Terri Windling's Blog, page 76

April 15, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

The world is a fractured and fractious place right now, so let's start the week with some harmony.

Above: "Green Unstopping" by The Rheingans Sisters: Anna and Rowan Rheingans, from the Peak District of Derbyshire. The song comes from their second album, Bright Field, which has just been released.

Below: "She Took a Gamble" by Hannah Read, a Scottish singer/songwriter who now lives in Brooklyn, New York. The song appears on her second album, Way Out I'll Wander (2018). The video was shot on the Island of Eigg in the Scottish Hebrides.

(Both Rowan and Hannah participated in the "Songs of Separation" project on the Island of Eigg, discussed in a previous post.)

Above: Bruce Springsteen's "I'm on Fire" performed by The Staves: sisters Jessica, Camilla and Emily Staveley-Taylor, from Hertfordshire. Their most recent album is The Way is Read (2017).

Below: "Floral Dresses" by Lucy Rose, a singer/songwriter from Warwickshire, backed up by The Staves. The song is from her third studio album, Something���s Changing (2017).

To end with:

"Horses" by Dala: Sheila Carabine and Amanda Walthe from Ontario, Canada. This song -- as perfect and poignant as a Charles de Lint story -- appears on their fourth album, Everyone is Someone (2009), and their live album, Girls from the North Country (2010).

April 12, 2018

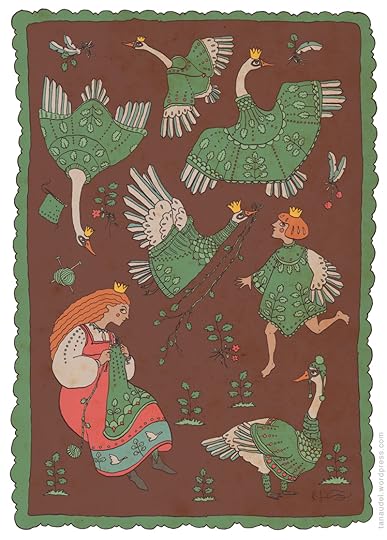

Hen Wives, Spinsters, and Lolly Willowes

In the colored fairy books of Andrew Lang (The Red Fairy Book, The Blue Fairy Book, etc.), there is a figure who has always intrigued me: the Hen Wife, related to the witch, the seer, and the herbalist, but different from them too: a distinct and potent archetype of her own, an enchanted figure beneath a humble white apron. We find her dispensing wisdom and magic in the folk tales of the British Isles and far beyond (all the way to Russia and China): a woman who is part of the community, not separate from it like the classic "witch in the woods"; a woman who is married, domesticated like her animal familiars, and yet conversant with women's mysteries, sexuality, and magic.

Writer and mythographer Sharon Blackie describes the Hen Wife like this:

"If you look up the definition of ���henwife��� in most dictionaries, you���ll find it given as something along the lines of ���woman who keeps poultry���. But that isn���t it at all: a henwife is so much more than that, as so many folk and fairytales from Ireland and Scotland show. In those tales, the henwife is often a herbalist or a healer, and is  always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ���Kate Crackernuts���, about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ���Fair, Brown and Trembling���. The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ���Kate Crackernuts���, about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ���Fair, Brown and Trembling���. The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

Colleen Szabo, writing in Cabinet des F��es, views the Hen Wife through a Jungian lens. She is, says Szabo, "a combination of the old bird goddesses and the figure we now call 'witch'; a crone or wise woman who knows of the inner life, of natural processes and developments, of all their alchemical magic. She is also a keeper of knowledge about a woman���s sexuality; the old tradition of a 'hen���s night' is currently being revived. In that tradition, the night before a wedding, older and wiser hen-wives teach the wife-to-be about sexuality, including pregnancy, all of which falls within the overall category of creative power, of course. Whatever our creative genres might be, their products can always be symbolized by the metaphor of the child, including our creative efforts to renew and transform ourselves."

My favorite depiction of the Hen Wife is in this gorgeous passage from the novel Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978):

"Laura never became as clever with the birds as Mr. Saunter. But when she had overcome her nervousness, she managed them well enough to give herself a great deal of pleasure. They nestled against her, held fast in

the crook of her arm, while her fingers probed among the soft feathers and rigid quills of their breasts. She liked to feel their acquiescence, their dependence upon her. She felt wise and potent. She remembered the henwife in fairy tales, she understood now why kings and queens resorted to the henwife in their difficulties. The henwife held their destinies in the crook of her arm, and hatched the future in her apron. She was sister to the spaewife, and close cousin to the witch, but she practiced her art under cover of henwifery; she was not, like her sister and her cousin, a professional. She lived unassumingly at the bottom of the king's garden, wearing a large white apron and very possibly her husband's cloth cap; and when she saw the king and queen coming down the gravel path she curtseyed reverentially, and pretended it was eggs they had come about. She was easier to approach than the spaewife, who sat on a creepie and stared at the smoldering peats till her eyes were red and unseeing; or

the witch, who lived alone in the wood, her cottage window all grown over with brambles. But though she kept up this pretense of homeliness she was not inferior in skill to the professionals. Even the pretence of homeliness was not quite so homely as it might seem. Laura knew that the Russian witches live in small huts mounted upon three giant hen's legs, all yellow and scaly. The legs can go; when the witch desires to move her dwelling the legs stalk through the forest, clattering against the trees, and printing long scars upon the snow.

"Following Mr. Saunter up and down between the pens, Laura almost forgot where and who she was, so completely had she merged her personality into the henwife's. She walked back along the rutted track and down the steep lane as obliviously as though she were flitting home on a broomstick."

I first discovered Sylvia Townsend Warner's fiction through Kingdoms of Elfin (a collection of the adult fairy stories as dry and fizzy as the best champagne), but Lolly Willowes, when I first read it back in my 20s, seemed altogether different. I'm embarrassed now to admit that I found the novel slight and unmemorable, almost twee, and it wasn't until a later re-reading that I finally understood it as the masterpiece it is. I had been too young for Lolly Willows the first time, and  too ignorant of the social context in which Townsend Warner was writing in the 1920s: the restricted lives of "spinisters" in Victorian and Edwardian England.

too ignorant of the social context in which Townsend Warner was writing in the 1920s: the restricted lives of "spinisters" in Victorian and Edwardian England.

"The issue that the novel tackles head-on is that of gender," explains another Townsend Warner fan, contemporary British novelist Sarah Waters: "In the 1910s and 20s British sexual mores were shaken up as never before: the war saw women taking on new jobs, gaining new responsibilities and freedom, and, though the majority of the jobs were savagely withdrawn with the return to peace, many of the liberties remained; in 1918, partly as a recognition of their contribution during the years of conflict, women were at last granted the vote. For the first decade of its life, however, the new franchise was an incomplete one, available only to women over 30 who were also householders or married to householders (which meant that single women such as Laura, middle-aged but financially dependent on male relatives, remained without it), and there was still huge pressure on women to conform to social norms.

"The recent tragic loss of so many young male lives had inflamed existing tension over the idea of the 'surplus woman' and, with postwar anxiety about British 'racial health' prompting celebrations of family life and maternity, the spinster -- a benign if dowdy figure in 19th-century culture -- was being subtly redefined as a social problem. The popularisation of Freudian ideas about sexual repression only added to her woes, pathologising elderly virgins as chronically unfulfilled. Many novelists of the period responded to this ��� some, such as Clemence Dane, with representations of emotionally vampiric single women, which reinforced the new stereotypes, but others, such as Radclyffe Hall, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain, with more sensitivity to the pressures faced by ageing, unmarried daughters, and more sympathy for them in their efforts to follow non-traditional paths. Two fascinating novels that particularly resemble Lolly Willowes, and which Townsend Warner could be said effectively to have rewritten, are W.B. Maxwell's Spinster of this Parish (1922) and F.M. Mayor's The Rector's Daughter (1924).

"Like Townsend Warner, Maxwell and Mayor chose as their subjects unmarried women of the late-Victorian age -- that is, the final generation to have assumed as a matter of course that its single daughters would remain in the family home, dutifully servicing the needs of senior relatives. Again like her, they produced novels that are intensely alive to the contrast between the unglamorous exteriors of their 'old maid' heroines and the women's actual, deeply passionate, emotional lives. But the titles of the three novels reveal a significant difference. As phrases, 'spinster of this parish' and 'the rector's daughter' testify to the ways in which women are often occluded by social and familial roles. Lolly Willowes, by contrast, is a statement of individuality. Laura's journey, too, is very different from that of Maxwell's and Mayor's heroines, the former of whom spends decades as the unacknowledged mistress of a celebrated explorer, and is finally rewarded by marriage to him, while the latter dies after a short but 'useful' life, with her passionate love for a clergyman unfulfilled.

"For the first half of Townsend Warner's novel, Laura looks set to follow their example. A tomboy in childhood, she is soon 'subdued into young-ladyhood,' and after the death of her parents she joins the London household of her unimaginative brother, Henry, where she becomes the spinster 'Aunt Lolly,' slightly pitied, slightly patronised, but 'indispensable for Christmas Eve and birthday preparations' -- an embodiment, in other words, of an old-fashioned female tradition for which her up-to-the-minute niece,

Fancy, who has driven lorries during the war, has fine, flapperish contempt. But Laura has depths unsuspected by her deeply conventional relatives, and with her move to Great Mop she grows ever more subversive. She quietly rejects her family. She refuses to be defined by her relationships with men. She breaches the social barriers between gentry and working people. And, though she enjoys being part of the Great Mop community, her intensest pleasures are solitary ones. Again looking forward to Virginia Woolf, the novel asserts the absolute necessity of 'a room of one's own', and Laura gains a clear-sighted understanding of the combined financial and cultural interests that serve to keep women in domestic, dependent roles: 'Society, the Law, the Church, the History of Europe, the Old Testament . . . the Bank of England, Prostitution, the Architect of Apsley Terrace, and half a dozen other useful props of civilisation' have robbed her of her freedom just as effectively as have her patronising London relatives. It is this analysis that informs her conversation with Satan near the end of the novel, in which she unfolds her memorable vision of women as sticks of dynamite, 'long[ing] for the concussion that may justify them.' If women, Townsend Warner implies, are denied access to power through legitimate means, they will turn instead to illegitimate methods -- in this case to Satan himself, who pays them the compliment of pursuing them and then, having bagged them, performs the even more valuable service of leaving them alone."

I highly recommend reading Water's full essay, "Sylvia Townsend Warner: the neglected writer," published by The Guardian.

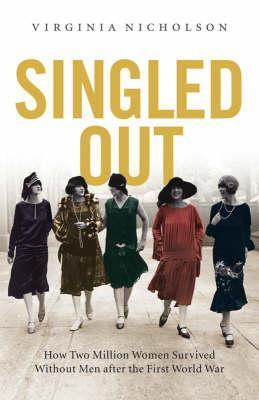

I think if I was teaching Lolly Willowes today, I would first ask students to read Singled Out by Virginia Nicholson, an absolutely engrossing book about single women in Britain between the wars, which I can't recommend highly enough. (All of Nicholson's books on social history are just terrific.)  It's also interesting to read Townsend Warner's fiction with some knowledge of her fascinating life as a feminist, leftist, and lesbian (she was in a long-term relationship with fellow writer Valentine Ackland) at a time when this was far from the norm for respectable "lady writers." She loved living in the countryside, and some of her best stories take place in rural settings -- but they are so much more than charming tales of villages and vicarages; beneath the mannered surface they contain a biting wit, deep wisdom, and sharp social critique, �� la Jane Austen. There's a good biography of Townsend Warner by Claire Harman, plus various volumes of the author's correspondence, and For Sylvia, a lovely memoir by Townsend Warner's wife (or so she'd be acknowledged today), Valentine Ackland.

It's also interesting to read Townsend Warner's fiction with some knowledge of her fascinating life as a feminist, leftist, and lesbian (she was in a long-term relationship with fellow writer Valentine Ackland) at a time when this was far from the norm for respectable "lady writers." She loved living in the countryside, and some of her best stories take place in rural settings -- but they are so much more than charming tales of villages and vicarages; beneath the mannered surface they contain a biting wit, deep wisdom, and sharp social critique, �� la Jane Austen. There's a good biography of Townsend Warner by Claire Harman, plus various volumes of the author's correspondence, and For Sylvia, a lovely memoir by Townsend Warner's wife (or so she'd be acknowledged today), Valentine Ackland.

And this brings us back to the Hen Wife -- that figure of magic who dwells comfortably among us, not off by the crossroads or in the dark of the woods; who is married, not solitary; who is equally at home with the wild and domestic, with the animal and human worlds. She is, I believe, among us still: dispensing her wisdom and exercising her power in kitchens and farmyards (and the urban equivalent) to this day -- anywhere that women gather, talk among themselves, and pass knowledge down to the next generations.

And Hen Husbands? What is their role in folklore, fairy tales, and daily life? I confess I do not know. Those are Men's Mysteries, hidden and ancient, and not for the likes of me to speak of....

Words: The passage by Sharon Blackie is from "The Henwife" (The Art of Enchantment, October 2014). The passage by Colleen Szabo is from "Katie Crackernuts: The Hen-Wife and her Cauldron of Wisdom" (Cabinet des F��es, July 2011). The passage by Sylvia Townsend Warner is from her novel Lolly Willowes, first published in 1926. The passage by Sarah Waters is from "Sylvia Townsend Warner: the neglected writer" by Sarah Waters (The Guardian, March 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in February 2015.

Pictures:

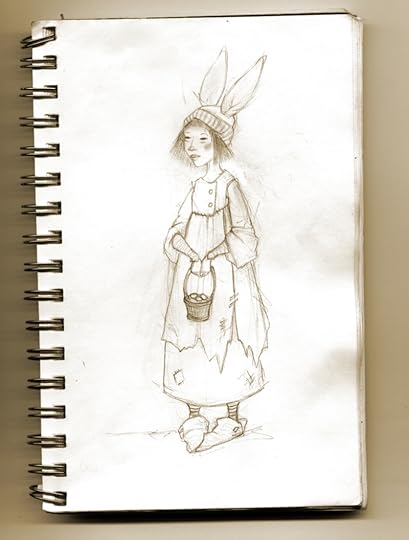

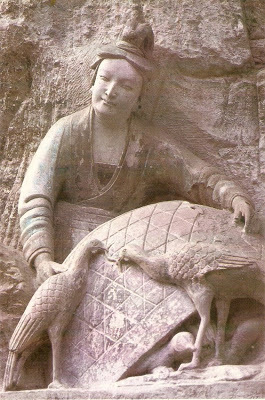

a folktale illustration by Vladislav Erko; "The Hen Wife" by Helen G. Stevenson (circa 1930s); a Danzu carving of a Chinese hen wife; "The Hen Wife" by Charles Sims (1872-1928); a nursery rhyme illustrated by Walter Crane (1845-1915); "Baba Yaga" (from Russian folklore) by Rima Staines; a Mother Goose illustration, artist unknown; a photograph of Sylvia Townsend Warner; the first edition of Lolly Willowes; a stereotypical Victorian image of a spinster by English painter Walter Dendy Sadler (1854-1923); an 18th century spinster by Thomas Cheesman (1760-1834) - reminiscent of the fact that the term was once used for all women who spin, card, and weave, rather than as a pejorative term for unmarried women; a decoration by Walter Crane (1845-1915); and "Samurai Chicken Defender" by my Chagford neighbor David Wyatt, from his "Mythic Village" series. All rights reserved by the artists or their estates.

Let's talk about genre

In "Let's Talk About Genre: Neil Gaiman and Kazuo Ishiguro in Conversation," Neil notes that when Tolkien first published The Lord of the Rings it wasn���t regarded as part of the fantasy genre:

NG: [T]he first part was reviewed in the Times by W.H. Auden. It was a novel, and that it had ogres and orcs and giant spiders and magical rings and elves was simply what happened in this novel. Back then these books tended to be produced in exactly the same way as you produced The Buried Giant, in that you���d written other things, and now you wanted to do a book in which, for the novel to work, you needed a dragon breathing magical mist over the world; you needed it to occur in a post-Arthurian world; you needed your monsters and your ogres and your pixies. There were people like Hope Mirrlees -- who wrote modernist poetry and profoundly realistic fiction and who was one of the Bloomsbury set, but produced a wonderful novel called Lud-in-the-Mist -- and Sylvia Townsend Warner, who wrote books like Kingdoms of Elfin. And these were simply accepted as part of mainstream literature.

KI: So what happened? Why have we got this kind of wall around fantasy now, and a sense of stigma about it?

NG: I think it came from the enormous ��commercial success in the Sixties, when the hippie world embraced The Lord of the Rings and it became an international publishing phenomenon. At Pan/Ballantine, the adult fantasy imprint, they basically just went through the archives of books that had been published in the previous 150, 200 years and looked for things that felt like The Lord of the Rings. And then you had people like Terry Brooks, who wrote a book called The Sword of Shannara, which was essentially a Lord of the Rings clone by somebody not nearly as good, but it sold very well. By the time fantasy had its own area in the bookshop, it was deemed inferior to mimetic, realistic fiction. I think reviewers and editors did not know how to speak fantasy; were not familiar with the language, did not recognise it. I was fascinated by the way that Terry Pratchett would, on the one hand, have people like A.S. Byatt going, 'These are real books, they���re saying important things and they are beautifully crafted,' and on the other he would still not get any real recognition. I remember Terry saying to me at some point, 'You know, you can do all you want, but you put in one fucking dragon and they call you a fantasy writer.'

Later in the conversation, Neil discusses his now-classic book Coraline to examine the ways that ideas about genre change. Since he and I grew up in the fantasy publishing world in the same generation, I remember this well:

NG: I remember as a boy reading an essay by C.S. Lewis in which he writes about the way that people use the term 'escapism' -- the way literature is looked down on when it���s being used as escapism ���--and Lewis says that this is very strange, because actually there���s only one class of people who don���t like escape, and that���s jailers: people who want to keep you where you are. I���ve never had anything against escapist literature, because I figure that escape is a good thing: going to a different place, learning things, and coming back with tools you might not have known.

I was book-reviewing a lot in the early Eighties, and it seemed for a while like all young adult books were the same book: about some kid who lived in slightly squalid circumstances, with an older sibling who was a bad example, and the protagonist would have a bad time and then run into a teacher or adult who would inspire them to get their life back on track. It was depressing. The wonderful thing about J. K. Rowling was that suddenly the idea that you can write books for kids that go off into weird and wonderful places ��� and actually make reading fun -- is one of the reasons why children���s books went from being a minor area of the bookshop to a huge force in British publishing.

When I started writing Coraline, in 1991, and showed it to my editor, he explained that what I was writing was unpublishable. He wasn���t wrong. His name was Richard Evans; he was a very smart man, with good instincts. When he explained why writing a book intended for children and adults that was functionally horror fiction for children was unpublishable, I believed him.

KI: The objection was what, exactly? That it was too scary?

NG: It was too scary, it was very obviously aimed at both children and adults, it was weird, fantastic horror fiction, and they didn���t have a way of publishing it. They knew which librarians bought what and how things got reviewed, and this was simply not something that they could have sold. It wasn���t until much later, when I was in a world in which the Lemony Snicket books had happened, and Philip Pullman and Rowling were being read, and the idea of crossover books aimed at both children and adults existed, that it was published.

KI: Perhaps things that deviated from realism were treated with great suspicion. But Coraline seems to be self-evidently a book that confronts all kinds of very real things. It���s about a child learning to make distinctions between certain kinds of parental love, to distinguish between a love that is based on somebody���s need and fulfilling somebody���s need, and what is actually genuine parental love, which may not at first glance look particularly demonstrative. I don���t see how anybody can mistake it for a kind of escapism: you���re not just taking children on some sort of strange, enjoyable ride.

NG: I think the rules are crumbling and I think the barriers are breaking. I love the idea also that sometimes, if you���re actually going to write realistic fiction, you���re going to have to include fantasy.

I recommend reading the whole conversation, which you'll find here.

Words: The passages above are from "Let's Talk About Genre: Neil Gaiman and Kazuo Ishiguro in Conversation" (The New Statesman, 4 June, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The illustrations are by Henry Justic Ford (1860-1941) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961). The photographs were taken on Nattadon Hill on a rare bright day. (We've had a very wet transition from winter to spring this year.)

April 11, 2018

Fantasy is reality

From Joanna Russ, (1937-2011), the ground-breaking author of The Female Man, How to Suppress Women's Writing, etc.:

"Fantasy is reality. Aristotle says that music is the most realistic of the arts because it represents the movements of the soul directly. Surely the mode of fantasy (which includes many genres and effects) is the only way in which some realities can be treated.

"I grew up in United States in the 1950s, in a world in which fantasy was supposed to be the opposite of reality. 'Rational,' 'mature' people were concerned only with a narrowly defined 'reality' and only the 'immature' or the 'neurotic' (all-purpose put-downs) had any truck with fantasy, which was then considered to be wishful thinking, escapism, and other bad things, attractive only to the weak and damaged. Only Communists, feminists, homosexuals and other deviants were unsatisfied with Things As They Were at the time and Heaven help you if you were one of those.

"I took to fantasy like a duckling to water. Unfortunately for me, there was nobody around then to tell me that fantasy was the most realistic of arts, expressing as it does the contents of the human soul directly.

"The impulse behind fantasy I find to be dissatisfaction with literary realism. Realism leaves out so much. Any consensual reality (though wider even than realism) nonetheless leaves out a great deal also. Certainly one solution to the difficulty of treating experience that is not dealt with in the literary tradition, or even in consensual reality itself, is to 'skew' the reality of a piece of fiction, that is, to employ fantasy.

"Sometimes authors can't face the full reality of what they feel or know and can therefore express that reality only through hints and guesses. Fantasies often fit this pattern, for example, Edith Wharton's fine ghost story, 'Afterwards.' Wharton can't afford to investigate too explicitely the assumptions and values of the society which provided her with money and position; so although the story 'knows' in a sense that the artistic culture of the wealthy depends on devastatingly brutal commecial practices, none of this can be as explicit as, say, Sylvia Townsend Warner's wonderful historical novel, Summer Will Show, in which the mid-19th century heroine ends by reading the Communist Manifesto.

"But there are other stories, quite as 'Gothic' in method and tone, which do not fit this pattern. Authors may know what their experience is and yet be unable to name it, not because it is unconscious or unfaceable, but because it is not majority experience. Shirley Jackson strikes me as a writer who does both: for example, clearly portraying Eleanor (in The Haunting of Hill House) as an abused child long before the phrase itself was invented, occasionally using material she doesn't really seem to have understood; and sometimes dislocating reality because conventional forms simply will not express the kind of experience she knows exists.

"After all, reality is -- collectively speaking -- a social invention and is not itself real. Individually, it is as much something human beings do as it is something refractory that is prior to us and outside us. "

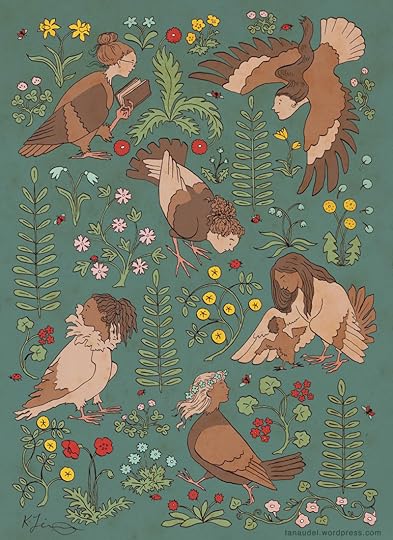

About the artist:

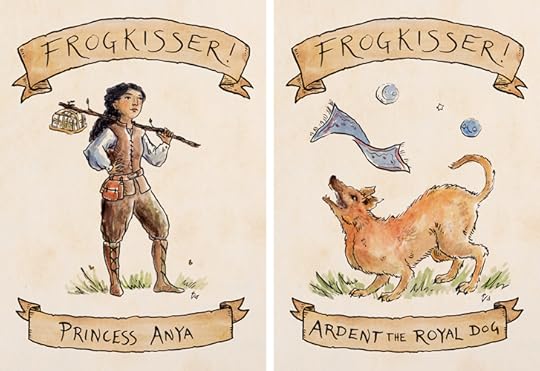

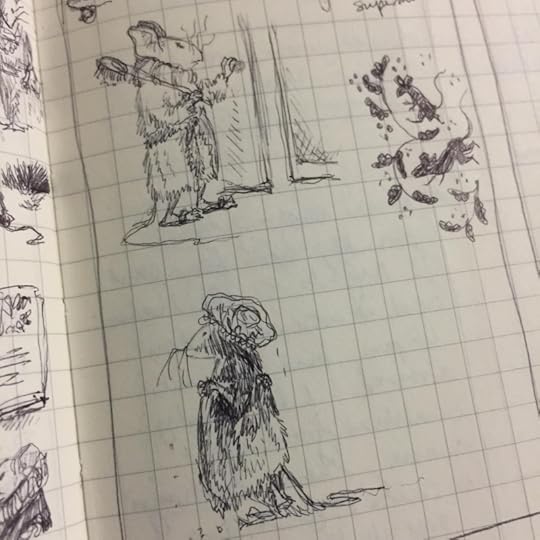

Today's imagery is from one of my favorite artists: Kathleen Jennings, an illustrator and fiction writer based in Brisbane, Australia. Raised on a cattle station in Western Queensland, she studied English literature, German, and Law at the University of Queensland, then practiced law before making the plunge into art-making full time.

She has illustrated numerous books for publishers in the U.S. and Australia -- including The River Bank, Kij Johnson's wonderful sequel to The Wind in the Willows, and The Bitterwood Bible by Angela Slatter -- and has been short-listed for the World Fantasy Award three times. She is currently on the short-list for the 2018 Hugo Award. As a writer, Kathleen won the 2015 Ditmar Award for "The Hedge of Yellow Roses" (in Hear Me Roar, Ticonderoga Press). Her most recent story is "The Heart of Owl Abbas," debuting today on Tor.com.

"I've always liked fairytales," she says, "Growing up in the country, surrounded by trees, fairly isolated and with rather primitive technology at the house, the stories seemed to seep into reality more than they might have otherwise. Fairytales are also a wonderful vocabulary (almost an alphabet) of storytelling among people who know them. You can use fairytale elements to build entirely new stories; images that work as independent pictures and narratives for viewers and readers who are new to them. But once that audience becomes aware of the depth of history and the ongoing conversation that is happening through all those layers of tellings and retellings and reimaginings, there is a splendid depth and resonance you can access."

Please visit Kathleen's delightful website and blog to see more of her work. She also has an active Patreon page full of treasures, and her enchanting designs can be purchased here.

Above: pages from one of Katheleen's sketchbooks, drawn during her first journey to Chagford. Yes, that's our Tilly on the bottom right.

The passage by Joanna Russ is from The Penguin Book of Fantasy by Women, edited by A. Susan Williams & Richard Glyn Jones (Viking, 1995). All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and the Russ estate.

April 10, 2018

Myth & Moor update

My apologies that there's been no post today. Typepad (this blog's platform) was down for most of the day, and now they've chased the gremlins out and brought us all back online again, it's late in the day and I'm about to leave the studio.

The hound and I will be back tomorrow, with new bones and new stories.

April 9, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm going to start the week with music by some of the young musicians now coming up in the British folk scene. When I despair of the world, I look at this new generation, in all areas of art and activism, and it gives me hope. But we need to support them.

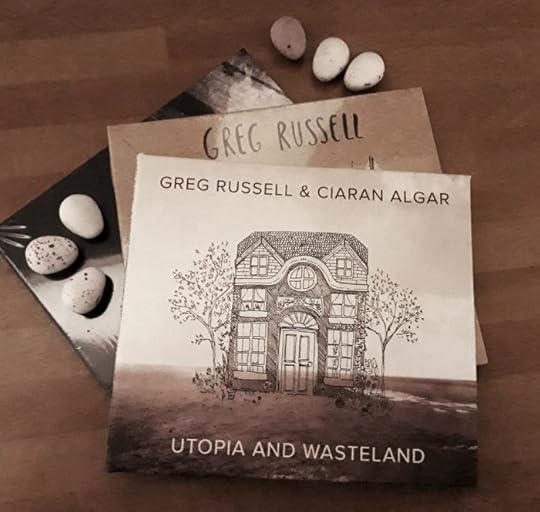

Above: "Lock Keeper" (written by Canadian folk legend Stan Rogers), performed by Greg Russell & Ciaran Algar -- whose fourth album, Utopia and Wasteland, has just been released. It's beautifully crafted, with a socio-political edge (in the great Ewan MacColl tradition), full of stories both old and new, and just incredibly good.

Below: "Seven Hills" (written by Greg Russell), which is also from the new album.

Above: "Silent Majority" (written by the late Scottish musician Lionel McClelland), performed by Russell & Algar in 2017. The song, which can be found on their terrific third album of the same name (2016), is all too relevant today -- particularly here in Britain, where the protest movement is still small (compared to America) despite the toxic, 1%-driven politics upending our lives.

Below: "Road to Dorchester" (written by Mick Ryan & Graham Moore), performed by Russell in 2017. The song appears on his fine solo album, Inclined to be Red (2017).

Above: a beautiful cover of "Delicate" (by Damien Rice), performed by Russell & Algar with singer/songwriter Luke Jackson in 2016. (Yes, it's all young men in this post. I've been sharing plenty of women's music in the last few months, including here and here, so today it's the lad's turn.)

Below: Luke Jackson gives a lovely stripped-down folk performance of "Free Falling" (by Tom Petty), backed up by Andy Sharps and Elliott Norris, filmed at Light Tones Studios a few weeks ago. Jackson also has a new album out: Solo - Duo - Trio, recorded live in Canterbury. With influences ranging from folk to the blues, it's well worth seeking out. That voice! It melts my bones.

To end with, above:

"We've Got Stories" (2015), written and performed by Luke Jackson and Emrys Plant to raise funds for the Wise Words project, which aims to engage young people with spoken word, "inspiring wonder & curiosity through unexpected encounters with poetry and storytelling." I love this so very much.

April 6, 2018

Prowling Plymbridge Woods

"To be in touch with wilderness," writes storyteller & mythographer Martin Shaw, "is to have stepped past the proud cattle of the field and wandered far from the Inn's fire. To have sensed something sublime in the life/death/life movement of the seasons, to know that contained in you is the knowledge to pull the sword from the stone and to live well in fierce woods in deep winter.

"Wilderness is a form of sophistication, because it carries within it true knowledge of our place in the world. It doesn't exclude civilization but prowls through it, knowing when to attend to the needs of the committee and when to drink from a moonlit lake. It will wear a suit and tie when it has to, but refuses to trim its talons or whiskers. Its sensing nature is not afraid of emotion: the old stories are are full of grief forests and triumphant returns, banquets and bridges of thorns. Myth tells us that the full gamut of feeling is to be experienced.

"Wilderness is the capacity to go into joy, sorrow, and anger fully and stay there for as long as needed, regardless of what anyone else thinks. Sometimes, as Lorca says, it means 'get down on all fours for twenty centuries and eat the grasses of the cemetaries.' Wilderness carries sobriety as well as exuberance, and has allowed loss to mark its face."

I'm reminded of these words from the American writer, naturalist, and activist Terry Tempest Williams:

"So much more than ever before, I feel both the joy of wilderness and the absolute pain in terms of what we are losing. And I think we're afraid of inhabiting, of staying in, this landscape of grief. Yet if we don't acknowledge the losses, then I feel we won't be able to step forward with compassionate intelligence to make the changes necessary to maintain wildness on the planet."

And the wild within ourselves.

Words: The long passage above is from A Branch from the Lightening Tree: Ecstatic Myth & the Grace in Wilderness by Martin Shaw (White Cloud Press, 2011). The quote first appeared on Myth & Moor in a post from 2012, with different photographs. The gorgeous poem in the picture captions first appeared in the Comments below the same post, and is copyright �� 2012 by the author, Jane Yolen. The Terry Tempest Williams quote is from a radio interview reprinted in A Voice in the Wilderness, edited by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Plymbridge Woods, on the other side of Dartmoor, between winter and spring.

April 5, 2018

The Wild Time of the Sickbed

As those who also have medical issues can concur, it's not just the large, dramatic things (surgery, chemo, and the like) that disrupt our schedules and overturn our plans, it's often the small things too: the side-effects of a medication, for example; or the body's shock after an invasive test; or a simple virus making the rounds, knocking others out for a couple of days while knocking us out for a couple of months. Illness takes time, and time for artists is a crucial resource. Writing, editing, or illustrating a book, for example, takes hours and hours of focused attention; and whenever we are knocked from the ladder of health, it feels like our time has been stolen.

Yet the loss is not really of time itself, but of one particular form of it: the "productive" time prized in our commerical culture, which priviliges results and finished products over process. "Time is money," as the old saying goes, and a sick person's time is not worth a bad penny. Yet paradoxically, when we're in poor health we are often rich in time, but in the wrong kind of time: the "unproductive" time of the sickbed. After a lifetime lived in the liminal space between disability and good health, I have come to believe "unproductive" time has its place and its value as well.

The business world operates on a linear concept time, structured in regular working hours, measured by schedules, spreadsheets, targets; products made, marketed, and sold. Art-making is not a linear process, but those of us who work in the arts professions do our damn best to pretend that it is: writing books to deadline, making film or theatre to schedule, etc., while walking a precarious tightrope stretched between the muse and the marketplace. It's not an easy balance, but we do it. We live in a market culture, after all, and daily life jogs along by its rules. But illness cares nothing for markets; we do not heal in a linear fashion; and the common symptoms of failing health (the brain-fog, fatigue, and fevers of a body engaged with repairing itself) are at odds with the fast and furious pace of an industrialized, digitalized world.

Time, during an illness, slows and meanders: we sleep and wake, sink and rise, drift through the days absorbed in the mysteries of the body -- its fluids and fevers, its terrors and comforts, its cycles of pain and merciful release -- while our colleagues rush past in a bright busy world that seems far removed and unreal.

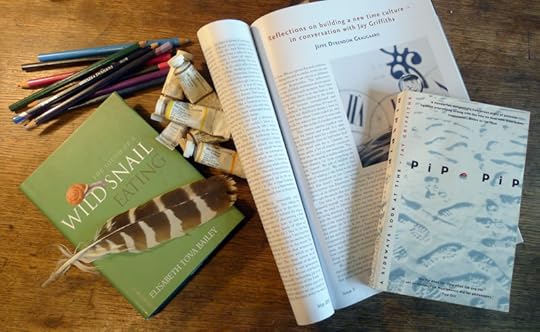

In her poetic memoir of illness, The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, Elizabeth Tova Bailey reflects on the time she spent bedridden with a semi-paralysing auto-immune disease:

"The mountain of things I felt I needed to do reached the moon, yet there was little I could do about anything and time continued to drag me along its path. We are all hostages of time. We each have the same number of minutes and hours to live within a day, yet to me it didn't feel equally doled out. My illness brought me such an abundance of time that time was nearly all I had. My friends had so little time that I often wished I could give them what I could not use. It was perplexing how in losing health I had gained something so coveted but to so little purpose."

I sympathize with Bailey's despair about the "mountain of things" she suddenly could not do, (I've often felt the same), but I resist defining the slowed-down time of the sickbed as time that has no use. There are many modes of experiencing the world, and linear time is just one of them. During illness, I enter a different mode: slower, stranger, cyclical, tidal. Attuned to the immediate environment. I see it as a form of Wild Time, a term coin by cultural historian Jay Griffiths (in her excellent book on time, Pip Pip) -- defined as time that's not been dictated by modern industrial cultural norms; time rooted in the body, the land, the ebb and flow of sea and psyche.

It is always hard to remember the exact qualities of time experienced in the sickbed when we're back in the flow of the linear world; it blurs around the edges, bright and elusive as a fever dream. What I recall best about the strange Otherworld I enter whenever my body fails is how the world shrinks to the size of my bedroom, to the dimensions of a bed littered with books, and to the view out the bedroom window of garden, hill, and woodland's edge. Unable to summon the focused attention required to write, paint, or simply communicate, I surrender to those things that illness allows and facilitates: Reading, deeply and widely. Watching the natural world through window glass. Thinking the kind of thoughts that rise, for me, only in stillness and isolation.

Illness prevents me from being active. From climbing the hill up to my studio and re-engaging with the work I've left undone. But the art that I make in "productive" time is informed by the things I feel (and watch, hear, read, reflect on) during the slow, strange hours of fever and pain. Both aspects of life -- the busy studio, the quiet sickbed -- combine to make me the artist that I am.

Writing in EarthLines magazine in 2013, Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard described a conversation with musician and philosopher Morten Svenstrup about time in relation to nature and art -- reflecting on the way that time slows down when we are fully engaged in listening to music, looking at a painting, reading a book. (Or, I'd add, communing with the body in the slow, heightened time of illness.)

"Around the time this conversation took off, Morten was writing his thesis Time, Art, and Society, in which he explores the insight that when we engage with an artwork, we pay attention in a way we don't always do with other objects. The composition of an art piece, its inherent timing, cannot be forced to fit whatever our personal sense of time may be. Being a cellist, he was very aware that if we want to really engage with music, we have to surrender our immediate sense of time and listen. The question arose: what happens if we take the kind of attention we bring to bear on a painting, a symphony, or a poem into our everyday surroundings and listen to the inherent time of our neighbourhood, a nearby woodland, or our own bodies?

"Doing this, we encounter an astonishing diversity of timescales which make a mockery of the idea that there is such a thing as a singular, universal, abstract Time. The present is made up of a multiplicity of lifetimes, and getting past our personal view and tuning into what can best be described as a symphonic view of time, we immediately acquire the sense of the richness of life. By sidestepping our notion of time as something outside ourselves and independent of us, we see that everything has its own time, an Eigenzeit. This can work as an antidote to the speed that marks a society driven by principles of efficiency and growth. It is a practice which begins with noticing the world around us, paying attention and becoming present -- but which leads to a deeper understanding and connection with the places we inhabit."

Graugaard notes that an unrushed, mindful experience of time is valuable in a digital age which constantly fractures our powers of attention and concentration:

"Wresting our attention from the flurry of information that is hurtled at us through fibre-optic communication and turning it toward the depth of time is not just about engaging new ways of seeing and honing the lifeskills we need to live fully in the context of a digitalized world. It is also a way of finding joy in the places we live in, whether they are urban or rural. Surrendering and accepting what is, and figuring out what we want to hold onto and what we can let go of. Without attention we are lost. Whatever distracts attention kills our potential to be free.

"This is why resisting the progressive notion of time as linear, singular, and above all placeless is profoundly political. It is about power. Tuning into the timescapes of the other allows us to dissolve the separation that modern life requires from us. That is what is meant by the beautiful metaphor of 'thinking like a mountain.' By thinking like a mountain, we open the possibility of becoming other."

There are many ways we can pull ourselves from the frantic pace of the mechanized world and into periods of soul-enriching (perhaps even soul-saving) Wild Time. We can take breaks from the Internet, for example; or immerse ourselves in nature; or cultivate "deep attention" by making art and engaging with art. Although it's not a method most of us would choose, illness also allows us to surrender to time in a slower, wilder way, thereby fostering a deeper, richer connection to the physical world we live in.

Don't get me wrong, I prefer good health. I prefer to be energetic and active. But during those times when I'm back in bed again, too weak, too tired, too pain-raddled to keep up with the friends and colleagues racing ahead on time's straight track, I am learning to accept that mine's a slower and more meandering trail. But it has its value. It has its use. It will get me where I want to go.

About the art:

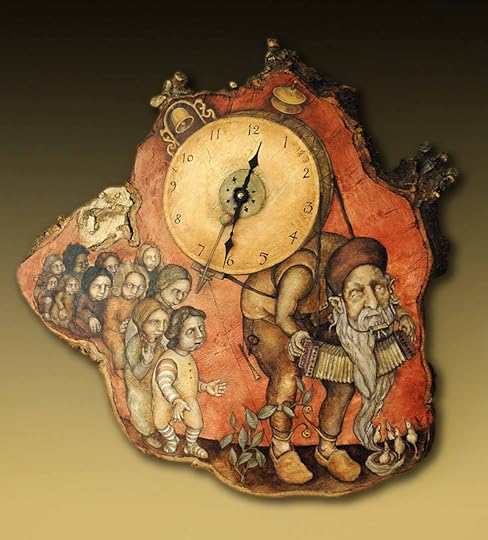

The wonderful painted clocks in this post are by my friend and Dartmoor neighbour Rima Staines, a multi-discplinary artist who uses paint, wood, word, music, animation, clock-making, puppetry and story to "build a gate through the hedge that grows along the boundary between this world and that." Born in London to a family of artists, Rima has always been stubborn, she says, about living the things that make her heart sing.

With her partner Tom Hirons, Rima also runs the Hedgespoken folk arts project. For part of the year, they travel the lanes and byways of Britain in a glorious old truck converted into an off-grid venue for storytelling, folk theatre, and puppetry. In the winter months, they return to us on Dartmoor and focus on writing, painting, and running Hedgespoken Press.

Rima���s inspirations include the world and language of folk tales, folk music, folk art of Old Europe and beyond, peasant and nomadic living, wilderness, plant-lore, magics of every feather, and the beauty to be found in otherness. To see more of her extraordinary work, visit her website: Paintings in a Minor Key, her blog: The Hermitage, and seek out her book, Tatterdemalion, co-created with Sylvia V. Linsteadt.

The passages quoted above above are from The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elizabeth Tova Bailey (Algonquin Books, 2010), and Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard's introduction to an interview with Jay Griffiths (EarthLines magazine, 2013). I highly recommend Jay Griffith's book Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time (Flamingo, 1999). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

April 4, 2018

Morning has broken

On Easter morning, 2018:

The ancient church at the heart of our village hosts an annual Easter Sunrise Service -- this year to be held on Nattadon Hill, which rises behind our house. I happened to wake very early that morning, so while the rest of the family slept I dressed in my warmest jumper and skirt, laced on my studiest walking boots, whistled for Tilly, and headed out in the cold and dark. We climbed through the oaks of Nattadon Woods and onto the open slope of the hill, the rain-rutted pathway grown visible now in the indigo light of dawn. Tilly raced ahead while I straggled behind, stopping often to catch my breath. During better times, the hound and I climb Nattadon almost every day, bounding up and down like mountain goats -- but health problems over the last several weeks have kept me on lower, easier trails. I was sorry to see how much strength I had lost as I wound my way slowly upward.

At last we reached the top of the hill. A number of people were gathered there, sharing tea and coffee and hot-cross buns, while a small fire blazed and the sun slowly rose behind clouds laying thick on the moor. It touched me to receive a warm welcome, despite not being Christian myself. I thought about all the centuries in which a pagan woman, like me, would have much to fear from the Christian church -- and so, as the Easter Service began and I silently added my own form of prayer, I felt a bone deep gratitude for this moment of inter-faith fellowship. A long time coming (historically speaking), hard won and precious. May it always be so.

The hymn chosen for the service was one I love: "Morning Is Broken" by Eleanor Farjeon. Yes, the same Eleanor Farjeon who wrote The Glass Slipper and other classics of children's fiction.

I first knew the song through Cat Stevens' version when I was a kid in the '70s, and it has personal significance. There were nights back then when I could not sleep at home due to the violence in our house, so I'd sleep instead somewhere outdoors (if the weather was warm enough), or in the family car (if it was cold). I've always been an early riser, so many a morning as the sky lightened I'd sing "Morning Has Broken" to cheer myself up. Back then, I could not have imagined I'd also sing it one day in the Devon hills, with my neighbors around me, my good dog beside me, my husband and daughter fast asleep in our warm little house below....

Yes, reader, I cried. I admit it.

Morning had broken. And we headed home.

March 30, 2018

Myth & Moor update

My apologies for the lack of posts lately. I'm continuing to have health issues, and despite having excellent medical support, it's simply not clear what precisely is going on. Living with long-term health conditions can be like this, I'm afraid (as many of you reading this know from personal experience): both western science and alternative therapies are a huge blessing for us all, but they're not infallible. Sometimes the ups-and-downs of health stubbornly resists exact diagnosis, and the healing process is a great Mystery. I'm still having medical tests of various kinds, so perhaps the Mystery will be solved...or perhaps not and I'll simply find my way back to health without any clear answers, as sometimes happens.

I seem to be doing a bit better this week. I managed to get out of the house for two events (an anti-Brexit rally last Saturday, where a friend of ours was speaking; and for a class last night), so that's progress. But strength and energy vary from day to day; I never quite know what to expect. I'm hoping to be back the studio, and thus to Myth & Moor, after the long Easter weekend. Fingers crossed.

Deep apologies to everyone I owe email to (and there are a lot of you). My mailbox is so backed up right now that it's quite daunting, but I'll make my way through it, I promise.

Have a lovely weekend, everyone. Though the weather is dreary and cold right now (when is spring going to finally arrive?), we're looking forward to a nice few days at Bumblehill. Our daughter is down from London, planning to cook a goodly holiday feast with her dad. (They are both wonderful cooks.) And Tilly is delighted to have her pack all under the same roof again. Me, I'm simply delighted to be out of bed. I want to keep it that way.

Happy Easter/Passover/pagan spring festivities...or whatever else you might be celebrating this weekend.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers