to push the 're-set' buttons in our minds and make a fresh start: the start of a new year, the start of a new week, the start of a new morning or fresh endeavor. As L. M. Montgomery (author of Anne of Green Gables) once wrote, 'Isn't it nice to think that tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet?'

" 'Every man should be born again on the first day of January. Start with a fresh page," advised the American theologian and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher. Some people, of course, find a blank page terrifying...but that's a feeling I've never quite understood. I love the feeling of potential inherent in an untouched notebook, a fresh white canvas, even a new computer folder waiting to be filled. It's the same sense of freedom to be found at the start of a journey, when all lies ahead and limits haven't yet been reached.' "

My mother died from cancer sixteen years ago, at roughly the age that I am now, and she never managed to turn those new beginnings into the safe, stable life that she wanted. The determined optimism she practiced wasn't always entirely admirable. Optimism can also be blind or foolish, and prevent the solving of problems through the refusal to accept reality. A fresh start can only tranform a life if it is followed by the hard and clear-eyed work of making substantive change: leaving the violent husband, for example, rather than putting fresh paint on walls that will soon be bloodied once again.

There are many reasons my mother wasn't able make those harder changes -- and I'm not going to sit in judgement of her now. I'm just going to love her for who she was. Acknowledge her quiet bravery. And appreciate the gifts that she's passed on: kiffles and a broom on New Year's Day. And a love of new beginnings.

Yesterday I swept the house. Today I am the sweeping the studio. I'm thinking about what I'll do differently, and better.

The world is full of possibilities.

Pictures: The photographs today are from Queen's Wood, an ancient woodland in London's Muswell Hill: 52 acres of oak and hornbeam trees. The pictures were taken during the Christmas holiday, which we spent with our daughter in the city. I recommend "The History and Archaeology of Queen's Wood" by Michael Hacker if you'd like to know more about this beautiful place: a tranquil, magical piece of wild preserved within a bustling cityscape.

Words: The poem in the picture caption is from Tell Me by Kim Addonizio (BOA Editions, 2000); all rights reserved by the author.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers