Terri Windling's Blog, page 78

February 20, 2018

Mastering the craft

From The Getaway Car: A Practical Memoir About Writing and Life by Ann Patchett:

"Why is it we understand that playing the cello will require work but we relegate writing to the magic of inspiration? Chances are, any child who stays with an instrument for more than two weeks has some adult who is making her practice, and any child who sticks with it longer than that does so because she understands that practice makes her play better and there is a deep, soul-satisfying pleasure in improvement. If a person of any age picked up the cello for the first time and said, 'I'll be playing in Carnegie hall next month!' you would pity her delusion, but beginning writers all over the country polish up their best efforts and send them off to The New Yorker. Perhaps you're thinking here that playing an instrument is not an art in itself but an interpretation of the composer's art, but I stand by my metaphor. The art of writing comes way down the line, as does the art of interpreting Bach. Art stands on the shoulders of craft, which means to get to the art, you must master the craft.

"If you want to write, practice writing. Practice it for hours a day, not to come up with a story you can publish but because you long to write well, because there is something you alone can say. Write the story, learn from it, put it away, write another story. Think of a sink pipe filled with sticky sediment: The only way to get the clean water is to force a small ocean through the tap. Most of us are full up with bad stories, boring stories, self-indulgent stories, searing works of unendurable melodrama. We must get all of them out of our system in order to find the good stories that may or may not exist in the fresh water underneath. Does this sound like a lot of work without any guarantee of success? Well yes, but it also calls into question our definition of success. Playing the cello, we're more likely to realize that the pleasure is the practice, the ability to create this beautiful sound -- not to do it as well as Yo-Yo Ma, but still, to touch the hem of the gown that is art itself.

"[My writing teacher] Allan Gurganus taught me how to love the practice, and how to write in a quantity that would allow me to figure out for myself what I was actually good at. I got better at closing the gap between my hand and my head by clocking in the hours, stacking up the pages. Somewhere in all my years of practice, I don't know where exactly, I arrived at the art. I never learned how to take the beautiful thing in my imagination and put it on paper without feeling I killed it along the way. I did, however, learn how to weather the death, and I learned how to forgive myself for it.

"Forgiveness. The ability to forgive oneself. Stop here for a few breaths and think about this, because it is the key to making art and very possibly the key to finding any semblance of happiness in life. Every time I have set out to translate the book (or story, or hopelessly long essay) that exists in such brilliant detail on the big screen of my limbic system onto a piece of paper (which, let's face it, was once a towering tree crowned with leaves and a home to birds), I grieve for my own lack of intelligence. Every. Single. Time.

"Were I smarter, more gifted, I could pin down a closer facsimile of the wonders I see. I believe that, more than anything else, this grief of constantly having to face down our own inadequacies is what keeps people from being writers. Forgiveness, therefore, is the key. I can't write the book I want to write, but I can and will write the book I am capable of writing. Again and again throughout the course of my life I will forgive myself."

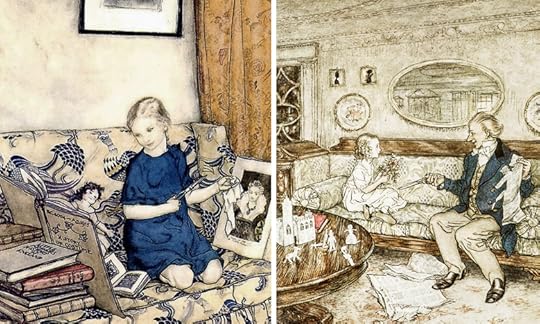

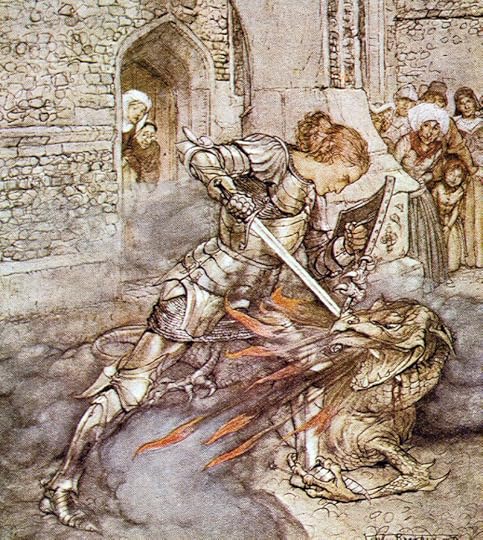

Pictures: The paintings above are by the great English book illustrator Arthur Rackham (1937-1969).

Words: The passage above is from "The Getaway Car" by Ann Patchett, published as a Kindle ebook (2011), and in her essay collection This is the Story of a Happy Marriage (Harpers, 2013), which I recommend. A portion of the text above was quoted on Myth & Moor in 2013 -- along with the poem in picture captions (which is one of mine).

February 19, 2018

The Gentle Art of Tramping

Robert Macfarlane wandered all across the British Isles before writing such fine books as Holloway, The Old Ways, and The Wild Places; and in this passage from the latter, he pays tribute to a kindred spirit, the Scottish writer Stephen Graham:

"Graham, who died in 1975 at the age of ninety, was one of the most famous walkers of his age. He walked across America once, Russia twice and Britain several times, and his 1923 book, The Gentle Art of Tramping, was a hymn to the wilderness of the British Isles. 'One is inclined,' wrote Graham, 'to think of England as a network of motor roads interspersed with public-houses, placarded by petrol advertisements, and broken by smoky industrial towns.' What he tried to prove with The Gentle Art, however, was that wildness was still ubiquitous.

"Graham devoted his life to escaping what he called 'the curbed ways and the tarred roads,' and he did so by walking, exploring, swimming, climbing, sleeping out, trespassing, and 'vagabonding' -- his verb -- round the world. He came at landscape diagonally, always trying to find new ways to move through them.

" 'Tramping is straying from the obvious,' he wrote, 'even the crookedest road is sometimes too straight.' In Britain and Ireland, 'straying from the obvious' brought him into contact with landscapes that were, as he put it, 'unnamed -- wild, woody, marshy.' In The Gentle Art, he described how he drew up a 'fairy-tale' map of the glades, fields and forests he reached: its networld of little-known wild places.

'There was an Edwardian innocence about Graham -- an innocence, not a blitheness -- which appealed deeply to me. Anyone who could sincerely observe that 'There are thrills unspeakable in Rutland, more perhaps than on the road to Khiva' was, in my opinion, to be cherished.

"Graham was also one one among a line of pedestrians who saw that wandering and wondering have long gone together; that their kinship as activities extended beyond their half-rhyme. And his book was a hymn to the subversive power of pedestrianism: its ability to make a stale world seem fresh, surprising and wondrous again, to discover astonishment on the terrain of the familiar."

'The adventure," Graham insisted, "is the not getting there, it is the on-the-way. It is not the expected; it is the surprise; not the fulfillment of prophecy but the providence of something better than prophesied. You are not choosing what you shall see in the world, but are giving the world an even chance to see you."

In her beautiful book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit looks at the history of walking through the lens of philosophy, sociology, environmental science, politics, literature and other arts:

"Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors," she observes, "disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it."

When I look at the way that Tilly takes in the world, "inside" and "outside" are alike to her, with only the annoyance of human doors between them. Nattadon Hill is home to Tilly . . . and I mean all of the hill, from top to bottom: its Commons, its woods, its tumbling streams, the brown bracken slopes, the green farmers' fields, and our warm little house on the woodland's edge. It's all home to her, both the land that is "ours" and the larger landscape that is not.

And perhaps I'm not so different from Tilly. The whole hill has become my home ground too. The concept of "home" is complex for me (being the woman that I am, with the history that I have), but the wind and rain and snow of the hill is paring that concept down to essentials:

Home is a house that I share with my loved ones. It's a landscape walked with a good black dog. It's a hill that knows my particular footsteps, and a wood where the trees all know my name. It's as simple and as solid as the earth below...but also fragile, ephemeral, therefore all the more precious. Like life itself.

Words: The passages above are from The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane (Granta, 2008); Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit (Penguin, 2001); all rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in the autumn of 2013.

Pictures: Tilly at the bottom gate to Nattadon Hill.

February 18, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, music from the members of Salt House, a Scottish folk trio consisting of Ewan MacPherson (from Shooglenifty), Lauren MacColl (from the all-women fiddle group Rant), and Jenny Sturgeon (whose project Northern Flyaway, about bird music, folklore, and ecology, we discussed a few weeks ago). They've just released a beautiful new album, Undersong, which I highly recommend. The album was recorded in a Telford church (converted into an arts studio) on the remote Isle of Berneray in the Outer Hebrides.

Above: "Staring at Stars," written by Ewan MacPherson, with a video of the making of Undersong.

Below: "Charmer," written by Jenny Sturgeon, inspired by Robert Burns' "Now Westlin' Winds."

Above: "Ruisgarry," composed by Lauren MacColl, named for a crofting township on Bernaray -- performed here with Ewan MacPherson in a cottage in the Trossachs in 2015.

Below: "Turn Ye to Me," a mournful song of the sea by Highland poet John Wilson (1785-1854), with music composed by Jenny Sturgeon -- performed here by the Salt House trio for the Cabin Sessions last November.

Above: "The Selkie Song" by Jenny Sturgeon, based on Scottish selkie lore -- performed here with Jonny Hardie (from Old Blind Dogs) on the Isle of May in 2014. The song can be found on Sturgeon's second solo album, From the Skein.

Below, to end with: "Old Shoes," Sturgeon's lovely paean to walkers and wanderers -- beautifully performed by Salt House in Aberdeenshire two years ago.

Photographs: West Beach on Bernaray by Ruth Fairbrother. A seal on the nearby island of Mingulay (from The National Trust for Scotland). The causeway to Bernaray from North Uist by Nick Corbett. All rights reserved by the photographers.

February 16, 2018

Losing and finding ourselves in books

"We use the expression 'being lost in a book,' but we are really closer to a state of being found," writes Carol Shields. "Curled up with a novel about an East Indian family, for instance, we are not so much escaping our splintered and decentered world as we are enlarging our sense of self, our multiplying possibilities and expanded experiences. People are, after all, tragically limited: we can live in only so many places, work at a small number of jobs or professions; we can love only a finite number of people. Reading, and particularly the reading of fiction, allows us to be the other, to touch and taste the other, to sense the shock and satisfaction of otherness. A novel lets us be ourselves and yet enter another person's boundaried world, share in a private gaze between reader and writer. Your reading can be part of your life, and there will be times when it may be the best part....

"We need literature on the page because it allows us to experience more fully, to imagine more deeply, enabling us to live more freely. Reading, you are in touch with your best self; and I think, too, that reading shortens the distance we must travel to discover that our most private perceptions are, in fact, universally felt."

In fantasy stories especially, writes Jane Yolen, "we learn to understand the differences of others, we learn compassion for those things we cannot fathom, we learn the importance of keeping our sense of wonder. The strange worlds that exist in the pages of fantastic literature teach us a tolerance of other people and places and engender an openness toward new experience. Fantasy puts the world into perspective in a way that 'realistic' literature rarely does. It is not so much an escape from the here-and-now as an expansion of each reader's horizons. A child who can love the oddities of a fantasy book cannot possibly be xenophobic as an adult. What is a different color, a different culture, a different tongue for a child who has already mastered Elvish, respected Puddleglums, or fallen under the spell of dark-skinned Ged?"

The great James Baldwin once said: "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive."

It was the same for me.

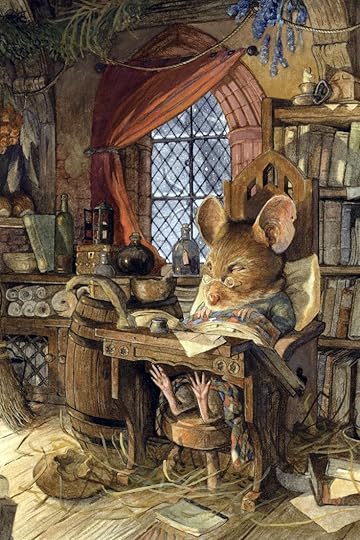

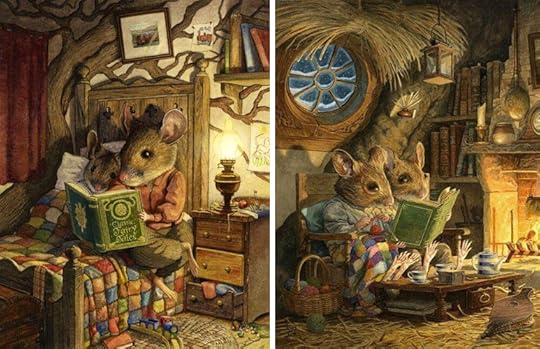

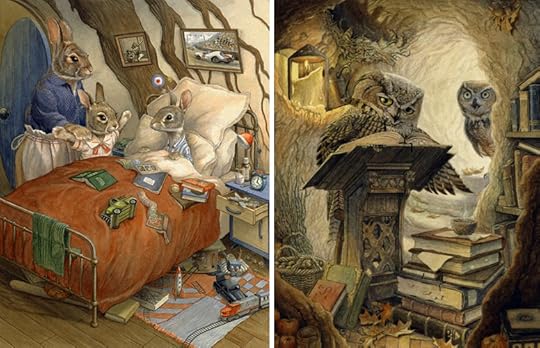

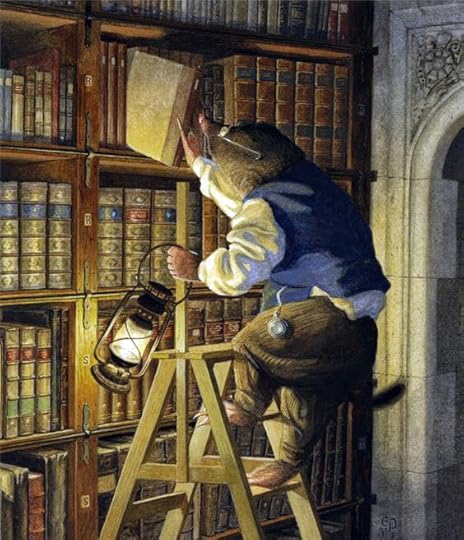

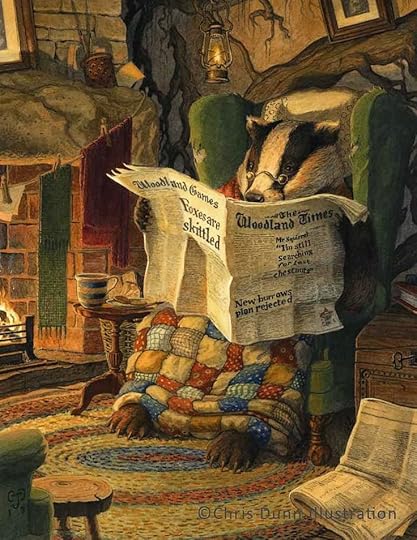

The wonderful watercolour paintings today are by Chris Dunn, a young artist based in Wiltshire whose work I completely adore. Please visit his website and blog to see more.

The Carol Shields quote is from Startle and Illuminate (Random House Canada, 2016). The Jane Yolen quote is from Touch Magic (Philomel, 1981; August House, expanded edition, 2000). I'm afraid I don't know the original source of the James Baldwin quote. All rights to the text and art above reserced by the authors and the artis

February 15, 2018

News from another country

From Startle and Illuminate, a collection of writing about writing by Canadian author Carol Shields (1935-2003):

"The resolution to become a writer formed very early in my life, but it took years for me to to discover what I would write about and who my readers would be.

"Several layers of trust were required before I began to find my direction. I had to learn to rely on my own voice, and after that to have faith in the value of my own experiences. At first this was frightening. The books I had read as a child related daring adventures, deeds of courage. The stories took place on mountaintops or in vast cities, not in the sort of quiet green suburbs where my family happened to live. It was as though there was an empty space on the bookshelf. No one seemed to talk about this void, but I knew it was there.

"Gradually I understood that the books I should write were the very books I wanted to read, the books I wasn't able to find in the library. The empty place could be closed. My small world might fill only a page at first, then several hundred pages, possibly thousands. I could make up in accuracy for what I lacked in scope, getting the details right, dividing every experience into its various shades and levels of anticipation.

"

I could write a story, for instance, about Nathanial Hawthorne School. About the school principal whose name was Miss Newbury (Miss Blueberry she was called behind her back). About the chill of fear children suffered in the schoolyard, about a suffering little boy named Walter who had an English accent, and whose mother made him wear a necktie to school. About human foolishness, and about the small rescues and acts of redemption experienced along the way. I saw that I could become a writer if I paid attention, if I was careful, if I observed the rules, and then, just as carefully, broke them.

"In the books I read -- and I find it hard to separate my life as a reader from that as a writer -- I look first for language that cannot exist without leaving its trace of deliberation. I want, too, the risky articulation of what I recognize but haven't yet articulated myself. And, finally, I hope for fresh news from another country, which satisfies by its modest, microscopic enlargement of my vision of the world. I wouldn't dream of asking for more."

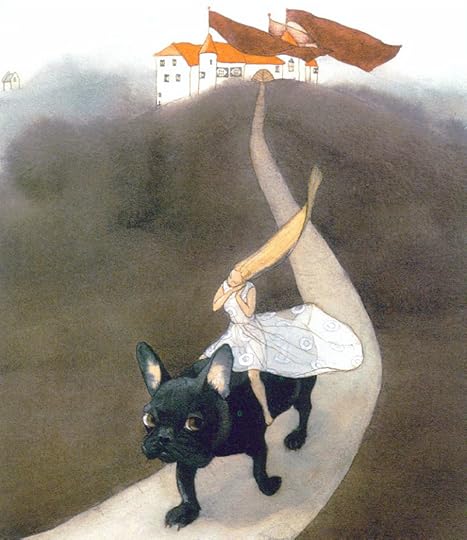

The paintings today are by the extraordinary Lisbeth Zwerger, a mulit-award-winning book illustrator based in Vienna. I highly recommend her many illustrated volumes (especially her fairy tale renditions), and the lovely collection of her work from North-South Press: The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger.

The passage above is from Startle and Illuminate: Carol Sheilds on Writing, edited by Anne and Nicholas Giardini (Random House Canada, 2016). All rights to art and text above reserved by the artist and the author's estate.

February 14, 2018

Saint Valentine's Day

by Adam Zagajewski

translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh

Without silence there would be no music.

Life paired is doubtless more difficult

than solitary existence -

just as a boat on the open sea

with outstretched sails is trickier to steer

than the same boat drowsing at a dock, but schooners

after all are meant for wind and motion,

not idleness and impassive quiet.

A conversation continued through the years includes

hours of anxiety, anger, even hatred,

but also compassion, deep feeling.

Only in marriage do love and time,

eternal enemies, join forces.

Only love and time, when reconciled,

permit us to see other beings

in their enigmatic, complex essence,

unfolding slowly and certainly, like a new settlement

in a valley, or among green hills.

It begins in one day only, from joy

and pledges, from the holy day of meeting,

which is like a moist grain;

then come the years of trial and labor,

sometimes despair, fierce revelation,

happiness and finally a great tree

with rich greenery grows over us,

casting its vast shadow. Cares vanish in it.

* An Epithalumium was composed to celebrate a wedding in ancient Greece and invoke good fortune from the gods.

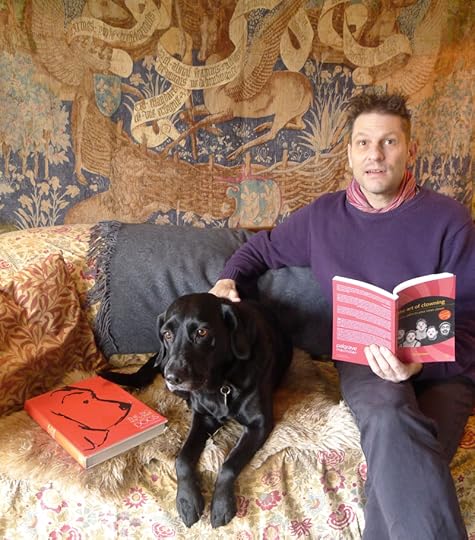

Today's post is for my valentines, one of whom is off doing theatre work in Edinburgh and London right now, while the other (furry and four-footed) pines for his return.

Happy Valentine's Day to each of you too, and to all the people, animals, trees, birds, books, fictional characters and magical places you've given your heart to.

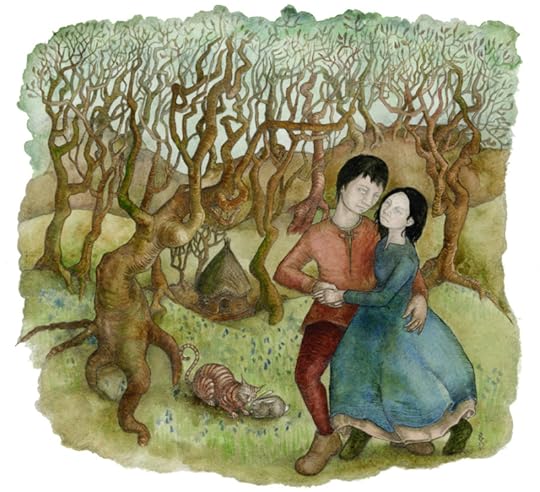

Pictures: The beautiful art above is by Rima Staines, who spreads art, music, and magic all across the UK through Hedgespoken, the house-on-wheels she shares with poet & storyteller Tom Hirons. They're out on Dartmoor for the winter months, close to their community here in Chagford, preparing for further adventures. Go here to see more of Rima's artwork.

Photographs: husband and hound, in the garden and in my studio on World Book Day.

Words: "Epithalamium" by Adam Zagajewski is from The Atlantic magazine ( June 2010). The poem excerpts in the picture captions are from: "The Country of Marriage" by Wendell Berry, from his book of the same name (Counterpoint, 1971/2013); "The moon rose over the bay, I had a lot of feelings" by Donika Kelly (The American Academy of Poets, November 2017); "Separation" by W.S. Merlin, from his collection The Second Four Books of Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 1993); and "Wedding Reading" by Ben Okri, from his collection Wild (Rider, 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. Related post: "The Narrative of Marriage."

February 13, 2018

In praise of small things

"In the Author���s mind there bubbles up every now and then the material for a story," said C.S. Lewis in an essay on writing for children. "For me it invariably begins with mental pictures. This ferment leads to nothing unless it is accompanied with the longing for a Form: verse or prose, short story, novel, play or what not. When these two things click you have the Author���s impulse complete. It is now a thing inside him pawing to get out. He longs to see that bubbling stuff pouring into that Form as the housewife longs to see the new jam pouring into the clean jam jar."

Although readers today have a marked preference for novels, there are still many of us who love short stories for their different but equal pleasures, and there are tales inside us "pawing to get out" which belong in that form and no other. "Short stories are tiny windows into other worlds and other minds and other dreams," Neil Gaiman explains. "They are journeys you can make to the far side of the universe and still be back in time for dinner."

Just because stories are shorter than novels doesn't mean they take any less skill to write. In fact, some believe they require more:

"When seriously explored, the short story seems to me the most difficult and disciplining form of prose writing extant," Truman Capote once said. "Whatever control and technique I may have I owe entirely to my training in this medium."

"In a rough way," contends Annie Proulx, "the short story writer is to the novelist as a cabinetmaker is to a house carpenter."

Jonathan Carroll describes the difference like this: "A short story is a sprint, a novel is a marathon. Sprinters have seconds to get from here to there and then they are finished. Marathoners have to carefully pace themselves so that they don't run out of energy (or in the case of the novelist, ideas) because they have so far to run. To mix the metaphor, writing a short story is like having a short intense affair, whereas writing a novel is like a long rich marriage."

"Short fiction seems more targeted -- hand grenades of ideas, if you will," Paulo Bacigalupi suggests. "When they work, they hit, they explode, and you never forget them. Long fiction feels more like atmosphere: it's a lot smokier and less defined."

Emma Donoghue notes: "The great thing about a short story is that it doesn���t have to trawl through someone���s whole life; it can come in glancingly from the side."

Haruki Murakami tells us enchantingly: "My short stories are like soft shadows I have set out in the world, faint footprints I have left. I remember exactly where I set down each and every one of them, and how I felt when I did."

But in the end it's George Saunders who describes why I love short fiction best:

"If they ever get around to building The Short Story Museum, I think they���d better carve this over the doorway: ���A short story works to remind us that if we are not sometimes baffled and amazed and undone by the world around us, rendered speechless and stunned, perhaps we are not paying close enough attention.' "

Or maybe it's just that I love small things: small ponies, small tales, small treasures of nature, small moments, small ideas, the small hound close beside me. In an interview some years ago, Sandra Cisneros reflected:

''What I didn���t know in my twenties, but am certain of now, is that there���s lots of miseria in the world, but there���s also so much humanity. All the work we do as writers is about finding balance and restoring things to balance. You need to consider the daily choices you make to create or destroy with every single act, whether it���s in words or in thoughts. The older I get, the more I'm conscious of ways very small things can make a change in the world. Tiny little things, but the world is made up of tiny matters, isn't it?''

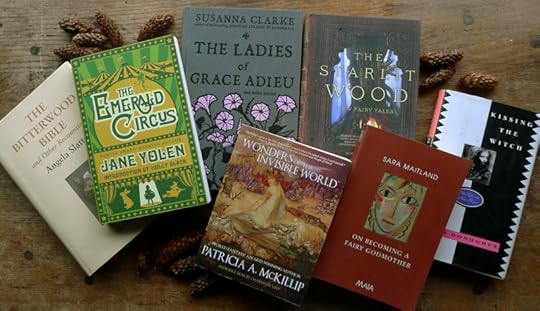

The books above (recently read or re-read) contain small gems of mythic fiction, fairy tale retellings, and fantasy literature. They are: The Bitterwood Bible by Angela Slatter; The Emerald Circus by Jane Yolen; The Ladies of Grace Adieu by Susanna Clarke; Wonders of the Invisible World by Patricia A. McKillip; The Starlit Wood: New Fairy Tales, edited by Dominik Parisien & Navah Wolfe; On Becoming a Fairy Godmother by Sara Maitland; and Kissing the Witch: Old Tales in New Skins by Emma Donoghue.

The passage by C.S. Lewis is from "On Three Ways of Writing for Children" (Of Other Worlds: Essays & Stories, Harvest Books, 2002). Related posts on the beauty of what's small: "Daily Myth" and "The Small Things."

February 12, 2018

The sea of stories

''We who make stories know that we tell lies for a living. But they are good lies that say true things, and we owe it to our readers to build them as best we can. Because somewhere out there is someone who needs that story. Someone who will grow up with a different landscape, who without that story will be a different person. And who with that story may have hope, or wisdom, or kindness, or comfort. And that is why we write.''

"This earth that we live on is full of stories in the same way that, for a fish, the ocean is full of ocean. Some people say when we are born we���re born into stories. I say we���re also born from stories."

- Ben Okri

The drawing is from "English Fairy Tales," illustrated by John Dickson Batten (1860-1932), born across the moor from here in Plymouth.

February 11, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning: Stand & Deliver!

This week's theme is highwaymen (and their bold female counterparts) in British balladry. It's a subject of particular interest to me, for I've recently learned that I'm very, very distantly related to one John Clavell (1601-1643), known in his day as the "poetical highwayman" -- a robber, a rogue, and the author of "A Recantation of an Ill Led Life." * These songs of scofflaws and ne'er-do-wells are dedicated to Ellen Kushner and the writing team of the Tremontaine series. If you're following these fabulous stories online, or have read the new anthology, Tremontaine, then you'll know why.

Above: "Shoot Them All" by Pilgrims' Way, whose new album, Stand & Deliver, is entirely devoted to highwaymen and brigands. "Shoot Them All" is their exuberant rendition of a traditional song known variously as "The Undaunted Female," "The Staffordshire Maid," and "The Serving Girl and the Robber."

Below: a terrific version of "The Newry Highwayman" by Kim Lowings and The Greenwood, from their new album, Wild & Wicked Youth. The song is also known as "The Flash Lad," "The Rambling Blade," and "Adieu, Adieu."

Above: "Alan Tyne of Harrow" by James Fagan & Nancy Kerr. The exact history of this 18th century broadside ballad is a contested one, but it's probably a variant of an older Irish song, "Valentine O'Hara."

Below: "Turpin Hero" by Jake Bugg (audio only). This too is an 18th century ballad, but based on a known historical character. As A.L. Lloyd explains: "Dick Turpin, an East End butcher���s boy, commenced his wild career by stealing cattle in West Ham and selling the beef, door to door. Pursued by the law, he took to housebreaking and highway robbery. Things became hot, he retired, got into a squabble over a gamecock, was arrested, unmasked, and hanged on April 6, 1739."

Above: "Sylvie," a song also known as "Sovay" and "The Female Highwayman." Collected in Oxfordshire in 1911 by Cecil Sharp (but certainly much older), it was popularized during the '60s folk revival by a beautiful rendition from Pentangle. The version above was recorded for a forthcoming album of ballads by Rachel McShane, with her band The Cartographers. She stitched the song together, she says, "from lyrics found in dusty old books and websites and wrote a new melody and arrangement."

Below: "The Highwayman," written by Alfred Noyes in 1906, with new music composed by Loreena McKennitt. The video contains three songs from a performance filmed in 2008 -- so skip ahead to the 3 minute mark, which is where "The Highwayman" begins.

The art in this post is from a children's book version of the Noyes ballad, illustrated by Charles Mikolaycak (1937-1993).

Some oher good songs about highwaymen: "Salisbury Plain" (Maddy Prior does a good version on Lionhearts, and Lisa Knapp on Wild and Undaunted); "Jack Hall" (Sam Carter sings this one on Live at Union Chapel); and Adam Ant's cheeky "Stand and Deliver" (from the New Romantic day of '80s rock).

*Although it's not known where the Clavell family originated (some say the Celtic region of Spain), John Clavell's branch setttled in Dorset, England, while mine lived in the French Alps, near Grenoble, before fleeing to Switzerland and the Netherlands during the Reformation. My many-times-great-grandfather, George Craft Clavel, sailed on a Dutch ship to Philadelphia as child in 1737, where he was sold to a button factory owner to help pay for the family's passage. He paid off the bond after five year's work, rejoined his family, and became a farmer and Indian trader on what was then the remote Pennsylvania frontier.

February 8, 2018

Wild Neighbors

"What would Robin Hood have made of Country Life's recent excavation into the fantasies of British 7-to-14-year-olds concerning the wild life and wild places of their native land?" asks poet and scholar Ruth Padel. "Two thirds had no idea where acorns come from, most had never heard of gamekeepers (do they  mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most believed there were elephants and lions running round the English countryside. A third did not know why you had to keep gates shut ��� was it to keep the elephants in (or was some joker taking the piss just then?), or stop cows 'sitting on cars,' upsetting the countryside's most vital beast ��� the traffic?

mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most believed there were elephants and lions running round the English countryside. A third did not know why you had to keep gates shut ��� was it to keep the elephants in (or was some joker taking the piss just then?), or stop cows 'sitting on cars,' upsetting the countryside's most vital beast ��� the traffic?

"In a closed, traditional society there is something special about animals born in the land where you, too, were born. The British used to look lazily at gardens, thickets, and moors, and know ��� without bothering to think about it ��� that foxes, hedgehogs, badgers, squirrels, and deer were out there flecking the undergrowth....

"Dangerous or vulnerable, shy or cunning, a pest or welcome visitor, our native animals are part of our romance with the secret wildness of the place we live, even if we never see much of them. We grew up with them in imagination. They were inside us, furry heroes of nursery rhymes, pictures and stories through which we learned the world. Little Grey Rabbit. The Stoats and Weasels of the Wild Wood. The Fox who Looked Out on a Moonlight Night. The Frog who would A Wooing Go. They are deep in British folk song, poetry, and popular art. 'Three Ravens Sat in an Old Oak Tree.' The holly and the ivy, the running of the deer. Landseer's 'Monarch of the Glen.'

"But that's the way it used to be. We are not a mono���traditional society any more ��� most kids' traditions center on the TV and the city street. To most children, a weasel is as unknowable as daffodils to a young Indian struggling with Wordsworth during the Raj."

How did we become so disconnected to the land we live on, and the wild neighbors we share it with? I think it's partly because we're losing the stories specific to the local landscape: the stories about this plant that grows on the hill nearby and that bird that migrates here each spring and not just the pan-cultural stories we share with everyone on the television and cinema screens. We no longer know the tales of the animals, and, increasingly, we no longer know animals themselves.

What a different attitude is conveyed by these words from a member of the Carrier Indian nation in British Columbia (quoted in Becoming Animal by David Abram):

"We know what the animals do, what are the needs of the beaver, the bear, the salmon, and other creatures, because long ago men married them and acquired this knowledge from their animal wives. Today the priests say we lie, but we know better. The white man has only been a short time in this country and knows very little about the animals; we have lived here thousands of years and were taught long ago by the animals themselves. The white man writes everything down in a book so it will not be forgotten; but our ancestors married animals, learned their ways, and passed on this knowledge from one generation to another."

The old story of a woman who marries a bear, for example, is one that used to roam widely, like the bears themselves, throughout North America. In a Nishga version recounted by Agnes Haldane of the Wolf clan of Gitkateen (in Wisdom of the Myth Tellers by Sean Kane), a tribal princess picking berries in the forest steps on a bit of bear scat and mutters angry remarks about the bears. As the women head for home, her basket breaks; repairing it, she is left behind. Two handsome men appear and tell her they've come to fetch her and lead her from the forest. Instead of leading her home, they take her to the village of the Bear People. The princess tricks the People into believing she is a woman of great power, and as a result she ends up marrying the son of the Bear Chief. She lives with him rather happily, and gives birth to two fine bear sons. But during a period of hibernation, her own brothers find her husband's cave and kill the bear in a rescue attempt. Her husband has foreseen this event. "When they skin me," he'd instructed her, "tell them to burn my bones so that I may go on to help my children. At my death they shall take human form and become skillful hunters. Now listen as I sing my dirge song. This you must remember and take to your father. My cloak he shall don as his dancing garment. His crest shall be the Prince of Bears."

The bear's sacrifice of his life for the benefit of human beings might seem suprising, but it's not an unusual theme in the indiginous tales of North America, where many story traditions say the animals were the First People, here before humans came. Sacred tales from many different Indian nations recount how Bear, or Coyote, or Eagle, or Deer first gave humans the precious, vital gift of fire; while in other tales language, hunting skills, dancing, even love-making, were first taught by animals. Though we've come to expect such respectfulness towards and from other species in American Indian lore, it can also be found in many other storytelling traditions around world -- such as in the sacred stories of the Ainu of Japan. As Gary Snyder notes (in The Practice of the Wild):

"In the Ainu world, a few human houses are in a valley by a little river. Food is often foraged in the local area, but some of the creatures come down from the inner mountains and up from the deeps of the sea. The animal or fish (or plant) that allows itself to be killed or gathered, and then enters the house to be consumed, is called a 'visitor,' marapto. Bear sends his friends the deer down to visit humans. Orca [the Killer Whale] sends his friends the salmon up the streams. When they arrive their 'armor is broken' -- they are killed -- enabling them to shake off their fur or scale coats and step out as invisible spirit beings. They are then delighted by witnessing the human entertainments -- sake and music. (They love music.) Having enjoyed their visit, they return to the deep sea or the inner mountains and report, 'We had a wonderful time with the human beings.' The others are then prompted themselves to go on visits. Thus if the humans do not neglect proper hospitality, the beings will be reborn and return over and over."

In another essay in the same volume, Snyder writes: "A young white woman asked me: 'If we have made such good use of animals, eating them, singing about them, drawing them, riding them, and dreaming about them, what do they get back from us?' An excellent question, directly on the point of etiquette and propriety, and putting it from the animals' side. The Ainu say that the deer, salmon, and bear like our music and are fascinated by our languages. So we sing to the fish or the game, speak words to them, say grace. Periodically we dance for them. A song for your supper: performance is currency in the deep world's gift economy. The other creatures probably do find us a bit frivolous: we keep changing our outfits and we eat too many different things. Nonhuman nature, I can't help feeling, is well inclined towards humanity and only wishes that modern people were more reciprocal, not so bloody."

The idea that animals love human song reminds me of this passage from Linda Hogan's gorgeous novel Power:

'[T]he panther remembers when humans were so beautiful and whole that her own people envied them and wanted to be like them. They admired the humans and the way the two-legged people stood beneath trees with leaves leaning down over them as they picked ripe fruits, how their beautiful eyes were fully open. How straight they walked! How beautiful the beads about their necks, the dresses women made in fabric that was the dark green of the trees and the light colors of flowers. How intelligent the little shell and wooden bowls they ate from, how good they were at devising ways to catch fish with simple bone and metal, at making trails through the thickets. They stood so gracefully and full of themselves, they sang so beautifully; it remembers all this, how they sang. The whole world rejoiced with their voices....

"[The panther] remembers when its own people surrounded the humans and gave them life and power, medicine to heal, to hunt, even to direct lightning and stormclouds away from their beautiful dark-eyed children....But now they have turned against her. Now that they have no need for her, Sisa and her people, the panther, are leaving. They leave in sadness and grief. Now so few of the humans have songs or presence, so many have such heaviness that they can barely walk or move, raise themselves from their beds in the morning. And Sisa believes, sees, that the world could end with their human misery."

And in Wild: An Elemental Journey (another book that I highly recommended), Jay Griffiths shares this:

"Creatures are gente, I'm told, everywhere I go in the Amazon: they are 'people like us' with customs and homes and they are accorded gentleness for being gente. You must address the world gently, I was told, even to the wind you should speak con cari��o -- with tenderness. The Harakmbut say that all animals were people m��s all�� -- long ago -- and there is therefore a profound equality between us and them; they are like distant family, and one has duties and expectations as one would with family members. People are 'familiar' with the habits and ways of animals, and this familarity is cherished. (By contrast in the West, close familiarity with animals was considered devilish: the witch and her 'familiar.')

"Animals should be treated kindly, even in hunting, for they are kin to humans. 'We owe...kindliness to other creatures: there is an intercourse and mutual obligation between them and us,' wrote Michael de Montaigne, sounding uncannily like an Amazonian Indian."

"Homo sapiens," wrote the late naturalist Ellen Meloy (in Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild) "have left themselves few scant places and scant ways to witness other species in their own world, an estangement that leaves us hungry and lonely. In this famished state, it is no wonder that when we do finally encounter wild animals, we are quite surprised by the sheer truth of them."

Louise Erdrich portrays this sense of surprise in a passage from her novel The Painted Drum:

���Coming down off the trail, I am lost in my own thoughts and unprepared when a bear chugs across the path just before it gives out on the gravel road. I am so distracted that I keep walking towards the bear. I only stop when it rears, stands on hind legs, and stares at me, sensitive nose pressed into the air, weak eyes searching. I have never been this close to a wild bear before, but I am not frightened. There is no menace in its stance; it is not even curious. The bear seems to know who or what I am. The bear is not impressed. ���

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

In From the Beast to the Blonde, Marina Warner discusses the role of "beasts" in fairy tales, and how our perceptions of these stories have changed as attitudes towards animals have changed. "Just as the rise of the teddy bear matches the decline of real bears in the wild," she notes, "so soft toys today have taken the shape of rare animal species. Some of these are not very furry in their natural state: stuffed killer whales, cheetahs, gorillas, snails, spiders and snakes -- and of course dinosaurs -- are made in the most inviting deep-pile plush. They act as a kind of totem, associating the human being with the animal's capacities and value. Anthropomorphism traduces the creatures themselves; their loveableness sentimentally exaggerated, just as formerly, belief in their viciousness crowded out empircal observation."

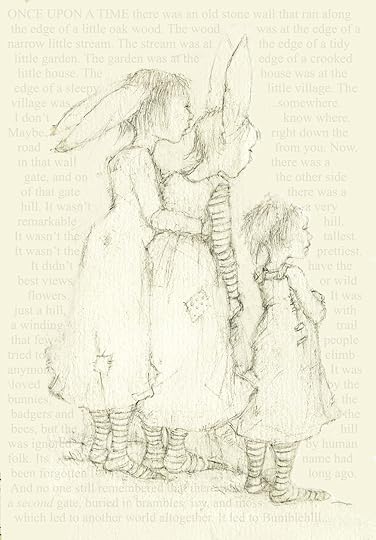

This is clearly true, and a world in which children interact only with animal-shape-objects while remaining ignorant about the creatures outside their own back door (be it country badger or urban fox) is clearly a world out of balance. And yet, for me, those soft animal toys awakened my interest in and life-long love of the wild, as did the anthropomorphised animals of tales like Peter Rabbit, Winnie the Pooh, and Wind and Willows. I'm thinking quite a lot about this these days, as I work on a book project involving bunny girls and other animal children. I want these magical beings to lead children back to nature, not to be nature's safe, cuddly substitute. Is this possible? At this point in the process, I have more questions than I have answers....

When I think back to my own childhood, what I wish is that someone had noted my passion for animals and placed a wildlife guide in my hands alongside those tales of Mole and Rat and Benjamin Bunny...or better still, led me out of doors and into the wild, and told tales of the land we then lived on. Not in place of those books, which had done their work in opening the door into wonder for me, but as the next necessary step of attaching wonder to the living world around us.

"How, then to renew our viceral experience of a world that exceeds us -- of a world that is wider than ourselves and our own creations?" asks David Abram (in Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology). "Does a revitalizing of oral [storytelling] culture mean that mean that we must renounce reading and writing? Must we empty our bookcases? Must we unplug our computers and drag them down to the dump?

"Hardly. The renewal of oral culture entails no renunciation of books, and no rejection of technology. It entails only that we leave abundant space in our days for interchange with one another and with our surroundings that is not mediated by technology: neither by television nor the cell phone, neither by the handheld computer or the GPS satellite...nor even the printed page.

"Among writers, for example, it entails a recognition (even an anticipation) that there are certain stories we may stumble against that ought not to be written down -- stories that we might instead begin to tell with our tongue in the particular topography where those stories live. Among parents, it requires that we set aside, now and then, the books that we read to our children in order to recount a vital story with the whole of our gesturing body -- or better yet, that we draw our kids out of doors in order to improvise a tale about how the nearby river feels when the fish return to its waters, or about the wild wind that's even now blustering its way through the city streets, plucking the hats off people's heads.... Among educators, it requires that we begin to rejuvenate the arts of telling, and of listening, in relation to the geographical place where our lessons actually happen."

"Can we renew in ourselves an implicit sense of the land's meaning, of its own many-voice eloquence?" David wonders. "Not without renewing the sensory craft of listening, and the sensuous art of storytelling. Can we help our students to carefully translate the quantified abstractions of science into the qualitative language of direct experience, so that those necessary insights begin to come alive in their felt encounters with cumulus clouds and bleaching corals, with owls and deformed dragonflies and the intricate tangle of mycelial mats? ...Most important, can we begin to restore the health and integrity of the local earth? Not without restorying the local earth."

"We are of the animal world," Linda Hogan reminds us (in her beautiful collection of essays, Dwelling: A Spiritual History of the Living World). "We are part of the cycles of growth and decay. Even having tried so hard to see ourselves apart, and so often without a love for even our own biology, we are in relationship with the rest of the planet, and that connectedness tells us we must reconsider the way we see ourselves and the rest of nature.

"A change is required of us, a healing of the betrayed trust between humans and earth. Caretaking is the utmost spiritual and physical responsibility of our time, and perhaps that stewardship is finally our place in the web of life, our work, our solution to the mystery of what we are."

Indeed. Part of that stewardship, surely, is caretaking our local, traditional stories as well as the land that gave birth to them. And listening for the land's new stories. Telling them. And singing, so the animals can hear us.

Pictures: The photographs above, of our four-footed and winged neighbors here in Devon, come from the Devon Wildlife Trust website. The art above: "Ratty" by my two-footed neighbor Steve Dooley (from his iillustrations Wind and the Willows); "Woman & Bear," a Victorian illustration (artist unknown); Peter Rabbit by the great Beatrix Potter; and my wee Rabbit Sisters.

Words: T

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers